Such is the imperfect sketch my memory has furnished me with of the manners and customs of the people among whom I first drew my breath. And here I cannot forbear suggesting what has long struck me very forcibly, namely, the strong analogy which even by this sketch, imperfect as it is, appears to prevail in the manners and customs of my countrymen and those of the Jews, before they reached the Land of Promise, and particularly the patriarchs while they were yet in that pastoral state which is described in Genesis – an analogy, which alone would induce me to think that the one people had sprung from the other.

– Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The AfricanIntroduction

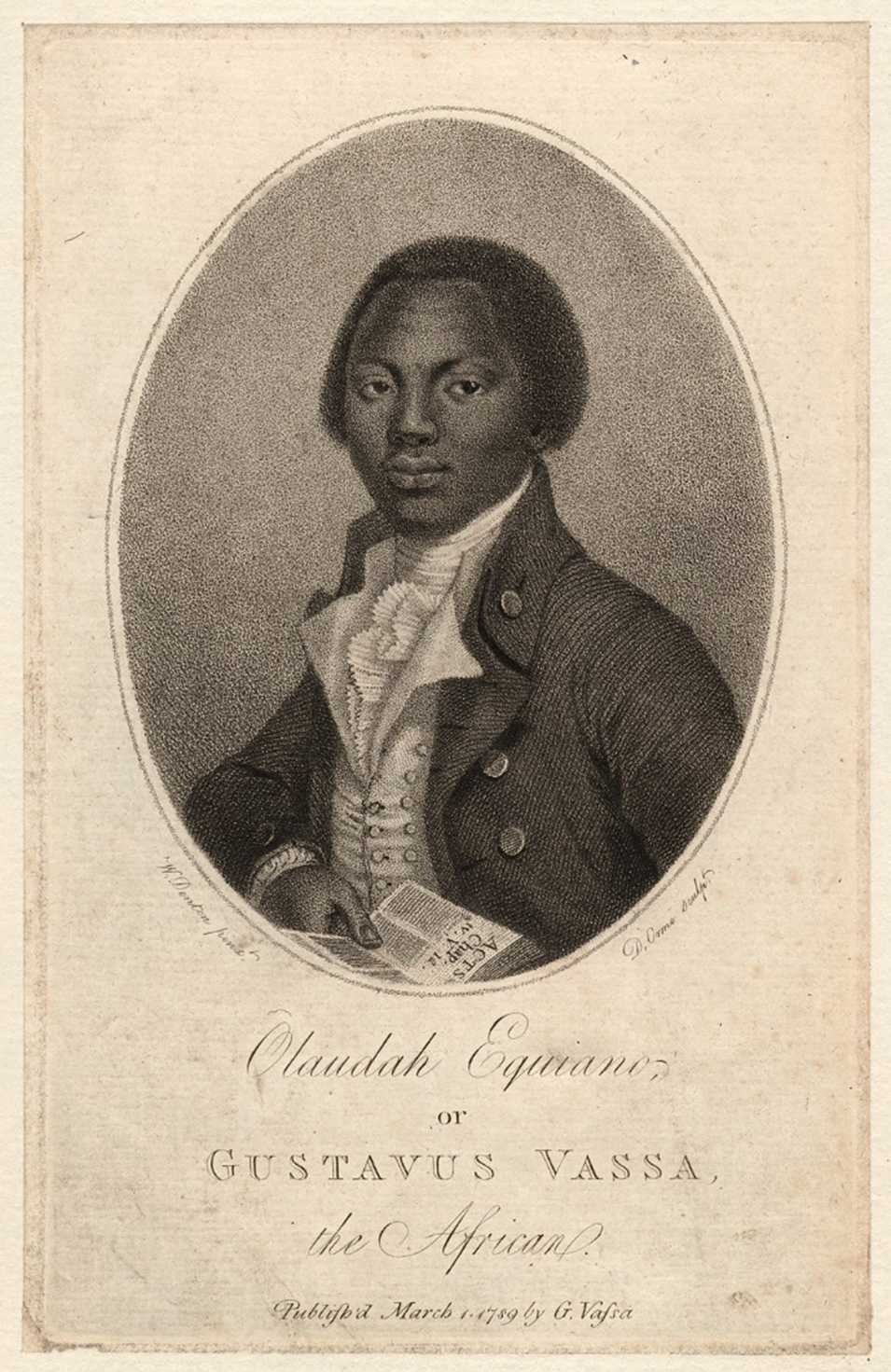

Olaudah Equiano (1745–1797) has an outstanding reputation as one of the first freedmen and abolitionists to document a personal – undoubtedly captivating – account of his dispossession from his native IgbolandFootnote 1 in what would later become a part of present-day Nigeria. However, little is known about his staunch belief that the Igbo – the dominant ethnic group in current southeastern Nigeria and the third largest ethnic group in the Nigerian federation after the Hausa and Yoruba – have a connection to Jews axiomatic from the cultural similarities between both groups with regard to animal sacrifices, marriage customs, circumcision rites, purity taboos, agricultural practices, and so on. These cultural similarities stimulated Equiano (see figure 1), as far back as the 1700s during the so-called Age of Enlightenment which was paradoxically the era of exaltation of the horrid Atlantic slave trade, to contend that the Igbos are not just descendants of Jewish people but also literally Jews and that Africans should, like him – a freedman, Englishman, writer, and avid abolitionist – be accorded respect through the abolishment of the slave trade. Of course, Equiano’s slave narrative predates Nigeria which only became a sovereign state in 1960 so that his analogies of the intricate uniformity of Igbo and Jewish cultures were not meant to engender nationalist sentiments but to critique the racialism embedded in Enlightenment thinking in his time that posited savagery and moral ineptitude as the natural aptitude of the African slave relative to the European slaver, thereby denying the former her liberty and dignity. In other words, the justification for the Atlantic slave trade during the Enlightenment was the supposed “prelogical mentality” (Lévy-Bruhl Reference Lévy-Bruhl1910) of the African that necessitated cultivating in her – through deracination and servitude – aspirations toward the “logical mentality” of the European. This was the hegemonic ideology prevalent in western societies that Equiano – a contemporary as much of racist Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire, Immanuel Kant, and David Hume as of the feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, the economist Adam Smith, the German playwright Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the Romantic poet Robert Burns, and the racist Founding Father of the United States, Thomas Jefferson (see Appiah (Reference Appiah, Appiah and Gutmann1996, 30–105), for a thorough discussion of Jefferson’s racist theories) – challenged in his slave narrative entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, published in 1789. Equiano’s narrative is, to a certain extent, an antecedent of the accurate observations of Horkheimer and Adorno (Reference Horkheimer, Adorno, Noerr and Jephcott2002, 1) regarding the paradox, nay contradiction, of the Age of Enlightenment: “Enlightenment, understood in the widest sense as the advance of thought, has always aimed at liberating human beings from fear and installing them as masters. Yet the wholly enlightened earth is radiant with triumphant calamity.” For – so Equiano seemed to wonder – how could the Enlightenment with all its accentuation of reason, tolerance, progress, fraternity, and liberty be coterminous with a “triumphant calamity” such as slavery that denied liberty to black people for white Europeans’ economic luxury and satiation? The Enlightenment, for Equiano, was quite unenlightened. This oxymoron – that is, the unenlightened Enlightenment – as well as Equiano’s place in combatting it is underscored by Eke (Reference Eke and Korieh2009, 31):

Interestingly, eighteenth century Enlightenment by its “Declaration of the rights of man” asserted the universality of human rights. Ironically, those rights were not extended to nations and cultures outside Europe, in this case Africa and the colonies or economic outposts in the Americas and elsewhere. Hence, while Europe was proclaiming the “rights of [m]an,” it was simultaneously denying them to Africans and exporting them because they were not necessarily seen, read, or defined as “men,” human beings. Also, affected by this ironic application of European enlightenment values were blacks in the New World and the indigenous peoples of the Americas and Caribbean. Even when those ideas were extended to Africans, they were still defined as “other,” and particularly in terms of the “noble savage.” Indeed, the ideals of enlightenment Europe were contradictory[,] and Equiano’s narrative occupies a space where the tensions are clearly manifested – the extension of the “rights of man” or human rights to Africans (free and enslaved).

