Introduction

Arctic communities face multiple cross-scale changes in socio-economic, political, environmental and cultural systems that have cascading impacts on local community viability. Throughout the past decades, Arctic scholars have been examining local responses and the local capacity to adapt to climatic and non-climatic changes occurring within and outside the Arctic region. At the same time, certain emerging changes, such as shipping development, have received less attention. In addition to the lack of knowledge on shipping impacts in Arctic communities, the Russian local communities and the Russian context are still understudied by Arctic scholars (Ford, McDowell, & Pearce, Reference Ford, McDowell and Pearce2015) and less is known about their capacity to adapt to climate-induced changes. This disparity exists despite the fact that Russia represents nearly half the Arctic geographically and almost 40% of the Arctic demographically (Shestak, Shcheka, & Klochkov, Reference Shestak, Shcheka and Klochkov2019). Hence, in order to examine how the adaptive capacity of Arctic communities is understood in the Western and Russian literature, this study aims to (1) examine the status of adaptive capacity knowledge pertaining to local Arctic communities in the context of ongoing and emerging climatic and non-climatic change; (2) understand what conditions enable community adaptation and (3) examine whether and how the shipping development is addressed in those studies.

The existing scientific literature recognises that the historical adaptability and flexibility of Arctic community livelihoods is strained by the complexity and pace of climatic (Meier et al., Reference Meier, Hovelsrud, van Oort, Key, Kovacs, Michel and Reist2014, p. 205) and non-climatic changes (see, for example, AMAP, 2017; Hovelsrud & Smit, Reference Hovelsrud and Smit2010; Rasmussen, Hovelsrud, & Gearheard, Reference Rasmussen, Hovelsrud and Gearheard2014). According to a recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pörtner, Roberts, Skea, Shukla and Waterfield2018), the Arctic region is warming 2–3 times faster than the rest of the globe (AMAP, 2017b; Overland et al., Reference Overland, Dunlea, Box, Corell, Forsius, Kattsov and Wang2018). Sea ice reduction is arguably one of the most noticeable changes in the Arctic (Meier et al., Reference Meier, Hovelsrud, van Oort, Key, Kovacs, Michel and Reist2014) since it retreats and migrates norward with warming global temperatures. The number of days with sea ice cover has been declining by ten–twenty days per decade during the period 1979–2013 (AMAP, 2017b, p. viii).

Discussion on adaptive capacity in the literature on global environmental change has burgeoned around the topic of climatic evaluation (Engle, Reference Engle2011). This literature, among others, examines the necessity to develop adaptation measures to new climatic realities in the context of economic development (Lopulenko, Reference Lopulenko2009). In studies that apply an adaptation framework, adaptive capacity is embedded in the vulnerability paradigm; however, adaptive capacity is also connected to resilience research, where adaptability is described as “the capacity of actors in a system to influence resilience” (Walker, Holling, Carpenter, & Kinzig, Reference Walker, Holling, Carpenter and Kinzig2004). Adaptive capacity in vulnerability research follows an actor-centred approach (Engle, Reference Engle2011). It usually refers to the conditions and abilities that enable people to adjust to changing conditions (e.g. Hovelsrud & Smit, Reference Hovelsrud and Smit2010; Smit & Wandel, Reference Smit and Wandel2006) by minimising the consequences and/or take advantage of new opportunities (Cinner et al., Reference Cinner, Adger, Allison, Barnes, Brown, Cohen and Morrison2018). Adaptive capacity is argued to be latent in its nature and needs to be activated to enable adaptation (Bay-Larsen & Hovelsrud, Reference Bay-Larsen, Hovelsrud, Fondahl and Wilson2017; Brown & Westaway, Reference Brown and Westaway2011). However, despite a clear conceptualisation of adaptive capacity, there is still a debate on the contextual conditions that enhance and/or activate adaptive capacity. Hence, the understanding of the adaptive capacity framework as developed by Arctic scholars and its salient elements in responding to changing conditions represents the primary research interest of this study.

Arctic shipping represents one example of a changing condition to which local communities may respond to in varying ways (AMAP, 2017; Christensen, Lasserre, Dawson, Guy, & Pelletier, Reference Christensen, Lasserre, Dawson, Guy and Pelletier2018). Arctic shipping refers here to all types of vessels operating in the Arctic (AMSA, 2009), destination, transition and local. The vessel types vary from small pleasure crafts to large overseas cruises, as well as fishing, research, cargo and government vessels (Dawson, Copland, et al., Reference Dawson, Copland, Johnston, Pizzolato, Howell, Pelot and Parsons2017). Though some of the vessels have an ice class, meaning they are enabled for year-around operation in ice-covered waters (IMO, 2010), much of the traffic takes place in open waters and summer navigation.

Growing trends in Arctic shipping for the past two decades are often connected to climatic and socio-economic changes. Declining sea ice opens new areas in the Arctic Ocean and results in the extension of the navigation season and increases the possibility for transiting along the Northeast and/or Northwest Passage. Additionally, fisheries and extractive industries are moving northward, and the area is becoming more attractive to marine tourism (e.g. Dawson, Pizzolato, Howell, Copland, & Johnston, Reference Dawson, Pizzolato, Howell, Copland and Johnston2018).

