Social media platforms have emerged worldwide as important political arenas in the digital era. Legislators use social media to bypass traditional media, promote themselves, and create more personalized political communication with their constituents (Hermans and Vergeer Reference Hermans and Vergeer2013). Although in many ways online communication possesses the potential to improve dialogue between elected representatives and citizens, a growing number of reports point to an increasing level of online abuse targeting politicians (Amnesty International 2018; Frenzel Reference Frenzel2019; Inter-Parliamentary Union 2016; NDI 2019). Previous research has indicated that online harassment is not only a democratic problem but also a gendered problem insofar as women politicians appear to be particularly exposed: sexist slurs and gendered threats constitute a serious detriment to the online lives of political women (Bardall Reference Bardall2013; Krook Reference Krook2017).

However, only a small number of studies have systematically examined and compared the experiences of online abuse of men and women politicians (see Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan Reference Rheault, Rayment and Musulan2019; Ward and McLoughlin Reference Ward and McLoughlin2020). In addition, these studies have examined gender differences regarding exposure to abuse only on Twitter and not on other platforms where legislators may also be active. There is thus no comprehensive account that systematically compares men’s and women’s experiences of online abuse on a range of different social media platforms. As a result, we know little about the magnitude of online threats and harassment but also of the nature of this type of abuse and its potential consequences. We argue that it is not enough to merely state that online abuse is gendered if we wish to understand and tackle such abuse—it is essential to know how it is gendered.

The aim of this article is to analytically conceptualize gendered online abuse in terms of three dimensions—frequency, character, and consequences—and thereby provide a more comprehensive empirical understanding of its prevalence. As such, this approach is useful for increasing our understanding of how the frequency and type of online abuse are related to the well-being and political ambition of individual men and women (cf. Herrick and Franklin Reference Herrick and Franklin2019); it also contributes to the discussion of additional costs associated with political engagement for men and women (Shames Reference Shames2017). To test the usefulness of our conceptualization, we empirically explore the gendered dimensions of online abuse in the Swedish Parliament by comparing men and women MPs’ experiences of online abuse. Although Sweden is known worldwide as a champion of political gender equality, little is known about the online abuse that targets politicians and whether it is gendered in this particular context.

We draw on unique quantitative and qualitative data from the Swedish Parliament derived from a survey of legislators and 48 interviews with men and women MPs to demonstrate that online abuse is gendered in different, and sometimes unexpected, ways. First, we find on the basis of our survey data that women do not experience more online abuse than men. On the contrary, a larger percentage of men have experienced direct threats online at least once. Yet women are slightly overrepresented among those who experience online abuse very frequently. Second, men and women are targeted by different types of abuse. Whereas men tend to be targeted in their role as politicians, women MPs are often targeted as women; they are subjected to more sexualized and gendered harassment. Third, the consequences of this abuse are gendered insofar as men exposed to high levels of online abuse seem slightly more inclined to leave politics, whereas women report that they feel that their personal agency is circumscribed to a greater extent.

These findings cast light on the complex and multidimensional nature of gendered online abuse, and they demonstrate the merit of unpacking the analytic dimensions of such abuse. This article not only contributes new empirical knowledge of the Swedish case but also provides insights of relevance beyond the Swedish context regarding issues in need of further theoretical exploration, such as the gendered link between the character of abuse and its consequences.

Gendered Aspects of Political Violence and Abuse

Despite the increasing share of women politicians worldwide over the past few decades, politics is often described as a male-dominated sphere permeated by a culture of masculinity that originated in a time when politics was an all-male business (Crawford and Pini Reference Crawford and Pini2010; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005; Rai and Spary Reference Rai and Spary2018). As women enter politics, they are confronted with this preexisting culture, viewed as “space invaders” (Puwar Reference Puwar2004), and constrained in various ways by masculine-coded rules and norms, as well as sexist practices that obstruct their political work (Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005). Numerous empirical studies have found that women politicians are negatively influenced by such constraints in different aspects of their political work (e.g., Dittmar, Sanbonmatsu, and Carroll Reference Dittmar, Sanbonmatsu and Carroll2018; Goetz Reference Goetz, Goetz and Hassim2003; Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003; Kantola and Rolandsen Agustín Reference Kantola and Agustín2019; Rai and Spary Reference Rai and Spary2018; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal2002; Ross Reference Ross2002). Violence and harassment comprise the most severe forms of these obstacles.

An emerging body of research has begun to examine the gendered dimensions of violence and harassment directed against politicians (Bardall Reference Bardall2011; Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021; Krook Reference Krook2017, Reference Krook2020; Krook and Restrepo Sanín Reference Krook and Sanín2016). It recognizes that violence is not limited to physical violence, and that attacks against politicians can instead take a wide variety of forms. For example, Krook (Reference Krook2017, Reference Krook2020) and Krook and Sanín (Reference Krook and Sanín2016) list physical, psychological, sexual, economic, and semiotic violence as different types of violence that women (and men) in politics experience. Psychological violence, which aims to harm the target’s mental state and emotional well-being, has been found to be the most common form of violence against women in politics in several contexts (Bardall Reference Bardall2011; Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018; Bjarnegård, Håkansson, and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård, Håkansson and Zetterberg2020; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021). Furthermore, social media comprise the most common arena for such violence (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Herrick, Franklin, Godwin, Gnabasik and Schroedel2019).

