Multilateral treaties negotiated by and open for signature to all members of the United Nations (UN) represent important foreign policy tools used by states to manage global problems by overcoming collective action problems, reducing costs of negotiating separate iterated treaties, and generally advancing overlapping interests common to all states (Keohane Reference Keohane1984). These treaties address a wide range of areas including human rights issues, which seek to protect vulnerable populations like women, racial minorities, children, migrants, refugees, and disabled people, just to name a few. For example, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) establishes minimum requirements for women’s rights across social, political, and economic areas and seeks to ensure women’s access and equality among signatories. Multilateral human rights treaties like CEDAW are important because they work to improve conditions for marginalized groups addressing collective humanitarian problems on an international scale. Given the importance of these agreements, it is crucial to understand the factors that lead states to join these agreements, not only by signing, but also ultimately ratifying them.

There have been recent efforts to better understand when and why states will commit to multilateral human rights agreements. Recent scholarship has examined why certain countries or regions may be more likely to ratify multilateral agreements (Schulz and Levick Reference Schulz and Levick2023) or how actors outside the legislature may matter in the domestic ratification process (Böhmelt Reference Böhmelt2018; Koubi, Mohrenberg, and Bernauer Reference Koubi, Mohrenberg and Bernauer2020). Despite the fact that treaty ratification is a domestic procedure, often requiring legislative consent, little research has asked whether who sits in the legislature should matter for state ratification behavior of human rights treaties (Haftel and Thompson Reference Haftel and Thompson2013; Kelley and Simmons Reference Kelley and Simmons2015; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000; Peake Reference Peake2017; Simmons Reference Simmons2009). We draw on research about elected women’s distinct domestic (Barnes Reference Barnes2012; Htun Reference Htun2016; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010) and foreign (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Bendix and Jeong Reference Bendix, Jeong, Friedrichs and Tama2024; Best, Shair-Rosenfield, and Wood Reference Best, Shair-Rosenfield and Wood2019; Imamverdiyeva et al. Reference Imamverdiyeva2021; Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017; Stauffer et al. Reference Stauffer, Kobayashi, Martin-Morales, Lankes, Heinrich and Goodwinforthcoming) policy preferences to argue that states with greater levels of women’s legislative representation should be more likely to ratify multilateral human rights treaties.

Specifically, we argue that women legislators may prioritize the ratification of human rights treaties because of their shared gendered experiences of exclusion and discrimination. These shared experiences may make women legislators more likely to advocate on behalf of marginalized groups on an international scale, acting as transnational surrogate representatives (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). Additionally, women may have domestic reasons for promoting human rights treaty ratification because these treaties tend to overlap similar policy initiatives that they prioritize in their domestic work. Because women legislators prioritize policies aimed at improving the lives of marginalized groups domestically (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2014; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010), they may also seek to ratify human rights treaties with similar aims as these treaties may allow them to leverage their domestic policy preferences (Woo and Ryu Reference Woo and Ryu2023). As women’s representation has increased around the world, it is important to understand how these gains in women’s representation affect patterns of international cooperation surrounding human rights issues.

To test this hypothesis, we compile a newly expanded, original dataset of the ratification of 201 global multilateral treaties from 1947 to 2016. These treaties are classified as human rights versus non-human rights agreements. We show that the proportion of women in the legislature is associated with an increased likelihood of human rights treaty ratification.

These findings indicate that women’s legislative representation does have important foreign policy implications in determining whether states sign on to certain treaty initiatives. Specifically, our findings underscore that women do have distinct foreign policy preferences, and these preferences extend to issues that are not overtly gendered in nature (Betz, Fortunato, and O’Brien Reference Betz, Fortunato and O’Brien2023). Women in domestic legislatures are willing to advocate on behalf of the interests and rights of a broad range of vulnerable populations. Additionally, these findings have practical implications for humanitarian initiatives. As women’s representation continues to increase globally, we should see an increase in states that sign onto human rights treaties. While the direct humanitarian impact of these measures is a topic of scholarly debate, we follow Simmons (Reference Simmons2009) and argue that signing onto these treaties in the first place is a crucial first step in ensuring the protection of human rights when supporting domestic factors are present.

Impact of Domestic Actors on Foreign Policy Outcomes

Scholars in international relations are beginning to explore the implications that women’s legislative presence and political participation may have for state foreign policy. Specifically, women tend to oppose the use of force in conflicts, and women’s legislative presence is typically associated with a decrease in defense expenditures (Bendix and Jeong Reference Bendix, Jeong, Friedrichs and Tama2024; Clayton and Zetterberg Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018; Conover and Sapiro Reference Conover and Sapiro1993; Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011). Higher levels of women’s legislative presence are also associated with reaching peace agreements in civil conflicts (Best, Shair-Rosenfield, and Wood Reference Best, Shair-Rosenfield and Wood2019). Additionally, women tend to be more sensitive to humanitarian concerns, particularly the need to protect the welfare of vulnerable populations like women and children (Brysk and Mehta Reference Brysk and Mehta2014; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). When these populations are threatened, women are more likely to advocate for humanitarian military interventions (Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). Women are also more likely to advocate for more pro-feminist foreign policies in the legislature, addressing issues like sexual assault in the military, gender violence during conflict, and provision of humanitarian aid to vulnerable populations (Aggestam and True Reference Aggestam and True2020; Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Bashevkin Reference Bashevkin2014). Finally, women in the legislature are also more likely to support trade liberalization foreign policy (Imamverdiyeva et al. Reference Imamverdiyeva2021), although Betz, Fortunato, and O’Brien (Reference Betz, Fortunato and O’Brien2023) find that women legislators may favor more protectionist trade policies.

Specifically, we focus on how women’s legislative presence may have an impact on the ratification of multilateral human rights treaties. The term “global multilateral treaty” refers to any international agreement whose ratification is open to all members of the UN and whose goal is relevant to all states, rather than a specific region (Elsig, Milewicz, and Stürchler Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011). This definition encompasses treaties in diverse issue areas, from human rights to international trade, the environment, disarmament, financial regulation, and intellectual property. These treaties are one strategic tool that states can use to govern issues that all states share an interest in, like the exploration of outer space (Danilenko Reference Danilenko1989) and other global interests. Multilateral treaties can also be used to create and strengthen preferred norms in sensitive areas such as human rights (Chayes, Chayes, and Mitchell Reference Chayes, Chayes and Mitchell1998), or can be used to reduce transaction costs in complicated issue domains (Keohane Reference Keohane1984; Thompson and Verdier Reference Thompson and Verdier2014). States first sign on to these agreements and then ratify them before they begin complying with multilateral treaties, which is generally a gradual and uneven process that is best viewed over long time horizons (Sikkink Reference Sikkink2017). We focus strictly on the relationship between women’s legislative presence and human rights multilateral treaties, specifically.

