Religion is often believed to contribute to a more dangerous and unstable world. Multiple studies demonstrate that conflicts involving religion are among the most severe and protracted (Abramson Reference Abramson2013). Prevalent explanations include that religions are “closed belief systems” whose moral values and symbolic goals demand stricter adherence than other identities (Seul Reference Seul1999; Thomas Reference Thomas and Dark2000), implying believers should view similarly exclusive claims by religious (or secular) others as threatening (Hassner Reference Hassner2011; Neuberg et al. Reference Neuberg2014; Brandt and Van Tongeren Reference Brandt and Van Tongeren2017). Believers may therefore also be less sensitive to the high material costs of dispute militarization, contributing to a greater propensity for conflict (Smidt Reference Smidt2005; Toft Reference Toft2006; Alexander Reference Alexander2017).

These intuitions are seemingly confirmed by research demonstrating that religiously-identified states more often engage in violent intrastate conflict (Pearce Reference Pearce2005), international crises (Fox and Sandal Reference Fox, Sandal and James2010; Özdamar and Akbaba Reference Özdamar and Akbaba2014), and cross-border military interventions on behalf of co-religionists (Fox Reference Fox2001; Gartzke and Gleditsch Reference Gartzke and Gleditsch2006). States with differently religiously-identified populations or leaders also fight one another more often (Henderson Reference Henderson1997; Ellingsen Reference Ellingsen2005; Lai Reference Lai2006). Conflicts between assertively religious and assertively secular states and between states with more religiously-committed populations are also more severe (Henne Reference Henne2012; Alexander Reference Alexander2017).

While intimating religion drives these conflicts, the relevant literature has largely neglected the foreign policy goals over which religious actors actually fight. For instance, are religiously-identified states more likely to militarize disputes over oil wells or sacred shrines? Despite broad agreement that issue salience is a key driver of dispute militarization (Diehl Reference Diehl2014), this discussion has garnered little attention regarding “religious” conflicts. Drawing from territorial conflict scholarship, where this topic has been most thoroughly explored, interstate disputes are more likely to turn violent when involving issues of high intangible salience, namely identity-related claims, than high tangible salience, over control of strategic or economic endowments (Hensel Reference Hensel and Vasquez2012). We hypothesize that religiously-exclusive states, states which intensively and exclusively support a single official religion, should behave similarly. With a mandate to “defend the faith” against internal and external challengers, religiously-exclusive states should pursue foreign policy goals which most directly signal commitments to these ideological ends. They should therefore strongly prefer to militarize territorial disputes over their intangibly-salient versus tangibly-salient attributes. They should also militarize such disputes more often than their secular counterparts.

This article tests these inferences through quantitative analysis of militarized interstate territorial disputes, or territorial militarize interstate territorial disputes (MIDs), in the post-Cold War era. We employ penalized maximum likelihood estimation, or Firth logit, models to gauge the impact of state religious exclusivity on year-level territorial MIDs, in monadic and dyadic variants. We confirm religiously-exclusive challenger states more often MIDs. Yet they are significantly more likely to do so owing to disputed territories' tangible rather than intangible salience. These tendencies may moreover be linked to increasing levels of democracy, rather than autocracy.

These findings highlight the surprisingly limited extent to which religiously-exclusive states allow ideological interests to dictate critical foreign policy decisions. By demonstrating their strong preference to militarize tangibly-salient disputes, we cast significant doubt on common assumptions that ideological prerogatives drive religious belligerence. The characterization of such conflicts as “religious” is accordingly misleading, and the much discussed international threat of religious violence may be substantially overstated. Our findings also have important implications for the probable effectiveness of deterrence and negotiation in diminishing these states' violent behavior. In light of these results, we recommend closer examination of how material and geopolitical conditions moderate religiously-exclusive states' foreign policy goals.

RELIGIOUS EXCLUSIVITY AND INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT

The past half-century has witnessed a “dramatic and worldwide increase in the political influence of religion” (Toft, Philpott, and Shah Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011, 9). While the implications of this trend for international peace and security are uncertain, dramatic events of the last half-century have generated substantial anxiety. From the Iranian Revolution, to the Sri Lankan civil war, to the 9/11 terror attacks and subsequent Global War on Terror, to the rise and ostensible fall of the Islamic State, perceptions that religion, and religious actors in particular, stoke international conflict are prevalent.

Multiple scholars have shown that conflicts involving religion are more severe and protracted. Identity-centered approaches demonstrate violence is more likely and intense between actors from different religious groups than those of the same faith, whether involving interstate or intrastate disputes (Henderson Reference Henderson1997; Ellingsen Reference Ellingsen2005; Pearce Reference Pearce2005; Lai Reference Lai2006). States also intervene more often in neighboring civil conflicts where minority co-religionists are present (Fox Reference Fox2004; Gartzke and Gleditsch Reference Gartzke and Gleditsch2006). Alternative approaches consider how states' religious policies moderate conflict behaviors. Conflicts between assertively religious and secular states, even of the same majority religion, are more violent and more protracted than other dyadic disputes (Henne Reference Henne2012), as are conflicts between dyads with more religiously-committed populations (Alexander Reference Alexander2017). States which exclusively support a single religion (Fox and Sandal Reference Fox, Sandal and James2010) or otherwise discriminate against religious minorities (Özdamar and Akbaba Reference Özdamar and Akbaba2014) are also more likely to become embroiled in international crises. These results hold even controlling for level of democracy.