Scholars have also begun to develop theoretical frameworks and approaches to better understand the gendered nature of political violence. Krook and Restrepo Sanín (Reference Krook and Sanín2020) claim that it is necessary to distinguish between the violence that is specifically directed against women in politics (termed “violence against women in politics” [VAWIP]) and political violence in general. Although VAWIP is related to political violence in a more general sense in that it seeks to distort the collective will, it is nevertheless distinct because of the bias against women serving in political roles that it reflects. Attacks on women in politics, ranging from sexist slurs to physical violence, have the potential to deter women’s political participation and effectively subvert the impact of women’s presence in politics. VAWIP also has distinct types of consequences because it targets already marginalized political groups and thereby reinforces gendered hierarchies by excluding women from political processes (Krook and Restrepo Sanín Reference Krook and Sanín2020).

In contrast to VAWIP’s focus on women in politics, Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020) develop a framework for understanding the gendered nature of political violence that includes men’s experiences as well. First, women are not the only ones who experience gendered attacks: men who deviate from masculinity norms and LGBTQ+ individuals are also targeted in gendered ways that may be motivated by a desire to preserve political power in the hands of hegemonic men. Second, gendered manifestations of political violence only become visible when the experiences of women and men (or other intersectional groups) are empirically compared (Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020). Comparing women with men can thus highlight the various gendered dimensions of violence (see also Baldez Reference Baldez2010; Beckwith Reference Beckwith2010).

To conceptualize gendered political violence and link the VAWIP approach to mainstream approaches for studying political violence, Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020) identify three key dimensions—motives, forms, and impacts—in which violence against politicians can be gendered. Gendered motives implies that women, non-normative men, transgender individuals, and other groups are targeted for gendered reasons, such as policing politics as a (hegemonic) male space. Gendered forms denotes the use of gendered means of attack, such as sexualized harassment, whereas gendered impacts refers to the subjective meaning ascribed to political violence by both the targets and the audience of violence.

We focus in this article on a particular type of political violence: online abuse. We draw on Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020) in arguing that it is necessary to conceptualize how online abuse is gendered by comparing men’s and women’s experiences. In contrast to their theoretical framework, however, which characterizes and distinguish gendered political violence from other types of violence (nonpolitical and nongendered violence), we propose three distinct analytical dimensions to empirically capture how online abuse is gendered. In line with Scott (Reference Scott1986), we understand gender as an analytical and relational category that is created and maintained in social processes. On the analytical level, we address gender both by comparing men’s and women’s experiences and by investigating how ideas about masculinity and femininity underpin certain types of abuse, including their consequences. Our analytical approach is straightforwardly developed for the purpose of guiding researchers who conduct empirical studies of gendered patterns in online abuse. We should note that, although the results of an empirical analysis guided by our framework can be used to discuss the gendered motives, forms, and impacts of this specific type of violence, our framework is designed to capture neither the broader impact of such abuse in general nor its underlying motives.

Conceptualizing Gendered Online Abuse Analytically

We posit that online abuse can be characterized as a form of psychological political violence that is both highly public and highly ingrained in the personal sphere. First, online abuse is more public than most forms of violence targeting politicians, because it is often intended not only to directly affect the person it targets but is also designed to be viewed by a wider audience, which amplifies its impact through its being shared and circulated (Krook Reference Krook2020). Social media can be a particularly effective barrier to women entering politics because of their capacity to rapidly spread derogatory accusations that play on double standards of morality and ethics concerning women and men (Bardall Reference Bardall2013). For instance, accusations of being unfeminine, sexually immoral, or a bad mother are often used in attacks against women politicians globally, and such messages are easily spread through social media (Bardall Reference Bardall2013).

Second, online abuse is also very ingrained in the personal sphere because it reaches its targets through accounts that are often used for both personal and professional matters; these accounts are on mobile phones that typically follow MPs everywhere at all hours. As such, perpetrators of abuse can use social media to demonstrate their presence in politicians’ personal spheres, rendering them targets who possess very limited opportunities to distance themselves from such abuse. For these reasons, online abuse possesses a great potential to exert a damaging—and gendered—psychological impact on its targets. Moreover, social media provide potential abusers with readily accessible tools to exercise their abuse, usually with no risk of sanctions.

In this discussion, we conceptualize gendered online abuse in respect to three analytical dimensions to empirically capture whether and how it is gendered. The first dimension captures the frequency of online abuse and whether men and women are exposed to different amounts of abuse online. Although reports show that both men and women are exposed to online abuse to an increasing degree (Amnesty International 2018; Frenzel Reference Frenzel2019; Inter-Parliamentary Union 2016; NDI 2019), there are indications that women politicians are more exposed than men to this form of political violence (Bardall Reference Bardall2013; Krook Reference Krook2017; Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan Reference Rheault, Rayment and Musulan2019). We maintain that the frequency and magnitude of abuse directed against a particular group, such as women rather than men, are crucial pieces of information about its gendered nature, regardless of any motives or subjective interpretations associated with it. For instance, if a certain group faces more abuse than others, this inevitably elevates the cost of political participation for that particular group and consequently serves to obstruct equal representation both directly and indirectly.Footnote 1 As such, comparisons between the exposure of groups of men and women to online abuse are essential because, even if women are attacked on a very large scale, we cannot convincingly conclude that this constitutes a gendered pattern without comparing it to the frequency of attacks that men face. On the basis of previous research findings, we expect women to be targeted with more online abuse than men.

