Political science maintains a robust book tradition. For many scholars, authoring a book is crucial for advancement. Moreover, according to American Political Science Association (APSA) membership data, women remain more likely to belong to qualitative research networks and less likely to participate in quantitative research networks (Shames and Wise Reference Shames and Wise2017; Unkovic, Sen, and Quinn. Reference Unkovic, Sen and Quinn2016). Therefore, a book’s space to expand arguments and apply a wider variety of methodological approaches than typically seen in top-ranked disciplinary journals might provide a key outlet for women in political science.

This article investigates authorship and citation patterns of political science books. First, building on research that documents a gender gap in journal-article publication in the discipline (Breuning and Sanders Reference Breuning and Sanders2007; Evans and Moulder Reference Evans and Moulder2011; Østby et al. Reference Østby, Strand, Nordås and Gleditsch2013), we explored both the overall proportion of women among authors as well as trends in authorship patterns over time. We found that the “gender gap” for books is slightly wider than for articles: books with only male authors comprise about 69% of the total, whereas Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017, 438) found that the proportion was about 65% for articles in top journals. Furthermore, as with articles, men are overrepresented as both solo authors and collaborators, adding to evidence that women do not benefit equally from the discipline’s shift toward coauthorship (Djupe, Smith, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Smith and Sokhey2018). We also found that women’s underrepresentation as book authors increases with academic rank. This is important because full professors are the first authors for almost half of all books by academic political scientists. However, within this group, women are only 16% of first authors, despite holding 28% of positions in the discipline. To understand the gender publication gap for books, we conducted interviews with acquisitions editors. Key revelations from these conversations include editors’ lack of awareness of the problem, lack of systematic data collection about book submissions, the relative opacity of the book-publishing process, and the weight of network effects that may slow women’s advancement.

We found that the “gender gap” for books is slightly wider than for articles: books with only male authors comprise about 69% of the total, whereas Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017, 438) found that the proportion was about 65% for articles in top journals.

We then examined the impact of books in terms of citations for a random subsample of titles. Somewhat surprisingly, given findings of gender citation gaps for journal articles (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Sumner and Mitchell2018; King et al. Reference King, Bergstrom, Correll, Jacquet and West2017; Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013; Peterson Reference Peterson2018), we found that books authored by one woman receive as many citations as those authored by one man or teams of men. However, books authored by collaborative teams of women or teams of men and women receive far fewer citations, on average, than books by one man or one woman or by teams of men.

For many scholars, a book may be more important for tenure, promotion, and salary decisions than an article at a top journal (or even two or three articles). At the assistant-professor level, for example, a scholar’s most notable output may be a book. Given this, gender publishing and citations gaps can have enormous implications for the evolution of women’s status in the profession (Alter et al. Reference Alter, Clipperton, Schraudenbach and Rozier2020; Teele Reference Teele, Elman, Gerring and Mahoney2020)—especially because, in terms of citations, books have far greater impact than journal articles (Samuels Reference Samuels2013). Work on the gender gap in journals has sparked a conversation among journal editors and within APSA about the sources of women’s underrepresentation in journals’ table of contents (Brown and Samuels Reference Brown and Samuels2018). Likewise, we hope our findings generate discussion among and between scholars and publishers about the sources and implications of women’s underrepresentation among book authors.

DATA

To assess the distribution of book authorship by gender, we started with what is plausibly the universe of book publishers in political science: all presses that hosted a booth at the 2016 APSA Annual Meeting, plus any other publisher listed in Garand and Giles (Reference Garand and Giles2011). We then compiled lists of books that these publishers classified as “political science” between 2004 and 2015. To do so, we contacted each publisher and requested a list of said books. If we did not receive a response, we compiled the books by scraping publishers’ websites. This generated a list of 25,898 books from 34 university and 22 commercial presses.

University presses published about 32% (8,250) of all books during this period and commercial presses published the remainder (17,648). We assigned a subfield to each title—American politics, international relations (IR), comparative politics, political theory, or methodology—by making educated guesses using titles, abstracts, and/or information that publishers provided about the content of each book. Given the volume of books, we coded subfields only for university-press books.

