Introduction

Tamil Nadu's chief minister, Edappadi K. Palaniswami, announced his recognition of the Devendrakula Vellalar caste (henceforth, Devendras) at the state level and his plan to recommend corresponding recognition to the union government on 4 December 2020 at a political rally in the southeastern city of Sivagangai (Srikrishna Reference Srikrishna2020; Velmurugan Reference Velmurugan2020; Indian Express Tamil 2020a).Footnote 1 His recommendation was heeded, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced his acceptance of the change in February 2021, less than two months before Tamil Nadu's assembly elections in which the Bharatiya Janata Party (henceforth, BJP), Modi's right-wing Hindu nationalist party, has historically fared poorly (Prasanna Reference Prasanna2021). On 19 March 2021, just 18 days before the election, the Lok Sabha passed the Constitution Scheduled Castes Order Amendment Bill 2021, which legally enshrined the existence of the Devendras (The Hindu 2021a).

The newly recognized caste is constituted by the consolidation of seven localized Dalit castes (called Scheduled Castes in government parlance; henceforth, SC), including the Pallar, Kudumbar, Pannadi, Kaaladi, Kadayar, Vathiriyar (sometimes spelled Pathiriyar), and Devendrakulathar, who are socio-economically and demographically diverse (Senthalir Reference Senthalir2019; The New Indian Express 2020a). Of the seven castes, Pallars are by far the most populous, constituting about 19–20 per cent of the total SC population in Tamil Nadu, while the other six castes together constitute significantly less than 6.5 per cent of the total SC population (Census of India 2001).Footnote 2

Palaniswami's act of official recognition was in immediate response to a one-man commission that investigated communities now classified as Devendras after the political party claiming to represent them, the Puthiya Tamilagam (New Tamil Country; henceforth, PT), led a day-long hunger strike that stretched across the state. Following their leader, Dr Krishnasamy, protesters demanded consolidation and renaming (The Hindu 2020a). The chief minister's gesture cannot, however, be attributed to recent advocacy and activism alone. The PT's mobilization builds on the efforts of activists who have been petitioning the government for official recognition of the Devendras since 1971 and for their removal from the SC list since 1994 (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 125; 170).

The latter half of the demand, which was not met by Palaniswami, remains a point of contention among Devendras and illustrates the tension that troubles their caste-based mobilization. Inclusion on the SC list affords significant material benefits under India's reservation (affirmative action) system, such as increased chances for acceptance into elite educational institutions and highly coveted government posts. However, in an ironic twist that conflates governmental systems of reparation with traditional markers of status and rank, many Devendras reject the SC label. According to Dr Krishnasamy, ‘Remaining in the SC list is a stain. It is akin to being in the River Cooum (a once-pristine river which has turned into the drainage of Chennai) … Only after the British included them in the SC list, these communities have been subjected to caste oppression and discrimination’ (Rajan Reference Rajan2019).Footnote 3

Although rejecting the SC label (and the benefits it offers) is not unanimous among the two to three million individuals who now fall within the Devendra caste, the rejection of antecedent caste titles, especially Pallar, is widespread. As Ragupathi (Reference Ragupathi2007, 59–66) demonstrates in his highly informative doctoral thesis, early twentieth-century caste organizations aimed at social reform and ‘upliftment’ claimed Indrakulathan or Devendrakulathan (‘person of the family of Indra [the king of the Hindu gods]’) as their titles. From the 1970s onwards, such organizations that added Vellalar to their name, making themselves the ‘Vellalars of Indra's lineage’ (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 125). The Vellalars are a relatively high, agrarian, landowning caste who some Pallar populations used to serve. Upending that history, Devendras-in-the-making passed a resolution at a 1971 state-wide conference in Trichy requesting that the government add the Vellalar suffix to their caste title in order to recognize their traditional agricultural occupation (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 125). They thus claimed to embody the agrarian civility of the Vellalars and the Hindu valour of Indra, the king of the gods.

Today numerous caste organizations, political parties, literary groups, scholarly organizations, and other institutions bear the Devendrakula Vellalar title. Nonetheless, audiences that have the power to legitimate the Devendras's mythico-historical narratives have refused to recognize them as they wish to be seen. Even within the new Devendra caste, a contingent of self-styled scholars prefers to be called Mallar rather than Devendra, which has Sanskritic roots (Asirvatham Reference Asirvatham1977, Reference Asirvatham1991; Mallar Reference Mallar2013).Footnote 4 More contentiously, the Vathiriyar, who were added to the Devendra list by the aforementioned government order, have been petitioning and demonstrating against their inclusion in the Devendra caste since 2018, claiming a unique history and culture (Dinamani 2020; Dinakaran 2021; New Indian Express 2020b; The Hindu 2018).

While the Vathiriyars, a very small minority, seem to have been patently ignored, the refusal of dominant castes to recognize the Devendras is more troubling to their process of identity making. The recent protests against the government's recognition of Devendras by Vellalar caste associations, with the support of other dominant castes in Chennai, such as Chettiars and Mudaliyars, demonstrates the urgency and power of such challenges (The Hindu 2021b). In more quotidian contexts, dominant caste Thevars and Udaiyars, among whom I conducted fieldwork in southern Tamil Nadu, continue to call Devendras ‘Pallars', ‘Dalits', and ‘Harijans', even as Devendras persist in their pursuit of authority, honour, and respect by rejecting older monikers that marked their putative inferiority (Gross Reference Gross2017, 116–118).

The argument: Mythico-history, authority, and recognition

In this article, I draw on multi-sited ethnographic and archival research conducted between 2012 and 2014 in Tamil Nadu to examine narrative and embodied processes of collective self-making among the Devendras.Footnote 5 I argue that such processes have been central to the project of Devendra consolidation. I also highlight the economic diversity among the Devendras, which produces divergent political priorities and precipitates the rise of internal tensions between the various communities that are now consolidated into a single caste, according to the state- and national-level governments. Such tensions make the development of revisionist histories particularly important for the Devendras and for other castes against whom they compete because they have the capacity to draw groups and individuals together and to obscure economic differences that would otherwise belie caste unity.Footnote 6

Despite its reference to a different context (Hutu refugees in Tanzania), I employ Liisa Malkki's concept of mythico-history as a heuristic framework for examining Devendra collective self-making (Malkki Reference Malkki1995). Mythico-history, Malkki (Reference Malkki1995, 54–55) argues, is an oppositional ‘recasting and reinterpretation’ of the past in moral terms that makes heroes of its creators and disparages their opponents. For the individuals whose stories unfold in the pages below, mythico-histories generate dignity and rebuff enduring structural and spontaneous violence perpetrated by state actors and locally dominant castes (Gupta Reference Gupta2012; Luce Reference Luce2007). However, the details of Devendra mythico-history are not universally accepted within the recently consolidated caste; instead, Devendra mythico-history is ‘very much a world in the making’ (Malkki Reference Malkki1995, 103).

Within their not-quite established world, most Devendras, nonetheless, share an interest in endowing their caste, and by extension themselves, with authority (atikāram), respect (mariyātai), and honour (mānam), complicating the understanding of twenty-first century experiences of caste developed by David Mosse (Reference Mosse2012) in his ground-breaking, long-term study of caste, politics, and Christianity. Mosse identifies a shift from a focus on honour, rank, and respect in discussions and practices of caste during his fieldwork in the 1980s to a focus on rights articulated through claims to equal access to opportunities upon his return in 2009 (Mosse Reference Mosse2012, 227–228). Describing the new incarnation of caste ‘as a portable form of belonging and connectedness structuring opportunity’, Mosse also identifies inter-caste opposition, which he calls ‘competitive associationalism’, in the rise of caste associations competitively advocating for rights and entitlements (Mosse Reference Mosse2012, 243–245). While competitive associationalism is evident in Devendra mobilization, desires for honour and respect also emerge powerfully and, importantly, such desires are articulated in opposition to other castes that make similar claims projected onto the past.

Aligning with the Devendrakula Vellalar caste title, Devendras's aspirational mythico-histories invoke martial kingship and the classical Tamil virtue of agrarian civility (Mosse Reference Mosse2012, 175–176; cf. Pandian Reference Pandian2009), drawing, in part, on the semiotic resources of Dravidian politics. In so doing, they compete with other castes who make similar claims. The appeal and power of such claims is grounded in their tacit implications, namely that those making them are the rightful, originary rulers and ‘sons of the soil’ of the Tamil country, preceding the nation-state and superseding the assertions of other castes and communities. There is thus a kind of a priori authority, or atikāram, undergirding mythico-historical narratives. Defined as ‘power, authority’ and ‘rule, dominion, sovereignty’ (Tamil Lexicon 1924–1936, 73), the capacious Tamil term atikāram gives us a sense of the various degrees of empowerment, from authority to sovereignty, that Devendras and competing castes seek through mythico-histories.

