Women who gain too much or too little weight during pregnancy are more likely to experience a variety of health problems during their pregnancies and in their later lives. Healthy gestational weight gain (GWG) yields the best obstetric outcomes and improves the long-term outcomes for the health and weight of mothers and their babies( Reference Rasmussen and Yaktine 1 ).

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published revised guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy, providing recommendations for GWG based on a woman’s pre-pregnancy BMI. According to these guidelines, women who begin their pregnancy being underweight (BMI less than 18·5 kg/m2) should gain 12·5–18·0 kg during their pregnancy; normal weight women (BMI of 18·5–24·9 kg/m2) should gain 11·5–16·0 kg; women who are overweight (BMI of 25·0–29·9 kg/m2) should gain 7–11·5 kg; and obese women (BMI of 30·0 kg/m2 or above) should gain 5–9 kg( Reference Rasmussen and Yaktine 1 ). The percentage of women in high-income countries who gain weight within these recommendations varies from 18·9 to 51·9 %( Reference Rauh, Gabriel and Kerschbaum 2 – Reference Daemers, Wijnen and van Limbeek 4 ), demonstrating a clear need to focus on healthy GWG to improve the health prospects of mothers and babies.

Several interventions for promoting healthy GWG have been studied( Reference Campbell, Johnson and Messina 5 – Reference Thangaratinam, Rogozinska and Jolly 14 ). Reviews of these studies show these interventions to have varied effects, depending in large part on their target group (i.e. a general population or a specific risk group). The majority of GWG studies target specific groups, such as overweight or obese women, or women with hypertension or gestational diabetes. Interventions adopting a dietary approach, increasing physical activity and setting weight gain goals proved to be most effective at reaching healthy GWG( Reference Thangaratinam, Rogozinska and Jolly 14 ).

Interventions to encourage appropriate GWG fit well with the midwifery model of care( Reference Renfrew, McFadden and Bastos 15 ). A recent review of midwifery in the UK underscored the relationship between public health and midwifery( 16 ), emphasizing the importance of public health interventions during pregnancy and the postnatal period. Community midwives are in a unique position to improve the health of young families because they have regular contact (about twelve times) with pregnant women. In the Netherlands, 85 % of pregnant women begin care with community midwives and more than 50 % continue their pregnancy under guidance of the midwife( 17 ). Community midwives are authorized to care for healthy pregnant women, a group that stands to benefit from the prevention of weight-related disorders.

The theoretical and methodological tools used in health psychology can increase the effectiveness of health-related interventions( Reference Gardner, Wardle and Poston 9 , Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 , Reference Merkx 19 ). However, as Hill et al. found in their review, it is very difficult to identify the theoretical assumptions of existing interventions designed to promote healthy GWG( Reference Hill, Skouteris and Fuller-Tyszkiewicz 10 ). In the present paper we provide insights into the theoretical assumptions used in GWG interventions by describing the development of our ‘Come On!’ intervention promoting healthy GWG among healthy pregnant women. Our use of intervention mapping, a systematic approach for the development of interventions based on established theory and empirical data, makes explicit the theories we used to design our programme( Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 ). Intervention mapping also recognizes that individual behaviour is influenced by factors in the environment, namely individual, family, social network, organizations, communities and society( Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 ).

Methods

Intervention mapping consists of six steps: (i) needs assessment; (ii) formulation of change objectives; (iii) selection of theory-based methods and practical strategies; (iv) development of the intervention programme; (v) development of an adoption and implementation plan; and (vi) development of an evaluation plan. Here we describe the consecutive steps and will apply them in the Results section.

Step I: Needs assessment

Intervention mapping starts with the identification of the health problem, its behavioural factors and their associated individual and environmental determinants. The aim of this first step is to establish the relevant target groups and programme outcomes.

In our case, the needs assessment included a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature on existing interventions for achieving a healthy GWG( Reference Merkx 19 ). We also analysed the literature on the determinants and correlates of GWG in pregnant women, including the role of predefined behavioural (i.e. physical activity and dietary behaviour) and environmental risk factors.

