In these few contradictions you have the whole Czechoslovakia. It is a country old yet new. Great yet small. Highly civilized yet very simple. It is beautiful. But there are possibly places more so. It is rich. But there are wealthier lands. It has a high level of culture. But there are states with higher. Still, there is perhaps no country which displays such vital determination and capacity as this small nation, which has held its own and will hold its own in Central Europe.

– Čapek [Reference Čapek1936] 1991, 451

This inscription by Karel Čapek (1890–1938), the Czech novelist, journalist and playwright, formed a prominent part of the installation inside the Czechoslovak pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. The quotation was originally published in 1936 as part of a text that served as an introduction to the new journal Srdce Evropy (The Heart of Europe) (Pynsent Reference Pynsent2013, 11), a popularizing publication that also had a French language version for international audiences. Here, Čapek described Czechoslovakia as the economic, geological, and geographical crossroads of Europe as well as “an island of democracy” with proud inhabitants who fought in great wars, preserved their language, and eventually reached independence despite all the hardships imposed on them from the outside (Čapek Reference Čapek1936, 450). This patriotic description of the country was his personal response to the increasing threats to Czechoslovak independence in the 1930s.

In the New York World’s Fair, organized under the motto “World of Tomorrow,” the extract appeared underneath a symbolic depiction of Czechoslovakia, a collage with “typical” cultural phenomena of the entire country, extending from the western border with Germany to the eastern regions of the Subcarpathean Ruthenia, which became part of the country after the First World War. Juxtaposed with this representation, Čapek’s quotation evoked a romantic image of a humble yet determined nation that was both civilized and simple. Such narratives had strong roots and dated back to 19th century national revival historians, such as author of the influential multivolume Czech history, František Palacký (1798–1876).Footnote 1 The large collage, which consisted of a wood carving, paint, and fragments of various materials, was designed by the artists and professors of the School of Decorative Arts in Prague, Antonín Strnadel and Josef Novák. They represented the westernmost regions through an inhabitant of Chodsko, clad in a heavy coat – the Chods were the historic protectors of the borders with Germany. A group of Sokol gymnasts followed, while Prague was represented by the castle, with a middle-class gentleman reading a newspaper and a lady in her Sunday best. Half-way through the collage, more rural scenes appeared, with the Carpathian Mountains and the regions of eastern Moravia and Slovakia. These were symbolized by peasants either attending animals or engaged in dancing or playing an instrument. The easternmost region of Subcarpathean Ruthenia was then depicted as a land of forests where timber was harvested. Both the collage and the accompanying text in New York thus simplified what was deemed characteristic of Czechoslovakia and its different parts and regions: the Bohemian west of the state was urbanized, industrialized, and cultured, while the Slovak and Ruthenian east were more rural, agricultural, and primitive. To appeal to audiences mostly unfamiliar with the state, its nation, and their location, the message about Czechoslovakia’s key features had to be abbreviated. In the New York fair as well as in other international contexts, it was therefore showcased as a future-oriented, progressive, and democratic country which, nevertheless, retained prominent and traditional folk culture ("Czechoslovak Pavilion”). This dichotomy, identical with the west-east divide, became crucial in all international presentations of the state.

Putting aside the fact that the New York World’s Fair took place under very specific political circumstances, when Czechoslovakia no longer existed, the way the organizers framed the country’s national profile was the same as in earlier fairs of the interwar period. In this way, Czechoslovakia did not differ from other countries that presented a carefully constructed image of themselves in international exhibitions and world’s fairs. It was usually national governments that put up national pavilions at international exhibitions, and what they displayed within was closely linked to the respective state’s vision of itself and their nation. However, this practice, especially in the case of the Central European states that were created in 1918, invites the question: what and who was the nation? For these newly formed states, born out of the First World War and the fall of the Habsburg Monarchy, world’s fairs presented an excellent opportunity to negotiate their place on the international political and cultural forum. Czechoslovakia was no exception, yet its situation was also rather different when compared to, for instance, the newly formed Austria and Hungary. In an attempt to disassociate themselves from the Habsburg past, politicians and historians of interwar Czechoslovakia liked to present the state as one of the winners of the First World War, or at least not one of the losers, emphasising, for instance, the role of the Czechoslovak Legion in the conflict. On the other hand, the state inherited various legacies from the Monarchy that influenced, among other things, the content and ideology of its displays at world’s fairs.

Taking these circumstances into consideration, this article focuses on the narratives and ideas of the state and nation that were put forward at Czechoslovak presentations at international exhibitions and world’s fairs.Footnote 2 The contradictions identified by Čapek described a humble, yet determined state that strove to display an image of a single nation. This nation, however, was also full of internal contradictions, partly visualized in the shorthand representation of a diverse country with a distinctive west-east cultural and social divide. The Bohemian region was linked more closely to the outcomes of modernity, including the bourgeois culture, sports, and the arts, while Slovakia and Ruthenia were more often portrayed as pre-industrial and pre-modern in their attachment to traditional culture and crafts.

Using examples from a selection of world’s fairs with a Czechoslovak presence, I explore the deliberate contrasts that were created between the modern and traditional aspects of the new Czechoslovak nation and the ways in which the various ethnic groups of Czechoslovakia were included. I therefore question the attempt to project a notion of a single Czechoslovak nation through exhibitions, and ask what kind of a nation the organizers representing Czechoslovakia in New York and in other world’s fairs imagined, and how successful these projections were.

What was Czechoslovakia: Building an Identity

From their early days in the 1840s and 1850s, international exhibitions developed into complex events with the participation of many countries from around the world. Their increasing size, as well as the need to distinguish between various national economies and cultures, led to the division of exhibition grounds into national pavilions, which first took place at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867. The distribution of nations into separate buildings or sections instilled order at the exhibition ground and was adopted by most later fairs (Mainardi Reference Mainardi1987). Clear national differentiation became particularly important at specific moments of time linked to political rupture, such as the redrawing of state frontiers after world wars or the dissolution of empires. Soon after Czechoslovakia was formed in 1918 out of the collapsing Habsburg monarchy, it started using world’s fairs to project, and to an extent consolidate, its image of both a state and a nation to the rest of the world.

The participation of Czechoslovakia as a single entity in international exhibitions was a novelty for the territory that was part of Austria-Hungary until 1918. After the Dual monarchy was created in 1867, the Czech lands (the territory of Bohemia, Moravia, and part of Silesia) were governed from Vienna, while Slovakia and Subcarpathian Ruthenia fell under the Hungarian administration. Their presence at international exhibitions was therefore very much subjected to this political division. Austria, or Cisleithania, and Hungary, or Transleithania, were both participants at exhibitions abroad and at the large domestic exhibition, the Weltausstellung in Vienna in 1873. This event became an immense display of science and industry, which was aimed at showing the Habsburg monarchy as a great political and economic power (Pemsel Reference Pemsel1989; Rampley Reference Rampley2011; Wörner Reference Wörner1999). The two parts of the Dual Monarchy also appeared separately at various world’s fairs – for instance Hungary was represented at Paris in 1900 and in St Louis in 1904. In Paris in 1900, Austria also built a Bosnia and Hercegovina pavilion for a region, which recently fell under its administration following the Habsburg occupation in 1878, and both Austria and Hungary contributed to the Panama Pacific exposition in 1915.

As regards the Czech speaking lands, they had very few separate representations and exhibits at international fairs before 1918. Objects labelled as Bohemian could be spotted at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, the Paris expositions universelles, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904, and even as far as Launceston, Tasmania, where a Bohemian section formed part of the International Exhibition in 1891–92. Yet what was termed Bohemian at these occasions related to a geographical region rather than to a specific national group. Representatives of Czech businesses, institutions, and societies also made their mark at the Vienna World’s Fair not by their presence, but by their absence. They refused to take official part in the event because they were denied their own exhibition space and saw the entire World’s Fair as too Germanic (Hallwich Reference Hallwich1873, 1–2). Companies and producers from Slovakia took part in the Weltausstellung as part of the Hungarian entries which presented this part of the Dual Monarchy as predominantly agricultural and artisan (Komora Reference Komora2017, 43).

