Robert Gardiner Hill, house surgeon, and Edward Charlesworth, physician and governor, at the Lincoln County Asylum are generally regarded as being the pioneers of the non-restraint movement in the UK, having totally abolished the use of mechanical restraints at that institution by 1838 (Lincolnshire Archives, 1838; Reference SmithSmith, 1999). John Connolly introduced non-restraint to the Hanwell Asylum in the summer of 1839, closely following Lincoln (Reference Hunter and MacalpineHunter & Macalpine, 1968). However, Gardiner Hill suggested the credit for introducing non-restraint in its full extent should go to Dr Thomas Prichard of the Northampton Asylum (Reference HillHill, 1857).

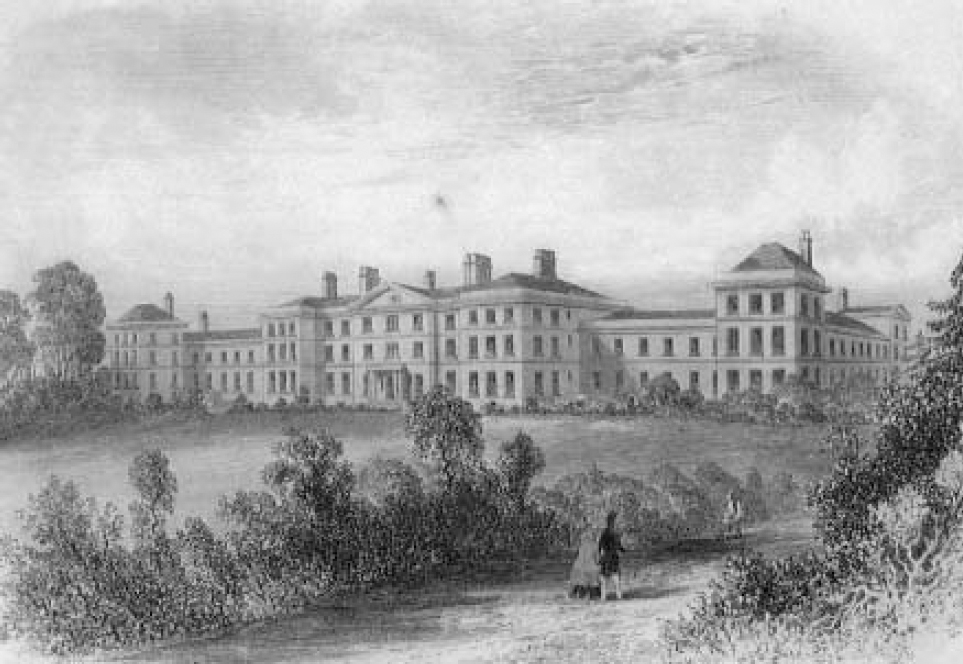

The Northampton Asylum (now St Andrew’s Hospital) opened its doors to ‘ private and pauper lunatics’ on 1 August 1838 (Fig. 1). The hospital, a charity founded by public subscription, was originally built to take 82 patients (‘52 patients of the fifth class and 30 private patients of the preceding, superior classes’ (Reference Hunter and MacalpineHunter & Macalpine, 1982)) but like many asylums it was soon forced to expand, owing to pressure from the parishes to admit pauper lunatics. Thomas Octavius Prichard (Fig. 2) was appointed as the hospital’s first medical superintendent at the age of 30 (Reference Foss and TrickFoss & Trick, 1989). Prichard believed that insanity required prompt and early treatment in asylums to maximise patients’ chances of recovery. He saw non-restraint as part of ‘a system of kind and preventative treatment, in which all excitement is as much as possible avoided, and no care omitted’ (Northampton Record Office, 1840).

Fig. 1. The Northampton Asylum, c.1845.

Fig. 2. Thomas Octavius Prichard.

