In this Photoarticle, we survey what we will call the post-historical U.S. postage stamps of the last third of the twentieth century. We focus on stamps depicting the space race and space travel, as well as the linkage of some of those stamps to the 1992 Olympic games, to analyze the iconographic and narrative consequences of an increasing turn toward the commercialization of postal services. The stamps we consider coincide with a series of new commercial strategies on the part of the United States Postal Service (USPS) and a broad resurgence in public interest in space travel. While many critics during the 1960s considered the space race to be a distraction from more pressing political concerns—such as urban poverty or the war in Vietnam—by the 1980s and 1990s, space travel had become a less controversial endeavor (perhaps due to its large-scale defunding), and astronauts, especially the Apollo 11 astronauts, were widely lauded as heroes.Footnote 1 We have chosen this “topical” focus (as stamp collectors say) for two reasons. First, the iconography of space exploration is dominated by one specific moment, when the lunar module Eagle touched down on the moon on July 20, 1969. Despite an ongoing history of space exploration before and after 1969, the moon landing, we will argue, was treated in postal iconography as a timeless event —a climactic technological triumph that seemed to announce what Francis Fukuyama, in an influential essay, called “the end of history.”Footnote 2

Second, in 1983 the USPS began using the iconography of space exploration as a central element in advertising campaigns directed at key competitors in the expedited delivery market: Federal Express (FedEx) and United Parcel Service (UPS). Twelve years earlier, the old Post Office, a department of the federal government, had been transformed into the USPS, a government corporation, to bring businesslike efficiency to a floundering public-service agency. While the underlying mandate of the new corporation—to provide everyone in the nation, regardless of their location or ability to pay, with the same basic service—remained in place and made certain kinds of efficiencies impossible, the new USPS experimented on multiple fronts to create and advertise new, more profitable products. In this article we look particularly at one such experiment, the USPS's corporate sponsorship of the 1992 Olympics, an advertising campaign in which the space race iconography of the eagle and the moon featured prominently.

Fukuyama speculated that “the end of the Cold War” might also be “the end of history,” defined as “the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” In his estimation, none of liberalism's competitors—fascism, communism, nationalism, and other forms of identity politics—could win out in the long run over democracy and the economic prosperity that accompanied it. He predicted that once China, Russia, and other global players fell into line, all that would be left to do “after” history would be to manage the economic prosperity that would be “underwritten by the abundance of a modern free market economy.” In sum, this final stage of human history would feature “liberal democracy in the political sphere combined with easy access to VCRs and stereos.” And, Fukuyama lamented, it would be “a very sad time.” Art, philosophy, and principled political struggle would disappear, “replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems … and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.” Meaningful human action would be relegated to “the museum of human history” in this brave new world dominated instead by technology and consumer capitalism.

Fukuyama's essay on the end of history was published in the era when most of the stamps we are considering were released. The issues of central concern for us, taken altogether —the timeless portrayal of space exploration, the vision of the future as nothing more than a technologically enhanced present devoid of autonomous human actors, and the transformation of an erstwhile public service agency into a corporate sponsor hawking its wares at the Olympics—provide an almost perfect illustration of Fukuyama's vision of the end of history and the triumph of capitalism.

In the remainder of this feature, we will focus on the stamps of the period that depict achievements in space exploration and consider how they represent their moment in history as well as their relationship to consumerism. These stamps were produced by a post office that had been newly reorganized as a governmental corporation— one that was struggling to compete with private carriers in delivering outstanding service to its customers. The space stamps of interest to us might well have articulated a historical vision. But, as we will show, they did the opposite; in these stamps, the 1969 moon landing became the end of history.Footnote 3 It is thus no surprise that the postal iconography produced by this corporate entity celebrated technological and commercial success—now, as in Fukuyama's vision, deemed timeless, independent of human intervention, and the bedrock of a self-perpetuating political regime.Footnote 4

Competing with FedEx

The decade that culminated in the moon landing was one in which citizens and politicians lamented the U.S. Post Office Department (USPOD) as hopelessly incompetent to perform the work it was mandated to do.Footnote 5 For instance, in 1969, a Life magazine cover featured a letter carrier spilling a relentless torrent of letters from his mail bag with the issue headline “The U.S. Mail Mess.” Before the transformation of the USPOD into the USPS in 1971, Congress controlled the post office's budget, keeping postal rates low and wages up rather than allocating additional funding to keep postal operations on pace with a burgeoning population and new technologies. Congressional control also limited postal administrators’ ability to manage postal operations, given that priorities were set by Congress and various lobbying groups, not those with direct insight into the organization.

As a result, postal workers employed outdated technology and infrastructure designed for a population far smaller than the one they found themselves serving, even as the country's mail volume rose dramatically between 1945 and 1970. Without recourse to the tactics private industries use to cut costs and maximize profits—laying off workers, refusing certain services, and setting their own prices—and given its democratic mandate that made it impossible to reject anything deemed standard mail, the post office found itself the subject of public and political scrutiny.

