There is ample scientific evidence that the dietary patterns of children and adolescents have a significant influence on their immediate and long-term health and well-being( Reference Von Koerber, Männle and Leitzmann 1 – Reference Law 3 ). A diet rich in fruits and vegetables (F&V) is recognized to be a cornerstone in lowering the risk of chronic diseases such as CVD or cancer( Reference Boeing, Bechthold and Bub 4 – 7 ). Despite these health benefits, consumption of F&V by children falls well below the recommended daily amounts( Reference Currie, Zanotti and Morgan 8 – 10 ). In Germany, a study by the Robert Koch-Institute( Reference Mensink, Heseker and Richter 11 ) revealed that only 7 % of 6–11-year-old girls and only 6 % of 6–11-year-old boys reach the daily recommendation for vegetables( Reference Alexy, Clausen and Kersting 12 ) and only 19 and 15 %, respectively, reach the daily recommendation for fruits( Reference Mensink, Heseker and Richter 11 ). The results are similar for other countries( Reference Yngve, Wolf and Poortyliet 9 ).

The framework of the Social Cognitive Theory, as one of the contemporary theories to understand human nutritional behaviour, is often used in the development and analysis of nutritional intervention studies( Reference Baranowski, Davis and Resnicow 13 – Reference Contento, Balch and Bronner 17 ). According to this theory, nutritional behaviour is a complex construct( Reference Glanz and Bishop 15 , Reference Bandura 16 , Reference Bandura 18 ) with multiple factors such as personal (gender, age or migration background), behavioural (involvement in food preparation) and environmental (availability of or accessibility to F&V) factors and interdependencies among these( Reference Baranowski, Davis and Resnicow 13 – Reference Bandura 16 , Reference Bandura 18 , Reference Bandura 19 ). Nutrition-oriented interventions in school settings can address environmental as well as behavioural factors and thus are considered potentially valuable for promoting children’s health( 20 ).

Indeed, studies evaluating F&V interventions in schools reveal that such schemes can be a very effective mechanism for improving F&V consumption by children( Reference Evans, Christian and Cleghorn 21 – Reference Knai, Pomerleau and Lock 24 ). Since interventions in schools allow to address the demographically widest sample of the target population, reaching children of most socio-economic backgrounds, they can play a central role in promoting a diet rich in F&V, inducing improvements also among disadvantaged socio-economic groups( Reference Heindl and Plinz-Wittorf 25 – Reference Pérez-Rodrigo, Klepp and Yngve 27 ).

Thus, to promote consumption of F&V among European school-aged children, EU Agriculture Ministers agreed in November 2008 to introduce the School Fruit Scheme (SFS)( 28 ).

In North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW; the largest federal state of Germany), the SFS was initiated in March 2010. It started in 355 schools consisting of 289 elementary and sixty-six special-needs schools. Every pupil received 100 g F&V each day, financed by the EU and the federal state. Generally, F&V were served in the participating schools as a snack during morning break. However, whether F&V were prepared by pupils, parents, teachers or kitchen staff varied from school to school.

The objective of the current paper was to analyse if the SFS in NRW was able to increase children’s F&V intake frequency after the ending of a one-year, free-of-charge intervention of daily F&V provision.

Methods

Study design and sample

To analyse whether the SFS in NRW had been successful in increasing schoolchildren’s F&V intake, a pre-test/post-test design was used with an intervention group (eight primary schools) and a control group (two primary schools). The impact of the SFS was assessed at baseline (prior to intervention) in spring 2010 and one year after the implementation of the intervention in spring 2011 (follow-up). Ten elementary schools were selected for the study: eight of the 355 schools taking part in the SFS in NRW (intervention group) and two elementary schools in NRW that did not want to participate in the scheme (control group). To secure a high heterogeneity among schools, the sample included schools with a high and low level of social deprivation and schools with a high and low degree of nutrition education. Social deprivation was classified (high/low) according to criteria set by the Ministry for Climate Protection, Environment, Agriculture, Conservation and Consumer Protection (MKULNV) of NRW, combined with assessments of the headmasters regarding the level of social deprivation of their students. Degree of nutrition education was grouped (high/low) based on the participating schools’ nutrition education concepts. The study had a quasi-experimental design as schools had to apply for the SFS and had to be selected by the MKULNV of NRW to become part of the SFS, making it impossible for the researchers to randomly assign schools to experimental and control groups.