Figure 1. Portrait of the Writer and Abolitionist Olaudah Equiano

Source: Reproduced with permission of National Portrait Gallery, UK

Equiano’s slave narrative simultaneously humanized the African and underscored the malevolence of indentured servitude and slavery. Indeed, he “saw his own life as a testament of slavery on the one hand, and on the other hand, a witness to the integrity, civility and humanity of the black man that were being called to question” (Acholonu Reference Acholonu and Korieh2009, 51). Whereas Equiano’s short-lived sojourn lent significance to the “original” cultured – civilized – nature of the African prior to her deracination by European slavers, his analogy of the cultural similarities between Jews and Igbos was geared toward demonstrating a “commonality with an ancient culture that his audience recognizes. How can his audience reject his culture and religion without implicitly rejecting that of the Jewish people of the Old Testament?” (Eke Reference Eke and Korieh2009, 35). Consequently, Equiano’s preoccupation was not so much about Igbo nationalism (such ethnic nationalism did not even exist in his day) or Biafran separatism (Nigeria was non-existent in the 1700s) but about the havoc that the unjust capitalist-like slavery system wreaked on Africans and the need to build a fairer society sans servitude for black people. His unwavering involvement in abolitionist movements such as the Sons of Africa in Imperial Britain coupled with his book tours, newspaper commentaries, advertisements, and public endorsements quickly earned him a celebrity status – he was, in Ryan Hanley’s measured words, a “celebrity abolitionist” – as “[t]he fight against slavery, in which he was so indefatigably and consistently engaged, provided a locus of influence and a moral foundation for his publicity-generating activities in provincial Britain” (Hanley Reference Hanley2018, 74).

It would take more than a century for Equiano’s analogy, however unsubstantiated, to be considered factual by Igbo nationalists. Indeed, during the gory Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970) that saw millions of Igbos maimed, massacred, and starved to death – an episode in Nigeria’s troubled history that has been memorialized in several novels and memoirs including inter alia Flora Nwapa’s Never Again (Reference Nwapa1975), Buchi Emecheta’s Destination Biafra (Reference Emecheta1982), Anthonia Kalu’s Broken Lives and Other Stories (Reference Kalu2003), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun (Reference Adichie2006), and Chinua Achebe’s There Was A Country: A Personal History of Biafra (Reference Achebe2013) – the supposition that the Igbos are the “lost tribes of Israel” orientated Igbo nationalism. Nowadays, there are several Igbos – nationalists, academics, elites, and common people – for whom Jewishness is not just a historical analogy, as it appeared to be for Olaudah Equiano, but an empirical fact amenable to scientific experimentation through DNA tests. In other words, they believe that they were, in fact, genetically Jewish prior to the advent of the “twin menaces” of Christianity and European colonialism in Nigeria that disrupted Igbo culture so that practicing Judaism and claiming Jewishness are simply about reclaiming a lost heritage (Alaezi Reference Alaezi1999; Ogbukagu Reference Ogbukagu2001; Ilona Reference Ilona2019; Subramanian Reference Subramanian2022). However, some scholars have rebuffed the veracity of the claim as nothing but a myth (Afigbo Reference Afigbo1983; Parfitt Reference Parfitt2003 because the “[o]ral traditions of the people, archaeological, and linguistic evidence show that the Igbo had emerged as a distinct group more than 6,000 years ago” (Chuku Reference Chuku2018, 4). Others have shown that the Igbo claims of Jewish heritage are embedded in the Hamitic Hypothesis – a longstanding racialist discourse that Europeans used to justify the oppression of black people – that is overwhelmingly irrelevant in comprehending the origins of peoples (Parfitt Reference Parfitt, Bruder and Parfitt2012, 12–30; Bruder Reference Bruder2008). (I shall say more about the Hamitic Hypothesis in the third section of this article.) Still, others – like the Jewish Voice Ministries International – have gone as far as conducting “controversial” DNA tests to verify the Igbo claims of Jewish ancestry and concluded that the results “did not support their [the Igbos’] claim to be descendants of the ancient people of Israel” (Kestenbaum Reference Kestenbaum2017). These counterclaims have not halted Igbos’ claims of being Jewish; rather, it has even infuriated some who have now rejected the results with the forceful contention that DNA tests of that sort are incapable of proving – or disproving – Jewishness. Denouncing the DNA tests, for example, Remy Ilona – one of the ardent champions of the idea of the Jewishness of Igbos – contends that “[t]here is no test that can prove Jewishness. The culture has to point in that direction, and maybe a test can confirm what the culture is already saying. The Igbos that are connecting to Judaism have no connection to these DNA tests and we oppose this” (Lidman Reference Lidman2017). Evidently, this cultural belief amongst some Igbos has proved virtually impossible to discard regardless of the scientific evidence provided to counteract it.

Whether the Jewishness of Igbos is actually true or false is an ongoing debate that strikes at the heart of Jewish identity, for it raises the following critical question: “Who is a Jew and what defines Jewish identity?” Reflecting on “Igbo Jews” whom he calls “Jubos” as to whether Jewish identity should be ascribed to Igbos, William Miles raises pertinent questions:

So why don’t we automatically embrace the Jubos as our own? What justifies the sense – especially among the non-observant cultural or ethnic Jews, not to mention the agnostic or atheistic – that they are “real” Jews, and the Jubos are not? Ethnic Jews take their Jewishness for granted; but in discounting the religious element, are they not thoughtlessly discounting non-ethnic Jews who do assume the mantle of Judaism? Does Judaism not belong to whoever takes it upon him or herself? Why should Ashkenazi intellectuals who reject Judaism be considered more authentic Jews than Igbos who embrace it? To put it more bluntly, has the understanding of Judaism as a race overshadowed the understanding of Judaism as a religion? And finally, if Judaism is viewed in racial terms, how did it become white in global eyes? (Miles Reference Miles2011, 44)

As I shall explain in the article, the Jews themselves are divided on the matter and as to whether to extend Jewishness to “African Jewry” such as the Igbo. What is undoubtedly lucid, I suspect, from the claim is the employment of analogical reasoning by Igbo nationalists to accentuate the Jewishness of Igbos. For by underlining similarities between Igbo customs and Jewish traditions, Igbo nationalists decipher the resources to postulate that they are connected in every way possible – including genetically and politically – to Jewish people. The role of analogical reasoning in group decision-making, including foreign policy, is not entirely novel in international relations (May Reference May1973; Jervis Reference Jervis1976; Khong Reference Khong1992; Mumford Reference Mumford2015). The international relations expert Yuen Foong Khong (Reference Khong1992, 6–7) defines historical analogy as “an inference that if two or more events separated in time agree in one respect, then they may also agree in another.” Or, as he puts it more formally:

Analogical reasoning may be represented thus: AX:BX::AY:BY. In words, event A resembles event B in having characteristic X; A also has characteristic Y; therefore it is inferred that B also has characteristic Y. The unknown BY is inferred from the three known terms on the assumption that “a symmetrical due ratio, or proportion, exists.” (Khong Reference Khong1992, 7)

The above schematism seems to be what Igbo nationalists do when they invoke Jewishness – that is, when they draw parallels between Jewish customs/discrimination in Central and Eastern Europe and Igbo traditions/discrimination in Nigeria. The research question engendered is this: Why do Igbo nationalists subscribe to the view that Igbos are Jews despite evidence against such historical ties? To answer this question, it seems to me that the focus should be not so much whether the analogies are logically sound but why they are instrumentally useful to the ethnic group in question. In other words, the focus should be about what such analogies do. Drawing on psychology, Khong (Reference Khong1992, 13) contends that analogical reasoning aid people to “order, interpret, and simplify, in a word, to make sense of their environment. Matching each new instance with instances stored in memory is then a major way human beings comprehend their world.” In the context of the nationalist’s resort to analogical reasoning, I contend that such analogies founded on “imagined community” (Anderson Reference Anderson1983) with Jews serves as the lens via which Igbo nationalists collectively organize but also make case for ontological security – for the security of Igbo identity – in circumstances of perceived prejudice, stereotype, and invidious discrimination that might annihilate Igbos in postcolonial Nigeria. Hence, the unique Jewish historical narrative of assimilation, antisemitism, and ultimate realisation of Jewish statehood for the safeguarding of Jewish identity is a frame of reference that drives Igbo nationalists to justify their political cause for a sovereign state, to seek approval from the international community, and to forge novel identities amidst the obstinate marginalisation of the Igbo in Nigeria. Indeed, by employing the analogies, Igbo nationalists considered – and still consider – themselves as a unique ethnoracial and ethnoreligious group countering ethnic, racial, and religious oppression in Nigeria all of which can be best eradicated through the establishment of an independent state – Biafra. This is precisely why Harnischfeger (Reference Harnischfeger, de Vries, Englebert and Schomerus2019) is quite right, I think, to argue that the secessionist agitation amongst Igbo nationalists in the southeast geopolitical zone is an “instrument of political bargaining” to transcend the multifarious malaises of the Nigerian political system.