In this context, the post office piloted several programs designed to appease politicians and postal users alike. Often, however, these innovations (such as an early version of facsimile mail) were not implemented—deemed too costly or incompatible with the post office's mandate to deliver letters, printed matter, and parcels. Express service, however, was an area in which the old post office had long experience, since at least the mid-nineteenth century when competition with private express companies for the carriage of intercity letters led it to inaugurate accelerated schedules on some routes. Thus it was that in 1970, even before its transformation into the USPS and before the founding of FedEx, the USPOD piloted an express delivery service (called Express Mail) “designed to be the fastest, most reliable service in the nation for the transmission of high priority business documents.” Shortly thereafter, spurred by “a jolt of competition” coming from the debut of FedEx in 1973, the USPS “refined” its system of differently priced services keyed to geographic postal zones and “expanded the system to 400 cities by October of 1974 and to 670 cities by April 1976.” Once the service became “zone-free,” the USPS issued its first Express Mail stamp in 1983.Footnote 6

Consuming the Moon

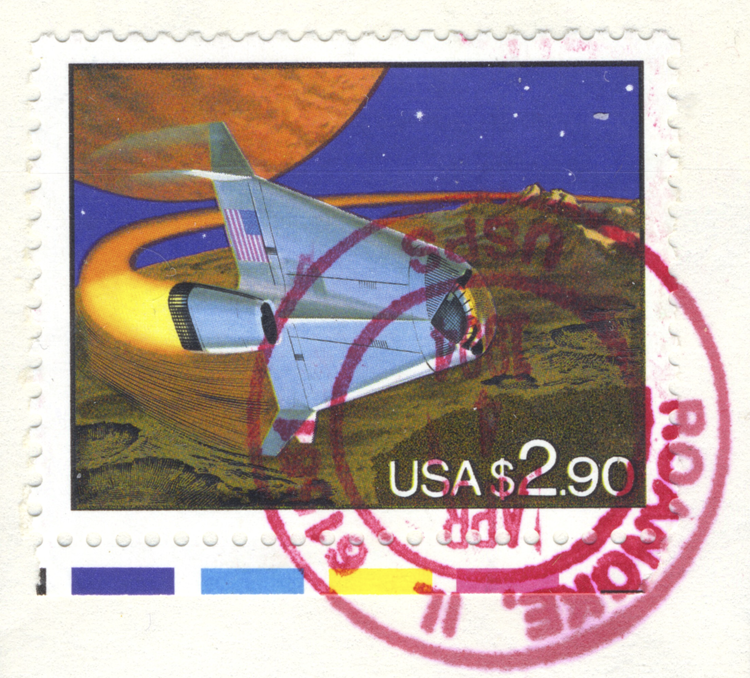

That Express Mail stamp is, technically, a definitive issue since it was intended to cover a particular service at a particular rate for as long as that rate was in effect. But, for our discussion, what is most interesting is that this first Express Mail stamp, designed explicitly for services pitched to business customers, features an image suggestive of space voyages and is thus part of a longer tradition of U.S. stamps depicting space exploration and rockets that began in 1948 with commemorative stamps for the Mount Palomar Observatory and Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. As atomic energy and the space race (and the weapons of mass destruction they made possible) became pressing matters of public and governmental concern in the 1950s, more and more stamps were issued to mark U.S. successes in rocketry and space travel—Project Mercury in 1962, Gemini 4 in 1967, Apollo 8 in 1969, and, above all, the 1969 airmail stamp celebrating the moon landing of July 20 of that year (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. 1983 Express Mail stamp, on a canceled “space-flown” envelope (source: Handler's collection).

Figure 2. Space-related stamps, 1948–1969 (source: Handler's collection).

As Kenneth Osgood, Frances Stonor Saunders, and others have argued, these stamps were part of a tradition of government propaganda that began during the Eisenhower administration. Starting in the late-1950s, government officials used state imagery to wage a psychological campaign against the Soviet Union. Directed at domestic as well as national audiences, these propagandistic materials were intended to convince citizens that the United States was not only militarily superior to the Soviet Union, but culturally superior as well.Footnote 7 In part to underscore U.S. space endeavors' differences from similar initiatives in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), many aspects of the space race and its related propaganda campaigns were controlled by private entities and nonmilitary public organizations, such as NASA. The USPS's partnership with NASA in the design and release of its first Express Mail stamp recapitulated a longstanding Cold War strategy of positing capitalist and semicapitalist practices as more transparent and efficient than government control alone, and crucial to the peaceful continuation of daily life in a free democratic society.

