No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 December 2020

In studies of Elizabethan pronunciation the method used has been consideration of such things as poetic rhythm, the spellings of people who could be expected to spell more or less phonetically, and rime. Many of the results are, naturally, doubtful, and there are many disagreements and questions left open. So far, except for one brief reference to Campian by Viètor, no one appears to have considered the possibilities offered by the examination of contemporary song books, especially those of the lutenists. In this paper I have studied some of the debated points in the light of the evidence from the music.

1 Wilhelm Victor, A Shakespeare Phonology (London, 1906), p. 115.

2 ∗John Attey, The First Booke of Ayres of Foure Parts, 1622.

William Barley, A New Booke of Tabliture, 1596.

∗John Bartlett, A Booke of Ayres with a Triplicate of Musicke, 1606.

∗Thomas Campian, Two Bookes of Ayres, undated (prob. date 1617).

——- ——–, The Third and Fourth Booke of Ayres, undated (prob. date 1618).

∗Michael Cavendish, 14 Ayres in Tablitorie, 1598.

John Cooper (Coprario), Funeral Teares, 1606.

—— ——-, Songs of Mourning, 1613.

∗William Corkine, Ayres, 1610.

——— ———, The Second Booke of Ayres, 1612.

∗John Danyel, Songs for the Lute Viol and Voice, 1606. (He was brother of the poet Samuel Daniel, in spite of the difference in spelling.)

∗John Dowland, The First Booke of Songs or Ayres, 1597.

——- ——-, The Second Booke of Songs or Ayres, 1600.

——- ——-, The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Ayres, 1603.

——– ———, A Pilgrimes Solace, 1612.

Robert Dowland, A Musical Banquet, 1610.

∗Alfonso Ferrabosco, Ayres, 1609.

∗Thomas Ford, Musicke of Sundrie Kindes, 1607.

Thomas Greaves, Songes of Sundrie Kindes, 1604.

Tobias Hume, Musicall Humors, 1605.

——– ——–, Captain Humes Poetical Musicke, 1607.

∗Robert Jones, The First Booke of Songes and Ayres, 1600.

——– ——-, The Second Booke of Songes and Ayres, 1601.

——— ——–, Ultimum Vale, or Third Booke of Ayres, 1608.

——— ———, A Musical Dreame, or the Fourth Booke of Ayres, 1609.

——– ———-, The Muses Gardin for Delights, or the Fifth Booke of Ayres, 1610.

George Mason and John Earsden, The Ayres That Were Sung and Played at Brougham Castle, 1618.

John Maynard, The XII Wonders of the World, 1611.

∗Thomas, Morley, First Booke, 1600.

∗Francis Pilkington, The First Booke of Songs or Ayres, 1605.

Walter Porter, Madrigales and Ayres, 1632.

∗Philip Rosseter, A Booke of Ayres, 1601.

Those starred have been edited with music. Note that Barley (1596) is the earliest, John Dowland next, and Porter (1632) the last, and that the movement is practically over with Campian (1618).

3 H. T. Fink, ed., Fifty Mastersongs by Twenty Composers (Boston, n. d.), p. 178.

4 H. J. C. Grierson, ed., The Poems of John Donne (Oxford, 1912), p. 432.

5 Miles M. Kastendieck, England's Musical Poet Thomas Campian (New York, 1938), pp. 68 f. et passim: b J. Pulver, A Biographical Dictionary of Old English Music (London, 1927) for Barley; J. Danyel; J. Dowland; J. Cooper; T. Campian; A. Ferrabosco; R. Jones; T. Hume: c Dictionary of National Biography, ed. Leslie Stephens and others (New York, 1885–89), for Raleigh; S. Daniel; Earl of Pembroke; T. Campian; Ben Jonson; d F. Howes, William Byrd (New York, 1928), p. 148: e H. Davey, History of English Music (London, 1921), p. 79.

