Growing research links posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to a range of cardiometabolic conditions, including metabolic syndrome, heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes (Heppner et al. Reference Heppner, Crawford, Haji, Afari, Hauger, Dashevsky, Horn, Nunnink and Baker2009; Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Agnew-Blais, Spiegelman, Kubzansky, Mason, Galea, Hu, Rich-Edwards and Koenen2015; Sumner et al. Reference Sumner, Kubzansky, Elkind, Roberts, Agnew-Blais, Chen, Cerdá, Rexrode, Rich-Edwards, Spiegelman, Suglia, Rimm and Koenen2015; Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Bovin, Green, Mitchell, Stoop, Barretto, Jackson, Lee, Fang, Trachtenberg, Rosen, Keane and Marx2016; Koenen et al. Reference Koenen, Sumner, Gilsanz, Glymour, Ratanatharathorn, Rimm, Roberts, Winning and Kubzansky2017). A number of behavioral (e.g. poor diet, physical inactivity, cigarette smoking, substance use) and physiological (e.g. dysregulation of biological stress response systems, such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, autonomic nervous system, and immune system) pathways have been proposed to underlie associations between PTSD and cardiometabolic risk (Dedert et al. Reference Dedert, Calhoun, Watkins, Sherwood and Beckham2010; van Liempt et al. Reference van Liempt, Arends, Cluitmans, Westenberg, Kahn and Vermetten2013; Wentworth et al. Reference Wentworth, Stein, Redwine, Xue, Taub, Clopton, Nayak and Maisel2013; Koenen et al. Reference Koenen, Sumner, Gilsanz, Glymour, Ratanatharathorn, Rimm, Roberts, Winning and Kubzansky2017). Additionally, overlapping genetic factors may predispose individuals to both PTSD and cardiometabolic disease. Initial evidence for shared genetic effects across PTSD and cardiometabolic traits comes from studies based on twin designs (Vaccarino et al. Reference Vaccarino, Goldberg, Rooks, Shah, Veledar, Faber, Votaw, Forsberg and Bremner2013, Reference Vaccarino, Goldberg, Magruder, Forsberg, Friedman, Litz, Heagerty, Huang, Gleason and Smith2014) and candidate gene approaches (Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Shivakumar, Starr, Eidelman, Jacobowitz, Dalgard, Srivastava, Wilkerson, Stein and Ursano2016). However, to date, research has not examined the genetic overlap of PTSD and cardiometabolic disease using a genome-wide design.

Recent developments in genetic computational methods now permit the estimation of genetic correlations between complex traits from genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics, referred to as cross-trait LD score regression (LDSR) (Bulik-Sullivan et al. Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Anttila, Gusev, Day, Loh, Duncan, Perry, Patterson, Robinson, Daly, Price and Neale2015). This cross-trait LDSR approach can be applied flexibly by utilizing summary statistics as input (Bulik-Sullivan et al. Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Anttila, Gusev, Day, Loh, Duncan, Perry, Patterson, Robinson, Daly, Price and Neale2015). In contrast, other methods designed to identify shared genetic effects (i.e. polygenic scores and restricted maximum likelihood) require individual genotype data, which often cannot be released due to data-sharing restrictions. Another advantage of the LDSR method is that it is not biased by sample overlap across studies (Bulik-Sullivan et al. Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Anttila, Gusev, Day, Loh, Duncan, Perry, Patterson, Robinson, Daly, Price and Neale2015). The LDSR approach also incorporates the effects of all SNPs, including those that do not reach genome-wide significance, thereby improving the accuracy and power of genetic prediction (Dudbridge, Reference Dudbridge2016). However, one limitation of this method is that it can only be used with samples without recent admixture and for whom suitable large-scale genetic data resources are available. Given these restrictions, it can only be applied to European ancestry (EA) samples, and not African-American or Latino populations, at this time.

The Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC)-PTSD working group has been leading efforts to identify genetic risk variants associated with PTSD (Logue et al. Reference Logue, Amstadter, Baker, Duncan, Koenen, Liberzon, Miller, Morey, Nievergelt, Ressler, Smith, Smoller, Stein, Sumner and Uddin2015), and the first meta-analysis of PTSD GWASs (N = 20 070) has been recently completed by this group (Duncan et al. Reference Duncan, Ratanatharathorn, Aiello, Almli, Amstadter, Ashley-Koch, Baker, Beckham, Bierut, Bisson, Bradley, Chen, Dalvie, Farrer, Galea, Garrett, Gelernter, Guffanti, Hauser, Johnson, Kessler, Kimbrel, King, Koen, Kranzler, Logue, Maihofer, Martin, Miller, Morey, Nugent, Rice, Ripke, Roberts, Saccone, Smoller, Stein, Stein, Sumner, Uddin, Ursano, Wildman, Yehuda, Zhao, Daly, Liberzon, Ressler, Nievergelt and Koenen2017). In the present study, we used summary statistics from the PGC-PTSD meta-analysis of Duncan et al. (Reference Duncan, Ratanatharathorn, Aiello, Almli, Amstadter, Ashley-Koch, Baker, Beckham, Bierut, Bisson, Bradley, Chen, Dalvie, Farrer, Galea, Garrett, Gelernter, Guffanti, Hauser, Johnson, Kessler, Kimbrel, King, Koen, Kranzler, Logue, Maihofer, Martin, Miller, Morey, Nugent, Rice, Ripke, Roberts, Saccone, Smoller, Stein, Stein, Sumner, Uddin, Ursano, Wildman, Yehuda, Zhao, Daly, Liberzon, Ressler, Nievergelt and Koenen2017) to conduct the first GWAS-based investigation of potential genetic overlap between PTSD and cardiometabolic traits.

Methods

Cross-trait LDSR (Bulik-Sullivan et al. Reference Bulik-Sullivan, Finucane, Anttila, Gusev, Day, Loh, Duncan, Perry, Patterson, Robinson, Daly, Price and Neale2015) was used to estimate genetic correlations between PTSD and coronary artery disease (CAD), anthropometric traits [i.e. body mass index (BMI), waist circumference], glycemic traits [i.e. fasting glucose, fasting insulin, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C)], type 2 diabetes, and lipids [i.e. low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol, triglycerides]. These traits were selected because of their relevance to cardiometabolic disease, which has been robustly associated with PTSD, as described above (see Koenen et al. Reference Koenen, Sumner, Gilsanz, Glymour, Ratanatharathorn, Rimm, Roberts, Winning and Kubzansky2017, for a review). Analyses were conducted on LD Hub (Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Erzurumluoglu, Elsworth, Howe, Haycock, Hemani, Tansey, Laurin, Pourcain, Warrington, Finucane, Price, Bulik-Sullivan, Anttila, Paternoster, Gaunt, Evans and Neale2016), a centralized database of GWAS summary statistics that automates the LDSR pipeline (http://ldsc.broadinstitute.org/). The PGC-PTSD GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics used were based on 9542 EA participants (25% PTSD cases) that were collected across nine studies (see Duncan et al. Reference Duncan, Ratanatharathorn, Aiello, Almli, Amstadter, Ashley-Koch, Baker, Beckham, Bierut, Bisson, Bradley, Chen, Dalvie, Farrer, Galea, Garrett, Gelernter, Guffanti, Hauser, Johnson, Kessler, Kimbrel, King, Koen, Kranzler, Logue, Maihofer, Martin, Miller, Morey, Nugent, Rice, Ripke, Roberts, Saccone, Smoller, Stein, Stein, Sumner, Uddin, Ursano, Wildman, Yehuda, Zhao, Daly, Liberzon, Ressler, Nievergelt and Koenen2017, for study and sample details). These summary statistics were uploaded to LD Hub for genetic correlation with cardiometabolic traits. All cardiometabolic trait GWAS meta-analyses were based on predominantly EA ancestry samples (see Acknowledgements for GWAS study citations). In order to filter out rare or poorly imputed variants, we selected SNPs with a minor allele frequency >0.05 and an imputation information value >0.90. All procedures contributing to this work complied with ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Results