This article is organized around four sections. In the first section, I delve into the ontological security literature to explain its meaning and operationalization in the context of my research. I understand ontological security to mean the security of ethnic groups in terms of the stability of various components of their identity including, inter alia, culture, territory, and religion. Ontological insecurity, by contrast, is the existential anxiety amongst groups that the significant components of their identity are under existential threat from the activities of other groups. This leads the ontological insecure ethnic group to defend its interests against those that threaten its security. In the second section, I shall analyze the Jewish conception of Jewish history and Jewish identity focusing on the reason for the rise of Jewish nationalism in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the eventual creation of the Jewish state in the Land of Israel. I will also explain what the State of Israel signifies for Jewish people in contemporary time and the ontological dissonance the state faces as it navigates its complex identities. In the third section, I shall examine Igbo history, the colonial cum racial roots of the Hamitic Hypothesis and its internalization and resonance amongst the Igbo. In the fourth section, I assess the Igbo search for ontological security amidst rampant pogroms in the northern Nigeria and the arguments put forward by Igbo nationalists during the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970) to defend their identity against persecution and discrimination by northern – predominantly Muslim – Nigerians. I shall explicate the social power of Igbo nationalists’ analogical reasoning in terms of how it, at one and the same time, impacted the international community and shaped humanitarian activism in the modern world. And, in the conclusion, I shall restate my argument regarding the reason for the Igbo nationalists’ analogy of Jewishness and how it continues to orientate Igbo nationalism in contemporary Nigeria.

Conceptualizing Ontological Security

The core thesis of ontological security theory, despite the varied levels of analysis used by scholars working with the theory, is that individuals and groups are invariably committed to maintaining the components of their identity – that is, whatever make them who they are and give them continuity such as culture, religion, territory, language, and the like – so that any factor or event which appears as an existential threat to, or tries to change, one or more components of their identity would be fiercely resisted or rejected (Giddens Reference Giddens1991; Kinnvall Reference Kinnvall2004; Laing Reference Laing1960; Rumelili Reference Rumelili2015). As Sigel (Reference Sigel1989, 459) puts it, “There exists in humans a powerful drive to maintain the sense of one’s identity, a sense of continuity that allays fear of changing too fast or being changed against one’s will by outside forces.” Similarly, Lupovici (Reference Lupovici2012, 812) defines ontological security as “security of being rather than security of surviving (physical security); and to maintain it, actors must not only be identified by others as having specific identities, but they also need to be able to assure themselves of who they are.” Kinnvall (Reference Kinnvall2004, 741–742) contends, for example, that the reason for anti-immigration and anti-globalization sentiments in the West stems in large measure from Westerners’ feeling that the key components of their identity – culture, territory, religion, say – are under threat from immigrants, refugees, Muslims, and the seemingly inexorable forces of globalization. Exclusionary nationalism and populism thus serve as the avenues for some Westerners to reaffirm a threatened self-identity. Ontological security involves trust in relationships between two or more parties, one that gets rid of existential anxiety. In deeply divided societies where conflicts amongst ethnic groups are ubiquitous, conflicts tend to become protracted despite well-intentioned peace negotiations because warring groups distrust one another and feel that acceptance of peace agreements would mean the erosion of components of their identity that matter for their continuity (Rumelili Reference Rumelili2015, 20–23; Mitzen Reference Mitzen2006). Ontological security is the “security not of the body but of the self, the subjective sense of who one is, which enables and motivates action and choice” (Mitzen Reference Mitzen2006, 344). Ontological insecurity, by contrast, is the extreme state “where anxieties that can no longer be contained by existing social and political processes are unleashed in varying ways and to varying degrees” (Rumelili Reference Rumelili2015, 12). The ontologically insecure “lacks a consistent feeling of biographical continuity, and … becomes obsessively preoccupied with apprehension of possible risks to his or her existence” (Giddens Reference Giddens1991, 53).

Prior to the development of the concept of ontological security, international relations scholars explained security mostly in terms of physical security – that is, the survival of states in an anarchic international society which includes strategies such as friendly alliances (balancing and bandwagoning), favorable geographies, and large militaries (see Waltz Reference Waltz1979; Bull Reference Bull1977). There was no concern for the ontological security of states. Though ontological security and physical security are analytically distinct, ontological security theorists contend that they are not necessarily mutually exclusive in that physical security could be necessary for ontological security as without the former a particular group’s being and identity might be quashed. Conversely, an entity could risk its physical security for the sake of safeguarding its ontological security (Mitzen Reference Mitzen2006). Accordingly, whilst ontological security cannot be reduced to physical security and vice versa, they are almost always intricately intertwined.

Although the first theorists of ontological security – notably, RD Laing (psychoanalysis) and Anthony Giddens (sociology) – were concerned about the individual level as a unit of analysis, international relations theorists adapted the theory to explicate state behavior with the contention that states do not care only about physical security (and survival) but also about the continuity of being and identity; and in some cases, states could sacrifice physical security for ontological security. But the shift from the individual to the state as the unit of analysis has been criticized in the international relations literature. For instance, there are questions regarding the age-old “level of analysis” problem as well as the anthropomorphizing of states as entities with emotions and anxieties. Indeed, scholars have argued that “resorting to the assumption of state personhood obscures important aspects of how the state, as an evolving institution, affects individuals’ sense of ontological security” (Krolikowski Reference Krolikowski2008, 111; also see Mälksoo Reference Mälksoo2015). These critics contend that whilst it is true that the state provides ontological security for individuals or groups, one cannot infer from this premise that states are unitary actors, have needs to be ontologically secure like individuals, or that they are ontological security providers. Kinnvall and Mitzen (Reference Kinnvall and Mitzen2017, 6–9) counter these by posting that the criticisms are not so much a critique of ontological security theory but of the assumption of the state as actor. Further, Mitzen (Reference Mitzen2006) and Steele (Reference Steele2008) address this “level of analysis” conundrum by accentuating that just as international relations theorists employ the notion of the “body” – which may be synonymous with territory or people – and emotions as an “as if” – that is, as an idealization (Vaihinger Reference Vaihinger1924; Appiah Reference Appiah2017) that may not necessarily reflect reality but is instrumentally useful to explicate reality – to delimit physical security and state behavior, the same heuristic could, in like manner, be employed in the case of ontological security. In other words, with ontological security the state could equally be personified and therefore considered a person with emotions and anxieties projected through its elites whose sense of self or agency may be threatened when the state itself is bedevilled by myriad factors in world politics. This explains why Rumelili (Reference Rumelili2015, 17) posits that “what makes it appropriate to apply the concept at the level of states is that the peace anxieties that are experienced individually and collectively by elites produce aggregate behavioral outcomes that are analogous to those at the individual level.”

The last decade has witnessed the flourishing of ontological security theory in sociology, political science, and international relations. Indeed, the framework has been employed to address theoretical and empirical conundrums ranging from globalization and religious nationalism (Kinnvall Reference Kinnvall2004), national belonging and nationalist politics (Kinnvall Reference Kinnvall2018; Skey Reference Skey2010), state personhood, security, and identity (Berenskoetter and Giegerich Reference Berenskoetter and Giegerich2010; Krolikowski Reference Krolikowski2008), domestic policymaking (Lupovici Reference Lupovici2012), memory politics and post-conflict reconciliation (Rumelili Reference Rumelili2018; Subotić Reference Subotić2016), information warfare (Bolton Reference Bolton2021) to governmentality and ideology (Marlow Reference Marlow2002), social movements (Solomon Reference Solomon2018), state denial of historical crimes (Zarakol Reference Zarakol2010), the European Union’s Eastern Neighbourhood Policy (Browning Reference Browning2018), state revisionism (Behravesh Reference Behravesh2018), conflict resolution (Rumelili Reference Rumelili2015), diaspora and transnational migration (Abramson Reference Abramson2019), human security (Shani Reference Shani2017), great power narcissism (Hagström Reference Hagström2021), and humanitarian interventions (Steele Reference Steele2008). Because of the diversity of conundrums that draw on the framework, some scholars – Steele (Reference Steele2019) amongst them – advocate that it should be regarded not so much as ontological security theory but as ontological security studies. What the various applications of the ontological security framework share in common, so it seems to me, is emphasis on the security of identity and continuity of routines without disruptions.

Given that my research is centered on ethnonationalism and nationalist self-determination, in this article I employ ontological security to refer to an ethnic group’s sense of identity and desire for continuity which may be threatened through repression, marginalization, and extermination. Ethnic groups desire continuity with their way of life; they want their identities secure. Although, in principle, the state is supposed to provide ontological security for every group that inhabits it, it is oftentimes the case, in practice, that state institutions are deployed to oppress and dominate people – especially national minorities as defined by ethnicity, race, sexuality, religion, and so on. The history of the modern state – as Mamdani (Reference Mamdani2020) remarkably reminds us – is the history of political violence, of oppression, of the making of permanent majorities and permanent minorities with catastrophic consequences for the latter. The Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, the Rwandan genocide, the Cambodian genocide, the Bosnian genocide, and the Rohingya genocide are all instances of the perversion of the state apparatus meant to provide ontological – in addition to physical – security for citizens and minorities. Minorities’ clamor for self-determination through independent statehood is almost always more acute when groups feel ontologically insecure. This is particularly the case of the Jews for whom the State of Israel is requisite to evade persecution, oppression, and annihilation in the aftermath of the historically accumulated discrimination that culminated in the Holocaust perpetrated by the Nazis under the auspices of Adolf Hitler. Indeed, the State of Israel is – for most Jewish people – a symbol of ontological security in order to preserve Jewish identity without the burdens of antisemitism. In other words, it is as much about the physical security (survival) of Jews as a people as about the security of Jewish identity. In the next section, I shall expatiate on the constitutive features of Jewish identity based on Jews’ historical narratives of their identity.