We then classified authors’ gender using the “Gender Balance Assessment Tool” created by Jane Lawrence Sumner at the University of Minnesota (Sumner Reference Sumner2018). This program assigns a gender to names probabilistically. Using online searches of authors’ websites, we manually checked all names that the program gave lower than 90% probability and assigned the likeliest gender identity using photographs and gendered pronouns in descriptions of authors’ work.

The following discussion reports figures for both commercial and academic presses. However, most of this article focuses on university-press books, which are more important for scholarly advancement. Doing so also provides a reasonable “apples-to-apples” comparison to results that Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) presented for journal articles: similar to articles but unlike most commercial-press books, university-press books are peer reviewed.Footnote 1

RESULTS: GENDER PUBLICATION GAPS

Combining university and commercial presses, books with only male authors comprise 69.1% of the total. Books with only women among authors comprise only 19.6%, and those with mixed-gender author teams comprise 11.2%. Table 1 divides the data into university and commercial presses, according to one of five categories: man solo author, woman solo author, all-men coauthorship, all-women coauthorship, and mixed-gender coauthorship. Combining the first two categories, we found little difference between commercial and university presses—one or more men write 68.5% versus 70.6% of all books. Women are more likely to publish a book on their own with a university press than a commercial press (20.7% versus 15.8%) but are less likely to publish a book written with another woman with a university press (1.5% versus 2.7%). The most significant difference appears in the last category: women are only about half as likely to write a book with at least one man at a university press than at a commercial press. These figures suggest that women are even less well integrated into collaborative writing networks for university-press books than they are for journal articles, regardless of whether they are working with other women or with men (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017).

Table 1 Distribution of Authorship for Commercial and University Presses

About 30% of university-press books published from 2004 to 2015 had at least one woman’s name on the byline. Does that make women underrepresented? Determining a benchmark is not straightforward. On the one hand, the proportion of women among book authors is higher than the share of articles with women as first authors in 10 top journals between 2000 and 2015 (26.7%). Yet, on the other hand, the proportion is still significantly lower than the two benchmarks that Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) suggested: women’s share of political science PhDs granted (38% in 2016) and women’s share of APSA members (38% in 2015).Footnote 2

It is worth noting that the gender gap in book publishing has narrowed somewhat over time: overall, the total share of women among authors rose by one third between 2004 and 2015, from 21% to almost 28%. However, this is still less than the proportion of women in the discipline. Figure 1 tracks the time trends of the five authorship categories for university presses. In the early 2000s, books by one man accounted for 63% of the total; however, by 2015, that proportion had declined to 54%. Most of the increase in the share of women among authors came from growth in the proportion of women’s solo publications (19% to 23%) and participation in mixed-gender teams (5% to 8%).

Figure 1 Authorship Patterns Over Time, University Presses

This minor increase in the proportion of mixed-gender collaborations is the only evidence of an increase in women’s coauthorship of books. Yet, in stark contrast to patterns for articles described by Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017), the proportion of books coauthored by either men-only or women-only teams has barely increased in recent years. Although the proportion of mixed-gender collaborations has increased to 8% of the total, it is still only one third the level observed for mixed-gender coauthorship in top journals (24.5%). In short, as solo book authors, women have made significant advances on their own (20% of the book total versus only 15% of the journal-article total), but not as collaborators—either with women or with men.

…as solo book authors, women have made significant advances on their own, but not as collaborators—either with women or with men.

The shrinking gender publication gap over time raises the question of whether women are more or less underrepresented in different ranks. From the 5,631 university-press books published between 2004 and 2012 (i.e., six years before our research because we also collected information on citations gaps), we drew a random sample of 1,170 titles: 1,000 from the full dataset, balanced on authorship pattern and subfield, and an additional 170 randomly oversampled from coed and all-women teams, which have relatively fewer books. This provided a sample of 21% of the total. We kept all books authored by academic political scientists (about 6% were not) but eliminated reprints, including those written by long-deceased scholars (137) and deleting paperback editions of previously published books (65 more), resulting in 613 books.

Using biographical information on each book’s back cover (cross-checked with institutional or personal web pages), we collected information on the rank of first authors at the time of the book’s publication. We found that the gender publication gap, when compared with the proportions of women at each rank, is wider in more senior ranks: at the assistant-professor level, women are 38% of first authors and 43% of APSA members; at the associate-professor level, 35% of first authors and 40% of APSA members; and at the full-professor level, only 16% of first authors and 28.6% of APSA members.

