Introduction

Over the last several years, important steps have been made – in academic organizations, with the promotion of collaborative networks, with the development, discussion, adoption of authoritative international declarations and charters – to define and promote, conceptually and institutionally, the role of general practice as a key player in research (Vuori, Reference Vuori1986; Improving Health Globally, 2004; Mant et al., Reference Mant, Del Mar, Glasziou, Knottnerus, Wallace and van Weel2004; Mendis and Solangaarachchi, Reference Mendis and Solangaarachchi2005).

Various groups of Italian general practitioners (GPs) have been part of this highly articulated movement, so far as to be also the hosts of important conferences, where the international achievements and the perspectives have been discussed in depth (Towards Medical Renaissance, 2006; European Journal of General Practice, 2008; The future of primary health care in Europe, 2010). The purpose of the ‘point of view’ proposed here is to contribute a reflection, which has a potential original role in the broader development of the above trends. While certainly marginal in the academic and institutional debates, Italian general practice has in fact had the opportunity of being extensively involved in field projects, which could be considered a concrete test of the feasibility and of the implications of a more research-centered primary care (PC).

The narrative approach adopted to present and discuss the contribution of an experience that has a very long history has appeared to be the most appropriate way to convey the spirit but also the substance of the main take-home message: there are no generally valid and a priori defined rules to give PC a clearer research identity: rather, conceptual, methodological and operational flexibility is the best way to ensure a solid compliance with the many unmet needs and the variable contexts of care that characterize PC.

Historical and conceptual framework

Regardless of its specific denomination across the variability of contractual and institutional national settings, primary, or general, or family, care or practice (considered here as synonyms, and referred to as PC) is assumed as the universe of the activities and actors, who are the primary (=basic, direct, permanent, comprehensive) interface of medicine (=knowledge, competence, technical know-how, culture) and the health values-needs (=diseases, symptoms, perceptions, rights) of a society.

The discussion of the hypothesis and of the proposal formulated in the title of this contribution must therefore be framed in the context of the questions that are at present more challenging in the relationship between health and society. The scenarios outlined in their essential elements in Table 1 can be considered as at least a reminder to a huge literature from different disciplines and sources (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Taylor and Marmot2010; Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2010; Gostin and Mok, Reference Gostin and Mok2010; Murray and Lopez, Reference Murray and Lopez1997; United Nations General Assembly, 2010; Van Puymbroeck, Reference Van Puymbroeck2010; Editorial, 2011b).

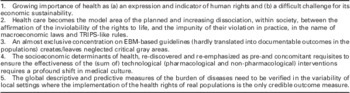

Table 1 The broader, inevitable, controversial frontiers of medicine ⇔ societyFootnote *

TRIPS = trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights; EBM = evidence-based medicine.

* For the references that support the various statements, see text.

Over from decades, field experiences of technical and cultural collaborations with PC groups and settings, in the North and the South of the world (Tognoni, Reference Tognoni1978; Bonati and Tognoni, Reference Bonati and Tognoni1984; Tognoni et al., Reference Tognoni, Alli, Avanzini, Bettelli, Colombo, Corso, Marchioli and Zussino1991), have also included a direct participation to the ‘research season’ of World Health Organization (WHO, 1977; Alma Ata, 1978; Tognoni and Franzosi, Reference Tognoni and Franzosi1982) and a confrontation with its controversial transformations (Tognoni, Reference Tognoni1998a; Reference Tognoni1998b; Anselmi et al., Reference Anselmi, Terzian and Tognoni2008).

It has been possible, therefore, to appreciate from inside the specifically ambiguous evolution of the roles attributed to PC actors in their relationship with the management of and the research on/in the different health-care systems.

Practitioners, family doctors, generalists were allowed and/or requested to be those who:

a) are in charge of transferring a knowledge produced in/by specialized academic and institutional circles to the majority of the patients (citizens? users? clients? tax-payers?);

b) must be carefully monitored for their compliance with recommended (institutional, diagnostic, therapeutic, economic) guidelines;

c) are allowed, invited or simply needed as occasional partners in research activities, to provide patients and data for any project promoted by the ‘scientific society’.