Even though shipping activities have grown and will continue to increase in several Arctic regions, knowledge of how shipping growth affects local communities is rather fragmented. Sea ice decline presents opportunities for shipping development, yet we know little about these opportunities and how they should be managed (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012, p. 296). A recent literature review on Arctic shipping underlined the deficit of studies that address social and environmental impacts from this growing sector (Ng, Andrews, Babb, Lin, & Becker, Reference Ng, Andrews, Babb, Lin and Becker2018). Existing studies that address the social and environmental impacts of Arctic shipping have mostly covered the Canadian Arctic (e.g. Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Lasserre, Dawson, Guy and Pelletier2018; Dawson, Johnston, & Stewart, Reference Dawson, Johnston and Stewart2017), while socio-economic and governance aspects of marine cruise development have also been explored for several other Arctic regions (e.g. Grushenko, Reference Grushenko2014; Olsen, Nenasheva, et al., Reference Olsen, Nenasheva, Wigger, Pashkevich, Bickford, Maksimova, Pongrácz, Pavlov and Hänninen2020; Pashkevich, Dawson, & Stewart, Reference Pashkevich, Dawson and Stewart2015; Stewart, Dawson, & Johnston, Reference Stewart, Dawson and Johnston2015; Van Bets, Lamers, & van Tatenhove, Reference Van Bets, Lamers and van Tatenhove2017).

This study aims to contribute to an increasing body of literature on community-based adaptation (Schipper, Ayers, Reid, Huq, & Rahman, Reference Schipper, Ayers, Reid, Huq and Rahman2014) that also corresponds with socially oriented observation transdisciplinary approach on sustainable knowledge coproduction (Vlasova & Volkov, Reference Vlasova and Volkov2016, pp. 429–430). Hence, this study (1) provides insight on the status of research on Arctic community’s adaptive capacity and (2) expands knowledge on whether and how the Arctic shipping development is understood as a changing condition that local communities respond and/or adapt to. In doing so, this article began with a presentation of the significance of the topic, which will be followed by a detailed explanation of its methods – e.g. a description of the systematic literature review. The Results section conceptualises local adaptive capacity based on contributions from Arctic Western scholars, discusses the ways this framework is addressed among Russian scholars, identifies elements that constrain local adaptive capacity and examines whether and how shipping is addressed in the literature on adaptive capacity. In the Discussion section, I synthesise the results of the literature review to illustrate the development of the adaptive capacity framework.

Methods

The study adopts a systematic literature review of peer-reviewed journal articles in order to examine the status of knowledge – developed by the Western and Russian scholars – regarding local adaptive capacity in the Arctic, and whether, and how, shipping development is addressed in those studies. The systematic review process was developed based on the guidelines for conducting literature reviews (e.g. Biesbroek et al., Reference Biesbroek, Berrang-Ford, Ford, Tanabe, Austin and Lesnikowski2018; Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, & Jackson, Reference Easterby-Smith, Thorpe and Jackson2012; Ford et al., Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012). According to Ford et al. (Reference Ford, Berrang-Ford and Paterson2011, p. 328), the systematic literature review presents an assessment of the state of knowledge on a specific topic. Such reviews consist of three main components: data collection (clearly formulated questions and syntaxes), full reporting on criteria for inclusion and exclusion of articles and the possibility of using quantitative and qualitative analysis (ibid).

During the data collection process, the question for literature review was defined as follows: What characterises the local adaptive capacity of Arctic communities? To respond to this question, the following sections discuss literature on adaptive capacity from all Arctic nations, including Russia. The inclusion of which adds novelty to this study. The ability to combine results published in both English and Russian provides a more robust and comprehensive overview of published Arctic research.

In order to incorporate peer-reviewed scientific articles from several Arctic regions, two main electronic databases were chosen as follows: Scopus in English and eLIBRARY.ru in Russian (that was supplemented with Google Scholar) to search for Russian language articles. Though the search and selection options of the selected databases are similar, it is important to note that Scopus includes studies on the Russian Arctic only if they are published in English, whereas eLIBRARY.ru is a useful database to search for studies that are published in Russian. However, due to a small number of relevant articles and accessibility issues with some of the selected articles in eLIBRARY.ru, a secondary Boolean search and a search for specific Russian language articles were run in Google Scholar.

The following Boolean search – a keyword-searching syntax – was applied in Scopus: ((adapt* AND capacity AND commun* OR local) AND arctic OR “high north” OR northern AND Alaska OR Canada OR Russia OR Norway OR Sweden OR Finland OR Iceland OR Greenland) AND (EXCLUDE (PUBYEAR, 2019) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)). The search protocol in eLIBRARY.ru was similar; however, three main adjustments were necessary. First, since the search in the Russian database aimed to assess only Russian literature about adaptive capacity in the Russian Arctic, and other Arctic countries were excluded. The second adjustment was necessary due to differences in translation and the concepts used in the Russian language. To be more specific, the translation of the core concepts like “adaptive capacity” and “local communities”. The word “capacity” can be translated in various ways, such as “sposobnost” (ability or capacity), “potencial” (potential) and “vozmozhnost” (ability). Hence, in the search syntaxes, I chose to use only “adapt*” instead of “adapt* AND capacity”. The use of another relevant concept, local community (in Russian “mestnye soobshchestva”), retrieves the results from natural sciences that describe communities of flora and fauna. Hence, I found it valuable to add a concept of populace (in Russian “naselenie” or “narody”).

Finally, the Arctic as a geographical region in Russian studies is usually associated with the high Arctic, mostly the territory above the Arctic circle (The President of the Russian Federation, 2014). The Russian geographical border of the Arctic differs from and is smaller (especially in the eastern part) compared to the one defined by the Arctic Human Development Report (AHDR, 2004) and broadly used by the Western scholars. A precise definition of the Russian Arctic area (that is defined by the Russian government) was presented in the Arctic Council’s agreement (2017) on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation. Moreover, the published studies by the Russian authors do not necessarily include the term Arctic to describe the geographical area of their research. The most common words to describe the region is “high north” and/or just “north”, e.g. Russian north and northwest Russia (see, for example, Lazhentsev, Reference Lazhentsev2016).