As an independent state, Czechoslovakia took to the international world’s fairs stage quickly and used its active presence as an opportunity to legitimize itself. Unlike any other successor state of the Habsburg Empire, Czechoslovakia participated in all major interwar world’s fairs and international exhibitions between 1920 and 1940; this was around twenty events in Europe, North and South America, and New Zealand. They included the exhibitions in Rio de Janeiro in 1922, Paris in 1925, and Chicago in 1933, which I discuss in more detail together with the aforementioned New York World’s Fair of 1939. Other important Czechoslovak entries were for the exhibitions in Philadelphia, 1926; Barcelona, 1929; Brussels, 1935; and Paris, 1937. The presentations shared a desire to showcase Czechoslovakia as politically independent and economically self-sufficient, yet historically and culturally legitimized. And although the exhibition strategies developed during the interwar period moved towards more elaborate and coherent concepts and designs, especially of the interior and its layout, the overall display reiterated the same narrative.

First of all, Czechoslovakia tried to present itself as a single nation-state, a home of the single Czechoslovak nation, even though it consisted of quite a large number of national groups and was, in fact, a multinational state. Such a strategy raises the question about what definitions of state and nation were employed and, more specifically, who constructed the Czechoslovak state and nation and how. Along with Rogers Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1996, 5), I argue that Czechoslovakia was a nationalising state, whose core was created of Czechs and Slovaks as the “legitimate owners” of the state and a Slavonic majority. Shortly after the end of the First World War, this core was, nevertheless, still in a weak cultural, economic, and demographic position, and the state therefore had to strengthen it internally and externally. International exhibitions presented a great opportunity for such strengthening; the Czechoslovak pavilion was constructed as nationalizing, rather than national.

In order to consolidate a uniform impression of Czechoslovakia, the government promoted the political programme of Czechoslovakism, which emphasized – and to a large extent invented – joint historic roots of Czechs and Slovaks. The idea of a Czechoslovak nation and people was devised already during the war as another nationalizing practice, “the conscious strategy of Czech and Slovak diplomats in their effort not to confuse the politicians of the Alliance, who were expected to be unfamiliar with the history and ethnic composition of Central Europe” (Holý Reference Holý1996, 95). It gave historical backing to their cohabitation in one state after 1918, and created a Slavic majority against a substantial population of Germans and Hungarians. Apart from a shared culture, scholars and politicians advocating Czechoslovakism argued for the similarity of the languages and they also identified shared historical moments in Czech and Slovak history and culture. They understood them as a justification for the joint state of Czechoslovakia. These included the shared political existence in the 9th century Great Moravian Empire, or material and visual similarities of the folk culture in south-east Moravia and Slovakia. This was one of the reasons why folk art and craft of the people in the countryside and villages was granted an important place within exhibitions and played a key role in the construction of Czechoslovakism, which I will come back to in more detail shortly.

While references to various aspects of Czechoslovakism in the Czechoslovak pavilions were frequent, no consistent definition of any nation, whether Czechoslovak, Czech, or Slovak existed (Ducháček Reference Ducháček, Kopeček, Mervart and Hudek2019, 158). It was only the Czechoslovak language that the Constitution of 1920 codified when it included a section on national, religious and ethnic minorities, securing their rights (“Language Law”). The Czechoslovak nation was therefore for many people a natural and historic phenomenon. At the same time, the concept stood on the Czech idea of a self-determined nation, conceived as a Czech nation, which predated the vision of creating an independent state. The ultimate decision for a joint Czechoslovak state was a solution to the realisation of the limited size of each individual group that sought autonomy or independence from the Habsburg Monarchy. As a consequence, the lack of a commonly accepted definition of the Czechoslovak nation had a direct consequence in the limited way the Czechoslovak displays were constructed.

The Nation as an Exhibit

While there was no unambiguous definition of the Czechoslovak nation, several tropes were established and displayed as typical of it. One of the most visible ones was the modernity of the state and the historicity of the nation. While the former could be easily identified with industries, trade, high culture, and education – as in the collage from New York – the latter related to medieval heritage as well as folk art and culture. It was especially folk art that played a significant homogenizing role in the construction of a common culture and history of interwar Czechoslovakia; exhibition organizers identified similarities in the visual and ritual practices of the countryside in the Czech and Slovak speaking regions, and used them as a proof of the existence of shared historic and Slavic culture that survived the administrative and political separation in Austria-Hungary.

This strategy was adopted at the first substantial appearance of Czechoslovakia in the interwar period. The Centenary Exhibition in Rio de Janeiro, Commemoraçao do centenario da independencia do Brasil International Exposition, took place in 1922 with only 13 states from abroad and celebrated the anniversary of Brazil’s independence. It was an opportunity for the Brazilian organizer to use the exhibition for promoting the republican government, economic recovery, and future trade, in other words as a vehicle to display the state’s modernity (Rezende Reference Rezende and Filipová2015). Czechoslovakia showcased here its products for reasons that the government officially advertised as purely economic. These benefits, however, were accompanied by a more political motivated intention of the government to put the new state of Czechoslovakia on the political world map through the participation in this type of international contest. Ladislav Turnovský, the governmental commissioner general for the exhibition, emphasized that Czechoslovakia was the “only state from the entire Central Europe,” and had a place next to a limited number of foreign exhibits of, for example, the United States, Japan, Portugal, Great Britain, and France (Turnovský Reference Turnovský1923, 2).Footnote 3

