PROLOGUE

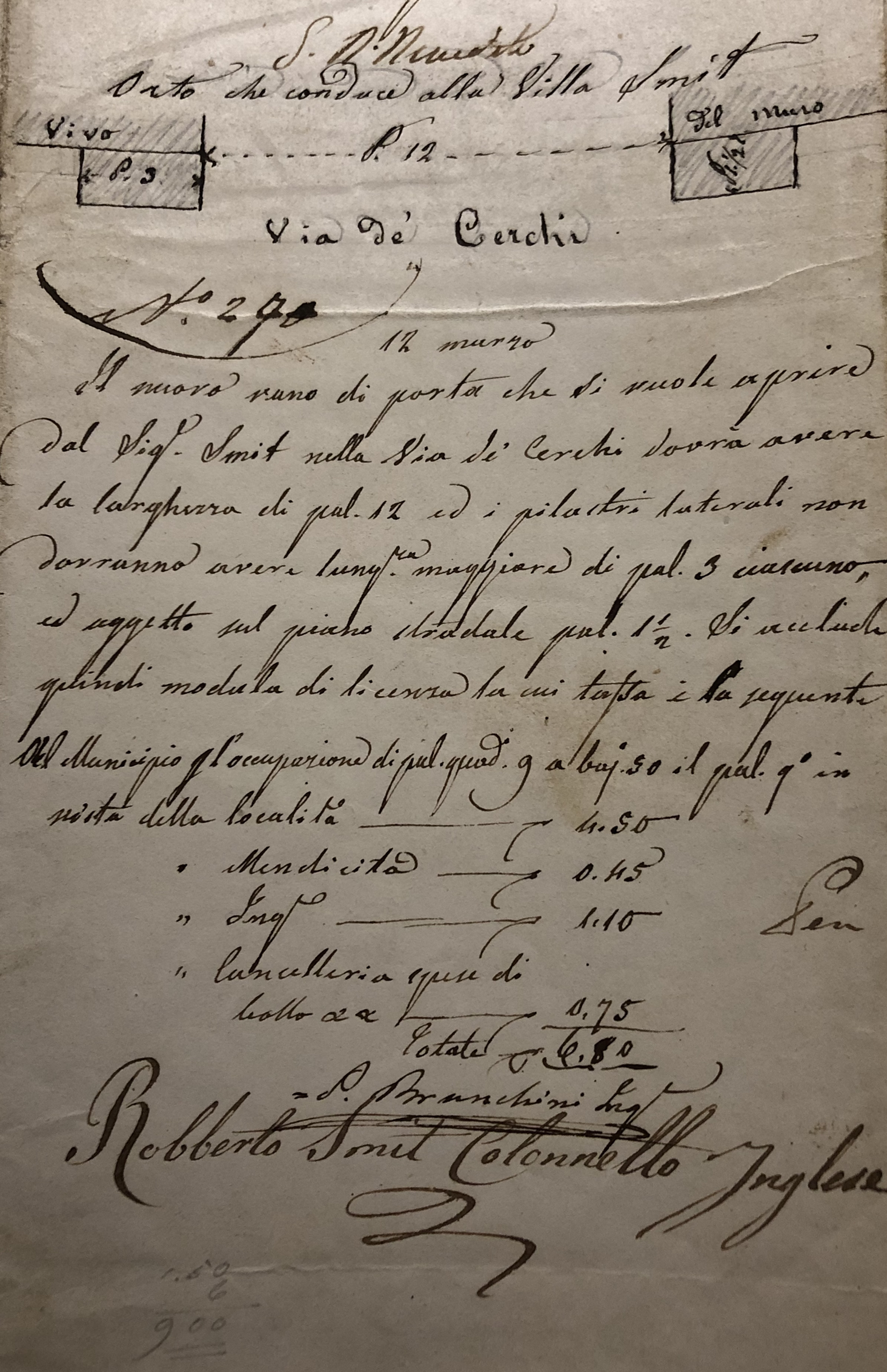

A photographic print on card in the Parker Collection of the Photographic Archive of the British School at Rome, dated between 1864 and 1866, offers a view of the Palatine Hill from via dei Cerchi, in the area of the Circo Massimo (Fig. 1). In the background, the southern slope of the hill leads to the ruins of the Palatine Stadium (to the left) and the Palace of Severus (to the right). In the foreground, a curious iron gate with two solid pillars, enriched by roundels and crowned with delicate pine-cone finials, interrupts a modest boundary wall. A manuscript conserved in the Archivio Storico Capitolino attests that, on 24 March 1851, under the instructions of the engineer G. Palazzi, the City Council of Rome granted a ‘Robberto Smit [sic]’ the licence to open a gate in via dei Cerchi 46.Footnote 2 By locating the street number in the urban cadastre (official property register) of Rome (1871) — where ‘46’ appears as a correction in pencil over a ‘45’ — it is possible to suggest that the photographic print shows the gate wanted by Smith at the foot of the hill (Fig. 2). The argument is strengthened by a visual comparison between the albumen and a small sketch plan of the project proposal, which is dated 12 March 1851 (Fig. 3). This plan shows the outline of the wall and two pillars, and their positioning in between via dei Cerchi and the ‘Garden that introduces to Villa Smit [sic]’ (‘Orto che conduce alla Villa Smit [sic]’).

Fig. 1. The gate of Villa Smith in via dei Cerchi, Rome. John Henry Parker (1806–1884), Palatine, between 1864 and 1866, photographic print on card, image 19 × 26, on card 22 × 30 cm. Rome, BSR PA, John Henry Parker Collection, jhp-0108. Courtesy of the British School at Rome.

Fig. 2. Detail of the Rione X (Campitelli) from the urban cadastre of Rome (1871). Rome, ASR — SIS, Presidenza generale del censo, Catasto urbano di Roma, Campitelli, Allegato, 2-II. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Archivio di Stato di Roma.

Fig. 3. Robert Smith's proposal for the opening of a gate in via dei Cerchi 46, Rome (1851). Rome, ASC, Amministrazione, Comune pontificio, Titolo preunitario, Titolo 62, busta 3, fascicolo 137. Courtesy of the Sovrintendenza Capitolina — Archivio Storico Capitolino.

We shall return to the photographic print showing the gate to this Villa Smith later, when it will activate one of the arguments of this article.