Regardless of its magnitude, atikāram is troubled by its need for recognition. Like sovereignty, which Danilyn Rutherford (Reference Rutherford2012, 3–4) describes as a utopic ideal that is, by definition, impossible to reach because of its reliance on external acceptance, atikāram requires the recognition of interpellated audiences who themselves exercise authority by shaping the actions of would-be authorities (or even would-be sovereigns). Stuck in this state of Hegelian co-dependence, Devendra claims to authority require that Devendras convince both themselves and members of the broader public of their atikāram. Internal consensus building as a means of collective identity building is, however, challenged by tensions between Devendras with different priorities, and external recognition is even harder to garner. Nonetheless, Devendras seek recognition, which is, in their case, politically empowering.Footnote 7

Devendras's pursuit of recognition by those outside their fold is accomplished, in part, by the recognition they achieve internally, as it brings them together, building their bargaining power by virtue of their size. A telling example of their bargaining power in action unfolds in a recent incident on which The Hindu reported. In mid-October of 2020 (less than two months before Palaniswami's announcement), Kannapiraan, the president of a local Devendra caste association, visited the Tirunelveli Collectorate to submit a petition demanding the name change and the removal of the Devendras from the SC list. It read: ‘This is our demand which alone will wipe out the social humiliation we are now facing for decades. If this demand is not met, the Devendrakula Vellalar voters, who can decide the victory of the candidates of political parties in 20 districts, will exhibit their anger against the ruling AIADMK in the forthcoming Assembly polls’ (The Hindu 2020b).

Asserting their strength as a unified caste with the power to affect election outcomes, Kannapiraan also endows the Devendras with the audacity that would enable them to make such a threat. He thus aligns their contemporary mobilization with their mythico-historical past. Rather than Dalits (literally, ‘crushed’) in need of the government's protection and resources, many Devendras imagine themselves as righteous heroes, who are congenitally courageous and unsusceptible to victimization.

Such attempts to marry the present to the imagined past are, however, challenged by entangled state and dominant caste forces that have the power to underwrite or negate Devendra claims. On the one hand, Devendras must repudiate the power of such forces over them, but, on the other hand, they must appeal to such forces without which their claims to authority remain illegitimate. Devendras implicitly address external audiences in their attempts to make themselves and their world by evoking an extra-institutional dimension of political power—that of the past.

In what follows, I will elucidate the strategic negotiations and oppositional tensions of Devendra identity building. I will first examine the history of Devendras found in the colonial record and trace the development of their mobilization in more recent decades. In so doing, I will highlight Devendras's mimetic, oppositional, and co-constitutive relationship with Thevars, who are also engaged in collective identity building and political mobilization. In the latter half of the article, I will examine the nature of Devendra claims to authority and the leaders that have arisen to make them, homing in on the internal tensions that vex Devendra political strategies and ideologies. I will also elucidate the production of caste identity and political subjectivity in everyday narrative acts of remembering a caste hero. Finally, I will shed light on an important annual ritual event that generates Devendra collective identity, drawing the caste into its consolidated form.

Devendra–Thevar conflicts: historical diversity and revisionist unity

The disavowal of Dalit status by many Devendras, while not unique to them, is facilitated by historical realities that lend themselves to the plausible deniability of antecedent ‘Untouchability’. Unlike other Dalit castes whose names refer directly to hereditary occupations that Brahmanical sensibilities deem polluting, such as Paraiyars (drummers) in Tamil Nadu and Chamars (leather workers) in northern states (Deliège Reference Deliège1997, 123–125), the ‘Untouchability’ of the seven castes that constitute the Devendras is not clearly illustrated by their names or historical occupations. According to colonial administrators-cum-ethnologists of the Madras presidency, such as Edgar Thurston (1855–1935), the name Pallar was derived from the word paḷḷam (meaning low-lying ground) which was either allotted according to their residence or a reference to their place of work, as wet paddy cultivation, in which most Pallar women were engaged, is carried out on low ground (Thurston Reference Thurston1906, 442; cf. Government of the Raj 1890, 37). The close association of Pallars with agriculture, rather than ‘polluting’ forms of labour, supports their present-day denials of Dalit identity. However, as Rupa Viswanath (Reference Viswanath2014) argues, in the nineteenth century, most Pallars were relegated to Untouchability and slavery.

By the turn of the twentieth century, substantial socio-economic differences between and within castes called Pallar, Kudumbar, Kaaladi, Kadayar, and Devendra suggest a more complicated picture. Drawing on the Manual of the Madura District of 1868, Edgar Thurston and his collaborator K. Rangachari claimed that the condition of Pallar agricultural labour was akin to slavery and described the Pallars as a ‘most abject and despised race …avoided by all respectable men’ (Thurston and Rangachari Reference Thurston and Rangachari1909, Vol. 5, 473).

Thurston and Rangachari went on, however, to describe a range of occupations that such castes undertook and to elucidate their access to resources. Drawing on the 1891 census report, they claimed that Pallars in the northwest of the Tamil country were employed in a number of positions, including cultivator, gardener, ‘coolie’ (day labourer), blacksmith, railway porter, tax-collector, office ‘peon’, and magistrate (Thurston and Rangachari Reference Thurston and Rangachari1909, Vol. 5, 474). They also described intricate details of Pallars’ elaborate wedding and death rituals involving gifts of money and the exchange of feasts, clothing, and jewellery, suggesting that not all Pallars were destitute agricultural labours at the time of their study (Thurston and Rangachari Reference Thurston and Rangachari1909, Vol. 5, 480–484).

Colonial accounts of the Kudumbar, Kaaladi, and Kadayar and their relationship to the Pallars provide further evidence of economic diversity within the not-quite-incipient Devendras. At times, Thurston and Rangachari subsumed the Kudumbar, Kaaladi, and Kadayar within the Pallar fold, describing them as sub-castes and titles, but, at other times, they also appeared as independent castes with unique hereditary occupations. They worked, respectively, as headmen of Pallar hamlets, lime shell gatherers and burners (of human bodies?), and agricultural serfs with important duties in lifecycle rituals (Thurston and Rangachari Reference Thurston and Rangachari1909, Vol. 4, 106; Vol. 3, 6 and 52; Vol. 5, 477–480).

Internal diversity is also evident in early identity claims. Thurston and Rangachari listed Devendra as ‘a name assumed by some Pallans, who claim to be descended from the king of the gods’ (Thurston and Rangachari Reference Thurston and Rangachari1909, Vol. 2, 166). They also included Devendra as a Pallar sub-division and recounted this mythological origin story: ‘The sweat of Devendra, the king of gods, is said to have fallen on a plant growing in water from which arose a child, who is said to have been the original ancestor of the Pallans’ (Thurston and Rangachari Reference Thurston and Rangachari1909, Vol. 5, 476). The fact that the Devendra title and corresponding myth were taken up by some Pallars is further evidence of internal variation within what is now becoming a single caste.

Thurston, Rangachari, and a whole army of administrators collecting ethnological data had profound effects on the castes they set out to locate because they encouraged individuals to define themselves according to stable and singular caste identities (Cohn Reference Cohn1996; Dirks Reference Dirks2001). They also allowed such individuals to question and create new categories in the service of their interests. Caste, M. S. S. Pandian explains, took on a new speakability as colonizer and colonized participated in the processes of producing categories, which constituted a shift of caste from the ontic to the epistemic realm and enabled collective negotiations with colonial administrative institutions (Pandian Reference Pandian2007, 10–12). Such epistemological openings expanded even further for the Devendras and many other communities that have experienced the shift to urban lives and livelihoods, departing from rural contexts in which traditional services, like those offered by the Kadayar, were institutionalized.

Negotiations and (re)definitions of caste identity in reaction to colonial policy are evident in the mobilization of the caste formation now known as the Thevars, which is constituted by several ‘caste Hindu’ communities that fall under the Government of Tamil Nadu's Other Backwards Class (OBC) designation.Footnote 8 While ‘Thevar’ is not officially recognized as a single caste by the government, self-proclaimed Thevars’ political influence and their attempts to continue enforcing assiduous forms of Untouchability well into the twentieth century make them the Devendras's greatest opposition. The landowning communities that call themselves Thevars have a long history of oppressing Pallars (the most populous of the present-day Devendras). That history became particularly pronounced when British power waned and the nation lurched towards independence.

While I avoid focusing on Devendra victimization, rejecting the tendency to highlight suffering that Sherry Ortner (Reference Ortner2016) calls ‘dark anthropology’ and aligning my account with the self-image of most of my interlocutors, Thevars’ violent assertion continues to be an important catalyst of Devendra mobilization. The Devendra movement is not, however, an example of Sanskritization (Srinivas Reference Srinivas1962), understood here as self-fashioning according to the ideals of Brahmanical Hinduism, nor a derivative discourse that exists only in reaction to Thevar assertion. Instead, the mutually constitutive opposition between Thevars and Devendras sometimes starts with the latter's formation of caste associations (Mosse Reference Mosse2012, 260) and political assertions, which support their resistance to the former's domination.