In order to address those challenges in addition to narrowing the search focus, I applied an adjusted syntaxis and had to run several search tests with a combination of different translation opportunities. These adjustments were necessary; however, they led to a large number of search results that were not necessarily relevant as most were focused on natural science research or human health-related research. Additionally, as mentioned, not all results of interest in this study were accessible via eLIBRARY.ru, thus, a supplementary search in Google Scholar was used.

Those exclusion and inclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. The systematic literature review includes scientific articles published between 2000 and 2018. This period was chosen to reflect the IPCC’s Third Assessment Report, Working Group II, which highlighted adaptive capacity within studies on global environmental change (IPCC, Reference McCarthy, Canziani, Leary, Dokken and White2001).

Table 1. Criteria for literature inclusion and exclusion (modified from Ford et al., Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012).

The Boolean search, which involves a search for both keywords and abstracts (Biesbroek et al., Reference Biesbroek, Berrang-Ford, Ford, Tanabe, Austin and Lesnikowski2018), was conducted in 2019. The search resulted in 118 relevant articles on Scopus and 39 in eLIBRARY.ru. An abstract screening was conducted to examine whether articles addressed adaptive capacity and/or comparable concepts within adaption studies. This process limited the total number of articles to 54 in Scopus. To evaluate the relevance of the Russian articles, during the screening process, I also had to include articles’ introductions, as some abstracts were of limited length or absent, making it difficult to assess the theoretical choices. In total, 12 articles in eLIBRARY.ru and Google Scholars were selected that are connected to local context and adaptability to climate-induced changes in the Arctic. Those selected Russian articles present the conceptual application of the adaptation framework and the differences from Western studies, rather than an assessment of adaptive capacity.

I coded these selected articles in qualitative data analysis software, NVivo, using predefined coding categories, such as the conceptualisation of adaptive capacity, connection to other social attributes within the adaptation framework (e.g. vulnerability, resilience and adaptive responses), adaptive capacity aspects and/or dimensions and limitations. Some emerging categories (e.g. the type of change, region and study methods) were added during the analysis process. The results of literature review are presented in the Results section.

Results

This section presents the results from the systematic literature review. It begins with the conceptualisation of adaptive capacity by Western scholars and follows with a presentation of how Russian scholars have interpreted and used this framework. It also examines aspects of adaptive capacity as well as shipping development and its treatment in selected studies.

Adaptive capacity in Western studies

Within the literature on global environmental change, the concept of adaptive capacity (earlier described as “adaptability”) has its origin in the vulnerability approach highlighted in the Third AR IPCC report (Smit & Pilifosova, Reference Smit, Pilifosova, McCarthy, Canziani, Leary, Dokken and White2001 in Ford & Smit, Reference Ford and Smit2004). The reviewed studies that examine adaptive capacity employ vulnerability as a central concept. Vulnerability is defined as a susceptibility to changing conditions (Keskitalo & Kulyasova, Reference Keskitalo and Kulyasova2009) and is a function of both exposure sensitivity to impacts of a changing condition and the adaptive capacity to deal with those impacts (Ford & Smit, Reference Ford and Smit2004).

Exposure sensitivity relates to one’s susceptibility to impacts of changing conditions in a particular place over time (e.g. Risvoll & Hovelsrud, Reference Risvoll and Hovelsrud2016), while adaptive capacity refers to one’s (in this study community) ability to address, plan for, or adapt to these impacts (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Gough, Laidler, MacDonald, Irngaut and Qrunnut2009; Ford, Smit, & Wandel, Reference Ford, Smit and Wandel2006; Ford, Smit, Wandel, & MacDonald, Reference Ford, Smit, Wandel and MacDonald2006) and take advantage of new opportunities (Debortoli, Sayles, Clark, & Ford, Reference Debortoli, Sayles, Clark and Ford2018). This or a similar definition of adaptive capacity is commonly used in the reviewed literature.

The reviewed studies suggest that the relationship between adaptive capacity and exposure sensitivity is context dependent and varies over time and scale (Debortoli et al., Reference Debortoli, Sayles, Clark and Ford2018), while an increase in a communities’ adaptive capacity and/or resilience leads to a decrease in vulnerability (e.g. Kvalvik et al., Reference Kvalvik, Dalmannsdottir, Dannevig, Hovelsrud, Rønning and Uleberg2011). Hence, some scholars argue that in adaptation studies, adaptive capacity was described as a synonym to resilience (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Kasperson, Matsone, McCarthy, Corell, Christensene and Schiller2003 in Risvoll and Hovelsrud, Reference Risvoll and Hovelsrud2016). In adaptation research, resilience is described as another attribute of socio-ecological systems associated with coping mechanisms, where the term “adaptive” refers to the evolutionary/ecological description of responses that increase the probability of survival (Berkes and Jolly, Reference Berkes and Jolly2002).