This first Express Mail stamp was issued in the year of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and NASA and the USPS worked together to sell their products—postage stamps and space exploration—to the public. The Express Mail Eagle nicely illustrates this cooperative marketing effort. It featured a striking portrait of the national symbol of the bald eagle superimposed on the full moon, the latter image having been taken from a 1972 NASA photograph. But the fact that the photograph was a product of publicly funded space exploration is nowhere mentioned on the stamp: neither the eagle nor the moon are identified in ways that could link the stamp to the lunar module Eagle landing on the moon nor to NASA's other efforts. Instead, this instantiation of the eagle was used to introduce the USPS's latest product, its nationwide express service designed to compete with FedEx, and the moon was chosen “to symbolize the overnight-delivery aspect of Express Mail.”Footnote 8

Moreover, the USPS marketed this stamp using a variety of gimmicks it had developed since the early 1970s when postal officials announced to collectors that it was “in the new issue business” with products “designed … to make new collectors, and to expand the market.”Footnote 9 One of these was the “space-flown cover,” an envelope (often without contents) bearing a space-related stamp that had been postmarked on dates, at times, and at sites relevant to a particular NASA flight. Almost 262,00 covers bearing the first Express Mail stamp and appropriately cancelled were flown into space and back again and then sold to collectors in a special folder for $15.35.Footnote 10

Such gimmicks gesture toward the conjunction of consumerism and the “universalization of Western liberal democracy” that for Fukuyama had defined the end of history. Unlike earlier space stamps that commemorated specific episodes of the historical space race, the first Express Mail stamp and other space stamps produced in the final decades of the century were oddly ahistorical. Indeed, they verge on the fantastic, as we shall show (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Express Mail Eagle and Olympic Rings (1991) (source: Handler's collection).

Though they adopt a different iconography, the USPS's Priority Mail stamps express a similar recasting of space exploration as commercialized and ahistorical. For example, in 1989, the USPS celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission by releasing a new Priority Mail stamp. The stamp featured a rendition of the photo of the not-yet-deceased Neil Armstrong and “Buzz” Aldrin placing the U.S. flag on the lunar surface. The depiction of a living person on U.S. currency contravened a law passed in 1866 that made such representations illegal. As we argue in our recent book, the decision to prohibit images of living persons from appearing on official state currency expressed Congress's belief that in a democratic republic—as opposed to a hereditary aristocracy—only future generations could decide who deserved to be considered a national hero and thus a figurehead for the nation.Footnote 11 But the appearance of Armstrong and Aldrin on the 1989 stamp suggested that there was no need to worry how future generations will view the present because the future will simply reproduce what has come before. Indeed, from 1969 onward, the Apollo 11 lunar landing has been repeatedly rehearsed by the USPS as its dominant space trope, in effect broadcasting Fukuyama's prediction that the future would not meaningfully differ from the present (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Moon Landing (1989) (source: Handler's collection).

Other Priority Mail stamps follow suit, depicting post–Apollo 11 space travel occurring in an ahistorical future. For example, a 1993 stamp depicts a futuristic shuttle emblazoned with a U.S. flag whizzing through space. The location is opaque—a reddish planet looms in the background as the shuttle flies above a craggy surface. The focus thus falls upon the shuttle itself and the advance of technology as of central importance (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Priority Mail Shuttle (1993) (source: Handler's collection).

This sense of an ahistorical future persists even in stamps explicitly devoted to the historical. Take, for instance, the “Space Exploration” stamps released to kick off National Stamp Collecting month in 1991, a commercial pitch aimed at stamp collectors. Each stamp represents one of the nine planets in our solar system (Pluto was considered a planet until 2006), with an additional stamp devoted to Earth's moon.Footnote 12 Alongside these planets, the stamps commemorate the unmanned NASA spacecraft that had visited each of these celestial bodies, except for Pluto. The space vehicles lack any sense of direction or momentum, or even a pursued object. Rather than directionality, we have stasis as the space vehicles float motionless in space. Moreover, these stamps are eerily devoid of human figures; they seem to celebrate a technology that is both ahistorical and autonomous.

Yet other possibilities were contemporaneously available. While technology was often a dominant theme in the marketing of the space race, both real and fantastical renditions of space exploration focused equally on the human body. Take, for instance, 1960s television series such as Star Trek and Lost in Space where the narrative tension often resolves when the human form triumphs over technology. Indeed, as the sheer number of scenes featuring a shirtless Captain Kirk indicates, Star Trek and similar shows revel in the human body, featuring human figures traipsing in alien worlds unencumbered by space suits in every single episode. Technology in this instance serves both to liberate and celebrate the human body, as Star Trek imagines a peaceful future where technology has advanced to such a degree that the human body can exist in the hostile environment of space without its visible trappings. Likewise, in the buildup to the Apollo 11 mission, the New York Times and other national news outlets frequently profiled the Apollo 11 astronauts, providing as much attention to their clothing and mannerisms as to their illustrious achievements (see Figures 6–8).Footnote 13

Figure 6. Space Exploration (1991) (source: Handler's collection).

Figure 7. Captain Kirk wrestling without his shirt on, “Charlie X” (source: Goldblatt's collection).

Figure 8. The Enterprise crew on an alien plant, “That Which Survives” (source: Goldblatt's collection).