Proponents of both methods share the theoretical proposition that religions are strict, inflexible ideologies which provide believers with a sense of collective belonging while demanding compliance with set attitudinal and behavioral norms (Seul Reference Seul1999). To the extent religion defines “absolute” and “universal” truths, encounters with those who do not share these truths can engender discord (Thomas Reference Thomas and Dark2000; Neuberg et al. Reference Neuberg2014; Brandt and Van Tongeren Reference Brandt and Van Tongeren2017). Belief in these religious truths and the necessity of their pursuit can further condition policymakers and publics alike to be more accepting of conflict's high material costs (Smidt Reference Smidt2005; Toft Reference Toft2006; Alexander Reference Alexander2017).

These propositions should be particularly true regarding religiously-exclusive states, defined as states which intensively and exclusively support a single official religion. Positively, this includes whether states enshrine a given religion as their official faith and substantially control its institutions. Unlike states with established religions, under which Great Britain and Saudi Arabia are equivalent, religiously-exclusive states claim a mandate to “defend the faith”. Negatively, this includes high levels of discrimination against minority religions. Accomplishing “little other than hampering the viability of religions other than the majority religion,” doing so indicates a desire to achieve or defend a “religious monopoly” (Fox Reference Fox2015, 138). Religiously-exclusive states should therefore be particularly prone to interstate belligerence as institutionalized intolerance should reduce willingness to compromise with ideological opponents. The substantial extent to which religion has been politicized therein also suggests leaders bear high costs for such compromises, both regarding popular credibility and in providing domestic rivals opportunities to contest their legitimacy.

Yet even as available data suggests religiously-exclusive states are particularly belligerent, they often engage in substantial cooperation and compromise even with religiously-exclusive rivals (Appleby Reference Appleby2000; Hasenclever and De Juan Reference Hasenclever and De Juan2007; Robbins and Rubin Reference Robbins and Rubin2017). As Shaffer (Reference Shaffer2006, 4) shows regarding three self-proclaimed Islamic Republics: Iran, Pakistan, and Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, “even the most culturally and ideologically articulate states in the international system […] can conduct [foreign] policies on a regular basis that completely contradict their formal cultural identification, dictates, and consequent state ideology—without domestic retribution.” Indeed, despite post-revolutionary Shi'ite Iran's proxy and direct violent conflicts with Ba'athist, Sunni-dominated Iraq, its concurrent relations with Orthodox-Christian Armenia (with its own violent history with Shi'ite Azerbaijan) were amiable. It follows that neither mutual religious intolerance nor assumed domestic blowback for religiously-transgressive diplomacy can reliably predict interstate belligerence.

These problematic assumptions may stem from a particular lacuna in the study of religion and conflict. While most conflict scholars agree “issues, their salience, and the nature of the stakes that constitute them, and the manner in which these stakes are linked” are key to understanding conflict (Mansbach and Vasquez Reference Mansbach and Vasquez1981, 73; Diehl Reference Diehl2014), literature on religious conflict has largely overlooked the issues over which religiously-identified states actually fight. By emphasizing religious identities and state-religion policies to the exclusion of foreign policy disputes themselves, existing scholarship has difficulty accounting for behaviors like those documented by Shaffer (Reference Shaffer2006). For instance, perhaps Iran and Armenia maintain close diplomatic relations precisely because their greatest reciprocal concern is cross-border trade rather than diaspora co-religionists. Identifying which issues most compel religiously-exclusive states' belligerence is therefore essential to determining whether and how religion influences these outcomes.

ISSUE INDIVISIBILITY AND POLICY OUTBIDDING IN TERRITORIAL DISPUTES

To accomplish this, we turn to the international territorial conflict literature wherein issue salience has been most thoroughly addressed (Diehl Reference Diehl2014). There researchers distinguish between tangibly- and intangibly-salient issues—whether disputed territories are coveted for their strategic or economic endowments versus their contributions to collective identity (Hensel Reference Hensel and Vasquez2012). Although states often engage in intense conflict over tangibly-salient resources (Carter Reference Carter2010; Sorens Reference Sorens2011), intangibly-salient disputes appear prone to greater militarization at the interstate and intrastate level (Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005; Shelef Reference Shelef2016; Kelle Reference Kelle2017). This is presumably because identity-based claims are more indivisible than strategic or economic claims (Tir Reference Tir2003; Johnson and Toft Reference Johnson and Toft2014) and territorial conflict itself increases identity politics' resonance (Gibler, Hutchison, and Miller Reference Gibler, Hutchison and Miller2012; Tir and Singh Reference Tir and Singh2015).

Facing competing claims to territories integral to the national homeland or populated by kin groups, these nationalist prerogatives are often elevated from strategic goods or political interests to matters of existential necessity (Shelef Reference Shelef2016). Such emotional resonance is rare over spaces of “mere” economic or strategic value, and the political costs of failing to defend them typically pale in comparison. While the capture of tangibly-salient territories provides concentrated gains to elites and security-sector actors, positive externalities are typically too diffuse to be felt by the average citizen. By contrast, domestic audiences respond to intangibly-salient claims precisely because publics are invested in the symbolic functions these spaces represent (Tir Reference Tir2003; Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005; Wright and Diehl Reference Wright and Diehl2016). Leaders recognize identity-based claims' greater affect and often foist these frames upon “merely” tangibly-salient disputes. However, these efforts have limited returns where such framings are not already deeply familiar to targeted audiences (Desrosiers Reference Desrosiers2012; Zellman Reference Zellman2015). Leaders therefore do not enjoy an unrestricted license to characterize oil fields as holy sites.