6 Grove, Dictionary of Music, “Plain Chant.”

7 E. Douglas, compiler, A Plain-Song Service Book for the Episcopal Church (Boston, 1912), p. 83. “

8 E. H. Fellowes, English Madrigal Composers (Oxford, 1921), p. 66.

9 See footnote 2.

10 S. Moore, Historical Outlines of Phonology and Morphology (Ann Arbor, 1925), p. 100.

11 O. Jespersen, A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles (Heidelberg, 1909), 9.03.

12 S. Moore, Historical Outlines, p. 36.

13 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 12.22.

14 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, Prosody, and Pronunciation (Heidelberg, 1902), p. 205.

15 Ibid., and Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.87.

16 R. Bridges, Milton's Prosody (Oxford, 1921), pp. 23 f., 19 f.

17 See Endymiôn, in v, i, ii, iii, 6, and other words to be examined later.

18 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 2.743.

19 M. M. Kastendieck, England's Musical Poet Thomas Campian, p. 163.

20 Ibid., p. 59.

21 Alexander Gill, Logonomia Anglica, 1621 (Strassburg, 1903), has numerous examples of words in this ending, all showing dissyllabic endings, and Alexander Ellis, Early English Pronunciation, with Especial Reference to Shakespeare and Chaucer (London, 1869–89), contains word lists invariably showing the dissyllabic pronunciation for writers of this period.

22 Shakespeare, Sonnets, ed. R. M. Alden (Boston, 1916): beautious, iv, 5; hidious, v, 6; gracious, vii, 1; etc.

23 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.83.

24 The New English Dictionary gives two monosyllabic spellings for the ending of this word, neither occurring in this period. The dictionary says that the -eous endings in the early examples were probably dissyllabic. Of the verse illustrations in this period one has a dissyllabic ending and three have monosyllabic endings.

25 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, Prosody, and Pronunciation, pp. 137–138.

26 Not given in N. E. D.

27 There are in the N. E. D. no monosyllabic spellings of the ending of this word. Of the verse illustrations from this period one has the ending dissyllabic, the other monosyllabic.

28 T. Campian, Works, ed. A. H. Bullen (London, 1889), p. 260, Observations in the Art of English Poesie.

29 The N. E. D. gives but one monosyllabic spelling of this word, it from the Scotch. The three verse illustrations from this period, however, all have the monosyllabic ending.

30 The N. E. D. gives one monosyllabic spelling for the ending of this word as -ose, but it does not occur in this period. There is but one verse illustration of the word. Though the ending is monosyllabic, there is no clue as to whether it was pronounced [] or [s],

31 The N. E. D. gives but one verse illustration for this period, one in which the ending is monosyllabic.

32 See footnote 25.

33 See footnote 27. Campian, Observations, p. 26. Also the N. E. D. gives two monosyllabic spellings for the ending of this word, but neither occurs in this period. Of verse illustrations two have dissyllabic and one a monosyllabic ending.

34 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.83.

35 In view of what was said in the section on -ion as to the tendency of the i to be pronounced in words like envious, it is interesting to observe that this word is set both times in these airs as if the -ious were a single syllable. Campian, Fourth Booke, xx, ii, 3; Dowland, Third Booke, xxi, 4. Both Campian and Dowland were poets as well as musicians.

36 O. Jespersen, Modem English Grammar, 9.86 and 9.84.

37 Ibid., 9.811.

38 Ibid., 2.723.

39 Ibid., 12.23.

40 Campian, the author of these words, sets them with orient as just two syllables, Fourth Booke, vii, ii, 2.

41 Both Jones and Danyel at different times trained the children for the drama in the Queen's Revels. J. Pulver, A Biographical Dictionary of Old English Music.

42 See footnote 5.

43 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., p. 118. Gill, Logonomia Anglica, has clothi-er, p. 170, twentith, p. 220, costli-est, p. 171, fortith, p. 182, soldi-ers, p. 212, thirtith, p. 217, and Ellis, Early English Pronunciation, etc. has thirtith, p. 906, and twentith, p. 907. It may be significant and certainly is interesting, that all of the shortened forms are numerals, and the dissyllabic forms other words, adjective or noun.