From the 1920s through to the 1940s, the initial political consciousness of disparate castes, which would later consolidate into the Devendras, arose, but activism remained disjointed. In Ramanathapuram District in the mid-1920s, local leaders advocated for ‘reform’ and ‘upliftment’, imploring their caste fellows to seek education for their children, and to end ‘backwards’ habits like child marriage, alcohol consumption, and eating crabs and snails (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 60–62). They echoed the self-conscious religious and cultural reform movements that were influenced by the colonial gaze in many parts of British India (cf. Chatterjee 1986, 67–91; Hansen Reference Hansen1999, 71–74; Soneji Reference Soneji2012; Heimsath Reference Heimsath2015). However, in the same district in 1932 and 1934, Pallars advocated for themselves more radically.Footnote 9 Violent conflict erupted between Thevars and Pallars in Ramanathapuram District when the latter refused to accept prohibitions, such as those on the clothing they could wear, their access to education, and their freedom to pursue work outside the bounds of the landlords’ tracts (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 92–93). In 1934, a riot broke out in the same area when Thevars refused to accept Pallars’ modes of temple worship (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 94). Meanwhile, in Thanjavur in 1936, a Devendra conference called for a much more conservative approach, passing a resolution ‘exhorting their people not to oppose landlords, … [and to] follow traditional values and obey the orders of the landlord’ (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 73).

Devendras's changes in religious affiliation further elucidate their diverse political strategies and their historical formation in opposition to Thevars. Christian conversion from the 1890s onwards held out the promise of upward mobility in the southern reaches of the Tamil country, which was sometimes delivered through missionary education leading to employment (cf. Hardgrave Reference Hardgrave1969; Mosse Reference Mosse2012).Footnote 10 Christianity did not, however, diminish practices of Untouchability, a fact that led some Christian and some Hindu Pallars to convert to Islam in the 1940s. In what are now Tirunelveli and Ramanathapuram Districts, more than 2,000 Pallar families converted to Islam between 1945 and 1947, eliciting a violent response from right-wing Hindu nationalist organizations, including the Rashtria Swayamsevak Sangh, the Hindu Maha Sabha, and the Arya Samaj (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 77–78; Manikumar Reference Manikumar2017, 59). After failing to reconvert the Pallars to Hinduism through propaganda campaigns, members of such organizations enlisted Thevars to help them violently attack the newly Muslim families (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 78).

Alongside their violent assertion, which continues today, Thevars began claiming political power by assimilating separate but affiliated castes into the unified Thevar caste, which is now well known in popular parlance. At the broadest level, the Thevar caste formation, which also calls itself the Mukkulathor (roughly, ‘three united clans’) is constituted by the Maravars, Kallars, and Agamudaiyars who appear as different castes in colonial records and in the nomenclature of contemporary governance.

Historically, the Maravars were a clan of hereditary chieftains, some of whom ruled a kingdom of 2,000 square miles in what is now the southeasternmost region of Tamil Nadu (Price Reference Price2013, 20–21). Called the Sethupathis (guardians of the bridge), Maravar chieftains presented themselves as fierce warriors, but simultaneously paid tribute to and supplied troops for the Nayakkar kings who ruled from Madurai from the mid-sixteenth through to the mid-eighteenth centuries (Bes Reference Bes2001, 556; Price Reference Price2013, 20–21). Maravars beyond the Sethupathi fold and Kallars (literally, ‘thieves’) played martial roles through the indigenous mode of policing—the kāval (protection) system—which allowed them to earn income and ‘power, social status, and prestige’ (Ravichandran Reference Ravichandran2008, 1–3). The Agamudaiyars (householder or landholder) lacked royal lineages and have comparatively less violent histories, but their affiliation with Maravars through marital arrangements afforded them the benefits of high status (Government of the Raj 1890, 30).Footnote 11

The British Permanent Settlement, the dismantling of the kāval system, and the criminalization of wide swathes of the Kallar and Maravar populations under the Raj (Price Reference Price2013, 19–25; Pandian Reference Pandian2009) diminished the power of all three communities and created conditions ripe for their unification against the British. Taking advantage of such conditions, Muthuramalingam Thevar (1908–1963), a wealthy landlord, self-fashioned Hindu renunciant, and Indian nationalist, began raising his voice on behalf of ‘the Thevars’, rhetorically consolidating the Maravars, Kallars, and Agamudaiyars.Footnote 12 He appealed to their frustration at their profound socio-economic losses under the weight of colonial rule and spoke out strongly against criminalization, staging demonstrations, which eventually led to the repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act in 1949 (Price Reference Price1996, 192). Early in his political career, Muthuramalingam was vehemently opposed to colonial rule and joined the Indian National Congress, which he then left to join the Forward Bloc, a leftist, nationalist party formed by a schism in the Congress (Lok Sabha Secretariat 2002, 3–4).

Muthuramalingam's ability to unite the three castes depended, in part, on the revisionist histories he promulgated. He recast colonial criminalization as a remnant of the Thevars’ kingly, martial past that evidenced their valour and honour in the present (Damodaran and Gorringe Reference Damodaran and Gorringe2017, 3).Footnote 13 In his public life, he adopted the symbolic strategies of royalty, such as public beneficence (Price Reference Price1996, 193) and declared that ‘the Maravars were the rulers of the country and they alone were entitled to rule the country’ (Manikumar Reference Manikumar2017, 65). In addition to Tamil kingship, nascent articulations of Hindutva, which continue to influence Thevars, were reflected in Muthuramalingam's self-stylization.Footnote 14

Muthuramalingam's performative production of unified Thevar caste pride was intertwined with his political mobilization. In the context of the 1957 state assembly by-election in which he ran on the Forward Bloc ticket,Footnote 15 Muthuramalingam forcefully denigrated the Congress Party and those who supported it, namely Pallars and Nadars (Government of Madras 1957b).Footnote 16 His rhetoric translated into what the government called ‘communal ill-feeling’ (Government of Madras 1957a). Government agents monitoring Muthuramalingam recalled that his ‘inflammatory speeches incited his community men to harass the Nadars and Harijans [Devendras and probably also Paraiyars]’ (Government of Madras 1957a). Government records also refer to an increased influx of petitions from ‘Harijans’ claiming that Thevars had been harassing them and interfering with crop production (Government of Madras 1957a).

Around this time, the incipient Devendra Movement was led by Perumal Peter, a Lutheran convert who called for caste solidarity and, above all else, the upliftment of Pallars through education, and by Immanuvel Sekaran (1924–1957), a youth Congress leader and participant in the Quit India Movement who briefly served in the Indian National Army (Iyer Reference Iyer2016; Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 101–103). The latter adopted a more radical approach, directly addressing Thevar domination. He taught Pallar youths self-defence and openly rejected Thevar attempts to wield authority through the performative, ritual receipt of first respects at temple festivals (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 103). He paid homage to Ambedkar and insisted on the importance of institutional political power (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 104).

Immanuvel's radical, rights-oriented Dalit activism still echoes in the Devendra Movement that has developed in opposition to Thevar assertion. Starting with the Mudukulathor Riots (also called the Ramnad Riots), which broke out during the aforementioned 1957 by-election, recurrent attacks by Thevars, sometimes with the complicity of state forces, have increased Devendra political consciousness.

Returning to the by-election in 1957, the Collector of Ramanathapuram convened a peace committee on 10 September to ease rising intercaste tensions that coincided with Muthuramalingam's campaigning. Both he and Immanuvel participated, and in so doing, clashed in a now famous incident upon which the government reported:

During this conference, an altercation took place between Sri Muthuramalinga Thevar and Sri Emmanuel, a Harijan leader, which would indicate the attitude adopted by Sri Muthuramalinga Thevar and his followers to the Harijans of that area … The incident is that Sri Muthuramalinga Thevar is reported to have asked Sri Emmanuel, Secretary of the Harijan Welfare Association, Mudukulathur, at the conference whether he could pose himself as a leader of the same stature as himself and whether his assurances on behalf of his community were worth having. Sri Emmanuel seems to have retorted that though he was not of the same stature as Sri Thevar yet[,] he could represent his community and speak on its behalf (Government of Madras 1957a).