INTRODUCTION

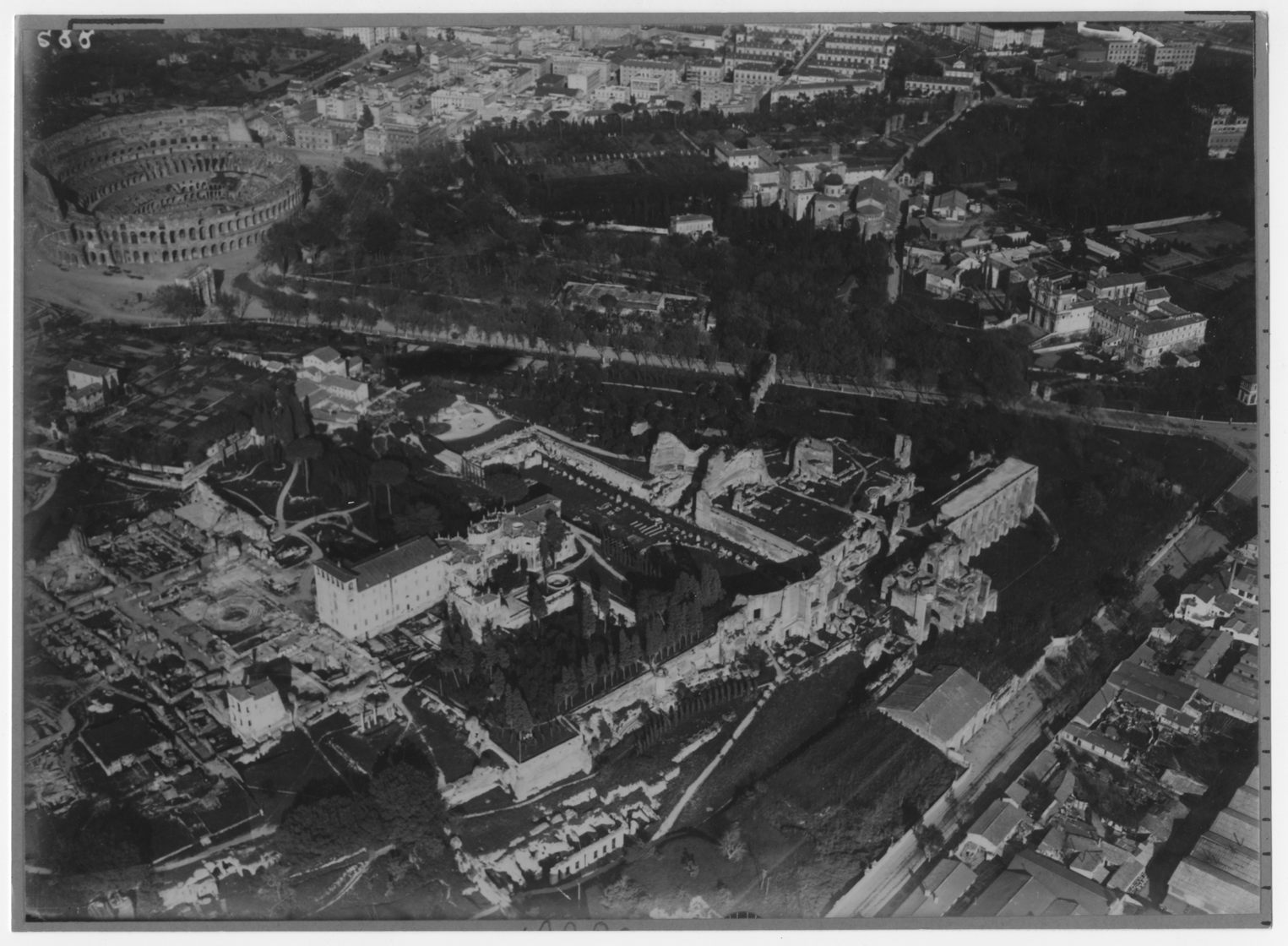

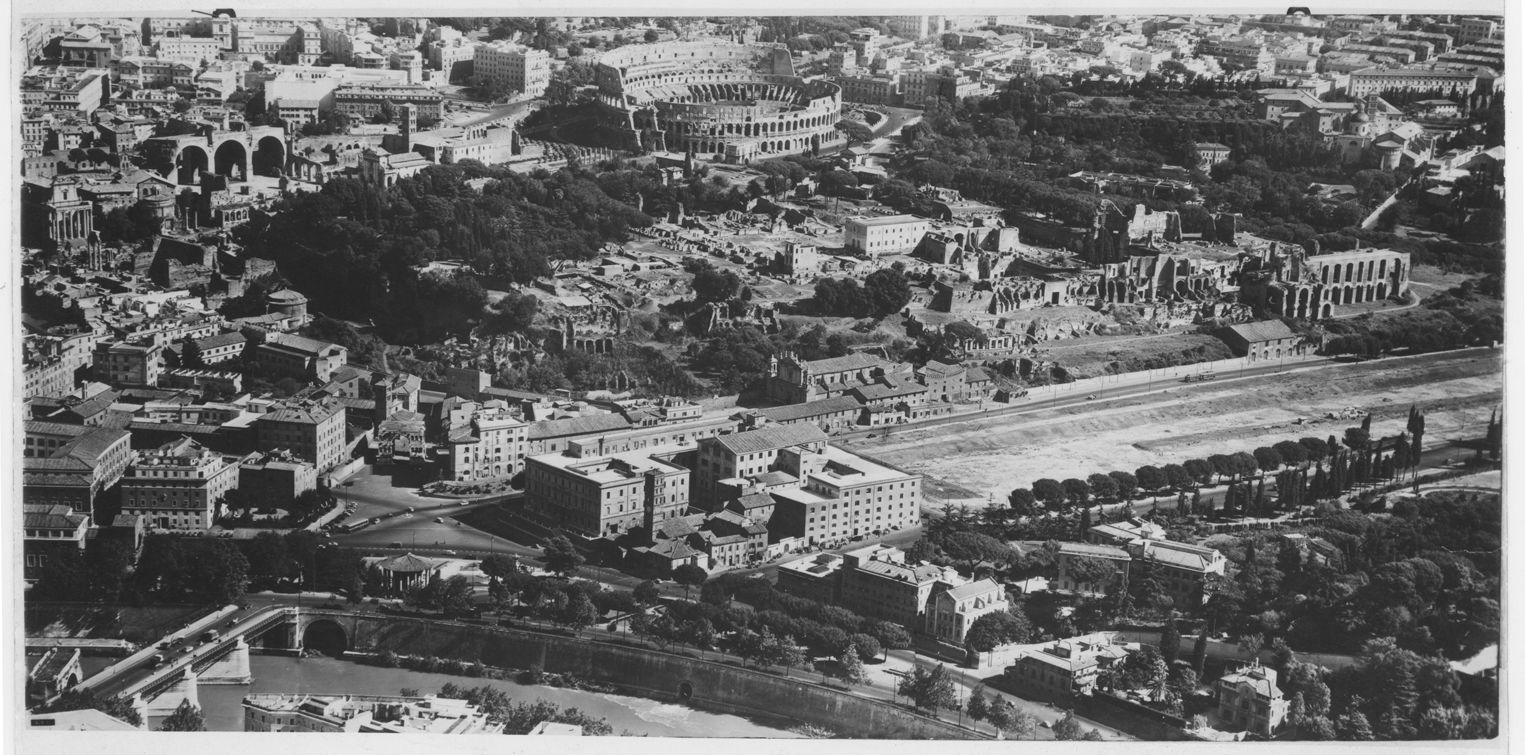

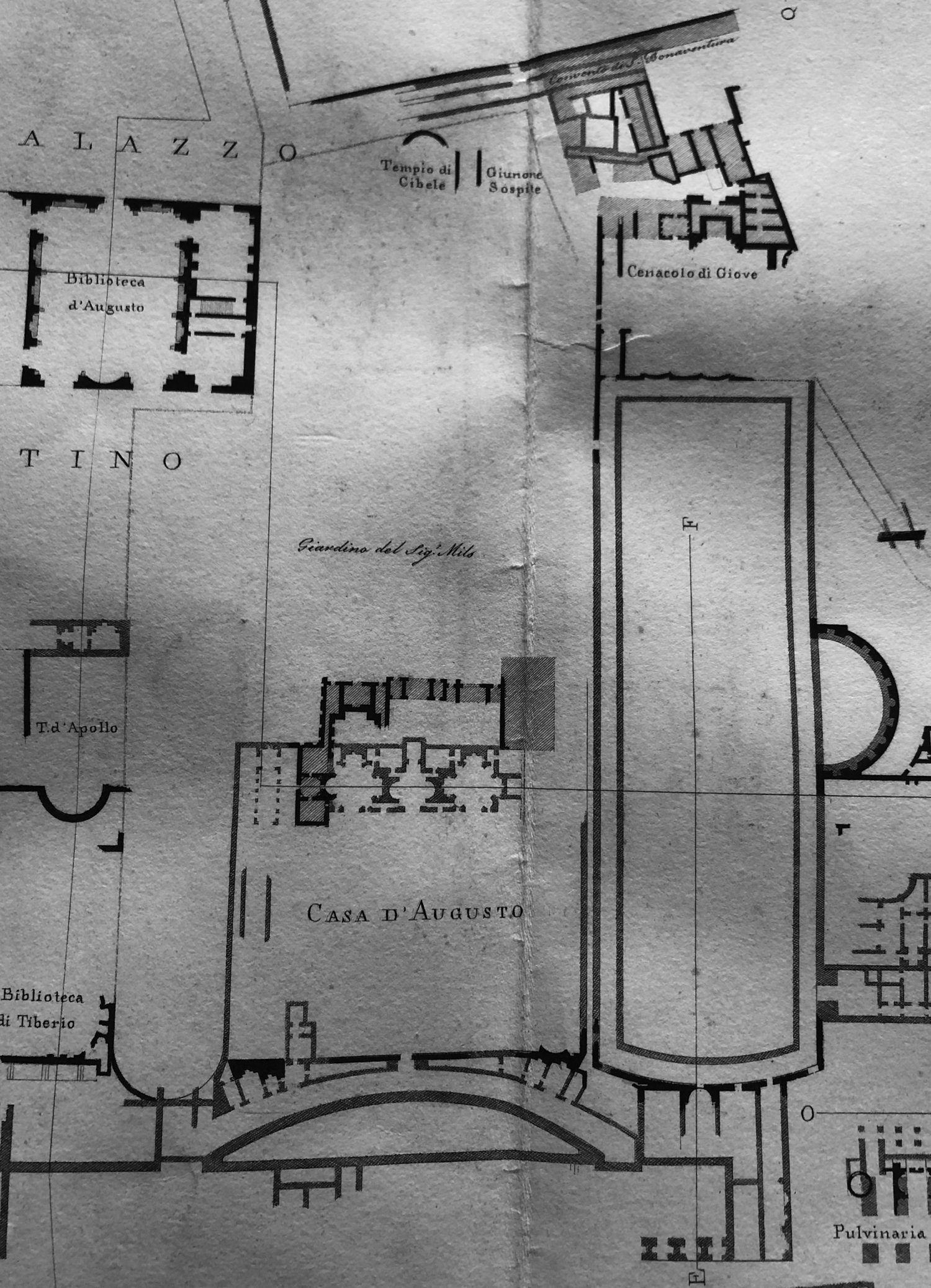

One of Britain's foremost travel writers of the twentieth century, H.V. Morton (1892–1979), achieved international fame in the 1920s by covering the sensational opening of Tutankhamun's tomb. In the appendix to a travel book first published in 1957, he reconstructs a biography of a Charles Andrew Mills (1770–1846) (Morton, Reference Morton1958: 417–20).Footnote 3 Morton (Reference Morton1958: 417) presents him as a member of the Legislative Council on the island of St Kitts, a descendant, on his father's side, of a London goldsmith who had made his fortune in the West Indies and, through his mother, of a Scottish soldier of fortune who had been appointed governor of the Leeward Islands. Following the loss of his role as Collector of Customs in Guadeloupe (1809–17), the journalist adds, Mills acquired a property that was soon turned into ‘shades of Strawberry Hill and Fonthill Abbey’, as the owner ‘built himself a Gothic villa’ (Morton, Reference Morton1958: 156, 417, 419). This article reveals that this Gothic Revival mansion, known as ‘Villa Mills’, should be renamed ‘Villa Smith’, as primary evidence suggests that Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Smith (1787–1873), a former official of the East India Company, acquired the property from Mills (in 1846) and pursued the medievalist makeover (Figs 4 and 5). The intervention might not seem surprising in the age of Victorian medievalism and Gothic (Parker and Wagner, Reference Parker and Wagner2020). Yet Villa Smith was not located in Britain, nor in any of its formal or informal colonies, but, surprisingly enough, in Rome, where the Gothic Revival might appear as a striking, and sporadic, anomaly. What is even more surprising is that it was erected atop the Palatine Hill, where it incorporated Villa Mills, formerly Villa Magnani — and, prior to that, Villa Spada, Mattei (di Giove) and Stati — above the Domus Augustana (Fig. 6).Footnote 4 While housing the Loggia Stati–Mattei (Baroni and Parapatti, Reference Baroni and Parapatti1997), with sixteenth-century painterly works that have been attributed to Raffaello, Raffaellino del Colle, Baldassarre Peruzzi or Giulio Romano (Cortilli, Reference Cortilli, Assmann, L'Occaso, Loi, Moschini, Russo and Zurla2021: 315), the edifice rested on the walls of the palace erected by Domitian towards the end of the first century AD. Villa Smith was turned into the monastery of the Sisters of Visitation in the second half of the nineteenth century and then demolished (sparing the Loggia Stati–Mattei) in the first half of the twentieth century, to reveal the Roman structures (Figs 7 and 8). Starting with preliminary investigations in 1907, which led to Alfonso Bartoli's (1874–1957) claimed discovery of the Oratory and Monastery of Saint Caesarius beneath ‘Villa Mills’, but mostly during the ventennio — after the death of Giacomo Boni (1859–1925) and the appointment of the archaeologist from Foligno as the director of excavations in the Forum and on the Palatine (1925–45) — the neo-Gothic mansion was erased from the Palatine Hill (Bartoli, Reference Bartoli1907, Reference Bartoli1929, Reference Bartoli1938; Spera, Reference Spera2017).

Fig. 4. The northeast front of Villa Smith, Rome. Giovanni Gargiolli (1838–1913), n.d., photographic print. Rome, ASGFN, E001934. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione.

Fig. 5. The southwest front of Villa Smith, Rome. Esther Boise Van Deman (1862–1937), n.d., photographic print, 18 × 24 cm. Rome, AAR, Photo Archive, Van Deman Collection, VanDeman. 715. Courtesy of the American Academy in Rome.

Fig. 6. View of the Palatine Hill from northeast, with Villa Smith in the background, between the Convent of Saint Bonaventura and the Farnese Aviaries, Rome. Félix Benoist (1818–1896), Palais des Césars sur le Palatin, vue de l'entrée principale, prise de la Basilique de Constantin, 1870, lithograph, 25 × 36 (on 35 × 50) cm, in Rome dans sa grandeur. Courtesy of the author.

Fig. 7. Undated aerial view of the Palatine Hill from west prior to the demolition of Villa Smith, Rome. To the left of the villa is the extension commissioned by the Sisters of Visitation. Rome, AN, Aeronautica Militare 0_Foglio 150_Strisciata PROSP_Fotogramma 688_Negativo 274917_0. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione.

Fig. 8. Undated aerial view of the Palatine from west after the demolition of Villa Smith. To the left of the Domus Augustana is the Palatine Antiquarium. Rome, AN, Aeronautica Militare 0_Foglio 150_Srisciata PROSP_Fotogramma 0_Negativo 109679_0. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione.