In contrast to these fictional depictions, but like the Space Exploration set, many space stamps either trivialize the human element or render it fantastical. The trend is strikingly illustrated in three sets of 1975, 1981, and 1992. The 1975 Apollo-Soyuz issue is a two-stamp se-tenant set that narrates an event, “the first international manned space mission.”Footnote 14 One stamp depicts the U.S. and USSR's space vehicles at the moment before linkup, the other immediately after linkup has been achieved. The illustrations are striking but restrained (while the earth is luminous, space itself is dark), and no humans are depicted (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Apollo-Soyuz (1975) (source: Handler's collection).

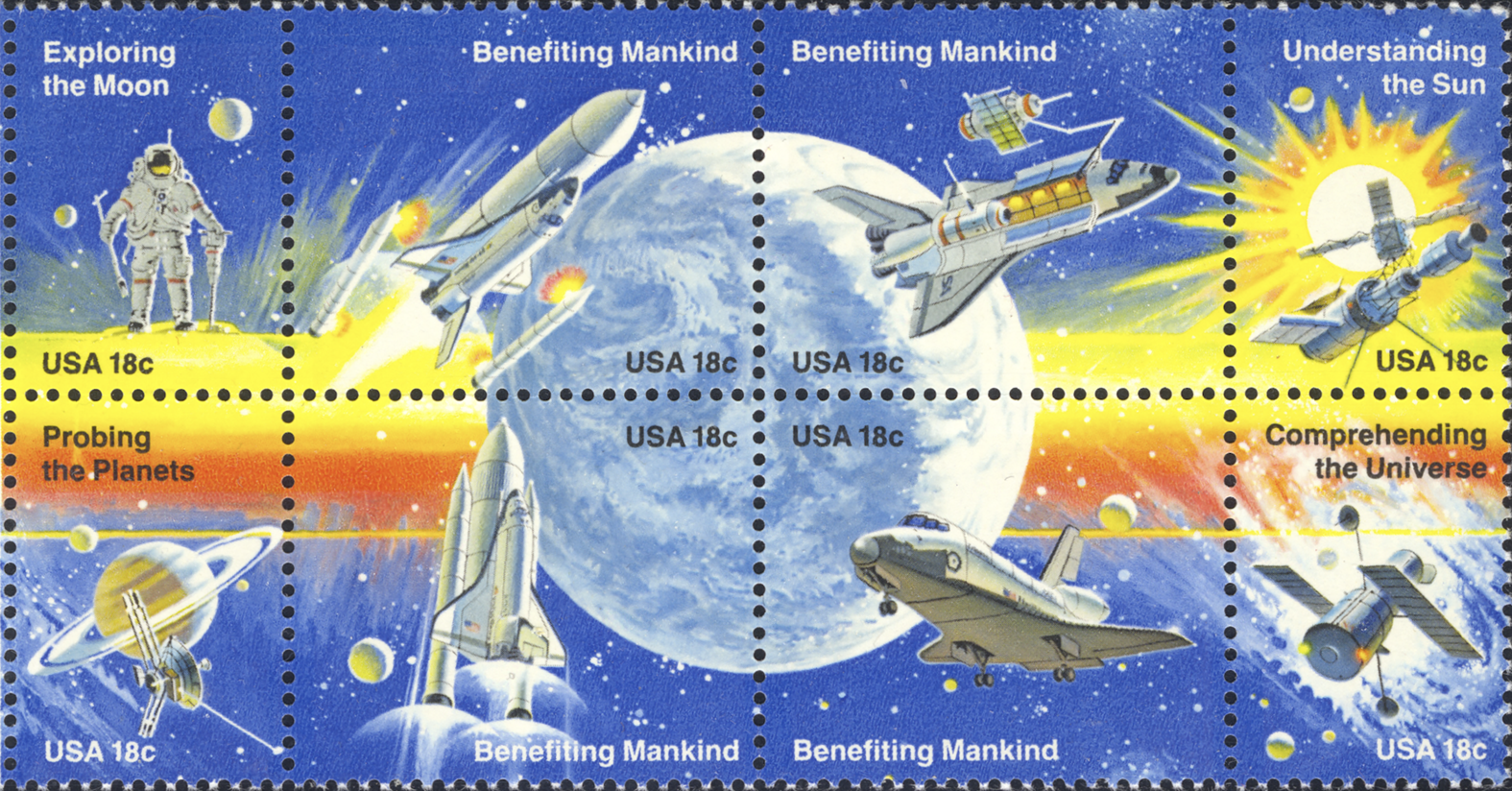

Six years later, the “Space Achievements” issue celebrated the first Space Shuttle flight from the Kennedy Space Center on April 12–14, 1981. The eight-stamp se-tenant set depicts various objects closely related to space travel: an astronaut, the Space Shuttle, a telescope, spacecraft, and Skylab. Further, each stamp includes a tagline (one sometimes repeated) to describe what the stamp depicts: “Exploring the Moon,” “Benefiting Mankind,” “Understanding the Sun,” “Comprehending the Universe,” and “Probing the Planets.” Yet despite exaggerated colors and jet streams, none of the objects or people depicted seem to move toward any object. Rather, they either float aimlessly in space or remain arrested on the lunar surface, a stasis that seems devoid of urgency or purpose. Even fantasy lacks a vision of a future that evolves significantly from the past. Likewise, the stamp's taglines fail to tell a particular story. The use of the se-tenant format in this case seems more like a commercial ploy to make the brightly colored stamps eye-catching rather than a narrative device. Add to this the lack of