44 The N. E. D. has dalliance once in this period with a monosyllabic ending, and alliance likewise. It says that the sixteenth-century pronunciation of alliance was alliánce; but Shakespeare always accents it on the i. Neither of these words is in Lady Hoby's Diary, nor in the Times letter on Merbecke (LTLS, April 12, 1923). Hart, Orthographie, p. 16, gives “garden ”for guardian and “melons ”and “millions ”as homonyms. But that this does not necessarily mean that both were pronounced [anz], may be suggested by the pronunciation current today in Virginia of “water millions ”for “watermelons.”

45 See sections on -ion, -ious, -ient.

46 Hart rimes marshal:martial.

47 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.03 and 9.88.

48 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in Printing, etc., pp. 97 and 116. Gill, Logonomia Anglica, and Ellis, Early English Pronunciation, always give -ia, -ial, or -ian as two syllables.

49 Campian, Songes from Rosseter's Booke of Ayres, xxi, ii, 1.

50 Shakespeare Phonology, p. 115.

51 G. Puttenham, The Art of English Poesie; Campian, Observations; S. Daniel, A Defense of Rhyme; G. Gascoyne, Certayne Notes of Instruction; G. Harvey, Foure Letters; and others included in G. Gregory Smith, ed., Elizabethan Critical Essays, and J. E. Spingarn, Critical Essays of the Seventeenth Century.

52 Gill, Logonomia Anglica gives tempesteous for tempestuous, p. 216, but tumultuous p. 220, virtuous, p. 222, and there are no examples in Ellis, Early English Pronunciation, except those already cited from Gill. It seems probable that the u in -uous was pronounced, but the sound is less certain. To be set as a monosyllable, it must have been a glide or consonantal. There are no examples of -ual in Gill or Ellis.

53 For musical illustration see section on -eth.

54 Gill, Logonomia Anglica, and other lists show these words as dissyllabic.

55 Gill, Logonomia Anglica, gives be-ing only.

56 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.812, gives [big] as its shortened form.

57 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., p. 90, No. 27.

58 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 5.73.

59 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.93.

60 Ante, words in -ia unaccented.

61 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.213.

62 Gill, Logonomia Anglica, gives fier as two syllables, p. 180, also fire as one, p. 180. Ellis gives two dissyllabic examples in Early English Pronunciation.

63 Note the realism in the rise of a tone with each repetition. This trait was characteristic of the lutenists wherever the words gave an opportunity. See also Dowland, Fourth Booke, xix, “Then sink, sink, sink, sink, Despair”; Pilkington's First Booke, xiii, “Climb, O heart, climb to thy rest”; Dowland, Third Booke, ii, “Cupid doth hover up and down, ”and Second Booke, iii, “But down, down, down, I fall down and arise”; Bartlett, Ayres, xix–xxi, “The blackbird whistled”; Danyel, ix–xi, “Drop, drop, drop, ”and many others.

64 Although the music is different, the refrain shows the same one tone rise at each repetition and the same note-values as in the previous example.

65 Campian, Second Booke, xii, ii, 7, and Fourth Booke, xi, ii, 1.

66 H. C. Wyld, Modern Colloquial English (London, 1920), p. 137.

67 Gill, Logonomia Anglica, gives these words as both one and two syllables; as does Ellis, Early English Pronunciation. In Gill, p. 147, ouer has two syllables in the verse and only one in the music, casting doubt on Gill's pronunciation.

68 Campian, Songes from Rosseter's Booke of Ayres, vi, i, 7.

69 Cf. Elizabethan spelling hower.

70 Ellis, Early English Pronunciation, p. 900, gives prayer as two syllables.

71 The Shakespeare Concordance gives fire, bower, hour, prayer, as two syllables: T. A., iii, i, 75; T. A., i, i, 127; Rich., ii, i, iii, 294; T. A., ii, iii, 256, vi, iv, 54; M. W., iv, v, 54. The examples in N. E. D. from verse quote :fire, bower, shower, tower, as monosyllables, and flower and shower more often as one. It gives hour once as dissyllabic, flower twice, Prayer is dissyllabic twice and monosyllabic twice. Briar is more often dissyllabic than monosyllabic. Lady Hoby spells hower and flower. But she spells prayer in four different ways: pair, prater, praer, and prers. I wonder whether the -er in two of these forms had any syllabic value, for she spells maid, maied (p. 98). I do not suppose that she said mai-ed. Hart gives mower-more; lower-lowre-lour; lore-lower; power-powre-pour. In Merbecke oure is one syllable, but prayer always two.