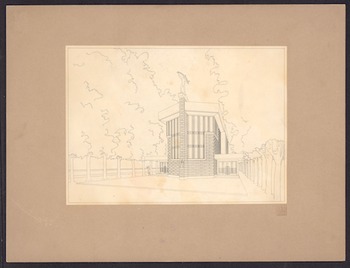

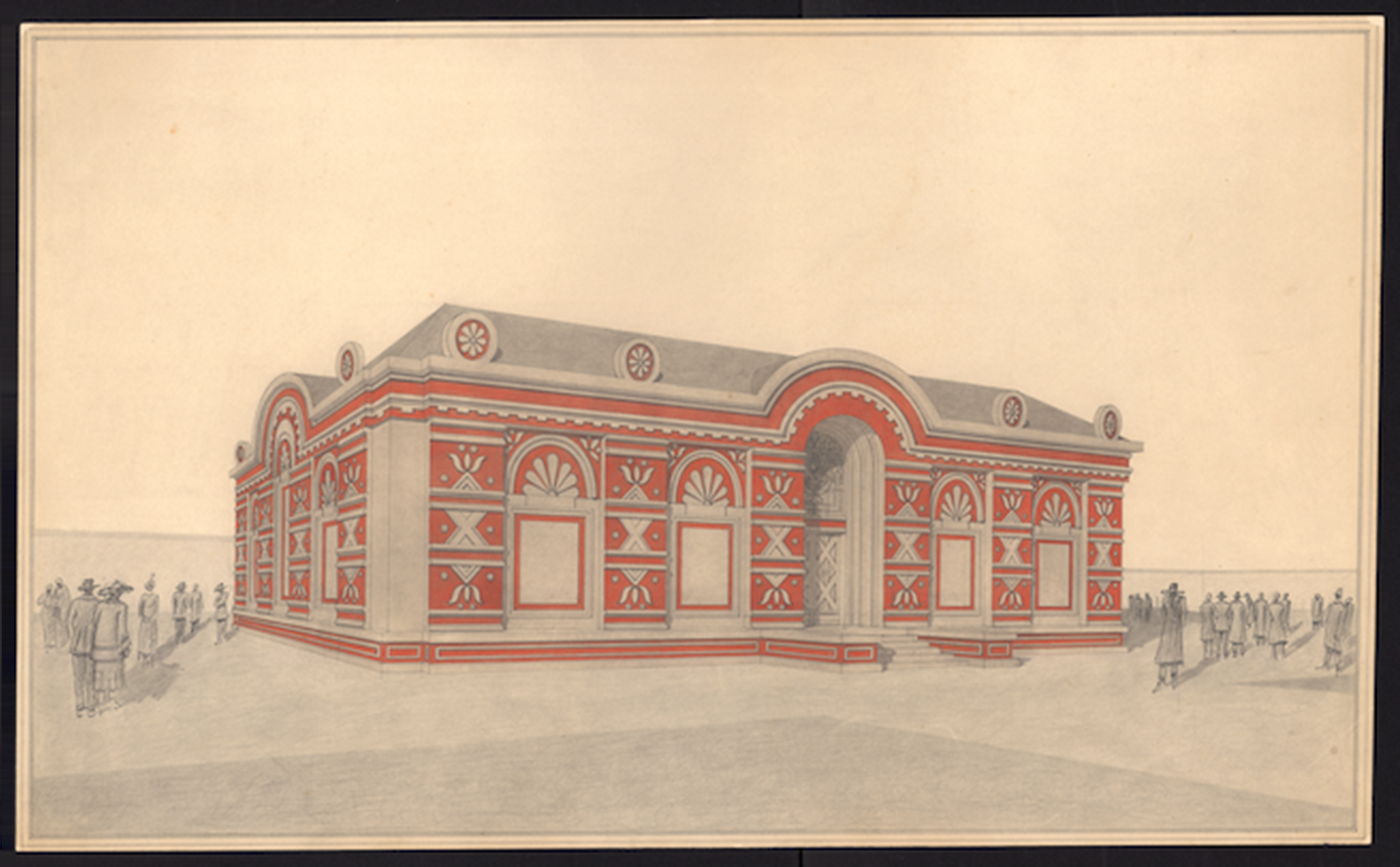

The Czechoslovak pavilion at Rio de Janeiro was set to display modernization of the state which was evident in, for example, expansion to new markets of the Americas and the conscious creation of political alliances with the western powers – especially France, USA, and Great Britain. Designed by the Czech architects Pavel Janák and Josef Pytlík, the Czechoslovak pavilion made distinctive references to folk culture, with motives derived from for example floral ornaments and bright colouring used in folk decoration in villages across Czechoslovakia (figure 1). This seeming contradiction between the modern and the traditional was an important component of the more general search for the new visual identity of the state. Following the end of the war, many architects and designers were aware of the need to find an appropriate visual language with which to express the new political situation and serve the new state and people. Janák was one of the key architects who experimented with references to local folk traditions which for him could inform the new visual identity of the state. The architecture of the Czechoslovak pavilion in Rio, as the commemorative book of the exhibition remarked, was the expression of “a modern artistic current characterized by the attempt to break free from the old classical models by introducing elements of national culture” (Lévy Reference Lévy2010, 231). This culture was that of the peasants whose linear motifs from embroidery were effectively translated into the building’s ornamental decoration and presented as part of the modern artistic expression.

Figure 1. Pavel Janák, Czechoslovak pavilion in Rio, 1922, National Technical Museum Prague, Museum of Architecture and Engineering, fond 85 Janák.

Little information of what exactly the interior contained can be found but the ground plan shows that the space consisted of one great hall divided by tables, cabinets, and partitions. One of the main features was a stained-glass window designed by František Kysela, an artist and lecturer at the School of Art and Design in Prague, containing the Czechoslovak emblem. Around 80 companies exhibited here mainly products of the glass industry and agricultural machinery (‘Čs. pavilon’ 1922, 9). Other displays were of ceramics and furniture of various companies, hops, pencils, and carpets, all items suitable for future export (Turnovský Reference Turnovský1923, 6).

Most of the Czechoslovak presentations in the interwar fairs shared similar features designed to send out a uniform message about the new state and its modernity (figure 2). This was partly due to the organization process which was established over the course of the interwar period. A committee consisting of representatives of various ministries (especially that of trade, foreign affairs, education, and public works), together with trade organizations and cultural institutions, such as museums and specialized schools, would publish a call for the architecture of the pavilion, its internal layout, and individual sections (“Nástin” 1–9). Often, though, they also directly approached specific architects or companies and invited them to participate. As a result, large firms, like the Škoda motors or the Pilsner brewery, appeared regularly in the pavilions. As the different ministries promoted different goals, their discussions about the main emphasis of the official presentation were frequent. For instance, the ministry of trade that emphasized the business element of the exhibitions frequently disputed the views of the ministry of public works which, among others, promoted the educational, cultural, and artistic factors of the exhibits (“Zpráva” 2).

Figure 2. View of the exhibition space in the Czechoslovak pavilion, Brussels International Exposition, 1935, Moravian Regional Archive in Brno, State District Archive Zlín, Fond Baťa, a. s., Zlín, sign. XV, inv. no. 165, author unknown, 1935.

Generally, though, the official requirements for all exhibition designs called for a unified look, attractiveness of the display, and its economy (“Nástin” 1927, 2–3). Visitors were not supposed to be overburdened with too much factual information and instead they needed to be entertained by interesting objects as exhibition fatigue was a known problem. Architects and designers should also consider economical use of the exhibition space as well as the amount of possible time visitors could spend in the exhibit (“Nástin” 1927, 3). Soon in the short interwar exhibition history, the internal design started taking the visitor around the pavilion on a planned one-way route through various sections of the display, rather than presenting the material in individual rooms or one big gallery as in Rio.

The Czechoslovak pavilions also routinely comprised a large entrance hall with a centrally placed bust of the President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937) and Rio de Janeiro was no exception. Made of bronze by the Czech sculptor Jan Štursa (1880–1925), the bust was reproduced from a marble original that was placed in the parliament in Prague. Copies were cast for various Czechoslovak pavilions in the interwar period as well as for many locations across Czechoslovakia. Although Masaryk as a president was not directly involved in the Czechoslovak exhibitions, it is clear from the amount of archival documentation of the Presidential Office that he was aware of the organization process and the eventual successes of the exhibits. Masaryk’s symbolic presence through a prominently placed sculpture in the Czechoslovak pavilions or sections was quite crucial. His role of a representative of the state abroad accompanied the image of the president as the country’s protector. Such a narrative, however, was not dissimilar to that given to Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph (1830–1916), the “bright, fatherly and kind head of state,” as he was described at the Jubilee Exhibition in Prague in 1891 (Kronbauer Reference Kronbauer1892, 279). In this and other exhibitions, organized prior to 1918, the emperor’s statues were situated in prominent places. And like Franz Joseph, Masaryk was also regularly referred to as caring, charitable, and modest, which was an image of the head of the state that survived from the monarchy (Rak Reference Rak and Řepa2008, 267).

The main exhibition space would also state symbols such as flags, emblems, and often “a large map of Europe with Czechoslovakia marked out and with the main train, water and flight routes” to indicate where and how well connected the country was (“Nástin” 1927, 3). The industrial section would include products such as turbines, aeroplane and car parts, and presentations of companies and businesses, such as breweries, steelworks, chemistry, textiles, or agriculture. Displays promoting tourism and showcasing the country’s history and the present through photographs, paintings, and statistical information had an important place. Each pavilion, or dedicated national section, also featured a selection of works of folk art as well as modern art, design objects such as furniture, textiles, glass, or kitchen utensils. Based on the location of the world’s fair, a part representing the local Czech and Slovak diaspora would also be included. The important role of the Czechoslovak restaurant, a common addition to the pavilion, where hostesses in national costumes offered local food and Pilsner beer, should also be mentioned.

A careful presentation of the country’s historicity and traditions, which was partly executed through the visual arts and especially the embrace of folk art, accompanied the vision of the new democratic and modern state. This, however, was not a novelty. For a long time, many artists, historians, and others considered folk culture across Central Europe as an important element in the recovery of the nations and their identity. Ethnographers, anthropologists, and art historians collected and described its elements, including material objects, costumes, songs, tales, and customs from the early nineteenth century onwards as a part of the search for the national roots. This became a political programme of the Czech intelligentsia in Bohemia of the 19th century too, and folk culture was framed with an ideological agenda. Whereas high culture had been for a long time claimed by the middle-class Bohemian Germans, a practice disputed by Czechs, the latter also started to study the “low culture” of the villages as associated with genuine “Czechness.” Similar politics translated into a number of late 19th century exhibitions that were organized in Prague. Both at the industrial Jubilee Exhibition of 1891 and the Czechoslavic Ethnographic Exhibition in 1895, the peasants of the Czech speaking lands became the “repository of identity and seat of patriotism” (Sayer Reference Sayer1998 119; Albrecht Reference Albrecht1993). One of the key goals of the organizers of both events was to present Czech national culture as traditional and historic, free from influences of other ethnic groups in the Czech speaking lands, especially Germans (Filipová Reference Filipová2011). Through the exhibits of peasantry, their visual and material culture, the two Prague exhibitions stressed the important role of local folk culture for present and future development of a modern Czech nation.

The pavilion in Rio was the only one where the architecture explicitly quoted elements of Central European folk architecture. Architects of subsequent Czechoslovak pavilions opted for less decorative designs. The Rio pavilion, however, indicated that vernacular, or folk, art had a continuously important place in Czechoslovak pavilions and a distinctive ideological role. Yet the emphasis of the late 19th century expositions on ethnographic location of the peasant people in the forming nation lost its topicality in the face of embracing modernity. In the interwar period, folk culture was given two additional roles which are obvious in the way it was included in the world’s fairs. One role was decorative, and folk art and crafts as presented in exhibitions were aestheticized for public consumption. The second role was more political; folk culture as displayed abroad became a marker of both unity and difference, be it ethnic, social, economic, cultural or geographical, and in all of these forms it contributed to the formation of the idea of the Czechoslovak state.