According to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, human rights treaties are treaties where “states assume obligations and duties under international law to respect, to protect, and to fulfil human rights” (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2023). Although there are nine so-called core international human rights treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, there are a number of other UN agreements that make up the body of international human rights law.

The ratification of multilateral treaties is a domestic procedure subject to a variety of constraints and potential obstacles (Aggestam and True Reference Aggestam and True2020; Haftel and Thompson Reference Haftel and Thompson2013; Kelley and Simmons Reference Kelley and Simmons2015; Peake Reference Peake2017; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000). There are many domestic factors that may affect the likelihood of human rights treaty ratification. For example, democracies are more likely to ratify human rights treaties as well as countries that have newly transitioned to democracies (Elsig, Milewicz, and Stürchler Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000). New democracies especially may use treaty ratification as a way to signal credibility on democratic issues, like human rights, internationally. Additionally, left-leaning governments may be more likely to support the ratification of human rights treaties. Similarly, states that have higher human rights standards already in place domestically may be more likely to ratify human rights treaties because they can more easily comply with the legal requirements of the treaty (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). In this respect, there are several domestic factors that may influence treaty ratification.

Indeed, in many countries, it is common for the national legislature to be formally involved in treaty ratification (Lantis Reference Lantis2009). For this reason, we argue that the composition of domestic legislatures should influence patterns of multilateral treaty ratification. Arguably, the question of who sits in the legislature matters more for treaty ratification than for other international outcomes, such as crisis bargaining and international conflict, where leaders often have the exclusive freedom to issue threats and initiate uses of military force. In countries where ratification is subject to legislative approval, typically at least majority consent in one legislative body — sometimes more — is required for a state to officially ratify a multilateral treaty (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). This means that ratification is a complex legislative process by which legislators must bring certain treaty agreements before legislative committees to place them on the legislative agenda. Treaties that make it out of the committee stage may be put to a floor debate where they may be voted on for ratification. This process requires legislators who support these measures to shepherd them through each stage. Thus, treaty ratification is clearly affected by domestic actors, particularly by those within legislative institutions who can directly influence this process.

Previous work that examines the role of domestic actors in foreign policy outcomes demonstrates that the racial and gender identities of legislators can, indeed, have an impact on various foreign policy outcomes (Aggestam and True Reference Aggestam and True2020; Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Lorber Reference Lorber, Ngan-Ling Chow, Texler Segal and Tan2011; Wilson Reference Wilson, Webster and Sell2014). We build on this research and argue that who is in power when a multilateral human rights treaty is open for signature matters for ratification. Specifically, women’s presence in domestic legislatures might help to explain patterns of human rights treaty ratification across states (Böhmelt Reference Böhmelt2018; Ryckman Reference Ryckman2016; Vreeland Reference Vreeland2008). We argue that women legislators have the ability to influence the ratification process from within the legislature. Although previous scholarship investigates the effect of women’s legislative representation across several foreign policy outcomes (Hessami and da Fonseca Reference Hessami and da Fonseca2020), we know less about the effect of women’s legislative presence on international cooperation (although see Woo and Ryu Reference Woo and Ryu2023). Given the recent increases in women’s legislative representation and the importance of international cooperation, it is important to understand whether women’s legislative presence has an effect on the ratification of certain multilateral treaty initiatives.

Women Legislators and Human Rights Treaty Ratification

As we highlight, women domestic actors have distinct foreign policy preferences across a whole host of foreign policy outcomes (Bashevkin Reference Bashevkin2014; Best, Shair-Rosenfield, and Wood Reference Best, Shair-Rosenfield and Wood2019; Betz, Fortunato, and O’Brien Reference Betz, Fortunato and O’Brien2023; Brysk and Mehta Reference Brysk and Mehta2014; Conover and Sapiro Reference Conover and Sapiro1993; Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). This includes foreign policy outputs, like trade liberalization policy, which are traditionally less overtly gendered (Betz, Fortunato, and O’Brien Reference Betz, Fortunato and O’Brien2023). We argue that women may have similar distinct preferences for certain forms of international cooperation. Specifically, we argue that women legislators might place a higher priority on ratifying certain types of multilateral treaties like human rights treaties. Women may be more inclined to promote human rights treaties because of their shared gendered experiences as women (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Best, Shair-Rosenfield, and Wood Reference Best, Shair-Rosenfield and Wood2019; Betz, Fortunato, and O’Brien Reference Betz, Fortunato and O’Brien2023; Brysk and Mehta Reference Brysk and Mehta2014; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). These shared experiences may motivate women to promote these interests internationally, as transnational surrogate actors, on behalf of certain groups. Additionally, human rights treaties have domestic policy implications that align with the policy issues that women tend to prioritize in their domestic work. Because of this overlap, we argue that women in the legislature might place a higher priority on the ratification of human rights treaties over other types of treaties.

Human rights treaties are international cooperation agreements that include provisions to improve the lives of excluded groups and protect the rights of vulnerable populations from things like discrimination and violence on an international scale. These particular multilateral treaties aim to coordinate state policies across issues that disproportionately affect marginalized and vulnerable populations. We argue that women’s shared experiences of exclusion, vulnerability to violence, and discrimination may make them more inclined to promote the ratification of human rights treaties that aim to combat these issues for vulnerable populations on an international scale (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Best, Shair-Rosenfield, and Wood Reference Best, Shair-Rosenfield and Wood2019; Betz, Fortunato, and O’Brien Reference Betz, Fortunato and O’Brien2023; Brysk and Mehta Reference Brysk and Mehta2014; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). We acknowledge that women, as a group, represent a diverse group with crosscutting interests and identities (Weldon Reference Weldon2002). Although all women may not share the same experiences, most women share experiences that come with being members of a vulnerable, marginalized group.Footnote 1

Women have traditionally and historically been excluded from positions of political power and inclusion, which gives way to gendered experiences of discrimination (Htun Reference Htun2016; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). Women are often more vulnerable to violence and disproportionately make up the majority of the world’s poor (Angevine Reference Angevine2017). Additionally, women often bear the disproportionate burden of raising children, as well as caregiving responsibilities in general (Brysk and Mehta Reference Brysk and Mehta2014; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). These shared gendered experiences generate shared political interests for women (Beckwith Reference Beckwith2011). Given that shared experiences of gender-based discrimination and exclusion are often to the detriment of women’s human rights, well-being, and livelihood, we might expect that when women enter positions of political power, they will support international efforts that aim to protect the rights and inclusion of vulnerable groups. We expect women legislators to promote the ratification of human rights treaties specifically because these agreements are aimed to alleviate the discrimination of, violence against, and exclusion of vulnerable groups.