Subfield Patterns

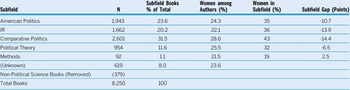

Table 2 addresses the question of whether gender publication gaps vary across subfields. Baseline information on women’s share in subfields is from field-specific APSA memberships listed in Hardt et al. (Reference Hardt, Kim, Smith and Meister2019). IR has the smallest share of women among book authors (21%), whereas comparative politics has the largest (28%). Yet, in both groups, there is an approximate 14-point gap in women’s book publications vis-à-vis their presence in the subfield. There are relatively few methodology books; within that subfield, women authors are 21% of the total. This means that in methodology, women comprise a larger proportion of book authors than APSA members in that subfield; however, we should not overstate this finding given the small number of methods books. In all other subfields, women are underrepresented among authors relative to their numbers in those fields.

Table 2 Summary Statistics by Subfield, University Presses

Figure 2 explores the proportion of women among authors by subfield over time. We excluded methodology because low numbers mean that the publication of a single book by a woman in a given year throws off the proportions. The figure shows that in political theory, the proportion of women among authors has remained constant. In contrast, the proportion of women among authors has increased in American politics (20% to 25%), IR (18% to 25%), and—most notably—in comparative politics (22% to 32%). However, despite these gains, the proportion of women among authors remains lower than the contemporary proportion of women in each subfield.

Figure 2 Percentage of Women Among Authors by Subfield, 2004–2016

Note: Dotted lines represent women’s membership in the subfield reported in Hardt et al. Reference Hardt, Kim, Smith and Meister2019.

Explaining the Gender Book-Publication Gap

As in journal articles, a gender gap in book publishing exists in political science: women publish relatively fewer books than their numbers in the discipline might predict. Moreover, although the gender book-publication gap has narrowed over time, it remains larger than for articles in top journals by about 5%. Most of women’s relative gains have come as solo authors, but they remain far less likely to collaborate on books than on articles. Within subfields, the gender book-publication gap is most significant and has remained unchanged in political theory. It has narrowed somewhat over time in IR and American politics and mostly in comparative politics.

To better understand the roots of the book-publication gender gap, we conducted informal telephone and Internet audio interviews with political science acquisitions editors from one commercial press and seven university presses (three men and five women).Footnote 3 These professionals had at least 175 combined years of editorial experience. Our discussions with them suggested several reasons why a book gender gap may exist.

First, in contrast to the attention focused on the gender balance of article publishing in recent years, which in turn raised attention among journal editors (Brown and Samuels Reference Brown and Samuels2018), our interviews revealed that the gender balance of book authors is not yet a topic of wide concern among book editors. One editor affirmed that “Nobody ever raises the issue; I don’t even know who I’d raise the issue with. We just assume we are doing alright.” Another stated that “There has never been a discussion in five years at [our press] about finding more women. Maybe we need to do more of that, be more proactive.” Even at a press where the issue of gender balance has been discussed in recent years, the editor could not confirm that anything had actually changed: “I don’t really know—I think my author list is pretty balanced…[but] it’s possible that there are patterns I just don’t pick up.”

Second, even for editors who stated that gender balance is a concern at their press, book editors lack the type of information that journal editors possess that could help identify a gender gap. It is not only that books are submitted and evaluated differently from journal articles. The issue is that every editor we spoke to confirmed that presses keep no records at all of information relevant to the editorial process—including the number of submissions, rejections, and acceptances or any type of author-demographic information. Given this, book editors could provide only rough estimates of the number of submissions per year or the gender balance of published books. (Two had counted the number of books they had published in the previous year and the proportion of women authors immediately before the interview.) Given the relative lack of attention to the issue and their lack of information, editors must rely on guesswork to track the balance by gender (or rank or ethnicity) of published books—whether the press receives a few dozen or several hundred submissions per year.

