Dominique-François-Jean Arago (1786–1853)

Dominique-François-Jean Arago, better known simply as François Arago, was born on February 26, 1786, in Eastagel, France. A member of a political family, Arago was provided with a classical education, studying first at Perpignan and then at the École Polytechnique in Paris. In 1809, at the age of 23, Arago became a professor of analytical geometry at the prestigious Paris school and was subsequently made director of the Paris Observatory. Interested in a variety of scientific fields, Arago's greatest contributions were in optics, astronomy, and electromagnetism. A staunch republican, Arago was also active in politics and was a distinguished statesman later in life.

During the nineteenth century, there was a great controversy regarding the nature of light. Scientists generally subscribed to one of two opinions: either light existed as particles or as a wave. Arago is best known for helping resolve this debate. Originally a supporter of the corpuscular (particle) theory, polarization research he conducted in collaboration with Augustin-Jean Fresnel changed his mind. In 1811, the pair discovered that two beams of light polarized in perpendicular directions do not interfere, eventually resulting in the development of a transverse theory of light waves.

Arago realized that if light was really a wave, its velocity should decrease when it passes into a denser substance. Therefore, he determined that the only way to truly prove that light traveled in waves was to measure its velocity in two different mediums. In 1838, he described an elaborate series of experiments, planning to use water and air as media for light beams, but his work was delayed by circumstances beyond his control. Problems with laboratory equipment, political turmoil, and failing eyesight hindered progress, but the tests were finally performed in 1850, albeit not by Arago. Armand Fizeau and Jean-Bernard-Leon Foucault carried out the research, completing Arago's work three years before his death and confirming his hypothesis.

Arago was renowned not only for his own scientific findings, but for his influence on the work of others. In the 1820s, Arago performed numerous experiments concerning the relationship between magnets and electric currents. Another French scientist, Andre Ampere, was intrigued by this research, and the pair decided to combine their efforts. Their work would eventually inspire Michael Faraday's explanation of electromagnetic induction. Arago was also instrumental in the success and funding of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre's photographic process, known as the daguerreotype, and directed studies that led to the discovery of the location of Neptune by Urbain-Jean-Joseph Le Verrier.

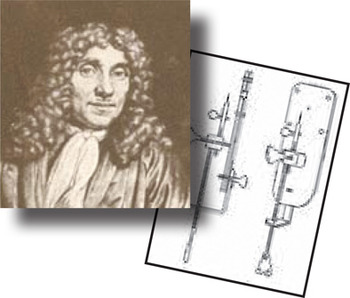

Augustin-Jean Fresnel (1788–1827)

Augustin-Jean Fresnel was a nineteenth century French physicist, most often remembered for the invention of unique compound lenses designed to produce parallel beams of light, which are still used widely in lighthouses. Born in Broglie, France, on May 10, 1788, Fresnel was the son of an architect and received a strict, religious upbringing. His parents were Jansenists, a sect of Roman Catholics that believed only a small, predestined group would receive salvation and that the multitudes could not change their fate through their actions on Earth. Fresnel's early education was provided by his parents; he was considered a slow learner, barely able to read by the age of 8. When he was 12 years old, however, Fresnel began formal studies at the Central School in Caen where he was introduced to the wonders of science and demonstrated an aptitude in mathematics.

Fresnel's academic predilections inspired him to pursue a career in engineering. He entered the Polytechnic School in Paris in 1804 and, two years later, the School of Civil Engineering. Following graduation, he worked on engineering projects for several years in a variety of French government departments but temporarily lost his post when Napoleon returned from Elba in 1815. Having already begun performing scientific work in his spare time, his new status provided Fresnel with the opportunity to increase his efforts in this arena. He soon began to focus on optics. Even when he was provided with a new engineering position in Paris after the second restoration, Fresnel continued his scientific investigations.

In the field of optics, Fresnel derived formulas to explain reflection, refraction, double refraction, and the polarization of light reflected from a transparent substance. Fresnel also developed a wave theory of diffraction. He created various devices to produce interference fringes in order to demonstrate the interference of light wavelets. Using his inventions, Fresnel was the first to prove that the wave motion of light is transverse. He accomplished this task by polarizing light beams in different planes and showing that the two beams do not exhibit interference effects.

In 1822, Fresnel invented the lens that is now used in lighthouses around the world. The Fresnel lens appears much like a giant glass beehive with a lamp in the center. The lens is composed of rings of glass prisms positioned above and below the lamp to bend and concentrate the light into a bright beam. The Fresnel lighthouse lens works so well that the light can be seen from a distance of twenty or more miles. Before Fresnel's invention, lighthouses used mirrors to reflect light from the lamp, which could be seen only for short distances and hardly at all during foggy or stormy days. Lighthouses equipped with Fresnel's lenses have helped save many ships from going aground or crashing into rocky coasts.

Although he received little public recognition for his efforts during his lifetime, Fresnel was bestowed with various honors by his fellow scientists. He was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1823 and became a member of the Royal Society of London two years later. The British organization awarded him with the prestigious Rumford Medal in what was to be the final year of his life. Having struggled with ill health since his early childhood, Fresnel died of consumption at Ville-d'Avray, France, on July 14, 1827.