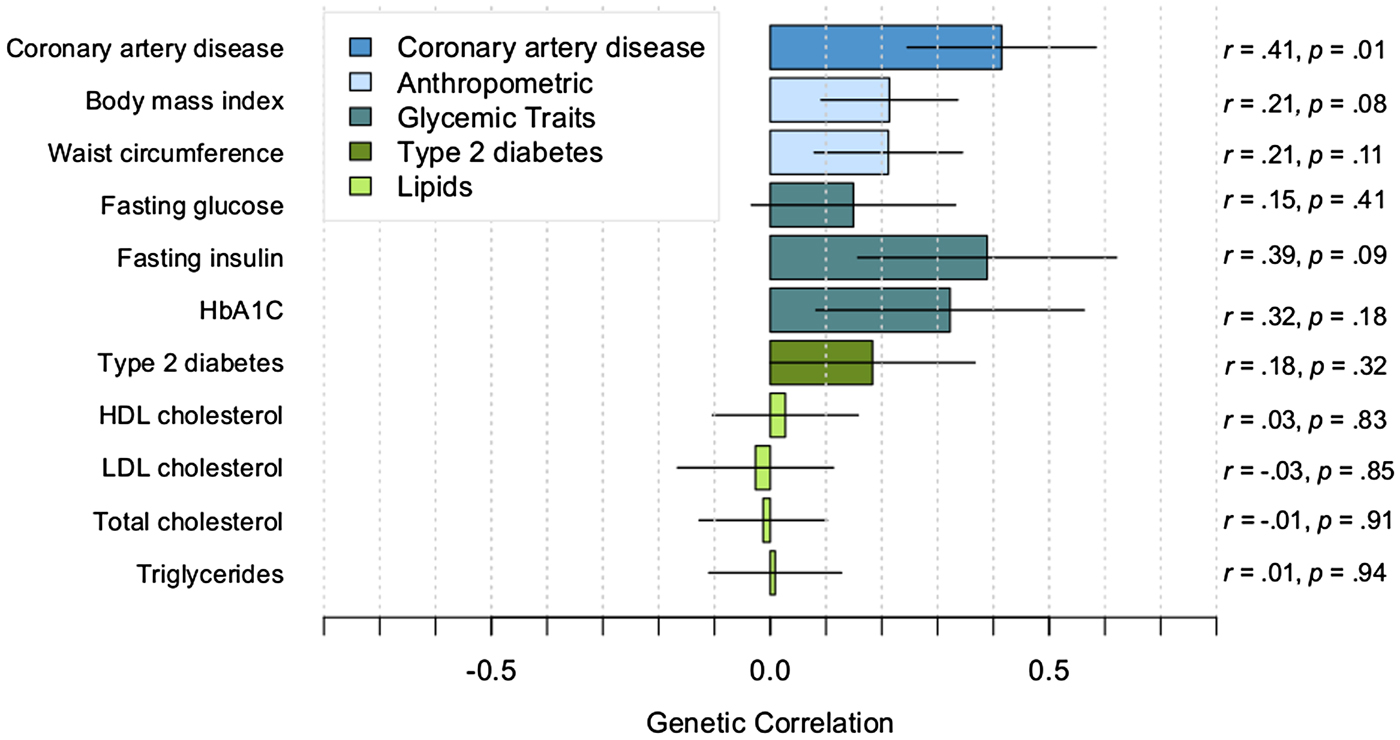

Small-to-moderate positive correlations were observed between PTSD with CAD, anthropometric traits, and glycemic traits (see Fig. 1 for correlations, s.e., and p values). The correlation of PTSD with CAD was significant (p = 0.01), and the correlations of PTSD with BMI and fasting insulin were nominally significant (p < 0.10). However, correlations did not survive correction for multiple testing based on either a Bonferroni correction (corrected p value threshold = 0.005) or a less stringent correction method (Li & Ji, Reference Li and Ji2005) for testing multiple correlated traits (corrected p value threshold = 0.006). As expected, the cardiometabolic traits had significant genetic correlations with each other. For example, correlations among the top cardiometabolic traits that were associated with PTSD were as follows: CAD–BMI, r = 0.22; CAD–fasting insulin, r = 0.27; BMI–fasting insulin, r = 0.57 (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 1. Genetic correlations between PTSD and cardiometabolic traits. Correlations estimated with cross-trait LDSR. Lines indicate s.e.