Third, book editors’ professional incentives also may slow responses to demands for attention to a gender gap in publishing. The editorial process for book publication is not only less transparent than the (already opaque) article publication process; book editors also face relatively fewer incentives to improve transparency. They are not nominated and hired by teams of professional colleagues as are many journal editors, they do not have to publish annual editors’ reports, and they do not answer to editorial boards of professional colleagues. Their professional incentives also differ from those of journal editors, who typically serve relatively brief terms and then return to their academic positions in which they must continue to produce journal articles and book manuscripts.

Fourth, because they are not colleagues, book editors do not participate as directly in APSA or other professional association task forces or in other activities focused on bringing attention and conducting research on issues related to women’s professional advancement.

Factors specific to the book-publishing process also may contribute to the gender gap in book publications in political science. Most important, book and journal editors differ in their discretion to solicit and publish manuscripts. As our interviewees confirmed, unlike journal articles, most book editors solicit a sizeable proportion of manuscripts that they eventually publish, and they publish relatively few submissions that arrive “over the transom.” Most editors described the creation of their lists in an alchemic way, suggesting that their experience has given them “a good nose” about which books to publish. They also often noted that book publishing is a business, meaning that they need to acquire titles they believe will sell (although they acknowledge that a few books with high sales subsidize the publication of most others). Yet, when pressed, not a single editor suggested that they had evidence that women’s books sold fewer copies than men’s, and several could immediately name books bylined by women that sold very well.

Editors also acknowledged that the nature of book publishing might slow down change because it can perpetuate an existing network of authors and their advisees. Due to the slow pace of cohort replacement, this may retard growth in the proportion of women authors. After all, to the extent that women are less central to a network of senior male scholars who publish books, fewer women are likely to be recommended to publishers. In addition, the single-blind peer-review process for books—in which reviewers know the author—may hold women to tougher standards than men, resulting in their manuscripts taking longer in the review and revision phases (Hengel Reference Hengel2017). This “time tax” could be much longer than for any single article, further undermining women’s long-term productivity relative to men.

A potential manuscript “submission gap”—driven by both publishers’ and senior male scholars’ networks—also may help to explain the book “publication gap.” In addition to network effects, women may write and submit fewer book manuscripts due to perpetually high academic service loads (Alter et al. Reference Alter, Clipperton, Schraudenbach and Rozier2020); child-bearing and -rearing duties may reduce women’s productivity (i.e., the “mommy penalty”); and women might produce higher-quality work that takes more time (Hengel Reference Hengel2017). These factors may make women more risk averse. For example, given that women are relatively more underrepresented at some presses than others (see appendix figure A.2), just as with journals, it is possible that women perceive the likelihood of success at those presses differently from others (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Horiuchi, Htun and Samuels2020; Djupe, Smith, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Smith and Sokhey2018). Without editorial data about the number of submissions that presses receive, the number that are sent out for review, and the publication trajectories of each reviewed manuscript, several of our hypotheses are difficult if not impossible to test. Nevertheless, we encourage editors to conduct internal audits of the nature explored in Brown and Samuels (Reference Brown and Samuels2018).

RESULTS: GENDER CITATION GAPS

Our second focus in this article concerns whether books written by men and women receive different levels of recognition, as measured by citations. Given the growing use of tools such as Google Scholar, this is an important question. Within our subsample of 613 books by academic political scientists that were not reprints or paperback editions, 72 were written by a coed team (12%), 12 by an all-woman team (2%), 108 by women working alone (18%), 81 by an all-man team (13%), and 340 by men working alone (55%). We were able to find citation information for all but five of these books.

Figure 3 provides average citation counts from Google Scholar for political science titles after six and at least 10 years for these authorship categories. The figure presents citation counts from Google Scholar for a random sample of (non-reprint) books written by academic political scientists. The first column calculates the citation count six years post-publication. The second column calculates the all-time citation averages for books older than 10 years at the time of data collection.

Figure 3 Citation Patterns by Type of Authorship

We found surprising patterns. First, six years post-publication, books written by women working alone do as well, on average, as those written by one man or teams of men. (A t-test for the difference of means for books written by one woman versus one man or teams of men failed to reject the null of no difference.) Six years out, books by teams of men perform slightly better than books written by men working alone (i.e., the one-sided p-value is 0.075). Books written by coed teams lag behind all of the other categories except books written by all-women teams, which fare the worst. Indeed, books written by teams of women appear to be poorly recognized, receiving only 35 citations, on average, six years after publication compared with an average of 82 for books written by men working alone and 89 for those written by women working alone.Footnote 4

…books written by women working alone do as well, on average, as those written by one man or teams of men.