Adaptive capacity, in the vulnerability approach, is socially constructed. Adaptive capacity is approached as a dynamic attribute that varies across communities (Ford, Smit, & Wandel, Reference Ford, Smit and Wandel2006; O’Brien, Eriksen, Sygna, & Naess, Reference O’Brien, Eriksen, Sygna and Naess2006). Assessments of adaptive capacity tend to place emphasis on the local level (e.g. Keskitalo, Reference Keskitalo2008; Risvoll & Hovelsrud, Reference Risvoll and Hovelsrud2016), as it is dependent on political and economic settings, scientific and traditional knowledge, as well as resource distribution, involved stakeholders (Adger, Brown, & Tompkins, Reference Adger, Brown and Tompkins2005 in Keskitalo and Kulyasova, Reference Keskitalo and Kulyasova2009) and communities’ ability to act collectively, also described as human agency (e.g. Hovelsrud et al. Reference Hovelsrud, Karlsson and Olsen2018). Additionally, it should be noted that due to uneven distribution of resources and power across scales, the enhancement of adaptive capacity for one group of stakeholders (those who gain access to the resources) may reduce the adaptive capacity of another (those who lose the access to resources) (Keskitalo & Kulyasova, Reference Keskitalo and Kulyasova2009).

In line with Debotoli et al. (2018), this review indicates that there is a long tradition of vulnerability and adaptation research in Canada. From a geographical perspective, Canadian–Arctic communities are represented most prominently in the captured studies, followed by Alaskan communities and communities in Scandinavian countries. Less knowledge has been accumulated on Russian communities. While the majority of these studies use single case study research designs, a few establish multiple cases within and outside the Arctic region. One of these comparatively analyses local adaptive capacity in Nordic countries and Russia, illustrating the contextual differences between those communities.

Russian studies

As the previous section illustrates, only a few studies published in English explore the Arctic Russian context as it pertains to adaptive capacity. Simultaneously, only a few Russian studies reflect on local communities and their abilities to adapt to changing conditions.

Here, it is also important to mention that the Western-developed vocabulary of adaptation studies is not always used in studies published by Russian scholars that describe the impacts of changes taking place in northern communities. Moreover, Riabova and Klyuchnikova (Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018, p.101) recognise that, despite an increasing attention among the Western Arctic scholars to the research on social impacts of climate-induced changes, fewer studies are dedicated to Russian communities also by Russian scholars.

A decade ago, Lopulenko (Reference Lopulenko2009, p. 142) argued that even though there is a certain understanding of climate change impacts, little research investigates these impacts’ role in the social aspects of Arctic life. During the past decade, the topic has received more attention, especially after adopting a Climate Doctrine of the Russian Federation in 2009 (Riabova & Klyuchnikova, Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018). However, most of the focus has been given to sectoral and adaptation to climatic changes or to adaptation of Russian regions (e.g. Murmansk oblast). Those units of analysis are not considered in this review – that is, local level communities. The literature search results indicate that in contrast to Arctic studies where an understanding of adaptive capacity among others derives from local levels such as communities, municipalities and local economic sectors (e.g. Ford, Couture, Bell, & Clark, Reference Ford, Couture, Bell and Clark2018; C. Keskitalo, H. Dannevig, G. Hovelsrud, J. J. West, & A. Swartling, Reference Keskitalo, Dannevig, Hovelsrud, West and Swartling2011), studies covering the Russian Arctic use either an individual or diverse sectoral and regional levels as units of analysis and fewer community-level cases.

However, it is important to mention that adaptation studies of the Russian Arctic population have a long history extending back to the 1930s, a period marked by intensive development in Arctic territories and by the opening of the Northern Sea Route (Maximov & Maximova, Reference Maximov and Maximova2007). The first generation of studies was dedicated to health and/or the physical human ability to survive in harsh climates, which later led to the establishment of a new scientific subdiscipline of ecological physiology in the 1990s (ibid.). This research area is still emerging and, similar to Western studies, the concept of adaptive capacity is mainstreamed in biophysical, physiological and psychological studies. Searching results indicate that adaptive capacity has been studied at the individual level and at the group level when studying health challenges.

The recent literature review on the social consequences of a changing climate in the Arctic (Riabova & Klyuchnikova, Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018, pp. 91–92) indicates that foreign literature (that is outside of Russia) is more advanced in addressing social impacts, while Russian studies are dominated by biological and ecological impact assessments. The same review states that research on climate impacts and adaptation in local and indigenous communities at local and regional levels is covered less frequently but is gaining prevalence among Russian scholars (ibid). Developing the adaptive capacity framework is also increasingly important, as it helps to identify the adaptation options and strategies of local communities (Nechiporenko, Reference Nechiporenko2015).

The existing studies also indicate that though Arctic residents are exposed to impacts of climatic and climate-induced changes (Boyakova, Vinokurova, Ignatjeva, & Filippova, Reference Boyakova, Vinokurova, Ignatjeva and Filippova2010; Filippova, Reference Filippova2011; Oparin, Kulikova, & Shchigreva, Reference Oparin, Kulikova and Shchigreva2011; Vinokurova, Filippova, Suleymanov, & Grigorev, Reference Vinokurova, Filippova, Suleymanov and Grigorev2016), several changes require adaptation measures. The literature describes the changes that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and a transition towards the market economy that, taken together, negatively affected the traditional livelihoods of several Arctic indigenous and local communities (Perevalova, Reference Perevalova2015). Other changes that are discussed in the reviewed literature are changes in ecosystem services (Leksin & Porfiryev, Reference Leksin and Porfiryev2017), industrial expansion to the north (Perevalova, Reference Perevalova2015) and, as a result, demographical changes of the Arctic population (Tomaska, Reference Tomaska2015). Less attention is given to direct impacts of climate change. Referring to AMAP (2017), Riabova and Klyuchnikova (Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018) argue that this complexity of change will require adaptation at a variety of levels – local, regional, national and global. Leksin and Porfiryev (Reference Leksin and Porfiryev2017) suggest that in the context of the climate change impacts, indigenous communities might need to adjust their methods for maintaining traditional lifestyles such as reindeer herding, fishing and hunting, but also their mobility options.