In addition, we conducted a quantitative survey among healthy pregnant woman to investigate the percentages of women reaching healthy GWG and to assess the relationship between, among other factors, diet and physical activity and reaching a healthy GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ). Furthermore, we scheduled individual interviews with community midwives to identify their behaviours with respect to promoting healthy GWG and the determinants of their behaviours( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 21 ). The interview protocol was based on the Attitude–Social Influence–Self-Efficacy model( Reference Brug, Oenema and Ferreira 22 ), a model useful in explaining or changing a variety of behaviours( Reference Noar, Crosby and Benac 23 , Reference Temel, Birnie and Sonneveld 24 ). We used the information from the interviews and literature to construct our study model and questionnaire for the quantitative survey to measure midwives’ self-reported behaviours and determinants( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ).

During the needs assessment we established a project consortium including several midwives practising in primary care, a dietitian, a physiotherapist, a psychologist working with young mothers, an employee of the Royal Dutch Organization of Midwives (KNOV) and health educators. During the needs assessment, the project team met three times, to discuss the research findings, contribute to the decision-making process on the selection of target groups and advise on the outcomes of the behavioural programme. Between the meetings, we consulted with individual project members as needed.

Step II: Formulation of change objectives

In this second intervention mapping step, programme outcomes were subdivided into performance objectives. Performance objectives are related to sub-behaviours that must be accomplished by the target groups in order to achieve the programme outcomes. By linking the performance objectives with relevant behavioural determinants, the general formulations of the performance objectives were translated into very specific change objectives. The consortium was also involved in step II. Members offered advice about the relevance and changeability of the selected behavioural determinants and approved the formulation and selection of change objectives.

Step III: Selection of theory-based methods and practical strategies

In step III we identified and selected the theoretical methods; that is, general techniques or processes for influencing changes in behavioural determinants of the target groups. To do so, the change objectives were organized per determinant. Subsequently, methods were matched to the determinants. Methods were mainly selected from the summary of theoretical methods provided by Bartholomew et al.( Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 ). We organized a brainstorming session with the consortium in order to select the practical strategies to be used, identifying the specific techniques for employing theoretical methods in ways that fit our intervention population and the context in which our intervention would be conducted. We also relied on our systematic literature review of existing interventions for information on feasible working mechanisms( Reference Merkx 19 ).

Step IV: Development of the intervention programme

In step IV we combined information from previous steps, which allowed us to operationalize the theoretical methods and develop the practical applications required to accomplish the change objectives. We decided upon programme scope and sequence and designed scripts and documents needed for the production of the programme. During this process we pre-tested our materials among members of the target groups, including consortium members and pregnant women.

Step V: Development of an adoption and implementation plan

The fifth step focused on the planning of the adoption and implementation of the intervention. The consortium meetings provided important information about the factors that would impede and enhance implementation in midwifery practices.

Step VI: Development of an evaluation plan

In this last step we developed a plan to evaluate the programme effectiveness and the quality of intervention. Our measurement instruments for evaluating programme effects were based on the instruments used in the needs assessment (step I) and on instruments for process evaluation described by Steckler and Linnan( Reference Steckler and Linnan 26 ).

Results

Step I: Needs assessment

In the literature, unhealthy GWG is described as both serious and widespread. The majority of published studies have focused on risk groups, such as obese pregnant women. As noted above, the percentage of women in high-income countries who gain weight within the IOM guidelines varies from 18·9 to 51·9 %( Reference Rauh, Gabriel and Kerschbaum 2 , Reference Hunt, Alanis and Johnson 3 , Reference Hector and Hebden 27 ). In the Netherlands at the time of the study, the incidence of women who gained weight below, within and above the IOM guidelines was respectively 18·8–33·4 %, 39·9–43·8 % and 26·7–37·6 %( Reference Daemers, Wijnen and van Limbeek 4 , Reference Althuizen, van Poppel and Seidell 28 ). For neonates, GWG below the guidelines was associated with prematurity and babies too small for their gestational age( Reference Yu, Han and Zhu 29 ). GWG above the guidelines was associated with, among other things, low 5-min Apgar scores, seizures, hypoglycaemia, polycythaemia, meconium aspiration syndrome and large for gestational age( Reference Muktabhant, Lumbiganon and Ngamjarus 11 ). For women, GWG above the guidelines was associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-eclampsia, caesarean delivery, postpartum weight retention and long-term obesity( Reference Muktabhant, Lumbiganon and Ngamjarus 11 , Reference Zamora-Kapoor and Walker 30 ). A number of studies found that diet and physical activity are not the only mediators of healthy GWG( Reference Phelan, Jankovitz and Hagobian 31 , Reference Streuling, Beyerlein and von Kries 32 ): the behaviour of health professionals also plays an important role( Reference Olander, Atkinson and Edmunds 33 , Reference Stengel, Kraschnewski and Hwang 34 ). Midwives, as the providers of regular check-ups during pregnancy, are important players in the process of reaching healthy GWG.