72 W. Viètor, A Shakespeare Phonology, pp. 110 and 113. Also O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 2.325.

73 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., p. 106, No. 97.

74 Ibid., pp. 89, 90.

75 The N. E. D. gives no spelling of brother which would indicate that it ever was pronounced as a monosyllable. As to either, none of the examples has fewer than two syllables, and there is no example of er later than 1389. The word either occurs in Shakespeare in a first foot, as taking the place of one syllable (Measure for Measure, ii, ii, 96, iii, i, 5). Whether, when so spelled in Shakespeare, is always dissyllabic, and there are illustrations of wher and where as monosyllabic forms.

76 Cf. Midsummer Night's Dream, i, i, 105 “Why shoúld not I then prósecùte my ríght? ”and i, i, 15, “The pále compánion ís not for our pómp. ”But there nothing to hinder the reader from speaking these negatives in full, and that they really were contracted to n't is not demonstrable.

77 Cf. ‘scape, ‘mongsl, ‘lection, B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., p. 88, No. 2, and ‘seech for beseech, p. 85, No. 10.

78 Ibid., p. 88, No. 20.

79 Ibid., p. 88, No. 22.

80 Ibid., 88, No. 23.

81 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.94.

82 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.92.

83 Ante, footnote 50.

84 See Corkine, Second Booke, ix, ii, 4; Dowland, Second Booke, xiv, i, 2; Jones, Fifth Booke, xiv, v, 6. See also supra my own discussion of means to produce accent.

85 Gill, Logonomia Anglica, gives spirit twice, but no shortened forms.

86 The list includes: maiden, leaden, hidden, forbidden, chidden, trodden, loden, sudden, golden, harden, garden, burden; fallen, swoll'n, stolen, sullen; shaken, taken, ta'en, quicken, liken, silken, broke, broken, oaken, spoken, betoken, hearken, darken; open, ripen; barren; lessen; listen, hasten, oft, often; cosen, chosen, frozen; sweeten, threaten, heighten, beaten, written, gotten, forgotten, shorten; heaven, heavenly, heavenlier, even, ev'n, evening, e'en, haven, raven, driven, given.

87 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., 92, No. 34.

88 Corkine, Second Booke, viii, iv, 4.

89 Jones, Fifth Booke, xiv, vi, 6.

90 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., p. 69.

91 Ante, discussion of spirit.

92 Campian, Fourth Booke, xi, iii, 1, and Jones, Fifth Booke, iv, iii, 3.

93 The Shakespeare Concordance has barren but once (Titus Andronicus, ii, iii, 93). Lady Hoby does not give it. In the N. E. D. there are no spellings to indicate any such pronunciation as barr'n. There are three illustrations of barren, one in prose. Of those in verse, one is clearly dissyllabic, the other, on the theory of strict syllable count, apparently monosyllabic. Hart on p. 16 gives baron - barren. Wright's Dialect Dictionary gives spellings for warrant in different dialects that indicate monosyllabic pronunciations, but none for barren, which is spelled baron, barran, and barron, and marked with the pronunciation [].

94 Bartlet, A Booke of Ayres, viii, iv, 2, and vi, i, 5.

95 Dowland, Fourth Booke, viii, ii, 5, and many others.

96 Jones, Third Booke, xix, i, 2, oft, ii, 1, often.

97 Pilkington, First Booke, xxi, i, 8.

98 Ferrabosco, Ayres, vi, 17, and elsewhere.

99 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 7.735.