Preferences to militarize intangibly-salient over tangibly-salient territorial disputes are especially pronounced among states which exclusively serve a given identity group (Yiftachel and Ghanem Reference Yiftachel and Ghanem2004; Moore Reference Moore2016; Barak Reference Barak2017). Even as leaders of these states actively advance identity claims in the domestic sphere, their very politicization renders ruling parties vulnerable to challenge when they falter in their defense. Intangibly-salient disputes therefore pose particular risks as they enable domestic litmus tests of leaders' ideological commitments. When domestic rivals question rulers' commitments to these spaces, leaders are compelled to “outbid” these challenges, adopting more extreme policy agendas and political discourses, further raising costs of compromise (Goddard Reference Goddard2010; Wright and Diehl Reference Wright and Diehl2016). In doing so, the locus of popular political power shifts from the median to more nationalist constituencies, making leaders more dependent upon their support and rendering militarization of otherwise negotiable international disputes more likely (Kertzer and Brutger Reference Kertzer and Brutger2016; Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017; Zellman Reference Zellman2019). Intangibly-salient dispute militarization therefore becomes more likely because constituents of identity-exclusive leaders believe them to be more important and failure to press extreme claims to these spaces increased their vulnerability to domestic challengers.

There are good reasons to expect religiously-exclusive states to replicate these patterns. If secular states tend to prioritize ethnic and/or nationalist concern for cross-border kin and lost homelands, so should religiously-exclusive states benefit from advancing mirrored concerns for cross-border co-religionists, sacred sites, and holy lands (Oommen Reference Oommen1994; Sandler Reference Sandler2017). As states whose explicit mandate is to “defend the faith” against domestic and foreign challengers, constituent publics should be more readily mobilized by threats to religiously-valued spaces than those of “mere” material or strategic interest. If religious prerogatives are indeed more absolute and inflexible than secular-nationalist ones, so too should religiously-exclusive states be more resistant to compromise over these spaces.

Religiously-exclusive states' deep investments in ideological prerogatives should further generate strong political incentives for domestic rivals to contest leaders' political and religious legitimacy when they are perceived as failing to defend them (Hasenclever and De Juan Reference Hasenclever and De Juan2007; Toft Reference Toft2013; Basedau, Pfeiffer, and Vüllers Reference Basedau, Pfeiffer and Vüllers2016; Isaacs Reference Isaacs2017). This is especially true during domestic political crises, themselves often precipitated by external territorial threats (Carment and James Reference Carment and James1995; Tir Reference Tir2010). Indeed, scholars of religion and politics have widely observed a politics of “religious outbidding” where embattled rulers respond to challenges not only by limiting same-religion challengers' political autonomy (e.g., Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt) but by doubling down on restrictions on religious minorities to signal their commitments to the dominant religion (Finke, Martin, and Fox Reference Finke, Martin and Fox2017).

We therefore predict religious outbidding should have similar downstream consequences for dispute militarization as observed for outbidding elsewhere. That is to say, because religiously-exclusive states invest significant domestic resources in “defending the faith,” these regimes should have the most to gain and lose politically in militarizing intangibly-salient versus tangibly-salient territorial disputes. While the pursuit of intangibly-salient claims should directly appeal to constituent publics as evidence of the state's religious commitments, leaders should especially fear backing down from these claims for their potential to strengthen domestic challengers. These processes limit politically-acceptable bargaining outcomes for religiously-exclusive states, rendering dispute militarization a perversely attractive policy option. Religiously-exclusive states should therefore not only prefer militarization of intangibly-salient over tangibly-salient issues, but religious outbidding dynamics should exercise a multiplicative effect whereby these tendencies are more pronounced among religiously-exclusive than secular states. We formalize these propositions below:

H1: Religiously-exclusive states are more likely to MIDs owing to their intangible rather than tangible salience.

H2: Religiously-exclusive states are more likely than non-religiously-exclusive states to militarize territorial disputes owing to their intangible salience.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Data and Dependent Variables

We test these hypotheses using the recently-expanded Issue Correlates of War (ICOW) dataset, which encompasses global dyadic territorial claims from 1816 to 2001 (Frederick, Hensel, and Macaulay Reference Frederick, Hensel and Macaulay2017), with dispute militarization data from the Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) dataset (Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, d'Orazio, Kenwick and Lane2015). Religion variables are derived from the Religion and State Project, round 3 (RAS3) (Fox Reference Fox2015), which codes state-religion policies and practices for all states with a population of at least 250,000, from 1990 to 2014.

Due to the respective datasets' different time frames, analysis is constrained to territorial claims from 1990 to 2001. Given the scarcity of worldwide, country-level data on state-religion policies, most quantitative studies on religion and conflict are under similar temporal constraints. We however demonstrate, via fully-interacted logistical models in Appendix I, that average effects of relevant variables for our period of study, excluding religious indicators, are similar to previous historical eras surveyed by ICOW. This does not guarantee external validity prior to the post-Cold War era. It does suggest if states engaged in comparable patterns of religious policymaking in the past as the present, they would exercise broadly similar foreign policy influences.