Our cross-sectional survey among 455 healthy Dutch pregnant women showed that GWG within the guidelines occurred in 42·4 % of the women, 13·8 % of the women gained too little and 43·9 % too much( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ). There was no significant correlation between GWG and pre-pregnancy BMI, diet or motivation to engage in healthy PA( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ). Weight gain below the IOM guidelines, v. within, was seen more often in women who reported more sleep shortage. Weight gain above the IOM guidelines (v. within) was seen less often in Dutch than in non-Dutch women, in women who maintained their physical activity level and in non-smoking women compared with women who stopped smoking( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ). The mean weekly vegetable consumption was 953 (sd 447) g. Recommended intake of vegetables, fruit and fish (respectively: ≥200 g/d; ≥2 pieces/d; ≥twice during the last week) was met by respectively 13·6, 47·2 and 6·8 %( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ). Nevertheless, the dietary behaviour of our sample was better than that of non-pregnant women of comparable ages in the Netherlands( Reference Van Rossum, Fransen and Verkaik-Kloosterman 35 ), indicating that pregnant women do improve their diet during pregnancy. However, none of the measured dietary behaviours were significantly associated with healthy GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ). More than half of the women reported a decline in physical activity during pregnancy and the self-reported mean pre-pregnancy physical activity was moderately active. A decline in physical activity was associated with GWG above the guidelines( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ).

Our qualitative study of six community midwives showed that midwives did monitor GWG (weighing and discussing GWG), offer education about diet and, to a lesser degree, offer education about healthy physical activity( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 21 ). Behavioural determinants, originating from the Attitude–Social Influence–Self-Efficacy model( Reference De Vries, Dijkstra and Kuhlman 36 ), were confirmed and other relevant themes, including midwives’ perception of their role in health promotion, were added to our hypothetical model explaining midwives’ behaviour in respect to promoting healthy GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 21 ).

Our cross-sectional survey study of midwives included 112 practising community midwives( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ). We found that midwives considered measuring weight, discussing GWG, education about healthy diet and, to a lesser extent, education about healthy physical activity to be part of their practice( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ). Midwives also agreed that discussion about public health issues (i.e. women’s health) was very important and they regularly discussed health promotion issues (e.g. physical well-being, social support, emotional coping) with their clients. Midwives offered more GWG monitoring when they had more positive attitudes towards it, experienced more supportive social influences concerning monitoring GWG and had fewer barriers to GWG monitoring( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ). Education about diet and physical activity was more likely among midwives with more positive attitudes towards it, higher reported self-efficacy, more social influences supporting education on diet and physical activity, and greater activity in health promotion( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ).

The literature on existing interventions aiming at healthy GWG revealed that most interventions were developed in the USA and Europe; half of the interventions focused on a single theme (e.g. on diet or physical activity), while the other half combined diet, physical activity and attention to weight. A meta-analysis showed that interventions focused on diet for obese women resulted in a mean difference of −8·41 kg (95 % CI −10·49, −6·34 kg), interventions focused on physical activity resulted in a mean difference of −0·83 kg (95 % CI −1·47, −0·19 kg) and interventions with multiple content had no significant effects. Secondary outcomes (e.g. change in diet) were inconsistent. We found only one study of healthy pregnant women( Reference De Vries, Dijkstra and Kuhlman 36 ).

As a result of our needs assessment (and including the advice of the consortium) we decided that our intervention should target two groups: (i) healthy pregnant women; and (ii) community midwives.

For each target group, a behavioural objective was formulated. Our intervention was designed to:

-

1. Help healthy pregnant women to stay within the IOM guidelines; and

-

2. Get midwives to adequately support the efforts of healthy pregnant women to gain weight within the IOM guidelines.

Step II: Formulation of change objectives

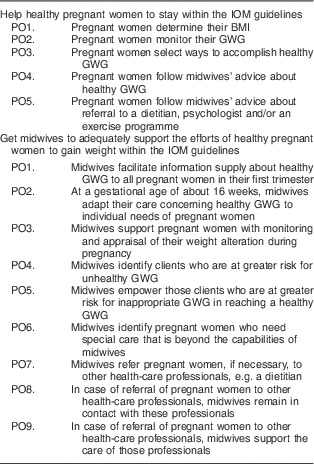

Table 1 shows the behavioural objectives translated into performance objectives providing answers to the question: ‘What do participants of the programme need to do to succeed in the recommended health-related behaviour?’