Ontological Security, Jewish Nationalism, and Jewish Identity

It is difficult to fix a starting point for Jewish history in large part because “it is not clear what Jewish means exactly and how it relates to or differs from overlapping terms used in the Bible, such as Israelite and Hebrew” (Efron et al. Reference Efron, Weitzman and Lehmann2018, 1). In other words, at various times, Jews have been called different names including Judeans and Judahites so that it is hard to decipher whether these all refer to the same ethnicity or people. What is clear, I think, is that Jews are not a monolithic ethnic group with a single essence as they are internally diverse and spread out across the continents of the world. Notwithstanding Jews’ internal diversity and the problematic of underlining when Jewish history begins, the great Jewish scholar Jacob Neusner (Reference Neusner, Neusner and Avery-Peck2001) divides up the history of the Jewish people into five significant epochs and events. First is the destruction of Jews’ first temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. Second is the destruction of the Jews’ second temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE: this second destruction is the beginning of the Jews’ history as a political entity bounded together by similarity of social and religious experiences even though this did not entail territorial unity for Jewish people. Third is the Muslims’ conquest of the Near and Middle East and North Africa in 640 CE. During this period, Jews in Christendom and Islam were a tolerated, albeit subordinated, minority and the Torah was affirmed as a holy book very like the Koran and the Bible. Not only were the Jews permitted to practice their religion freely, the autonomy of the group was also asserted. Fourth, the American Constitution in 1787 and the French Revolution in 1789 both ensured secularism – that is, the separation of religion from the state – and gave individuals autonomy. This spread throughout the western world. With respect to Jews, it meant that they were given individual rights and lived freely in the west despite occasional persecutions. The final event is the Holocaust and subsequent foundation of the State of Israel on May 15, 1948, after the United Nations’ vote in 1947 to create a Jewish state in Palestine.

Depending upon how you look at it, Jewish history could be best summarized as the history of tensions between ontological security and insecurity for Jews in the diaspora prior to the creation of the State of Israel. Myers (Reference Myers2017, xxvi) defines this in terms of the convergence of two opposing forces: assimilation and antisemitism, where “[a]ssimilation … ensured cultural vitality, allowing Jews to survive for millennia in a variety of settings beyond their homeland. Antisemitism, meanwhile, guaranteed that the path of Jews to full integration was frequently blocked.” The occupations and persecutions did not annihilate the Jewish people, though it engendered their forced displacement and adaptation to other parts of the world including Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa in search of physical security with the hope of returning someday to the land – Eretz Israel (the Land of Israel) – that is central to their cultural identity. The capacity of Jewish people to assimilate in, and quicky adapt to, novel environments despite occasional antisemitic attacks leads Slezkine (Reference Slezkine2004) to call Jews the “Mercurians” of our time.

Collective memories are central to Jewish experiences. These memories are grounded in religion – Judaism. According to the great British sociologist Anthony Smith (Reference Smith1995, 6), “[t]hese [collective] memories have been both local and popular – memories peculiar first of all to the various Israelite tribes and later to each of the scattered Ashkenazi and Sephardi communities – and pan-ethnic and canonical, that is, carried by the basic tenets and practices of Judaism.” Further, these collective memories are central to Jewish nationalism. As he puts it:

Jewish nationalism, then, when it emerged in the third quarter of the nineteenth century in [C]entral and [E]astern Europe, could and did draw on a vast reservoir of collective memories, set down in an ever expanding corpus of religious documents – scriptures, commentaries, law-codes and the like – which together recorded the collective experiences of the scattered Jewish communities in many epochs as well as their origins in the Middle East. As a result, modern Jewry had particularly full and well recorded ethno-histories, replete with rich symbolisms, mythologies, values and traditions, which were widely disseminated to all strata in the many communities of the diaspora, but especially in the Pale of Settlement, the largest concentration of Jews in the nineteenth century. (Smith Reference Smith1995, 6)