In fact, these same shared experiences that may make women more likely to advocate for human rights treaties have been documented to influence their domestic policy work in a similar direction. Women’s shared experiences of exclusion, discrimination, and violence make them more likely to advocate for domestic policies that prioritize issues that disproportionately impact the lives of women and other marginalized groups, and work toward the same ends as human rights treaties. Specifically, women tend to advocate for policies that protect the domestic human rights of individuals from state violence (Melander Reference Melander2005) as well as policies that advocate for the interests of women and other marginalized groups who have been historically excluded from formal power like children, minorities, and the elderly (Caminotti and Piscopo Reference Caminotti and Piscopo2019; Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2014; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010). These policy areas tend to include issues like access to reproductive health care, wage equality, education, welfare programs, non-discrimination measures, and assistance programs, to name a few. Women tend to promote these policy interests to a higher degree than men in the types of bills they sponsor, by engaging these issues in legislative floor debates, and in their committee work (Barnes Reference Barnes2012; Htun, Lacalle, and Micozzi Reference Htun, Lacalle and Micozzi2013; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2018). In this way, women legislators have a history of advocating for policies that represent marginalized groups domestically.

Although women’s shared experiences have a documented influence on their domestic policy work, why should we expect these gendered experiences to influence their preferences for certain international policy actions? We posit two reasons for this: 1) shared experiences of discrimination, exclusion, and violence may make women inclined to act on these issues in a global context, leading women legislators to advocate for vulnerable groups beyond their nation-state border, and 2) human rights treaties have domestic policy implications for the issue areas that align with women’s domestic policy priorities. Women might be more likely to prioritize the ratification of human rights treaties over other types of multilateral agreements because they might see these treaties as a means to leverage domestic policies in issue areas they prioritize. We argue that women’s legislative presence may influence human rights treaty ratification through both of these potential, equally plausible, and complementary mechanisms.

First, women may be inclined to act as transnational surrogate representatives of marginalized and vulnerable groups beyond their nation-state borders (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). Surrogate representatives act for the interests of marginalized groups by representing constituents from those groups even if they do not directly electorally represent them (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). This can occur transnationally when members of marginalized groups act for group interests beyond state borders. In fact, there is evidence that both women and members of racial and ethnic minorities exhibit transnational surrogate representation, representing group interests internationally (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Tillery Reference Tillery2017; Wilson and Ellis Reference Clark Wilson and Ellis2014).

As mentioned, women share experiences of gender-based discrimination, exclusion, and vulnerability to violence. These shared experiences may make women inclined to act on behalf of these issues in a global context, advocating for vulnerable groups beyond their nation-state borders even when this is not directly electorally beneficial (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). These shared experiences of discrimination and exclusion foster a global affective tie to similarly vulnerable groups in other countries, creating a sense of responsibility to act on behalf of those groups. For this reason, we expect that women legislators may be more inclined to act as global surrogates on behalf of vulnerable groups in other countries by supporting the ratification of human rights treaties to protect the rights and inclusion of these groups (Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999).

For example, women legislators might advocate for human rights treaties, like the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which aims to protect the dignity and autonomy of individuals with disabilities. Specifically, the CRPD aims to end the discrimination of individuals with disabilities, protect their accessibility to facilities and services, and promote equal opportunities for their full inclusion in society. In this way, the CRPD provides protections for a vulnerable population, individuals with disabilities, on an international scale. In the 113th Congressional session (2013–2014), both Senator Kelly Ayote and Congresswoman Tammy Duckworth advocated for the ratification of the CRPD, highlighting the importance of the protections provided by the CRPD and the impact that US leadership on these issues would have for citizens with disabilities around the world (United States 2014). Specifically, Congresswoman Duckworth cites an example from a visit to Thailand where she observed the challenges that disability groups face in making public buses wheelchair accessible (United States 2014). This example underscores two important points: 1) women advocate for human rights treaties that aim to protect vulnerable populations, and 2) they are willing to advocate for the interests of these groups beyond their nation-state borders. Thus, women legislators are willing to engage in transnational surrogate representation on behalf of marginalized groups.

In addition to these reasons, women may have domestic reasons for prioritizing human rights treaty ratification. Specifically, the domestic policy areas that women prioritize in their legislative work tend to overlap domains covered in human rights treaties. As mentioned, women’s shared experiences of exclusion and discrimination make them more likely to advocate for the interests of marginalized groups in their domestic policy work. In the same way that certain domestic policies address issues that disproportionately promote the interests of women and other excluded groups, human rights treaties include provisions to improve the lives of excluded groups on an international scale. These particular multilateral treaties aim to coordinate state policies across issues that disproportionately affect marginalized groups. For example, CEDAW is a human rights treaty that aims to address discrimination on the basis of sex and ensure women’s equal access to politics, education, healthcare, and employment. Specifically, CEDAW provides domestic policy prescriptions, like the adoption of a paid maternity leave policy, that states who ratify are expected to adopt. For this reason, human rights treaties have implications for domestic policies that disproportionately affect the interests of women and other marginalized groups. Thus, human rights treaties have domestic policy implications for the issue areas that align with women’s domestic policy priorities.

Because human rights treaties have domestic policy implications for issue areas that align with women’s domestic policy priorities, women in the legislature may have additional reasons for placing a higher priority on the ratification of human rights treaties. Women might be more likely to prioritize the ratification of human rights treaties over other types of multilateral agreements because they might see these treaties as a means to leverage domestic policies in issue areas they prioritize. Specifically, ratifying human rights treaties might allow women in the legislature to leverage new domestic policies in these issue areas as they attempt to bring domestic policy in line with treaty provisions. Women might also see these treaties as a way to strengthen and expand existing domestic policies in these areas.

Treaty ratification opens an opportunity for legislators to bring related issues onto the policy agenda by citing provisions of the treaty itself (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). Domestic legislators can point toward these international agreements as justification for introducing new domestic policies in these areas or expanding existing policies. For example, when countries sign onto human rights treaties like CEDAW, women legislators might be able to more effectively advocate for or expand policies that address issues related to women’s well-being, like access to reproductive healthcare. In fact, during a 2006 legislative debate in the Argentine Chamber of Deputies, Deputy Juliana Di Tullio advocated for the ratification of the optional protocol for CEDAW as a means to expand discussion on topics like access to abortion and contraception (Argentina 2006). In her arguments, Di Tullio cited the opportunity to expand an existing policy on access to contraception and that ratification was a potential way to secure new domestic policy on access to abortion in the future.Footnote 2 This example highlights that when women legislators discuss their support for ratifying human rights agreements, they highlight how these agreements will help them secure new — or expand existing — domestic policies that allow them to protect and promote the interests of marginalized groups. Thus, women legislators may view the ratification of human rights treaties instrumentally as a way to leverage certain domestic policies that align with treaty provisions.