Unity in Difference. The Place of Slovakia in Czechoslovak Pavilions

There is no Slovak nation, that’s an invention of Hungarian propaganda.

– Masaryk Reference Masaryk1921, 78

The political role of folk art could be seen especially in its close association with the rural Slovak regions and with the way Slovakia was framed in the exhibitions. Within the narrative of a single Czechoslovak nation, folk culture retained its significance as one of the proofs that the Slavic groups, especially the Czechs and Slovaks, of Czechoslovakia shared many cultural and visual traditions despite their separation in the Habsburg monarchy. At the same time, however, the social and economic differences between the two main ethnic groups were identified and displayed, consciously or unconsciously, to indicate what was considered as different levels of “maturity” between them.

The narrative of uneven economic development of the west-east trajectory within Czechoslovakia was not limited to international exhibitions – Czech historians, art historians, journalists, and politicians after 1918 – and even before – often succumbed to such simplified views of the country to explain what they saw as different levels of economic and social standing. In the Habsburg Monarchy, Slovakia had been administered by Hungary and according to Slovak revivalists often neglected as a rural backwater. The Czech lands, however, under Austrian administration, were the most economically and industrially advanced part of the Empire. This helped to give rise to the narrative of the social and economic divide between the two parts – the Czech lands were often seen as more educated and middle class, whereas Slovakia was seen as underdeveloped and more rural. The collage in the Czechoslovak pavilion in New York, discussed at the beginning, is a great example of such simplified vision. Here, Ruthenia, a region in the easternmost part of Czechoslovakia that was part of the state in the interwar period, was almost nonexistent and was reduced to a mountainous land full of forests. As the most remote province from Prague’s point of view, it was often forgotten by Czechoslovak politicians or at best exoticized as a land to which they can deliver democracy, culture and order (Holubec Reference Holubec, Borodziej, Holubec and von Puttkamer2014, 223–250).

Apart from the Ruthenians, the many minorities of the state, the Hungarians, Poles, and Jews, hardly featured in the Czechoslovak displays. Germans enjoyed some presence through various trading organizations and businesses that participated in the pavilions, to which I will come back later. Yet the two largest groups of Czechs and Slovaks were also represented unequally, which, after all, reflected the general political, cultural, and artistic predominance of the Czechs within the state and its political and cultural life. First of all, the various exhibition committees, responsible for organization, design, and selection of objects, were based in Prague and consisted mostly of Czechs. Proportionately, representation of Slovakia usually amounted to less than 10% of the entire display, sometimes to as little as 4% (Komora Reference Komora2017, 233). This striking incongruity was the case of for instance the Exposition International des Arts et des Techniques in Paris in 1937, where the Czechoslovak (or rather Czech) pavilion was designed by the architects and designers Jaromír Krejcar, Zdeněk Kejř, Ladislav Sutnar, and Bohuslav Soumar in glass and steel. Here, as well as in the Exposition thematic pavilions, where Czechoslovakia was present, like in the fine arts, press, propaganda, and the international pavilion, Slovakia had a marginal role. Critics in Slovak newspapers noticed this and suggested sarcastically that the pavilion should be renamed the pavilion of Vítkovice steelworks, Škoda motors, and Jablonec bijou after the Czech companies that dominated the display (“Koho” 1937, 5). They also pointed to the fact that the symbolic, political, and historic representation was limited to Czechs; the entrance hall featured a sculpture of Masaryk, the historian Palacký, the scientist Jan Evangelista Purkyně, and the composer Bedřich Smetana, neglecting especially Milan Rastislav Štefánik, a politician born in Slovakia, who was one of the founders of the Czechoslovak state (“Koho” 1937, 5), served as a general in the French army, and was killed in a plane crash in 1919.

Yet, the organizers of various pavilions were indeed aware of the need to include Slovakia in some way and found folk art and culture as an excellent tool. Czechoslovakia took part in an earlier exhibition in Paris, the 1925 Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes. This exhibition was – as the name suggests – focused on art and design rather than purely on economy and trade, even though there was an undeniable commercial benefit sought by the organizers and exhibitors. In terms of the exhibition politics, it was motivated by France’s ambitions in the postwar years to promote French taste and luxury goods. The French organizers aimed to showcase a new style that became known as Art Deco. Yet it was here that an almost exact opposite to Art Deco, the French architect Le Corbusier’s functionalist model house l’Esprit Nouveau, put emphasis on the function of buildings and denounced decoration. The abstract, geometric structure was deemed incompatible with the overall concept of the exposition (Kostova Reference Kostova2011, 145) and a twenty-foot-high fence was temporarily put up around it. Furthermore, to separate decorative modernism from the more avant-garde art and design at the exhibition ground, Fernand Leger and Robert Delaunay’s paintings were removed from the Ambassade Francaise show and there was no display of the Bauhaus or De Stijl here (Mattie Reference Mattie1998, 141). With many other artists, Leger and Delaunay appeared in the protest exhibition “L’Art d’Aujourd’hui. Exposition des Arts plastiques non imitatifs” in Paris (Pravdová Reference Pravdová and Rousová2007, 69). To add to the discussion, Le Corbusier wrote a critique of the decorative art which he deemed excessive to people’s needs, and decoration was for him used to disguise poor manufacture (Greenhalgh Reference Greenhalgh1998, 15–16). The exhibition grounds therefore became a place of various competing views of the place of decoration and decorative arts in the modern world.

There was also a visible incongruousness between the exterior and interior of various pavilions. The Austrian pavilion, for instance, designed by Josef Hoffmann, was a compact concrete building with both the exterior and interior decorated in “exuberant floral- and folk-derived calligraphy” (Buenger Reference Buenger and Skrypzak2003, 13). The heavy decorations were criticized by the architect Adolf Loos, who saw them as a symptom of Vienna’s conservativism bordering on kitsch (Buenger Reference Buenger and Skrypzak2003, 12). The Czechoslovak pavilion was not much different. The Czech architect Josef Gočár devised it as a building in reinforced concrete and red tinted glass on a pentagonal ground plan (figure 3). Yet the French press described the interior as hefty and tasteless for its dark wooden panelling located all around the main hall and for the heavy furniture, designed by the Rio pavilion architect, Pavel Janák, displayed on the first floor (Benš Reference Benš1925, 18). In this case, Czechoslovakia was still looking for an appropriate image which would present its art and design as both modern and traditional.

Figure 3. Josef Gočár, Czechoslovak pavilion, Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925. National Technical Museum Prague, Museum of Architecture and Engineering, fond 14 Gočár, item 118, photograph by Štenc Prague.

The Czechoslovak entry was put together by representatives of the Czechoslovak government, the Czechoslovak embassy in Paris, art and design schools and museums in Prague, and members of the chamber of commerce from the largest cities, and was spread out through a number of locations. The national pavilion was the focal point, and its main hall featured the habitual bust of President Masaryk as well as stained glass, photographs of contemporary architecture, and tapestries by Kysela depicting various traditional craftsmen and trades (figure 4). The adjacent rooms contained cabinets with glass, sculptures, paintings, books, metal works, pottery, marionettes, and stage designs. There was also an exposition of the School of Decorative Arts from Prague in the Hall of Honour and a Czechoslovak section in the Grand Palais contained a mixture of historical and contemporary objects, such as Moser glass, Thonet furniture, toys, and embroideries, as well as presentations of design and craft schools. And even though both Moser and Thonet were companies founded in the 19th century by Bohemian German-speaking Jews and Germans respectively, their design products were now successfully incorporated in the Czechoslovak display as an evidence of the nation’s creative production (Filipová Reference Filipová, Fallan and Lees-Maffei2016). Thonet, for instance, previously represented Austria at international fairs, such as at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 or the Vienna Weltausstellung in 1873 (Rampley Reference Rampley, Matthew, Markian and Nóra2020, 160). Now that the companies were located in Czechoslovakia, they became part and parcel of the Czechoslovak national presentation. The German legacy in this case was not acknowledged and in general, there were only few instances where there was a reference to the German minority in the Czechoslovak pavilion in 1925. One important exception was the industrial schools section, which featured for instance glass making schools from the northern and western Bohemian border regions (Exposition 1925). These regions had traditionally a large number of glassworks founded and owned by Germans, with which the schools were associated (Filipová Reference Filipová, Fallan and Lees-Maffei2016).