Around the time of these preliminary investigations, A.J. Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1906) published an article on ‘La Villa Mills sul Palatino’, followed by Bartoli's (Reference Bartoli1908) ‘La Villa Mills al Palatino’. The former does not add much to the statement that Villa [Smith] recalls a maison hantée. The latter is a call to action to demolish it, rather than a critical study. To this day, the topic is haunted by vague, imprecise and even wrong information. One can point to the attribution of the medievalist renovation to Mills, a misconception that this essay will link to both a superficial reading of the edifice by the pioneering archaeologist of ancient topography Rodolfo Lanciani (1845–1929) and the Roman legacy of the character of Mills. The villa, in contrast to the previous heirlooms of the Palatine (the imperial ones, especially), has not garnered an equivalent degree of scholarly interest.Footnote 5 This is not surprising. After all, the edifice is for Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1906: 158) a mere ‘watchful guardian of the grandiose ruins of the Palatine Hill’ (‘vigile custode delle rovine grandiose del Palatino’). Despite the explicit caveat to conduct the excavations ‘so that the monuments of a given time are not sacrificed in favour of those of a different epoch’ (‘in modo che non si sacrifichino monumenti di un dato tempo a preteso vantaggio di quelli di altra epoca’), Bartoli (Reference Bartoli1908: 102) — while concerned to ‘scrupulously save what is left in there not only from the Empire but also from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance’ (‘scrupolosamente salvare quanto in essa è rimasto e del tempo imperiale non solo ma e del medioevo e del Rinascimento’) — ignored modernity and sacrificed Villa Smith in favour of the Domus Augustana (Fig. 9).Footnote 6 Aside from brief mentions of ‘eccentric’ architecture in Rome's built environment — such as C.L.V. Meeks's (Reference Meeks1966: 212) presentation of the villa as ‘an improbable Gothic mansion, an example of uninhibited Romanticism’, which ‘stood on the Palatine, of all places’ — very little has been written about the edifice. One could name, in particular, a contribution by L. Jannattoni (Reference Jannattoni1987) in the Strenna dei Romanisti; a volume on the history of the area of Villa Mills e la Domus Augustana by M.E. Garcia Barraco (Reference Garcia Barraco2014); and an article by G. Olthof (Reference Olthof2019). Despite these efforts, knowledge of this architecture is often contradictory and tends to derive from hearsay and hypothesis rather than primary information. Questions on the construction phase, patron and author of the neo-Gothic intervention (Villa Smith), and the condition of the villa prior to this intervention (Villa Mills), remain to be answered. In addition to these struggles, the building suffered an overbearing damnatio memoriae. For instance, after the demolition, the fascist architect Marcello Piacentini (Reference Piacentini1952: 8) — echoing an expression previously adopted by Bartoli (Reference Bartoli1908: 102) (‘indecorous pseudo-medieval mask’) — addressed it as ‘that vile pseudo-Gothic villa, now, if God wills, demolished’ (‘indecorosa maschera pseudo-medioevale’; ‘quella ignobile villa pseudo-gotica, ora, se Dio vuole, demolita’).

Fig. 9. Alfonso Bartoli stands in front of a pier of the northeast porch of Villa Smith, in demolition to recover the Domus Augustana, Rome. Soprintentenza alle Antichità Palatino e Foro Romano, Villa Mills, fronte nord, particolare, June 1927, photographic print on card. Rome, ASPArCo, Archivio Fotografico, Villa Mills, VM-FN 002-asf022617. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Parco Archeologico del Colosseo.

The state of knowledge of the ‘foreign’ ownership of the Domus Augustana during the modern era is not more encouraging. Very little information — at times very confusing — has been recorded about (Charles Andrew) Mills. This includes, as this article reveals, an erroneous identification with a different (Charles) Mills. It is nonetheless relatively well known that our Mills lived on the Palatine Hill, as it is that he was not the only Briton that once owned the property. Morton (Reference Morton1958: 419–20) did not fail to highlight that, in 1818, the estate had been purchased by the pioneering scholar of the classical world Sir William Gell (1777–1836) — even though claiming that ‘he had acquired this property jointly with’ Mills — nor did he fail to briefly mention that it ‘then came into the possession of … Smith’. Even if sporadically, the literature on the Eternal City had already mentioned the association between the Palace of the Caesars and Smith — long before the publication of A Traveller in Rome, and starting from the year in which the British official had purchased the estate.Footnote 7 The scholarship on Smith, instead, including a pioneering article by M. Archer (Reference Archer1972), for a long time ignored this purchase altogether. While exploring his experience in England and in the East, respectively, D. James (Reference James, Finn and Smith2018: 286–7) and S. Shorto (Reference Shorto2018: 102–5) have more recently addressed Smith's ownership of the Roman villa. The latter even indicates, albeit without providing the exact source for this information, that Smith was not the last possessor of the estate before the acquisition by the Sisters of Visitation (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 105). Yet no significant attempts have been made to focus on his (nor on the broader foreign) ownership of, and presence above, the Domus Augustana.

Via the presentation, and thorough scrutiny, of a broad range of visual and textual sources, including extensive notarial paper trails, this article sets out to fill these gaps and offer a close study of the villa and of British presence atop Rome's imperial hill. Yet its scope goes beyond architectural and biographical discourses and matters of ownership, to reflect upon the relationships between architecture and political and cultural intent, between Italy and Britain, and between modernity and antiquity. A rich literature has considered the connections of Italy and Britain in the modern era, including investigations of the impact of Rome and its architecture on Britain's architects and architectural culture (Salmon, Reference Salmon1995, Reference Salmon2000). The spatial implications of British presence in the Eternal City, and the modes through which this presence was asserted in the urban fabric, remain much less explored. In this capacity, a recent study has suggested that the English church of All Saints’ (1880–7) — alongside George Edmund Street's other neo-medieval design for the Anglicans in Rome, the American Episcopal church of Saint Paul's Within-the-Walls (1872–6) — emerged as an architectural manifestation of the negotiations and cultural politics of post-conquest Rome (Bremner, Reference Bremner2020). Through the case of Villa Mills/Smith, this article turns attention to secular architecture, to the reuse of pre-existing palimpsests and to pre-unification Rome. By covering the period from the 1810s to the 1850s, it provides an insight into Anglo-Italian relations vis-à-vis the return of Pius VII to Rome (1814), the parenthesis of the Roman Republic (1849), the challenges of revolution and the Italian Risorgimento, and Britain's growing imperial anxieties.Footnote 8

This study does not focus on an architectural reading of Villa Smith, nor does it discuss the life of the edifice and the estate under the Sisters of Visitation first and the Italian state thereafter, or the cultural and political dynamics at play in its demolition and damnatio memoriae. These topics will be the subject of a broader project, which is only anticipated here. While disentangling a history of the foreign ownership of the Domus Augustana in the nineteenth century, the first two sections of the article reflect on British presence in Rome, with the first one dedicated to the period from the Restoration to the sale of the property to Smith, and the second one ending with the sale to the nuns. The third section investigates the person behind the neo-Gothic reworking. The fourth section argues that, prior to Smith's interventions, Villa Mills was not a Gothic Revival edifice. It offers a critical reconsideration of both the villa and the character of Mills.

BRITAIN AND THE PALATINE

On the cusp of Romanticism, starting with the sunset of Napoleonic Italy which led to the restoration of the Papal States by the Congress of Vienna, a glittering array of British personalities came to — and was spellbound by — the Eternal City.Footnote 9 These personalities included poets, painters and architects — such as Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats, William Turner and Charles Robert Cockerell.Footnote 10 They also include our Charles Andrew Mills, Esq. — from a long-established family in St Kitts, the son of Peter Matthew Mills and Catherine Hamilton (Morton, Reference Morton1958: 417) — and Sir William Gell (Fig. 10), the author of, among others, The Topography of Troy, and Its Vicinity; Illustrated and Explained by Drawings and Descriptions (published in Reference Gell1804) and Pompeiana: The Topography, Edifices, and Ornaments of Pompeii (first published in Reference Gell and Gandy1817–Reference Gell and Gandy19 with J.P. Gandy), which is the first English-language account dedicated solely to the description of the site of Pompeii.Footnote 11

Fig. 10. Portrait of William Gell. Thomas Uwins (1782–1857) (engraved by Fenner Sears & Co.), Sir William Gell, M.A. F.R.S. & F.S.A., in Gell (Reference Gell1837). Rome, BH, E-POM 120-4370/1. Courtesy of the Bibliotheca Hertziana — Max Planck Institute for Art History.

‘Classic Gell’ — as Byron referred to him in 1810 (Sweet, Reference Sweet2015: 254) — arrived in Italy in 1814 as part of Caroline of Brunswick's (1768–1821) loyal court after the princess (afterwards queen) had been estranged from her husband, who would ascend to the throne in 1820 as George IV (Thompson, Reference Thompson2019: 31–46). Gell's resignation from the role of chamberlain and private secretary to Caroline (on grounds of poor health) and the grant of an annual pension of £200 (February 1815) that, at least temporarily, contributed to easing his financial struggles enabled him to dedicate himself to scholarly activity in Italy (Thompson, Reference Thompson2019: 46–9). The decision to move to Rome, where he was soon elected to the Roman Academy of Archaeology, might be explained by his particular research interests, resulting in the publication, with Antonio Nibby (Reference Gell and Nibby1820), of Le mura di Roma and, especially, The Topography of Rome and Its Vicinity (Reference Gell1834) (Sweet, Reference Sweet2015: 247). The estate he acquired on the Palatine Hill presented ‘an unrivalled view of Rome and the Campagna’, noted Marguerite Gardiner, the Countess of Blessington (Reference Blessington1839: 470). The area was of extraordinary archaeological interest — and had been since at least the sixteenth century (Iacopi, Reference Iacopi1997). The purchase took place in 1818, when British presence was reinforced in the city by the establishment of the services of the Church of England and the revival of the Venerable English College.Footnote 12 On 9 April 1818, a notarial deed was drawn up in via Frattina 122 — Gell's address in Rome at that time — between Count Angiolo Colocci di Jesi, son of Francesco Patrizio, and the English scholar, who was still referred to as ‘Chamberlain of H.R.H. the Princess of Wales’ (‘Ciamberlano di S.A.R. la Principessa di Galles’).Footnote 13 The former sold to the latter ‘The villa once called Magnani surrounded by boundary walls … nearby the Convent of S. Bonaventura, bordering the Orti Farnesiani [to the east], the [Palatine Stadium leading towards the] English Garden [to the west], and the public road leading to said Convent [to the north], with the Casino and every object’ (‘La Villa una volta denominata Magnani circondata di mura … presso il Convento di S. Bonaventura, confinante da un lato gli Orti Farnesiani, da altro l'Orto Inglese, da altro la strada pubblica che porta al detto Convento, con Casino e tutti gli oggetti’) for ‘2,650 silver Roman plates’ (‘piastre romane d'argento’). Notary Luigi Gallesani reports that the property had been acquired by Count Francesco Patrizio Colocci di Jesi on 3 January 1781 from the French abbot Paul (‘Paolo’) Rancurel — famous for pursuing a campaign of excavations in the area between 1774 and 1777 (Pafumi, Reference Pafumi2007) — and then sold to Paolo Montagnani, who gave it back to the Colocci di Jesi due to insolvency.Footnote 14 The document does not include a detailed description of the estate, nor is it accompanied by a drawing. Yet a map of the Palatine Hill, dated 1820 and conserved in the Archivio di Stato, offers a rare depiction of Villa Gell, and its gardens and environs (Fig. 11). Indeed, Gell owned the property for less than three years. On 9 February 1821, ‘Sir William Gell … Chamberlain of H.M. the Queen of England’ sold the estate to Mills for 2,850 golden and silver Roman coins.Footnote 15 This sale must have helped to ease his financial woes — which were worsened in the same year by the death of his greatest patron, Queen Caroline (7 August), and the beginning of the issues with the assignation of the pension she had granted him.

Fig. 11. Villa Gell and its surroundings, Rome. Detail of Colle Palatino, 1820, pencil, ink and watercolour on paper, 54 × 69.5 cm. Rome, ASR — SIS, Collezioni disegni e mappe, 89-640/1. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Archivio di Stato di Roma.