In fact, Woo and Ryu (Reference Woo and Ryu2023) make a similar argument in their research regarding the relationship between women’s legislative presence and ratification of women’s rights treaties, narrowly defined as a subset of specific human rights treaties. They argue that women representatives are likely to support the ratification of women’s rights treaties because ratifying these treaties may lead to the implementation of domestic policies that they prioritize as states work to meet treaty obligations. This is because these domestic policies are related to the issue of the treaty. They, indeed, find that women’s legislative presence leads to greater ratification of women’s rights treaties up until a certain threshold.

We expand this argument to apply to a broader set of human rights treaties, arguing that women will be more likely to support these treaties as a way to promote the interests of excluded and marginalized groups more broadly. Specifically, we expect women to be more likely to emerge as critical actors in support of the ratification of human rights treaties for the above reasons. Although women typically maintain a minority status in most legislatures, women acting as critical actors may be able to overcome these constraints and act “either individually or collectively to bring about women-friendly policy change,” independent of the number of women in the legislature (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009, 127). Specifically, women who emerge as critical actors will have the ability to influence the legislative ratification process at any stage in favor of human rights treaty ratification. As women’s representation in legislatures increases, there is a greater likelihood that a critical woman actor will emerge to advocate for the ratification of human rights treaties. Specifically, as women’s representation increases, the pool from which a critical woman actor may emerge also increases (Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017). Therefore, countries should be especially likely to ratify human rights treaties as the proportion of women in the legislature grows.

H1: Women’s legislative representation should have a positive effect on the ratification of human rights treaties compared to treaties in other issue areas.

Research Design

To test the hypotheses outlined above, we use an original, newly expanded dataset on the ratification of 201 multilateral treaties from 1947 to 2016.Footnote 3 Our dataset includes any major treaty open to signature by all UN members. These treaties include those issued by the UN as well as treaties issued by any of the eight specialized UN agencies. Thus, these treaties deal with global concerns rather than regional issues (Elsig, Milewicz, and Stürchler Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011). For example, we would include a global treaty like CEDAW, but we would not include the African Charter for Human and Peoples’ Rights. Additionally, the treaties included must be significantly different from prior agreements (Elsig, Milewicz, and Stürchler Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011). This criterion excludes agreements written to adjust or modify the terms of existing treaties.Footnote 4

Because we are interested in exploring whether women legislators are more likely to ratify certain types of treaties, we categorize the treaties in our dataset by substantive issue areas following Böhmelt (Reference Böhmelt2018). Specifically, we categorize treaties as those that cover human rights issues versus non-human rights treaties. Treaties addressing human rights issues make up 23.3% (47 treaties) of our sample, whereas the rest of the sample (76.7%, 154 treaties) covers non-human rights treaties. These treaties span other substantive issue areas like security treaties, environmental treaties, and trade agreements.Footnote 5

This expanded dataset is necessary for testing the empirical question we ask in this paper. Expanding the temporal range allows us to test the effects of women’s representation on human rights treaty ratification over time. Women’s representation has increased over time as a result of gender quota policies that became popular among political parties and national legislatures during the 1970s through the early 1990s (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2017). By expanding our temporal range prior to the implementation of gender quota policies, we are able to capture how varying levels of women’s representation affect human rights treaty ratification. Thus, we are able to capture periods of time where the level of women’s representation ranges from low levels of representation to higher levels of representation.

The unit of analysis for the study is country-treaty-year. For each treaty, the observation period begins in the year the treaty was opened for signature for all states in existence at that time.Footnote 6 The dependent variable is a binary indicator of ratification. For each country within each treaty, the dependent variable is coded 1 for the year in which the state ratifies the treaty and 0 otherwise. Once a state ratifies the treaty, the observations cease. To examine whether increasing women’s presence in the legislature leads to greater human rights treaty ratification, we divide the treaties into the two substantive categories mentioned above. Specifically, we code human rights treaties as 1 and non-human rights treaties as 0.

Because the mechanisms through which we argue the presence of women in legislatures influences human rights treaty ratification are only relevant for countries where the legislature has at least some control over the ratification process, we limit our analysis to those countries that require legislative approval for ratification. We identified these countries based on information about state ratification procedures from Simmons (Reference Simmons2009) and the Comparative Constitutions Project (Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2014). Country-years are included in the dataset if their state ratification procedures require at least majority consent of one legislative body. Country-years where the individual chief executive or cabinet can make decisions about ratification without gaining legislative approval are excluded from the analysis.

Due to the structure of the dependent variable and the stochastic dependence present in the dataset, we estimate multilevel logistic regressions with time polynomials to model time dependence. We also include random intercepts for country and fixed effects for treaties. Carter and Signorino (Reference Carter and Signorino2010) demonstrate how this model substantively and functionally approximates a variety of traditional survival models, such as Cox Proportional Hazard models, by using a set of time polynomials to estimate the hazard rate, while making interpretation of the results more straight forward and accessible. Specifically, the multilevel logistic regression with time polynomials estimates the likelihood of a given event — in this case, treaty ratification — occurring in a given year. Thus, we are able to interpret the coefficients as either increasing or decreasing the likelihood of ratification occurring in a given year. For example, positive coefficients indicate factors that increase the likelihood of treaty ratification occurring in a given year, whereas negative coefficients indicate factors that should decrease the likelihood of treaty ratification occurring (see Böhmelt (Reference Böhmelt2018) for a recent example of using logistic regression with cubic polynomials to study the effect of Source of Leader Support (SOLS) changes on multilateral treaty ratification). With this modeling strategy in mind, we will be able to determine the effect that higher amounts of women’s representation in parliament will have on the likelihood of ratifying human rights agreements in a given year.

Explanatory Variables

The main independent variable in our analysis is the percentage of women in the state’s single or lower house of parliament. Data for this variable come from the Quota Adoption and Reform over Time (QAROT) dataset (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Paxton, Clayton and Zetterberg2017), which combines data from Paxton, Green, and Hughes (Reference Paxton, Green and Hughes2008) and the Inter-Parliamentary Union (2017). To account for the temporal structure of the data, this variable is lagged one year. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the maximum observed levels of women’s legislative representation within each of the 146 countries in our dataset. The vast majority of countries see moderate levels of women’s legislative representation of 10–20%. In some countries, however, women reach or exceed parity with men (Bolivia and Rwanda).Footnote 7

Figure 1. Maximum observed levels of women’s legislative representation across countries that require legislative consent for treaty ratification.

To examine whether the effect of increasing women’s presence in the legislature increases the likelihood of human rights treaty ratification, we include an interaction between the lagged percentage of women in the national legislature and the binary variable coded 1 for human rights treaties and 0 for non-human rights treaties. This will allow us to investigate whether the relationship between women’s legislative representation and treaty ratification is different for human rights treaties compared to treaties covering other substantive issues like trade, the environment, or security issues. According to our theoretical expectations, we expect to find a positive effect for this interaction, which would indicate that as women’s legislative presence increases, human rights treaties are more likely to reach ratification when compared to other types of treaties.