The important exceptions to this picture (eg, the fundamental contribution of the British Royal College of General Practitioners to the history of contraception) do not change the basic fact that the settings of ambulatory routine practice were not generally recognized in the role of producers of original knowledge.

As outlined in the general introduction, the situation has since evolved importantly, at least in terms of the awareness and of the intolerability of the anomaly, which, however, is still heavily influencing (and somehow dominating) critical areas:

• in an era of EBM-guided practice, meta-analyses and overviews, guidelines can hardly (if ever) make reference to evidence-producing trials whose intellectual property belongs to networks–societies of GPs;

• the international regulatory framework for clinical trials (Good Clinical Practice–International Conference on Harmonisation) has been clearly conceived and is enforced (with the well known and increasingly debated contradictions and difficulties, due to a misguided conception of quality assurance of research) without any specific consideration of the real settings of PC (Hoey, Reference Hoey2007; McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, Conway, Macdonald and McInnes2009; Ng and Weindling, Reference Ng and Weindling2009; DeMets and Califf, Reference DeMets and Califf2011);

• an even more fundamental risk could, however, be seen in the fact that PC appears to have accepted a mostly administrative interpretation of its otherwise critically important role of gate-keeper. The abundant–redundant production of many ‘studies’, which describe, evaluate, measure what happens and, what are its burden or costs, have been predominant with respect to large-scale, clinically and epidemiologically important research programs, looking for original answers to unmet needs.

An exercise of definitions as they have been field-tested

The hypotheses, the reflections and the proposals that follow are the collective result of a long story that sees as protagonists hundreds of Italian PC doctors, with a leading role of the very active groups of Centro Studi e Ricerche in Medicina Generale (CSeRMEG; CSeRMEG, n.d. 2011; Visentin, Reference Visentin2008). It is, however, of critical cultural and operational importance to recall here the complementary and parallel experiences conducted with the hospital and community Italian nurses with their 20-year-long program of ‘nursing research in daily care’ (PARI, Percorsi di Assistenza e Ricerca Infermieristica; Di Giulio et al., Reference Di Giulio, Saiani, Laquintana, Palese, Palese and Bellingeri2001; Editorial, 2002) and the health promoters of the Amazonia region in Ecuador and in urban Argentina (Anselmi et al., Reference Anselmi, Avanzini, Moreira, Montalvo, Armani, Prandi, Marquez, Caicedo, Colombo and Tognoni2003; Montalvo et al., Reference Montalvo, Avanzini, Anselmi, Prandi, Ibarra and Marquez2008; CECOMET (Community Epidemiology and Tropical Medicine), 2010).

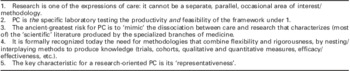

The core of the positions and of the proposals, which have been successfully tested over so many years and in very different scenarios, is summarized in Table 2, whose statements are best illustrated by going rapidly through the protocol and the ‘main’ results of a research project of Italian PC physicians.

Table 2 Definitions and terms of reference

PC = primary care.

The Rischio & Prevenzione (R&P) study, which for any has been chosen as a model scenario condition where practice does and must coincide with research is not an occasional exercise (Rischio and Prevenzione Investigators, 2010). It is a ‘confirmatory case’ of a long-term experiment testing the hypothesis that the coincidence research = practice is valid across the spectrum of contexts of medicine. It should be read as: research is one of the expressions of practice as well as: practice is a permanent opportunity for a methodologically well-tailored research.

To support the credibility of the hypothesis, it is worth recalling briefly two ‘historical’ experiences produced in a ‘primary care’ context in Italy.