Our dependent variable, midissyr, dichotomously measures whether a MID occurred between each politically-relevant dyad in each of the 11 years under study. Our data includes 1,414 politically-relevant territorial claim-year dyads, 101 of which include a claim-year MID (or 126 politically-relevant territorial claim dyads encompassing 39 distinct MIDs). The proportion of MIDs to total dyads is low at 7.14%, but defensible. Indeed, Hensel and Mitchell's (Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005) initial data, covering only territorial claims in the Americas and Western Europe, was widely utilized by conflict researchers despite MIDs therein representing only 305 of 10,041 or 3.04% of politically-relevant claim-year dyads.Footnote 1

Explanatory and Control Variables

Our primary explanatory variables are drawn from ICOW and RAS3. Tangible salience (saltan) is additively measured according to whether claimed territory contains potentially valuable resources, is strategically located, and is populated. Because ICOW assumes tangible salience is intrinsic to territory regardless of the claimant, the base tangible salience score for each dyad is doubled. Territories fulfilling all three conditions receive a score of 6. Although often overlapping with intangible concerns, common examples of high tangibly-salient territories include the Falkland Islands/Las Malvinas and the Golan Heights.

ICOW's intangible salience index (salint) includes a three-point scale for challenger and target states for whether each consider disputed territories part of the national homeland rather than “colonies” or “dependencies,” have “ethnic, religious, or other identity ties to the territor[ies] and [their] residents,” and have previously exercised sovereignty therein (Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005, 278). High intangibly-salient territories thus include Arunachal Pradesh, Jerusalem, and Northern Cyprus. We however primarily employ ICOW's dummy for challenger and target identity claims, tcidenchal and tcidentgt, as a more conservative measure. Identity ties may not be religious, but close correlations typically exist between religious and other identities. This approach therefore excludes more political aspects of intangible salience as commonly measured, which are less relevant to the present analysis. Robustness checks confirm this substitution has no substantial influence on findings.

The first aspect of our measure for state religious exclusivity is RAS3's religious discrimination index (mxx). This variable is compiled from the additive measure of 36 distinct forms of discrimination placed by states on the religious institutions or practices of minority religious groups not enforced upon the majority religion.Footnote 2 We differentiate between religious discrimination by challenger and target states as chal_mxx and tgt_mxx. In models considering interactive effects with religious discrimination, we utilize dichotomous terms for challenger and target states, as chal_mxx_q4 and tgt_mxx_q4. These variables assign a value of 1 to the upper quartile of religiously-exclusive challenger and target states (mxx > 35 and mxx > 25) and 0 to the remaining lower quartiles. Although the two highest scoring states on this index, Iran and Saudi Arabia, are theocratic, religious discrimination is not reducible to states' autocratic tendencies. As demonstrated below, our models even suggest religious discriminators are more conflict-prone as they become more democratic.

Although states which score high on mxx are typically more religiously exclusive, some such as China and Cuba have little ideological investment in religion. To more precisely capture our concern with “defenders of the faith,” we therefore interact mxx with a dummy indicating whether challenger and target states positively support an official religion and substantially control its institutions as chal_stconrel and tgt_stconrel. This dichotomous indicator is derived from RAS3's sbx, a 14-level ordinal variable, coded from 0 to 13, measuring each state's relationship to religion ranging from outright hostility (0) to maintaining a state religion, in which membership is mandatory for all citizens. The stconrel variables take a value of 1 if the state receives a score of at least 11 in sbx and 0 otherwise.

Challenger states' distribution along these two metrics is illustrated in Figure 1. Of 93 unique challenger states in 1,414 year-level claim dyads, 72 states neither exercise positive control of an official religion nor are among the upper quartile of religious discriminators. Nine states representing 103 year-level claim dyads exercise substantial control of an official religion and are in the upper quartile of religious discriminators. Nine states engaged in 246 year-level claim dyads are high religious discriminators but do not control a state religion, while seven states engaged in 113 year-level claim dyads control state religions but are not high religious discriminators.Footnote 3 While religiously-exclusive states constitute a minority of cases, they are numerous and diverse enough to alleviate the concern that epiphenomenal attributes of these states rather than religious exclusivity drive results.

Figure 1. Distribution of challenger states by religious-regime characteristics

Our first set of control variables are drawn from RAS3. These include two additive indices: lxx, measuring 52 distinct policies by which states publicly support religious groups and practices regardless of majority versus minority status and nxx, measuring 29 distinct forms of state regulation on the expression and public performance of all religions. We also differentiate in these indices between challenger and target states as chal_lxx, chal_nxx, tgt_lxx, and tgt_nxx. Although lxx indicates a positive official orientation toward religion, its non-discriminatory application renders it inappropriate to gauge state religious exclusivity. In turn, nxx suggests a negative state orientation toward religion regardless of its practice by majorities or minorities and is therefore also inappropriate to measure religious exclusivity. These variables' inclusion is essential however as they capture distinct measures of religious policy which could conceivably moderate dispute militarization. In additional robustness checks on our dyadic models, we also include measures of same versus different religious-majority dyads, none of which significantly influence dispute militarization.