people (with the predictable exception of the moon walker encased in a space suit that hides his human features), and the exploration of space again comes to seem hauntingly devoted to autonomous technology—things—rather than humans (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Space Achievements (1981) (source: Handler's collection).

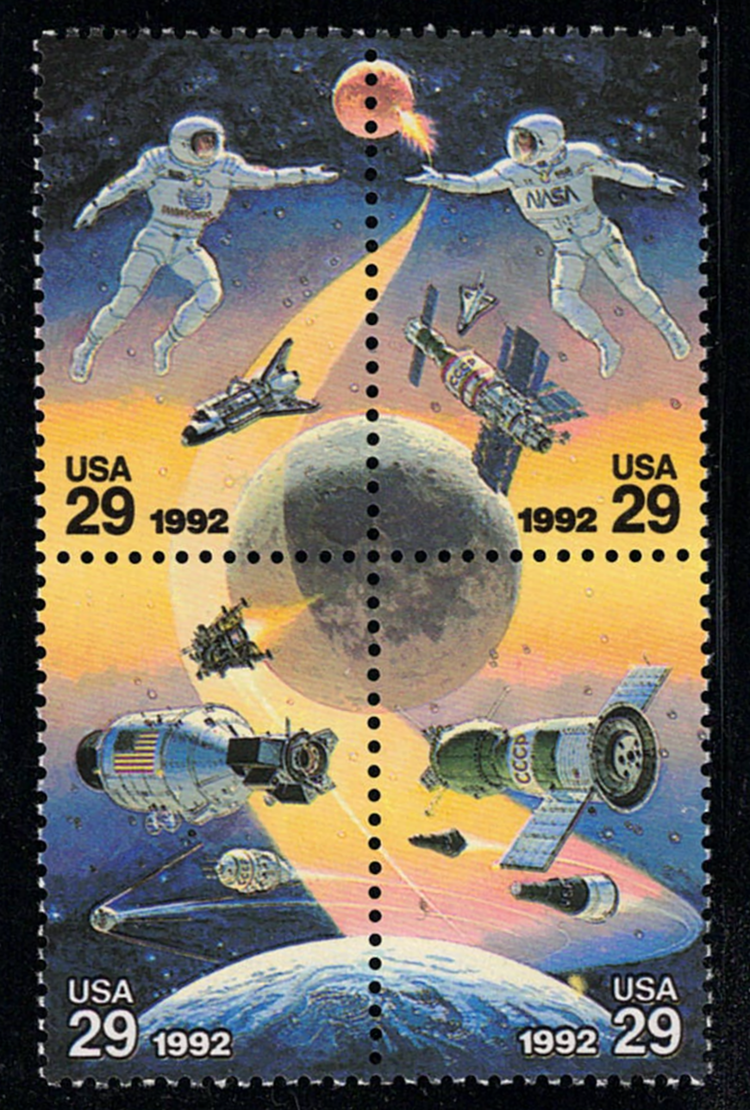

In the third of these sets, the 1992 “Space Accomplishments” issue, four se-tenant stamps celebrate the joint space accomplishments of the U.S. and immediately post–Soviet Russia.Footnote 15 In the two stamps at the top of the group, a U.S. and Russian astronaut reach toward each other across a celestial body that is quartered by the stamps’ perforations, spacecraft hovering beneath them. The two astronauts depicted in the foreground of the top two stamps are so large that it seems impossible that they have any relationship to the much smaller spacecraft in the background; the foreshortening suggests these vehicles are very far away. From where, then, did these astronauts come? And why do they have no way to return to their spacecraft and thereby, to Earth? Moreover, space-suited and awkwardly posed, they seem as much robotic as human. This imagery becomes even more striking when one learns that the stamps’ designers took inspiration from Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, where God's hand reaches out to a naked Adam at the beginning of human time.Footnote 16 Though humans are finally depicted, they are still rendered as fantastical and as subservient to technology. In Fukuyama's phrasing, they are not “meaningful” actors. Here, at the end of history, technology has replaced God and cloaks human actions (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. Space Accomplishments, Russian Cosmonaut, and American Astronaut (1992) (source: Handler's collection).