In addition to this variable, we control for factors that may impact human rights treaty ratification and also affect or correlate with descriptive representation of women. If the same factors that lead to increased women’s legislative representation also correlate with those favorable to human rights treaty ratification, then an observed link between women’s legislative representation and ratification behavior may be epiphenomenal. Although we cannot entirely rule out the possibility of alternative explanations, these control variables capture the most likely candidates for confounding variables.

First, we control for the country’s level of development, operationalized as GDP per capita (Gleditsch Reference Gleditsch2002). Although previous studies have found little evidence of a direct causal link between development and women’s legislative representation, other research suggests development conditions the effects of variables found to be central to explanations of cross-national variation in women’s representation (Rosen Reference Rosen2013). More developed countries may also be more inclined to ratify human rights treaties because wealthier countries will find it easier to modify their policies to comply with obligations set forth in agreements or may already be in compliance before the treaty is signed.

Second, we control for regime type, operationalized as the country’s Revised Combined Polity Score (polity2) from the Polity IV project (Marshall, Gurr, and Jaggers Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2016). Scholars have found that democracy does encourage growth in levels of women’s representation (Paxton, Hughes, and Painter Reference Paxton, Hughes and Painter2010), and democracies are also more likely to ratify human rights treaties (Elsig, Milewicz, and Stürchler Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011). Previous research also suggests new democracies in particular are more likely to ratify human rights treaties in an effort to “lock in” domestic reforms (Elsig, Milewicz, and Stürchler Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000). We modify coding developed by Moravcsik (Reference Moravcsik2000) to categorize a country in a given year as being a new democracy or not. We code a country to be a new democracy in a given year if they are currently democratic, earning a polity score of seven or greater for the current year, but have not been continuously democratic for at least five years preceding. This captures the idea that as countries are newly democratized, they are more incentivized than other countries to demonstrate their commitment to certain values associated with being democratic such as increasing women’s representation in parliament and signing on to human rights treaties.

Next, we control for a state’s human rights score. Following Crabtree and Fariss (Reference Crabtree and Fariss2015), we include a latent measure of state respect for human rights. States that score higher on this latent measure of respect for human rights may have many of the legal requirements needed to comply with existing human rights treaties which, in turn, may make these states more likely to ratify human rights agreements (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). Additionally, some scholars argue that documented correlations between women’s representation and foreign policy outcomes are a product of the general level of gender equality in a given state, rather than the impact of individual women legislators whose policy priorities may differ from men’s (Brysk and Mehta Reference Brysk and Mehta2014; Lu and Breuning Reference Lu and Breuning2014). States with greater respect for human rights likely also place a greater value on societal gender equality and, as a result, may elect more women to office (Bush Reference Bush2011). By including a latent human rights score for each state, we can control for the fact that states with greater respect for human rights may be both more inclined to ratify human rights treaties and may elect more women to their legislatures.

Additionally, we control for partisanship of the government. Left-leaning parties tend to send more women to parliament than right-leaning parties, particularly when gender quotas are not imposed (Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008), and left-leaning parties may also be more supportive of multilateral treaties, especially human rights treaties. Thus, a higher proportion of women in the legislature could indicate a left-leaning government that prefers human rights initiatives. To isolate the effect of women representatives from larger partisan forces, then, we include a measure of the government’s political orientation. To operationalize this variable, we rely on information from the 2017 Database of Political Institutions to code whether the largest government party is on the left with respect to economic policy (communist, socialist, Christian democratic, or left-wing) as of January 1 of the given year (Cruz, Keefer, and Scartascini Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2018).

We also control for the extent of a country’s dependence on foreign aid. Countries that are highly dependent on foreign aid are more likely to adopt gender quotas as a signaling device (Bush Reference Bush2011). Hence, countries with high foreign aid dependence should display higher levels of women’s representation. Meanwhile, states that depend on foreign aid may also experience pressure from donors to engage in human rights cooperative efforts, which would result in a higher propensity for human rights treaty ratification. We follow Bush (Reference Bush2011) in operationalizing foreign aid dependence as the natural log of the amount of official development assistance received from Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in the previous year.

Finally, we control for the total number of human rights treaties that a state has ratified up until a given year. Countries that have previously ratified a large number of human rights agreements may be more likely to ratify an additional agreement in the future. As mentioned above, this is because as states comply with the legal requirements of each additional human rights treaty, they may be able to more easily and readily comply with the requirements of additional treaties in the same issue area (Simmons Reference Simmons2009). Thus, we are able to isolate the effect of women’s representation on the likelihood that an additional human rights treaty is ratified, independent of that country’s history of human rights treaty ratification.

Results

Table 1 reports results from our main analysis designed to test the impact of women’s legislative representation on human rights treaty ratification.Footnote 8 Model 1.1 presents our model without covariates, whereas Models 1.2–1.5 present our estimates for the model including our controls. The main variable of interest is the interaction between women’s legislative representation and human rights treaties designed to test whether women’s legislative representation has an effect on the ratification of human rights treaties specifically, over other non-human rights treaties. The coeffcient for the interaction between women’s legislative representation and human rights is positive and statistically distinguishable from zero across all models. This shows that as the percentage of women in parliament increases, countries are more likely to prioritize ratification of human rights treaties specifically. This offers support for our argument that women are more likely to prioritize human rights treaties, which generally seek to improve the lives of women and other marginalized groups. These results support our expectations for H1. Footnote 9

Table 1. Effect of women’s parliamentary representation on human rights treaty ratification