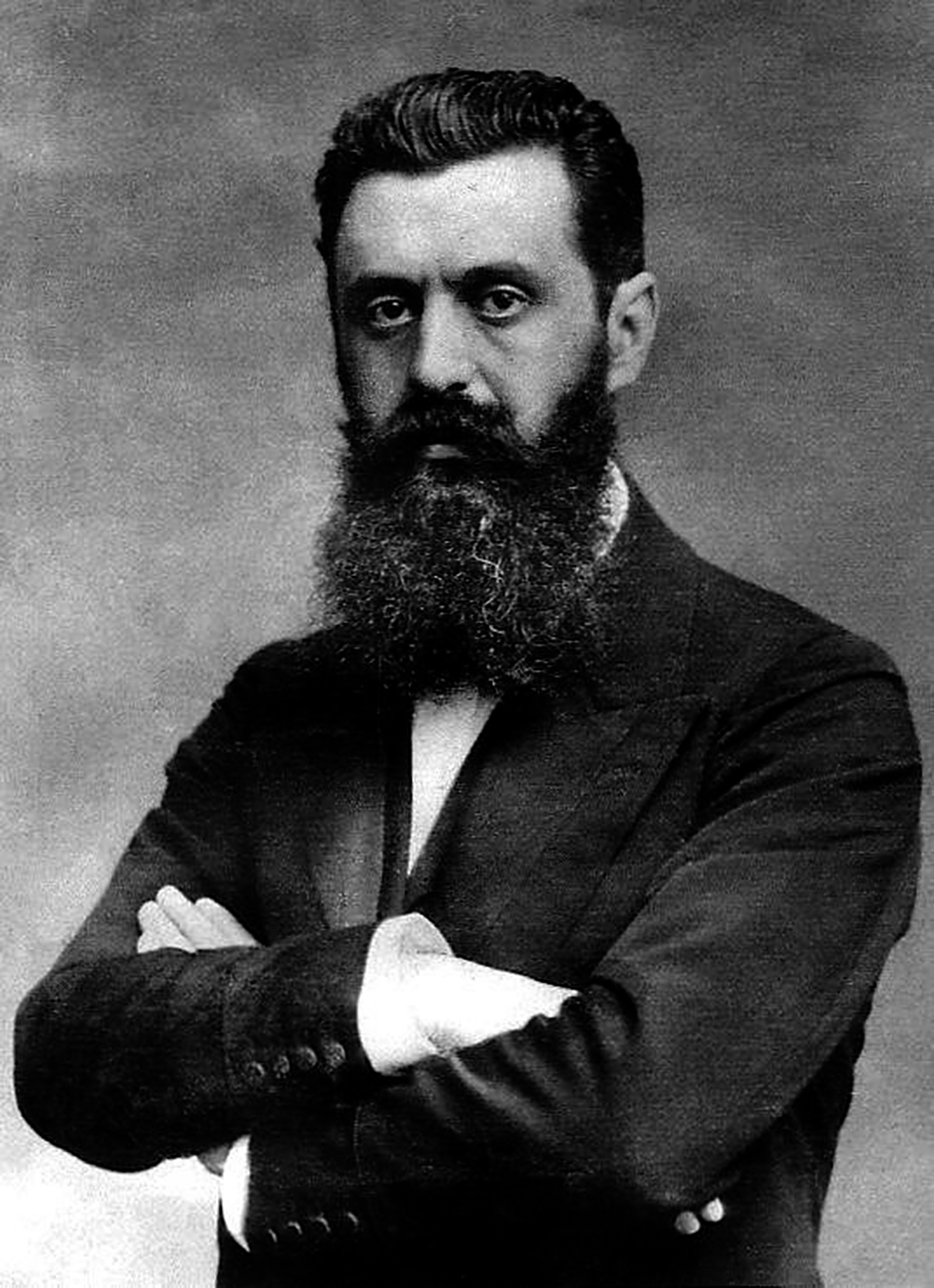

The rise of Jewish nationalism in the nineteenth century in Central and Eastern Europe is the product not just of the collective memories embedded in Judaism but of a conjunction of two other factors: the longstanding hatred of Jews which had made antisemitism ostensibly inevitable (physical security) and the desire for continuity of spiritual, religious, and cultural practices embedded in the Land of Israel for the Jewish diaspora who had been displaced by a series of pogroms, expulsions, and persecutions for eighteen centuries (ontological security). The central argument of antisemites was that Jews cannot be assimilated in European societies no matter how well the Jews are integrated in European societies; Heinrich von Treitschke’s article entitled “The Jews are Our Misfortune” is a paradigmatic example of this. Jewish nationalism – as part of the universal quest for self-determination embedded in nationalism and liberalism in the nineteenth century (Avineri Reference Avineri1981, 4–13) – was antithetical to the prevalent antisemitism that had seen the Jews persecuted in many parts of Europe (see Stillman Reference Stillman2009; Hertzberg Reference Hertzberg1997). The physician Leon Pinsker (Reference Pinsker and Hertzberg1997) wrote that antisemitism – or “Judeophobia” as he termed it – is a clinical disorder, a form of demonopathy that demonizes Judaism and Jews, and that “autoemancipation” is the ultimate solution to the perennial Jewish question in circumstances of uncertainties as to whether Jews can ever be fully integrated in European societies. As Frankel (Reference Frankl2009, 15) puts it: “a direct challenge to the security of the Jews in one country or another could not go unanswered, especially when, as was so often the case, it came in times of peace and relative tranquillity.” Jewish nationalism emerged in several forms in the nineteenth century with different proposals to settle Jews “either in the non-Jewish environment (autonomism), or in a socially reconstituted human milieu (Jewish socialism), or in a separate territory (territorialism), or in the Land of Israel (Zionism), or in a socially reconstituted human environment in the Land of Israel (Socialist Zionism)” (Friesel Reference Friesel2006, 296). The forerunners of Zionism – Zvi Hirsch Kalischer, Moses Hess, Judah Alkalai (see Katz Reference Katz, Reinharz and Shapira1996; Laqueur Reference Laqueur2003) – very like Zionist leaders such as Theodor Herzl (see figure 2), Max Nordau, and Ahad Ha’am all made a case for the creation of a Jewish state not only to protect diasporic Jews from antisemitic attacks but also to provide Jews with opportunity to return to the spiritual home central to their identity. Zionism had not only a political basis but also cultural and religious foundations. It could thus be argued that Zionism emerged from existential anxiety amongst Jews in the diaspora who longed for refuge in the Land of Israel – the cultural, religious, and spiritual home of the Jews.

To illustrate the interaction between physical and ontological security in Jewish nationalism, one needs to look at the disputes between Territorialism and Zionism, two movements and ideologies that emerged in the 1880s. For Territorialists – territorialism was championed by the Jewish Territorial Organisation (ITO) and the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization – like Israel Zangwill the Jewish question must be resolved by establishing an autonomous entity or state for Jews wherever is possible in the world so that the choice should not be limited to the Land of Israel (Alroey Reference Alroey2011, 3; Almagor Reference Almagor2019). The Territorialists were concerned not so much with ontological security but with physical security. Whereas the ITO’s proposals for Jewish settlement under the leadership of Israel Zangwill included places such as Mesopotamia, Ecuador, Cyrenaica (Libya), Angola, and Honduras, the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization under the auspices of Russian social-revolutionary émigré Isaac Steinberg included Australia (the Kimberley Plan), Suriname, Madagascar, French and British Guiana, Madagascar, New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides. By contrast, Zionists were concerned as much about physical security as about ontological security. This is why they insisted that the Jewish state must be founded on the Land of Israel. For Zionists, the Land of Israel is the spiritual center of Jewish people. It embodies the Jewish self: the history, culture, and religious heritage of Jews. According to Avineri (Reference Avineri1981, 3, emphasis in original): “What singled out the Jews from the Christian and Muslim majority communities in whose midst they have resided for two millennia was not only their distinct religious beliefs but also their link – tenuous and nebulous as it might have been – with the distant land of their forefathers. It was because of this that Jews were considered by others – and considered themselves – not only a minority, but a minority in exile.” The idea of reclaiming the historic homeland meant that Zionism went beyond merely resolving Jews’ physical insecurity from antisemitic attacks in Central and Eastern Europe; it was also concerned with the preservation of Jewish identity amidst the forced assimilations and dispersions that unjust treatments had wrought upon Jews for two millennia. Zionists, to put it more bluntly, maintained that Zionism was impossible without Zion. The “negation of the diaspora” – the assumption that Jewish identity is insecure, and Jewish emancipation is unfeasible, in the diaspora – was conducive to the Zionist project of establishing not merely a “State of Jews but a really Jewish State” (Ha’am Reference Ha’am and Hertzberg1997, 267). This pervasive sentiment in Zionism appealed to the ontological security needs of the Jewish diaspora who longed to return to the Land of Israel with the intent of reconnecting with their religious, spiritual, and cultural selves.

If the Land of Israel is inseparable from Jewish identity, so also is the Holocaust. In a poll in 2013 where American Jews were asked what it means to be Jewish, 73% underlined that Holocaust commemoration is essential to their sense of Jewishness (Pew Research Center 2013). Neusner (Reference Neusner, Neusner and Avery-Peck2001) posits that the events of the Holocaust delimited a wholly novel ecology for Jewish people. First, it raised the question of the problem of evil, and second, it redefined the social and political life of the Jews. These radical transformations in Jewish thought and political life must, I think, be explicated. The problem of evil – an age-old philosophical conundrum regarding the (ir)reconcilability of the existence of evil with belief in an omnibenevolent, omniscient, and omnipotent supernatural being called God – in light of the Holocaust means that Jews commenced asking the following question: “where was God in Auschwitz?” In other words, if the good God whom the Jews had venerated and offered prayers to for centuries were alive and active, why did He allow the Jews to face such gruesome extermination by the vicious Nazi regime under the auspices of Adolf Hitler? Kessler (Reference Kessler2007, 51–54) has surveyed some responses to this challenging question: some ultra-Orthodox Jews consider the Holocaust as a punishment for the infidelity or unfaithfulness of Israel; others tend to conceive the Holocaust in instrumental terms in that without it, it would have been impossible to birth the current State of Israel; still others have had their faith shattered in large part because they believe that God deserted Israel – the “chosen people” – when they most needed to be saved from Nazi miscreants. With many Jewish theologians positing the notion of a limited God who is really not in absolute control of the world and others suggesting that God shared in the human suffering the Holocaust portends, there is no lucid consensus as much between Jewish theologians as between ordinary Jews with regard to the apposite interpretation of the gory event that saw the mass extermination of Jews in the European continent.

Regardless of the myriad interpretations of the Holocaust, it is incontrovertible that the State of Israel signifies ontological security for most, if in fact not all, Jewish people. It is little wonder, then, that the State of Israel asserts the right to territorial integrity and control over the Land of Israel – variously termed the Promised Land, the Land of Canaan, or the Holy Land which, according to the Tanakh, was given by God to Abraham and his descendants, Israel – in part because it perceives this as redemptive for the Jewish people in terms of evading annihilation and guaranteeing the survival of Judaism and Jewish cultural life. For, politically, Jews generally hold the view that the existence of the State of Israel is crucial to the physical security of the Jewish people – both for those who have now returned home after many years in exile and for those who, despite being in the diaspora, invariably want to feel the connection to the Land of Israel that is profoundly central to their historical and cultural identity. But the State of Israel is beyond political symbolism; it has a spiritual dimension, too. It is the spiritual connection to the Land of Israel which the State of Israel lays claim to that serves as the foundation of Judaism – the religion of Jews. Rabbi Tony Bayfield has written extensively – albeit from a theological perspective – about Israel as land and people basing his contention on the Jewish scriptures. Bayfield (Reference Bayfield2019) traces the connection of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel in the Book of Genesis where God required Abraham to leave his native land to a different one: based on this biblical narrative, Bayfield regards Judaism as a journey, one that begins with Abraham and continued through to the emergence of Christianity and Islam both of whom acknowledge Abraham’s unwavering faith in God as central to their own religious tenets. The Land of Israel – in Bayfield’s very original imagination – is integral to the religious life of Jewish people, for it is central not only to Jewish daily prayer but also to the Sabbath and festival prayers. Bayfield avers that without the Land of Israel Jews and Judaism would not have survived persecutions for centuries and could not survive today. From this perspective, it is axiomatic that the significance of the State of Israel is tied to its relevance to the practice of Judaism and the persistence of Jewish culture since it enables Jews to live out their Jewish identity devoid of totalitarian tyranny or compulsions to assimilate other cultures to the detriment of Jewish culture. This sentiment has been equally expressed by the Israeli journalist and author Yossi Klein Halevi (Reference Halevi2002) who sees the Land of Israel as central to his profession of the faith everyday as he faces toward Jerusalem to recite his daily prayers: it is such religious and spiritual experience that largely orientates Jewish cultural life.