Figure 4. Josef Gočár, interior of the Czechoslovak pavilion, Paris 1925. National Technical Museum Prague, Museum of Architecture and Engineering, fond 14 Gočár, item 118.

A more conscious effort was made to include Slovakia. It had a small place in the Hall of Honour in the selection of a handful of Slovak companies that produced craft objects based on folk art. Namely, it was the Bratislava-based institute called Detva, established “for elevating folk art and the home industries in Slovakia,” a society for helping folk industries Lipa from Martin in central Slovakia, and the Slovak Ceramics from Modra, near Bratislava, that displayed their embroidery, lace, textiles, and pottery (Komora Reference Komora2017, 204).

How to include Slovakia was a concern for the organizers who, nevertheless, produced a limited picture of the eastern region. Prior to the exposition, one of the most prominent members of the Paris and other exhibitions committees, the Czech art historian Václav Vilém Štech who worked at the Ministry of Education and National Enlightenment, concluded that “there is only one way Slovakia and Slovak politics can be represented at a world’s fair and it is through folk art” (Komora Reference Komora2017, 204). In this and all other interwar exhibitions, Slovakia was reduced to folk art displays in line with the general view of the region as predominantly rural, economically backward, and culturally underdeveloped. Štech also expressed a political-economic complaint about this fact, noting that “Slovaks will not contribute [financially] towards the exhibition but will expect to be represented by their works. Slovak art shall not be omitted if for nothing else but the domestic politics” (Komora Reference Komora2017, 204). The Prague-based authorities – or in other words, the dominant political and cultural elites, as Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1995, 130) calls them – actively nationalized the Czechoslovak displays while recognizing an existing tension between the two ethnic parts of the binational Czechoslovakia. Within the context of world’s fairs and international exhibitions, there were many examples of such an approach to Slovakia which could be seen as driven by two motives: the continued legacy of Austria-Hungary and the lack of a shared understanding of what the state and nation meant.

Both of these motives deserve a more detailed discussion in order to understand how and why Slovakia was portrayed in such a way. First of all, interwar Czechoslovakia inherited and continued many political practices and strategies from Austria-Hungary. Apart from the previously mentioned ethnic diversity, various bureaucratical processes and many Austrian laws were retained in the Czechoslovak system until the early 1930s (Orzoff Reference Orzoff2009, 129; Vlnas Reference Vlnas1991; Pynsent Reference Pynsent1994; Morelon Reference Morelon, Miller and Morelon2019). The creation of the new state, therefore, never was and never could have been a clear break from the old order. The political authorities, based in Prague and consisting predominantly of Czechs, saw the Slovak regions and Slovaks as in need of protection by a stronger power. Various individuals – mostly Czech writers, historians, and politicians, but some Slovaks too – applied this rhetoric to help explain the Czechoslovak union. One of the greatest defenders of Czechoslovakism, the teacher and writer Karel Kálal (1860–1930), promoted the Czechoslovak unity and the need to “protect Slovakia” from the early 20th century (Reference Kálal1906). He published a number of treatises and lectures about the history of Slovakia and the Czech presence on the territory and claimed that the Czechs saved the Slovaks from the Hungarians who had tried to exterminate them (Reference Kálal1918, 43). “Who has a better claim for a cohabitation with them? Who has the bounden duty to take care of them?” he asked in a way that suggested a paternalistic as well as colonial view of the Slovak region (43).

Kálal and a number of others assumed that Slovaks could not independently free themselves from the Hungarians and had to be helped by the Czechs. Not everyone was of the same view, though, some of the most prominent voices being the Slovak Roman Catholic priests Andrej Hlinka and František Jehlička (1879–1939) and the nationalistic politician Vojtech Tuka (1880–1946). In the 1930s they promoted autonomy and eventually separation of Slovakia and, in the case of the latter two, its reunification with Hungary. These sentiments were shared by many Hungarian politicians and writers who called for reestablishment of the Kingdom of Hungary with Slovakia as either part of Hungary or as an independent political unit. Lajos Steier’s infamous treatise There’s no Czech Culture in Upper Hungary (Reference Lajos1920), for example, disputed any Czech cultural connections with Slovak art in favour of the authenticity of Slovak culture. The historian and journalist of Hungarian origin was highly critical of Czechoslovakism and claims of Czech and Slovak cultural connections while promoting Slovak autonomy (Steier Reference Steier1929).Footnote 4 Steier (1885–1938), opposing any Czechoslovak unity, therefore defended authenticity and distinctiveness of Slovak culture.

The discussions of the meaning of art and culture in Slovakia had been lively for decades in various circles in and outside of Slovakia and they were reborn with a new intensity in the interwar period. The question was whether Slovak culture was distinctive from Czech, Czechoslovak, or indeed Hungarian culture and what that meant in political terms. These debates, regarding to which extent was Slovak folk art autonomous and could still fit within the Czechoslovak culture idea, were subsequently reflected in the narratives that were used for Slovakia in the Czechoslovak pavilions. Slovakia was represented by her folk art, which made the region culturally distinctive and at the same time indicated its inferior economic position compared to Bohemia.

The Slovak Picture of Slovakia

Representing Slovakia abroad as a land of folk culture and mountainous landscapes could therefore be seen as a contradictory combination of various approaches. Much emphasis was put on the aesthetic qualities of folk culture rather than its ethnographic relevance. As the Czechoslovak national pavilions did not provide much space or time for elaborate explanations of the internal politics and complex histories, Slovak culture became reduced to a visually interesting phenomenon: the land of shepherds, mountains, and lace making. However, although the narrative displayed in the Czechoslovak pavilions was in major part constructed in Prague, the rhetoric of Slovak embedment in folk culture had a long history in Slovakia too, going back to poet Ján Kollár’s (1793–1852) idealized poetic descriptions of the farming and shepherding people (Kodajová Reference Kodajová and Goněc2008, 57). In the second half of the 19th century, although the Slovak revivalists often criticized the Slovak people as passive towards political and national emancipation, they also emphasized the role of peasants as bearers of the folk culture which should protect the nation against assimilation (Kodajová Reference Kodajová and Goněc2008, 58).

During the first few years of the new republic, Milan Hodža (1878–1944), an influential nationalist Slovak politician and historian, who in 1918 became leader of the Czechoslovak Agrarian Party, upheld his turn of the century rhetoric of the naturally practical and collaborative Slovaks. They, in his view, consisted of rural people and farmers, skilled in hand and shrewd in head, and against them he placed the “arrogant, fainéant [lazy], reactionary, factious aristocrats” of Hungary (Hodža [1907] Reference Hodža1930, 145). For Hodža, Slovak national awareness derived from the humble virtues of traditional peasantry. He thus argued that Slavic connections, which were retained in the core of the nation and formed the basis for the new union with the Czechs, survived among the Slovaks. Hodža’s opinions were representative of the Slovak social and political elites who adopted their rural image and used it to their advantage, cultivating close ties between the Slovak people, agriculture, and peasant life in order to stress their rootedness in the land.

Evidence of such a historic connection with the land and hence the ancient character of the people was seen in folk costumes, embroidery, and ornamental decorations. For that reason, they frequently appeared in various exhibitions of Slovak embroidery and ceramics held for example in Vienna, Paris, and London before the First World War (“Voľná” 1913, “Výstava” 1913). The one in Vienna in 1913 was very successful according to newspaper reports, which saw the exhibited objects as works of pure art (Vajanský Reference Vajanský1972). Important was also calling the display Slovak and not associating it with the Hungarian and Upper-Hungarian geo-political and cultural context.

This attitude carried over into the joint Czechoslovak displays in the interwar period. Despite the predominance of Czechs in organizing the exhibitions, some Slovaks were involved too. Their input, nevertheless, did not challenge the codified narrative of Slovakia as rural and mountainous, instead they seem to have identified with it. Two examples illustrate this. In Paris, in 1925, the Slovak display was partly put together by the Czechoslovak ambassador to France, Štefan Osuský (1889–1973), who was born in Slovakia, but spent most of his life in the US and France. He selected Slovak companies, which produced folk-inspired items for everyday use. The choice was rather successful as the textile artefacts by Detva, as well as the ceramics from Modra, were awarded grand prix. With the total number of the highest prizes for the different exhibitors in the Czechoslovak pavilion amounting to 54, the recognition of the Slovak folk artefacts led to a confirmation that this way of presenting the region was indeed effective.