The following morning, while waiting to transfer buses in Paramakudi, Immanuvel was assaulted and killed by a group of men wielding sickles and sticks (Government of Madras 1957a; Government of Madras 1959). Muthuramalingam and 11 others were accused in the case.Footnote 17

Violence broke out a few days after Immanuvel's murder. While an analysis of the documented cases of violence during the riots is beyond the scope of this article, their brutality and scale make this one of the deadliest conflicts in modern Tamil history (Government of Madras 1957a). Government records attribute the riots’ outbreak in Arunkulam, a village about 20 kilometres outside of Paramakudi, to Devendras's opposition to the public performance of a song praising Muthuramalingam (Government of Madras 1957a). In this case, as in the caste-based identarian claims I analyse below, the aesthetic occupation of public space with assertions of caste pride sparks competitive animosity.

I want to point out here the interplay of symbolic and physical opposition between Devendras and Thevars. Thevar assertions of honour and respect sparked the Mudukulathor Riots in the first place and appear even earlier in Immanuvel's rejection of Thevars’ receipt of first respects at temple festivals, as mentioned above. Rather than rights alone, we find the ongoing opposition between Thevars and Devendras articulated in competitions over symbolic resources through which they both lay claim to markers of caste distinction (cf. Mosse Reference Mosse2012, 164–166). More recently, Muthuramalingam's construction of Thevars’ shared royal past has evolved into claims of descent from the three dynasties of the medieval Tamil country—the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandiyas—and also from the king of the gods, Indra. The same claims are made by the Devendras in their public statements and publications of caste histories (Asirvatham Reference Asirvatham1977; Reference Asirvatham1991; Mallar Reference Mallar2013; Siddhar Reference Siddhar1993; Reference Siddhar2001).

From victimization to victory: Establishing heroic authority

While Devendras attempted to organize immediately following the riots, the heterogeneous goals of various groups, ranging from status recognition to labour rights, thwarted unification in a manner reminiscent of the earlier period of mobilization between the 1920s and 1940s (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 112 and 123–129). Nonetheless, ongoing dominant-caste violence inspired the rise of Devendra leaders whose reach extended beyond their own locales.Footnote 18

John Pandian (henceforth, ‘J. P.’) began his ascent when he was a college student. He and an attorney, Ashok Kumar (who later became a Madras High Court judge), led a demonstration of approximately 5,000 in 1980 to express their anger at the government's failure to react to the rape of a Pallar woman and the murder of her husband, as well as the broader pattern of dominant caste sexual violence that had terrorized Pallars in and around Tirunelveli District for generations. Before the rally could officially commence, the crowd, which gathered in the small city of Tirunelveli, was dispersed by the police. They arrested J. P. and Kumar, who, according to a local reporter, shouted that they were following the path laid by Immanuvel Sekaran (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 133). The demonstration and its fallout set the tone for J. P.'s political style, which is marked by aggressive language, and calls for the ‘eye for an eye’ approach (in J. P.'s words, ‘a hit for a hit’).Footnote 19

Around this time, Pallar conversions to Islam again elicited violent reactions of Thevars led by the forces of Hindutva. After the conversion of 180 Pallar families in Meenakshipuram in 1982 caught the attention of the nation, the Hindu Mannani and Arya Samaj established regional campaigns to present conversion as a threat to national security and integrity. They organized Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (henceforth, RSS) rallies in southern Tamil Nadu and instigated attacks by Thevars clad in RSS uniforms who were supported by police in Tirunelveli and surrounding areas (Ragupathi Reference Ragupathi2007, 136–139).

That same year, Dr K. Krishnasamy, a middle-class medical doctor, began his rise to prominence as a Devendra leader (Vaasanthi 2006, 202).Footnote 20 He joined the militant Dalit Panthers Iyakkam (henceforth, DPI)Footnote 21 at the moment of its establishment in 1982, when it was a revolutionary collective (that is, not a political party) aiming to eradicate Untouchability and caste ideology writ large (Waghmore Reference Waghmore2012; Lerche Reference Lerche2008).Footnote 22 In the early 1990s, Krishnasamy split from the DPI, which had become an active political party, the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (henceforth, VCK). He attributes this fracture, somewhat cryptically, to the refusal of Paraiyars to cooperate and, more plainly, to the hereditary occupational differences between Devendras and Paraiyars (Vaasanthi 2006, 204).Footnote 23 After the split, Krishnasamy won in a Legislative Assembly election in 1996 and established the predominantly Devendra PT political party in 1997, which gained popularity in the context of another Thevar–Devendra conflict (Vaasanthi 2006, 201).Footnote 24 Krishnasamy was elected to the Legislative Assembly again in 2011, but, unlike the VCK, he has not been electorally successful more recently.Footnote 25

Krishnasamy's decline may be attributed, in part, to his wariness of caste fellows who fail to align with what can best be described as his class status. In 2012, a few weeks after violent clashes between Devendras and Thevars led to false accusations and arrests in Ramanathapuram district, I managed to get an appointment with Dr Krishnasamy in Coimbatore, a prosperous town in the northwest of Tamil Nadu and his native city. I arrived at the hospital he and his wife founded and was greeted by a receptionist and a not-too-long wait. When I was ushered into his office, Krishnasamy looked up from his desk, which was piled with neatly stacked papers, and, in English, invited me to sit down. I asked Krishnasamy a few broad questions about the events unfolding in the state's southeast, such as ‘What do you think about the situation (sunilai) in the Paramakudi area?’ Mostly in English, Krishnasamy's reply revealed the complicated internal dynamics that trouble the formation of the Devendras as a single caste. He began evenly,

Down there, there are some rowdy elements. They will get into fights with the young fellows of other castes. One side will say, ‘we're the big ones’ [periyavaṅke], and then the other side will say, ‘we're the big ones.’ They fight senselessly, and then there are some problems with the police. It is a very rough area, and it is also poor so there is not much employment. The men stand around on the road and at tea stalls, so some fights arise … There is not much that I can do about such things. There is nothing that I can do by going there … I am an MLA (Member of the Legislative Assembly) and work with the government to improve the economic situation.

Krishnasamy then shifted to a discussion of the PT. He told me about the establishment of the party and about their petitions to officially change the Pallars’ caste name to Devendrakula Vellalar, which have finally yielded results. The authority Krishnasamy claimed was rooted in his institutionalized status emerging from his official government position and his role as a well-to-do medical doctor. His stance was not an affront to ‘the establishment’, but was rather aligned with the well-worn moderate approach of effecting change from within.

Krishnasamy's mobilization is troubled by his competition with J.P.'s Tamizhaga Makkal Munnetra Kazhagam (Tamil People's Progress Party; henceforth TMMK), which was established in the late 1990s but was mostly dormant during J. P.'s imprisonment between 2002 and 2010.Footnote 26 Mutual animosity colours the relations between the two leaders, who describe each other as ‘waste’ (that is, ineffective and useless). Such intracaste antagonism, compounded by both parties’ adaptive electoral alliances with the hegemonic DMK, AIADMK, and even the BJP, leaves many Devendras sceptical of the possibility that their lives can be improved through the institutions of electoral democracy. Rather than putting their faith in party politics, disenchanted Devendra populations evoke the past to energize claims to authority in the present. A significant contingent of Devendras claim atikāram through revisionist histories. Such claims are, I contend, essential to their empowerment vis-à-vis the government and other castes, as it affords them the substantial power in numbers yielded by consolidation.

Despite the diversity of the Devendras, they consistently situate themselves within a collective past characterized by righteous heroism and exemplified by the life of the aforementioned caste leader Immanuvel Sekaran. He was by far the most common point of reference when I inquired about the Devendras's history and identity, and in my observations of everyday interactions in homes, community centres, and public spaces. More broadly, the story of Immanuvel circulated through conversations, songs, social media posts, YouTube videos, popular artistic representations (on and offline), quotidian conversations, self-published tracts, and ritual performances.

The version of Immanuvel's story recounted to me by Ponnammal, a Devendra retired principal residing in Paramakudi, is typical. Sitting on the cool granite floor of her neatly swept house during one hot and bright morning in 2013, Ponnammal presented Immanuvel's story with the narrative amplitude described by Walter Benjamin (Reference Benjamin, Benjamin and Arendt1968 [1965], 89). The art of storytelling, Benjamin (Reference Benjamin, Benjamin and Arendt1968 [1965], 89) explains, does not involve the dissemination of information (raw data), but instead relays an experience that is shared in the moment of telling. This tale was not explained didactically or reflected upon with extra-narrative comments by Ponnammal or other interlocutors. It was relived in the tone and tenor of the voices and movements that recounted it.

Ponnammal loudly and slowly explained what she sees as a very clear-cut chain of events. ‘There was Immanuvel, right, and he and Thevar [Muthuramalingam] were at a meeting in Mudukulathor [sic].’ ‘The Congress meeting, right?’ I asked misguidedly.Footnote 27 Ponnammal continued evenly:

Yes, and they were both in the Congress. You see, Thevar came in and Immanuvel did not stand up. He sat, like this, with his legs crossed, and his foot pointing towards Thevar. Like this! … And Thevar said something wrong and Immanuvel extended his hand like this, like this. No one else would say anything except for Immanuvel. But then they [the Thevars] got mad at his audacity (tairiyam), at his heroism (vīram).