In the early 1980s, the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI) trial tested and documented for the first time the survival advantage of an early reperfusion of patients admitted to general hospitals for an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) in the countrywide network of ∼200 National Health Service Coronary Care Units. Up to 12 000 patients were seen, diagnosed and treated over a period of 18 months for their ‘primary’ problem, Myocardial Infarction, according to the best local care. Only the uncertain-unknown decision related to the benefit–risk profile of thrombolysis was centrally randomized, in an open design, not interfering with, but simply integrating usual care. Uncertainty was transformed into an opportunity of highly innovative research, recognized also by regulatory approval, and commented on as a landmark of world cardiology (GISSI, 1987; GISSI, 1997; Sleight, Reference Sleight2004; Yusuf, Reference Yusuf2004).

In a more classical setting of PC, the approach of the Primary Prevention Project (PPP; Primary Prevention Project, 2001) was logically and methodologically symmetrical and consistent with the GISSI experience. As AMI for cardiologists, prevention care and therefore research is the primary responsibility of GPs, who are in charge of the comprehensive care and follow-up of the populations who are assessed and monitored for their risks in different contexts. If an uncertainty or an open question exists or arises, daily practice is the natural laboratory for adopting a research protocol. This is nothing else but the substitution/translation of the risk of making patients the object of empirical, that is, ignorance-based, decisions, with the recognition of patients as subjects with whom the uncertainties are shared on an equal basis with the purpose of producing more appropriate new knowledge. Patients are duly informed that an unusual procedure, randomization, is introduced into their care: not as an exposure to an ‘experiment’, but as the best way to take care of their need by using a methodologically sound approach. The information to the patient is the declaration that research is first and above all an alliance between responsible carers and collaborating citizen: although differently, both face the situation of unmet needs where appropriate care can only coincide with a research strategy (Tognoni and Geraci, Reference Tognoni and Geraci1997; Farmer et al., Reference Farmer, Milne and Walley2011).

Looking at and listening to the model scenario of R&P

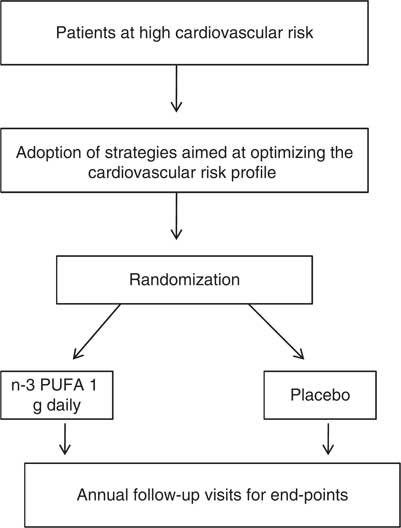

The flow chart of the study (Figure 1) sets out very clearly two components, methodologically well distinct but articulated as complementary in the protocol as well as in the minimal-essential package of data selected with the participant GPs, to properly reflect, not to burden, daily practice:

Figure 1 Rischio & Prevenzione study design; n-3 PUFA indicate polyunsaturated fatty acids

• an epidemiological outcome-oriented cohort aims to assess prospectively the degree of acceptability and the results of the implementation of recommended practices of prevention-control of the risks identified as inclusion criteria by the participating GPs;

• this typical effectiveness-oriented objective incorporates the formal randomized test of an experimental hypothesis: could fatal and non fatal out-of-hospital cardiovascular events, not covered by any of the existing strategies, be prevented with a drug registered for the early post-AMI period on the basis of a suggested anti-arrhythmic action (GISSI Prevenzione Investigators, 1999)?

While a carefully monitored observation is the normal design for the outcome-effectiveness objective, the randomized allocation of the same population to a treated versus a placebo arm transforms an epidemiological cohort into an experimental one: the same data, same endpoint events, same organization, same actors. Also, visually, the true nature of a trial, normally considered a foreign body with respect to routine practice, appears to be naturally nested in the prospective epidemiology of a population: data to be collected as inclusion criteria and for follow-up strategies have been carefully discussed, selected, piloted with participating physicians to reflect, not to burden their care practices.