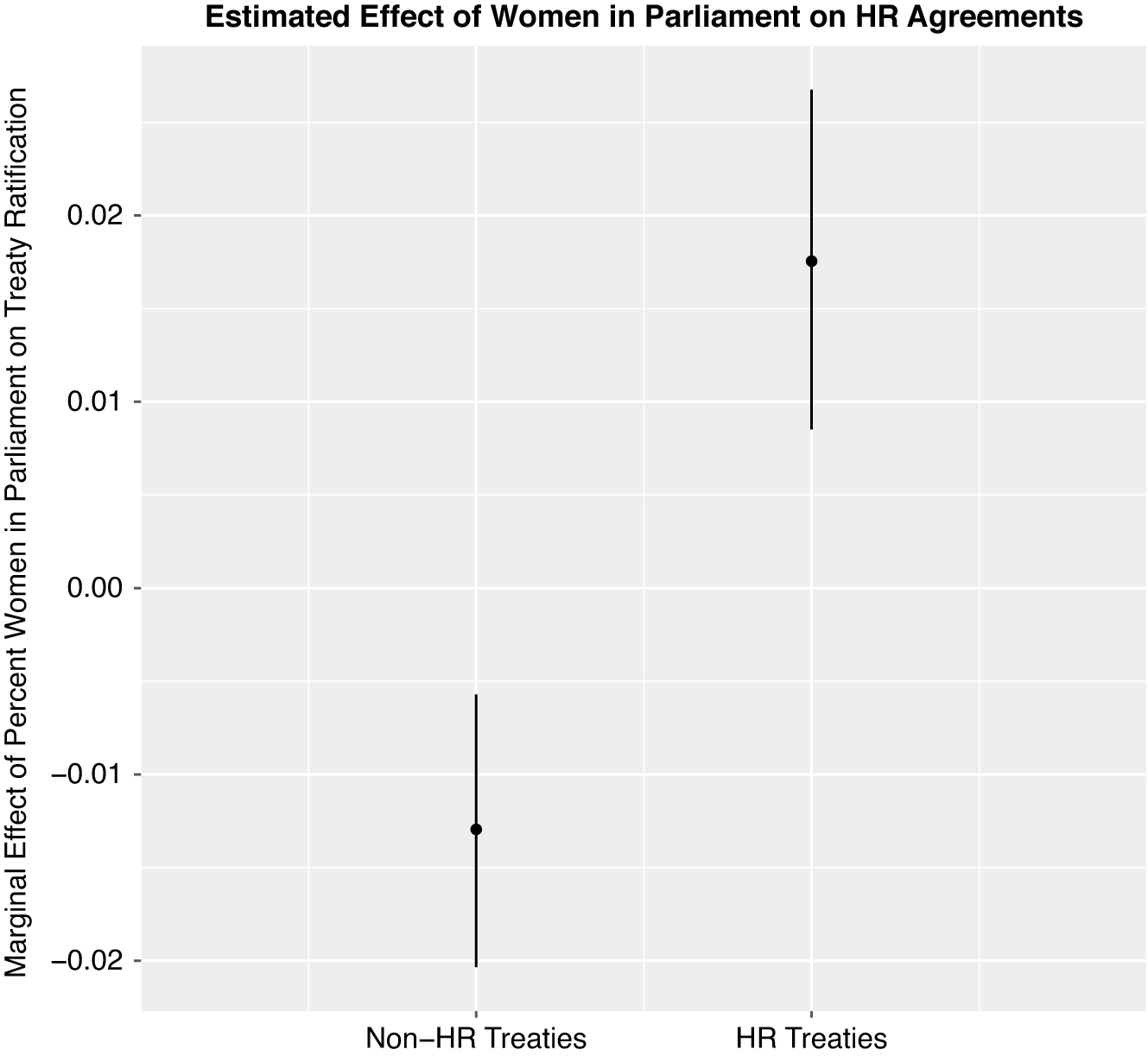

The marginal effects plot in Figure 2 shows the marginal effect of increasing women’s legislative representation on the ratification of human rights and non-human rights agreements, based on estimates from Model 1.5. The marginal effects are calculated using the interplot package in R. This plot demonstrates how the effect of the coefficient of women’s representation on treaty ratification changes for non-human rights and human rights treaties. For human rights agreements, the marginal effect of the coefficient on women’s representation is statistically significant and positive. This means that increasing women’s presence in office has a positive effect on treaty ratification for human rights treaties. Substantively, this marginal effect plot demonstrates that there is a positive relationship between percent women in parliament and human rights treaty ratification, which does not exist for agreements in other issue areas. For non-human rights treaties, the marginal effect of the coefficient on women’s representation is actually negative, meaning that the marginal effect of increasing women’s presence in legislatures has a negative effect on the ratification of treaties in other issue areas.Footnote 10 Overall, this illustration offers further support for our argument that an increase in women’s legislative representation leads to an increase in the likelihood of human rights treaty ratification.Footnote 11

Figure 2. Marginal effect of women’s representation on human rights treaty ratification.

Additionally, we can interpret these findings substantively. As women’s representation increases from 2.63% (one standard deviation below the mean) to 23.71% women (one standard deviation above the mean), the likelihood of human rights treaty ratification increases by 9.2%. This is a fairly substantial increase, all else equal.Footnote 12

Taken together, these results suggest that women may be particularly supportive of human rights treaties for a few reasons. First, because these treaties overlap with the domestic policy issues that women tend to pursue in their legislative work, women in the legislature may see these human rights treaties as a way to leverage similar, preferred domestic policies. Because of this, they may be more inclined to support human rights treaties specifically over other multilateral agreements. Additionally, because of women’s shared gendered experiences of violence, exclusion, and discrimination, they may be inclined to promote international human rights agreements aimed to protect similarly vulnerable populations on a global scale. These reasons might explain why women’s legislative presence is positively associated with the ratification of human rights agreements specifically.

Discussion and Conclusion

As more women enter legislatures around the world, the question of whether women’s inclusion in the legislative process leads to change in observed patterns of state behavior becomes more relevant. In this paper, we argue that women’s shared gendered experiences of exclusion, discrimination, and violence may inform their foreign policy preferences. Women may be more inclined to pursue foreign policy measures that prioritize marginalized and vulnerable groups because they share a sense of responsibility to similarly situated groups beyond their nation-state borders, acting as transnational surrogates on behalf of marginalized groups. Additionally, because women legislators tend to pursue policies that prioritize marginalized and vulnerable groups domestically, they may similarly advocate for foreign policy measures, like human rights treaties, that seek to achieve similar outcomes. Thus, we argue that as women’s legislative presence increases, this should lead to greater ratification of human rights treaties. In fact, we do find that countries with a greater presence of women in the legislature are more likely to ratify human rights treaties, indicating that women in domestic legislatures do have distinct foreign policy preferences for certain multilateral agreements. Specifically, our analysis of 201 multilateral agreements indicates that, in countries where legislative consent is required for treaty ratification, legislatures with a greater proportion of women are more likely to ratify human rights treaties.

With these findings, we contribute to the growing conversation of scholars who examine whether women legislators have distinct foreign policy preferences by highlighting the importance of women’s legislative presence on treaty ratification (Aggestam and True Reference Aggestam and True2020; Angevine Reference Angevine2017; Wilson Reference Wilson, Webster and Sell2014). These findings demonstrate that women’s legislative presence has an impact beyond their influence over domestic policy. Specifically, we show that women’s legislative presence has clear implications on foreign policy outcomes, whereby women are inclined to advocate for the protection and inclusion of vulnerable groups by promoting international treaties that protect human rights. In this way, we highlight that women legislators have distinct foreign policy preferences for certain types of international treaties, and because of these preferences, women’s presence in domestic legislatures has a direct impact on foreign policy outcomes.