Despite the common history which Jewish people share, Edward Kessler (Reference Kessler2007) notes that Jews are divided between what is constitutive of Jewish identity – that is, whether being Jewish means association with the State of Israel, the religion (Judaism), or the Jewish culture.Footnote 2 According to Kessler, most Jews consider these three aspects as central to their Jewishness, but some others differ in various ways. For example, ultra-Orthodox Jews identify with the religion (Judaism) but do not support the creation of a Jewish state (because, they argue, it should be created by the Messiah, God’s anointed one), and they do not regard culture, save for religious customs, as central to Jewish experiences. Others – religious Zionists, Observant West Bank Settlers, and secular Israelis – pinpoint the Land of Israel as central to Jewish identity. Still others, like the Secular Diaspora Jews, connect their Jewish identity with the history, ethics, culture, and shared experiences of the Jewish people. Notwithstanding these discrepancies in interpretations of Jewishness, for Jews the State of Israel is intimately connected to ontological security to evade the threats to Jewish culture and religion embedded in the Land of Israel.

It is worth noting that the State of Israel does not possess only a Jewish identity; it, in fact, has multiple identities. Lupovici (Reference Lupovici2012) posits that the State of Israel has three identities that continually need to be ontologically secured: Jewish identity, democratic identity, and security provider. These tripartite identities are challenged at different times in Israel’s continuous engagement with Palestinians. This leads Lupovici (Reference Lupovici2012, 813), with the paradigmatic example of the State of Israel’s responses to the Second Intifada, to advance the theory of “ontological dissonance,” a phenomenon that occurs when “the potential solutions to a collective actor’s (for example, a state’s) various threatened identities – that is, the various ontological insecurities it faces – are in opposition, compelling the actor to choose among contradictory measures.” How can the state’s Jewish identity be reconciled with its democratic identity and its identity as security provider in circumstances of clashes with Palestinian Arabs? How to reconcile the fact that the State of Israel is a Jewish nation based on respect for the principles of Judaism with the cultural, ethnic, and religious heterogeneity of its populations? How can the Israeli state maintain its identity as security provider in its contestations with Palestinians without stripping itself of its democratic and Jewish identities? How can Jewish law which developed under conditions of exile accommodate or fail to accommodate the principle and practice of democratic citizenship? How is democratic pluralism in congruence with traditional Judaism? The State of Israel, as I say, was not established to accommodate heterogeneity, a characteristic of many modern states: multiculturalism was not, as I see it, built into its very fabric. It was established as a unique Jewish state to provide physical and ontological security for Jews with Judaism at its core foundation despite its formally secular status. This explains why Lupovic (Reference Lupovici2012, 822) asserts that

Jewish religious practices have become constitutive of the Israeli ethos, but in a traditionalist (historical nationalist) rather than a religious way. This identity derives from religious sources, making use of religious symbols, practices, and language, but it is fundamentally not religious. In fact, being Jewish may concern the link of an individual to the Jewish people, not just to the religion. Nevertheless, after the 1967 War the Israeli-Jewish identity seems to have become more “Judaic” and less civic, and the “land of Israel” became a more prominent part of the Jewish (national) identity.

The questions I have raised regarding Israel’s myriad identities continually perturb the Israeli state. But they are also conundrums that should apparently trouble any ethnoreligious group that imagines kinship with the Jews and aspires to sovereign statehood for the purposes of curbing perceived discrimination and marginalization, too – namely, the Igbo. In the next section, I tease out the Igbo narrative of Jewish identity derived from the Hamitic hypothesis, focusing on the racialist undertones of the hypothesis and its implausibility in explicating the origins of the Igbo.

The Hamitic Hypothesis and the Construction of Igbo Jewishness

Before delving into the racist origins of the Hamitic hypothesis, I should like to state that the Igbo are one amongst the many ethnic groups in Africa that claim Jewish ancestry. From Ethiopia, Madagascar, Zimbabwe, and South Africa to Cameroon, Ghana, Rwanda, and Nigeria, ethnic groups in Africa increasingly claim Jewish descent (Kaplan Reference Kaplan1999; Bruder Reference Bruder2008; Bruder and Parfitt Reference Bruder and Parfitt2012; Parfitt Reference Parfitt2013; Lis Reference Lis2015; Lis, Miles, and Parfitt Reference Lis, William and Parfitt2016; Devir Reference Devir2017; Gidron Reference Gidron2021). Miles (Reference Miles2019) divides emerging Jewish movements in Africa into three different categories: vague Israelitism, Hebraic eclecticism, and orthopraxis. The vague Israelitism is characterized by belief in Israelite ethnogenesis, the invocation of cultural and linguistic similarities with Hebrew, and the linkage of local experiences of oppression to the Holocaust. Hebraic eclecticism is characterized by the mixing of local cultural practices and Christian rituals with Jewish religious customs and the Judaizing of non-Jewish rituals and dogma. Finally, orthopraxis is characterized by strict adherence to the principles and practices of “normative Judaism” in terms of the observance of Jewish holidays and dietary laws, the study of the Torah and the Hebrew language, and so forth. The “Igbo Jews” fall into these three different categories. This is axiomatic from Bruder’s (Reference Bruder, Bruder and Parfitt2012, 31) categorization which divides the Igbo into three groups:

[T]he Hebrewists, who consider themselves as “pre-Talmudic” Jews on the basis of the alleged Hebraic traditions of their forefathers; the members of the various recent Jewish congregations, who have been striving toward Jewish recognition for some years; and, finally, the somewhat different Sabbatherians, who number more than two million and who practice a kind of Judaism while also reading the New Testament.

What binds together all the ethnic groups in the African continent – including the Igbos – that claim a Jewish heritage or Jewishness is undoubtedly the Hamitic hypothesis, an age-old racialist discourse which states that “everything of value ever found in Africa was brought there by the Hamites, allegedly a branch of the Caucasian race” (Sanders Reference Sanders1969, 521; Zachernuk Reference Zachernuk1994, 428–429; see also Seligman Reference Seligman1930). The Hamitic hypothesis derives from a biblical story in Genesis where Noah cursed Ham’s son Canaan.Footnote 3 Although the original biblical account does not make any reference to racial differences in its discussion of Noah’s sons – Shem, Ham, and Japhet – the association of Ham’s curse with blackness and Ham’s progeny as degenerate black people first appeared in the Babylonian Talmud, a collection of Jewish oral traditions, in the sixth century. The idea of associating the Hamites with blackness persisted through the Middle Ages and was generally accepted by the year 1600. Indeed, by the sixteenth century, Africa became the place of the descendants of Ham and Western interventions in the continent were based on two broad assumptions: first, that black people were too degenerate to fashion their own history, and second, that black people were – as a consequence of their supposed degeneracy – incapable of having their own history (Parfitt Reference Parfitt2013, 25). Once the Hamitic hypothesis was tied to economic gain, it was consequently employed as a moral, ethical, and ideological basis to contend that black people are naturally inferior to white Europeans and should be enslaved for economic purposes. For the idea that “blackness was an immediate consequence of the curse, that all blacks were born into slavery, and that all blacks descended from Ham was a useful pro-slavery argument” (Parfitt Reference Parfitt2013, 28). In other words, the Hamitic hypothesis not only coincided with black slavery, it was also used to justify the unconscionable immoral practice. As Sanders (Reference Sanders1969, 523) puts it:

On the one hand, it [the Hamitic hypothesis] allowed exploitation of the Negro for economic gain to remain undisturbed by any Christian doubts as to the moral issues involved. “A servant of servants shall he be” clearly meant that the Negro was preordained for slavery. Neither individual nor collective guilt was to be borne for a state of the world created by the Almighty. On the other hand, Christian cosmology could remain at peace, because identifying the Negro as a Hamite – thus as a brother – kept him in the family of man in accordance with the biblical story of the creation of mankind.

It is in the milieu of the preponderance of the Hamitic hypothesis in the colonial epoch that “Judaised” Africans that Olaudah Equiano wrote his Interesting Narrative – the first known account to compare the Jews with the Igbo in West Africa. Equiano’s narrative forms part of colonial discourse; for, “[g]iven the widespread nature of the colonial theories maintaining that there were Israelite Lost Tribes in every spot on the globe, from the Americas to the islands of the Pacific, the London-based Equiano would have been hard- pressed not to be aware of them” (Parfitt Reference Parfitt2013, 40–41). In Equiano’s (Reference Equiano1999, 18) autobiography wherein he recounts his experience of the Atlantic slave trade and of his spiritual redemption, he compares the customs and practices of the Igbo society of his time to those of the Jewish people:

We practiced circumcision like the Jews, and made offerings and feasts on that occasion in the same manner as they did. Like them also, our children were named from some event, some circumstance, or fancied foreboding at the time of their birth … . I have before remarked that the natives of this part of Africa are extremely cleanly. This necessary habit of decency was with us a part of religion, and therefore we had many purifications and washings; indeed almost as many, and used on the same occasions, if my recollection does not fail me, as the Jews.