Ponnammal narrated the story with her body, sitting ‘like this’ with her legs loosely crossed, extending her hand and her index finger (as if scolding) with the zeal that she attributed to Immanuvel. She mimetically embodied Immanuvel's rejection of Thevar supremacy and his own ‘Untouchable’ subjectivity, actively participating in his courageous subversion.

Muthuramalingam's status as an older, wealthy landlord and successful politician set the normative imperative for the younger and lower-caste Immanuvel to stand when the former entered the space of a gathering. In addition to his failure to rise, Immanuvel's crossed legs, we are to assume, would have offended Thevar. While sitting with one's legs crossed is not an act of assertion in and of itself, socially, it can signify the cross-legged individual's superiority over co-present others whose feet remain more humbly affixed to the floor. Even more offensive to Thevar sensibilities is the idea that Immanuvel pointed his foot and finger at their leader. Pointing your foot at someone is an act of aggressive disrespect and insult in South Asia and pointing one's index finger at another is again a sign of superiority, akin to a mother or boss wagging their finger in scolding.

When remembered and relived, such subversive corporeal acts are hyper-potent signs of resistance to generational Thevar domination and mythico-historical narratives that create and consolidate collective identity. Ponnammal and her caste fellows’ narratives unite individuals through their performative experiences of liberatory defiance, despite their widely varying socio-economic circumstances. Ponnammal, for example, is well off relative to her neighbours and to her rural relatives and caste fellows. She receives a pension from the government and benefits from the financial comfort of her daughter who is married to a government-employed engineer. Nonetheless, her affectively powerful recounting of the story of Immanuvel narrates her belonging as a Devendra (cf. Simpson 2014, 15 and 209).

The heavily moralized tale of Immanuvel, which is repeated often at formal and informal gatherings throughout the state, produces the Devendras as a collectively defined subject by building a mythico-historical consensus on the past. As Malkki explains, mythico-history is a process of world making that consolidates collective identity by educating, explaining, prescribing, and proscribing; it helps the communities it constitutes confront the past and the pragmatics of everyday life (Malkki Reference Malkki1995, 54). For Devendras, confrontations of the past manifest in strategic citations that disavow degradation and Untouchability and stake a claim to righteous and honourable heroism.

Needing all the help they can get in this discursive struggle, Ponnammal and others draw on the powerful aesthetico-political ethos of Dravidianism, the multivalent twentieth century ‘Southern’ movement that began as a rebellion against Brahman, North Indian, and orthodox Hindu power, but which evolved into a less socially radical articulation of retrotopic Tamil pride (Damodaran and Gorringe Reference Damodaran and Gorringe2017, 3; Bate Reference Bate2009; Ramaswamy Reference Ramaswamy1997; Subramanian Reference Subramanian1999; Pandian Reference Pandian2007). Broadly popularized by the celluloid images, print-mediated discourses (Cody Reference Cody2015), and performative practices (Bate Reference Bate2009) of two Dravidian parties, which have been electorally challenged only by each other since 1967, Dravidianism defines what it is to ‘do’ politics in Tamil Nadu (Gorringe Reference Gorringe2011). In so doing, it equates political authority, atikāram, with behavioural and ideological ideals exemplified by its leaders, namely, vīram (heroism), mānam (honour), and māriyatai (respect).Footnote 28 In the Dravidian ethos that endures today, vīram appears as the sine qua non of the trifecta, as it is required to achieve and protect honour and respect (Price Reference Price2013, 160–1).

While such ideals were articulated in pre-colonial political practice in the Tamil country, they gained widespread appeal as central themes of Dravidian propaganda between the 1940s and 1960s (Price Reference Price1996, 143–178).Footnote 29 Widely popular Dravidian leaders, drawn from the burgeoning Tamil film industry, including Marudhur Gopalan Ramachandran (1917–1987) and Muthuvel Karunanidhi (1924–2018), presented themselves on screen and in person as embodiments of the glorious Tamil past (Bate Reference Bate2009), as well as righteous revolutionary heroes who would stop at nothing to protect the Tamil people (Prasad Reference Prasad2014; Pandian Reference Pandian2007; Dickey Reference Dickey1993). Around the same time, true stories of young men self-immolating in protest against the attempted imposition of Hindi in schools and government institutions circulated (Ramaswamy Reference Ramaswamy1997). Tamils of various ages and statures joined together in the spirit of vīram that had been generated by Dravidianism.

Nonetheless, Dravidianism ultimately failed to create a unified non-Brahman Tamil coalition, as Dalits were excluded from its centre and responded with the development of their own political movements (Pandian Reference Pandian2007, 196). It is thus not surprising that many Devendras avoid aligning with the dominant Dravidian parties and instead appropriate and deploy Dravidian behavioural ideologies as their own. Over the course of my fieldwork, I found that vīram (heroism), mānam (honour), and māriyatai (respect) featured prominently in discussions of effective Devendra leadership and mobilization, and in narratives about the longer history of the community.

Ponnammal closed her account with a direct reference to the ultimate act of heroism—martyrdom (tiyākam). She asserted Immanuvel's vīram even in his defeat and death. Drawing a line across her neck, above which she bore an exaggerated grimace, Ponnammal told me that ‘they killed him, those goondas [ruffians], right over there … at the bus stop. He was a great martyr for our community’ (samuthāyam). When Ponnamal and other Devendras tell the story of Immanuvel, they endow his ultimate sacrifice with honour and righteousness, appropriating the power of heroes remembered in Tamil political and cultural history in order to repudiate narratives that highlight their historical oppression as Dalits.

While my Devendra interlocutors consistently referred to Immanuvel, emphasizing his transgressive, corporeal rejection of Thevar domination and his subsequent martyrdom, they minimized the outbreak of violence that followed. As mentioned above, the Mudukulathor Riots erupted in the wake of Immanuvel's murder. Despite the fact that some of my interlocutors lived through them, I usually had to refer directly to the riots (kalavaram) in order to hear anything about them. Devendras, in their refusal to focus on their victimization during the riots, construct the collective memory of heroism upon which their consolidated caste relies and align themselves, as individuals, with the primordial vīram they attribute to Immanuvel.

What I aim to point out here is the way in which Devendra mythico-history functions as world making. Despite the destruction of Devendra lives and property that is clear in government records and which continues in the twenty-first century, Devendra mythico-histories rhetorically refuse the victimization that powerfully shapes Dalit political mobilization in many parts of the subcontinent. We must not understand Devendra narratives as ‘singular … but, rather, as [part of] the reiterative and citational practice by which discourse produces the effects that it names’ (Butler Reference Butler1993, 2). They present (and thus phantasmically constitute) themselves as righteous rulers and fierce heroes, carrying glimpses of the (imagined) past into the present.

Ritual remembrance: Constructing caste in the past

While Devendras's assertions are circulated in a wide range of contexts, one particular annual event, commonly known as the Tiyāki Immaṉuvēl Tēvētiraṉ Niṉaivu Viḻā (Memorial Festival of the Martyr Immanuvel Devendran), plays a crucial role in their collective identity-making. Celebrated annually on 11 September in Paramakudi, the event has grown steadily and significantly since the late 1980s and now attracts thousands of Devendras, as well as various political leaders and party cadres from across the state (and sometimes country).

Although I focus on the Niṉaivu Viḻā in what follows, it is not the only annual event celebrated by the Devendras. There are thematically comparable and similarly structured events that have increased in popularity in recent decades, including memorial events celebrating Veeran (literally, ‘hero’) Sundaralingam, a late eighteenth-century Pallar fighter loyal to the Nayaks who died resisting the British East India Company (Pandian Reference Pandian2000), and the modern-day Devendra leader Pasupathi Pandian, who was murdered by political rivals in 2012 and is now widely considered a martyr. Even the annual celebration of the Sataya Viḻā, the birth anniversary of the tenth-century king Rajaraja Chola, has become a space for Devendra assertion. Since at least 2011, Devendra and Thevar (and Vanniyar) activists have deployed ritual assertions of their royal lineage at the Sataya Viḻā, but they have, luckily, avoided each other, descending on Thanjavur on different days during the three-day celebration.

