Introduction

Pharmacy health service research is rare compared with other health services. Community pharmacies are an under-utilized resource (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Ferguson, Barton, Maskrey, Blyth, Paudyal, Bond, Holland, Porteous, Sach, Wright and Fielding2015). In the United Kingdom, most community pharmacies are owned by large chains such as Lloyds Pharmacy, Boots the Chemist and Moss Pharmacy. Community pharmacists see over 90% of the population/year (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). About 99% of UK’s population can get to a pharmacy within 20 min and in the areas of highest social deprivation, this increases to almost 100%, due to positive pharmacy care law (Eaton, Reference Eaton2008; Todd et al., Reference Todd, Copeland, Husband, Kasim and Bambra2015). In the most affluent areas, about 81% live near a pharmacy. On the other hand, 84.8% of the population lives within a 20 min walk of a General Practitioner’s (GP’s) office in England overall while the figure reduces to 19.4% in rural areas (Todd et al., Reference Todd, Copeland, Husband, Kasim and Bambra2015). The community pharmacy is the preferred location over a GP’s office, due to the ease of access (Todd et al., Reference Todd, Copeland, Husband, Kasim and Bambra2015). Pharmacy care is particularly vital in rural areas where primary care physician shortage is greater than urban areas. Furthermore, recruiting GPs to work in areas of high social deprivation is challenging and primary care is inadequate in such areas (Chenet and McKee, Reference Chenet and McKee1996; Todd et al., Reference Todd, Copeland, Husband, Kasim and Bambra2015). The UK doctors welcome the government plans to increase the role of pharmacists in diagnosing and treating minor illnesses (Eaton, Reference Eaton2008).

GPs can only allocate at most 10 min of their time/consultation, whereas pharmacists can see patients for 30 min or more (Deslandes et al., Reference Deslandes, John and Deslandes2015). However, in practice, pharmacist can rarely devote 30 min/patient for acute unscheduled care. Most GPs have insufficient time to answer patients’ questions about treatments (Petty et al., Reference Petty, Knapp, Raynor and House2003). Patients view the pharmacist as someone who is easier to talk to than a GP and someone willing to spend more time with them (Hassell et al., Reference Herrick2000). Community pharmacists are sometimes patients’ first point of contact with the health-care system. They act as referral agents to doctors and mediators to other health services, so they assume the gatekeeper role (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000). Pharmacists and nurses have supplementary and independent prescribing rights in the United Kingdom and no other country has such extended non-medical prescribing rights as the United Kingdom (Courtenay et al., Reference Courtenay, Carey and Stenner2012). Pharmacists can order and interpret some lab tests (Mossialos et al., Reference Mossialos, Courtin, Naci, Benrimoj, Bouvy, Farris, Noyce and Sketris2015). There is a raising demand for unscheduled care in the United Kingdom (O’Cathain et al., Reference O’Cathain, Knowles, Munro and Nicholl2007). Approximately 40% of GPs’ time is spent dealing with minor illnesses and about 8% of visits to the Accident & Emergency Departments (A&E) are for minor illnesses (Bednall, Reference Bednall2003; Pumtong et al., Reference Pumtong, Boardman and Anderson2011). Minor ailments cost the GPs £2 billion annually and Emergency Departments (EDs) £136 million annually (Paudyal et al., Reference Paudyal, Watson, Sach, Porteous, Bond, Wright, Cleland, Barton and Holland2013). Minor Ailments Schemes (MAS) were introduced more than a decade ago to reduce the burden of minor ailments on higher cost settings such as general practices and EDs. The United Kingdom does not have a national MAS but there have been calls for nationwide service (Paudyal et al., Reference Paudyal, Hansford, Cunningham and Stewart2011). A substantial potential cost savings can be made with the expansion of MAS nationally and in 2009, MAS saved £112 million for England alone (Paudyal et al., Reference Paudyal, Watson, Sach, Porteous, Bond, Wright, Cleland, Barton and Holland2013). At present, the list of minor illnesses treated under the MAS differ depending on the location – for example, England and Ireland. Government policy is promoting community pharmacy as the preferred setting for the management of minor ailments (Pharmacy Research UK, 2014).

In America, retail clinics are located inside pharmacies. An estimated 10.6% of the total population lives within a 5-min driving distance of a retail clinic, whereas 28.7% of the population lives within a 10-min driving distance (Rudavsky, Reference Rudavsky2009). In total, 55% of the visits to emergency rooms in the United States are for non-emergencies (Herrick, Reference Hassell, Rogers and Noyce2007). One study found that the public can save ~$4.4 billion annually by visiting the retail clinics for certain conditions, instead of EDs (Weinick et al., Reference Weinick, Burns and Mehrotra2010). The purpose of this review was to compare the UK’s MAS with the US’s retail clinic model. The health system needs in United Kingdom are changing, and the system must address cost, convenience and technological matters. The United Kingdom can benefit from looking at examples from other countries to help meet the current and future demands of health care.