The correspondence from Caroline to Gell attests that Mills was close to both of them (Thompson, Reference Thompson2019: 205, 230–1, 233, 240, 243, 246, 252). In 1820, Gell and Mills were in London to testify at her infamous trial.Footnote 16 Richard Grenville (Reference Grenville1862: 17), the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, noted in his diary that Mills was ‘famous for having come over at the head of the Queen's witnesses during her trial, and as having perjured himself more than most of them’. The proceedings (The Important and Eventful Trial, 1820: 598) inform us that Mills resided in Rome in 1820 — before his acquisition of the estate on the Palatine. Mills reported spending only ‘about 12 days’ in Rome during summer 1817 (The Important and Eventful Trial, 1820: 598). This enables us to suggest that, dismissed from his post in Guadeloupe and back to England, he did not settle in Rome before the autumn of the same year, probably not before 6 October 1817 when, Morton (Reference Morton1958: 417–18) has noted, Mills wrote to Charles Arbuthnot (one of the joint secretaries of the Treasury to whom he appealed against the dismissal), expressing the wish to go to the continent for a short time, as his health demanded a change of scenery. Such change of scenery proved long-term, as his name was to be remembered for the estate he owned for 25 years in Rome. Where he resided in the Eternal City prior to becoming the owner of the property on the Palatine, and the extent of the relationship with Gell remain matters of speculation — just like the extent of the relationship between Gell and Keppel Craven (1779–1851), also a chamberlain of Princess Caroline and executor of the scholar after his death.Footnote 17 It cannot be ruled out that Mills lived in the villa prior to the acquisition from Gell, something which could explain Morton's belief that the two had jointly acquired the estate. It can be convincingly argued that neither the sale of the villa nor the decision to move to Naples, where he died in 1836, put an end to Gell's relationship with Rome, Mills and the villa. After all, the Countess of Blessington (Reference Blessington1839: 565) noted that, on her farewell to the city in May 1828, she had dined on the Palatine, ‘where our kind friend Mr. Mills has assembled those of our Roman friends most dear to us, with our good Gell, and Mr. and Mrs. Dodwell’.

Indeed, the two Englishmen were well known among visitors and expatriates in Italy from the British Isles. The Irish painter and archaeologist Edward Dodwell (1767–1832) made them his executors. After the death of Dodwell, the young Roman architect Virginio Vespignani (1808–1882), his collaborator, reported to Gell and Mills the updates on the drawings for Views and Description of Cyclopian, or, Pelasgic Remains in Greece and Italy (Dodwell, Reference Dodwell1834).Footnote 18 In 1832, a fatigued Sir Walter Scott was escorted by Gell on his Italian adventure (Riccio, Reference Riccio2013: 45–58; Thompson, Reference Thompson2019: 133–6). His profile was captured in a small sketch by Michelangelo Caetani (1804–1882) during a visit to Frascati (Gorgone and Cannelli, Reference Gorgone and Cannelli1999: 92–4). Filippo Caetani (1805–1864), younger brother of the author of this, one of the latest depictions of the Scottish poet, created the only known likeness of our Mills (Fig. 12).Footnote 19 The watercolour caricature, showing a slim figure with large forehead, arched brows, hooked nose, puffy cheeks, and a hat in his left hand, offers us a glimpse of the character that made a name for himself in Rome, not just among fellow Britons or local high society. More than the tragic discovery of the body of Rosa Bathurst in the Tiber (Thistlethwayte, 1853: 286; Caetani, Reference Caetani and Fiorani2005: 103), Mills's name was inextricably linked to his Roman villa.

Fig. 12. Caricature of Charles Andrew Mills. Filippo Caetani, C. Mills, in the ‘Roma 1833’ album, c. 1833, pencil and watercolour on paper, 12.6 × 8.8 cm. Rome, FCC, Caricature di Filippo Caetani, Album A. Courtesy of the Fondazione Camillo Caetani.

In the Rome of the Restoration, Mills turned the Palatine — the same place that Byron (Reference Byron1818: 56) had described as ‘one mass of ruins, particularly on the side towards the Circus Maximus’ — into a sophisticated window onto the past, that welcomed visitors of different nationalities and backgrounds. In a well-known passage, the Countess of Blessington (Reference Blessington1839: 550–3) reported on an encounter with the Prince and Princess de Montfort and Letitia Bonaparte in May 1828. Napoleon's mother was not the only Bonaparte to visit the estate, as two watercolours at the Museo Napoleonico portray Charlotte Bonaparte's visit to — what, in the 1820s, was becoming known as — ‘Villa Mills’, and her fascination with its archaeological curiosities and environs.Footnote 20 Yet, on the Palatine, Mills did not entertain and astound just the wealthy with the extraordinary location of his residence. In Rome: A Tour of Many Days, resulting from his ‘545 days’ in the city between 1838 and 1842, G. Head (Reference Head1849: 69) noted that ‘A general admittance to the grounds is granted to the public every Friday’ — and, following ‘a special order from the proprietor’, visitors could even ‘enter the casino’. Similarly, in an account of G. Melchiorri (Reference Melchiorri1840: 611), Mills ‘kindly welcomes anyone who would like to visit’ the villa (‘cortesemente permette a tutti di visitarla’). While diametrically opposite to Rancurel's use of the estate, the opening of the site to the general public makes Mills a true pioneer of archaeological museumization on the Palatine. Indeed, G. Head (Reference Head1849: 69) remarked that ‘Mr. Mills is generally distinguished among the Roman Ciceroni’. Thus, it should not surprise that, in a beautiful watercolour from 1886 — 40 years after the death of Mills — which depicts the Palatine from the southwest, the French architect Henry-Adolphe-Auguste Deglane (1855–1931) labelled the Gothic Revival mansion emerging from the cypresses as ‘Villa Mills’ (Fig. 13). The legacy of Villa Mills did not end with the death of the British gentleman, as his name was, and still is, associated with the estate that he once owned on the Palatine — an association which greatly added to the myth that Mills was behind the Gothic makeover.

Fig. 13. Henri-Adolphe-Auguste Deglane, Mont Palatin, Palais des Césars, façade du côté du grand cirque, état actuel MDCCCLXXXV, 1886, ink and watercolour on paper. Paris, ENSBA, Env 76-03. Courtesy of the Beaux-Arts de Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais.

An English duplicate of a French will made in Paris on 27 June 1842 expresses Mills's intention to make his brother's daughter, Catherine Amelia (who by marriage was Baroness Gallus de Glaubitz), his universal heir.Footnote 21 The document, in which Mills is referred to as ‘usually residing at Rome’ and ‘in possession of a villa … in the said city of Rome’, does not reveal much about the estate on the Palatine, as it pertains to all of Mills's possessions, ‘exempt my property and effects in Italy’. These were the subject of a Roman testament — which Morton (Reference Morton1958: 420), who first discussed the French one, could not find. I have located this deed, drawn up by Mario Damiani (Protonotaro del Senatore) on 17 March 1834, in the documentation on the opening of the will of Mills conserved in the Archivio Storico Capitolino.Footnote 22 This documentation includes an additional testamentary note by the same notary and dated 12 April 1837. In this testament, revoking a previous one made in Rome in May 1827 and disposing of his Italian possessions (‘de’ miei beni d'Italia’), likewise in the French will, Mills appointed as universal heir his ‘most beloved niece Catherine Amelia born Mills and consort of Baron Gallus de Claubitz [sic] of Strasbourg’ (‘dilettissima nipote Caterina Amelia nata Mills, e consorte del Sig Barone Gallus de Claubitz [sic] di Strasburgo’). Yet his ‘most beloved niece’ was not meant to inherit the villa. The will gives precise instructions to the testamentary executors (‘Cavalier Luigi Chiaveri, e Dottor Antonio Pagnoncelli’) to sell, after Mills's death, anything that is not mentioned in the document — including, within six months, the villa itself — and to give the related revenue to her, sparing the sum to pay any debt and what he aimed to bequeath to staff and acquaintances. There was no need for this, as the villa was sold before Mills's death. According to the additional testamentary note, Mills was still living on the Palatine on 12 April 1837. G. Head (Reference Head1849: 69), who visited the estate sometime between 1838 and 1842, reported it being ‘uninhabited by the proprietor, and left, together with the gardens, under charge of a custode’. When Mills moved out of the villa is uncertain. By reporting that Mills died on the night of 3 October 1846 in Mr Rinaldini's inn in piazza di Spagna 25, where he resided, the document for the opening of the will attests that Mills had left the Palatine sometime before his death, to live in the (area that once was the) heart of the so-called ‘English Quarter’.Footnote 23 Indeed, in Roma veduta in otto giorni, F.S. Bonfigli (Reference Bonfigli1854: 6) noted that, in piazza di Spagna 25, Mr Rinaldnini ‘has several furnished apartments, which he rents by month or for the winter’ (‘ha parecchi appartamenti mobiliati, che affitta per mese o per tutta la stagione d'inverno’). The location of number 25 in the urban cadastre (1871) of the Rione Campomarzo — a number which can still be spotted on the façade in piazza di Spagna — suggests that Mills died in the edifice below the stairs of Trinità dei Monti, opposite the one where Keats had died in 1821 (the Keats–Shelley House).Footnote 24 The owner of civic numbers 22–5 (corresponding to cadastral number 1178) was Giuseppe Canali first (in the proceedings of the cadastral census that was ordered in 1818) and then Laura Canali (in the so-called ‘Aggiornamento’ of 1871).Footnote 25 Mills was already living there on 5 April 1846, when Damiani drew up a notarial deed for the appointment of Pagnoncelli as Mills's legal representative for the sale of the estate.Footnote 26 The day after, acting for Mills, Pagnoncelli sold, for 8,000 scudi romani, ‘The Villa called Mills’ (‘La Villa denominata Mills’) to ‘Sig.r Colonnello Roberto Smith’.Footnote 27

A TALE OF DEATH, INFIDELITY AND THE NEO-GOTHIC

The villa passed from an Englishman who had served the Crown overseas to another. Unlike Mills, there is a known portrait of Smith, which R. Head (28 May Reference Head1981: 1524) included in his account of the life of the ‘artist, architect, and engineer’ (Fig. 14). James (1740–1839) and Mary (1760–1838) Smith, his parents, lived in Bengal in the early 1780s, where his two elder brothers were born (R. Head, 21 May Reference Head1981: 1432; Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 84–5). The son of ‘Giacomo’, notarial documentation reports that Robert Smith came from London (‘nativo di Londra’) — where the family had moved upon return from the East.Footnote 28 Yet Robert Smith was born on 13 September 1787 in France and baptized in Nancy (R. Head, 21 May Reference Head1981: 1432; Biographical Dictionary, 2002: 637; Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 84). Raised in London, Robert spent much of his childhood in Bideford, where the Smith family had their home (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 85). This information finds confirmation in archival documentation in Rome, according to which Smith was from ‘Devonshire in Inghilterra’.Footnote 29 The family must have had some ties with the East India Company, as four brothers out of four (sparing the couple's two daughters) later joined the company as ensigns (and were promoted to at least the position of lieutenant-colonel) — all but Robert died abroad (R. Head, 21 May Reference Head1981: 1432; James, Reference James, Finn and Smith2018: 278). In 1803, prior to arriving in India and joining the Bengal Infantry and, soon after, the Bengal Engineers (1805), Smith became a cadet at the East India Company's college at Great Marlow, an experience which informed his career as engineer-architect, artist and soldier (R. Head, 21 May Reference Head1981: 1432). A talented painter from childhood, at Marlow he was instructed in mathematics, fortifications and draughtsmanship (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 86). Among other appointments, he was field engineer in the Nepal War (1815–16), superintending officer in Penang and — after a leave on furlough to England starting in 1819, the publication, in 1821, of Views of Prince of Wales Island, and his return to India in 1822 — garrison engineer of Delhi (R. Head, 21 May Reference Head1981). An acclaimed and highly skilled draughtsman and surveyor, he provided, via sketches and landscape paintings (including topographical panoramas, and ranging from watercolours to oil on canvas), a glimpse of the British gaze — and of British presence — in the East (Archer, Reference Archer1972; Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 86–9). As an engineer-architect, his name in India is associated with the construction of several buildings, military and non-military, in Delhi and beyond, such as Ludlow Castle and the Flagstaff Tower, but also Saint James's Church and his very house, used today as offices by the Northern Railways Construction Department (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 81–3, 91–9). It is also associated with the campaigns of ‘preservation’ and recrafting of local historical sites that added to a colonial narrative of rescue, ranging from the work on the Kashmir Gate and the reinforcement of Delhi's defensive walls, to the interventions on Shah Jahan's Jama Masjid and on the late twelfth-century Qutb Minar at Mehrauli (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 89–92). Unlike Mills, Smith returned to Britain with full honours. Prior to retirement (which took place in July 1832, at age 44), he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in June 1830 and created a Companion of the Order of Bath in September 1831 (James, Reference James, Finn and Smith2018: 285). In November 1854, he was awarded the title of honorary colonel (Phillimore, Reference Phillimore1950: 442; James, Reference James, Finn and Smith2018: 285). R. Head (21 May Reference Head1981: 1434) has highlighted that ‘his artistic achievement lapse[d] into obscurity’ — not least because ‘he seems deliberately to have chosen not to concern himself with the eventual fate of his paintings’, which were dispersed after his death. Smith's activity in India is nonetheless well documented, including sketchbooks, watercolours, and oil on canvas in the British Library's collections.Footnote 30 More ‘obscure’ remain the years between his retirement and the acquisition, in the 1850s, of estates in Paignton (Devon) and Nice — in particular, the years of his wedding with Julia Adelaide Vitton and the couple's stay in Italy (R. Head, 28 May Reference Head1981: 1524).

