College is often an experience of new-found autonomy for many students, resulting in lifestyle behaviours changes(Reference Owens, Christian and Polivka1,Reference Pancer, Hunsberger and Pratt2) and increases in poor mental health for incoming students(Reference Ghrouz, Noohu and Manzar3). Poor mental and physical health can impact college students’ success through poor academic performance and high attrition rates(Reference Taras4,Reference Calicchia and Graham5,Reference Beauchemin, Gibbs and Granello6,Reference Bruffaerts, Mortier and Kiekens7) . Regarding student well-being, sleep is often impacted upon entering college(Reference Pilcher, Ginter and Sadowsky8), where between 40 and 65 % of US college students meet the cut-off criteria for poor sleep when measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a validated tool that measures dimensions of sleep quality including duration and continuity(Reference Becker, Jarrett and Luebbe9). This change in sleep quality is often attributed to increased social and academic demands that may result in less or disrupted sleep(Reference Pilcher, Ginter and Sadowsky8,Reference Famodu, Barr and Holásková10) , although college students are also at risk for sleep disorders such as Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS).(Reference Gaultney11) Poor sleep quality is a common symptom of many mental health disorders(Reference Ghrouz, Noohu and Manzar3,Reference Nagata, Palar and Gooding12) , including depression and anxiety(Reference Pilcher, Ginter and Sadowsky8,Reference Lund, Reider and Whiting13) , and can lead to poor physical health as well(Reference Lund, Reider and Whiting13). Further, lack of quality sleep can interfere with college students’ academic achievement(Reference Gaultney11). Thus, maintaining positive mental and physical well-being with quality sleep in college is essential for student success.

In addition, student well-being can be influenced by experiencing food insecurity, defined as having limited or uncertain access to or availability of safe and nutritious food(14). College food insecurity has also been associated with decreased success in academia(Reference Hagedorn, McArthur and Hood15), making it an area of concern as university administrators seek to improve student retention. Research has emerged in the past decade on the heightened prevalence of food insecurity on college campuses with a recent scoping review reporting a 41 % prevalence rate from peer-reviewed studies, based on weighted means and sample sizes of studies(Reference Nikolaus, An and Ellison16). Some evidence suggests that there is a two-way relationship between food security and mental and physical health. Individuals who have poor mental and physical health may be at increased risk for food insecurity due to difficulties with sustained employment and income or lack of financial management(Reference Lent, Petrovic and Swanson17). At the same time, specifically among college students, being food insecure has been shown to increase the risk of mental health disorders(Reference Bruening, Brennhofer and van Woerden18) and be associated with self-reported poor health outcomes(Reference Hagedorn, McArthur and Hood15). Further, food insecurity is associated with poor sleep outcomes including longer sleep latency and shorter sleep duration(Reference Nagata, Palar and Gooding12,Reference Ding, Keiley and Garza19) , although much of this previous research has been limited to the young adult population as a whole.

To our knowledge, researchers in three studies have begun to explore the relationship between food insecurity and sleep among college students, all reporting that food insecurity is related to poor sleep among college students, although the methods used to measure food insecurity and sleep quality vary in these studies as well as the sample size(Reference Martinez, Grandner and Nazmi20,Reference El Zein, Shelnutt and Colby21,Reference Becerra, Bol and Granados22) . El Zein and colleagues (2019) used validated tools and captured data from multiple institutions; however, this research only targeted first-year students(Reference El Zein, Shelnutt and Colby21), thus excluding student populations that are typically more at risk for food insecurity(Reference Hagedorn, McArthur and Hood15). The objective of this study was to explore the association between food insecurity, perceived mental and physical well-being, and sleep quality among college students across twenty-two colleges and universities. We hypothesised that food insecurity would be associated with a greater risk of poor sleep quality and increased days with mental and physical health issues.

Methods

Participants and procedures

In the fall of 2019, a cross-sectional, online survey was distributed to college students across twenty-two colleges and universities in the US and territories. The twenty-two colleges and universities that participated were part of a previous food insecurity working group(Reference Hagedorn, McArthur and Hood15), with additional partners recruited at the 2019 Southeastern University Consortium On Hunger, Poverty And Nutrition conference and through peer networks. All colleges and universities that had a principal investigator interested were able to participate. The twenty-two institutions were located in twelve states: Alabama, Arizona, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia.