Other striking gaps emerged when we considered books that are at least 10 years old. Overall, books by teams of men accrue the most recognition, followed by books bylined by a man working alone. Although there are no statistical differences between these two categories and books written by women working alone, coed teams and all-women teams again performed substantively worse. After more than 10 years, books written by teams of men received seven times the number of citations as books written by teams of women. Mixed-authorship teams also fared poorly in terms of citation counts after more than 10 years (i.e., the one-sided p-value for difference of means between men’s teams and coed teams is 0.034). These gaps are substantially larger than what has been found for articles. For example, Maliniak, Powers, and Walter (Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013) found that by the 2000s, articles authored by women received about 90% of the citations of articles authored by men.

Academic Rank and Gender Citation Gaps

One concern with exploring gender citation gaps by authorship type is that—as noted previously—not only are men and women unequally distributed across professional ranks, the gender publication gap also is larger at higher academic ranks. As Peterson (Reference Peterson2018) noted, the citation gap for journal articles has narrowed in recent years to more closely match the gender distribution of scholars. He suggested that this is due to a legacy of male dominance in the discipline, which is changing slowly as citation norms change and as more women advance up the ranks. Does the citation gap also widen as authors “age” in our dataset for all the well-known reasons, such as that women are less likely to appear on graduate syllabi and men are more likely to self-cite?

Figure 4 reveals few differences in citation patterns for books based on gender and rank. Within ranks, books with a woman as the first author do not receive less recognition than books with a man as the first author (there are no statistically significant p-values using difference of means tests). However, books with men as first authors are more likely to fall outside of the interquartile range of the distribution of citations at every rank. In other words, there are more highly cited outliers among the books on which men’s names appear first.

Figure 4 Citation Patterns by Rank and Gender

Note: Analyzes for random sample of political science books six years post-publication.

In summary, we found no consistent gender citation gap for books. Books by one woman receive about the same number of citations both six and 10 years post-publication as books by one man or teams of men. However, books by mixed-gender teams fare somewhat worse than others, and books by teams of women fare the worst. We also found no clear citation gaps within ranks. It is not clear why these patterns emerge. There is no clear reason why, for example, books by teams of women might be “niche” books whereas books by one woman would not.

DISCUSSION

Our findings include both good news and bad. To begin with the relatively good news, in contrast to results for journal articles, there are no clear gender citation gaps for books—at least those written by one woman. However, books by teams of women or by mixed-gender teams receive fewer citations than books by one woman or one man or by teams of men; perhaps this reflects women’s relatively weaker integration into collaborative research networks. Yet, there is some bad news: although most women receive relatively equal recognition for the books they write, and although the gender book-publication gap has narrowed over time in most subfields, women are still writing fewer books than men, and men’s books are more likely to be among the most “highly cited” in the discipline over the long term. Women remain underrepresented as book authors relative to their numbers in the discipline—across ranks and across subfields—and remain relatively more underrepresented as book authors than as journal authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication materials can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HN1I8Y.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paula Armendariz and Carly Coons for research assistance, and Lisa Baldez, Nadia Brown, Yusaku Horiuchi, Mala Htun, Josh Kalla, Dorothy Kronick, Jane Lawrence Sumner, Amy Erica Smith, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments.

APPENDIX: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS BY PRESS

Figure A.1 shows the aggregate proportion of women among all authors for each university press. Presses at the low end of the scale include Yale, Missouri, Kansas, and Kentucky, none of which break 15%. Minnesota, Syracuse, and Illinois are the highest, each with at least 45% of authors who are women.

Figure A.1 Proportion of Women Among Authors for University Presses, 2004–2015

Note: Numbers by each press name represent the average share of women among authors in the period.

Has the gender gap narrowed over time at particular presses? Figure A.2 lists the proportion of women authors over time for each university press. At most presses, the proportion is fairly constant; at others, we see an increase. For example, Cambridge averaged 27% over the sample but reached 50% in 2015.

Figure A.2 Women as a Percentage of Authors by University Press, Over Time