The elements of adaptive capacity

The development of the adaptive capacity framework reveals that several aspects and contextual factors influence a community’s ability to adapt to climatic and non-climatic changes. The literature recognises that local adaptive capacity depends on a set of available and interdependent aspects: different forms of capital, distribution and access to resources, as well as the structure of institutions (e.g. Bay-Larsen, Risvoll, Vestrum, & Bjørkhaug, Reference Bay-Larsen, Risvoll, Vestrum and Bjørkhaug2018; Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Smit, Duerden, Ford, Goose and Kataoyak2010; Smit & Pilifosova, Reference Smit, Pilifosova, McCarthy, Canziani, Leary, Dokken and White2001 cited in Keskitalo et al., Reference Keskitalo, Dannevig, Hovelsrud, West and Swartling2011). These aspects are also described in the literature as determinants, indicators and/or capitals of adaptive capacity. They can be grouped in objective and subjective dimensions or, as described by Armitage (Reference Armitage2005), as fast-moving and slow-moving attributes, respectively (Armitage, Reference Armitage2005, p. 707).

While objective aspects, such as infrastructure, technology and economic assets, were already identified in the Third Assessment IPCC report (Smit & Pilifosova, Reference Smit, Pilifosova, McCarthy, Canziani, Leary, Dokken and White2001 in Keskitalo et al., Reference Keskitalo, Dannevig, Hovelsrud, West and Swartling2011), the role of subjective and/or socio-cognitive ones in shaping adaptive capacity received greater attention in more recent years (Bay-Larsen et al., Reference Bay-Larsen, Risvoll, Vestrum and Bjørkhaug2018; Blennow & Persson, Reference Blennow and Persson2009; Goldhar, Bell, & Wolf, Reference Goldhar, Bell and Wolf2014). Local adaptive capacity can now be “conceptualised as the sum of objective and subjective dimensions, where the adaptive capacity is latent under the former and activated under the latter,” (Berman, Kofinas, & BurnSilver, Reference Berman, Kofinas, BurnSilver, Fondahl and Wilson2017 in Tiller and Richards, Reference Tiller and Richards2018).

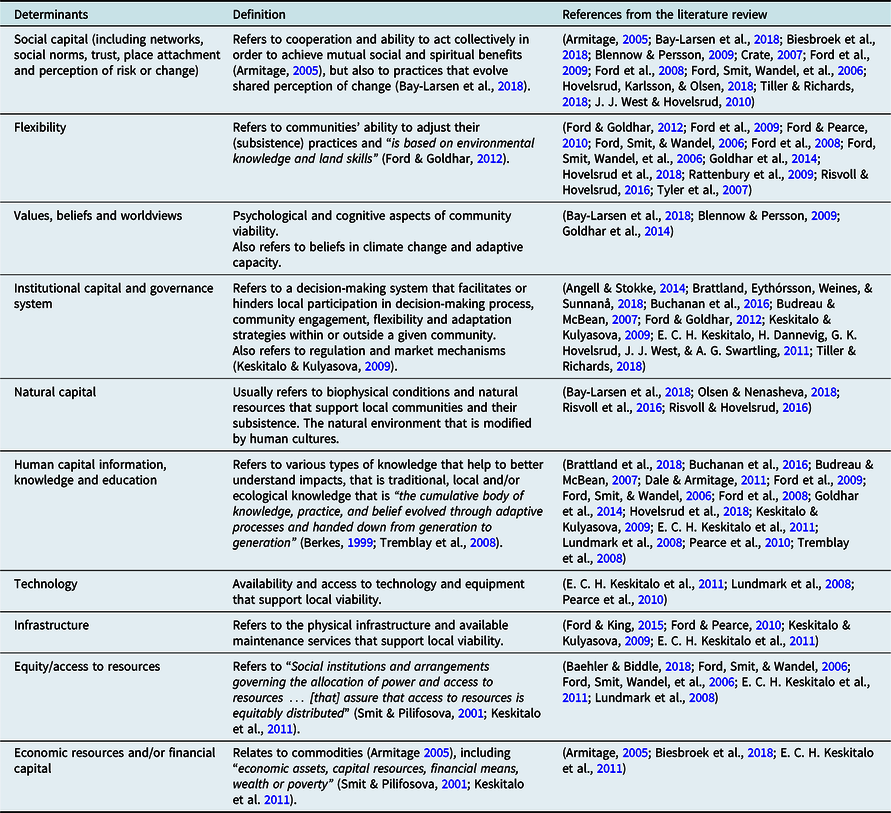

Those aspects or determinants of adaptive capacity vary over time and location. Table 2 presents those determinants that were identified in the literature, describes their meanings and presents references to the reviewed literature. Following the presentation of those determinants, they were grouped under 10 categories such as social capital, flexibility, worldviews, institutions, natural capital, human capital, technology, infrastructure, equity and economic resources.

Table 2. Categories of the determinants of adaptive capacity, their definitions and references to the literature.