Fig. 14. Head and shoulders portrait of Captain Robert Smith (1787–1853), Bengal Engineers. Raja Jivan Ram, c. 1830, oil on canvas, 29 × 24.5 cm. London, BL, Foster 870. Courtesy of the British Library Board.

It is not difficult to imagine a retired Smith wanting to spend time in Italy, where the polymath could cultivate his varied interests — ranging from mathematics to landscape painting and architecture — and follow in the footsteps of many compatriots before him. While R. Head (28 May Reference Head1981: 1524) has claimed that Smith and Julia married in Florence, according to Shorto (Reference Shorto2018: 101), ‘early in 1840’ the couple married ‘in Savoy’, but no evidence is presented in either case. G.B. Contarini's work on the tombstones erected in Venice in the first half of the nineteenth century (Reference Contarini1844: 269), reporting an epigraph that ‘ROBERTO SMITH COLONNELLO DI S.M. BRITANNICA’ and ‘GIULIETTA NOB. VITTON’ dedicated, on 5 May 1843, to their infant children ‘GIOVANNI — EDOARDO — MARIA’, enables us to situate the Smiths in Italy in the early 1840s. Of the four children born to them in Venice from 1840, only the youngest, who was born on 9 March 1843, survived infancy (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 101). His name was Robert Claude, whom, after the colonel's death, The Law Times Reports (In the Goods of Co. R. Smith, 28 February 1874) referred to as Robert's ‘only lawful and natural son’. The British official seems to have travelled around in Italy, in his own version of the Grand Tour. ‘Smith Roberto, Inglese, Colonnello ed ingegnere degli stabilimenti Inglesi delle Indie (Matematica)’ figures in the Diario (1845: 142) of the seventh Congress of Italian Scientists, held in Naples between 20 September and 5 October 1845.Footnote 31 At the time of the deed with Mills, he was accommodated in Rome, in via della Fontanella di Borghese 35.Footnote 32 The acquisition of an estate in the Eternal City, facilitated by British presence in the city and by the sale from a fellow Englishman, suggests that the Smiths had serious intentions for their stay in Italy.

Smith put some effort into the improvement of the estate. On 19 August 1848 — following the appointment, on 20 June 1848, of lawyer Francesco Costa as his representative for the transaction — he acquired, for 800 scudi, water supply (‘un'oncia e mezza’) of Acqua Felice from Gaspare Conti.Footnote 33 On 20 July 1849, notary Giovanni Franchi ratified Smith's acquisition, for 750 scudi, of an orchard from Giuseppe Brogi.Footnote 34 This property, situated between the Circus Maximus and Smith's estate on the Palatine, granted direct access on to via dei Cerchi.Footnote 35 The transaction is illuminating on multiple accounts. Pagnoncelli — who had represented Mills before that date — acted in place of Smith for the purchase. This underpins the presence of a Roman intelligentsia which specifically negotiated with British expats. A private deed had been drawn up on 23 December 1848.Footnote 36 The delay in the fulfilment of the sale highlights the impact that the revolutionary climate of 1848–9 had on Italians and foreigners alike. Indeed, the sale drawn up on 20 July 1849 — which follows the end, on 4 July 1, of the Roman Republic — states that the ‘past political events … suspended postal communications, and interrupted the course of legal proceedings’.Footnote 37 Last but not least, by suggesting that the property would grant Smith the opportunity to ‘recover objects of artistic interest’, a report by engineer Cesare Brunelli, attached to the deed, draws attention to the permanence of antiquarian practices in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 38 In this sense, an undated letter from 1848 — in which Smith offered to buy a property that the government had acquired in via dei Cerchi to pursue archaeological excavations — highlights a rising interest of the state in the area.Footnote 39

More than a site where they could carry out excavations à la Rancurel and more than a holiday residence, the Palatine was where the Smiths set up home. Archival documentation records that Robert and Julia lived on the Palatine.Footnote 40 The acquisition provided the former with the opportunity to follow in the footsteps of fellow countrymen and draw inspiration from the Eternal City. Confirmation that he kept painting while in Rome, and that he was inspired by the surroundings of his Italian villa, may lie in a painting on canvas depicting the Fish Market / Portico d'Ottavia / Rome and signed ‘Robert Smith’ — sold by a French dealer some years ago.

Despite the lieutenant-colonel's commitment, the legacy of Mills in Rome was not eclipsed by that of Smith. The villa that incorporated the Domus Augustana is still known as ‘Villa Mills’ and the name of Mills was still used to refer to the villa during Smith's ownership.Footnote 41 Altogether, one would struggle to find references to ‘Villa Smith’, with some exceptions being the documentation relating to the opening of the new gate in via dei Cerchi, the introduction to I. Ruspoli's (Reference Ruspoli1846) album of lithographs on the Palatine Hill, and a plan showing the topography of the Orti Farnesiani, owned by the Crown of Bourbon-Two Sicilies — with the inscription ‘Villa Smitt [sic]’ on the left, demarcating the property of the lieutenant-colonel (see Fig. 3; Fig. 15).Footnote 42 The reason is that, while Mills lived on the Palatine for many years and built a solid reputation in Rome, the Smiths did not dwell for long in the city. The registration, on 22 March 1851, of a private deed in the Registro d'introito degli atti di firma privata of Rome reveals that, less than five years after the acquisition, Smith sold the ‘villa called Mills’ (‘villa detta Mills’) to ‘Conte Carlo Plowden, e Cavaglier Ugo Edoardo Cholmeley’.Footnote 43

Fig. 15. Topografia degli Orti Farnesiani nell'urbano di Roma al Campo Boario spettanti alla Real Corte di Napoli in appoggio dell'annesso rapporto, [between 1846 and 1851], ink and watercolour on paper, 38.5 × 48 cm. Rome, BiASA, Archivio Rodolfo Lanciani, Roma XI.7.II.29, 17691. Courtesy of the Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell'Arte.

After establishing the Plowden & French firm in Florence, Charles Plowden (Fig. 16) and his partner Anthony French signed a partnership agreement with Hugh Cholmeley (the brother of the wife of Charles's elder brother) to set up the branch in Rome in October 1843 — Plowden & Cholmeley or Plowden, Cholmeley & Co. and, after Cholmeley's death, Plowden & Co.Footnote 44 The ownership by the bankers — an ownership which constitutes the last chapter of the British phase of the property — anchors the history of the villa to a well-respected authority and a particularly precious resource for the English-speaking community in Italy. An obituary released in The Bankers’ Magazine (1884: 446) described Plowden, who ‘died at his residence, the Palazzo Doria’, as ‘the well-known banker’, who was ‘well known by the English colony at Rome, and by British travellers, for more than forty years’. The Roman Advertiser (11 November 1848: 235) — the first and short-lived (1846–9) journal in English published in Italy (Pantazzi, Reference Pantazzi1980) — reported his firm among the bankers at Rome and located at via del Corso 232.Footnote 45 Yet Plowden & Cholmeley carried out business that was not limited to banking. Blurbs in The Roman Advertiser (11 November 1848: 236) declared that the firm offered shipping services (including works of art) to ‘English Visitors to Rome and to the Continent generally’. While the services that had been offered to Smith remain obscure — perhaps support with his relocation and the shipping of his artworks — the British official owed some favours to the bankers. They managed to acquire the estate on the Palatine for the ‘very limited sum’ of 9,218 scudi.Footnote 46 It is likely that Plowden and Cholmeley saw this as an investment opportunity. It most certainly was a lucrative investment. On 31 December 1855, Cholmeley, representing the firm, and Giovanna Carlotta Rossi, 25th Mother Superior of the Monastery of Visitation, signed a long-winded deed through which the estate passed to the nuns for the considerable sum of 30,000 scudi.Footnote 47

Fig. 16. Portrait of Charles Plowden. Mayer & Pierson, 1860s, albumen carte-de-visite, 8.8 × 5.6 cm. London, NPG, Photographs Collection, NPG Ax46372. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

The sale to a Catholic institution was not surprising. Catholics formed the core clientele of Plowden, Cholmeley & Co., which forged profitable relationships with the Catholic Church.Footnote 48 An obituary released in The Tablet (23 April 1870: 533) to record the death of Cholmeley noted that the loss of ‘the well-known banker … will be much felt by the English Catholics now or formerly resident in Rome’. Smith's ownership of the estate, which followed Pius IX's accession to the Holy See (16 June 1846), spanned one of the most curious moments in Anglo-Italian relations, when, as S. Matsumoto-Best, (Reference Matsumoto-Best2003) has discussed, significant diplomatic attempts were being made to bring together two such traditionally hostile powers as Britain and the Catholic Church. The sale to the Monastery of Visitation sheds new light on the survival of a close relationship between the two after the failure of this policy, and discloses the mediating role that Plowden, Cholmeley & Co. had in the transition from a British phase to a ‘papal’ phase of the property on the Palatine.