Discussion

We present the first-ever genetic correlations between PTSD and a range of cardiometabolic outcomes based on GWAS summary statistics. Findings suggested that, in EA individuals, there is potential for shared genetic contributions to PTSD and several cardiometabolic traits, including CAD, BMI, and fasting insulin. These results are indicative of shared genetic risk and consistent with epidemiologic evidence linking PTSD to elevated obesity, cardiovascular, and metabolic risk (Heppner et al. Reference Heppner, Crawford, Haji, Afari, Hauger, Dashevsky, Horn, Nunnink and Baker2009; Kubzansky et al. Reference Kubzansky, Bordelois, Jun, Roberts, Cerda, Bluestone and Koenen2014; Sumner et al. Reference Sumner, Kubzansky, Elkind, Roberts, Agnew-Blais, Chen, Cerdá, Rexrode, Rich-Edwards, Spiegelman, Suglia, Rimm and Koenen2015; Wolf et al. Reference Wolf, Bovin, Green, Mitchell, Stoop, Barretto, Jackson, Lee, Fang, Trachtenberg, Rosen, Keane and Marx2016). Importantly, the findings from the present research may also help to explain previously observed bidirectional associations between PTSD and cardiometabolic outcomes in the literature (Edmondson et al. Reference Edmondson, Richardson, Falzon, Davidson, Mills and Neria2012; Sumner et al. Reference Sumner, Kubzansky, Elkind, Roberts, Agnew-Blais, Chen, Cerdá, Rexrode, Rich-Edwards, Spiegelman, Suglia, Rimm and Koenen2015). Our findings are also consistent with twin and candidate gene research suggesting that there may be genetic linkage between PTSD, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes (Vaccarino et al. Reference Vaccarino, Goldberg, Rooks, Shah, Veledar, Faber, Votaw, Forsberg and Bremner2013, Reference Vaccarino, Goldberg, Magruder, Forsberg, Friedman, Litz, Heagerty, Huang, Gleason and Smith2014; Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Shivakumar, Starr, Eidelman, Jacobowitz, Dalgard, Srivastava, Wilkerson, Stein and Ursano2016). Although these are promising preliminary results, we note that cross-trait LDSR analyses do not address subgroup-specific effects (e.g. sex-specific effects), and these methods can only be currently applied to EA samples. Furthermore, even though our PTSD GWAS meta-analysis is the largest (and presumably best powered) to date, it was still underpowered to detect specific risk loci. Better-powered PTSD analyses in the future will also allow for better-powered genetic correlation analyses. Additionally, the current z-score for overall heritability of PTSD was 3 (Duncan et al. Reference Duncan, Ratanatharathorn, Aiello, Almli, Amstadter, Ashley-Koch, Baker, Beckham, Bierut, Bisson, Bradley, Chen, Dalvie, Farrer, Galea, Garrett, Gelernter, Guffanti, Hauser, Johnson, Kessler, Kimbrel, King, Koen, Kranzler, Logue, Maihofer, Martin, Miller, Morey, Nugent, Rice, Ripke, Roberts, Saccone, Smoller, Stein, Stein, Sumner, Uddin, Ursano, Wildman, Yehuda, Zhao, Daly, Liberzon, Ressler, Nievergelt and Koenen2017), and a heritability z-score >4 has been recommended for testing multiple genetic correlation estimates (Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Erzurumluoglu, Elsworth, Howe, Haycock, Hemani, Tansey, Laurin, Pourcain, Warrington, Finucane, Price, Bulik-Sullivan, Anttila, Paternoster, Gaunt, Evans and Neale2016). We will continue to explore these associations as the PGC-PTSD grows and incorporates more samples in future meta-analyses. Nonetheless, we believe that these results provide initial support that the growing number of associations of PTSD and cardiometabolic diseases reported in the literature may be due, in part, to shared genetic contributions.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following GWASs that contributed data to the current study: PTSD (PGC-PTSD; Duncan et al. Reference Duncan, Ratanatharathorn, Aiello, Almli, Amstadter, Ashley-Koch, Baker, Beckham, Bierut, Bisson, Bradley, Chen, Dalvie, Farrer, Galea, Garrett, Gelernter, Guffanti, Hauser, Johnson, Kessler, Kimbrel, King, Koen, Kranzler, Logue, Maihofer, Martin, Miller, Morey, Nugent, Rice, Ripke, Roberts, Saccone, Smoller, Stein, Stein, Sumner, Uddin, Ursano, Wildman, Yehuda, Zhao, Daly, Liberzon, Ressler, Nievergelt and Koenen2017); CAD (CARDIoGRAM; PMID 26343387); type 2 diabetes (DIAGRAM; PMID 22885922); BMI (GIANT; PMID 20935630); waist circumference (GIANT; PMID 25673412); fasting glucose and insulin (MAGIC; PMID 22581228); HbA1C (MAGIC; PMID 20858683); LDL, HDL, and total cholesterol and triglycerides (GLGC; PMID 20686565). They also acknowledge Jie Zheng for his assistance with LD Hub. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (J.A.S., K01HL130650), (C.N., R01MH106595), (E.J.W., R03AG051877), (A.B.A., K02AA023239); and the United States (US) Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences R&D (CSRD) Service (E.J.W., Merit Review Award Number I01 CX-001276-01).

Declaration of Interest

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or the US Government.