We also include several control variables common to the territorial conflict literature. The first measures relative power disparity (preponderance) between challenger and target states, expecting that states with substantially uneven capabilities should be less likely to fight one another. For this, we use the “Composite Index of National Capability” (CINC) score, measuring each country's relative share of the world's industrial, demographic, and military capabilities (Singer, Bremer, and Stuckey Reference Singer, Bremer, Stuckey and Russett1972). For dyadic disparity, we use Hensel and Mitchell's method (Reference Hensel and Mitchell2005, 279), as the percentage of the total dyadic capabilities held by the stronger side, varying from 0.5 to 1.0. In monadic models, we employ ln_chal_cinc, the natural logarithm of challenger states' CINC scores. This follows Quackenbush and Rudy (Reference Quackenbush and Rudy2009) who argue this transformation captures the declining marginal effects of increasing state power. We also control for joint democracy of conflict dyads (jointdem), when both states score 6 or higher on the PolityIV democracy scale (Marshall and Jaggers Reference Marshall and Jaggers2009). In each monadic model and those dyadic models involving interaction terms, we employ separate measures for the challenger and target PolityIV scores as chal_polity and tgt_polity.

We include three further controls, often negatively associated with territorial conflict, in dyadic models. Alliance measures the extent to which each dyad belongs to a similar constellation of military alliances (Gibler and Sarkees Reference Gibler and Sarkees2004); trade measures trade reciprocity as the sum of imports within each dyad (Barbieri, Keshk, and Pollins Reference Barbieri, Keshk and Pollins2009); and IGO measures joint membership in international organizations (Kinsella and Russett Reference Kinsella and Russett2002).Footnote 4 Many studies of territorial conflict also include a distance measure, as most territorial conflicts occur between contiguous states such that increasing distance should decrease MID occurrence (Stinnett et al. Reference Stinnett2002). We exclude this as it introduces significant multicollinearity in all models. Robustness checks however confirm its inclusion has no effect on key variables.

Methods

We employ penalized maximum likelihood estimates, or Firth logits, a highly effective method to reduce bias in the analysis of rare events, especially in small samples (Firth Reference Firth1993). Because MIDs in the post-Cold War period represent a small portion of political-relevant dyads with a territorial claim, this renders maximum likelihood estimators like conventional logistical regressions inappropriate. A somewhat more common approach in international relations scholarship is to use King and Zeng's (Reference King and Zeng2001) “rare event logistic regression” or relogit. However, relogit generally over-corrects maximum likelihood estimations as sample size decreases, whereas Firth logits remain considerably unbiased (Heinze and Schemper Reference Heinze and Schemper2002; Leitgöb Reference Leitgöb2013).