It is important to note the complexity of the relationships between adaptive capacity and adaptation (e.g. O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Eriksen, Sygna and Naess2006), as the presence of any particular determinant does not necessarily strengthen local adaptive capacity and/or lead to adaptation (e.g. Ford & King, Reference Ford and King2015). For example, Keskitalo et al. (Reference Keskitalo, Dannevig, Hovelsrud, West and Swartling2011) suggest that economic resources, infrastructure and technology may be made inaccessible by high-maintenance costs. In fact, determinants can even weaken adaptation. For example, some scholars have argued that while financial resource and/or technology can enhance the adaptive capacity, they may simultaneously not be available for some households (Ford & Pearce, Reference Ford and Pearce2010) and can increase the dependency on those determinants (Keskitalo et al. Reference Keskitalo, Dannevig, Hovelsrud, West and Swartling2011).

The question of enhancing adaptive capacity, and more specifically its translation into adaptive actions, was further developed by Ford and King (Reference Ford and King2015) and Ford et al. (Reference Ford, Couture, Bell and Clark2018) who examine and identify the necessity of governance factors that enable adaptation to take place. They present interdependent institutional factors that lead to adaptation: political leadership on adaptation, institutional organisation, decision-making and stakeholder engagement, availability of usable science, funding and public support (Ford & King, Reference Ford and King2015). Yet, even with this knowledge, policy mechanisms, dilemmas and trade-offs in the implementation stages can weaken local adaptive capacity (Risvoll, Fedreheim, & Galafassi, Reference Risvoll, Fedreheim and Galafassi2016).

In addition to determinants and adaptation readiness, literature identifies several contextual factors and cross-scale processes that are not strictly a part of adaptive capacity, but can complicate the effectiveness of community’s ability to adapt to changing conditions (C. T. West, Reference West2011) and may also affect local exposure to changing conditions (Ford, Smit, & Wandel, Reference Ford, Smit and Wandel2006). The following factors are identified as follows: demographic trends like gender and its societal roles (Buchanan, Reed, & Lidestav, Reference Buchanan, Reed and Lidestav2016; Bunce, Ford, Harper, Edge, & Team, Reference Bunce, Ford, Harper, Edge and Team2016; Goldhar et al., Reference Goldhar, Bell and Wolf2014; Tomaska, Reference Tomaska2015), population structure (Lundmark, Pashkevich, Jansson, & Wiberg, Reference Lundmark, Pashkevich, Jansson and Wiberg2008), youth participation and engagement (MacDonald, Ford, Willox, Mitchell, & Productions, Reference MacDonald, Ford, Willox, Mitchell and Productions2015), the type of community (Armitage, Reference Armitage2005) and the area’s political and socio-economic situation (Keskitalo, Reference Keskitalo2009; Kvalvik et al., Reference Kvalvik, Dalmannsdottir, Dannevig, Hovelsrud, Rønning and Uleberg2011), including market conditions and globalisation (Keskitalo & Kulyasova, Reference Keskitalo and Kulyasova2009). Wesche and Chan (Reference Wesche and Chan2010) underline that food security also influences local adaptive capacity (see also Fillion et al., Reference Fillion, Laird, Douglas, Van Pelt, Archie and Chan2014).

Several scholars stress the scale and/or variables of adaptive capacity, stating, “adaptive capacity is nested … in cross-scale societal processes that may hinder or enable action,” (AMAP, 2017 in Hovelsrud et al., Reference Hovelsrud, Karlsson and Olsen2018). Here, O’Brien et al. (Reference O’Brien, Eriksen, Sygna and Naess2006) argue that local adaptive capacity may differ from national adaptive capacity due to the diversity between these scales. The scale of change itself and the scale of decision-making can influence the scope of adaptation (Armitage, Reference Armitage2005; J. J. West & Hovelsrud, Reference West and Hovelsrud2010), while Tiller and Richards (Reference Tiller and Richards2018) argue that stakeholders and stakeholder groups will have to adapt to different levels of change.

Shipping as an emerging change

This literature review indicates that many selected studies examine adaptive capacity in the context of climatic and non-climatic change. It is also acknowledged that communities do not adapt to climate change in isolation from other changes (e.g. J. J. West & Hovelsrud, Reference West and Hovelsrud2010). Thus, in describing adaptive capacity, the focus is given to the interplay of multiple cross-scale changes (e.g. Rattenbury, Kielland, Finstad, & Schneider, Reference Rattenbury, Kielland, Finstad and Schneider2009). Prno et al. (Reference Prno, Bradshaw, Wandel, Pearce, Smit and Tozer2011, p. 17) describe climate change as an additional factor in societal changes already occurring and argue that the impacts of climate change present “a minor concern, outweighed by [other] social issues…”.

In relation to this study, shipping growth is also considered to be a kind of changing condition in the reviewed literature. However, the examination of this emerging development with application of the adaptation and adaptive capacity framework is rather deficient.

About 15% of selected articles for this literature review refer to shipping a developing industry in the Arctic. The majority of these studies were published during the past decade and connect shipping development to changing ice conditions (e.g. Andrachuk & Smit, Reference Andrachuk and Smit2012; Christie, Hollmen, Huntington, & Lovvorn, Reference Christie, Hollmen, Huntington and Lovvorn2018; Ford et al., Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012; Ford & Goldhar, Reference Ford and Goldhar2012) as well as industrial activities, including tourism (e.g. Andrachuk & Smit, Reference Andrachuk and Smit2012; Olsen & Nenasheva, Reference Olsen and Nenasheva2018). In reference to assessment reports (ACIA, 2005; AMAP, 2011), Riabova and Klyuchnikova (Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018) explain that rapid changes in the cryosphere enable better navigation in previously sea-bounded areas.