The bottom stamps show spacecraft with jet lines indicating that they are whizzing toward the left side of the stamp and out of the tableau. Finally, a wavy field emanating from a rocket in the upper-right-hand stamp that appears destined for the celestial body depicted between the two cosmonauts sweeps downward through each stamp, uniting all four. Likewise, the moon is evenly cut into four segments where the four stamps meet. The colors here are equally fantastic: bright yellows and oranges and muted blues and purples. Gone is any sense that space is a dark void (as it had been depicted in the Apollo-Soyuz issue): rather it seems cluttered with planets and spacecraft, again, without any destination or purpose. Further, the fantastical brightness of the color palette and the stamps’ crowded celestial objects and figures highlight the degree to which this stamp is uninterested in realistic depictions of space or space exploration, and rather more devoted to a fictional ethos not unlike that of Star Trek, where enemies become friends and new worlds are mere moments away.

The stylistic features of “Space Achievements” and “Space Accomplishments” go a step further to transmute the history of space exploration and space cooperation into fantasy. The historical facts of space exploration are rendered in futuristic, comic-book style. Indeed, they are oddly similar to the “Space Fantasy” stamps of 1993 and the “Space Discovery” set of 1998. All present faceless astronauts destined for unspecified locations, and rockets and other spacecraft with dramatic propulsion lines redolent of cartoons indicating their speed and maneuverability, but not their destination. All make use of dramatic color schemes typical of science-fiction illustrations, and the se-tenant format to link separate stamps is not used to convey a historical sequence. History has no movement here—instead, the future is dominated by superior gadgets piloted by unseen, and apparently unimportant, human figures (see Figures 12 and 13).

Figure 12. Space Fantasy (1993) (source: Handler's collection).

Figure 13. Space Discovery (1998) (source: Handler's collection).