The second dimension, the gendered character of online abuse, highlights the importance not only of distinguishing between different types of abuse but also of the words and tropes used in that abuse. Regardless of whether the frequency of abuse is gendered, men and women might still be exposed to different types of online abuse, such as threats of violence, harassment, or offensive comments. Analyzing the gendered character of abuse may also reveal gender cues, such as remarks of a sexualized nature or comments related to motherhood or immorality (see Bardall Reference Bardall2013). A small number of studies conducted within the context of the British Parliament have found that British male MPs receive a higher share of abusive replies on Twitter than their women colleagues do. Yet women MPs receive more hate speech—abusive Tweets linked to the particular group to which the MP belongs and based, for instance, on their gender, sexuality, or ethnic background (Gorrell et al. Reference Gorrell, Greenwood, Roberts, Maynard and Bontcheva2018; Ward and McLoughlin Reference Ward and McLoughlin2020). It is important to explore not merely the amount of online abuse but also its character, because the latter may have different consequences for the victim. For example, research has found that perpetrators can make effective use of gendered and sexist cues to tarnish the reputation and image of women politicians (cf. Bardall Reference Bardall2013). On the basis of previous research, we expect to find that men and women are targeted with different types of online abuse, with women being more exposed to comments that are gendered and sexist in nature.

The third dimension, the gendered consequences of abuse, addresses the consequences that online abuse has for its individual targets, who in the current case are politicians. Regardless of the broader impact and meaning ascribed to such incidents in political discourse,Footnote 2 those directly targeted by online abuse may be affected on a psychological level and thereby their capacity to function as MPs may be impeded. In a study of mayors in the United States, Herrick and Franklin (Reference Herrick and Franklin2019) show that experiences of violence have a negative impact on their psychological health and careers, with the impact varying in accordance with the type and frequency of violence. Mayors who experienced harassment were more likely to report psychological harm than those who experienced other types of violence, such as physical violence or threats of violence. The frequency of exposure was also found to be a significant factor, leading the authors to conclude that “what may have the most significant effects on ambition are the constant attacks that wear down mayors” (Herrick and Franklin Reference Herrick and Franklin2019:2056).

Furthermore, the precise consequences that politicians experience may differ depending on their gender. Men and women politicians may react to and perceive abuse in different ways because of the power hierarchies and the gendered informal institutions and norms that exist in the surrounding society. In a study of the political ambitions of young people in the United States, Shames (Reference Shames2017) found that the perceived costs of running for office differed between various groups of men and women due to the additional costs that factors such as sexism pose for women and women of color. Consequently, it is important to investigate whether men and women are affected by online abuse in different ways, regardless of gender differences in the frequency and character of online abuse. Insofar as knowledge is limited concerning the individual consequences of online abuse, including whether certain types of abuse generate different consequences, it is difficult to stipulate a priori how consequences may be gendered (i.e., whether and how men and women are affected in different ways). We nevertheless expect not only that the types and frequency of abuse matter for the consequences but also that the consequences are gendered.

In summary, we argue that these three analytical dimensions of online abuse—its frequency, character, and consequences—provide a comprehensive perspective of the ways in which online abuse can be gendered. Our analytical framework can be used to obtain more fine-grained and nuanced empirical knowledge in this regard and reveal contextual specificities in respect to gendered conditions in politics. In addition, it provides a basis for a deeper theoretical understanding of gendered online abuse. Studying each dimension in isolation provides valuable knowledge, and none should be viewed as more important than the others. We nevertheless argue that the questions of whether and how online abuse is gendered and the extent to which social media comprise an arena for violence against women in politics are best approached by taking into account all three dimensions and the relationships between them.

The Case of Sweden

Sweden is ranked as one of the most gender-equal societies in the world,Footnote 3 and the country is often regarded as a champion of political gender equality. The Swedish Parliament has been numerically gender equal for almost three decades, and its internal work is characterized by the explicit ambition to attain equal working conditions for men and women MPs (Freidenvall and Erikson Reference Freidenvall and Erikson2020; OSCE 2013; Palmieri Reference Palmieri2011). Despite deliberate efforts in this area, however, gender equality could potentially be undercut by violence against women in politics that circumscribes their political careers. Although political violence always constitutes a democratic problem, it might also comprise a gendered problem if either women or men are particularly affected.

Violence against politicians has become an increasing problem in Swedish politics. According to survey data from a large number of Swedish politicians at both the local and national levels, 30% of elected politicians experienced violence, harassment, or threats in 2018, up from 20% in 2012. An important part of this violence involves online abuse, a form of violence that has been increasing over time (Frenzel Reference Frenzel2019). New research based on survey data on local-level Swedish politicians indicates that women are particularly exposed to political violence at all levels (rank and file, committee chairs, and mayors); exposure to violence increases at higher levels of the political hierarchy; and the gender gap in exposure to violence increases in accordance with the level of power (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021). Although there are few studies of online abuse targeting politicians in Sweden, a recent report found that women politicians are more exposed than men to offensive comments on a certain popular online discussion forum (flashback.org) and that only women were exposed to comments that allude to sexuality (Fernquist et al. Reference Fernquist, Kaati, Pelzer, Lindberg, Akrami, Cohen and Sarnecki2020).

Given Sweden’s ambitious gender equality work, investigating online abuse directed against politicians in this country provides insights that are also relevant for other contexts where efforts are underway to attain gender-equal political participation. Knowledge about whether and how online abuse is gendered is important if we wish to understand and evaluate men’s and women’s substantive representation and their political ambitions. In addition, lessons drawn from the Swedish case might also contribute more broadly to advancing theory concerning obstacles to gender-equal political representation.

From a methodological point of view, characteristics of the Swedish context facilitate an investigation of the multidimensional character of online abuse, including its gendered nature. The combination of a high level of social media usage among MPs,Footnote 4 the large proportion of women in Parliament, and the substantial group of women MPs who are comparable to men MPs in terms of background and positions provides an important advantage when studying gender differences in online abuse.

