Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 May 2022

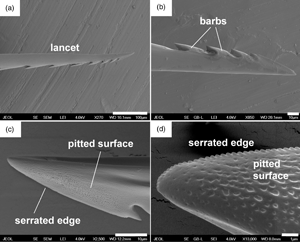

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that a micro-serrated edge on the honey bee Apis mellifera stinger tip serves as a tool for more intensive crushing of cell membranes in the victim's tissues. This could have mechanical consequences as well as initiate metabolic pathways linked to cell membrane breakdown (e.g., production of biogenic amines). Accordingly, we found that hymenopteran species that use their stingers as an offensive or defensive weapon to do as much damage to the victim's body as possible had this cuticular microstructure. In parasitic hymenopterans, on the other hand, this structure was missing, as stingers are solely used to delicately transport venom to the victim's body in order to do little mechanical harm. We also demonstrated that the stinger lancets of the honey bee A. mellifera are living organs with sensilla innervated by sensory neurons and containing other essential tissues, rather than mere cuticular structures.