Shipping in this context is described as an “economic opportunity” of climate change (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Couture, Bell and Clark2018; Ford & Goldhar, Reference Ford and Goldhar2012) with the potential to influence local economies of northern settlements (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Hollmen, Huntington and Lovvorn2018), contribute to local value creation (Olsen & Nenasheva, Reference Olsen and Nenasheva2018) and provide employment opportunities (Angell & Stokke, Reference Angell and Stokke2014). However, few studies have examined these opportunities and how they should be managed (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012). Moreover, not all coastal communities will benefit from this development as port infrastructure and local water deepness present crucial aspects of accommodating shipping during the ice-free season (Andrachuk & Smit, Reference Andrachuk and Smit2012).

In addition to opportunities, scholars underline that there are some risks associated with increased shipping. Riabova and Klyuchnikova (Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018, referring to Davydov & Mikhailova, Reference Davydov and Mikhailova2011) give the example of risks from ship traffic passing through Vaygach Island in the Russian Arctic. They argue that the community is increasingly accessible to ship traffic and visitors that exchange imported goods for local natural traditional resources. This trend has resulted in the changes of traditional economy and exploitation of natural resources (ibid). Based on the examination of shipping impacts on community of Solovetsky, Olsen and Nenasheva (Reference Olsen and Nenasheva2018) argue that growth in the number of passenger vessels has led to a significant increase in the absolute number of tourists and thus overcrowding. The same study suggests that overcrowding may be perceived as a source of disturbance, and increased pressure on existing building and transport infrastructure and waste facilities that were originally designed to cover basic community needs (ibid.) Shipping can also have negative impacts on Arctic natural environments and sensitive ecosystems (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Couture, Bell and Clark2018; O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Eriksen, Sygna and Naess2006) including those inhabited by marine mammals (Bunce et al., Reference Bunce, Ford, Harper, Edge and Team2016; Christie et al., Reference Christie, Hollmen, Huntington and Lovvorn2018).

Ford et al. (Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012) refers to Cameron (Reference Cameron2012) and argue that “shipping and resource development are likely to be major factors affecting vulnerability and adaptation in Arctic communities.” Olsen and Nenasheva (Reference Olsen and Nenasheva2018) also identify several salient determinants of adaptive capacity for the community of Solovetsky, such as local involvement in shipping decision-making, infrastructure, local values, the natural environment and economic resources. The authors argue that adaptive capacity is also shaped by the interlinkages of the determinants, as they may lead to trade-offs and or co-beneficial support (ibid.)

Discussion

Development of the adaptive capacity framework

The results captured by this study illustrate that the adaptive capacity framework (at the community level) has developed significantly during the past two decades (e.g. Ford et al., Reference Ford, Couture, Bell and Clark2018) in regards to Western scholarly traditions. The adaptation framework (at the community level) its later recognition by Russian scholars (Riabova & Klyuchnikova, Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018), however, the selected studies are developed around the concept of adaptation rather than the concept of adaptive capacity.

In general, the adaptive capacity framework applied to study Arctic communities in the context of climatic and non-climatic changes has advanced theoretically and methodologically. This has been occurred most significantly by Western scholars, particularly after the publication of the Third Assessment Report by IPCC in Reference McCarthy, Canziani, Leary, Dokken and White2001. As such, this framework is useful for understanding community aspects that support, activate or hinder local adaptation in response to impacts from climate change and other changing conditions. In line with Mortreux and Barnett (Reference Mortreux and Barnett2017), I argue that the development of adaptive capacity framework can be divided into two overlapping paths that have been developed in parallel, rather than sequentially. The first path is characterised by the development of the concept and its relationship with other community characteristics, such as vulnerability, resilience, adaptation and sustainability. It is also defined by its establishment of methodological perspectives and by its examination of local factors or contexts (also known as determinants and capitals) and their roles. The second path questions the role of determinants in enhancing a community’s ability to adapt to new and emerging cross-scale changes, both climatic and non-climatic, such as shipping growth. I align myself with earlier scholars’ findings that the determinants are context dependent, and that there is a need to examine those determinants and their interrelations in order to assess local adaptive capacity.

In terms of the applied methodology, the majority of Western studies were qualitative, single case study research designs, with only a few establishing multiple cases within and outside the Arctic region. The literature review process revealed that Russian studies are characterised by three main methodological differences. First, the unit of analysis in studies published by Russian scholars pertain mostly to individual capacity (usually refers to health conditions) in the context of harsh Arctic climatic conditions and to the regional or sectorial capacity to adapt to climatic. Those units of analysis are not considered in this review – that is, local level communities. In contrast with Western studies, the local community level – where the impacts are often first felt – is not yet thoroughly explored by Russian scholars (Lopulenko, Reference Lopulenko2009; Riabova & Klyuchnikova, Reference Riabova and Klyuchnikova2018, p. 110). However, I would not argue that those studies do not exist. I would rather suggest that the Western-developed vocabulary of adaptation studies is not always used in studies that describe the impacts of changes taking place in Russian local communities.