Data and Methods

Because online abuse has only recently emerged, there are no widely accepted conceptual definitions of online abuse or online violence against women.Footnote 5 We focus in this article on attacks against legislators that take place on social media, and we differentiate between direct threats and offensive comments when possible. In addition, we specifically analyze offensive comments of a gendered or sexualized character.

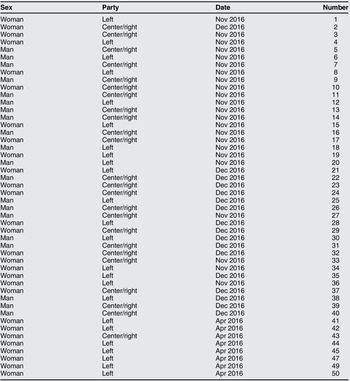

To explore whether men and women MPs experience online abuse differently, we draw on survey and interview data collected from the Swedish Parliament. To take stock of MPs’ experiences of the Swedish Parliament as a workplace, we designed a survey that includes several items related to online abuse, primarily this question: “How often have you experienced: a) Offensive comments, b) Direct threats, c) Comments related to gender/sexuality on social media?” The respondents were asked to rate the frequency of such experiences on a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (very often). The survey also includes a question concerning how often MPs have considered resigning from parliament, which we used to explore the potentially gendered consequences of abuse. We conducted the survey in January 2016, to which 287 of 349 MPs responded, yielding a response rate of 82%. The respondents were generally representative of the group of MPs as a whole, with 81% of the women and 83% of the men completing the survey (see table A2 in the online appendix).

In addition to the survey data, we conducted interviews with 48 MPs to further explore the character and potential consequences of online abuse. A first set of interviews in November and December 2016, which lasted between 40 and 90 minutes, involved 20 men and 20 women MPs from all eight political parties in parliament at the time. The interviews centered on legislative working conditions in general, but social media usage and experiences of online abuse comprised one of the eight themes addressed in greater detail.Footnote 6 The strength of these interviews is that we can compare men’s and women’s experiences in a reliable way and thus explore potential gender differences. A second set of interviews was conducted in April and May 2019 with eight women MPs who reported a high level of social media usage. The aim of this second group of interviews was to gain a deeper understanding of how gendered abuse is manifested. Respondents are not named but instead are randomly identified with numbers to ensure confidentiality (see table A3 in the online appendix for a list of respondents).

Although self-reported data about experiencing online abuse may be viewed as less reliable than, for example, analyzing public Twitter data, it has three main advantages. First, it covers all online abuse experienced by politicians from every social media platform used. As such, it represents an all-encompassing approach in comparison to studies that only analyze abuse on one platform. Second, asking MPs about their experiences makes it possible to obtain information on key aspects of social media that are not publicly available. Private messages and Tweets that have been deleted due to their offensive content are examples of highly relevant data that are unavailable using research designs that rely on public social media data. Third, studying how targets experience online abuse is absolutely crucial if we are interested in how they react to such attacks and what consequences they have for the individual politician. For example, analyzing abusive Tweets that mention the name of a certain politician is less relevant in this regard because we do not know whether the target of this violence was in fact aware of it.

An important issue that must be accounted for in analyzing all forms of violence against politicians—not just online violence—is who is most vulnerable to attack. This is not only a theoretically important question but is also methodologically relevant for study design. Key findings in this regard are that young politicians in general (Collignon and Rüdig Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Herrick, Franklin, Godwin, Gnabasik and Schroedel2019), and young women in particular (Erikson and Josefsson Reference Erikson and Josefsson2021), are more exposed to violence and that a politician’s gender intersects with party membership to create increased vulnerability (Kuperberg Reference Kuperberg2018). Furthermore, not only are gender differences most pronounced among the most powerful and visible politicians (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021; Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan Reference Rheault, Rayment and Musulan2019) but well-known politicians also receive more online abuse (Gorrell et al. Reference Gorrell, Greenwood, Roberts, Maynard and Bontcheva2018). Consequently, our models include controls for factors that have been found to be important in previous research, enabling us to compare women and men who are as similar as possible in other relevant respects. For example, we take power and visibility into account by controlling for frontbencher and newcomer status. In addition, we include a dummy variable for MPs who are 35 years of age or younger in all our models to account for previous findings that suggest that young legislators comprise a particularly exposed group.Footnote 7

Our empirical approach to capturing online abuse thus provides a comprehensive account of the abuse MPs experience online and how they react to this type of violence.

Results

Gendered Frequency of Online Abuse

Are women MPs more exposed to online abuse than men MPs? In our 2016 survey, we asked legislators how often they experienced (a) direct threats, (b) offensive comments, and (c) comments associated with gender/ sexuality on social media, on a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (very often). Overall, 93% of the men and 95% of the women reported having experienced at least one form of online abuse at least once (a nonstatistically significant difference).

Regarding direct threats, we found that 73% of the legislators, a large majority, experienced direct threats on social media. Contrary to our expectations, however, more men than women (78% vs. 67%) reported that they had experienced a direct threat on social media at least once—a statistically significant difference.Footnote 8 This is noteworthy in relation to previous research, which suggests that women are more likely to experience this type of abuse. However, no statistically significant gender gap emerges when comparing mean values concerning how often men and women experience such threats. The average value for men reporting direct threats is 2.7 on a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (very often), whereas the corresponding value for women is 2.5 (a one-tailed t-test reveals a p value of 0.735).Footnote 9 In addition, although women are overrepresented among those who lack exposure to this type of abuse, a slightly larger percentage of women than men are in the group of MPs who are most exposed to direct threats. However, the difference in the proportions of men and women who often experience direct threats is not statistically significant (a chi-square test reveals a p value of 0.298; figure 1).