Table 1 Performance objectives for pregnant women and midwives

PO, performance objective; IOM, Institute of Medicine; GWG, gestational weight gain.

We identified important and changeable behavioural determinants based on our literature review( Reference Merkx 19 ), the surveys of pregnant women and midwives( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 21 , Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ), existing literature about determinants of (un)healthy GWG and feedback from the consortium.

The determinants of pregnant women’s behaviour included: awareness of the importance of healthy diet and sufficient physical activity in relation with their GWG and their (baby’s) health( Reference Szwajcer, Hiddink and Maas 37 ); knowledge of their own height and weight( Reference Herring, Oken and Haines 38 ), calculation of their BMI and GWG recommendations( Reference Herring, Nelson and Davey 39 ), negative consequences of too low and too high GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Olander, Atkinson and Edmunds 33 , Reference Groth and Kearney 40 ), positive consequences of healthy GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ) and the positive influence of a healthy diet and healthy physical activity on GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Herring, Oken and Haines 38 , Reference Herring, Henry and Klotz 41 , Reference Herring, Rose and Skouteris 42 ); attitudes towards a healthy GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Palmer, Jennings and Massey 43 , Reference Tovar, Chasan-Taber and Bermudez 44 ), a healthy diet and healthy physical activity, and following the advice of midwives( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Althuizen, van Poppel and Seidell 28 , Reference Stengel, Kraschnewski and Hwang 34 , Reference Paul, Graham and Olson 45 – Reference Stotland, Haas and Brawarsky 48 ); social influence of family members (such as partners and mothers; information aroused during consortium meetings) and midwives( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Olander, Atkinson and Edmunds 33 , Reference Stengel, Kraschnewski and Hwang 34 , Reference Stotland, Gilbert and Bogetz 49 ); self-efficacy expectations/skills with regard to assessing one’s BMI( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ), monitoring GWG( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Paul, Graham and Olson 45 ), healthy diet and healthy physical activity( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 , Reference Paul, Graham and Olson 45 ), discussing exceeding IOM recommendations with the midwife and resisting well-meant advice from friends and family members; and barriers like no scale at home (information aroused during consortium meetings), pregnancy-related changes in diet preferences( Reference Herring, Henry and Klotz 41 ), morning sickness and other physical complaints( Reference Cramp and Bray 50 ), and the combination of pregnancy with care for other young children( Reference Cramp and Bray 50 ).

The determinants of midwife behaviour included: awareness of their role in promoting healthy diet and physical activity( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 21 , Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ); knowledge, including consequences, of healthy GWG, diet and physical activity, of cut-off points of healthy GWG and of diet and physical activity advice( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 21 , Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 , Reference Olander, Atkinson and Edmunds 33 , Reference Cogswell, Scanlon and Fein 46 ); attitudes towards encouraging healthy GWG, healthy diet and physical activity( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ); perceived social influences from clients, clients’ partners, colleagues, the Royal Dutch Organization of Midwives, obstetricians( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ) and from established guidelines( Reference Jans, de Jonge and Henneman 51 ); self-efficacy expectations/skills towards tailoring their care to the individual needs of women during the course of pregnancy( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ); and barriers including lack of time and lack of guidelines( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 25 ).

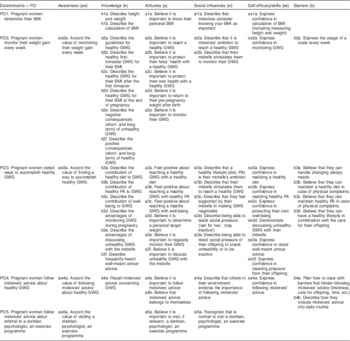

Tables 2 and 3 show the matrices of change objectives that linked objectives and determinants, based on our performance objectives and selected determinants. Each change objective specified what participants need to learn to accomplish the performance objective. For instance, Table 2 shows a cell in which the performance objective ‘pregnant women determine their BMI’ is linked with the determinant ‘knowledge’. The question used to address this cell is: ‘What knowledge do pregnant women need to determine their BMI?’ Answers to this question create the change objectives ‘Describe height and weight’ and ‘Describe the calculation of BMI’ (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2 Change objectives for pregnant women

PO, performance objective; GWG, gestational weight gain; PA, physical activity.