In a different passage, Equiano underscores cultural similarities between the Jews and the Igbo. Indeed, not only does he believe the differences in color between the Igbo and Jews are due to evolutionary climatic conditions but also that there are significant similarities in government, law, and cultural practices between the two ethnic groups:

Like the Israelites in their primitive state, our government was conducted by our chiefs or judges, our wisemen, and elders; and the head of a family, with us, enjoyed a similar authority over his household with that which is ascribed to Abraham and the other Patriarchs. The law of retaliation prevailed almost universally with us as with them: and even their religion appeared to have shed upon us a ray of its glory, though broken and spent in its passage, or eclipsed by the cloud with which time, tradition, and ignorance might have enveloped it. For we had our circumcision (a rite, I believe, peculiar to that people): we had also our sacrifices and burnt-offerings, our washings and purifications, on the same occasions as they had. (Equiano Reference Equiano1999, 21)

As I have already underlined in the introduction, Equiano made these comparisons with Jews in order to “give added credibility to his work by invoking this, the conventional wisdom of his time, namely that there were Jews in [W]est Africa, and to give the impression that black Africans were civilized and humane and had a culture that, like British culture and European culture in general, had been influenced by Judaic ideals” (Parfitt Reference Parfitt2013, 41). Equiano’s idea of the Jewishness of the Igbo was further popularized by G. T. Basden – a British missionary who had served and lived in Igboland for about thirty-five years. According to Basden (Reference Basden1921, 31), in Igbo cultural practices, “[t]here are certain customs which rather point to Levitic influence at a more or less remote period. This is suggested in the underlying ideas concerning sacrifice and in the practice of circumcision. The language also bears several interesting parallels with the Hebrew idiom.” Basden’s detailed ethnographic account of Igbo village communities helped to solidify the assumption that Igbos are Jews.

Although Equiano’s use of the Hamitic hypothesis to contest the enslavement of black people in the heydays of slavery is absolutely remarkable, his claim that certain rituals and cultural practices are peculiar to Jews and Igbos is, I think, quite misguided. Take, for instance, Equiano’s supposition that names in the Igbo tradition as in the Jewish tradition almost always reflect some circumstance or event. He describes his case: “I was named Olaudah, which, in our language signifies ‘vicissitudes or fortunate,’ also, ‘one favoured, and having a loud voice and well spoken” (Equiano Reference Equiano1999, 18). Whilst it is interesting that he could compare the naming tradition of both groups, such cultural practice is neither peculiar to Igbos nor to Jews. Indeed, there are numerous groups within and beyond Africa for whom names and naming are not entirely arbitrary but embedded in cultural symbolism. Describing naming traditions in Africa, the eminent African theologian Mbiti (Reference Mbiti1969, 154) explicates that

Nearly all African names have a meaning. The naming of children is therefore an important occasion which is often marked by ceremonies in many societies. Some names may mark the occasion of the child’s birth. For example, if the birth occurs during rain, the child would be given a name which means “Rain,” or “Rainy,” or “Water”; if the mother is on a journey at the time, the child might be called “Traveller,” “Stranger,” “Road” or “Wanderer”; if there is a locust invasion when the child is born, it might be called “Locust,” or “Famine,” or “Pain.” Some names describe the personality of the individual, or his character, or some key events in his life. There is no stop to the giving of names in many African societies, so that a person can acquire a sizeable collection of names by the time he becomes an old man. Other names given to children may come from the living-dead who might be thought to have been partially “re-incarnated” in the child, especially if the family observes certain traits in common between the child and a particular living-dead. In some societies it is also the custom to give the names of the grandparents to the children. The name is the person, and many names are often descriptive of the individual, particularly names acquired as the person grows.

A classic naming tradition in Africa – to buttress Mbiti’s argument – is that of the Akan which reflects the days in which a child is born. Names according to the particular day of birth include Kwadwo (Monday), Kwabena (Tuesday), Kwaku (Wednesday), Yaw (Thursday), Kofi (Friday), Kwame (Saturday), and Akwasi (Sunday). A male Saturday-born is called “Kwame” so that anyone who bears that name – the former president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, or the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, say – is automatically assumed to have been born on a Saturday. Additionally, in the Akan tradition, it is believed that people born on particular days possess certain attributes. For example, it is believed that a person who bears the name “Kwame” radiates good fortune and health – and males who bear the name are typically considered as intelligent and talented problem solvers. There are also names for twins, birth order, and special delivery of children. In the latter case, names are given according to whether children are delivered under special circumstances, and this could be whether they are born on the field (Efum) or premature (Nyaméama) or under happy circumstances (Afriyie) amongst numerous possibilities. Beyond the Akan naming tradition – and dare I say, beyond Africa – there are countless cultures (ancient and modern) with traditions that associate names with particular events, attributes, and circumstances so that to suppose, as Equiano and other theorists of the Hamitic hypothesis do, that there are cultural similarities unique to Igbos and Jews is anthropologically implausible.

But there is a substantial reason for why the Hamitic hypothesis is utterly misguided: the fact that this hypothesis is believed to be true by racists, anti-racists, nationalists, and cosmopolitans for varied purposes is not sufficient reason to suppose it is true. We cannot rely on Equiano’s account because it was based on received ideas in the west where he lived out his adult years and was largely influenced by insights from Christian authors in the west regarding Jewish customs which he himself underlined in his autobiography. To begin with, as I say, there is neither archaeological nor historical evidence to support the claim that the Igbos are one of the lost tribes of Israel in Africa or that they have a Semitic heritage. Chuku (Reference Chuku2018, 4) contends that “[t]he Hamitic theorists have ignored the importance of the corroborative use of multiple sources – oral traditions, archaeological, and linguistic evidence – in dealing with complex and complicated historical topics such as origins, migrations, and settlements. Incidentally, none of these multiple sources has supported that the Igbo originated either from ancient Egypt or the Middle East.” Similarly, regarding the falsity of the Hamitic hypothesis, the Igbo historian Adiele Afigbo (Reference Afigbo1983, 3) argues that “[n]ot only is there no concrete evidence in its support, but it is in conflict with what archaeological and linguistic evidence we do have.” Through historical linguistics we now know that the “Igbo language belongs to the Kwa subfamily of the larger Niger-Congo language family; glottochronology points to a point in time about 6,000 years ago when Igbo separated from proto-Kwa, assumed to be spoken in the Niger-Benue confluence area” (Harneit-Sievers Reference Harneit-Sievers2006, 19). And archaeologists and historians have discovered copious evidence of technology, farming, and trade in Igboland since 1000 BCE which disprove the Hamitic hypothesis (Isichei Reference Isichei1977; Oriji Reference Oriji1990; Harneit-Sievers Reference Harneit-Sievers2006). This implies that the Jews and Igbos are distinct groups with dissimilar histories, territorial settlements, and migration patterns. The Jews’ persecutions by Babylonians, Romans, and Nazis are not part of the historical narrative of Igbo people. The Zionist’s appeal to the Land of Israel as constitutive of Jewishness and the unwavering desire to return there is not part of the historical consciousness of the Igbo. This is precisely why, when asked whether there are similarities between the Jewish situation and that of the Igbo in terms of national consciousness during the Nigerian Civil War, Achebe (Reference Achebe1968, 36) contends that there is hardly any connection between the Jewish experience and the plight of the Igbo: for whereas the Jews were dispersed from their original home in the Land of Israel and always longed to return there, there was no dispersion or perennial longing to return home (in southeast Nigeria) for the Igbos. Classical and Modern Hebrew are not in the same language family as the Igbo language. However, the fact that the Hamitic hypothesis is erroneous in explaining the origins of the Igbo does not mean that it has no social power. Rather, the hypothesis has fundamentally attained the status of an origin myth amongst Igbos and used not only to comprehend but also to interpret and explain the state of affairs in postcolonial Nigeria.