Figure 1 Direct Threats

Note: How often have you experienced direct threats on social media? (Scale from 0, never, to 10, very often). Here 0 = never; 1–3 = seldom; 4–7 = regularly; 8–10 = often/very often.

In respect to the second form of online abuse, offensive comments, more than 90% of MPs have received an offensive comment on social media at least once. Once again, contrary to our expectations that women would be more exposed to online abuse, no statistically significant gender gaps emerge for this survey item. First, there is no significant difference in mean values between men and women (4.6 vs. 4.9; a one-tailed t-test reveals a p value of 0.212).Footnote 10 As is the case with exposure to direct threats, we find women to be slightly overrepresented in the group that has experienced offensive comments often or very often, but they are slightly underrepresented in the group that has never experienced offensive comments online (figure 2). None of these gender differences is statistically significant, however.Footnote 11

Figure 2 Offensive Comments

Note: How often have you experienced offensive comments on social media? (Scale from 0 – never, to 10 – very often). Here 0 = never; 1–3= seldom; 4–7= regularly; 8–10= often/very often.

Finally, 46% of the men and 79% of the women reported receiving comments associated with gender and/or sexuality at least once, which is a statistically significant difference (p = 0.000). However, women appear to be much more intensively targeted than men in the group of MPs who reported having received this type of comments (figure 3). The mean for women reporting comments associated with gender and/or sexuality is 3.4 on a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (very often), whereas the mean for men is 1.2. This is a highly significant statistical difference (a one-tailed t-test reveals a p value of 0.000). Seventeen percent of the women, but only one man (0.6%), have been exposed to these types of comments often or very often (a chi-square test reveals a p value of 0.000).

Figure 3 Comments Linked to Gender, Sexuality, or Both

Note: How often have you experienced comments linked to gender/sexuality on social media? (Scale from 0 – never, to 10 – very often). Here 0 = never; 1–3 = seldom; 4–7 = regularly; 8–10 = often/very often.

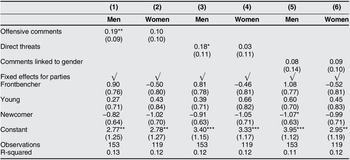

Table 1 presents exposure to different forms of online abuse for men and women using OLS regressions. The dependent variable is the level of exposure, ranging from 0 (never exposed) to 10 (exposed very often). No statistically significant differences between men and women were found for offensive comments or direct threats in the bivariate regressions nor when we included fixed effects for political parties and controlled for individual-level characteristics. However, women’s greater exposure to comments linked to gender/sexuality is statistically significant both in the bivariate regression (column 5) and when we add fixed effects for political parties and control for such individual-level characteristics as being a newcomer, a frontbencher, or young (column 6).

Table 1 Gender Differences in Exposure to Three Forms of Online Abuse

Note: How often have you experienced a) offensive comments, b) direct threats, c) comments linked to gender and/or sexuality on social media? Scale from 0, never, to 10, very often. Woman reports the difference between women and men. FE reports fixed effects; Frontbencher reports the difference between MPs with and without a frontbench position in Parliament. Young reports the difference between MPs who are 35 years of age or younger and those older than 35. Newcomer measures the difference between MPs serving their first term in Parliament and those with greater experience. Standard errors in parentheses: *** p<0.01, ** p <0.05, * p <0.1.

Contrary to our expectations, women do not appear to be more exposed to online abuse than men on the basis of this survey data. On the contrary, more men than women reported having experienced direct threats and offensive comments online at least once. However, even though women are underrepresented in the group of MPs who have never experienced direct threats, they are slightly overrepresented in the group of MPs who are exposed to online abuse often or very often. These findings also indicate that there is a substantial difference within the group of women, where some MPs are particularly exposed. Furthermore, although many of the survey respondents have personal experience of several types of online abuse, there is also a clear indication that women are exposed to a particular type of “gendered abuse” in addition to “general” online abuse. The frequency of online abuse experienced by men and women does not appear to differ greatly when we simply compare mean values. However, our analysis of the third form of online abuse that we have captured with the survey data—comments linked to gender/sexuality—indicates that the character of online abuse experienced by men and women may be gendered. We use our interview data with men and women MPs to explore our second dimension: the character of gendered online abuse.

Gendered Character of Online Abuse

Briefly stated, and in line with our survey findings that women are more exposed to gendered and sexualized comments, we find men to be targeted online mainly in their roles as politicians on the basis of our analysis of the interviews, whereas women are targeted to a much greater extent as women or as sexualized beings. In addition, we identify five types of online abuse in the accounts that surfaced in the interviews. First, respondents point to generally unwarranted or impertinent comments (R27, R9, R36, R30, R23, R39) that may be described as involving “unpleasant, impertinent language, and argumentation” (R27). A second type of abusive comments is related to the competence or capability of an MP (R25, R8, R36, R10, R32, R15, R6, R11, R21, R39, R35, R34, R37, R24, R12). A typical example would be “comments that question whether I should have a position in Parliament at all” (R5). A third type is of a more personal nature and relates to an MP’s looks or physical appearance (R20, R22, R6, R12, R21, R32), such as comments about being “fat, greasy, and ugly” (R41). A fourth type consists of more severely abusive comments that can often be described as verbal harassment, often associated with gender (R25, R10, R32, R14, R3, R13, R29, R28), sexual orientation (R4), or ethnic background (R26, R13, R1, R15). A fifth type of online abuse comprises threats of violence in the strict sense (R34, R18, R23, R3, R37, R14).