By October 1840, the Committee of the Northampton Asylum in their second annual report (Northampton Records Office, 1840) stated that only a single patient had been ‘subject (beyond temporary confinement in his room or the seclusion of a separate airing ground) to any species of mechanical restraint’ and that this incident had occurred during Prichard’s absence and was terminated by him on his return (Northampton Record Office, 1840). Samuel Tuke of the York Retreat inspected the Northampton Asylum in October 1839 and wrote in the visitors book, ‘I have visited this Establishment with much satisfaction. The entire absence of restraint, with the general prevalence of order and quiet, is very striking.’ Prichard himself wrote in his second annual report of 1840 that ‘at the opening of this Establishment every patient was set at liberty immediately after admission’. However, later in the same report he contradicted himself when describing a male patient, who after admission, was placed in mechanical restraints for some months.

Using the original case records and hospital reports this paper explores the evidence for and against Prichard being the true pioneer of non-restraint in this country.

Method

The case notes of the first 50 patients admitted to the Northampton Asylum were examined for demographic and clinical details, including any past history of violence, and whether or not the patient had been subject to mechanical restraint previously, at the time of admission, or at any time during the patient’s stay. Alternative methods of managing disturbed and violent patients were also recorded. The first 50 admissions occurred between 1 August and 17 September 1838.

Results

The demographic and clinical details of the first 50 patients admitted are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical details of the first 50 patients admitted to the Northampton Asylum

| Patient characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Gender: n (%) | |

| Male | 24 (48) |

| Female | 26 (52) |

| Age on admission: years | |

| Median | 38 |

| Range | 16-69 |

| Class of patient: n (%) | |

| Pauper | 46 (92) |

| Private | 4 (8) |

| Source of admission: n (%) | |

| Workhouse or another asylum | 34 (68) |

| Home address | 8 (16) |

| Infirmary (general hospital) | 2 (4) |

| Gaol | 1 (2) |

| Not stated | 5 (10) |

| Clinical details: n (%) | |

| History of violence towards others | 35 (70) |

| History of deliberate self-harm or attempted suicide | 11 (22) |

| Restrained in previous institution | 9 (18) |

| Admitted to Northampton Asylum in mechanical restraints | 8 (16) |

| Restraints removed on admission to Northampton Asylum | 7 (88) |

| Temporarily restrained while in Northampton Asylum | 4 (8) |

| Violent towards self or others while in Northampton Asylum | 15 (30) |

Case reports illustrating the adoption of non-restraint

J.C., a 31-year-old railroad labourer, was admitted as a pauper lunatic from a workhouse on 1 August 1838, with his first attack of insanity, having been ill for 2 months. The case notes record how he had assaulted his wife and bitten her severely:

‘After this he was restrained but escaped knocking down his keeper and scaling two high walls, he plunged into the canal and intentionally banged his head repeatedly with great violence against the bridge.’

The patient told Prichard that he had ‘worn a strait-waistcoat for more than a week’ prior to admission. Prichard wrote that no restraints were necessary but he ordered the patient be given a ‘low diet’, ‘ be kept quiet and cool’ and treated with digitalis, antimony tartrate and calomel. Two days after admission the patient asked to work in the garden and did so for more than an hour, ‘rather over exerting himself’. By 13 August he was working ‘daily in the garden from 9 in the morning until 6 pm’. The patient was discharged ‘ recovered’ 2 months after admission.

E.E., a servant aged 31 years, was admitted on 30 August 1838 as a private patient with her first attack of insanity. She had been treated at the local infirmary with bleeding and blisters, but had not improved. On admission to the Northampton Asylum, Prichard noted that she had ‘ulceration in the lumbar region and outer legs and ankles from being strapped to the bed’, as otherwise she was destructive of her clothing. No restraints were employed and the case notes record that she

‘continued in the state about a week during which time she was very bad destroying her bed continuously, tearing clothes to pieces and talking in a most incoherent manner to herself. [She was] treated with both shower baths and laxatives and bathing the head, under this other improved when tonic mixture was given and she rapidly recovered her reason.’

