The Mediterranean monk seal Monachus monachus is categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List, with a total of 600–700 individuals in three known subpopulations distributed across the eastern Atlantic and the eastern Mediterranean coasts (Karamanlidis & Dendrinos, Reference Karamanlidis and Dendrinos2015). The largest subpopulation in the eastern Mediterranean comprises 350–450 individuals (Karamanlidis et al., Reference Karamanlidis, Adamantopoulou, Tounta and Dendrinos2019). Approximately 100 of these are in the coastal waters of Turkey (Güçlüsoy et al., Reference Güçlüsoy, Kıraç, Veryeri and Savaş2004), 14 in north-west and southern Cyprus (Nicolaou et al., Reference Nicolaou, Dendrinos, Marcou, Michaelides and Karamanlidis2019) and seven in northern Cyprus (Beton et al., Reference Beton, Broderick, Godley, Kolaç, Ok and Snape2021). The species is subject to multiple anthropogenic threats, including deliberate killings and the entanglement of subadults in fishing nets. However, the most significant threats to monk seals in the eastern Mediterranean are habitat deterioration, destruction and fragmentation (Karamanlidis et al., Reference Karamanlidis, Adamantopoulou, Tounta and Dendrinos2019).

Suitable marine cave habitats are essential for monk seals to haul out and rest or raise pups. Here we investigate the provision of artificial habitat for monk seals. There have been trials of a similar approach for other species: e.g. nest-boxes for the European roller Coracias garrulus (Monti et al., Reference Monti, Nelli, Catoni and Dell'Omo2019), nesting platforms for the white stork Ciconia ciconia (Döndüren, Reference Döndüren2015) and man-made snowdrifts for Saimaa ringed seals Phoca hispida saimensis (Auttila, Reference Auttila2015).

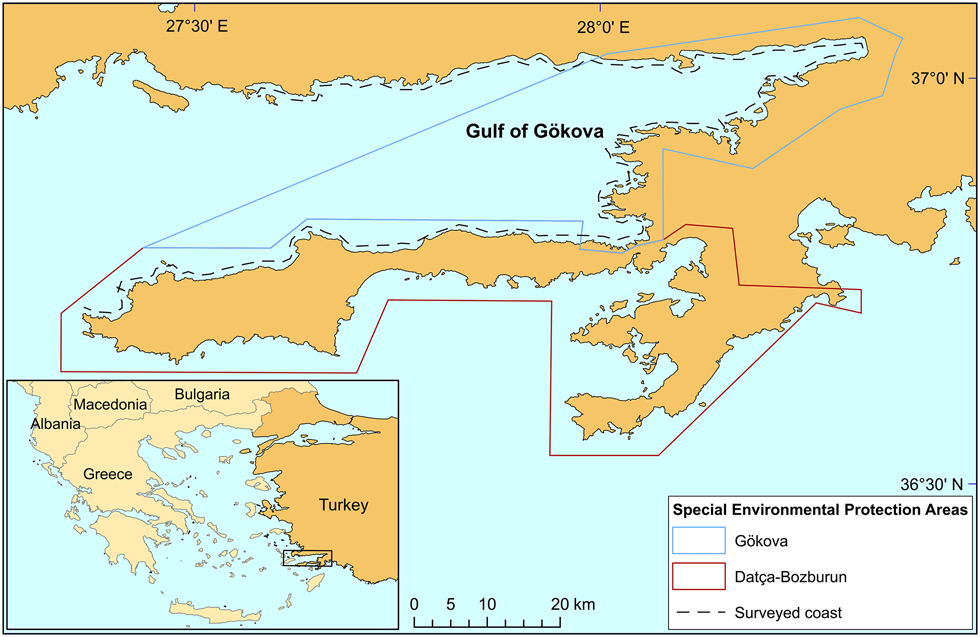

Gökova Bay in the eastern Aegean Sea, on the south-west Mediterranean coast of Turkey (Fig. 1) has a marine area of 1,851 km2, with diverse marine habitats important for multiple species (Ünal et al., Reference Ünal, Kizilkaya and Yildirim2015). It comprises both Gökova and Datça-Bozburun Special Environmental Protection Areas (Güçlüsoy, Reference Güçlüsoy, Katağan, Tokaç, Beşiktepe and Öztürk2015). Datça-Bozburun consists of two peninsulas, Reşadiye (Datça) Peninsula and Bozburun Peninsula, and with a total marine area of 737 km2 it is the largest Special Environmental Protection Area in the Turkish Mediterranean Sea (Güçlüsoy, Reference Güçlüsoy, Katağan, Tokaç, Beşiktepe and Öztürk2015). Prior to this study, there had been no camera-trap monitoring of Mediterranean monk seals in Gökova Bay.

Fig. 1 The location of the Gökova and Datça-Bozburun Special Environmental Protection Areas in the eastern Mediterranean, and the 322 km length of coastal area Gökova Bay surveyed. The exact locations of the caves mentioned in this article are not provided, for the security of the species.