Instruments

Surveys were conducted with children, parents, teachers and headmasters to gain comprehensive information with regard to the perception, organization and success of the SFS. The present paper focuses primarily on the findings obtained from the children’s survey.

Children had to fill in a 24 h dietary recall as a whole class exercise. Two versions of the questionnaires were developed, one for children staying at school for lunch and the other for those going home for lunch. The 24 h dietary recall used in the present study was originally developed within the scope of the ‘Grab 5 Project’ in the UK and has been adjusted to German conditions. The questionnaire’s critical aspects of validity, statistical reliability and sensitivity to change were tested in a 3-year study in the UK( Reference Edmunds and Ziebland 29 ). A pre-test of the adapted German version of the questionnaire was conducted in two elementary-school classes. Only questionnaires of children with completed baseline and follow-up 24 h dietary recalls and those revealing reasonable data (e.g. F&V consumption frequency less than 7 times/d) were considered in the analysis. The 24 h recall allowed F&V consumption frequencies to be traced to different times of day. In addition, children were asked about their age, gender and migration background (no, one parent or two parents). Moreover, in 2011, children in the intervention group were requested to evaluate the SFS on a 5-point smiley scale (‘very good’=5 to ‘very bad’=1). The parents’ social status was identified by means of a written survey addressed to parents including questions on their educational level and employment status. This information served to calculate the ‘Brandenburger Sozialindex’( Reference Böhm, Ellsäßer and Lüdecke 30 ). The study and data handling were approved by the Ministry of Education and the MKULNV of NRW as well as by the data protection officer of the University of Bonn. Anonymized number codes allowed to link baseline data to follow-up data for each individual.

Statistical analysis

The impact of the intervention was measured by changes in F&V consumption frequencies. Potatoes, F&V juices and most of the composite foods were excluded from the analysis. Based on a quantitative content analysis( Reference Rössler 31 ) the F&V intake frequency per day was counted. Two students, both with approximately 20 h of formal training, conducted the coding of the 24 h food recalls provided by the children. Intercoder reliability was assessed by Holsti’s method( Reference Holsti 32 ) with an overall agreement between coders of 0·98( Reference Rössler 31 ). Differences between the intervention and control groups at baseline concerning age, gender, migration background, parents’ social status and children’s stay at school for lunch (yes/no) were explored using the χ 2 test and Student’s t test. The Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data was applied to compare F&V consumption frequency of the intervention and control groups at baseline. To analyse the changes in F&V consumption frequency between baseline and follow-up, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for paired samples was used. Moreover, to account for the clustered data structure (time, children and classes), hierarchical linear modelling was implemented using the framework provided by Raudenbush and Bryk( Reference Raudenbush and Bryk 33 ).

First, a three-level model without structural covariates was estimated dividing the total variance in children’s F&V consumption frequency into three components, namely time, children and class. A fourth level for the component, school, would have been desirable to consider. However, this was not possible given the small number of schools (ten schools) in our sample. In order to estimate the effect of explanatory factors on children’s F&V consumption frequency, children and class characteristics were included in the unconditional model. The explanatory variables of intervention status, gender, stay at school for lunch (dummies) and age were included (fixed effects) additionally. The variable age was coded as grand mean centred to simplify model interpretation and to reduce estimation errors( Reference Rasbash, Steele and Browne 34 , Reference Healy 35 ). Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20.0, while MLwiN 2·26 (University of Bristol, Bristol, UK) was used for the multilevel modelling approach. Type 1 error rate was set at an α level of P<0·05.