Another example further illustrates the internalized image of rural Slovakia projected internationally. In the late 1930s, Slovak art made an appearance at separate exhibitions in New York and the world’s fair in San Francisco. At the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco in 1939, which coincided with the New York’s World’s Fair, Czechoslovakia did not have a separate national pavilion, only a national section in the International Hall and a representation in the pavilion of Fine Arts. While the general display of smaller items like glass, crystal, household utensils, and textiles was designed by the Czech couple Antonín and Charlotte Heythum, the fine art display was put together by the ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Vladimir Hurban, of Slovak origin, who was assisted by a Slovak artist Andrej Kováčik (1889–1953). Born in Budapest, Kováčik was a rather conservative figure and nationalist. He had already organized an earlier exhibition of about 250 works of Slovak art in New York in 1938, shown at the galleries of the Fine Art Society. The show was put together with the American Slovak League, an organization promoting the welfare of Slovaks in the US, and received positive reviews in the American press. The New York Times noted about the exhibition that “the picturesqueness [ … in] these portrayals of Slovakian countryside and its people” seen in “the glimpses of costume, pastime and the occupations of daily existence” provided a “further insight into racial characteristics of the artists and of their land” (“Contemporary” 1938, 185).

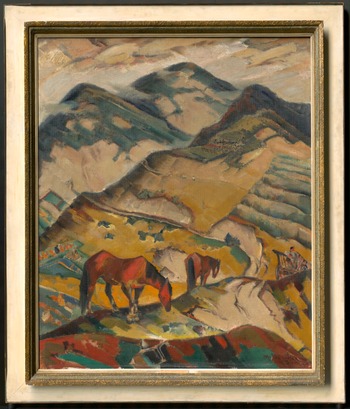

The choice of paintings in both New York and San Francisco consisted mainly of Slovak landscapes and works inspired by folk art. They were mainly by Slovak artists, such as Ĺudovít Fulla and Martin Benka, as well as by some Czechs – for instance František Malý, who depicted the Slovak countryside (figure 5). With works bearing titles such as “Countryside from Terchova,” “Wooden Church in Kezmarok,” or “Orava Castle,” Slovakia retained its rural image even in these cases which were in the hands of Slovak organizers (“Czechoslovakia” 1939, 14). Missing here, or in any other Czechoslovak displays, were any references to the modern architecture, art, and design of the Slovak cities of Bratislava and Košice, or the achievements of the so-called Slovak Bauhaus, the School of Arts and Crafts in Bratislava, founded in 1928 (Kolesár Reference Kolesár1996, Mojžišová Reference Mojžišová2013). More experimental works by the Slovak artists represented here, Fulla included, were also not present. These exclusions, whether deliberate or not, only confirmed the simplified and selective image of Slovakia which was reproduced by Czechs as well as Slovaks.

Figure 5. Martin Benka, Countryside from Terchova, oil on canvas. 1936. Slovak National Museum, Museum in Martin. Digitized as part of the Digital Museum project, carried out as part of OPIS, PO 2. The project was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund “Knowledge Economy Development” of the European Union.

Views from the outside: Czech and Slovak diaspora

Criticism of such reductive selection was not frequent, yet it appeared especially in regard to the limiting image Slovakia was given abroad, whether in the international exhibitions or elsewhere. And it was abroad where influential views of the new political entity and identity formed as the émigré communities played an important role in the way the Czechoslovak state and nation were understood. They were often involved in constructing the ideological content of the national pavilions, shaping the material as well as ideological content. The contribution of the émigrés was prominent in the briefly mentioned Czechoslovak pavilion in New York, which fell victim to the political crisis immediately before the Second World War. As Czechoslovakia disappeared from the political map, many exhibits failed to arrive to New York and new ones had to be acquired. The local diaspora thus provided their works of art, calendars, magazines, as well as folk artefacts which appeared alongside the intended, predominantly Czech displays. This included “a huge moral mosaic” of mediaeval Prague, accompanied by a mural of the Kings of Bohemia, a painting of the tenth century Prince Wenceslas, and replica of the crown jewels (“The Czechoslovak” 1939). The main hall contained examples of ceramic and heavy industries including a turbine, textiles and glass exhibits, and several sculptures.

In the USA, the Czech and Slovak diaspora was sizeable and in 1920 amounted to 600,000 each of Czechs and Slovaks. It played a significant role in both building the independent state during the First World War and constructing ideas of the nation during the interwar period (Auerhahn Reference Auerhahn, Horák, Chotek and Matiegka1936, 107). However, the image of the homeland, which these communities had often not seen for decades or ever, differed from the interwar reality (as much as the image of life abroad differed from reality in the minds of those who did not leave). The first generations left Austria-Hungary in the late 1800s and only experienced the creation of the nation-state of Czechoslovakia remotely. There were the exceptions of those who were involved in the efforts of Masaryk and his allies to raise American awareness of Czech – and eventually Czechoslovak – independence at the end of the war. Yet the Czechoslovak identity felt also remote. For instance, the Czechoslovak National Council of America, with a seat in Chicago, founded to support the efforts of creating an independent state, inconsistently referred in its communications to Bohemians, Czechs and Slovaks, Czechoslovaks, Czechs and Slavs, and “Czecho-slovaks” (Hájková Reference Hájková2011, 113).

There were also important generational divides among the émigrés that were important for how Czechoslovakia was viewed after 1918. Most of the first-generation Czechs in the United States self-identified as Czech based on their language. They maintained Czech associations such as Sokol, women’s clubs, legionaries clubs, community buildings, pubs, cooperatives, and so on (Jaklová Reference Jaklová2014, 58). Already at the end of the nineteenth century, the Czech Americans were quite engaged in cultural as well as trade affairs that involved the homeland, and this included taking part in world’s fairs and exhibitions at both ends. This could be seen in, for instance, the invitation of the composer Antonín Dvořák to perform at the Bohemian Day at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, exhibits of Czech Americans at the 1891 Jubilee Exhibition, and the 1895 Czechoslavic Ethnographic Exhibition in Prague.

Yet many Czechs of the second and third generations in the U.S. were more distanced from their parents’ and grandparents’ homeland, and according to some accounts were losing interest in their Czech heritage (Vojan Reference Vojan1939). Moreover, they had more in common with Americans or other ethnicities than the Slovaks with whom a joint state was created. The feeling of detachment of many young Czech Americans from the land of their parents and grandparents was often exacerbated by the image of Czechoslovakia that was projected in the United States through ethnographic films (Vojan Reference Vojan1939, 29). For instance, the popular documentary film Zem spieva (The Earth Sings) from 1933 by the Czech photographer and film maker Karel Plicka, depicting the seasonal cycle of rural life in Slovakia, was shown around the U.S. In Indiana, the former inhabitants of the Moravian Slovakia, “excellent and educated people,” complained that the depiction of the hardship and poverty of life in the rural regions harmed their efforts to present Czechoslovakia as a modern and affluent country (Vojan Reference Vojan1939, 29). Instead, they recommended to show “films with modern buildings and factories, [ … ] sports grounds, Sokol gatherings, skiing, in short, present the second generation with evidence that Czechoslovakia was a progressive country matching the American lifestyle” (Vojan Reference Vojan1939, 29). The article, which reported the anecdote, further suggested that annual visits of the second generation to Czechoslovakia could rectify understanding of the homeland, although obviously that was not achievable for many.

What was achievable, however, was the building of Czechoslovak pavilions at American world’s fairs. The interactions of the American Czechs and Slovaks with Czechoslovak pavilions therefore add to the understanding of the construction of Czechoslovak identity. Abroad, the Czechoslovak pavilions could become a substitute for the homeland the local diaspora would probably never see. This translated into an active involvement of Czech and Slovak émigrés in all the Czechoslovak pavilions or sections that were displayed in Philadelphia (1926), Chicago (1933/34), San Francisco (1939/40), and New York (1939/40).