If the Hamitic hypothesis which postulates the Semitic origin of the Igbo is, so to speak, an “invented tradition” (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger2012), so also is Igbo identity or Igboness which did not exist in precolonial Igboland. In precolonial times, the term “Igbo” was never used by the Igbo in reference to themselves as they were not a monolithic group but many different polities that did not – prior to colonialism – consider themselves one identity group. Igbo societies are often described as “segmentary” and “acephalous” though this has been countered by some scholars who contend that some like the Aro had chiefs and were not headless (Nwokeji Reference Nwokeji2010). Harneit-Sievers (Reference Harneit-Sievers2006, 112–113) avers that “[t]here was no Igbo ethnic identity in precolonial Igboland. The term ‘Igbo’ was applied locally to denote ‘others,’ ‘strangers,’ or ‘slaves,’ but it appears to have not been used as a self-designator, and certainly not to denote any larger group that included one’s own community.”Footnote 4 It would be an oversimplification, I think, to suppose that Igbo societies were – or are – internally homogeneous. In the past as well as in the present, the Igbo have never been a homogeneous ethnic group: there are as many dialectical variations as there are diverse customs and practices within Igbo societies. The various autonomous villages and communities that now constitute Igboland gradually accepted the designation of “Igbo” under colonial rule – especially in the 1950s when “the inhabitants of rural Igbo villages began to consider themselves as being Igbo” (Bruder Reference Bruder, Bruder and Parfitt2012, 38) – after they became aware of some cultural similarities amongst them. The unification of different Igbo societies as well as the formation and ossification of something called an “Igbo identity” is due to the work of colonizers, Christian missionaries, social anthropologists, Igbo cultural nationalists, urban migration, and anti-Igbo prejudices from interactions with non-Igbo ethnic groups (Harneit-Sievers Reference Harneit-Sievers2006; Bruder Reference Bruder, Bruder and Parfitt2012, 44–46). Theorists of social identity are agreed on the fact that social identities – ethnicity, religion, race, say – are dialogically constructed: identity is created as much by difference as by similarity (see Appiah Reference Appiah2005, 62–113; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2008). Applied to the Nigerian context, one could contend that Igbo identity is virtually impossible to grasp devoid of the presence of other identity groups such as the Hausa, the Fulani, and the Yoruba, amongst over three hundred other ethnic groups in Nigeria. In the absence of a common culture, language, and past amongst Igbo societies, the Hamitic hypothesis was appropriated by Igbos to fashion a shared history and identity that would enable them to extirpate the vestiges of colonialism. This is why Bruder (Reference Bruder, Bruder and Parfitt2012, 43) asserts that – with exposure of Igbos to Jewish experiences in the Bible, owing to the work of Christian missionaries – “[t]he colonised Igbo believed themselves to be the oppressed Hebrews of the Bible and projected their own lives into the narratives of Israel’s formative history.” Over time, Igbos have internalized the Hamitic hypothesis, reworked it, and employed it to make sense of their sociopolitical situation with the view to transform what they consider the deplorable state of affairs in postcolonial Nigeria. As Bruder (Reference Bruder, Bruder and Parfitt2012, 56) notably puts it, “In the Nigeria[n] State marked by post-colonialism upheavals, political ethnic conflicts, and economic uncertainty, the adoption of Jewish identities has been magnified as a coherent prospect and indicates various attempts by [the] Igbo to seek change at a cosmic, social, and supraindividual level through the restoration of a real or imagined past religious order.” Jewishness is therefore posited as the pristine Igbo identity.

When Equiano drew connections between Igbos and Jews in 1789, he absolutely had no idea of Biafra, nor did he intend the creation of the Republic of Biafra. Indeed, in his days, Jews and Igbos had no state of their own nor was there any lucid indication that they wished to create one. Put simply, Equiano had no nationalist agenda. Rather, his intention was to emphasize the humanity of black people and of the place where he was born in Africa prior to being taken captive and sold off to European slavers. Jewish nationalism and Igbo nationalism were practically non-existent in Equiano’s time. By connecting his narrative of Igbo cultural life to Jewish customs with copious amounts of citations from Christian theologians in his day to back his contention, Equiano could make a case against slavery as an abjection that subjugated human beings to unjustified cruelty. As we shall see, however, when Igbo nationalists started to forcefully invoke the Jewish connection beginning during the Nigerian Civil War – the apotheosis, in my view, of Igbo nationalism – they did not imitate Equiano to argue only for the similarity of customs between Jews and Igbos but also for the similarity of experiences of ethnoreligious deprivation and discrimination. For what Igbo nationalists saw in the Jewish narrative of identity that they could appropriate is the Jewish experience of the Nazi Holocaust with which they could make the case that Igbos were similarly at risk of extermination in consequence of their ethnoreligious difference in a state dominated by northern Muslims. This fear provoked existential anxiety within the Igbo society regarding their ontological security. Analogical reasoning served to recreate a novel Igbo identity based on shared experiences of discrimination and to attract international attention requisite for the nationalist project of self-determination. In the section that follows, then, I shall demonstrate the strategic appropriation of Jewishness by Igbo nationalists during the Nigerian Civil War.

Ontological (In)Security and the Social Power of Analogizing Jewishness

Prior to British colonialization of Nigeria that began after the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s, present-day Nigeria was just a combination of diverse ethnic groups inhabiting different territories. Put differently, Nigerians did not see themselves as “Nigerians.” The formation of what we could call a “pan-Nigerian identity” began in 1914 when the two protectorates of Nigeria – the Southern Nigeria Protectorate and the Northern Nigeria Protectorate – were amalgamated to balance the budget deficit of the northern region (Agbiboa Reference Agbiboa2013; Falola and Heaton Reference Falola and Heaton2008).Footnote 5 But the amalgamation of the two protectorates with extremely diverse ethnic groups – over three hundred of them – created what Ekeh (Reference Ekeh1975, 92) terms the “two publics”: in one public realm (primordial public) are “primordial groupings, ties, and sentiment” and in the other (civic public) are “military, the civil service, the police.” These two, Ekeh contends, have a dialectical relationship in postcolonial states such as Nigeria as ethnic affiliations interact with, and influence, public institutions.Footnote 6 Beginning in 1945, the incongruous publics engendered conflicts between different ethnicities in the northern region. For example, in 1945 there was a riot orchestrated by the Hausa against the Igbo in Jos (see Plotnicov Reference Plotnicov1971). Similar attacks by northerners against the Igbo living in northern Nigeria occurred in 1953. The fear of domination – that is, the fear of northerners that southerners had an ulterior motive to dominate the center and vice versa – led northerners to institute the “Northernisation policy” in 1954 which “aimed to reduce the [northern] region’s reliance on southern civil servants and professionals by expanding educational opportunities for northerners and curtailing employment of southerners, often by replacing them with more expensive expatriates while northerners received training” (Anthony Reference Anthony2010, 48). This did not sit well with southerners – especially the highly educated Igbo people – who felt that northerners sacrificed merit on the altar of ethnic and regional prejudices.

When Nigeria achieved independence from Britain in 1960, the two publics were not extirpated but instead were integrated into the new state, leading to fierce competition for political power amongst political elites from the three major ethnic groups: the Hausa and Fulani (concentrated in the northern region), the Igbo (concentrated in the southeastern region), and the Yoruba (concentrated in the southwestern region). Indeed, “[t]hese fears of ‘domination’ clouded any sense of national unity in Nigeria in the 1960s, as residents in each region increasingly came to fear that other regions intended to use the political system to enrich themselves at the expense of their Nigerian ‘brothers’ in other regions” (Falola and Heaton Reference Falola and Heaton2008, 165). The consequences of such fears were electoral fraud, thuggery, ethnic baiting, and political corruption. With the political scene bedevilled by fears of ethnic and regional domination, it would take a coup by mainly Igbo military officers and a countercoup by mainly northern military officers in 1966 to officially usher in ethnic bigotry on a large scale throughout the federation. The suspicion by northerners that Igbos harbored an ulterior motive of dominating the entire polity provoked anti-Igbo sentiments in the northern region where many Igbos had established businesses and worked in the civil service (Daly Reference Daly2020, 40–41). The suspicion by northerners that Igbos harboured an ulterior motive of dominating the entire polity provoked anti-Igbo sentiments in the northern region where many Igbos had established businesses and worked in the civil service (Daly Reference Daly2020, 40–41). This was worsened by the fact that the 1966 Nigerian coup d’état was engineered by mostly Igbo soldiers which led to the coup being dubbed, however wrongly, “the Igbo coup.”Footnote 7 This seemingly imbued Nigerian politics with ethnic coloration. So problematic were interethnic relations that there was an anti-Igbo pogrom perpetrated by northerners in various parts of northern Nigeria between May and September 1966 – just six years after Nigeria’s independence – that left over thirty thousand Igbos dead. The historian Samuel Fury Childs Daly describes the anti-Igbo pogrom in 1966 in the following way:

Over the space of three months, tens of thousands of Igbos were killed in northern towns and cities. Isolated instances of anti-Igbo violence also happened outside of the north, including in Lagos. Some, like the killing of civilians by a gang of soldiers outside a barracks in Apapa, were investigated in the moment but most were not. The violence did not take place evenly and the degree to which it was directed by state and military officials varied from place to place. In some towns, it was directed by members of the police or the military. In others, there were individual acts of violence by private citizens but “no consistent pattern of revolt against command” by soldiers … . (Daly Reference Daly2020, 38)

The anti-Igbo pogrom of 1966 led to thousands of Igbos in the northern region fleeing to the Eastern Region – where their ancestral homeland is located – in order to evade persecution from northerners. After a series of failed negotiations between the Federal Military Government (represented by Yakubu Gowon) and the Eastern Region (represented by Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu), the Eastern Region was declared an independent state called the Republic of Biafra on May 30, 1967 by Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu. The declaration of independence of the Republic of Biafra plunged Nigeria into a civil war which occurred between 1967 and 1970. Over a million Igbos were massacred and starved to death by the Nigerian military forces with the support of foreign powers – especially Britain and the Soviet Union – during the civil war (Korieh Reference Korieh2013). As the conflict progressed, images of “Biafran Babies” came to symbolize everything that was wrong with the uncivil violence.