While status claims are conspicuously articulated at Devendra memorial events, the history of the Niṉaivu Viḻā demonstrates that status aspirations were not always at the heart of Devendra mobilization. My interlocutors and the journalist Muthukaruppan Parthasarathi agree that Immanuvel was first ritually memorialized in 1958, but the event began attracting state-wide attention with the help of radical Dalit political leader P. Chandrabose in the late 1980s (Parthasarathi Reference Parthasarathi2011; Geetha Reference Geetha2011). During a long interview in his sparse home in Paramakudi, Chandrabose claimed, ‘the reason for this function [Niṉaivu Viḻā] is really me!’ While the leadership of the state SC/ST Employees Association in organizing the event means that its development cannot be attributed to Chandrabose alone, the underlying goals of Dalit solidarity and the destruction of caste that he propounds ensure that he and the Employees Association are ideologically in sync.Footnote 30 Chandrabose's vision for the event is reflected in the organization he established in 1988,Footnote 31 the Tiyagi Immanuvel Peravai (Martyr Immanuvel Union), which rests on an atheist, materialist, and universalist Dalit human rights platform, and its public statements and monthly magazine, Māṟṟam (Change), tend to focus attention on violence against Dalits from a range of communities. Running counter to revisionist histories of heroism, Chandrabose recently told the Hindustan Times reporter Aditya Iyer (Reference Iyer2016) about caste oppression and assiduous practices of Untouchability in the Paramakudi area.

Crucial for my argument that diverse strategies vex Devendra consolidation is the appearance of Immanuvel as an early icon of Dalit unity aimed at destroying caste writ large. Chandrabose told Iyer that Immanuvel fought for ‘equality for all’ and showed Dalits throughout the state the way to unify and mobilize (Iyer Reference Iyer2016). Iyer also quotes Dalit intellectual and historian Stalin Rajangam, explaining that Immanuvel ‘reemerged as a powerful symbol for the Dalits in this state … in the late 80s and early 90s … [in order] to unite the Dalits in the state under one banner’.

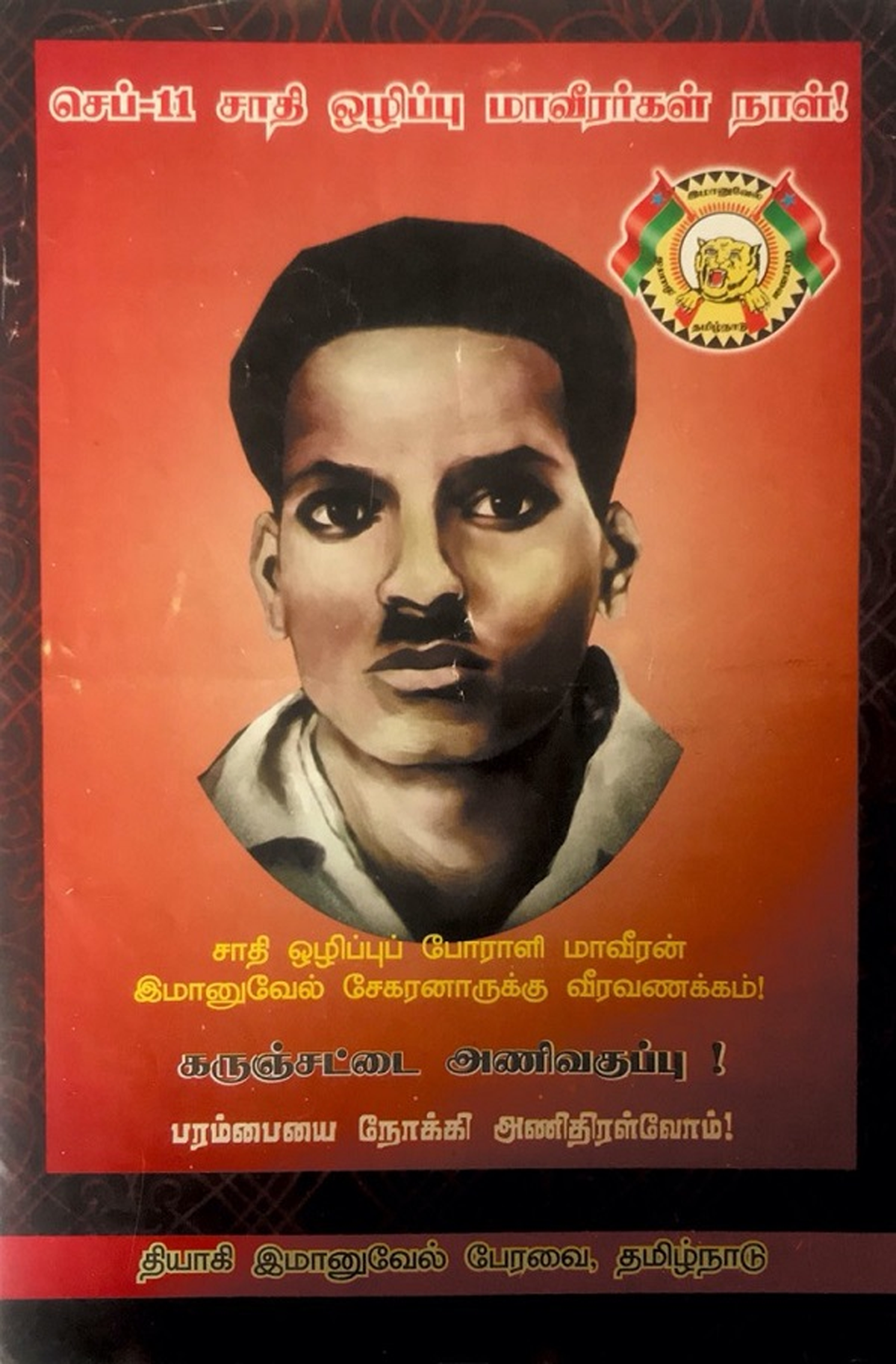

Chandrabose himself remains steadfast in his commitment to Dalit unity and his complementary rejection of status aspiration. During the aforementioned interview, his wife walked by and he pointed out that she does not wear jewellery, which is, in the Tamil context, a ubiquitous marker of prestige and status. ‘We desire the equality of all,’ he remarked, handing me the August/September 2013 issue of Māṟṟam. I noticed on the back cover an advertisement for the upcoming Niṉaivu Viḻā, which was described in telling language as ‘Cāti Māvīrarkaḷ Oḻippu Nāḷ’ (‘Great Heroes' Destruction of Caste Day’) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Māṟṟam magazine August/September 2013, back cover. Source: The author, 2021.

The advertisement also featured a sketch of Immanuvel's bust below which the following text was printed: ‘Hail to the great hero Immanuvel Sekaran who fought for the destruction of caste’.Footnote 32

While many Devendras have moved away from Chandrabose's socially radical platform, the endurance of multiple conceptions of Devendra identity is evident in the semiotic repertoire of the Niṉaivu Viḻā's recent iterations. In the days leading up to the event, didactic visual and auditory signs telling the story of Devendra valour and honour become increasingly dense, so that on the day of the Niṉaivu Viḻā, Devendra presence overwhelms the space of Paramakudi.

In part constituting Devendra semiotic saturation, throngs of participants arrive on foot, on motorbikes, and, more rarely, in cars, usually carrying banners bearing the names of their caste organizations, villages, or political parties (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figures 2 and 3. Participants at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: The author, 2012.

They form a parade, making their way down the town's main thoroughfare towards Immanuvel's ten-foot-long black granite gravestone, which is referred to as his samadhi.Footnote 33 Journalists and an attentive crowd watch as groups approach the samadhi, garlanding it with heavy strands of flowers and performing añjali—a sign of reverence and worship undertaken by raising one's hands and joining them together in prayer position at the chest or above the head. Announcers from Paramakudi's largest caste organization, which plans the Niṉaivu Viḻā, narrate these acts of ritual reverence, so that all groups receive recognition, followed by applause and cheers.

While respects are paid at the samadhi, the party continues along Paramakudi's main road (see Figures 2 and 3). The visceral tone of the festivities is assertive, even aggressive, as songs that recount the glories of caste history blare through heavily amplified speakers and groups of men dance feverishly to the rhythms of the big drums beaten by their compatriots. Explosions of firecrackers intermittently add to the percussion, and the visual horizon is filled with loud flexboards and cut-outs featuring Devendra heroes (and aspiring heroes) of the past and present (see Figures 4 and 5).Footnote 34 Some of the signs are sponsored by political parties, but most of them are financed by caste-based organizations in various locales, which announce their sponsorship in the largest and most colourful fonts.

Figure 4. Flexboard of Immanuvel at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: Author 2012.

Figure 5. Flexboard of Immanuvel in various forms at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: Author 2012.