100 Ibid., 6.19.

101 S. Moore, Historical Outlines, p. 125.

102 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.811.

103 Ibid.

104 Ibid., 9.92.

105 S. Moore, Historical Outlines, pp. 104 ff.

106 Ibid., p. 138.

107 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.92.

108 Gill, Logonomia Anglica, has regularly the full pronunciation of -est, with no discrimination between verbs and adjectives: costliest, p. 171; kindest, p. 192; rentierest, p. 206; stricktest, p. 214; and there are no examples in Ellis except those from Gill.

109 Moore, Historical Outlines, p. 131.

110 Ibid., p. 130.

111 Hart and Hodges both give all such words as riming with words enging in -s: freeze -freeth; fleas - fleaeth - flayeth; flours - floureth; jests - gests - jesteth; boughs - boweth; furs - furreth. But Hart, p. 11, spells out en - du - eth and on p. 8 giv - eth, where he is marking syllabication. On p. 8 he has also taktk. There is evidently some distinction between the two pronunciations. The note on Merbecke in the Times Literary Supplement, April 12, 1923, says that -eth is always a separate syllable even when preceded by a vowel. Bloweth is not in the Shakespeare Concordance. Of groweth there is one example (Taming of the Shrew, iii, i, 63), where it is dissyllabic. There is np illustration of grows. All the words in -eth that I have checked give it syllabic value. In the case of oweth there is an illustration giving oweth and owes in the same quotation (Taming of the Shrew, v, ii, 156) : “Such duty as the subject owes the prince, Even such a woman oweth to her husband. ”From these examples it is obvious that -eth was not always equivalent to -s in this period.

112 S. Moore, Historical Outlines, p. 111, par. 94.

113 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 6.19.

114 The N. E. D. gives “sithe ”sb2 1609, Armin, Maids of More Clacke, E iv, and Cowley, Pyramus and Thisbe, 71, and from modern dialects of Northamptonshire and Gloucestershire.

115 There are no examples in Gill, Logonomia Anglica, or in Ellis, Early English Pronunciation, of contracted -eth, even with a vowel preceding, except in words like twentilh, thirtilh, and fortith, which are regularly shortened.

116 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.02.

117 W. Viètor, A Shakespeare Phonology, pp. 109 f.

118 S. Moore, Historical Outlines, pp. 88 ff.

119 Ante, section on -en.

120 Fourth Booke, vii, iii, 2.

121 Third Booke, x, iii, 3

122 See also lightening, Campian, Second Booke, xix, ii, 2, and Dowland, Second Booke' xi, ii, 4; and lightning, so spelled, ibid., xxi, ii, 6; hardening, Jones, Fifth Booke, vi, ii, 2°

123 Campian, First Booke, iii, i, 2; Corkine, First Booke, xi, iii, 2, and iii, ii, 1; Dowland' Second Booke, ix, i, 2; Ford, Musicke of Sundrie Kindes, ii, i, 3; Jones, Fifth Booke, xix, ii, 1.

124 Campian, Third Booke, iv, iii, 2; Cavendish, Ayres, xii, i, 1; Dowland, Second Booke, xiii, i, 1; Pilkington, First Booke, vi, ii, 3.

125 Bartlet, A Booke of Ayres, viii, ii, 2 : he has in ii, ii, 5 also watery; Jones, Second Booke, xi, i, 5.

126 Dowland, First Booke, xii, iii, 6.

127 Ferrabosco, Ayres, vii, ii, 4.

128 The N. E. D. gives the following evidence for words in this group:

| favorite | —3 verse illustrations—3 syllables |

| ivory | —3 verse illustrations—3 syllables |

| ivory | —3 verse illustrations—2 syllables |

| misery | —2 verse illustrations—3 syllables |

It also says that in the fifteenth century there was a word mis're from OF misère and also that misery was sixteenth century colloquial for misère at cards