The ties of the bank spanned well beyond religious entities, as the firm ‘Plowden’ had among its clients the British Academy of Arts in Rome, the enterprise formalized by a group of British artists in 1823 and closed in 1936 (Wells, Reference Wells1978: 107). This information opens a fascinating line of enquiry into the relations between the bank, the Academy and Smith — who had based his career upon the arts. His arrival in Rome might have been influenced by the presence of the British institute and the intention to connect with the artists who still visited the city in the middle of the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, the records of the Academy, which were available until 1940, became lost (Munro, Reference Munro1953: 42–3). However, the notarial deed through which, on 28 May 1850, Smith appointed ‘Lorenzo’ Macdonald as one of his proxies (the other one being Costa) hints at a proximity to Lawrence Macdonald (1799–1878), the Scottish sculptor who had been among those artists who had set about founding the British Academy of Arts in Rome.Footnote 49

One might wonder why Smith sold the property, and why he did so a few years after the acquisition from Mills and the efforts put into the improvement of the estate. His stay in the peninsula proved far from idyllic. Following the mourning of the couple in Venice, things did not get better in Rome, as regards both the volatile political situation and more private affairs. On 5 May 1851, Smith handed over to notary Luigi Hilbrat two love letters, written in Italian and addressed to Julia.Footnote 50 The two messages, in the same handwriting and opening with ‘My angel’ (‘Angiolo mio’) and ‘My soul’ (‘Anima mia’), were seemingly handed over as evidence of Julia's conjugal infidelity. Three days later, on 8 May, His Excellency Girolamo Odescalchi presented to notary Filippo Ciccolini a missive dated 25 February 1850.Footnote 51 Julia — ‘persecuted for eleven months without having committed any crime’ — seeks the written support of the cardinal vicar, who, she alleges, verbally expressed his conviction ‘that she had been unfairly mistreated in this unfortunate affair’.Footnote 52 The same folio includes the cardinal vicar's response to this plea, acknowledging that, while ‘the Ecclesiastical Authority had to take drastic actions against her last year due to unfavourable circumstances’, this made ‘her stand out for her wise conduct’ and showcased ‘how wrongly she was blamed for those shortcomings’.Footnote 53

The tale of the Smiths offers inspiration for a novel. I have located the burial place of the colonel at the very entrance (to the left) of Saint Michael the Archangel Churchyard in Teignmouth, Devon. The burial monument — with a rectangular base evolving into a delicate horizontal cross and displaying simple trefoil motifs — carries, on one side, the epitaph ‘In Memory of MARY SMITH. daughter of James and Mary Smith. who died January 29th 1872. Aged 83 Years. Also of ROBERT SMITH. C.B. son of James and Mary Smith. late Colonel of the Bengal Engineers. who died September 16th 1873. Aged 86 Years.’ and, on the other, ‘In Memory of MARY. the wife of James Smith Esq.r who died July 28th 1838. Aged 78 Years. Also of JAMES SMITH Esq.r who died March 9th 1839. Aged 99 Years.’ Robert was buried with his sister, alongside their parents. This hints at an attachment to his original family and the country where he grew up. It also suggests estrangement from Julia and their offspring. A will written in 1850 in Paris indicated his unmarried sister as the heir of his entire estate (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 105). In the late summer of 1851, he returned to Torquay, where Mary, following the deaths of their parents, had purchased a house on Warren Road (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 105). He acquired some five and a half acres of land in Paignton and embarked on the lavish construction of Redcliffe Towers (R. Head, 28 May Reference Head1981; James, Reference James, Finn and Smith2018). After the stay in Italy, he allegedly disposed of a significant sum and, after his death — occurring ‘at Florence Villa, Torquay, aged 86’ (Colburn's United Service Magazine, October 1873: 261) — his estranged son Robert Claude inherited £90,000 (as Mary had died shortly before her brother) (James, Reference James, Finn and Smith2018: 290, 295). According to The Law Times Reports (In the Goods of Co. R. Smith, 28 February 1874), Robert Claude ‘was formerly an officer in her Majesty's service, but he quitted it in 1864, under circumstances which incurred his father's displeasure’. In the letter to the cardinal vicar — demonstrating that, in early 1850, she was in peril of her future — Julia lamented being ‘deprived of all that is indispensable and of all that she had been enjoying since her childhood’.Footnote 54 After that, all trace of her is lost. R. Head (28 May Reference Head1981: 1524) has alleged that she had died by 1850. According to the Commissions and Inquisitions of Lunacy, the colonel was certified insane in 1872 (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 109). Would the tale of the Smiths offer inspiration for a crime fiction more than a romantic novel? The setting points towards a Gothic novel.

THE GORDIAN KNOT

In a circular letter from the Roman Monastery of Visitation dated 20 May 1859, Maria Agostina Del Monte, its 24th Mother Superior, commented that ‘the exterior [of the new house of the institute] is quite bizarre and peculiar’.Footnote 55 An albumen print by Tommaso Cuccioni, showing the hill from the Aventine a few years after the acquisition of the estate by the order, captures the rotunda of the villa emerging from the cypresses on the left — with its finials and hanging arches — juxtaposed to, and acting as a counterpoint to, the ruins of the Palatine Stadium and the Palace of Severus (Fig. 17). This albumen print — one of the earliest representations of the edifice in its neo-Gothic form — and the remark of the Mother Superior raise the question as to who was the patron of the medievalist renovation of the Domus Augustana.

Fig. 17. Tommaso Cuccioni, Il Palatino visto dall'Aventino, c. 1860, albumen print, 37 × 52 cm, MR, Archivio Fotografico, Fondo Cianfarani, AF — 22782. Courtesy of the Sovrintendenza Capitolina — Museo di Roma.

Jannattoni (Reference Jannattoni1987) has attributed this patronage to the ‘scozzese’ Mills, as if the makeover was an attempt to highlight his Scottish heritage. In doing so, he has drawn on a persistent and long-lasting trope, which can be tied to a passage of the chapter on ‘Scottish Memorials in Rome’ in Lanciani's New Tales of Old Rome (Reference Lanciani1901: 325–6). Here the archaeologist and collector mentions that ‘This Scotch gentleman caused the Casino … to be reconstructed in the Tudor style with Gothic battlements’, and notes that the gates of the estate showed ‘the emblem of the Thistle’. With the publication by the acclaimed pioneer in the study of Rome, the trope was canonized: Mills was Scottish and was behind the neo-Gothic intervention.Footnote 56 This is problematic on various levels. First, Mills's attachment to, and pride in, his Scottish descent is yet to be upheld by primary evidence.Footnote 57 Second, Smith might have been interested in manifesting the same attachment and pride, something which could explain the adjective ‘scozzese’ adopted by A. Rufini (Reference Rufini1857: 41) just a few years after the lieutenant-colonel's return to England. After all, his family claimed to have come originally from Scotland, and his son applied for Scottish arms in 1876 (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 84–5). Last but not least, Lanciani has failed to highlight that, as the photographic print of the British School at Rome shows, alongside a sculptured roundel with the thistle (on the gatepost to the right), the entrance from via dei Cerchi exhibited a roundel with the rose (on the gatepost to the left) (Fig. 18). Nor does he mention that the roundels upon the spandrels of the loggia of the villa showed the floral symbols of Scotland and England, but also the shamrock of Ireland — either separately or in conjunction — and a mounted Saint George (England's patron saint) killing the dragon (Fig. 19). More than a ‘Scottish’ patronage, the renovated villa can be seen as an architectural attempt to embrace and showcase a national identity of the British Isles. Acting as a nationalistic banner of the Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in Italy, the neo-Gothic intervention might convincingly be traced back to the British phase of the estate (sometime between 1818 and 1855).

Fig. 18. Detail from John Henry Parker, Palatine, between 1864 and 1866, photographic print on card, image 19 × 26, on card 22 × 30 cm. Rome, BSR PA, John Henry Parker Collection, jhp-0108. Courtesy of the British School at Rome.

Fig. 19. Selection of roundels from the northeast loggia of Villa Smith, Rome. Details from photographic prints on card of the Soprintentenza alle Antichità Palatino e Foro Romano. Rome, ASPArCo, Archivio Fotografico, Villa Mills, VM-FN (the three flowers in conjunction and the thistle: 020-asf022639; the rose: 008-asf022625; the shamrock: 013-asf022630; Saint George: 002-asf022617). Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Parco Archeologico del Colosseo.

Despite common misconceptions and enduring assumptions, neo-medieval architecture was a remarkable phenomenon in pre-unification Italy, which mirrored the anxieties and challenges of the Age of Revolutions, and the ambitions of the Risorgimento. Yet if the Gothic Revival remains a sporadic anomaly in Rome, it was even more sporadic there prior to its ‘Capture’ in 1870. In the capital of the Papal States more than in other Italian contexts, one could underline a meaningful resistance to the Gothic Revival. The villa on the Palatine is thus a curious, if exceptional, case. The Gothic Revival also manifested in pre-unification Rome at Palazzo Torlonia and Villa Torlonia as part of the interventions commissioned from G.B. Caretti (Checchetelli, Reference Checchetelli1842: 13–14, 47, 56–7, 76, 82, 85–6), in G. Vantaggi's design for the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus at Villa Lante (1843) (Angeli, Reference Angeli1902: 123) and in G. Bianchedi's refurbishment of the Basilica of Saint Mary above Minerva (1848–55) (Del Tempio, 1855). Yet in these cases the neo-Gothic is hidden from view in the cityscape of Rome as it is limited to the interiors; whereas the Gothic Revival was recognizable from a distance in the case of the British villa, and exhibited on a hilltop in the heart of the Eternal City. A peculiar choice for Rome, the neo-Gothic design can be seen as a meaningful signifier of ‘Britishness’ — an operation which E.W. Pugin later reiterated in Rome in his (unrealized) design for the collegiate chapel of Saint Thomas of Canterbury, commissioned in 1864 by the Venerable English College (Richardson, Reference Richardson2007). While ‘acclimatizing’ the British Gothic Revival to Rome, the villa on the Palatine explicitly referenced the ‘Orient’. Orientalist architecture was by no means exceptional in Italy. In Rome itself, orientalism and medievalism coexisted in G. Jappelli's designs for the gardens of Villa Torlonia (Checchetelli, Reference Checchetelli1842: 92–7). Yet through the intertwining of Indian aesthetic and British symbolism (in the form, for instance, of the Mughal arches and the floral emblems, respectively), the villa on the Palatine can be framed as a potent nationalistic initiative (see Figs 4, 5, 19). It sheds new light on British imperialist fantasies and underpins how these, while extending far beyond the borders of the formal/informal empire, reached the cradle of the Roman Empire.

While it is unlikely that ‘Classic Gell’ was into medievalism and orientalism, at least to the extent of embarking on a large-scale renovation — something that he probably could not even afford — the Middle Ages and the Orient held a fascination for a certain Mills, as witnessed by the publication of An History of Muhammedanism (Reference Gell and Gandy1817), The History of the Crusades (Reference Mills1820) and The History of Chivalry (Reference Mills1825). Yet the author of these works, whom some have confused with our Charles Andrew Mills, was the English historian Charles Mills (1788–1826) from Croom's Hill, Greenwich. The son of Peter Matthew Mills ‘of Twickenham’, where Horace Walpole had completed his Strawberry Hill (1749–76), it is tempting to imagine Charles Andrew growing fascinated by (what has been consecrated as) the dazzling wellspring of the Gothic Revival.Footnote 58 Yet the dominating symmetrical design — which reveals an attempt to instil order into an otherwise irregular site — the prominence of the central rotunda, and the direct quotations from India make the neo-Gothic villa of the Palatine visually less close to Walpole's asymmetrical compound than it is to the mansions that Smith, after selling the property in the Papal States, realized in England and in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia (in today's France) (Figs 20 and 21).Footnote 59 The so-called ‘Redcliffe Towers’ in Paignton (1852–64) (James, Reference James, Finn and Smith2018) and the ‘Château de l'Anglais’, ‘Château de Mont Boron’ or ‘Château Smith’ in Nice (1856–73) (Didier-Moulonguet, Reference Didier-Moulonguet1978; Gayraud, Reference Gayraud2011) provide durable evidence that Smith joined the architectural currents of medievalism and orientalism, and hint at his involvement in the makeover of the villa on the Palatine. It can be hypothesized that this villa, which recalls the architecture of the Indian subcontinent, and his own architectural work in that context, was not just the result of the patronage but also the design of the British official. Despite the sporadic references to Smith in connection with the Roman estate, some authors have (briefly) hypothesized his involvement. James (Reference James, Finn and Smith2018: 287) has noted that ‘it seems likely that the design of the new additions to the Villa Mills was by Smith, not Mills’. According to Garcia Barraco (Reference Garcia Barraco2014: 33–4), instead, Smith added orientalist features to a pre-existing neo-Gothic edifice by Mills. Yet no primary evidence has been provided to support such hypotheses. One could also argue, for instance, that Mills was the patron of the neo-Gothic refurbishment and that Smith later reiterated the forms of the Roman villa in Paignton and Nice. Shorto (Reference Shorto2018: 102–3) has suggested that the double-sided loggia was an addition by Mills and that ‘Smith purchased the house because it reminded him of Delhi, not that he altered it to look more like Delhi.’ To sustain this, she has claimed that Smith did not invest any money in major additions and that there are no requests on record to alter the house (Shorto, Reference Shorto2018: 103).