Table 3 Change objectives for midwives

PO, performance objective; GWG, gestational weight gain; PA, physical activity.

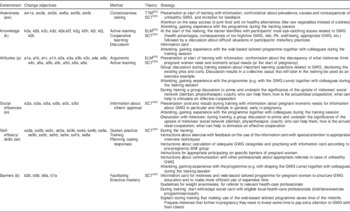

Step III: Selection of theory-based methods and practical strategies

Tables 4 and 5 show the theory-based methods and practical strategies we chose to accomplish the change objectives for pregnant women and midwives.

Table 4 Methods and strategies per determinant for pregnant women

TTM, Transtheoretical Model; SCT, Social Cognitive Theory; GST, Goal Setting Theory; GWG, gestational weight gain; PA, physical activity; FAQ, frequently asked questions.

Table 5 Methods and strategies per determinant for midwives

TTM, Transtheoretical Model; SCT, Social Cognitive Theory; ELM, Elaboration Likelihood Model; GWG, gestational weight gain; PA, physical activity.

Pregnant women

As described above, we focused on pregnant women’s awareness, knowledge, attitudes, social influences, self-efficacy expectations and barriers regarding weight gain within the IOM guidelines. Two models provided us with a theoretical foundation for motivation change: the Transtheoretical Model (TTM)( Reference Prochaska, Redding and Evers 52 ) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)( Reference Bandura 53 ). TTM conceives a change as a process involving progress through five stages, starting with pre-contemplation and then moving to contemplation, preparation, action, with final arrival at the maintenance stage. For behavioural change purposes, the first stage needs to focus on raising one’s awareness, followed by providing knowledge and arguments in the second phase. During the preparation phase one needs to acquire practical information about behavioural change recognizing the value of social approval for strengthening intention to change. A critical feature of the action phase is the provision of information about the threats to the newly acquired behaviour( Reference Prochaska, Redding and Evers 52 ). SCT identifies the essential elements for behavioural change, including person–behaviour–environment interaction, behavioural capability (knowledge and skills), observational learning, reinforcements, expectations and self-efficacy( Reference Bandura 53 ). Drawing on these theories we identified methods for change: consciousness raising (TTM), tailoring (TTM), individualization (TTM), active learning (SCT), self-re-evaluation (TTM), modelling (SCT), guided practice (SCT), verbal persuasion (SCT) and facilitation (SCT). In addition we drew on Goal Setting Theory (GST)( Reference Locke and Latham 54 ) to motivate change in self-efficacy expectations (Table 4).

We next developed practical strategies to apply these methods of change. For instance, computer tailoring was used to provide personalized information aimed at changes in awareness, attitudes, social influences and self-efficacy expectations. The tailoring programme included a self-monitoring device at different time points during pregnancy with visual feedback showing gaining below, within or above IOM guidelines. According to Bartholomew et al.( Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 ), tailoring will be effective if there is a clear link between the characteristics of the person and the messages that address those characteristics. We created short films to provide women with information aimed at changing social influences, self-efficacy expectations and the perception of barriers. In creating the videos we selected those role models that pregnant women could easily identify with. Regular face-to-face communication between the midwife and pregnant woman was intended to reinforce the client’s awareness, attitudes, social influences and self-efficacy expectations and to reduce the influence of barriers (Table 4).

Midwives

In designing the change strategies for midwives we again used the TTM( Reference Prochaska, Redding and Evers 52 ), SCT( Reference Bandura 53 ) and a third model: the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM)( Reference Petty and Caccioppo 55 ). The first two theories are explained above. Using the insights of TTM, we sought to increase midwives’ awareness of the problem of unhealthy GWG. Discussion, arguments, active learning and cooperative learning, methods derived from the SCT, were used to increase midwives’ knowledge, influence their attitudes, correct misconceptions and create a virtual client of the type that midwives were supposed to support during pregnancy. Information about others’ approval (SCT) was included to change midwives’ perceptions of the social norms of their colleagues. Finally, guided practice and planning coping responses (SCT) were used to help midwives become more familiar with the new programme and to help them to anticipate pregnant women’s objections to change.