The second issue relates to how the adoption of the adaptive capacity framework in community-based research by Russian scholars has been challenged by the use of Western terminology to describe the empirical reality (Olsen & Nenasheva, Reference Olsen and Nenasheva2018; Stammler-Gossmann, Reference Stammler-Gossmann, Hovelsrud and Smit2010). Even though the selected studies describe communities’ abilities to adapt to multiple changes, a standard framework of terminology is not necessarily applied in Russian. As described in the Methodological section, the term adaptive capacity can be translated into Russian in three different ways, and a test search identified that all three translations are commonly used by Russian scholars. For example, the Russian translation of the IPCC’s AR5 Synthesis report (IPCC, Reference Field, Barros, Dokken, Mach, Mastrandrea, Bilir and White2014) uses at least two of these variations (“sposobnost” and “potencial”) to refer to adaptive capacity. A concept of adaptive capacity as a social attribute of local communities is not explicitly used in Russian studies. Moreover, compared to other Arctic nations, Russia was late to address some of the climate change measures, including adaptation. For example, Russia issued a national plan for adaptation in December, 2019 (The Russian Government, 2019). Hence, I would argue that there is a possibility that several community-based studies in Russian described community responses to climatic and non-climatic changes without using the adaptation and/or adaptive capacity approach.

The third methodological limitation in pan-Arctic research, one which influences the scope of reviewed literature, is the definition of the Arctic. The geographical boundaries of the Russian Arctic region, that are described by the western researcher (e.g. AHDR, AMAP), differs from those defined by Russian authorities (Arctic Council, 2017; The President of the Russian Federation, 2014). Moreover, the published studies by the Russian authors do not necessarily use the term “Arctic” to describe the geographical area of their research, but rather substitute it with a term “North”.

It is important to understand that the methods applied in any literature review create limitations with implications for the study results. To be more specific, a systematic literature review that includes only peer-reviewed journal articles overlooks important resources, such as government reports, technical papers and conference proceedings (Ford et al., Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012). The last category, in particular, could offer a unique source of information, especially in the Russian case (many research results from eLIBRARY.ru’s database were published in the form of conference proceedings). Moreover, a significant portion of scientific results are published in assessments reports (e.g. AMAP, 2011; AMAP, 2017; IPCC, Reference McCarthy, Canziani, Leary, Dokken and White2001, Reference Parry, Canziani, Palutikof, van der Linden and Hanson2007, Reference Field, Barros, Dokken, Mach, Mastrandrea, Bilir and White2014; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Hovelsrud and Gearheard2014) and anthologies that provide a stronger synthesis of adaptive capacity’s theoretical development (e.g. Fondahl & Wilson, Reference Fondahl and Wilson2017; Hovelsrud & Smit, Reference Hovelsrud and Smit2010). This type of literature may also present several determinants, capitals and/or factors of adaptive capacity that are not listed in Table 2. However, some of these results and conclusions were cited by the authors in the selected literature, and thus are partially reflected in this study. Further studies may overcome this limitation by extending the inclusion of other sources of scientific literature.

Understanding adaptive capacity through shipping growth

It must be reiterated that shipping development is described in the reviewed literature as a result of climatic and socio-economic changes in the Arctic, but also as a contributor to changes in local communities. As such, Arctic shipping development presents new opportunities and risks for Arctic communities. The reviewed literature describes both positive and negative impacts on environmental, sociocultural and economic realities.

The results of this review also align with existing studies that describe increasing shipping in the opening Arctic as a new concern for coastal communities (see, for example, Davydov & Mikhailova, Reference Davydov and Mikhailova2011; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Carter, Luijk, Parker, Weber, Cook and Provencher2020; Dawson, Stewart, Johnston, & Lemieux, Reference Dawson, Stewart, Johnston and Lemieux2016; Olsen, Carter, & Dawson, Reference Olsen, Carter and Dawson2019; Olsen, Hovelsrud, & Kaltenborn, Reference Olsen, Hovelsrud, Kaltenborn, Pongrácz, Pavlov and Hänninen2020; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Dawson and Johnston2015). Shipping development brings new (usually seasonal) economic opportunities to communities, which, in combination with other factors, may present a trade-off. Hence, we can use these studies to discuss the risks and opportunities that Arctic communities experience in the context of multiple changes.

Moreover, shipping trends are predicted to increase in regions with projected sea ice decline and increasing demand for shipping operations (Smith & Stephenson, Reference Smith and Stephenson2013 in Ford et al., Reference Ford, Couture, Bell and Clark2018). This prognosis for the future of Arctic shipping operations might challenge the examination of future adaptive capacity and local adaptation to ship traffic. Given the rate of change in the Arctic, in a line with Ford et al. (Reference Ford, Bolton, Shirley, Pearce, Tremblay and Westlake2012), I would argue that more knowledge is needed to understand how changes in industries like shipping affect communities’ experiences and responses to climate change.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have performed a review of developments in adaptive capacity research on local Arctic communities in the context of climatic and non-climatic change, in particular, examining if and how the shipping development is addressed in those studies. The results of this review lead to three main conclusions.

First, the study illustrates that the framework has been significantly developed theoretically and methodologically since inception. The review illuminates the diversity of contextual determinants of adaptive capacity, arguing that their availability might strengthen adaptive capacity and lead to adaptation when activated. However, the relationship between any given determinant of adaptive capacity may result in trade-offs that weaken a community’s overall adaptive capacity. Second, this study describes several challenges for the inclusion of Russian language literature on the subject in a review process. Hence, it is important to mention that even though the adaptation framework has been used by Russian scholars throughout recent decades, the results of this research are yet to be integrated into the pan-Arctic research. Finally, studying local communities as a unit of analysis provides first-hand knowledge about emerging changes, as they are often the first to feel the concrete impacts of global and national changes – this makes such communities important stakeholders in adaptation responses and research.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledge Grete K. Hovelsrud, Kathinka F. Evertsen and Camilla Risvoll for reviewing and providing valuable comments to the earlier versions of the paper and Malinda Labriola and Nikolai Holm for providing language help. I am particularly appreciative of the comments by the two anonymous reviewers that helped significantly to improve the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.