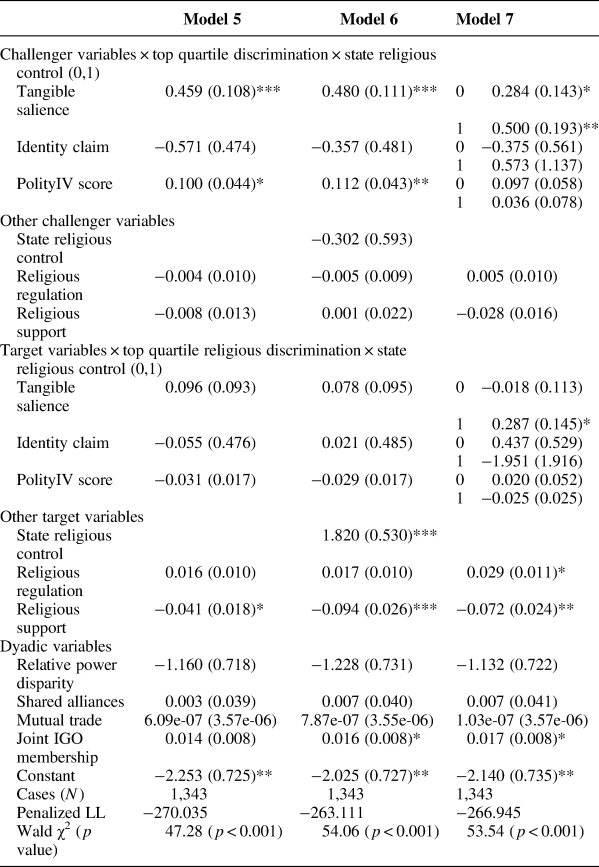

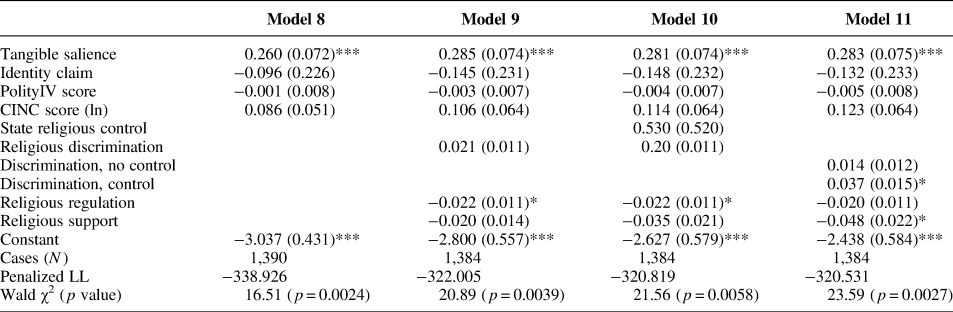

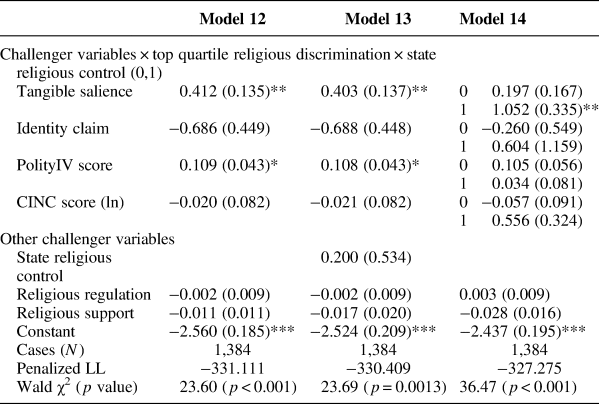

Our first set of models examine dyadic relationships between challenger and target states engaged in international territorial disputes. Model 1 offers a baseline analysis of year-level territorial MIDs employing ICOW's tangible salience and identity claim indicators and previously mentioned controls for the post-Cold War period. Model 2 adds RAS3's primary indices for state-religion policy by challenger and target states and model 3 includes our dummy for state religious control. Finally, model 4 employs a factorial interaction between religious discrimination and state religious control to differentiate between merely discriminatory and religiously-exclusive states. Model 5 substitutes index measures for the challenger and target religious discrimination for dichotomous variables identifying states in the most religiously-exclusive quartile of challenger and target states. These are interacted with tangible salience and identity claims for challenger and target states as well as each state's PolityIV score. Models 6 and 7 include state religious control, with factorial interactions to isolate the extent to which religious exclusivity drives territorial target preference and whether religiously-exclusive states' belligerence is driven by regime type. Our second set of models monadically examine conflict militarization by challenger states, with models 8–11 paralleling models 1–4 and models 12–14 paralleling models 5–7. Monadic analyses largely confirm dyadic findings.

Alternative models offering various robustness checks are offered in Appendix I. These include substitution of intangible salience for identity claims, effects for same versus different religion dyads, exclusion of the potentially problematic IGO variable, inclusion of the problematic distance variable, and fully-interacted models to confirm the statistical similarity of ICOW data on relevant variables between the post-Cold War period and its full time range.

FINDINGS

Our models confirm that religiously-exclusive states are more likely to militarize interstate disputes, however they do so owing to territories' tangible rather than identity salience. We also find religiously-discriminatory states are more likely to militarize said disputes as they become more rather than less democratic, but this effect does not necessarily hold for religiously-exclusive states. In all, our findings raise significant questions regarding the issue motivations of religiously-exclusive states' foreign policies. We explore these findings in detail as they relate to each of our 14 models. All dyadic models are highly significant via Wald χ2 tests with at least 99.9% confidence, and all monadic models are significant with at least 99% confidence. Detailed findings for dyadic and dyadic-interacted models are found in Tables 1 and 2 and monadic and monadic-interacted models in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 1. Religious exclusivity and militarized interstate territorial disputes, 1990–2001, Firth logistical regressions, dyadic models 1–4

Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Table 2. Dyadic models 5–7

Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Table 3. Monadic models 8–11

Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Table 4. Monadic models 12–14

Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Model 1, based upon ICOW data in the post-Cold War era, demonstrates that both tangible salience and target state identity claims are significant predictors for territorial MIDs. Challenger states are however significantly less likely to militarize territorial disputes in which they have identity claims. This somewhat confusingly suggests challenger states tend to militarize disputes in which their targets have identity claims but in which challengers themselves do not. A more careful look reveals that every territory to which target states have identity claims is also tangibly salient, suggesting this finding may be an artifact of challenger states' preferences to militarize tangibly-salient disputes.Footnote 5 In turn, no single control variable is significant. The absence of significant effects for alliance composition and trade reciprocity is consistent with ICOW's full date range, although capability disparity and joint democracy are significantly negatively associated and joint membership in IGOs is significantly positively associated with conflict in the full time range, respectively. These findings are paralleled by our monadic examination in model 8. Their identity claims are insignificant predictors of dispute militarization. Although differing from the same model run on ICOW's full date range, this finding raises the same cautionary flags discussed above regarding the dyadic model.

Model 2 includes RAS3's measures for minority religious discrimination (mxx), religious regulation (nxx), and religious support (lxx). This model replicates model 1 with tangible salience and target identity claims significantly positively associated with territorial MIDs and challenger identity claims negatively so. In turn, challenger state religious discrimination has a significant positive effect while target state religious support has a negative one. These results are largely mirrored in monadic model 9, wherein tangible salience remains highly positively significant, however identity claims are not. Here, challenger state religious discrimination is nearly significant (p = 0.056), while religious regulation is negatively correlated with dispute militarization.

Model 3 introduces challenger and target state religious control (stconrel) to determine if minority religious discrimination and state religious control distinctly influence dispute militarization. Findings again closely replicate the previous model insofar as tangible salience and target state identity claims remain significantly associated with dispute militarization and challenger state identity claims negatively so. Challenger state religious discrimination and target state religious support also remain positively and negatively significant, respectively. This model also reveals that target state religious control significantly predicts dispute militarization. Monadic model 10 produces similar results with tangible salience highly significant, religious discrimination nearly significant (p = 0.066), and religious regulation having a negative significant influence.

Finally, model 4 confirms tangible salience and target identity claims' significant positive and challenger identity claims' significant negative effects. More important, it directly demonstrates religiously-exclusive states' conflict proneness, with both challenger and target state religious exclusivity, that is increasing religious discrimination in the framework of state control of religion, being significantly associated with dispute militarization. Challenger states religious discrimination lacking state religious control is however also nearly significant (p = 0.053). These findings suggest a greater potential for conflict between religiously-exclusive dyads. Monadic model 11 substantially replicates these results with significance for both tangible salience and the religious exclusivity interaction term.