The ELM suggests that people have two different ways of processing information: central and peripheral. Central processing occurs when a message is carefully considered and compared against other messages and beliefs. Peripheral processing occurs when a message is processed without thoughtful consideration and comparison( Reference Petty and Caccioppo 55 ). According to Bartholomew et al.( Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 ) processing is related to higher persistence of attitude change, higher resistance to counter persuasion and a stronger consistency between attitude and behaviour. For this reason, central processing should be promoted as much as possible. Following the ELM recommendations, we derived three ways to stimulate a thoughtful approach to our message: make the message personally relevant, unexpected and repeat it regularly (Table 5).

Like we did with pregnant women, the methods chosen were combined into practical strategies. First, during training sessions midwives were informed about issues related to adequate GWG, in order to raise awareness of the problem and of their role as midwives as guardians of adequate GWG. Furthermore, the training included discussions (about participants’ experiences, facts, perceived barriers all related to GWG) and active learning (working with the tailoring programme, composing an individualized and regional overview of available health professionals they might consult). To support midwives’ face-to-face communication with pregnant women, an information sheet about healthy GWG and with suggestions about proper communication was developed (Table 5).

Step IV: Development of the intervention programme

Content of intervention

Our intervention – targeting both pregnant women and community midwives – was titled ‘Come On!’, a play on words (in Dutch) that refers to both GWG and to the need to do something.

Intervention component for pregnant women

For pregnant women we developed an online GWG programme, with the aim of informing pregnant women, in an early stage of pregnancy, about healthy GWG, healthy diet and physical activity, and providing ways to accomplish a healthy GWG. The first part of the programme consisted of a web-based, tailored programme, the completion of which took about 45 min. We tailored the programme based on pre-pregnancy BMI group (underweight, normal, overweight, obese), their TTM stages of change regarding achieving a healthy GWG, healthy diet and physical activity, and their need for information. Participants received an email with a link to the website and answered online questions on weight, height, struggles with their body weight, and knowledge of benefits and harms of too low or too high GWG. Information and tailored feedback was provided in next pages on the programme based on participants’ answers. Barriers to healthy diet were discussed when women indicated that those barriers existed. Depending on the woman’s pre-pregnancy BMI and her self-expressed weight gain goal, an ideal goal was suggested during the session. In addition, the programme included thirteen informational films on healthy GWG, pregnancy-related and healthy diet (i.e. advice on listeriosis, toxoplasmosis, intake of fish, fruits and vegetables) with an actor ‘Peggy’ in the role of health professional. Depending on answers given to questions about pre-pregnancy activities, a film on physical activity was shown. Inactive women were online, in the film, advised to become active and active women were encouraged to continue their active lifestyle. Active women performing a ‘high risk’ sport (e.g. diving, football) were advised to switch to an alternative ‘low risk’ sport (e.g. swimming, biking).

The second part of the online programme consisted of a monitoring tool. Women were invited to note their weight during their first visit and furthermore after invitation by email regularly. This invitation was sent weekly during the first ten weeks, biweekly in weeks 11 to 19, every third week in weeks 22 to 28, and at a gestational age of 32, 36 and 40 weeks. If a woman did not respond to an email invitation, she was not invited again.

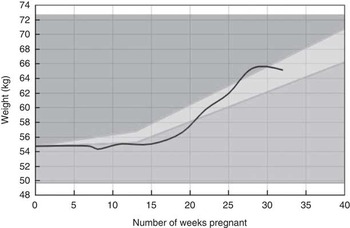

Figure 1 provides an example of an individualized graphical GWG growth curve adjusted to women’s pre-pregnancy BMI, indicating whether GWG was within, above or below the IOM guidelines. At each interval, participants received feedback plus the advice to discuss the feedback with their midwife. Each following visit to the programme ‘Come On!’, the woman was invited to watch one or more of the ten short films showing pregnant women dealing with recognizable situations. These films aimed to increase women’s awareness of healthy GWG and related behaviours (i.e. diet and physical activity), to demonstrate positive social support (e.g. from peers), to increase self-efficacy expectations (e.g. towards reaching healthy diet and healthy physical activity) and to suggest ways to overcome barriers (e.g. how to cope with cravings). Each short film lasted about 3 min. Films from the first session with ‘Peggy’ could be reviewed as well.