Methods

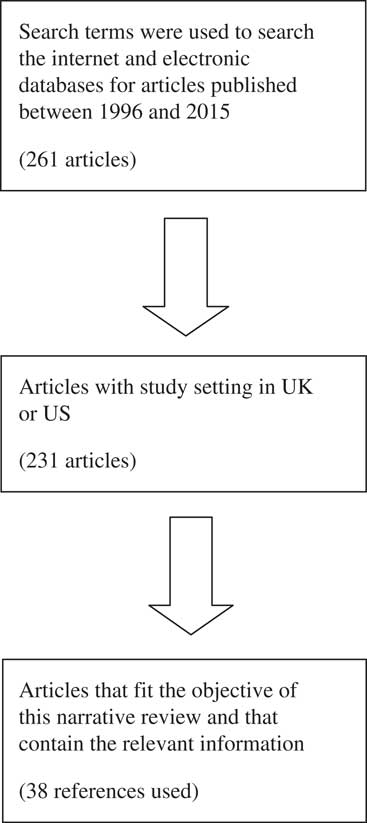

A literature search was done using the search terms: ‘Minor Ailments Scheme’, or ‘retail clinics’, or ‘minor ailments service’, or ‘community pharmacy’, or ‘pharmacy-based Minor Ailments Schemes’, or ‘walk-in clinics’. The search of electronic databases: MEDLINE, EBSCO, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar, was done for articles published between 1996 and 2015. An internet search was also carried out using the search terms. Only those articles where the study setting was in United Kingdom or United States were included in the review. Figure 1 shows the methods used for the narrative review.

Figure 1 Flowchart summarizing the steps used to screen information for the narrative review

Results

UK’s MAS

MAS in UK are run by pharmacists. The key studies of UK’s MAS are summarized in Table 1. The waiting time for a non-urgent GP appointment is approximately nine days and this is expected to increase further in the coming years (Todd et al., Reference Todd, Copeland, Husband, Kasim and Bambra2015). There is also a growth in waiting times for EDs (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2014a; 2014b; 2014c). No appointment is needed for MAS and the waiting times are short. They have extended hours including evenings and weekends. Examples of minor ailments included in the scheme are allergic rhinitis, pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, headache, haemorrhoids, diarrhoea, dyspepsia, cystitis, pain, respiratory tract infections, chickenpox, dermatitis and fungal infections (Paudyal et al., Reference Paudyal, Watson, Sach, Porteous, Bond, Wright, Cleland, Barton and Holland2013). Patients can self-refer to the MAS or they can be referred by a GP. The pharmacist can deal with minor ailments in three ways as follows: advice only, advice and supply of medicine, or referral to a GP. Pharmacists are reimbursed with a consultation fee and the cost of medicine supplied (Pumtong et al., Reference Pumtong, Boardman and Anderson2011). The cost of treating common ailments in community pharmacies is £29.30/patient. The cost of treating the same problems at A&E is nearly five times higher at £147.09/patient and nearly three times higher at GP practices at £82.34/patient (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2014a; 2014b; 2014c). People who are exempt from National Health Service (NHS) prescription charges (elderly, pregnant and children) receive medicine at no cost through the scheme.

Table 1 The key studies of UK’s Minor Ailments Schemes (MAS)

MAS complement GPs, and they do not compete with them. The schemes will allow GPs to spend more time on complex cases. The College of Emergency Medicine supports the minor ailment services (Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2014a; 2014b; 2014c). Moreover, the schemes encourage self-care of minor illnesses. The report by the ‘Self-Care Campaign’ stated that promoting self-care in patients can save the NHS £10 billion over the next five years (Self Care Forum, 2014). There is a lack of involvement of community pharmacists in telemedicine (Barr et al., Reference Barr, McElnay and Hughes2012). Pharmacies can be a key resource in the field of connected health care in United Kingdom (Barr et al., Reference Barr, McElnay and Hughes2012). Despite this, telehealth technologies are only being tested with GP practices (Barr et al., Reference Barr, McElnay and Hughes2012).

