Fossil arachnids—especially those dating from the Carboniferous period, 360–299 million years ago—are often found in mines or quarries within concretions of siderite (FeCO3). Most of the methods to study these fossils are either destructive or damaging to the specimens and are limited in their resolution, thereby limiting the information that can be derived from the fossil. In an elegant study, Russell Garwood, Jason Dunlop, and Mark Sutton have demonstrated that X-ray micro-tomography (XMT) can reveal hitherto unseen details in such fossils without damaging the specimens [1, Reference Garwood, Dunlop and Sutton2].

Garwood et al. examined specimens of Eophrynus prestvicii and Cryptomartus hindi that had been recovered from the Coseley quarry in Dudley, UK. These are extinct large arachnids (about 24 mm long and 15 mm wide) that are considered to be a close relative of—amongst others—modern spiders, whip spiders, and whip scorpions. Whereas they resemble spiders, they lack spinnerets (for making silk threads) and other features that define spiders. They are examples of trigonotarbids, of which about 70 species are known, many of them well-studied. They existed between 419 and 290 millions years ago. A non-destructive method of examining these arachnids in great detail would be an important contribution to the field, as it would be applicable to a large number of Carboniferous fossils.

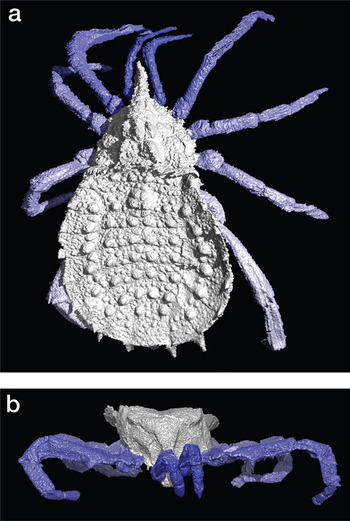

Specimens embedded within siderite were examined by XMT that provided a voxel size (resolution) of 15 to 25 microns. Three-dimensional models were created from the tomographic datasets using customized software. Many regions of the models were isolated manually, which required occasional arbitrary termination of features such as limbs, but allowed structures to be colorized and artifacts such as cracks could be removed. Through visualization of the models and iterative improvement, accurate reconstructions of the fossils were created. These could be rotated and examined at any angle at high resolution.

The general morphology of the fossils largely corresponded to earlier descriptions, but significant additional detail was evident (Figure 1). This was despite the fact that E. prestvicii has achieved an almost iconic status in the technical and popular palaeontological literature, and it has been extensively studied. XMT has allowed the robust legs and pedipalps (leg-like appendages) to be seen in full for the first time on both fossils. Other details were confirmed, including features of the carapace, such as the eyes and fangs. In E. prestvicii defensive spines were identified—in some ways, this fossil resembled certain modern harvestmen (often called “daddy-long-legs”) which are also heavily armored.

Figure 1: X-ray micro-tomographs of (a) Eophrynus prestviciiand and (b) Cryptomartus hindi. Images courtesy of Imperial College, London, and The Natural History Museum, London.

This work also demonstrated the most detailed view yet obtained of C. hindi; Garwood et al. identified growths on the inside of the creature's legs, known as coxal endites. These structures are in a similar position to those seen in distant marine relatives of the spiders, in which they are used to grind food. Comparable endites are not known from other arachnids, living or extinct. The authors were also able to infer the likely mode of life of this animal. It appeared to have a “laterigrade” stance comparable to modern crab spiders. This would suggest that these arachnids were ambush predators, grabbing prey with outstretched forelimbs.

Garwood et al. demonstrated the ability of XMT to differentiate the void left by the original organism's decay within sideritic host material and the power of computer-based 3-dimensional visualizations of the resulting datasets as a tool for morphological analysis. This new approach could well offer a new and exciting window on fossils from this fascinating period in the history of life on land.