Although most legislators reported that the tone of social media is often harsh and unpleasant, with a significant number having regular experiences of online abuse, direct threats of violence tended to be limited. MPs of both sexes appeared to be rather accustomed to unwarranted comments and comments that target their competence as politicians. These types of comments are directed toward the MP in his or her role as a politician in contrast to comments that are more personal in nature and center on an MP’s appearance, gender, sexuality, or ethnicity. The interview data indicate that women experience the latter type of personal comments much more often than men and that such comments often constitute a type of abuse that is gendered in its content.

When we focus on the type of abuse that the group of women MPs experience, a first finding is that women appear to be much more frequently subjected to comments associated with their appearance than men. Although these comments are not always negative, several women respondents noted that they often turn into critique and abuse:

There is something about women’s appearance—unfortunately it often turns into nasty comments… and that is the starting point for a tone that is not positive. Men rarely get these kinds of comments (R22).

A second issue that stands out as typical for the abuse that targets women—and which is even more problematic—is that women appear to be regularly exposed to more severe forms of online harassment that use sexist language. A large majority of the women interviewed—more than two-thirds—maintain that they have received comments that target them as women rather than as politicians. In contrast, it is rare to find men who have experienced comments that sexualize them or are associated in some other way with the fact that they are men. The sole exception is a man who reported that he has received comments suggesting that “[he] should perform certain sexual acts” (R34). It should be noted, however, that he maintained that the standard comments he gets are about him being “stupid and ignorant” and that he has not been targeted as a sexual object (R34). Women, in contrast, reported experiencing several different types of gendered harassment, including gendered language with gender attributes, sexualizing comments, sexual invitations, and rape threats. One woman MP described the gendered dimension of online abuse in the following terms:

Women and girls really get “online hated” in a different way that is horrible. You notice a big difference if I write a post on Facebook or Twitter compared to if exactly the same post would come from a male colleague. Then you can get completely different reactions (R29).

This woman mentioned the use of much harsher words as an example of the reactions she has received; she confirmed that she has experienced personal attacks and abuse related to the fact that she is a woman. Another woman MP who embraces the positive potential of social media and actively attempts to engage in dialogue with the public online remarked that the more available one is on social media, the more vulnerable one becomes, and that this is especially true for women.

For some the price is very high, definitely. Women are treated so much worse than men. Very soon discussions break down and you are called a “whore” or a “bitch,” unacceptable things. And you wonder whether they would tell you those things to your face (R10).

Another woman has had several experiences of sexualized comments and unwanted sexual invitations, which on occasion turned into stalking and harassment in the strict sense:

I have a few hang-arounds, mostly older men, who write very positive comments, and I have found that nice, kind of a counterweight to all the online hatred. But it turned out that these men often have other intentions [months or years later]. They start making comments about my looks, and that they are sexually interested, and that’s difficult for me to handle (R49).

She explained how she has received private messages in the middle of the night on several occasions and that the comments turned into proper threats after she dismissed them. Other women shared similar stories. Further examples of the sexualized abuse that women experience included being sent “dick pics” (R41) and being the target of harassment that revolves around “you have too little sex and/or dick” (R44). One woman was accused of having obtained her position in parliament because she slept around (R43). Some of the gendered and sexualized comments contained serious threats of violence, such as “you should be raped” (R3). One woman was stalked for several years by a “hater” who was later convicted in court for his behavior (R14). This same MP has also received threats about being “raped and cut up,” especially when she engages in discussions on Twitter concerning sexualized violence against women.

These examples of harassment that target women are gendered in two ways. First, they are almost exclusively directed against women, not men; second, female gender is part of the content in one way or another. This type of abuse often includes several types of comments and gender manifestations at the same time, such as when a “nice” comment about an MP’s appearance turns into rape threats. A male MP’s description of the “typical abuse” that men face provides a contrasting example to the gendered abuse to which women are often exposed:

There was a long conversation in which someone said that “NN is a disaster because he’s so ignorant, he’s uninitiated.” Then another continued, “I think it’s because he’s illiterate, he can’t absorb information.” After that a third one stated that “it’s probably because he’s basically bribed” (R15).

Such comments are unpleasant and degrading, but they are nonetheless less personal in character, and thus less insulting, than the gendered abuse women experience.

It is significant that our interview data also indicated that ethnic background and sexual orientation generate a great deal of online abuse. A male MP who is openly gay explained that he regularly experiences harassment on social media:

90% of the cases have to do with my ethnic background and the rest with my sexuality. When I’m occasionally called an idiot, I hardly care (NN).

A number of other MPs with non-Swedish ethnic backgrounds have also had similar experiences, such as being called a “self-hating house nigger” (R26) and “baboon” (R4) or being told “you should be sent to Saudi Arabia” (R13).