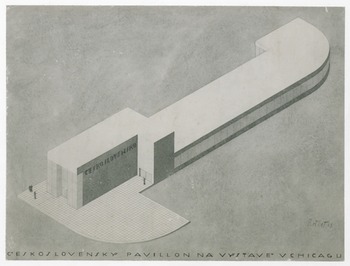

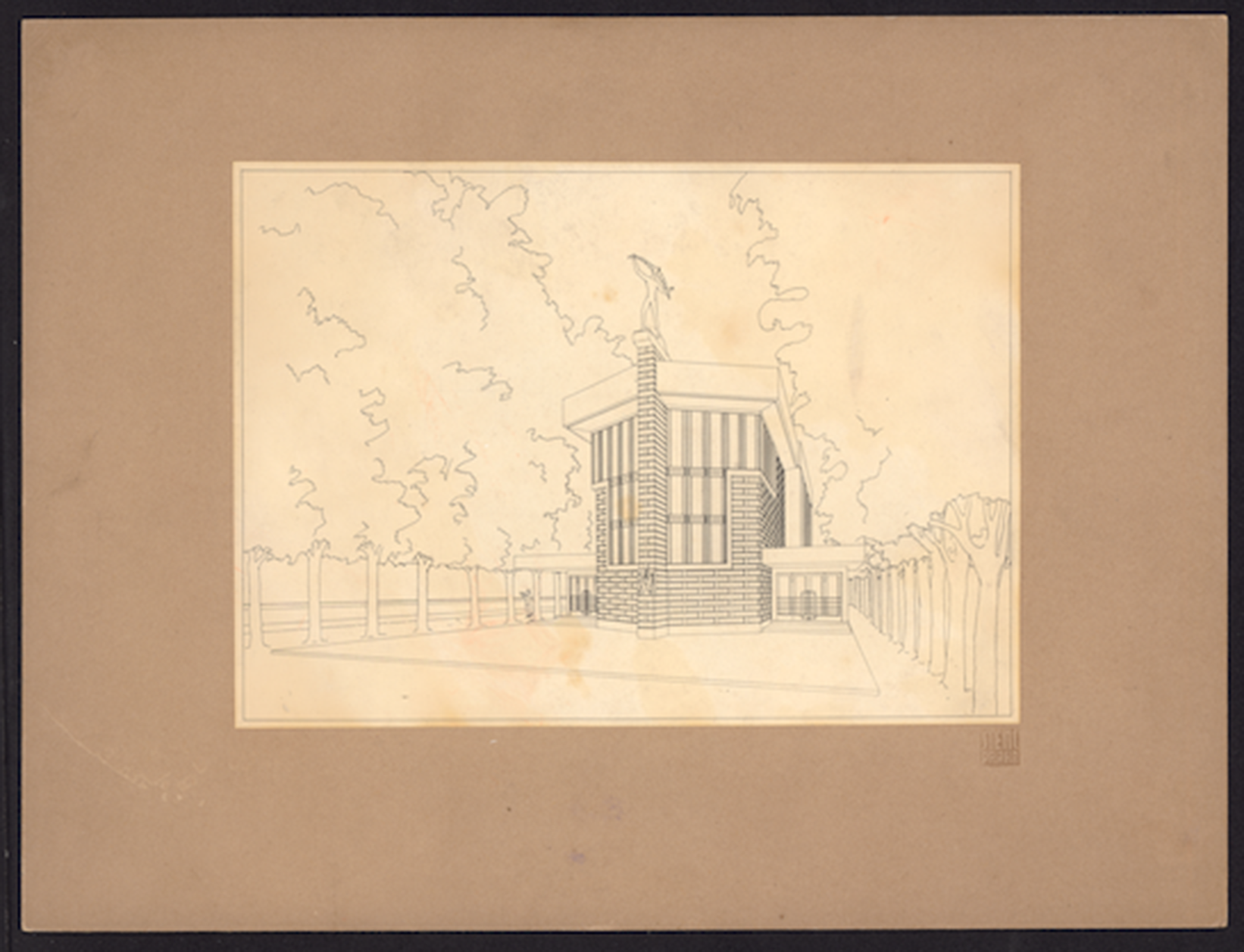

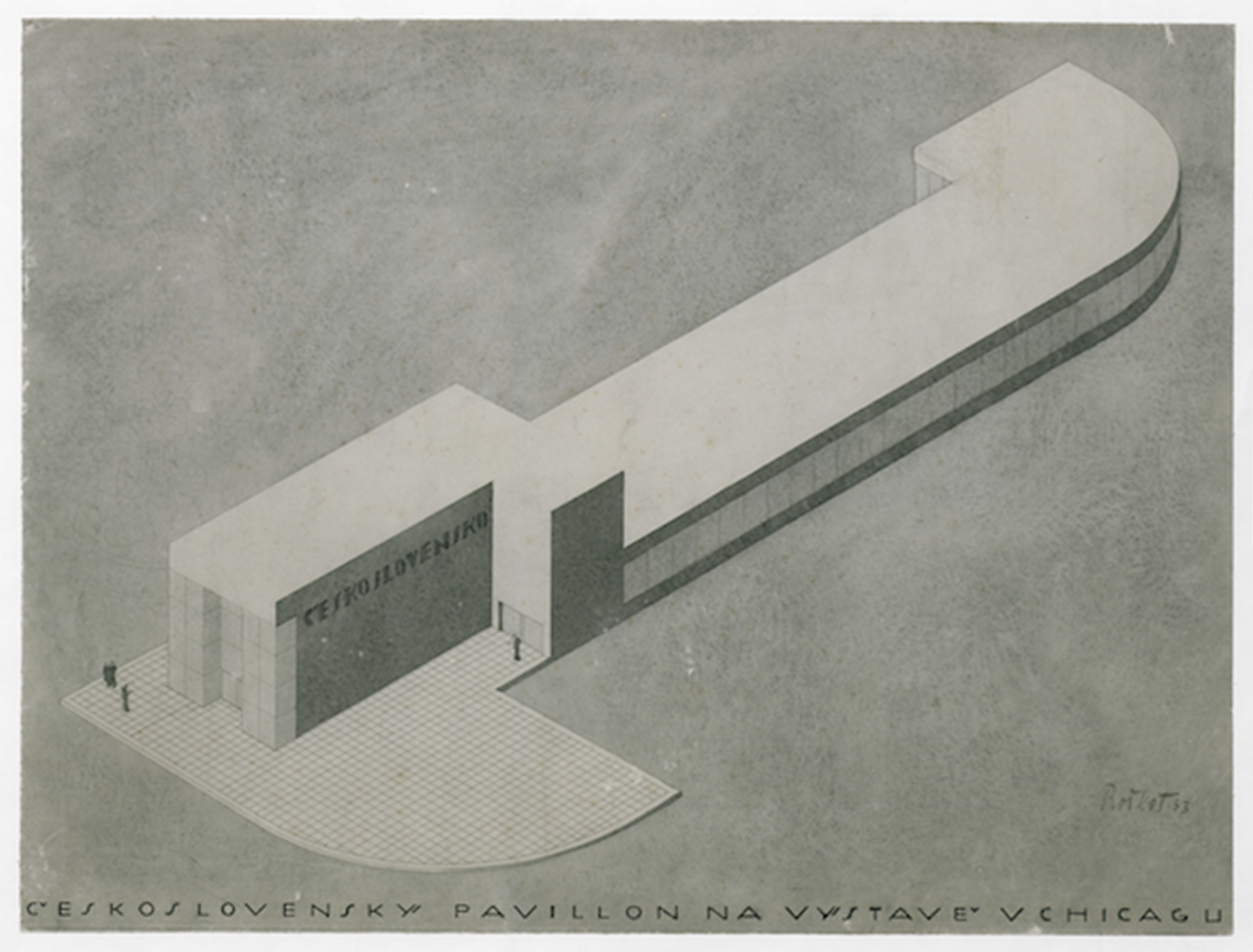

Their engagement was particularly prominent in Chicago, where a sizeable community of about 200,000 Czechs lived. The pavilion itself was designed by Kamil Roškot as a simple building with a large, tall, glass entrance decorated by a mosaic of the Czechoslovak emblem (figure 6). The lower, second part of the building extended in a rectangle curved at one end and had a strip of glass around it. The large entrance hall was again fitted with a statue of President Masaryk flanked by a panorama of Prague and the Slovak Tatra mountains. Around 70 companies participated in the display of industries, tourism, agriculture, and transportation in Czechoslovakia, with emphasis on spas (“Official” 1934, 22). The industrial design section featured mainly Czech textiles, glass, porcelain, embroidery and jewellery, while Detva represented Slovakia. There was also a Czechoslovak America exhibit which contained statistical information on the number of Czechs and Slovaks and their organizations, books on Czechoslovakia, and newspapers published in the United States, coins, as well as a ship propeller, an invention that “had direct and long-lasting impact on the development of the American civilisation” (“Czechs” Reference Vojan and Laučík1933, 106).

Figure 6. Kamil Roškot, Czechoslovak pavilion, Chicago, 1933, National Technical Museum, Prague, Museum of Architecture and Engineering, fond 39 Roškot.