Institutional Review Board approval was granted at the lead university (approval no. 1904527720A003) and covered all participating institutions. College students had to be enrolled at a participating university or college at the time of the study and at least 18 years old to participate. There was no cut-off for age. Online consent was required before college students could access the online Qualtrics survey (Qualtrics). College students were recruited via email through campus listservs direct to students or email to departmental contacts on campus to forward to students. Two universities offered no incentive for participation, but the remaining institutions offered either a drawing or random selection for a limited number of gift cards or course extra credit. The recruitment email included a link to the online Qualtrics survey and took college students an estimated 30 min to complete. The survey contained 122 questions and was developed by the authors through modification of previously used food insecurity surveys(Reference Hagedorn, McArthur and Hood15,Reference McArthur, Ball and Danek23,Reference Hagedorn and Olfert24) and guided by college food insecurity literature, including the Government Accountability Office report on college hunger(25). Only variables related to sleep and mental and physical health were included in this analysis.

Measures

Food security status

Food-insecure students were identified using the United States Department of Agriculture Adult Food Security Survey(26), as used in previous college food insecurity literature(Reference Hagedorn, McArthur and Hood15,Reference McArthur, Ball and Danek23,Reference Soldavini, Berner and Da Silva27) . This validated ten-item survey tool asked students to respond affirmatively or non-affirmatively to statements measuring several characteristics of food insecurity, including the inability to acquire food for financial reasons, concern over obtaining food, and reduced quality and quantity of food consumed. The phrasing was modified from the original United States Department of Agriculture tool which assesses food insecurity ‘in the last 12 months’ to ‘since being in college’ to ensure questions were focused on campus issues instead of when students may have lived at home with a parent or guardian as a minor(Reference McArthur, Fasczewski and Wartinger28). Using the United States Department of Agriculture protocol(Reference Bickel, Nord and Price29), students were categorised into high (0 affirmative responses), marginal (1–2 affirmative responses), low (3–5 affirmative responses) and very low food security (6–10 affirmative responses) categories. Students were further dichotomised as food secure (high and marginal food security) and food insecure (low and very low food security).

Sleep quality

The PSQI, a nineteen-item, validated questionnaire, was used to measure sleep quality over the past month(Reference Buysse, Reynolds and Monk30,Reference Dietch, Taylor and Sethi31) and has been implemented previously among college students(Reference Lund, Reider and Whiting13,Reference El Zein, Shelnutt and Colby21,Reference Vargas, Flores and Robles32) . The first four questions asked students to report the time they went to bed (not necessarily the time they fell asleep), the number of minutes it took to fall asleep, when they awoke and hours of sleep per night. The next ten questions asked how often the participant had trouble sleeping because of reasons such as having to get up to use the restroom, feeling too hot or too cold, having pain, or waking up in the middle of the night, with questions answered on a four-point scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘three times or more a week.’ Students also rated on the same four-point scale their use of medication to fall asleep, how often they have trouble staying awake during social activity and if enthusiasm has been lacking to complete tasks. Last, students provided a subjective rating of their sleep quality on a four-point scale from ‘very good’ to ‘very bad.’ The PSQI questions were combined into seven different scores ranging from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty) on topics of sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, sleep medication and daytime dysfunction per the PSQI scoring guidelines(Reference Buysse, Reynolds and Monk30). The seven component scores were summed for a final PSQI score that ranged from 0 to 21, with sleep quality declining with each increase in the score(Reference Buysse, Reynolds and Monk30). PSQI scores >5 are indicative of poor sleep quality(Reference Buysse, Reynolds and Monk30).

Physical and mental health

Three items from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s four-item Healthy Days Core Module, a component of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Health-Related Quality of Life measure, were used(Reference Hennessy, Moriarty and Zack33,34) . The three items from the Healthy Days Core Module asked the students about the number of days in the past 30 d they have experienced particular health-related conditions or problems. The first and second questions assessed the number of impaired physical or mental health days in the past month, and the third assessed limitations in usual activities due to poor physical or mental health. All questions were scored between 0 and 30 d with higher days indicating more occurrence of poor mental or physical health.