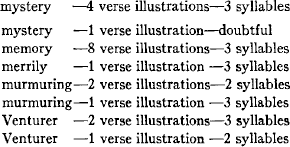

| mystery | —4 verse illustrations—3 syllables |

| mystery | —1 verse illustration—doubtful |

| memory | —8 verse illustrations—3 syllables |

| merrily | —1 verse illustration—3 syllables |

| murmuring | —2 verse illustrations—2 syllables |

| murmuring | —1 verse illustration—3 syllables |

| Venturer | —2 verse illustrations—3 syllables |

| Venturer | —1 verse illustration—2 syllables |

In these words it is evident that the light vowel was more often pronounced than omitted. The only examples of this kind of word in Lady Hoby's Diary were ignorant, p. 66, medesons (always so spelled), misirie, p. 73, all of the spellings indicating the pronunciation of the light vowel. On the other hand Hart gives poplar - popular, p. 18, and happily - haply, p. 15. The note on Merbecke (LTLS, April 12, 1923) says he always spells Heartily, hertly, but the two were different words altogether.

129 Danyel, Songes for the Lute, ii, 7.

130 Ante, discussion of spirit.

131 Dowland, Third Booke, iv, i, 6; Pilkington, First Booke, xiv, iii, 2.

132 Cavendish, Ayres, vi, v, 2.

133 Danyel, Songes for the Lute, xvii, ii, 4.

134 Campian, Second Booke, xxi, ii, 3.

135 Corkine, Second Booke, xiii, 5.

136 Second Booke, xix, iii, 2.

137 Campian, Third Booke, xviii, ii, 1.

138 Jones, First Booke, xv, i, 3.

139 Jones, Third Booke, v, iii, 7.

140 Jones, Fourth Booke, xv, ii, 1, and Pilkington, First Booke, xix, i, 3.

141 Gill, Logonomia Anglica, 1621, gives adultery, 3; chansler, 169; dishonourable 175; enlightened, 176; every 178; evning, 178; funeral, 183; generous, general, 183; lightning, 193; literature, 194; miserable, 197; misery, 197; pickrel, 203; prizner, 204; reckning, 206; renderest, 206; strengtheneth, 210; suffrance, 214; sustenans, 213; temperance, 215; thundring, 218; tottering, 219; wandred, 223; Ellis,Early English Pronunciation, gives attempred, p. 880; evn, p. 888. Both of these show considerable variation in the treatment of the unaccented vowel even when the following consonant is /r/.

142 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc. pp. 189f.

143 Chapters in English Printing, etc., pp. 68 f.

144 S. Moore, Historical Outlines, p. 111, No. 94.

145 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 9.85.

146 Ibid.

147 Dowland, Fourth Booke, xvi, 2.

148 Corkine, Second Booke, xiv, ii, 6.

149 Danyel, Songes for the Lute, xii, 6.

150 Dowland, First Booke, xii, iii, 6.

151 Pilkington, First Booke, xix, i, 3.

152 Rosseter, Songes from Rosseier's Booke of Ayres, xviii, i, 4.

153 See Ebenezer Prout, ed. The Messiah, A Sacred Oratorio, by G. F. Handel, 1741 (London, 1902).

154 M. A. Bayfield, A Study of Shakespeare's Versification (Cambridge, 1920), p. 300.

155 B. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., p. 77.

156 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 6.13.

157 W. Viètor, A Shakespeare Phonology, p. 110.

158 S. Moore, Historical Outlines, p. 111, par. 94.

159 G. Puttenham, The Art of English Poesie (Westminster, 1895), p. 174.

160 R. Bridges, Milton's Prosody (Oxford, 1921), p. 10.

161 F. B. Gummere, A Handbook of Poetics (Boston, 1913), pp. 189 f.

162 H. C. Wyld, History of Colloquial English, p. 146.

163 W Viètor, A Shakespeare Phonology, p. 115.

164 O. Jespersen, Modern English Grammar, 6.13.

165 O. Jespersen, Modem English Grammar, 9.82.

166 M. A. Bayfield, Shakespeare's Versification, p. 300.

167 E. Van Dam and C. Stoffel, Chapters in English Printing, etc., pp. 89–94.