During the preparatory negotiations, the prospect of a Czechoslovak pavilion was welcomed by many members of the local Czech and Slovak diaspora in Chicago. It had been actively calling for a Czechoslovak pavilion during the initial stages of the fair, by which it fought the initial reluctance of the Czechoslovak government wary of the difficult economic climate of the early 1930s. This included a personal visit to Czechoslovakia by the mayor of Chicago. Having Czech roots, Antonín Čermák left for the US with his family when he was little. He became a businessman and a Democratic politician, and eventually was elected a mayor of Chicago in 1931. Czechoslovakia became the first stop on his tour of Europe to lobby for the participation of countries and companies in the planned World’s Fair. This fact was seen in Czechoslovakia as a proof of the importance of the country’s presence not only for the extensive émigré community but for the global audience too.

In Czechoslovakia, Čermák partly represented the Czechs of Chicago as he saw the exhibition as “an excellent opportunity to show the best of Czechoslovak industries and arts not only to Chicago but to the whole United States and the world” (Vlček Reference Vlček1935, 329). With this, he wanted to counter the derogatory assumptions about the backward nature of the Czechoslovak nation promoted by Čermák’s rival and predecessor, William Thompson. The emphasis was put on the involvement of local companies with Czech ownership. The presence of a national pavilion at the Century of Progress was therefore significant for the diaspora and their connection with the now independent homeland. Prior to the exhibition, the Czechoslovak consulate general was quite explicit about this when he stated that the Czechoslovak participation was seen as important for the Czechs (and Slovaks) in Chicago. He pinpointed the young generation of Czech Americans, in whom “we entrust the legacy of the national endeavour, and in which we try to preserve the love and pride in their Czechoslovak roots.” Most probably aware of the distancing of the second generation from the homeland, he appealed to the shared cultural roots: “… we can show [ … ] to those who mostly never stepped on the Czechoslovak ground the achievements and cultural prowess of the Czech and Slovak race [nation]” (“General” 1932). It should, however, be reiterated that most of the references to the Czechoslovak roots, nation, and state again operated within the ideology of Czechoslovakism with a much more dominant Czech identity and culture. The external homeland created by the Czechoslovak pavilion therefore replicated the situation in the state itself. The involvement of the diaspora in the shaping of the Czechoslovak displays, nevertheless, indicates the importance of these events not only for establishing trade and political relationships but also for retaining a sense of homeland.

Conclusion

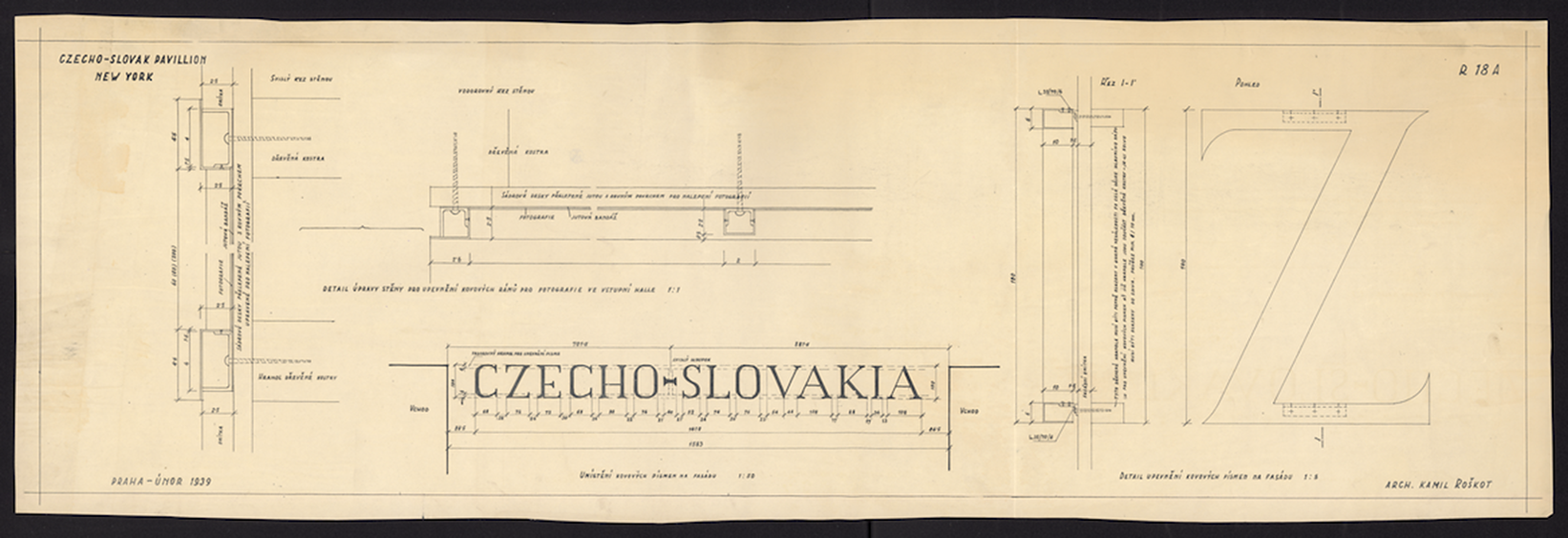

The continued presence of Czechoslovakia at all major international exhibitions in the interwar period can be taken as proof of the success of the country’s participation. Nevertheless, it came to an abrupt end when, following the Munich Agreement, the border regions of the Sudetenland were ceded to Germany in September 1938. The Czechoslovak state was restructured into Czecho-Slovakia, with Slovakia and Ruthenia as autonomous regions. The pavilion planned for New York also received a hyphen to reflect the new situation and became dedicated to Czecho-Slovakia (figure 7). The two provinces were now separated by political administration as well as a punctuation mark. In March 1939, Czechoslovakia was ultimately invaded by Germany and turned into two entities: the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on the one hand and the Slovak Republic on the other. In New York, Czechoslovak minister Hurban, mayor La Guardia, president of the fair Grover Whalen, and Czechoslovak commissioner general George Janeček replaced the organizers of the now disappeared state and continued the administration of the Czechoslovak display. Even though the new individuals in charge were external to the state, they kept most of the original ideology of the previous Czechoslovak pavilions which had been established throughout the interwar period. This was obvious in the visual representation of Czechoslovakia outlined at the start, in Čapek’s quotation, as well as in many other artifacts throughout the pavilion which put emphasis on Bohemia as the industrial centre, while Slovakia was once again portrayed as traditional. Even though Czechoslovakism was now a thing of the past, undertones of the ideology survived in many aspects of the pavilion. They indicated the continuity of the idea of the Czechoslovak nation, despite the fact that the Czechoslovak state no longer existed. The Czechoslovak national day, for instance, which took place on July 28, 1940, adhered to listing things as “Czechoslovak,” and included the performances of Czechoslovak bands and Czechoslovak folk songs and signified “the unity of the Czechoslovak people. They [were to] show that the Czechoslovak Nation is still alive, though the expression of its real existence may be shown today only by its sons and daughters, here, on the free soil of the United States of America” (“Tentative” 1940).

Figure 7. Inscription Czecho-Slovakia, New York World’s Fair, 1939-40. National Technical Museum, Prague, Museum of Architecture and Engineering, fond 39 Roškot.

This insistence on promoting the Czechoslovak nation at the World’s Fair, beyond the state’s lifespan, indicates that the notion of the single nation was in part created, imagined, and replicated for display at international exhibitions. During the interwar period, the state actively formulated the idea of the nation, which was on the one hand homogeneous, on the other culturally and economically diverse. The important differences between the western, Czech speaking and the eastern, Slovak speaking lands were upheld and simplified in the pavilions into a juxtaposition between modern, progressive, and industrial on the one hand, and rural, traditional, and folk on the other. The resultant message, indeed, created a land of contrasts, as Čapek called it, and “the highly civilised” western part was placed against “the very simple east.” However, this message, not only at exhibitions, was increasing disputed by many recipients and led to the eventual fall out of the Slovaks and the Czechs and their political separation. Despite the concerted effort to present a unified picture of the imagined nation as an “island of democracy,” the nationalizing project failed. One of the main reasons for this failure was that the idea of the single Czechoslovak nation was built and visualized on simplified contradictions, which marginalized the multi-ethnic aspect of the Czechoslovak nation in favour of the cultural and political advancement of Czechs.

Financial Support

This article is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 786314).

Disclosures

None.