Not only do women have distinct foreign policy preferences when it comes to international treaties, but our findings demonstrate that women have distinct foreign policy preferences on issues that are not overtly gendered (Betz, Fortunato, and O’Brien Reference Betz, Fortunato and O’Brien2023). Although previous research shows that women in domestic legislatures may have defined preferences for other foreign policy outcomes, such as defense spending, humanitarian aid, conflict behavior, and women’s rights treaties (Barnes and O’Brien Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Best, Shair-Rosenfield, and Wood Reference Best, Shair-Rosenfield and Wood2019; Koch and Fulton Reference Koch and Fulton2011; Shea and Christian Reference Shea and Christian2017; Stauffer et al. Reference Stauffer, Kobayashi, Martin-Morales, Lankes, Heinrich and Goodwinforthcoming; Woo and Ryu Reference Woo and Ryu2023), these are foreign policy outcomes that have a direct impact on the lives and well-being of women. Instead, we find that women’s foreign policy preferences extend beyond these more gendered policies. Women legislators are willing to advocate for foreign policy outcomes that benefit other vulnerable groups in addition to women by promoting the ratification of human rights treaties more broadly.

Additionally, this research contributes to the field of international cooperation by exploring, systematically, which factors drive certain states to ratify multilateral agreements. Multilateral treaties represent an important foreign policy tool used by states to coordinate policy responses to current and pressing global problems like global warming or future pandemics. Given their importance as a foreign policy tool, it is important to understand the domestic factors that contribute to the ratification of multilateral treaties to better understand patterns of which states are likely to engage in international cooperation. Here, we find that the presence of women in domestic legislatures explains patterns of human rights treaty ratification. Thus, this paper serves an important function by not only highlighting the distinct foreign policy preferences women have for human rights treaties but also highlighting how women’s presence in domestic legislatures is an important factor in explaining certain patterns of multilateral cooperation across states.

Our findings have important implications for practitioners as well. Human rights advocates who seek to promote the protection and inclusion of vulnerable populations can strategically target women legislators in their countries who may already be sympathetic to supporting human rights treaty measures. Additionally, there are practical implications that electing more women should result in more states signing onto human rights treaties. As women’s representation continues to increase globally, we should expect to see an increase in states that participate in international cooperation measures aimed at protecting the human rights of vulnerable groups. Whereas scholars debate the practical, humanitarian impact of international measures like human rights treaties, we highlight Simmons’s (Reference Simmons2009) findings that treaties can be effective when coupled with supporting domestic factors. Thus, increasing women’s representation may be a first step in realizing a tangible, humanitarian impact by electing domestic actors who are willing to ratify human rights treaties in the first place.

An important task for future research will be to investigate the mechanisms that drive the relationship between the presence of women in legislatures and the ratification of human rights treaties. These mechanisms may have consequences for domestic policies in countries that ratify these treaties. If women legislators are more likely to prioritize ratifying human rights agreements to leverage domestic policy changes, do these domestic policy changes occur upon treaty ratification? Put differently, is ratifying a human rights treaty an effective strategy for women to expand their preferred domestic policies? If the ratification of human rights treaties leads to a change in domestic policy patterns, this would suggest that women legislators are able to successfully advocate for the protection and inclusion of marginalized groups domestically while also advocating for these same groups on an international scale. Additionally, this might point to an effective, alternative way in which women are able to secure domestic policies that promote access to reproductive healthcare, wage equality, education, welfare programs, non-discrimination measures, and assistance programs, among others (Barnes Reference Barnes2012; Htun, Lacalle, and Micozzi Reference Htun, Lacalle and Micozzi2013; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2018). If this is the case, this may highlight that policy outcomes do not happen in a vacuum, potentially establishing an important link between foreign and domestic policy outcomes. This paper serves an important function in establishing the relationship between women’s legislative representation and the ratification of human rights treaties and paves the way for additional research that may provide a better understanding as to how women in domestic institutions formulate and develop foreign policy preferences, and how these foreign policy preferences may impact domestic policy measures.

Competing interest

The authors of this paper have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Leslie Schwindt-Bayer, Diana O’Brien, and Ashley Leeds who provided helpful feedback on this project. We are also grateful to the comments and suggestions of three anonymous reviewers at Politics and Gender who helped to improve this manuscript. We also thank the editor, Mona Lena Krook, for guidance throughout the editorial process.

Annex 1 Coding Rules

In the paper, we noted that our final dataset contains 201 agreements generated by expanding the data from Elsig et al. (Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011), which includes ratification information on 76 agreements open for ratification between 1990 and 2008. In addition to updating the ratification information of these agreements up through 2016, we expand the dataset to include agreements open to UN members for signature from 1945 to 1989. Below, we outline the specific criteria we used for the expansion of our data.

Candidate treaties for the expanded dataset are primarily generated from two sources: Lupu’s (2016) list of UN treaties and the websites of the constituent UN organizations. We began by leveraging and updating Lupu’s (2016) list of 280 agreements open for signature to UN members. We narrow our inclusion of these agreements into our dataset based on the following criteria. First, we exclude all agreements that were signed before the establishment of the UN. These agreements and their subsequent protocols were developed and approved in a manner inconsistent with developing an understanding of domestic ratification as they were technically ratified before the existence of the UN and simply reauthorized at a major international conference following World War II. Next, we eliminated agreements that were not open to accession by all members of the UN (e.g., European Agreement on Important International Combined Transport Lines and Related

Installations).

We include protocols to agreements under three conditions: 1) ratification of the original agreement does not automatically enter a state into protocol obligations, 2) the only barrier preventing a state from being eligible to ratify the protocol is ratification of the main agreement, and 3) all states are able to enter the original agreement.

Third, we eliminate documents that are not inherently new agreements such as publications of organization guidelines (Terms of Reference for the International Copper Study Group), revisions of texts (Revised text of Annex XII - International Maritime Organization), or amendments (Amendment to article 7 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization) that will go into effect for all members once certain conditions are met.

We compared our expanded list of treaties to the treaty lists available on the websites of the 14 specialized agencies of the UN (e.g., WIPO, ILO, and UNESCO). Although the data from Elsig et al. (Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011) captures treaties from these organizations well, these agreements largely fall outside the scope of Lupu’s (2016) data as they are not searchable on the UNTS. We include treaties created by these agencies that are open to all members of the UN for signature.

The authors gathered ratification information from the United Nations Treaty Series website for all remaining qualifying treaties that were not originally part of the Elsig et al. (Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011) data and merged it with their base data.

Annex 2 List of Agreements

Below is the list of human rights treaties used in our data.

Annex 3 Robustness Checks

Table 2. The effect of women’s representation on human rights treaty ratification (no legislative approval required)

Our main analyses are subset on the set of country-years where legislative ratification plays at least some formal role in the overall domestic ratification process. This is because our main theoretical argument rests on the idea that who sits in the legislature should matter for human rights treaty ratification. However, if the legislature has no role in the ratification process, then who sits in the legislature should not have a significant impact on the overall ratification process. Thus, we test our hypothesis on the set of country-years where the legislature does not have a formal role in the ratification process.