The methodological assumptions adopted during the long preparatory phase (a truly interactive sequence of meetings in a Continuing Medical Education (CME) framework, followed by a formal epidemiological survey; Collaborative Group Risk and Prevention Study, 2004) are worth emphasizing:

a) The challenging data of the pilot phase documented that the most appropriate (=EBM based and patient-focused) practices could require an important dissociation from formal (=EBM based only) guidelines. The methodological implications are clear: there is a strong interaction between the objective documentation of risks (many and highly variable for quality and quantity) and the informed but inevitably subjective perception of this patient as the one at specifically higher risk-and-needing-prevention: the resulting variability must be documented as positive information, not as a potential confounder. Participant doctors were encouraged to abandon a rigid procedures-centered EBM/CME paradigm to become conscious of their need, and therefore opportunity, of producing original outcome data as the only measure of appropriateness.

b) The randomized allocation to a blind pharmacological intervention (with a well-established safety record) enters almost naturally into a practice, where so many and different strategies of care, both in terms of drugs and of life styles, are interplaying. The ‘normality’ of a trial nested in practice also promotes a dialogue with the patient while sharing information on her/his situation of cardiovascular risk prevention and management: the bureaucratic procedure of the informed consent becomes what it should be perceived and practiced: a way of expressing the civil duty of making an individual (well known to the GP) not principally a patient owing to her/his risk status, but an active actor of the research process.

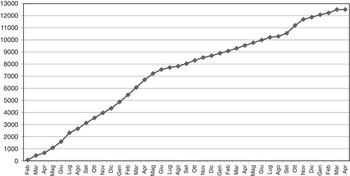

Translated into one of the classical images that represent the history of participation of patients to (not the recruitment into!) a trial, Figure 2 summarizes symbolically the feasibility of adopting as research questions two uncertainties that accompany medical practice. The points proposed in Table 3 reproduce what has been shared more frequently with the over 800 participant GPs over the seven years of R&P. They could also be seen as the summary of the reasons why this project is also of more general interest for the discussion of the hypothesis of this paper.

Figure 2 Timing and pattern of randomized patients into the R&P protocol

Table 3 Cultural, organizational and methodological lessons of a project testing the coincidence of practice and research

PC = primary care; GPs = general practitioners; GCP–ICH = Good Clinical Practice–International Conference on Harmonisation; CME = Continuing Medical Education.

It is easy to see that the literature has, over the last several years, widely debated most of the same points (Horton, Reference Horton2010; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Davis and Lypson2011). The ‘advantage’ of R&P – on a ‘representative’ scale and in a ‘representative’ context (see the fifth point of Table 2) – is to be the expression of a project that is not simply advocating but confirming, by field-testing it one at least of the possible responses to the needs and wishes expressed in the ongoing debates.

To make the issue of feasibility even clearer, it is useful to close this section by also quoting two other projects, which have been running in parallel with R&P, along the same line of testing the yield of making the uncertainties and the unknown of PC an opportunity of research.

a) Observation as generator of knowledge (Osservare per Conoscere – OpC, Project, 2006) was a project born as an exercise of permanent education and assessment of appropriateness. The operational protocol became a combination of a transversal (on an index day) and a longitudinal (over a five-year period) observation of the complexity-fragility of a population of 75 000 persons aged ⩾75 years. Few ad hoc data collected in a routine home visit were integrated with the administrative data routinely documenting the activity of all the PC doctors of the Veneto region to produce a very articulated profile of the correlations between the quality of care, the degree of autonomy, the attributable burdens of care and the degree of avoidability of adverse clinical events.

b) The recently completed Italian Study on Depression (ISD; Gruppo di Lavoro ISD, 2007), where almost 300 GPs across the country have included up to 2500 of their patients in a prospective cohort, to test the implications (in terms of diagnostic-therapeutic behaviors and outcome over a 12-month period) of basing their clinical decisions on an informal check-list derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV, cross-checked (if needed) with the use of one or the other formal scale of depression.

While it is clearly not possible to present–discuss here in detail the characteristics and the results of the two protocols, it is worth underlining that simply making explicit a question from inside practice has led to the generation of knowledge without creating a separate body of procedures, rules or criteria for action. The formulation and the implementation of protocols becomes a preferred tool of a CME interpreted primarily not as a reiteration and recommendation of what is known, but the opportunity of stressing what is uncertain or unknown: not to wait for somebody else to produce answers (anytime in the future and elsewhere), but to assume the ‘normal’ responsibility of considering the production of new knowledge as the best indicator of the quality of care.