In February 1839 Prichard wrote, ‘this has been throughout a very interesting case’. ‘For the last fortnight she has filled the vacant post of a nurse’, and in March 1839 ‘having continued well since last report was this day discharged as a patient and engaged as a nurse’.

Case reports citing the use of restraint

M.E., a pauper lunatic aged 50 years, was transferred from the Bedford Asylum on 20 August 1838. She had been ‘afflicted 20 years’ and was ‘dirty, noisy and mischievous’. Three weeks after admission, Prichard wrote, ‘been obliged to keep the gloves on night and day to prevent her injuring herself or other patients’. A month later, he wrote that she ‘won’t part with her gloves and cries if they are taken away’, and then in February 1839 ‘no occasion for any restraint until the month of January when she became very excited, quarrelsome, noisy and destructive in which state she now remains’. There is no mention of the use of mechanical restraints.

J.S., a 25-year-old labourer and a pauper lunatic, was admitted on 24 August 1838 suffering from insanity caused by epilepsy. At the Bedford Asylum he was described as ‘very violent and malicious, will fight, kick and bite. Not to be trusted with any safety to the attendants’. However, to Prichard he seemed ‘perfectly sane in conversation and conduct’. He came in with ‘iron leg locks and handcuffs’. An entry dated 10 September records:

‘All restraint was removed on the night he was admitted.’ ‘ Has been once or twice under restraint, a mild character when suffering not the effects of a rapid succession of fits but even then they were not on longer than a few hours.’

Two subsequent entries state that no further use of restraint had been necessary and the patient was ‘very industrious and useful’.

The cases of J.S. and others are described by Prichard in his second annual report (Northampton Record Office, 1840), but the use of restraint in Northampton is not mentioned: ‘ they were taken out of restraint at bed time and have not been coerced for nearly two years’.

Discussion

Study of the early Northampton Asylum case notes suggests that Dr Prichard kept the use of restraints to a minimum. Only a minority of patients were brought to the asylum in mechanical restraints, but they were, as Prichard claimed, generally taken out of restraints on the night of admission, although in some instances temporary restraints were used subsequently to control violent behaviour. Prichard used solitary confinement, low rations and shower baths to control aggressive behaviour. An early textbook of psychiatry suggests that Prichard did, in rare cases, use restraint:

‘the late learned and excellent Dr Prichard, who perhaps more than any other English physician has adorned the psychological department of medicine and the great body of French, German and American practitioners, expressly recognised the necessity in exceptional cases of using mechanical restraint as a curative measure’ (Reference RobinsonRobinson, 1859: p. 217).

Case note documentation was poor by modern standards and the use of restraints may not always have been documented. After September 1838, the clinical records become extremely brief, with scarcely any entries subsequent to admission. Prichard was initially the sole asylum doctor and no doubt was kept extremely busy by the influx of pauper lunatics (nearly 200 in the first 2 years). In January 1839 Prichard’s cousin, also called Thomas Prichard, was appointed as his assistant but even after this date the notes do not improve. Unfortunately, the subsequent case ledger, which contained the medical notes of patients admitted during the rest of Prichard’s tenure at the Northampton Asylum, has been lost, and so no other documentation exists to corroborate his claim to have abolished mechanical restraints. Prichard resigned from the Asylum in June 1845 following allegations about his care of patients. He died in 1847 from cirrhosis of the liver. The assertion by Dr Prichard and the Committee of the Asylum to have completely abolished the use of mechanical restraints by October 1840, therefore, cannot be substantiated.

According to the records of the Lincoln Asylum, when the Northampton Asylum opened Prichard was unaware of Gardiner Hill’s experiment at Lincoln some 80 miles away (Lincolnshire Archives, 1841). The available evidence therefore suggests that the abolition of mechanical restraints was a gradual process that occurred at the same time in a number of different institutions and that no single individual can be identified as the unequivocal initiator of this movement in the UK. What perhaps can be said is that the Northampton Asylum was the first institution in the UK to advocate non-restraint as a philosophy from its opening.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Kerith Trick for sources of information about Dr Prichard.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.