US’s retail clinics

Table 2 shows the key studies of US’s retail clinics. Not all pharmacies have retail clinics but their numbers are increasing. Most are owned by retail pharmacy giants such as Walgreens, CVS, Wal-Mart, Rite Aid and Target. Retail clinics in America employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) who can diagnose and treat minor illness, and minor injuries (Gray, Reference Gray2015). Patients of all ages can go to the retail clinics. They are 30–40% cheaper than physician offices and about 80% cheaper than EDs (Ashwood et al., Reference Ashwood, Reid, Setodji, Weber, Gaynor and Mehrotra2011). They have fixed prices for providing a particular treatment, and the price can be less if the patient has health insurance. Retail clinics have formed partnerships and affiliations with hospitals, patient centred medical homes and physician groups (CVS, 2015). After a visit, the PA sends a summary of the visit to the primary care doctor (CVS, 2015). Retail clinics are starting telemedicine programs, which will allow patients to be seen through a computer screen. Alternatively, patients can also come to a retail pharmacy and sit at a kiosk in a private room to interact with a health professional via video chat (CVS, 2015).

Table 2 The key studies of US’s retail clinics

Discussion

This is the first review study to compare the UK’s MAS with the US’s retail clinics. There are many similarities as well as differences between the two models. In both countries, most of the pharmacies that offer primary care services are owned by large chains and corporations, and there are no doctors involved in patient care. The community pharmacies are situated in convenient locations, offering after-hours services. In addition, they have a similar list of minor ailments and both are created to relieve the burden of minor ailments on doctors and EDs. The cost of care at both places is cheap. They are also responsible for saving money for health systems. They do not compete with GPs or EDs. Both MAS and retail clinics can deliver quality care and receive high level of patient satisfaction. The main difference is that in America, the insurance or the patient pays for the service and in the United Kingdom, pharmacists are reimbursed by the NHS. Another difference is that MAS have the support of the UK government. Furthermore, in MAS, pharmacists treat minor illnesses, whereas PAs and NPs provide care in retail clinics.

Both health systems can learn from one another. Rather than implementing a range of different primary care services, it is better to consolidate the existing services. Both MAS and walk-in centres offer nearly identical services, with the exception of treating minor injuries and wound care. Some walk-in centres are led by GPs while some are led by nurses. Similar to the retail clinics, community pharmacy MAS can combine with walk-in centres and NPs and PAs can practice alongside pharmacists. All UK pharmacies offer essential services but advanced and enhanced services are optional. The MAS is just one of the many enhanced services and UK pharmacists are already performing many health services for the public. PAs and NPs can take over some primary care workload from pharmacists and this would prevent the pharmacists from being overwhelmed with all their current duties. With the use of kiosks, one NP or PA can cover several pharmacies. Patients can come to a community pharmacy and sit at a kiosk in a private room to talk to a NP or PA. Furthermore, skilled pharmacy technicians can support pharmacists in dispensing medications so that pharmacists can engage in other health services. It was found that the lower the number of medicines that pharmacists dispensed, the greater the number of other health services that they can carry out (Schafheutle et al., Reference Schafheutle, Seston and Hassell2011).

At present, the staff at the walk-in centres are able to retrieve patients’ records to update any treatment or advice given at the centre (Arain et al., Reference Arain, Nicholl and Campbell2013). The pharmacist should have access to patient medical records to safely prescribe medicines. So, by merging, MAS will be able to retrieve medical records, and communicate with GPs about a patient’s visit, much like the retail clinics. This would promote continuity of care. The first pharmacy co-located with a walk-in centre opened in Merseyside in 2001 (Jesson and Wilson, Reference Jesson and Wilson2003). There are now many pharmacists working in walk-in centres (Mason, Reference Mason2000). More research is needed on the feasibility and practicality of combining walk-in centres and MAS. Moreover, as seen in retail clinics, MAS can form affiliations with hospitals, GP’s offices, medical helplines such as NHS 111 and EDs. That way, more referrals can be made to MAS. Finally, following the example of retail clinics, MAS can initiate the development of telehealth services. Home-bound patients should have the option of videoconferencing with a pharmacist. One limitation of this study was that a full comparative analysis of efficiency and equity of the MAS and retail clinic models was not possible due to their differences.

Conclusion

Community pharmacists should be increasingly involved in primary care. All things considered, the community pharmacy is a very suitable location for treating minor ailments. It is imperative that the public should be more aware of the services offered by the MAS. In conclusion, United Kingdom should have a national MAS offering identical services. The future holds great potential for the MAS but there is still room for growth. The schemes can learn from examples of health services from other countries. They must continue to change and evolve to meet the current and future demands of health care.

Acknowledgement

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.