To more directly evaluate our hypotheses, that religiously-exclusive states MIDs owing to their intangible rather than tangible attributes (H1) and do so with greater regularity than non-religiously-exclusive states (H2), we present several interacted dyadic and monadic models in Tables 2 and 4. These consider how the top quartile of religiously-discriminatory states differ from the bottom three quartiles regarding territorial dispute militarization and how these patterns change when accounting for state religious control. They simultaneously examine the extent to which religiously-exclusive states' disproportionate conflict-proneness is driven by authoritarian rather than religious predilections.

Dyadic model 5 finds tangible salience significantly predicts dispute militarization for highly discriminatory challenger states as do increasing levels of democracy, while no such significant effects are observed for target states. Monadic model 12 replicates these findings on tangible salience and increasing democracy. Dyadic model 6, which includes state religious control, returns similar results with tangible salience and increasing democracy both significantly associated with dispute militarization for highly discriminatory challenger states. Target state religious control also significantly predicts dispute militarization. Monadic model 13 confirms these findings with tangible salience and increasing democracy significantly correlated with dispute militarization.

Finally, dyadic model 7 offers the most direct evidence to test our hypotheses regarding religiously-exclusive states by differentiating between mere high religious discriminators and those states which also substantially control their official religion, claiming a mandate to “defend the faith.” Here we find that for challenger states, both religious exclusivity and religious discrimination alone significantly predict militarization of tangibly-salient disputes, although the former an order of magnitude higher than the latter. So too, religiously-exclusive target states are more likely to militarize tangibly-salient disputes. Recalling model 4, these results not only suggest religiously-exclusive states are more likely to fight one another, but also they are more likely to do so over tangibly-salient rather than identity claims! Findings regarding tangible salience are replicated for religiously-exclusive challengers although not discriminatory ones in monadic model 14. In these models, increasing democracy is insignificant for both religiously-exclusive and highly-discriminatory states. While this diminished significance may result from splitting an already small number of cases, that no such effects appear for tangible salience counsels cautious interpretation for religiously-exclusive states.

IMPLICATIONS

These findings make an important contribution to the study of religion and conflict. While confirming religiously-exclusive states are more conflict-prone especially in matched dyads, our models raise serious questions regarding the extent to which “religion” drives this belligerence. That religiously-exclusive challenger states are no more likely to militarize identity claims than more secular states, even versus religiously-exclusive target states, disconfirms common assumptions that religious actors' ideological intolerance or political beholdenness to religious ideologies necessarily render them less compromising over identity claims.

More remarkable is that both religiously-exclusive challenger and target states are more likely to invest coercive force into advancing material or strategic claims to disputed territory than identity claims. This may owe to the identity claim variable's non-specific consideration of religious claims. For instance, religiously-exclusive states may have little interest in defending ethnic kin who do not share their faith or in revanchist claims to territories whose popular value is rooted in secular nationalist rather than religious narratives. It may also reflect this study's brief time span, which may not include sufficient instances of dispute militarization to effectively capture hypothesized trends. However, such data limitations cannot explain why religiously-exclusive states so strongly prefer militarization of tangibly-salient disputes, which have no intrinsic identity relevance and for which they should face far fewer domestic repercussions for backing down.

Our findings rather suggest that religiously-exclusive states are uncommonly capable of coping with foreign policy outbidding traps theorized to drive the militarization and protraction of intangibly-salient disputes (Goddard Reference Goddard2010). This despite the considerable extent to which the ideological character of these regimes incentivizes domestic policy outbidding over religious issues (Toft Reference Toft2013; Basedau, Pfeiffer, and Vüllers Reference Basedau, Pfeiffer and Vüllers2016; Isaacs Reference Isaacs2017), religiously-exclusive states' tendency to disproportionately militarize tangibly-salient territorial disputes, whose value is typically less apparent to domestic publics, thus represents a direct inversion of expected foreign policy behavior. Indeed, Wright and Diehl (Reference Wright and Diehl2016) propose that preferences to fight for tangibly-salient territory should be most common among more authoritarian regimes, whose relevant constituencies are narrower and more likely to directly benefit from resources extracted from such spaces. Regarding religiously discriminatory states, we find precisely the opposite: that they increase in belligerence as they become more democratic, focusing coercive energies on material rather than ideological objectives. Readers should however be cautious in applying this conclusion to religiously-exclusive states based upon present data.

We speculate that the very domestic policies by which religiously-exclusive states signal their commitments to “defend the faith” afford them flexibility in pursuing non-ideological foreign policy goals. By investing tremendous political capital in identity-based domestic policy commitments to the dominant religion, leaders may more credibly compromise on parallel religious prerogatives abroad, while pursuing strategic interests likely to bolster the military or economic strength of the regime. In this manner, religiously-exclusive state leaders could plausibly reinforce their domestic approval and consequent electoral prospects, while engaging in precisely those foreign military pursuits publics are often theorized to reject (e.g., Gartner Reference Gartner2008; Debs and Goemans Reference Debs and Goemans2010; Valentino, Huth, and Croco Reference Valentino, Huth and Croco2010). This may include close cooperation with “enemy” religious others and concessions on religiously-salient foreign policy goals.