Covariates

University attended, age, sex and race of participants were self-reported. Height and weight were self-reported and used to calculate BMI. Information on whether a student lived on or off campus, had dependents and had a disability were collected due to their relationships with food insecurity(25). Last, students completed questions regarding RLS due to the relationship with sleep quality(Reference Gaultney11) and mental and physical health(Reference Zhuang, Na and Winkelman35,Reference Kushida, Martin and Nikam36) . The 2003 criteria for the diagnosis of RLS from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group were used(Reference Allen, Picchietti and Hening37). Per these criteria, students responded to five questions to assess four criteria of RLS(Reference Sunwoo, Kim and Chu38). The first criterion composed of two questions asking: ‘Do you have, or have you had, recurrent uncomfortable feelings or sensations in your legs while you are sitting or lying down?’ and ‘Do you, or have you had, a recurrent need or urge to move your legs while you are sitting or lying down?’ A ‘yes’ response to both questions was required for RLS affirmation in the first criterion. The second criterion asked, ‘Are you more likely to have these feelings when you are resting (either sitting or lying down) or when you are physically active?’ with a ‘resting’ response required for RLS affirmation. The third criterion asked, ‘If you get up or move around when you have these feelings, do these feelings get any better while you actually keep moving?’ to which a participant responded ‘yes’ for RLS affirmation. Last, respondents who answered ‘evening’ and/or ‘night’ to the question ‘At which times of day are these feelings in your legs most likely to occur?’ were considered to meet the fourth criterion. Participants were considered to have symptoms of RLS if they responded affirmatively to all four criteria, creating a dichotomised variable of positive or negative for RLS symptoms.

Analysis

Sample size at each university is shown in Table 1. Only respondents that completed the full Adult Food Security Survey, PSQI and Healthy Days Core Module questions were included in the study and combined across universities for the analytical sample (n 17 686). Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages; these were compared by food security status using the Pearson’s χ 2 test and Cramer’s V for effect size. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation; these were compared by food security status using the Wilcoxon test and Pearson’s r for effect size. The PSQI and physical and mental health variables were entered into a logistic regression model to identify independent factors for food insecurity. A second model was conducted with the covariates university, age, sex, race, BMI, living on or off campus, having dependents, having a disability and having RLS symptoms added to calculate adjusted OR (AOR) (n 16 793). A sensitivity analysis was conducted using a third model that included only freshman level students and controlled for the aforementioned covariates from the second model (n 3098). Goodness of fit was assessed and showed the likelihood ratio tests for all models at P < 0·0001, indicating good model fit for all models. Statistical significance was deemed at P < 0·004 using Bonferroni correction. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro version 12.2 (SAS Institute Inc.) and SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc.).

Table 1 Sample from participating universities

Results

The analytical sample (n 17 686) is described in Table 2. Students were predominantly white (83·5 %) and female (74·8 %), with an average 8·1 (9·0)/30 d of poor mental health, 3·2 (5·7)/30 d of poor physical health and 3·9 (6·3)/30 d when their physical or mental health interfered with completing daily tasks. Mean age was 22·4 (5·5) years and mean BMI was 24·7 (5·5). Most students lived off campus (66·9 %), had no dependents (92·4 %), no disabilities (92·0 %) and no RLS symptoms (94·1 %). Students’ mean PSQI score was 7·2 (3·5) indicating poor sleep quality. Many (43·4 %) college students were food insecure. In univariate analysis, food insecurity status was associated with being Black or mixed race (χ 2 = 215·17, P < 0·0001), living off campus (χ 2 = 159·87, P < 0·0001), having a self-reported disability (χ 2 = 178·26, P < 0·0001) and having RLS symptoms (χ 2 = 63·56, P < 0·0001). Students who were food insecure had higher PSQI scores (t = 40·20, P < 0·0001) and a higher number of days with poor mental health (t = 37·62, P < 0·0001), physical health (t = 19·72, P < 0·0001) and days in which their mental and physical health interfered with their daily activities (t = 35·33, P < 0·0001).

Table 2 Characteristics of college student participants and correlation with food security status

PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; HDCM, Healthy Days Core Module.

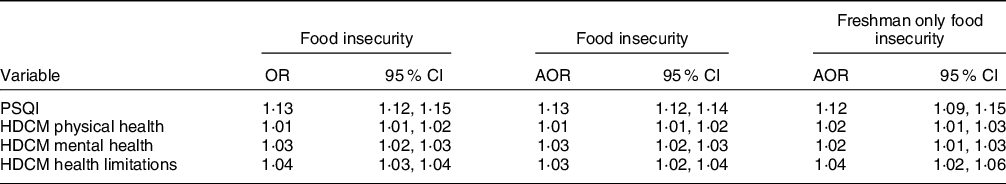

OR and AOR, controlling for covariates, from the logistic regression models are shown in Table 3. When controlling for covariates, being food insecure was associated with higher PSQI scores (AOR: 1·13; 95 % CI 1·12, 1·14), and increased days with poor physical health (AOR: 1·01; 95 % CI 1·01, 1·02) and mental health (AOR: 1·03; 95 % CI 1·02, 1·03). Experiencing food insecurity was also associated with more days where students’ mental or physical health limited their ability to complete daily tasks (AOR: 1·03; 95 % CI 1·02, 1·04). The sensitivity analysis model containing only freshman is also shown in Table 3.