In addition to heralding the reach of Devendra identity across the state, the superabundant marking of public space with Devendra signifiers asserts the caste's greatness through what Bernard Bate calls ‘sensory saturation’ and Diane Mines describes as ‘density’ (Bate Reference Bate2009, 80; Mines Reference Mines2005, 163). In her analysis of Tamil temple festivals, Mines (Reference Mines2005, 163) locates density in material excess manifest in enormous offerings of food and other valuables that together are converted by worshippers into a scale of value: ‘The scale may be understood as relative “bigness” (perumai), and village residents display it and openly compare it hierarchically’. In the context of Mines’ (Reference Mines2005) study, a high value of perumai bespeaks the power of the god to effect change in the world, as well as the prestige of the village. In the world of (at least officially) secular politics, the employment of density as an iconic signifier of perumai follows the same logic. Public political meetings of Dravidian parties, Bate (Reference Bate2009, 78) explains, are characterized by excessive numbers of repetitive signs lined up one after the other, which saturate the viewer's visual field. Aural signs, like blaring loudspeakers, are also part of the sensory saturation that Bate (Reference Bate2009, 78) recalls overwhelming his body. Together, the degrees of visual and aural saturation are ‘directly proportional to a particular organisation's or individual's “greatness” (perumai), “name” or “renown” (peyar) … “weight” (kanam), etc’ (Bate Reference Bate2009, 78).

Such assertions of status underwrite Devendra claims to atikāram by articulating their ability to make them, and iconically and materially signifying their achievement of control (even if temporary) over public space. The Niṉaivu Viḻā thus simulates the actualization of atikāram, understood here as authority and (nested) sovereignty (cf Simpson 2014).Footnote 35

Complementing articulations of Devendra authority through sensory saturation, the content of individual flexboards and cut-outs at the Niṉaivu Viḻā iconographically asserts the community's righteous heroism. Immanuvel, of course, appears with the most frequency. He is often depicted in his military uniform, although his time in the Indian National Army was short lived.

In such depictions, he appears standing up straight or marching towards the viewer in a military uniform fitted with the pins and medals of a well-decorated soldier. He demonstrates the pride and dignity of a man who has been honoured at the national level and who thus transcends the historical oppression to which his community has been subjected. As Chandrabose claims, Immanuvel ‘came back [from the army] wearing his new boots and sporting his new ideas of equality for all’ (Iyer Reference Iyer2016).

Even more frequently, Immanuvel is depicted in another guise that highlights his vīram as he challenges Thevar authority. He appears sitting with his legs crossed, clad in a pure white, Oxford-style shirt, white vēṣṭi, and leather sandals, which are typically worn by Tamil men in formal contexts and which have become something like a uniform for (male) Dravidian politicians.Footnote 36 Immanuvel extends his hand and points his index finger out towards the viewer, referring to the story of his conflict with Muthuramalingam during which he refused to see the Thevar leader as worthy of respect superior to his own. Some larger flexboards feature Immanuvel in both forms, emphasizing his dual heroism as regimented soldier and spirited fighter.

The mythico-historical spirit of Immanuvel is taken up by Devendra leaders who citationally embody his heroism in their promotional signs. For example, at the 2012 Niṉaivu Viḻā, three enormous, identical flexboard archways featuring the aspiring Devendra leader Suba Annamalai marked the beginning, middle, and end of the thoroughfare on which the parade took place (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Archway featuring Suba Annamalai at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: Author 2012.

Because he does not have a significant support base compared to someone like J. P. or Krishnasamy, Annamalai attempted to make his newly established party known through eye-catching archways that associated him with Immanuvel through proximity, mimetic postures, and sartorial choices.Footnote 37 A waving Annamalai appeared above a waving Immanuvel, a sitting Annamalai above a sitting Immanuvel, and a standing Annamalai above a standing Immanuvel. The archways’ bright red-and-green background referenced the hues’ widespread adoption as Devendra caste colours, which, I have been told many times, represent the red blood spilled in wars and the green of rice paddy (as per Devendras's claims to be heroic warriors and a cultivating, land-owning caste).Footnote 38

The archway also featured text describing the event through the eyes of Annamalai and his followers. Augmenting popular understandings of the function as a day of reverence and remembrance, the archway referred to the event as the ‘Mallar's Political Rising Day’, thus explicitly recognizing the political potential of Devendra collective identity generated by the event. Below the announcement, in smaller white font, was a reference to the murders of the previous year (which I will soon explain): ‘Please join us in honouring the vīram of the seven martyrs who gave their lives on the Martyr's Memorial Day’. Vīram and its maximal articulation as martyrdom prominently marked Devendra identity making in Paramakudi.

At the Niṉaivu Viḻā, Devendras construct collective identity through acts of remembering and celebrating mythico-history that bring soon-to-be Devendras physically and ideologically together. In addition to producing Durkheimian collective effervescence in moments of dancing and chanting, the Niṉaivu Viḻā plays a pedagogical role, ‘reminding’ Devendras of their proud past. Its success is rooted, in part, in the mediated diffusion of the tone and narrative content of the event through videos and images posted on social media, souvenirs (like mini Immanuvel prints, statues, and t-shirts), and stories shared by word of mouth, which allow Devendras to claim heroism and righteousness as their defining and thus unifying features.

Recognition and refusal: the vulnerability of Devendra authority

Devendras's claims are not, however easily accepted by wider (non-Devendra) audiences, especially Thevars whose resistance to Devendra power is articulated in violent attacks and, more subtly, in their own competing mythico-historical claims. The righteousness and honour, which Devendras assert through the Niṉaivu Viḻā, stand in explicit opposition to the claims that Thevars make during their celebration of Muthuramalingam's birth (and death) anniversary—Thevar Jayanthi (or Thevar Guru Puja).Footnote 39 Observed annually on 30 October in Muthuramalingam's native village of Pasumpon (Ramanathapuram District) and at one of the busiest intersections in the large city of Madurai (77 km northwest of Paramakudi),Footnote 40 the event attracts thousands of Thevars. They propitiate Muthuramalingam as a divine ancestor and Indian freedom fighter whose leadership strengthened their own community and the nation writ large.

As Thevars do not generally accept allegations that Muthuramalingam was responsible for Immanuvel's death, a reality that would conflict with his saintly status, both memorial events become spaces for competitive proclamations of righteousness. Even the fact that Devendras can honour their own caste hero in opposition to Muthuramalingam is itself an affront to Thevars’ insistence on their superior status. What is more, the temporal and physical proximity of the memorial events precipitates an annual resurrection of the two castes’ mutual animosity, making September and October particularly dangerous months in southern Tamil Nadu.

Despite contestation and conflict, the recognition that Thevar Jayanthi receives relative to the Niṉaivu Viḻā demonstrates that Thevar domination endures. Thevar Jayanthi rose to state-wide prominence about ten years before the Niṉaivu Viḻā, is celebrated on a much larger scale, and receives much more state support in the form of amenities like fresh water and emergency healthcare facilities. More importantly, leaders of Tamil Nadu's dominant political parties, the DMK and AIADMK, continue a long tradition of participation and legitimation that has policy implications beyond Thevar Jayanthi.Footnote 41 For example, by way of a 1985 government order, the AIADMK carved out a new district from Ramanathapuram District that it called Pasumpon Muthuramalinga Thevar District (Kumar Reference Kumar1991). A 1991 census handbook describes the district as ‘traditional Marava country’ and assures readers that it is ‘appropriate and apt to name a district in honour of this great son of India, Pasumpon Muthuramalinga Thevar’ (Kumar Reference Kumar1991, 10 and 12). While the burgeoning controversy over the new district, indexed by the handbook's defensiveness, resulted in its official erasure, Dravidian party recognition of Thevar honour continues.

In 2019, Chief Minister Palaniswami expressed the AIADMK's support by reminding reporters that the party declared Thevar Jayanthi an official function in 1979 and that former Chief Minister Jayalalithaa installed a bronze statue of Muthuramalingam in Chennai in 1996 and adorned the bust of Muthuramalingam in Pasumpon with a gold shield in 2014 (Scott Reference Scott2019).Footnote 42 Similarly, DMK president M. K. Stalin described Muthuramalingam as a freedom fighter and noted that ‘The DMK takes pride in paying homage to the great leader’ (Scott Reference Scott2019). As major political leaders garland the grave of Muthuramalingam during the widely televised official government function, there remains no doubt that the state recognizes Thevar dominance and bends to their will. Devendras, by contrast, fight for recognition of their righteous heroism, balancing defiance with respectful compliance.

Instead of receiving the recognition they seek, Devendras are sometimes repudiated with brutal violence.Footnote 43 One such moment was the 2011 Paramakudi police shooting. The details of the events that unfolded on 11 September 2011 are contested, as government sources and many media outlets maintain that police were defending themselves, while civil and human rights organizations, NGOs, and scholars claim that the police killed without much provocation (Parthasarathi Reference Parthasarathi2011, 15; Geetha Reference Geetha2011).Footnote 44 All parties have nonetheless agreed on the fact that police shot into a crowd of Devendra protesters, immediately killing five men.Footnote 45 Two more succumbed to their injuries in the local hospital.