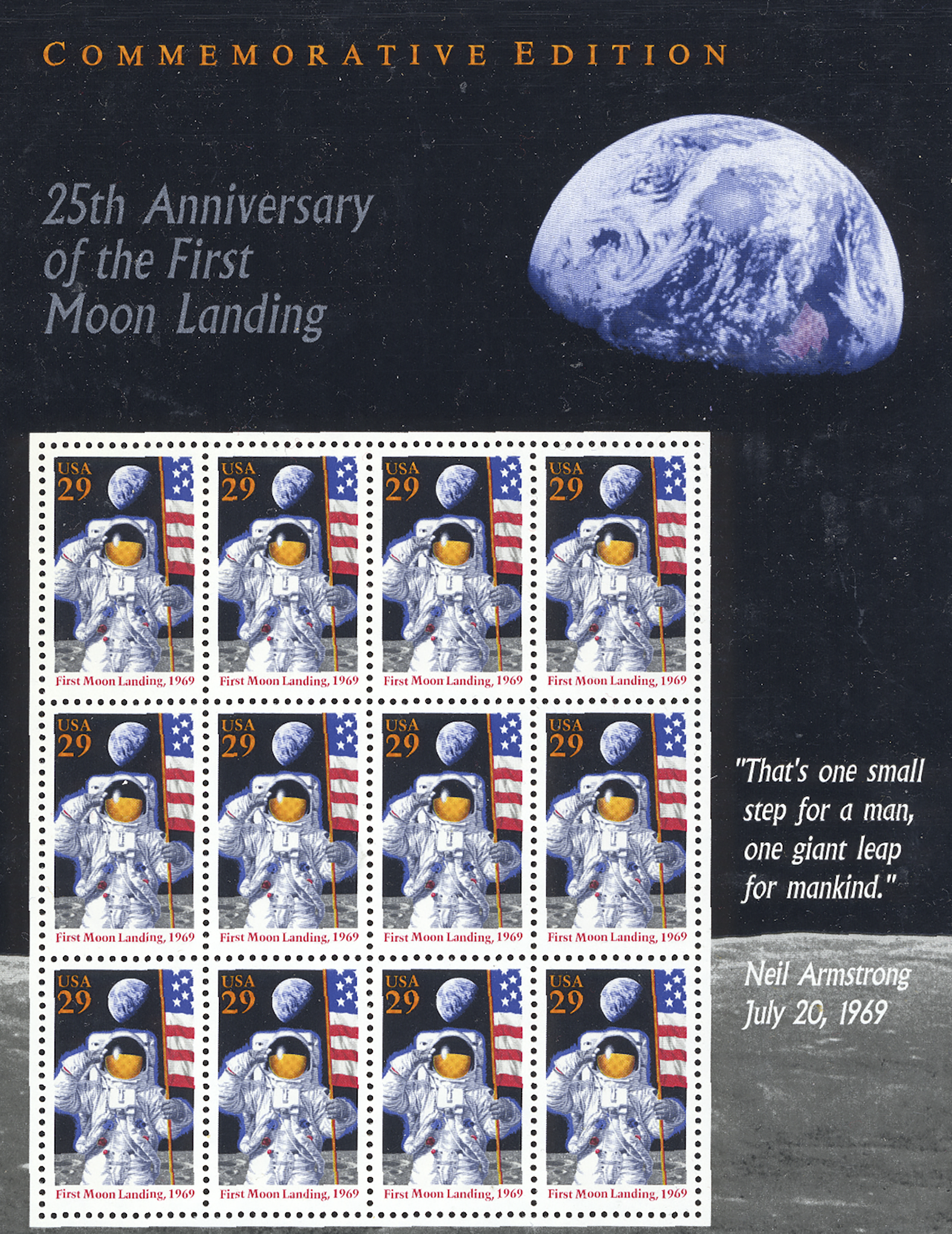

This iconographic tradition of a space future dominated by technology rather than humans continued with the stamp commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. It pictures Neil Armstrong's image of Buzz Aldrin on the lunar surface, though, in his space suit, Aldrin lacks any human identifiers. More startlingly, the reflection off Aldrin's face shield makes the image uncanny. Given longstanding art historical conventions involving mirrors (for instance, Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère and Velasquez's Las Meninas), we should see ourselves reflected by that shield.Footnote 17 In terms of precedent, that reflection often features a white male, something we see in the visor: a figure all in white, in a space suit, whom we know to be Armstrong. And yet if this is a vision of the viewer, then it, too, is an oddly nonhuman and desiccated one, featuring a distant figure in a space suit, the lunar module, and a lengthy shadow. And indeed, this use of the visor reflection has become a favorite theme in Apollo 11 commemorations, such as in the stamps issued for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the mission, although in those instances, the visors reflect nothing but light. The present thus repeats the images of the past endlessly, albeit without human actors as the driving force of change. Instead, we see a proliferation of shiny objects: the visor, the gleaming earth, the flag, the brilliantly white space suit (see Figures 14 and 15).

Figure 14. Moon Landing (2019) (source: Handler's collection).

Figure 15. Moon Landing, sheet of twelve (1994) (source: Handler's collection).

Rings/Moons and the Perils of Corporate Sponsorship

The new gadgets and shiny objects featured in so many of the space stamps we have examined bring us to the second strand of our analysis: the commercialization of the postal service that accelerated when the USPOD was transformed into the USPS. In 1983, when the eagle and the moon were drafted as advertising icons for the postal service's new express delivery products, the USPS had high hopes that its new corporate logo, the graphically rendered eagle (notably, an animal rather than a human delivering the mail), would promote—and thereby help to actualize—a newly streamlined, corporatized, and profitable postal service. The USPS's use of the eagle for its explicit commercialization of its services and stamps occurred again in 1991, when it became a corporate sponsor of the Olympics. In new definitive stamps for Express Mail and the related service, Priority Mail, eagles nearly identical to that used in the first Express Mail stamp were linked not to the moon but to the Olympic rings. Instead of having the eagle's beak jut out over the lunar surface, the eagle floats alongside, above, or below the Olympic logo. Rather than denoting exploration or a fundamental U.S. value, the eagle now advertises a sporting event. It thus becomes a fungible symbol—one that expresses a version of nationalism rooted in the commercial realm.

Unfortunately for the USPS, its pricey corporate sponsorship was not a clear business success. According to a 1993 report of the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), in 1989 “the Postal Service signed agreements with the U.S. and international olympic [sic] committees to be a worldwide sponsor of the 1992 games…. A sponsorship fee of $10 million entitled the Service to use the Olympic rings in its advertising and promotions until the end of 1992.” More specifically, the USPS became an exclusive “product sponsor” in the category of “expedited mail” services (Express Mail and Priority Mail). With this arrangement (which meant that such competitors as FedEx and UPS would be prohibited from using the 1992 Olympics as an advertising platform), the USPS hoped to increase its revenues and profits by “increasing its share of international expedited mail” and by “expand[ing] its philatelic programs” with products related to the Olympics.Footnote 18

It had long been the practice of postal administrations around the world to issue stamps celebrating upcoming Olympics. The International Olympic Committee permitted the inclusion of its logo, the Olympic rings, in these stamps because it provided free publicity. The United States had first released such stamps in 1932 (without the rings) for the Los Angeles Olympics. The first U.S. Olympic stamp bearing the logo was issued in 1960, and after that, many more were made available for purchase.