Fig. 1

Example of an individualized graphical gestational weight gain (GWG) growth curve (![]() ) adjusted to women’s pre-pregnancy BMI, indicating whether GWG is within (

) adjusted to women’s pre-pregnancy BMI, indicating whether GWG is within (![]() ), above (

), above (![]() ) or below (

) or below (![]() ) the Institute of Medicine guidelines for a healthy GWG

) the Institute of Medicine guidelines for a healthy GWG

The online programme was illuminated with a consistent logo and illustrations to increase attractiveness. Written language was kept at a level appropriate for women with low and moderate levels of education.

Intervention component for midwives

The intervention component for midwives included training and an information card. Because some midwives delegate certain activities (e.g. intake interview, lifestyle education) to practice assistants, these assistants were invited for the training as well. Midwives/assistants received 4 h of training at a location in or nearby their working environment. The training was led by the first author (A.M.) who is experienced in professional education. In total the training was delivered ten times; sixty midwives and twelve assistants participated. At the start of the training, participants were invited to talk about their experiences and perceived problems in relation to GWG with the aim of raising awareness of appropriate GWG and of their care provided to achieve appropriate GWG. They received oral and written information on the IOM guidelines on GWG, the consequences of (un)healthy GWG, pregnant women’s behaviours related to GWG, the determinants of those behaviours, and the behaviours of Dutch midwives concerning GWG and the determinants of those behaviours. The goal was to make midwives aware of the gap between pregnant women’s needs and the current practice of midwives. The training introduced the online GWG programme for pregnant women. Finally, midwives were advised to discuss GWG at least once during antenatal care, to discuss healthy diet and physical activity, and to refer women to a dietitian and/or a physical activity programme for pregnant women. Midwives were instructed about the use of the information card, which included summarized information, arguments for referral to a dietitian, psychologist or physical activity programme, and suggestions for questions. During the training, midwives created a list of regional health-care workers they might refer their clients to or ask for advice. They were also encouraged to take a look at their own websites, in order to identify gaps in information about healthy lifestyles.

Step V: Development of an adoption and implementation plan

Because the ‘Come On!’ intervention is a newly developed programme, we followed the recommendation of Bartholomew et al. to include step V in the overall programme planning( Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 ). Consortium midwives functioned as intermediaries between developers and the final users (pregnant women and midwives) during steps I–IV. Building on a relationship of trust with their pregnant clients, midwives collect broad understanding of their clients. The consortium midwives and dietitian provided valuable information about relevant impeding and enhancing factors concerning implementation in midwifery practices. For instance, to minimize midwives’ time spent discussing healthy GWG, pregnant women can use the online ‘Come On!’ programme with minimal interference of the midwife, except for one single referral to the website. Midwives in the consortium consulted with their colleagues in the field about the relevant (important and changeable) determinants that formed the starting point for ‘Come On!’ and about selected practical strategies that were included. An essential part of ‘Come On!’ was the training for midwives, organized to inform them about the purpose and procedures of the intervention and to practise skills that were part of the intervention, and at the same time to facilitate adoption and implementation. The pilot test (step VI) of the intervention produced information from pregnant women and midwives about their experiences and appreciation of the programme, both of which were relevant for implementation.

Step VI: Development of an evaluation plan

The effect of ‘Come On!’ was evaluated in a non-randomized pre–post intervention study among pregnant women, comparing a historic control cohort (running May–August 2013) with an intervention cohort (running April–July 2014). First, consortium midwives recruited seventeen midwives. Then, the participating midwives were entrusted with the task of including pregnant women for the control cohort and the intervention cohort. Midwives or their practice assistants informed adult pregnant women with a singleton pregnancy about the study during the first telephone contact. If women were open to information about the study, their name and email address were collected and sent to the researcher (A.M.). The researcher then emailed the woman detailed information about the aim and procedures of the study. When the woman agreed to participate, she was invited to send a confirmation email to the researcher. Following this email, the researcher sent a link to the first digital questionnaire. Before their first antenatal visit to the midwife, and at about 36 weeks of pregnancy, pregnant women completed an online questionnaire that was similar to the questionnaire used in the needs assessment. Except for items on demographics in the first questionnaire (e.g. age, education), both questionnaires consisted of items on weight, diet and physical activity. For process evaluation purposes( Reference Steckler and Linnan 26 ), pregnant women from the intervention cohort answered questions related to exposure, use and appreciation of ‘Come On!’ in the second questionnaire. Likewise, the midwives answered questions related to the quality of the training, fidelity and dose of the programme delivered, usefulness of the ‘Come On!’ programme and barriers for use. Furthermore, the online programme reported user analytics about programme use. The Research Ethics Committee of Atrium-Orbis-Zuyd reviewed the study protocol and provided ethical approval (number 14-N-41). The trial study was registered in the Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR) under number NTR4717. We are in the process of presenting the results of this evaluation study.