In the days leading up to the shooting, Thevar–Devendra antagonism surged in the area. In and around Paramakudi Thevar groups allegedly tore down flexboards featuring Immanuvel. On 9 September, a 16-year-old boy by the name of Palanikumar, was murdered in Pallapacheri (a village about 50 kilometres from Paramakudi) by Thevars who falsely claimed that he had written ‘Muthuramalingam Thevar was a eunuch’ on a wall in the village. On 10 September, J. P. was arrested and detained in Pallapacheri where he had stopped on his way to the Niṉaivu Viḻā. In response, his supporters protested at Paramakudi's main junction outside the police station that was guarded by about 2,000 police officers, some of whom opened fire on the protesters (Parthasarathi Reference Parthasarathi2011, 15).

Chief Minister J. Jayalalithaa immediately responded to the murders in the Legislative Assembly. She claimed that the Paramakudi episode was the ‘culmination of a chain of events’ triggered by defamatory graffiti against Muthuramalinga Thevar. She did not denounce the police or refer to the long history of violence against Dalits in the area (Geetha Reference Geetha2011).

Such flagrant indifference fails to quash Devendras's desire for political recognition. Many of them are cynical of dominant parties, but they also desire and require state recognition, which has the potential to legitimate their mythico-historical narratives. At the 2012 Niṉaivu Viḻā, this tension was evident. AIADMK representatives were invited and participated, even as victims of the previous year's shootings were commemorated as heroic martyrs.

Small groups of cadres and (mostly local) leaders of major parties, inter alia the DMK, the North Indian Lok Janshakti Party (Folk People's Power Party), and the BJP also accepted invitations.Footnote 46 They paraded down the packed main road of Paramakudi with their banners and contributed to what became an enormous pile of garlands on the samadhi, bringing perumai—greatness—to the event. More importantly, the participation of powerful parties suggested, at least momentarily, the broad-based recognition of Devendra claims to authority.Footnote 47

Devendra authority cannot, however, be achieved without a struggle, as Dr Krishnasamy knows. During the 2012 Niṉaivu Viḻā, he arrived just after nightfall and was pushed up to the samadhi by his cadres, who had formed a protective barrier around him. He was handed a microphone, which he wielded to remind the crowd of the previous year's deep disappointments. Not only did the AIADMK fail to make 11 September a government recognized function (like Thevar Jayanthi), but they also failed to protect the Devendras from violence. In Krishnasamy's words, ‘after two years, they still have not done it. And last year, Devendra men were killed by the police. A [memorial] pillar should be erected for the martyrs.’ The crowd whistled and cheered in enthusiastic agreement, and Krishnasamy slipped away into the idling vehicle that was waiting for him. He had directly addressed Devendra desire for recognition by referring not only to the need to establish a government function, but also to construct a monument for the Devendra martyrs whose deaths had demonstrated the fragility of Devendra atikāram.

Arriving after Krishnasamy's departure, J. P. generated anxious anticipation that charged the crowd (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Crowd waits for J. P. at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: Author 2012.

After about an hour-and-a-half of waiting, the sound of approaching drumbeats and chants indicated J. P.'s arrival. As the words of the advancing entourage grew louder, the crowd in front of the samadhi joined in: ‘John Pandian—vāḻkkai Immanuvel Sekaran—vāḻkkai … Immanuvel Sekaranukku vīra vaṇakkam, vīra vaṇakkam, John Pandianukku vīra vaṇakkam …’, ‘Long live John Pandian, long live Immanuvel Sekaran, hail to the hero Immanuvel Sekaran, hail to the hero, hail to the hero John Pandian’.

A man of considerable height, J. P. was visible above the crowd, his face illuminated by the spotlights directed at the samadhi. His wife, Priscilla Pandian, bedecked in a shimmering silk sari and heavy gold jewellery for the occasion, accompanied him (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. J. P. and Priscilla Pandian at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: Author 2012.

The crowd erupted when J. P. approached the samadhi. A chorus of piercing whistles accompanied chants of ‘John Pandian—vaḷkka! John Pandian—vaḷkka!’, ‘Long live John Pandian! Long live John Pandian!’ Staring out into the crowd, J. P. performed añjali by raising his hands above his head and pressing his palms together (see Figure 9). He held this position of worship and salutation for several seconds, and the crowd's excitement soared.

Figure 9. J. P. performs añjali at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: Author 2012.

J. P. had honoured participants as if they too had made the ultimate sacrifice that they attribute to Immanuvel and to the seven men who had lost their lives the year prior.

J. P. then approached the banner featuring the pictures and names of the seven victims of the previous year's state violence. Across the top of the banner, bold font read vīra vaṇakkam (hail to the hero) (see Figure 10).

Figure 10. Victims of the previous year's police shooting at the Paramakudi Niṉaivu Viḻā in 2012. Source: Author 2012.

J. P. performed añjali before the fallen heroes and laid down garlands at the base of the banner as the crowd reached its deafening zenith, which continued as he swiftly departed.

The Niṉaivu Viḻā was over and quiet returned as participants slowly headed towards their homes. There was no closing speech, no formal goodbye, but instead a gentle fade-out that allowed the power of the event to endure. Participants were left with images of collective history characterized by vīram, honour, and authority, and, more importantly, their common cause with other Devendrakula Vellalars. While Devendras do not necessarily agree on the strategies or goals of their political battles, the fact that they are embattled brings them together.

Conclusion: Contestation, democracy, and collectivity

I have argued above that assertions of Devendra authority grounded in mythico-histories are complicated by their need for recognition by the array of communities now falling within the consolidated Devendrakula Vellalar caste and by those outside the Devendra fold. The former are oftentimes attracted to appealing histories that disavow their victimization, while some among the latter (that is, Thevars) are threatened by Devendra mythico-histories that belie their own. Others outside the Devendra fold, especially political actors, assert the supremacy of their authority by violently repudiating Devendra claims but also sometimes court Devendras in order to gain their support in the form of votes.

The process of collective identity making the Devendras undertake thus serves to give them political power. The larger and more united they are, the more parties and their machinations of governance must attend to them. It is not surprising then that mythico-historical claims are increasingly common among other castes in Tamil Nadu. Arunthathiyars (SC) rally behind the late eighteenth-century anti-British fighter Ondiveeran, and Thevars have added three mid to late eighteenth-century anti-British chieftains—Puli Thevar and the Maruthu Pandiyar brothers—to the repertoire of caste heroes they honour.Footnote 48 Beyond Tamil Nadu, the North Indian Yadavs (OBC), who have become a substantial political force in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, adopt similar strategies. Yadav caste organizations with national ambitions, Lucia Michelutti (Reference Michelutti2004) demonstrates, have succeeded in their erasure of older caste divisions and facilitated a broad-based consolidation, in part through the construction and dissemination of self-aggrandizing historical narratives. Many Yadavs now claim to be descendants of the god Krishna and thus primordially predisposed to ‘martial’ qualities and, at the same time, congenitally committed to ‘social justice’. As Michelutti's (Reference Michelutti2004, 46) interlocutors put it, Yadavs are ‘born to be politicians’ in democratic India.

The Devendras are thus one among many examples of caste-based mobilization that can help us understand political life in contemporary India, one of the most heavily politicized countries in the world, as evidenced by consistently high rates of voter turnout (Spencer Reference Spencer and Banerjee2014, xvii–xix in Banerjee Reference Banerjee2014)Footnote 49 and by the dizzying proliferation of political parties that intersect with and sometimes produce caste and religious identities. As Thomas Blom Hansen recalls, there is a ‘certain irrepressible quality … [of] political life in India’ characterized by ‘incessant recoding … and reevaluation of virtually every identity’ (Hansen Reference Hansen1999, 58–59). Entanglements of personal and political identities are not, however, perversions of contemporary democracy or holdovers from earlier times. To again quote Hansen, democracy lives not just in formal institutions of governance, but in the ‘questioning and subversion of social hierarchies and certitudes that over time produce an altogether different society’ (Hansen Reference Hansen1999, 18).Footnote 50

The Devendras's attempts to effect sociopolitical change that I have examined in this article demonstrate that those engaged in the questioning and subversion to which Hansen refers face an onerous task without end. They must construct a collective self with the power to overcome differences internal to their aspirational collectivity, which are increasing with economic diversification and urbanization. At the same time, they contend with both the competing claims of other groups and the authority of the state to grant them the status of official recognition. The Devendras's claims to rights structuring opportunities that Mosse (Reference Mosse2012) identifies in contemporary caste-based political mobilization thus include the rights to honour and respectability, values that he locates in an earlier historical moment of caste practices and ideologies. Ultimately, the symbolic and material dimensions of authority undergirding political power are both inextricably linked and irreducible to each other for the Devendras and other communities developing in a world characterized by rapid and profound transformation and perpetual contestation.

Competing interests

None.