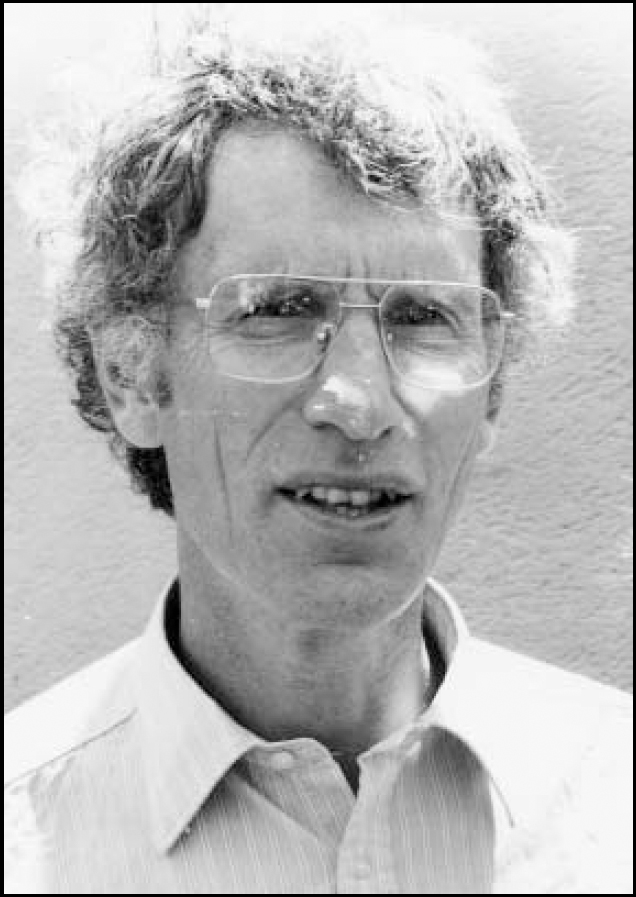

Jeremy Holmes is a Consultant Psychotherapist in North Devon, Visiting Professor at University College London (UCL) and Senior Clinical Research Fellow at Peninsula Medical School. He trained at Cambridge and UCL. His interests include personality disorder, attachment theory and acute in-patient wards.

If you were not a psychiatrist, what would you do?

GP, teacher, or (in my dreams) sportsman, musician or writer.

What has been the greatest impact on you personally?

A wonderful niche where I can put my neuroses to good use and satisfy my curiosity about how other people experience the world; a haven for conventionality and rebelliousness.

Do you feel stigmatised by your profession?

Not much - I see it as a challenge to convince other medical disciplines that psychiatry is a valid and useful branch of our profession.

Who was your most influential trainer, and why?

Heinz Wolff - because he had the Socratic gift of empowering young people - listening to them, inspiring them with a dream and encouraging them to follow it.

Which book/text has influenced you most?

The Divided Self - R. D. Laing.

What part of your work gives you the most satisfaction?

Listening and talking to patients.

What do you least enjoy?

Filling in‘Consent to Treatment’ forms.

What is the greatest threat facing the profession?

Going the way of social work which used to be a beacon of therapeutic skill in working with patients and families (and from whom psychiatrists could learn hugely) and is now demoralised and devalued - i.e. abandoning working with patients and being therapists, and becoming managers and risk assessors.

What single change would substantially improve quality of care?

Taking psychological therapies seriously, and not being driven exclusively by what are essentially arbitrary and possibly not even fully evidence-based NSF [National Service Framework] targets.

What conflict of interest do you encounter most often?

Between the time needed to do a good job and the demands of the mental health bureaucracy - review tribunals, S 117 meetings, etc.

Do you think psychiatry is brainless or mindless?

Neither - I think it is in quite good shape, actually. Neuroscience and psychological therapies are both in a phase of rapid development. We need to find ways of integrating them.

What is the most important advice you could offer to a new trainee?

Take on patients for psychotherapy from the start, get a good supervisor, stimulate your curiosity about people and what makes them tick. Follow your own interests, don't be intimidated by the curriculum, follow your own dream, remember there are lots of jobs out there, find your niche, hold onto your humanity!

What are the main ethical problems that psychiatrists will face in the future?

The conflict between the ethical duty to a particular patient and a wider ethical/political duty to a community - how to balance the needs of one against the needs of many. Getting the right balance between control and duty to society (who pay our salaries) and the wishes of the individual patient. How to maintain our pre-eminent position among health professionals, while staying true to the principle of multidisciplinary work.

How would you improve psychiatric training?

Make it more multidisciplinary - combine forces with clinical psychology and possibly mental health nursing and social work training; put psychotherapy at the heart of training; put even more emphasis on interviewing skills and use of video-tapes as part of assessment for the Membership à la MRCGP [Royal College of General Practitioners].

How should the role of the Royal College of Psychiatrists change?

Develop a much clearer model for the role of the consultant psychiatrists. Be less obsessed with catchment populations and define more clearly the functions of the consultant. Emphasise the role of the consultant as a therapist; involve consultants who are medical managers and medical directors more; find some way to work more closely with the BPS [British Psychological Society] and RCN [Royal College of Nursing] and RCGP - our natural allies (as well as to an extent, rivals).

What is the future for psychotherapy in psychiatry training and practice?

Should and must be central. Psychotherapeutic skills give psychiatrists confidence, puts them on an equal footing with clinical psychologists; enables them to provide what patients want. Every consultant psychiatrist should have an‘oasis’clinical day where he or she runs a special service of some sort which more often than not will be psychotherapeutic - CBT [cognitive–behavioural therapy] or family therapy or group therapy for particular disorders e.g., mood disorders or personality disorders. Most of the time we are cutting corners, making do and mending - here we can do our best to the limits of our knowledge and skill.

What single area of psychiatric research should be given priority?

Psychological therapies - still relatively neglected as drug therapy and the organisation of services take precendence over what is actually said and done, and how.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.