Fig. 20. Redcliffe Towers, Paignton. Mr Smith's House, Paignton, c. 1880 (presented to King George V when Duke of York, 7 November 1892), albumen print on card, 8.2 × 8.4 cm (image). London, RCT, RCIN 2584447. Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023.

Fig. 21. Château Smith, Nice. Chateau Mont-Boron, late nineteenth century, cabinet card, 10.8 × 16.4 cm. Courtesy of the author.

Let's go back to the photographic print in the Parker Collection and zoom in on the gateposts (see Fig. 18). Construction permits and building-related documentation are valuable sources for determining the patronage, construction phases and author of architectural renovations. Unfortunately for those interested in architectural history (and luckily for the patron of the medievalist makeover of the Palatine), home renovations in the nineteenth century did not require the same amount of paperwork and permits that are requested today. Yet one thing the municipality of Rome particularly cared about was works that would have some kind of impact on public spaces, such as streets. As previously discussed, the submission of a formal request to build the entrance in via dei Cerchi has enabled the attribution of the gate to Smith. Through a visual comparison between the two roundels (one with the rose; the other with the thistle) on the gateposts of that entrance and those on the spandrels of the neo-Gothic loggias of the villa, a convincing case can be made that Smith, rather than Mills, was responsible for the medievalist–orientalist renovation (see Fig. 19).

The patronage of the neo-Gothic makeover can be confirmed through groundbreaking archival documentation. In the notarial deed for the sale of the estate to the nuns, notary Camillo Diamilla officially reported, indeed, that ‘Mr. Colonel Smith [employed] a vast sum in building and decorating works to transform the little house into a noble palace, including the commission of various embellishments, ornaments, decorations, and extensions, as well as the rich, vast, and fleeting arcades.’Footnote 60 The neo-Gothic villa that once incorporated the Domus Augustana, known as ‘Villa Mills’, can be renamed ‘Villa Smith’.

FRAMING (VILLA) MILLS

Mills is buried in the Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome, in the Zona Vecchia (Shelley's section), gravestone S177, plot eighteen in the twelfth row. The rectangular grave is in an advanced state of decay and the epitaph — reported in the database of the cemetery as ‘CHARLES ANDREW MILLS ESG. [sic] 1846’ — was illegible during my visit, save for the Chi Rho symbol (of victory over death).Footnote 61 Scherer (Reference Scherer1955: 124) has described the tomb as ‘an inconspicuous flat stone’ and has remarked that only the epitaph recalls ‘the eccentric Scot whose memory still haunts the halls where Domitian once held court’. A sense of disappointment is recognizable in Jannattoni's (Reference Jannattoni1987: 316–17) description of the tomb and epitaph, which ‘do not spring any surprise’ (‘Ma la tomba, e relativo epitaffio, non riserbano davvero alcuna sopresa’). Yet strikingly surprising is the visual contrast between, on the one hand, the simple gravestone and, on the other, the elaborate neo-Gothic villa that for long has been considered the patronage of Mills. While Mills was not behind this lavish, if self-absorbed, intervention, he was, interestingly, behind the choice for his own modest burial. ‘Should I die in Rome’ he wrote in his Italian will, ‘I want to be decently buried, but with no useless and expensive pomp.’Footnote 62 Enough emerges from this testament to sketch the profile of a much less eccentric Mills than the one that has been drawn in the literature — which has often (trivially) remembered him as a peculiar foreigner who threw parties above the Palace of the Caesars.

Mills's enclosure on the Palatine consisted of a narrow slip of ground, with the entrance being upon the short side on via S. Bonaventura (Fig. 22). The other short side followed the line of the southwest end of the hill. Its long sides, which followed the orientation of the imperial structures, neighboured the Orti Farnesiani, to the northwest, and the Palatine Stadium, to the southeast.

Fig. 22. Detail of the Rione X (Campitelli) from the urban cadastre of Rome (1818–24). Rome, ASR — SIS, Presidenza generale del censo, Catasto urbano di Roma, Rione X, Piante, Foglio II. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Archivio di Stato di Roma.

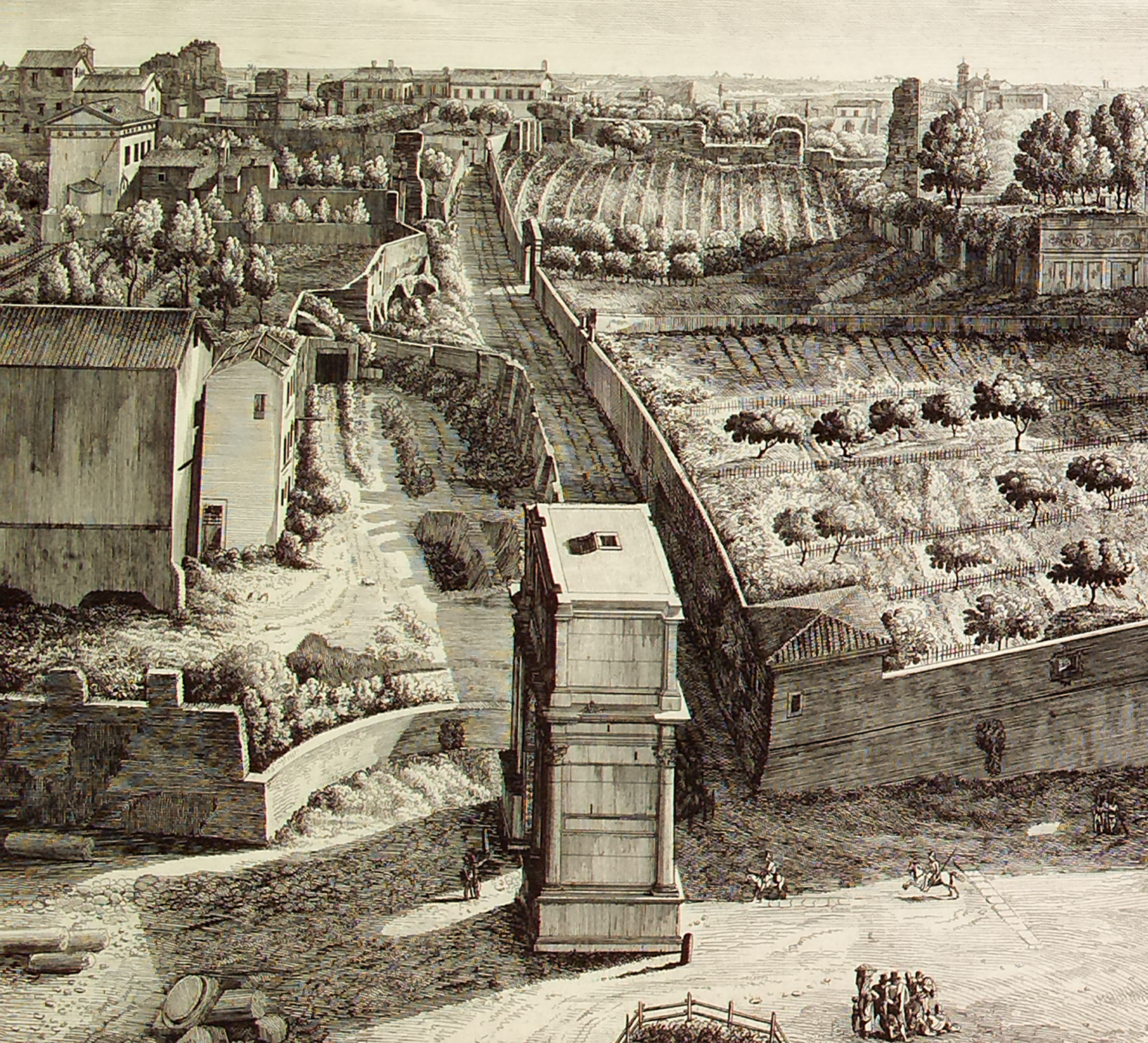

According to Nibby (Reference Nibby1827: 218), the location of the estate could be regarded as the most interesting in Rome due to the magnificent and extensive views and the ‘rimembranze antiche’ (literally, the ‘antique remembrances’). As depicted in a lithograph by Godefroy Engelmann (1788–1839), which offers a landscape view from the terrace in the western corner of the gardens, the property certainly offered a privileged viewpoint onto the surroundings, as well as onto the Roman past (Fig. 23). On the left, the southern boundary wall of the gardens leads towards the remains of the Palatine Stadium, passing through the same archway depicted in one of Charlotte Bonaparte's drawings of the area. The caption below the illustration reads ‘Vigna Palatina’ rather than Villa Mills. Indeed, it is not uncommon for sources from especially the first half of the nineteenth century to refer to the villa and the estate, respectively, as ‘Villa Palatina’ and ‘Vigna Palatina’ — as the area had been long associated with the Palatine vineyards. ‘In order to go to the Vigna Palatina, or Mr. Mills's villa,’ G. Head wrote (Reference Head1849: 68),

it is necessary, after leaving the entrance of the Ort Farnesiani, to advance farther up the Via di Polvereira [sic] … [A]fter proceeding a short distance the way suddenly inclines at a right angle to the left, or southward, towards the convent and little church of S. Buonaventura, where the road terminates by a cul de sac. Here, on the right-hand side immediately before arriving at the church and convent is the entrance of the Vigna Palatina.

(see Fig. 22). The name ‘Vigna Palatina’ was reported to appear at the entrance to the gardens (Nibby, Reference Nibby1827: 217).Footnote 63

Fig. 23. Godefroy Engelmann, Vigna Palatina, c. 1840, lithograph, 18.4 × 24.9 cm. Rome, BiASA, Archivio Rodolfo Lanciani, Roma XI.7.V.20, 17745. Courtesy of the Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell'Arte.

The remains of antiquity on the Palatine contributed greatly to the reputation of the property. ‘In addition to the natural beauty of the situation,’ G. Head (Reference Head1849: 70) wrote, ‘the classical reminiscences attached to the surrounding objects compose the principal attraction of the villa.’ Mills himself seems to have nurtured a particular interest in that heritage. According to C.I. Hemans (Reference Hemans1874: 204), ‘the most important among the scavi on the Palatine, in the present century, were directed by Antonio Nibby (1825–6) in the grounds of the Villa Mills’, as that ‘well known archaeologist was convinced that the ruins of the Augustan palace were here brought to light’. The same Nibby (Reference Nibby1827: 218) noted that the southern portion of the gardens, which, he alleged, rises entirely above the ruins of the house of Augustus, was the most delightful. Yet, in continuing that the ‘[early] modern embellishments’ (‘abbellimenti moderni’), in the form of (what today is known as) the Loggia Stati–Mattei, added to the prestige of the estate, he interestingly manifested appreciation for the non-antique heritage of the Palatine (Nibby, Reference Nibby1827: 218). The pictorial works did not fail to impress also the more critical G. Head (Reference Head1849: 70), according to whom the mansion ‘is only remarkable on account of its portico’. Most importantly, after ‘The neglect of the last owners of this garden had almost caused the loss of these beautiful paintings,’ Mills reportedly had ‘them restored with fine care by Camuccini, minus a painting that was deemed irremediable’ (Nibby, Reference Nibby1827: 219).Footnote 64 While suggesting that Mills similarly nurtured something of an interest in the heritage of the estate (broadly), this also interestingly attests that he put some effort into its preservation.