One key example is Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states' increasingly open diplomatic, economic, and security cooperation with Israel (Beck Reference Beck2015; Rabi and Mueller Reference Rabi and Mueller2017). While directed against Iran, these burgeoning relations are remarkable in that they come at the expense of support for Palestinian self-determination, a once vehement condition for any such diplomatic opening. Another is Armenia's cordial relations with GA, reinforced by Armenia's explicit refusal to recognize the autonomy or independence demands of Armenians in GA's Javakheti region (Ter-Matevosyan and Currie Reference Ter-Matevosyan and Currie2019). Despite Armenia's highly religiously-exclusive commitments to the Armenian Apostolic Church, it has remained mum both on settlement efforts by GA to change the demographic balance in Javakheti to favor ethnic Georgians and “seizures” of historic Armenian churches by Georgian Orthodox Church clergy (Blauvelt and Berglund Reference Blauvelt, Berglund, Siekierski and Troebst2016).

Although similar in temporal constraints to most studies of religion and conflict, this research is based upon more truncated data than typically employed regarding the international territorial conflict. Our speculative framework does however provide a compelling explanation for its counterintuitive results wherein religiously-exclusive states defer militarizing identity claims in favor of tangibly-salient disputes. Rather than deny ideological exclusivity influences conflict, we suggest religiously-exclusive states are able to prioritize strategic and economic foreign policy pursuits precisely because of the ideological credibility they cultivate as domestic “defenders of the faith.” While this relegates religious-exclusivity to a more indirect role in conflict promotion, it suggests key mechanisms by which religious-exclusivity should have an effect. These include engaging in religious outbidding on domestic issues to pacify relevant constituencies, thus limiting the capacity of domestic challengers to outbid rulers on ideological foreign policy commitments. To better test these inferences, further data collection is warranted, including expanding existing measures of state religious-exclusivity to include a broader time range as well as explicit coding of religious territorial salience to supplement existing salience measures.

Our results also provide insight into popular debates regarding dangers posed by religious violence on the international stage. While confirming religiously-exclusive states are more belligerent, that this belligerence is directed toward tangibly-salient foreign policy goals rather than identity claims suggests a reduced threat. Even if ideological exclusivity or intolerance of otherness broadly motivates domestic policy-making, this does not necessarily translate to the militarization of identity claims. This diminished propensity to clash over issues commonly assumed most indivisible and therefore most intractable suggests the surprisingly limited extent to which religiously-exclusive states allow ideological prerogatives to dictate critical foreign policy decisions.

Instead, religiously-exclusive states' evince clear preferences to militarize territorial disputes which are most divisible and materially substitutable. This further implies they should be more responsive to negotiated compromise and deterrence strategies which increase the material costs of conquest than their oft-assumed “fundamentalist” ideologies would suggest. While our results do not deny religious exclusivity's potential threats to international peace, they suggest they are less menacing and more nuanced than commonly assumed.

CONCLUSIONS

Religion and conflict scholars often argue that religious political actors' belligerence on the world stage owes to their disproportionate ideological commitments. More religiously-exclusive states therefore engage in greater levels of dispute militarization not only because they are intolerant, but because their investments in domestic religious legitimacy open them to greater criticism should they compromise on these values abroad. These dynamics should also lead religiously-exclusive states to prioritize identity claims over tangibly-salient foreign policy goals, as the former are more relevant to religious symbolic prerogatives and more likely to resonate with these regimes' constituent publics.

We test these inferences via global quantitative analysis of territorial MIDs in the post-Cold War era, examining a variety of critical geopolitical conditions, regime characteristics, state-religion policies, and disputed territories' salience to claimants. Our results directly contradict these theoretical hunches, finding that religiously-exclusive states significantly prefer to militarize tangibly-salient disputes over identity claims, perhaps even as they become more democratic. We propose a novel explanation: that religiously-exclusive states' deep commitments to defending domestic ideological prerogatives inoculate them against foreign policy outbidding, elsewhere theorized to drive the militarization of identity-salient disputes, especially among more democratic states. This argument finds support in several significant cases.

Our results moreover speak encouragingly to the threats to international peace and security posed by religious violence. Finding that religiously-exclusive states tend to fight over strategic material rather than ideological interests suggests a more limited threat. Given tangibly-salient policy goals' greater divisibility and substitutability, it further appears religiously-exclusive states should be more amenable to conflict resolution than commonly assumed. We therefore join a host of scholars who argue against popular approaches which uncritically view religious actors as fanatical or irrational and thus unresponsive to deterrence or negotiation.

This article's findings should be of interest to policy practitioners and scholars alike. To the former, it counsels reduced anxiety over religion's increasing influence in the international political sphere, recommending closer attention be paid to the domestic political instruments by which religious actors are encouraged to initiate interstate violent conflict. To the latter, it raises serious questions over common assumptions regarding religion's influence on international conflict processes and proposes new avenues for research, data collection, and potential case applications to test its speculative inferences. While far from denying religious exclusivity's role in sustaining political and social intolerance, we urge renewed emphasis upon the material interests and geopolitical conditions under which religious actors operate.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048319000488.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Funding for data collection on the Religion and State Project, round 3 (PI Prof. Jonathan Fox) was generously provided by the Israel Science Foundation, grant 23/14, and the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development, grant I-1291-119.4/2015.