Overall, a simple comparison of mean values reveals no significant gender gaps regarding the frequency of direct threats and offensive comments that men and women experience. We should note, however, that women are slightly overrepresented among those legislators who have experienced these two types of abuse often or very often, although they are also overrepresented among those who have never experienced direct threats. Women are also much more exposed to comments connected with gender/sexuality, both when we compare mean values and when we look specifically at the group of MPs who are most exposed to these types of comments. This survey finding is supported by the interviews, which indicate that men and women tend to be exposed to different types of abusive comments and that abuse targeting women is often gendered in its content. Women experience degrading comments/harassment that explicitly targets them as women and sexualizes them in various ways. Men, in contrast, do not appear to be targeted as men or exposed to sexualized comments as long as they appear to be heterosexual. Our findings also suggest that ethnic minorities and those with sexual-minority orientations receive a great deal of online abuse that is similar in kind to gendered abuse in that it targets an MP’s social background.

Gendered Consequences of Online Abuse

As a final step, we investigate the potential consequences that attacks on social media have on the targets of this type of violence. On the basis of the survey data, we first explore the association between online abuse and whether an MP has considered the possibility of resigning from parliament. Second, we examine other personal and potential political consequences of online abuse that surfaced in the interviews.

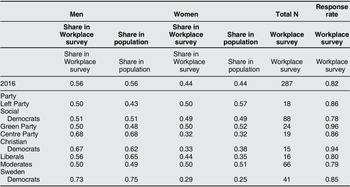

Interestingly, men who are targeted with online abuse in the form of offensive comments and direct threats are also slightly more inclined to have considered resigning from parliament (table 2).Footnote 12 For men, going from never having experienced offensive comments online (0) to experiencing offensive comments very often (10) is associated with an increase of 1.9 on the 0-10 scale for having considered resigning. In contrast, no statistically significant relationship between having considered resigning and being targeted with any of the three forms of abuse we have investigated is found for women. It is important to note in this regard that we can estimate only correlations, not the causal effects of different forms of online abuse on having considered resigning. In addition, the regression coefficients are rather small in all models, even when they reach statistical significance.Footnote 13

Table 2 Separate Models for Men and Women for Considering Resigning from ParliamentFootnote 14

Notes: Separate models for men and women respondents. Dependent variable: Have you ever considered resigning from your position in Parliament? Scale from 0, I have never considered resigning, to 10, I consider resigning very often. Main independent variable: How often have you experienced a) offensive comments, b) direct threats, c) comments linked to gender and/or sexuality on social media? Scale from 0 – never, to 10 – very often. Control variables: FE reports fixed effects. Frontbencher reports the difference between MPs with and without a frontbench position in Parliament. Young reports the difference between MPs who are 35 years of age or younger and those older than 35. Newcomer measures the difference between MPs serving their first term in Parliament and those who have served longer. Standard errors in parentheses: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

This counterintuitive finding suggests that online abuse can dampen the political ambitions of men more than those of women. It once again speaks to the benefit of studying all three dimensions—frequency, character, and consequence—in a coordinated fashion to assess in what way online abuse is gendered. Even though women are more targeted with a specific form of gendered abuse, we cannot simply assume that this would also translate into women being more likely than men to resign due to that exposure. Within the context of the present study, we can only speculate why men exposed to abuse appear to be more likely to leave parliament. For instance, men may react more negatively to online abuse because they do not expect it to be part of their daily life as a politician, whereas women may be more accustomed to abuse—both personally and from seeing other women subjected to it—and perhaps both expect and accept it as part of the politician’s job description (see also Pruysers, Thomas, and Blais Reference Pruysers, Thomas and Blais2020). Moreover, women who do make it into parliament may be more thick-skinned than men insofar as getting selected and elected may have been more difficult for them as women. Alternatively, being exposed to online abuse may be correlated with other nonobserved factors that predict whether an MP considers resigning. As such, exposure to online abuse may in and of itself mean little for MPs’ political ambitions.

Second, we use the interview data to further explore the personal and political consequences of online abuse. Many respondents remarked in the interviews that they feel constrained by the harsh and threatening tone they encounter on social media. MPs specifically mentioned that the strident atmosphere online has led politicians to be cautious about sharing details of their private lives. One respondent reflected on the changes that have taken place in the public debate in recent years:

Today we see a development on social media, politicians are often not private at all, on social media, for instance. They have opted out from that completely in order to avoid debate or critique—I think it’s a pity. I think we need to be more visible and show that we’re ordinary people (R28).

Perhaps more problematic is the fact that MPs also stated that they avoid certain topics that are perceived as generating a great deal of online abuse. As one respondent stated,

Those are the three, they trigger the trolls rather quickly—migration, integration, and gender equality (R22).

Although many respondents, both men and women, are aware of and problematize the risks associated with silenced voices and self-censorship on social media due to hatred and threats, many also claimed that they do not feel personally constrained and that they continue to address topics they find important. However, there is a clear gender difference within the group of interviewees who reported feeling personally constrained by online abuse in the sense that they are very cautious about what they post on social media, even avoiding certain topics. Women comprise a very large majority of the respondents who view their freedom online as being restricted by online abuse, whereas men comprise a clear majority of those who maintain that they are personally not affected in this manner. One woman remarked how she avoids posting personal pictures of a certain type:

I avoid posting pictures of myself in which I could be perceived as provocative. I’m aware when selecting pictures that I have to be prepared for comments on how I look or dress (R8).

Another woman related that there are certain topics concerning policy issues that she avoids:

There are issues that really are important to me, such as the question of refugees. Sometimes I choose not to write too much about it to avoid the debate (R5).

This experience is shared by several women respondents who described how the harsh climate online makes it difficult to engage with certain topics, which include the following:

topics regarding sexual harassment, rape, and talking about men’s responsibility and norms…. If I write about that on Twitter, it’s bizarre, I should be raped and cut up. It’s anti-racism and sexism, you can’t write about that on Twitter (R14).