Although the percentage of women in parliament appears to be significant in the bivariate analysis, once we add in controls, the interaction between the percentage of women in parliament and human rights agreements is no longer statistically significant. These results logically align with the argument that the percentage of women in legislatures should only matter for human rights treaty ratification when the legislature has a formal role in the process. When the legislature plays no role in the ratification procedure, the percentage of women in the legislature has no relationship with human rights treaty ratification.

In Table 3, we examine the effect of women’s representation on the ratification of human rights treaties for countries that have enacted state-level legislative gender quotas vs. those who do not include quota mechanisms. Legislative gender quotas require all political parties to nominate a certain percentage of women candidates for national elections, usually resulting in a higher percentage of women elected to the national legislature. Not only are countries with gender quotas likely to elect more women to the legislature, but they may also be more progressive on social norms that promote women’s inclusion in politics, which may have led to the adoption of quota measures in the first place. Thus, to determine whether women’s representation has an independent effect on human rights treat ratification, it is important to test whether this relationship holds for countries that include quota measures as well as for those that do not.

Table 3. The effect of women’s representation on human rights treaty ratification (quota countries vs. non-quota countries)

Standard errors in parentheses

To do this, we subset our dataset into two groups: observations where a country has enacted a legislative gender quota and observations where a country has not adopted such a measure. We rerun the main model in Table 1 on both subsets. We find that, independent of whether women are elected through a gender quota, women’s representation still has a positive and significant effect on the ratification of human rights treaties. This analysis helps to further isolate the independent effect of women’s representation on human rights treaty ratification.

In Table 4, we compare the mean scores of our independent variables across countries that require legislative approval for ratification and those that do not require legislative approval. Overall, countries that require legislative ratification are fairly similar to those that do not require legislative ratification on the percentage of women in their legislatures, average human rights score, GDP levels, foreign aid received, etc. A slight difference emerges across the two subsets of countries on the average polity score, where countries that do not require legislative approval are slightly more autocratic when compared to countries that do require legislative approval. Substantively, however, this is not a large difference. For countries that do not require legislative approval for ratification, the average polity score falls slightly within the autocratic range while countries that do require legislative approval for ratification are anocratic, on average. Substantively, this is not a large difference in regime type across these two types of countries and, thus, we do not believe that there are any underlying differences across these subsets that are driving our results.

Table 4. Comparison of means: No ratification required vs. ratification required

In Table 5, we explore whether women’s legislative representation has a nonlinear effect on the ratification of human rights treaties. Woo and Ryu (Reference Woo and Ryu2023) find a nonlinear effect of women’s representation on the ratification of women’s rights treaties, indicating that as women’s legislative representation increases past a certain threshold, we may experience diminishing returns on the ratification of these types of treaties. To test this effect on the ratification of human rights treaties, we rerun our main models and include 1) a squared term for the lagged percentage of women in the legislature and 2) an interaction between the squared percentage of women in the legislature and whether the treaty is a human rights treaty. This will allow us to test for nonlinear effects.

Table 5. Nonlinear effect of women’s representation on human rights treaty ratification

Standard errors in parentheses

We do find a similar nonlinear relationship between the percentage of women in office and likelihood of human rights treaty ratification. This is indicated by the statistically significant, negative coefficient on the interaction between the percentage of women’s legislative presence squared and the human rights treaty indicator. This means that there might be a point at which adding more women legislators to a given parliament may reduce the likelihood of human rights treaty ratification. Put a different way, as women’s legislative representation continues to increase, there may be diminishing returns on the likelihood of human rights treaty ratification. This finding is similar to that of Woo and Ryu (Reference Woo and Ryu2023). However, one important caveat to consider is that in our sample, women’s representation in parliament is around 13%, on average with a standard deviation of 2.6% below the mean and 23.7% above the mean. Around 85% of treaty-country-years in our dataset feature less than 25% of women in their parliaments. Because women are underrepresented in the majority of state legislatures, we do not have a large number of observations of country-years at the higher end of this distribution, making it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the relationship that women’s representation has on treaty ratification for this higher range of women’s representation. Thus, we caution the interpretation of findings in this range.

In Table 6, we explore whether women’s legislative presence might have an effect on the ratification of other types of treaties. Specifically, we focus on environmental treaties. Based on suggestions from reviewers, we chose to examine the effect of women’s legislative representation on the ratification of environmental treaties. Women legislators might be inclined to support environmental treaties in the same way that they are supportive of human rights treaty ratification for a number of reasons (Atchison and Down 2019; Salamon 2023). Specifically, women tend to exhibit higher levels of concern about the environment, which may be because women tend to manage household resources that are more directly impacted by environmental changes, and women are more likely to be affected by natural disasters (Salamon 2023). For these reasons, we might expect women legislators to be similarly supportive of environmental treaty ratification.

Table 6. The effect of women’s representation on the ratification of environmental treaties

To conduct this analysis, we follow the coding scheme of Elsig, Milewicz, and Stürchler (Reference Elsig, Milewicz and Stürchler2011) and create a second category of environmental treaties in our dataset. We then subset our data to include only environmental treaties. These are treaties that deal with environmental issues on an international scale. For example, the Plant Genetic Resources Convention and the Meteorological Convention would be coded as environmental treaties. We do not find that women’s legislative presence has an effect on the ratification of environmental treaties. Women in the legislature may not necessarily be more inclined to support the ratification of these treaties. However, it is important to keep in mind the types of treaties that are coded as environmental treaties in our dataset. We may not see a significant support for the ratification of environmental treaties in our dataset because treaties like the Convention on the Continental Shelf may not have direct domestic policy implications for the lives of women or other vulnerable populations. Perhaps as environmental treaties change over time to include a greater number of treaties aimed at reducing the effects of climate change, addressing environmental disasters, and including explicit implications for domestic environmental policies, we may then see greater support for the ratification of these treaties among women in the legislature.

In Figure 3, we consider the symmetric marginal effect for treaty issue (whether a treaty is a human rights treaty or not) and treaty ratification condition on the level of women’s representation in the legislature. Following the procedures outlined in Hainmueller Mummolo and Xu (2019) to detect potential nonlinear effects, we utilize a binning strategy available in the interflex package in R to create low, medium, and high bins of the percentage of women in legislatures across our data. In the background is a histogram of the distribution of the percentage of women in legislatures in our dataset. Although it is less clear whether there may be nonlinear effects present at higher levels of women’s representation, for the levels of women’s representation that we observe in our data, the symmetric marginal effect is largely positive and linear. This result is largely in agreement with our main analysis and findings.

Figure 3. Robustness check: Marginal effect of human rights issue area on treaty ratification in varying levels of women in parliament.