During 2016–2017 we surveyed Mediterranean monk seal habitat along most of Gökova Bay's 322 km coastline (Saydam & Güçlüsoy, Reference Saydam and Güçlüsoy2019), and interviewed local fishers and sailors to identify the locations of any marine caves potentially suitable for Mediterranean monk seals to breed and rest. We examined potential caves by snorkelling (Karamanlidis et al., Reference Karamanlidis, Pires, Silva and Neves2004; Dendrinos et al., Reference Dendrinos, Karamanlidis, Kotomatas, Legakis, Tounta and Matthiopoulos2007), and we installed camera traps in the four suitable caves located.

In October 2017, we discovered one marine cave without a dry ledge that was otherwise suitable for seals and could potentially provide protection from inclement weather. An area within the cave suitable for the construction of an artificial ledge, at the end of the cave (Fig. 2, Plate 1a), did not have any marine habitat formations that would require the cave to be otherwise protected (Öztürk, Reference Öztürk2019). We constructed the artificial ledge during 22–24 June and 20 July 2019. The final level of the ledge was designed to be 10 cm above sea level during high tide, to keep the ledge dry in rough weather.

Fig. 2 The dimensions of the marine cave in which the ledge was constructed (Plate 1).

Plate 1 (a) The cave (Fig. 2) prior to construction of the dry ledge, (b) following construction of the ledge, and (c) a juvenile monk seal Monachus monachus using the ledge.

Jute sacks, with a volume of c. 27 l, filled with a sand and cement mixture at a ratio of c. 350 kg of pozzolanic cement (TS EN 197-1 CEM IV/B (P) 32.5 N) to 1 m3 gravelly sand, boulders and crushed stone were transferred by truck to a loading point 11 km from the cave. We transported all materials on an 8.5 m fishing boat to the cave entrance. The boulders weighing 10–25 kg each, and crushed stone, were transferred in a rigid inflatable boat to the opening of the narrow chamber of the cave and then moved in large buckets or by hand. The boulders (filling a total area of 4 m3) were laid as the foundation and 300 kg of crushed stone was used to fill the spaces between them. The jute sacks were then transported from the fishing boat by a canoe to the ledge location, to keep them dry. A total of 120 jute sacks were laid on the foundation, to become wet and thus for the sand and cement mixture to set (Plate 1b).

During 24 June 2019–17 September 2020 we monitored the cave using a camera trap, visiting once every 2 months to download any recordings and replace batteries. The camera was set in hybrid-mode, to take three consecutive photographs and a 15-s video for each trigger. The recordings from the 405 events were analysed to determine any use of the cave by seals, and the purpose (resting and/or pupping), frequency of use, and to identify the sex and age group of any seals (Samaranch & González, Reference Samaranch and González2000).

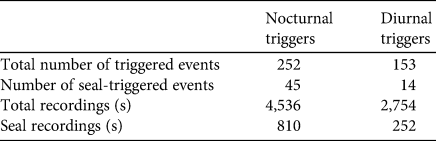

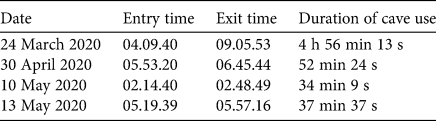

The recordings revealed that a monk seal first used the artificial ledge 8 months after construction (Table 1, Plate 1c) and on three additional occasions (Table 2), with the longest stay nearly 5 h. Its size, inferred relative to the dimension of the jute sacks, and morphology indicated it was a juvenile. It mostly used the cave nocturnally (Table 1). The proximity of other caves suitable for seals in Gökova Bay (c. 20 km and 84 km away) may have contributed to the discoverability of the ledge by monk seals.

Table 1 Details of the camera-trap recordings from the cave (Figs 1 & 2, Plate 1) in which we constructed a ledge for the monk seal Monachus monachus. Each event comprises three images (taken at 1-s intervals) and one 15-s video.

Table 2 Details of the use of the marine cave by a juvenile monk seal.

This intervention was the first construction of an artificial dry ledge in a marine cave for Mediterranean monk seals, and the first to provide evidence that such a ledge can be discovered and used by a seal. As habitat loss and degradation are the most significant threats to this species, increasing the number of potential cave habitats for resting and/or pupping by improving cave structure could potentially be an important method for the conservation and protection of this species. However, consideration of impacts on existing habitats (e.g. those of sessile invertebrates inside caves), alongside discussions with monk seal experts, responsible governmental agencies and any local stakeholders, is essential. The use of this artificial ledge by an Endangered Mediterranean monk seal contributes potentially important information to support future conservation of the species. Future monitoring should determine the suitability of this artificial habitat for pupping, which is key to supporting monk seal populations. We continue to monitor this cave by camera trap.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues and volunteers with the Mediterranean Conservation Society for their collaboration during this study, Gabriella Church and Katy Walker of Fauna & Flora International for their comments, and the Prince Bernhard Nature Fund, Fauna & Flora International and the Endangered Landscapes Programme, which is managed by the Cambridge Conservation Initiative and funded by Arcadia, a charitable trust of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin, for their support.

Author contributions

Ledge design: ES, ZAK; monitoring design: all authors; fieldwork: ES, ZAK; data analysis, writing: ES, HG.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. The permit for ledge construction and monitoring was provided by the Turkish Ministry of Environment and Urbanization (24 May 2019, 70879856-250-E.117731).