Table 3 Food insecurity odds in relationship with sleep quality, physical health and mental health (n 17 686)*,†

AOR, adjusted OR; PSQI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index; HDCM, Healthy Days Core Module.

* AOR model controls for university, age, sex, race, BMI, living on or off campus, having dependents, having a disability and having restless leg syndrome symptoms (n 16 560).

† Freshman only AOR model includes only freshman level students and controls for controls for university, age, sex, race, BMI, living on or off campus, having dependents, having a disability and having restless leg syndrome symptoms (n 3098).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between food insecurity, sleep quality, and mental and physical health among college students using a multi-campus approach. As hypothesised, food insecurity among college students was associated with worse sleep quality, while food security among the respondents was associated with higher sleep quality. Food insecurity was also associated with an increased number of days with poor mental and physical health and has these health consequences impact completing tasks. These results highlight the impact food insecurity may have on the daily functioning of students, influencing their health and well-being outcomes.

Sleep quality among college students is reportedly low(Reference Becker, Jarrett and Luebbe9). The student population used within this study aligns with these previous findings as the analytical sample has an average PSQI score of 7·2, indicating the population as a whole had poor sleep quality(Reference Buysse, Reynolds and Monk30). The reasoning for poor sleep quality among college students was explored in a 2010 study by Lund and colleagues that reported emotional and physical stress were predictors of poor quality sleep(Reference Lund, Reider and Whiting13). However, food insecurity was not included as a potential explanation. Our study finds that food-insecure students reported a higher prevalence of RLS, a common deterrent of adequate sleep quality, and overall poorer sleep as indicated by higher PSQI scores among food-insecure students. Controlling for RLS, food insecurity was associated with worsened PSQI scores, indicating that food insecurity may be an important factor influencing students’ overall sleep quality. Becerra and colleagues report that components of food insecurity are a social determinant of sleep health specifically influencing daytime sleepiness and breathing issues during sleep(Reference Becerra, Bol and Granados22). This relationship between food insecurity and poor sleep health was attributed to potential disruptions in glycaemic control resulting in low energy, circadian rhythm disruption and weight issues causing snoring or sleep apnoea(Reference Becerra, Bol and Granados22). More research is needed to understand the mechanisms between food insecurity and overall poor sleep quality among college students.

In a similar study, El Zein et al. reported that food-insecure students were 132 % more likely to have poor sleep quality(Reference El Zein, Shelnutt and Colby21). These odds are higher than that reported in this current study, which may have been attributed to the first-year student population assessed. However, sensitivity analysis showed little difference between freshman and the full study population. Therefore, these results may be explained by the Time Preference Theory as explored by Knol and colleges (2017) when seeking to understand food insecurity and poor health outcomes(Reference Knol, Robb and McKinley39). Using this theory, college students with higher time preference, referring to an individual who selects short-term rewards instead of long-term rewards that can impact future health outcomes, may be neglecting their sleep habits to reap the benefit of good grades without consideration of the long-term impact(Reference Brown and Biosca40). As poor sleep can lead to academic consequences among college students(Reference Hershner and Chervin41,Reference Trockel, Barnes and Egget42) , higher education administration must promote healthy sleep programming on campus. Further, poor sleep quality can influence the development of chronic disease that can impact college students throughout their lifespan(Reference Altman, Izci-Balserak and Schopfer43,Reference Gray, Lee and Sesso44) . Specifically, Martinez and colleagues found that food insecurity reported fewer days with enough sleep which was related to higher weight and poor health outcomes among college students(Reference Martinez, Grandner and Nazmi20), making it imperative to improve sleep quality where possible. Previous research has shown that campus-based sleep campaigns may help students improve their sleep quality(Reference Orzech, Salafsky and Hamilton45), although, without the alleviation of food insecurity, these programmes might lack effectiveness.