Discussion and conclusion

The current paper presents a detailed outline of the process we used to develop ‘Come On!’, a programme intended to promote healthy GWG among healthy pregnant women. The needs assessment (intervention mapping step I) provided the information about personal and environmental factors related to GWG that was needed to formulate programme goals and specific change objectives. The use of a consortium of advisors, starting with the first step of intervention mapping, ensured that we took into account individual and environmental factors related to GWG, and that we continuously incorporated the adoption and implementation preferences of the intended users. The goal of the ‘Come On!’ programme was to make healthy pregnant women aware of an adequate GWG and to provide them with tools to help them stay within the IOM guidelines for healthy GWG. The web-based part could be used at any time, at any place, was widely accessible in a relatively inexpensive way, and allowed for tailoring, all of which are favourable for effective health promotion efforts( Reference Bennett and Glasgow 56 , Reference Webb, Joseph and Yardley 57 ). The training for midwives fit with the current movement of lifelong learning( 58 ).

One of the challenges during the development process was to translate results of existing studies focusing on specific target groups (e.g. overweight, obese, diabetes) to our population of healthy pregnant women. We dealt with this through our quantitative study of healthy pregnant women from the practices of community midwives( Reference Merkx, Ausems and Bude 20 ) and through the continuous interaction between the developers and the consortium (midwives, dietitian), who provided insights into GWG-related behaviours, specific needs and applicability of selected strategies within our target groups. This interaction provided the empirical and theoretical foundation for the decision-making process.

Although we found intervention mapping to be useful, it was also time-consuming. Intervention mapping is typically applied to simple and unidimensional behaviours and can become unwieldy when applied to complex behaviours such as healthy GWG promotion( Reference Kwak, Kremers and Werkman 59 ). During the needs assessment the complexity of GWG became clear, and use of intervention mapping resulted in the collection of a large and complex amount of information. Prioritizing based on impact and changeability resulted in the elimination of some relevant factors in favour of others judged to be more changeable and with a higher impact. The results of the effect and process evaluation studies will provide insights into the wisdom of these judgements (A Merkx, M Ausems, L Bude, et al., unpublished results).

We used a purposive sample of midwives and thus it is plausible that these midwives had above-average interest in issues regarding GWG and were highly motivated to find solutions. This may distort a realistic view of the factors and solutions related to the problem of healthy GWG. However, according to Roger’s Diffusion of Innovation Theory, the involvement of early adopters – an apt description of the consortium midwives – is necessary for the development and implementation of new initiatives( Reference Bartholomew, Parcel and Kok 18 , Reference Rogers 60 ). Also the recruitment of participants for the effect study by the consortium midwives might have resulted in a study population that is not generalizable to the larger population of healthy pregnant women.

The ‘Come On!’ intervention was developed in a careful and comprehensive way. We look forward to the evaluation of the programme in a representative sample of pregnant women.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This study is part of the research project ‘Promoting healthy pregnancy’, funded by Regional Attention and Action for Knowledge (RAAK PRO 2-014). RAAK is managed by the Foundation Innovation Alliance (SIA, Stichting Innovatie Alliantie) with funding from the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW). RAAK, SIA and OCW had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: A.M. is the first author and conducted the study. M.A. prepared and supervised the study and contributed to the writing process. R.d.V. is responsible for the whole study, supervised the study and edited the paper. M.N. is responsible for the study, prepared and supervised the study and edited the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: The Research Ethics Committee of Atrium-Orbis-Zuyd reviewed the study protocol and provided ethical approval (number 14-N-41). The trial study was registered in the Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR) under number NTR4717.