The negative consequences of online abuse were also discussed by another woman respondent:

I know several of my colleagues, especially women, they don’t write about migration/integration, they don’t write about gender equality.… Me, on the contrary, I try to at times, but I simply put an end to the discussion [if necessary]. But I haven’t stopped writing (R22).

The fact that women appear to be more cautious than men in what they post on social media can potentially have an effect on the frequency of online abuse experienced by men and women. Stated otherwise, greater levels of self-censorship among women may in part explain why we—contrary to our initial expectations—did not find a gender difference concerning the frequency with which MPs are exposed to direct threats and offensive comments.

In general, we find that men MPs (but not women MPs) who have been more exposed to direct threats and offensive comments on social media are also slightly more likely to have considered leaving parliament. In the interviews, however, women MPs perceived online abuse and the harsh tone on social media as limiting their room for maneuver to a greater extent than men did. Although men acknowledged the risk of self-censorship, they seldom felt that their personal freedom was limited online as a consequence of abusive comments. It should also be noted that gender equality issues are mentioned as a particularly “sensitive topic” that attracts online abuse (see also Biroli Reference Biroli2018). This is a serious problem that has gendered consequences not only for women but for everyone who seeks to mobilize in support of improved gender equality.

Conclusion

We have argued in this article that it is essential to conceptually unpack how online abuse is gendered and empirically evaluate its frequency, character, and consequences through a gendered lens. By comparing men and women MPs’ experiences of online abuse in Sweden in respect to these three dimensions, our findings highlight the complex and multifaceted ways in which online abuse is gendered.

First, in contrast to our expectations, there appear to be no gender differences regarding the frequency of abuse experienced by men and women MPs in Sweden. Men and women, in fact, appear to experience fairly equal amounts of direct threats and offensive comments online. This casts light on the context-dependent character of online abuse insofar as women may be more highly exposed to violence in contexts where, unlike in Sweden, they are newcomers to the political arena and comprise a minority in parliament. Second, in line with our expectations, men and women MPs experience different forms of online abuse. Whereas men are primarily targeted in their role as politicians, women are targeted as gendered beings to a much greater extent: they are subject to degrading comments that explicitly target them as women and sexualize them in various ways. Third, we find that online abuse appears to affect men and women in different ways. We expected the type and frequency of abuse to matter (Herrick and Franklin Reference Herrick and Franklin2019) and the consequences to be gendered, and we find partial support for this expectation, albeit in an unexpected way. Men MPs who experience more online abuse are slightly more likely to have considered resigning from parliament, whereas we found no such relationship for women victims of online abuse. One possible explanation for this gender difference could be that women politicians have already taken into account the “additional costs” associated with being a woman in politics (cf. Shames Reference Shames2017).

Online abuse clearly has negative consequences for women as well, but of a different kind: women MPs report to a greater extent than men that they self-censor and are more careful with what they post on social media. This may be related to the type of abuse that women experience, which is personal to a greater degree and focuses on their gender and sexuality. It should also be noted that women’s potentially higher rate of self-censorship may in part explain the unexpected lack of a gender gap in the frequency of abuse men and women experience—if women avoid posting content they know will generate abuse online, they are less likely to be targeted. These results point to the importance of exploring the causal relationship between exposure to different types of (gendered) abuse and its consequences, including how it relates to men’s and women’s expectations of online abuse and their levels of acceptance. Another important finding in need of further exploration is the fact that issues related to gender equality appear to trigger online abuse, which may have negative implications for women’s substantive representation in the long run.

Although this empirical study is limited in scope, its findings demonstrate how our conceptualization of online abuse can add new shades of meaning to the widely held claim that online abuse on social media is gendered to the detriment of women politicians. However, more empirical research is needed to increase our knowledge in this regard about the differences and similarities across contexts. Although it is methodologically fruitful to use a mix of qualitative and quantitative data, we would also encourage future research to design surveys that capture all three dimensions—frequency, character, and consequences—in a comprehensive way. On a theoretical level, we believe that such studies will facilitate further theoretical development concerning the connections between frequency, type of abuse, its consequences, and how the gendering of one dimension might affect another. For instance, certain types of abuse may have detrimental consequences for the individual, even if they are less frequently experienced.

A final important finding worth highlighting is the indication that other political minorities, such as sexual and ethnic minorities, are targeted by online abuse in specific and severe ways. This finding emphasizes the need for future research to advance an intersectional agenda for studying online abuse and how such abuse incurs additional costs for certain groups, negatively affecting their political ambition and engagement in the long term (Shames Reference Shames2017). We agree with Kuperberg (Reference Kuperberg2018) that such intersectional analysis should inform not only a study of the frequency of online abuse but also an analysis of the forms of attack that politicians endure. In a similar vein, the possibility that the consequences of abuse may vary not only by gender but also by intersectional identities should be addressed in future research.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank participants in the ECPR joint session 2019 on Violence against Political Actors for useful comments on a previous version. They are also very grateful for the feedback from anonymous reviewers and the editorial team.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Funding details

This project is partly financed by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare FORTE, grant number 2018-01027.

Appendix

Table A1 Level of social media activity among Swedish MPs

Notes: Data from PTU 2012, 2014, and 2016.

Table A2 Sample representation, legislative workplace survey data

Table A3 List of respondents (R)

Note: Left includes the Social Democratic Party, the Left Party, and the Green Party. Center/Right includes the Centre Party, the Liberals, the Moderates, the Christian Democrats, and the Sweden Democrats. In some quotes the number is replaced with NN to avoid indirect identification of an MP.