This study also demonstrates a small but statistically significant correlation between the occurrence of poor mental and physical health days and food insecurity among college students. Previously, college students who were classified as food insecure have been classified as more likely to report their health as fair or poor(Reference Hagedorn, McArthur and Hood15). Mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety, have also been previously associated with college food insecurity. For example, Wattick, Hagedorn and Olfert found that college students suffered from mental health issues for roughly a third of the month, and the likelihood of having depressive or anxious symptoms was increased among students who were food insecure(Reference Wattick, Hagedorn and Olfert46). There is likely a two-way relationship between food insecurity and poorer mental and physical health. Food insecurity may contribute to poor mental health due to increased stress experienced by food-insecure individuals(Reference Martin, Maddocks and Chen47) or stigmatisation they face(Reference Palar, Frongillo and Escobar48). The poorer dietary quality shown among food-insecure populations could also contribute to nutritional deficits that serve as a barrier to healthy functioning, both mental and physical(Reference Wattick, Hagedorn and Olfert46). Poor mental and physical health can also contribute to sleep disturbances and lowered productivity(Reference Rosekind, Gregory and Mallis49). Thus, food insecurity, mental and physical health, and sleep quality may be a bidirectional cyclic process. In turn, declines in daily functioning overall could lead to an increased economic burden on food-insecure individuals(Reference Greenberg, Fournier and Sisitsky50,Reference Druss, Marcus and Olfson51) .

As food-insecure populations often face financial limitations(Reference Gaines, Robb and Knol52), the additional financial hardship caused by days with poor mental and physical health may inhibit food-insecure individuals from overcoming the barriers they face. Thus, due to the potential bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and poor mental and physical health, a holistic approach is needed on college campuses to promote the health of the mind and body. Further, in light of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, special attention may be needed for students who face financial burdens as a result of the pandemic. Reports on food insecurity highlight an increased prevalence since the pandemic(Reference Niles, Bertmann and Belarmino53), and college students are reported to have increased poor mental health(Reference Cao, Fang and Hou54) with decreased access to assistance during the pandemic(Reference Lee55); thus, higher education administrators should continue to provide and advocate for outreach and support to students in need(Reference Zhai and Du56).

This study used the largest sample of college students to date to further strengthen the knowledge of the association between food insecurity, mental and physical health, and sleep. College students from twenty-two higher education institutions were represented, thus highlighting students from diverse universities and regions. However, this study is not without limitations. First, the effect size of the OR is small although significant. The non-probability sample may contain a degree of selection bias, and the cross-sectional study design limits the ability to distinguish causation. Self-response bias may have occurred due to the self-reporting of measures. Further, the sample is predominately white and female; thus, future research needs to target male and minority populations to expand the understanding of this issue in all college populations. The validity of the United States Department of Agriculture food security tools when used with college students has been questioned(Reference Nikolaus, Ellison and Nickols-Richardson57), as well as the modality of measurement(Reference Nikolaus, Ellison and Nickols-Richardson58), and thus may cause error in the food insecurity measurement. However, the ten-item Adult Food Security Survey used in this study has been reported to have the best fit among college students(Reference Nikolaus, Ellison and Nickols-Richardson59). Further, the PSQI and the Healthy Days Core Module were measured on a time frame looking at the past 30 d, whereas the Adult Food Security Survey assessed since students began college which may impact results as food insecurity can be episodic in nature. Therefore, future research should seek to assess these variables using the same time frame to ensure students are reporting occurrence of each variable simultaneously.

Food insecurity is a current public health problem facing college students in the US, with this study reporting a 43·4 % prevalence rate among college students at twenty-two higher education institutions. These food-insecure students report declined sleep quality and mental and physical health which could impact their success in college as well as their overall health in the long term. Thus, college and university wellness programmes should aim to support food-insecure students as a means of improving the mental and physical well-being of students and inform the need for holistic programming that considers multiple aspects of college student well-being and health. Further, these results can be used by advocates for college food security to show policymakers the layers of impact food insecurity may have on college students’ welfare.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: Not applicable. Financial support: Primary funding is from the West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station WVA00689 and WVA00721. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: Conceptualisation was led by R.L.H. and M.D.O. Survey develop was led by R.L.H. and M.D.O. with input from all authors. Data collection lead by R.L.H. and M.D.O., with all authors leading collection at their respective university. Data cleaning and analysis lead by R.L.H. The manuscript was drafted by R.L.H. All authors provided edits and have approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the West Virginia University Institutional Review Board. Online written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.