Entering the enclosure from via S. Bonaventura, and proceeding along an axial path through the gardens, one encountered the villa after covering about half the length of the site (see Fig. 22). I have located a hitherto unknown plan of Villa Mills among the illustrations comprised in architect Costantino Thon's (Reference Thon1828) work on the Palace of the Caesars, of which a copy is conserved at the Biblioteca Romana Sarti (Fig. 24). In the map depicting the ‘current state’ of the Palatine Hill, Thon included a floor plan of the villa in the ‘Giardino del Sig.r Mils [sic]’. The layout of the edifice was ruled by the pre-existing Roman structures it incorporated, as well as by its archaeological landscape. Visitors were welcomed by a passage which separated the west wing from the east wing. This passage led on to the ruins of the peristilium of the Domus Augustana and the southern portion of the gardens, which offered a special view of the surroundings. The villa followed the orientation of the Roman structures; it did not echo the axiality, symmetry and regularity of the imperial palace. The passage itself (today walled up) was not aligned with the centre of the Domus Augustana, and fell instead within its western portion. While the east wing was characterized by the Loggia Stati–Mattei, an L-shaped west wing reached out to the final section of the gardens. The irregular layout — that one could hypothesize as being the result of various building campaigns and adjustments — hints that the edifice was accommodated to the elaborate and multilayered site.

Fig. 24. Floor plan of Villa Mills. Detail from Costantino Thon, Pianta dello stato attuale del Palazzo dei Cesari, in Thon (Reference Thon1828). Rome, BRS. Courtesy of the Istituzione Sistema Biblioteche e Centri Culturali di Roma Capitale — Biblioteca Romana Sarti.

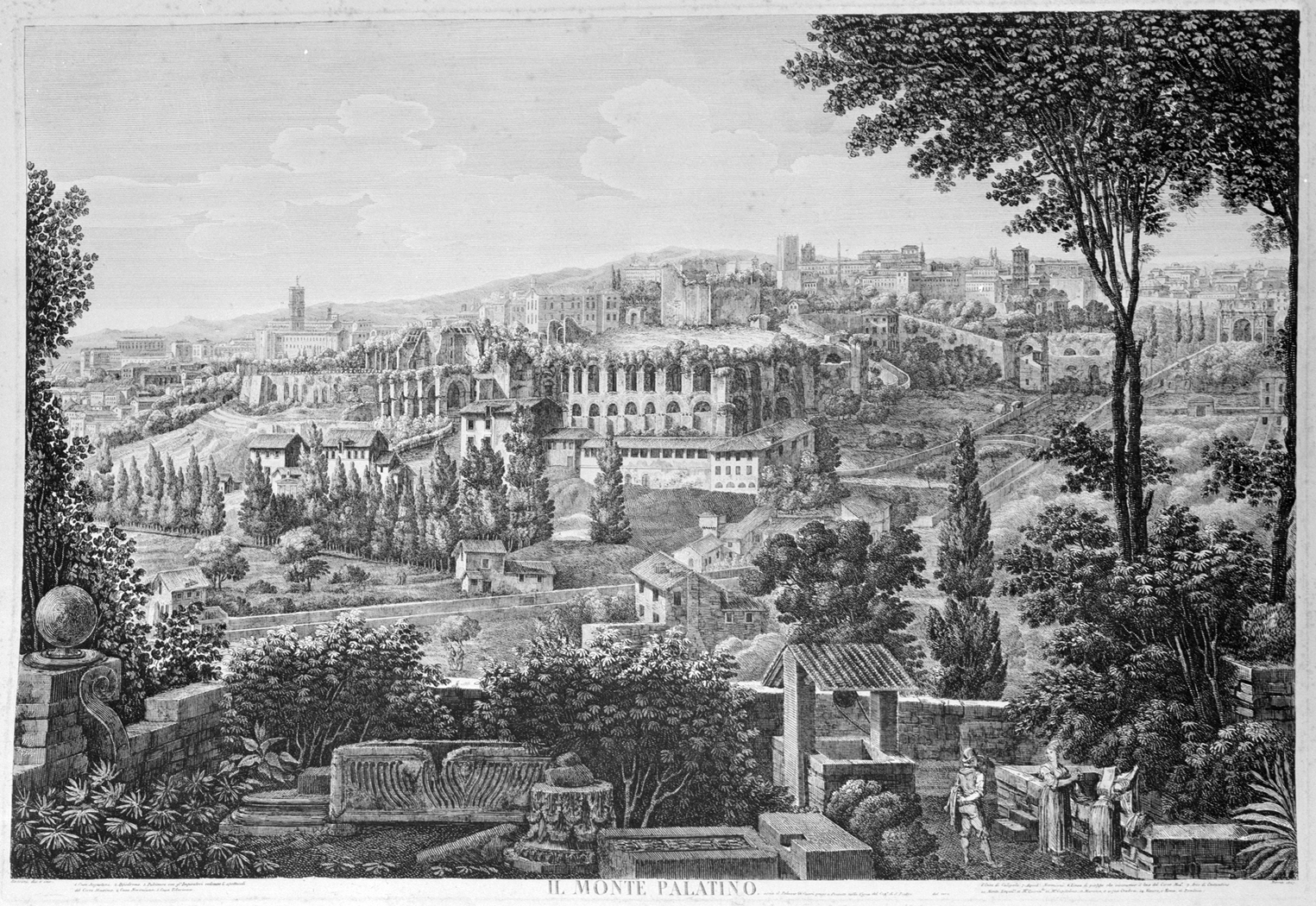

Similar conclusions might be drawn from an analysis of the visual sources offering depictions of the elevations of the villa — which, according to the Countess of Blessington (Reference Blessington1839: 470), was ‘arranged with exquisite taste’. The prints of Luigi Rossini (1790–1857), a prolific artist from Ravenna and one of the great illustrators of the marvels of the Eternal City, are precious instruments for the study of modern Rome (Luigi Rossini, 1982; Rossini, Reference Rossini2019), as they are for the study of Villa Mills (Garcia Barraco, Reference Garcia Barraco2014: 61–3). His extremely detailed panoramic view from the campanile of Saint Mary ‘Nova’, attached to the monumental publication I sette colli di Roma antica e moderna (Rossini, Reference Rossini1828–9), includes Villa Mills (Fig. 25). A street leads uphill, from the Arch of Titus, in the foreground. Partially hidden from view, the villa can be spotted in the background, with pitched roofs, preceded by a rusticated gateway. In this panorama, Rossini depicts an irregular edifice which seemingly matches the general layout provided by the urban cadastre. This, added to the representation of the central passage leading to the back of the gardens, enables us to argue that the etching provides a realistic depiction of the estate owned by Mills. Much less realistic appears to be the depiction offered by an etching dedicated to the Palatine Hill viewed from the Aventine (Fig. 26). This print gives an idea of the extraordinary location of the estate on the imperial hilltop. Yet the villa, which is only vaguely sketched and seemingly idealized and monumentalized, hardly matches the location and layout documented in the urban cadastre.

Fig. 25. Portion of a panoramic view of Rome with Villa Mills in the background left. Luigi Rossini, Panorama di Roma dal campanile di Santa Maria Nova, 1827, etching, in Rossini (Reference Rossini1828–9). Rome, MR, Gabinetto delle Stampe, MR — 38918 c. Courtesy of the Sovrintendenza Capitolina — Museo di Roma.

Fig. 26. Luigi Rossini, Il Monte Palatino, 1827, etching, 55.8 × 81.5 cm, in Rossini (Reference Rossini1828–9). Rome, MR, Gabinetto delle Stampe, MR — 38930. Courtesy of the Sovrintendenza Capitolina — Museo di Roma.

A detailed lithograph by the French artist Jean Louis Tirpenne, dated around 1830, shows an edifice in a bucolic setting (Fig. 27). A woman and a man stand at the centre of the composition, near two towering cypresses. The caption of the print, below the names of the artist and of the lithographers (Lith. de Therry Freres), reads ‘Vigna Palatina.’ A visual comparison between this print and a photo of Villa Smith convincingly shows that the former provides a realistic view of a portion of the southwestern elevation of Villa Mills (Fig. 28).Footnote 65 On the right, a few steps lead towards a set of two doors to the edifice. The doors are topped by a pair of oval windows and, above these, a pair of squared windows. A gable with a single opening completes the elevation. The identification of the edifice represented by Tirpenne as Villa Mills can be strengthened through a comparison with a photo of Villa Smith during its demolition (Fig. 29). A few differences occur between the triumphal archway depicted in the print and the triumphal archway (of the passage connecting the two portions of the gardens) captured in the photo. Most notably, the round arch of the former is replaced by an ogee arch, an operation which can be attributed to Mr Smith. The general layout remains, nonetheless, the same.

Fig. 27. Southwest view of Villa Mills. Jean Louis Tirpenne, Vigna Palatina, c. 1830, lithograph, 18.1 × 24.5 cm. Rome, BiASA, Archivio Rodolfo Lanciani, Roma XI.7.III.20, 17716. Courtesy of the Istituto Nazionale di Archeologia e Storia dell'Arte.

Fig. 28. South view of Villa Smith. Giovanni Gargiolli, n.d., photographic print. Rome, ASGFN, E1944. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione.

Fig. 29. Southwest view of the Domus Augustana prior to the completion of the demolitions. Soprintentenza alle Antichità Palatino e Foro Romano, Villa Mills, portichetto barocco, August 1927, photographic print on card. ASPArCo, Archivio Fotografico, Villa Mills, VM-FN 042-asf022664. Courtesy of the Ministero della Cultura — Parco Archeologico del Colosseo.

Tirpenne's print provides a partial depiction of Villa Mills, as it includes the east wing (the one which housed the Loggia Stati–Mattei) and a portion of the central building, which was surmounted by a pitched roof. Yet, alongside Rossini's representation of the main front, the print suggests that Villa Mills did not resemble the venustas and pomp of the imperial palace, nor did it showcase the self-evident monumentality of Villa Smith. This visual analysis can be supported by textual evidence — in the form of G. Head's account (Reference Head1849: 70) — suggesting that the mansion was ‘on a very limited scale as regards dimensions’. Indeed, in one of the illustrations provided to illustrate the Roman Forum in E. Pistolesi's (Reference Pistolesi1841) description of Rome and its surroundings, the edifice can hardly be distinguished on the right end of the Palatine, in the shadow (Fig. 30). As modest as a house which incorporated the walls of an imperial palace can be, Villa Mills was considerably more modest than Villa Smith.

Fig. 30. View of Rome with Villa Mills in the background right. Gaetano Cottafavi, Foro Romano, in Pistolesi (Reference Pistolesi1841). Rome, BSR L, 600.389. Courtesy of the British School at Rome.

A visual antithesis to the latter, the former was strikingly different from the one that has been long assumed. The modesty of Villa Mills, contrasting with the wit of Villa Smith, allows for a proper revision of the character of Mills. The same applies to its Italianate design, which is diametrically opposite to the explicitly imperialist and ‘British’ dimension of the neo-Gothic villa. This is a dimension which does not sit well with Mills's unresolved issues with Britain after his dismissal from the post in Guadeloupe, nor with his public support of Caroline. An important aspect remains to be addressed: what is the legacy, if any, of Mills's tenure of the property on the Palatine Hill?

Let's go back to his Italian testament. Paradoxically, while the name ‘Mills’ still lingers on the Palatine, Mills's generic instructions to sell the villa after his death do not disclose any particular effort to keep his name attached to it. This, alongside the explicit intention to be buried ‘with no useless and expensive pomp’, hints that Mills was much more modest than has been assumed. It also leads to the hypothesis that he did not embark on an extravagant makeover of the edifice.