A way forward

The scenarios and the perspectives that have been proposed do represent a challenge that is by no means easy or straightforward to pursue and generalize. The global conflicting trends recalled in the frameworks of Table 1 have affected profoundly and increasingly societies and general policies and not simply health care and its actors.

The sequential order of the adjectives chosen to qualify the lessons in the title of Table 3 is not casual. As citizens and health workers, we are facing first of all a cultural threat: the legitimacy itself of imagining strategies targeted to unmet needs and innovative solutions is in many ways denied. The constraints of economic scarcity and sustainability are advocated (far less solidly documented) to impose as absolute priority to containment policies and contractual-organizational restrictions. PC is one of the preferred targets of the pressure to be compliant with a conception of health care as a market variable, more than as a project aiming at the promotion of the right to a more healthy and autonomous life.

The challenge of making research a ‘normal’ practice (Table 2) responds to the needs of assuring to PC an identity not of passive obedience but of cultural visibility and autonomy.

The experiences that could be developed in Italy (where a dramatic cultural and political crisis has been unfolding over the last several years) are also the product of an institutional intuition by the former director of the Italian Agency for drugs (Dr N. Martini), who interpreted its regulatory role not as a multiplication of controls but as a promotion of innovative research policies. PC specifically was declared, and concretely recognized with an ad hoc law and financial support, the privileged place where public health-oriented research is most needed, to face the universally denounced but yet unmet challenges of chronicity, complexity and frailty of the populations (Editorial, 2008; Turone, Reference Turone2010). The cultural and institutional ‘dream’ of one of the key figures of contemporary research and public health, the former president of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, is an even stronger indicator of, and framework for, the need to believe that contagious broad-minded strategies of research are the only way of giving credibility and legitimacy also to the health-care professions (Marmot, Reference Marmot2010).

PC is specifically challenged, in each country and even more at the regional level (not only in Europe, possibly even more urgently in the societies of the many Souths of the world), to become a cooperative reality capable of producing knowledge tailored to the concrete and highly differentiated contexts of life and health care. It is certainly curious, and worrying, to see that cooperative research networks have become a normal resource for almost all specialized disciplines, while cooperative national, let alone international, networks are still a rare and far less visible expression of PC, although increasingly recognized as an absolute priority (Beasley and Karsh, Reference Beasley and Karsh2010; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Lester, Kendall and Bryar2011; Starfield, Reference Starfield2011).

The problems for an agenda not limited to the (self)-description of what happens and is done, but capable of adopting outcome-oriented strategies for neglected areas (from cardiovascular ‘epidemics’, to behavioral–mental problems, to inequalities) are certainly not lacking (Anand and Yusuf, Reference Anand and Yusuf2011; Editorial, 2011a; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Francis and Ryan2011; Walport and Brest, Reference Walport and Brest2011).

In this direction, it is high time to forget–transform the many CME events and courses (which are most often, despite the ever more sophisticated interactive and e-based teaching–learning methodologies, a passive exercise in becoming obedient followers of the mainstreams) into collaborative, long-term, original field projects. If the ‘practice ⇔ research’ paradigm is adopted, the certainly critical issue of resources could become far less important. Universally available databases and the diffuse presence of PC actors are a powerful opportunity, easily integrated, when needed, with essential ad hoc data and non-medical participatory collaborations. If few model studies could be seen as a priority to be activated (not only wished for or piloted) at the European level, it is reasonably foreseeable that the project of a PC as protagonist–producer of original knowledge could become a cultural, organizational, methodological reality, and an important stimulus and partner also for the many Souths.

Acknowledgements

Warmest thanks to Mrs. Teresa Di Campli, Mrs. Paola D'Ovidio and Mrs. Maria Grazia Mencuccini for the wise and patient secretarial assistance.