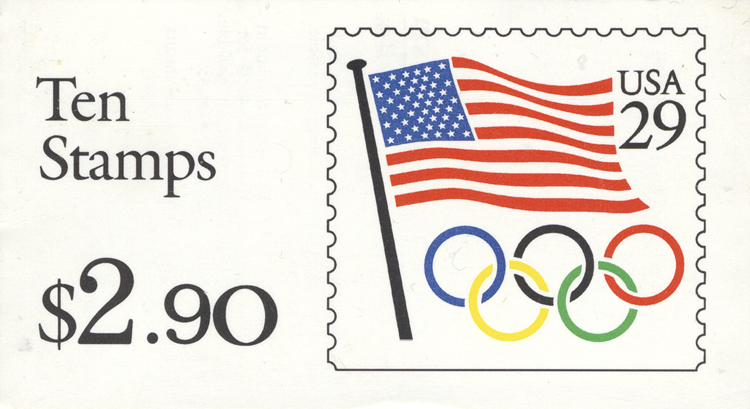

The 1992 USPS Olympic issues differed from prior issues, which all depicted Olympic events and athletes on either commemorative or airmail stamps. In 1991–1992, as a corporate sponsor, the USPS had the right to use the Olympic rings on any of its stamps and other products, whether or not they were thematically related to the games. Thus in 1991, it issued a booklet of ten 29-cent definitive stamps bearing the rings prominently displayed beneath the U.S. flag, thereby advertising the USPS's corporate sponsorship of the games more than the games themselves. The same was the case with the eagles and rings used on the 1991 stamps for expedited mail services. An even more obvious postal device advertising the corporate sponsorship was the slogan cancel used between 1989 and 1992, which read, “U.S. Postal Service/Official Sponsor/1992 Olympic Games” (see Figures 16 and 17).Footnote 19

Figure 16. Booklet of 29-cent definitive stamp bearing Olympic rings (1991) (source: Handler's collection).

Figure 17. USPS Olympics slogan cancel (1989–1992) (source: Handler's collection).

Beyond postal services, stamps, and nonstamp philatelic items, the USPS planned to sell Postal-Olympic–themed merchandise “to the general public.” Its catalog included a wide array of products: clothing, coffee mugs, calculators, clocks, watches, paperweights, playing cards, jackknives, and golf balls all bearing a logo that featured the USPS eagle with trademark immediately to its right, the Olympic rings, and the phrases “USA” and “OFFICIAL SPONSOR”Footnote 20 (see Figure 18).

Figure 18. USPS Olympic-themed merchandise (1991) (source: Handler's collection).

But things did not go as planned. “The U.S. Olympic Committee later informed the Service that such sales would violate the Committee's agreement with another sponsor. The Service was, thereby, limited to selling merchandise to its employees.” And indeed the 1991 and 1992 issues of Postal Life, an in-house magazine for postal employees, featured many advertisements and “catalogs” displaying the merchandise and their prices. The GAO concluded that the USPS's revenues from the sale of such merchandise “amounted to only about $1 million,” whereas “$22 million had been planned” when the USPS took on its Olympics sponsorship. Worse still, from an accounting perspective, although the USPS indeed saw its revenues from expedited mail services increase $43.2 million during the period of its sponsorship, the GAO argued that there was no way to know whether the increase could be attributed to the advertising connected to its Olympics sponsorship.Footnote 21

When a new Postmaster General, Marvin Runyon (a celebrated corporate cost-cutter known as Carvin’ Marvin), took over in mid-1992, he immediately squelched any plans for USPS sponsorship of the 1996 Olympics, which were to be held in Atlanta. It was reported that he was particularly outraged by the fact that the USPS “took to Spain [site of the 1992 summer Olympics] many postal employees, big postal customers and even two chefs to cook for the entourage.”Footnote 22

The upshot is that UPS, one of the USPS's main competitors, became a corporate sponsor of the Atlanta Olympics, with the right to advertise using the Olympic rings. And while “all worldwide postal administrations” were “authorized” to use the rings in postal markings (like cancelations), the USPS was excepted, “since a Postal Service competitor” was “paying to be an official sponsor.” Finally, the USPS was “not permitted on the sites of the Olympic events,” which meant there would be no mail service conveniently available to athletes and souvenir-seekers alike.Footnote 23

But that is not quite the end of the story. By authority of the U.S. Constitution, only the USPS can process and deliver mail. UPS had four well-marked “shipping centers” inside the Olympic “infrastructure” where they sold U.S. postage stamps and several “special delivery” services that approximated letter delivery (but did not technically qualify as such). They also collected mail at these centers—which they then “turned … over to the USPS for final sorting and machine canceling.”Footnote 24

Though Fukuyama predicted that at the “end of history” consumer culture and democracy would be seamlessly unified, the USPS's competition with UPS during the Atlanta Olympics suggests otherwise. That the USPS bungled its corporate sponsorship of the 1992 Olympics and was then effectively banned from the 1996 games speaks to the government's inability to compete with other businesses. Despite the fact that the 1996 Olympics were held on U.S. soil, the USPS struggled to seize the games as an opportunity for self-promotion, as other capitalist entities might.

But it is not just the government's actions that challenged Fukuyama's prediction. So, too, did UPS. Unwilling to allow its competitor—the USPS—to bandy its brand in the Olympic village,Footnote 25 UPS tried to take over postal (or postal-like) services as much as possible, yet still had to rely on the USPS for mail delivery. If we can say that the USPS failed to manage its corporate function, we can also say that UPS failed to recognize the democratic limitations on its business practices.

Fukuyama wrote of a world where to speak of democracy would be to speak of capitalism, and vice versa. Yet instead of seeing these two entities merge, or even coexist symbiotically, space stamps and the USPS's role in the 1996 Olympics show us instead that at the end of history, consumer capitalism threatened to eclipse democracy.