Results

Sample characteristics

At baseline in 2010, 587 second and third graders completed the questionnaire; of those, 512 also took part in the follow-up survey in 2011 (as third and fourth graders). Exclusion of children who were ill the day before data collection and of children with inconsistent data resulted in 499 children for whom baseline and follow-up data were available (390 in the intervention and 109 in the control group). In the intervention group the mean age was 8·35 (sd 0·80) years, while children in the control group were slightly older (8·67 (sd 0·78) years; P=0·000). In the latter group a smaller proportion of children stayed at school for lunch compared with the intervention group (27·7 v. 36·4 %; P=0·037). No difference existed regarding gender (P=0·558), migration background (P=0·309) and parents’ social status (P=0·435) between the control and intervention groups.

Children’s evaluation of the School Fruit Scheme

Children highly appreciated the SFS. More than 90 % evaluated the programme positively (70 % gave the highest and 20 % gave the second highest score on a 5-point smiley scale from ‘very positive’ (=5) to ‘very negative’ (=1)). Seventy-eight per cent of the children responded to the request to state what they liked about the programme (open question). The taste and the opportunity to eat their favourite F&V were mentioned most often. In addition, 31 % of the children provided information on what they did not like (open question). Lack of taste of some of the F&V served in the framework of the SFS was stated most frequently.

Effect of the School Fruit Scheme on fruit and vegetable consumption frequency

The intervention and control groups were comparable regarding the frequency of their F&V consumption per day at baseline (see Table 1). As expected, F&V consumption in the baseline study was low. The 24 h recall revealed that 36·9 % of the children in the intervention group and 32·1 % of the children in the control group did not eat any F&V the day before data collection. Of those who indicated that they had eaten F&V the previous day, the consumption frequency ‘once a day’ was most often mentioned (29·0 % in the intervention group and 32·1 % in the control group).

Table 1 Consumption frequency of fruits and vegetables (F&V; times/d) in 2010 and 2011, as well as respective changes( Reference Methner 47 ), in the intervention and control groups of primary-school children aged 6–11 years, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

* Mann–Whitney U test for two independent samples.

† Wilcoxon test for two dependent samples: 2010 v. 2011.

Compared with baseline, average F&V consumption frequency per day increased significantly in the intervention group in 2011, whereas there was a non-significant decline in F&V consumption frequency per day in the control group (see Table 1). In line with this development, a significant difference existed in total frequency of F&V consumption in the follow-up study between the intervention and the control groups (see Table 1). In the intervention group both genders increased their F&V consumption frequency (P=0·000). Nevertheless, girls ate F&V more often than boys did. This was true for both the baseline (1·50 (sd 1·46) v. 1·01 (sd 1·22) times/d) and the follow-up study (2·32 (sd 1·31) v. 1·70 (sd 1·28) times/d, respectively; both P=0·000).

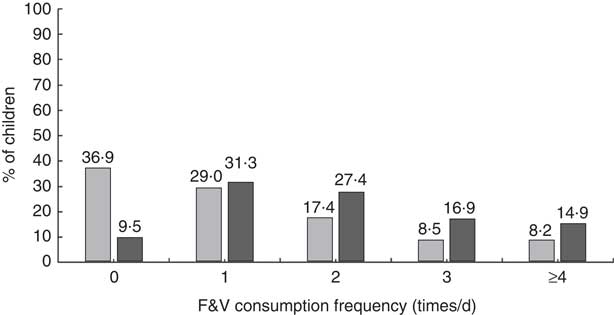

Figure 1 provides information on the proportion of children with F&V consumption frequency of 0, 1, 2, 3 or ≥4 times/d at baseline and follow-up for the intervention group. It demonstrates that the proportion of children with no F&V consumption in the intervention group declined considerably from 36·9 to 9·5 %, whereas the proportions of children with consumption frequencies of 1 time/d or above increased considerably. The situation proved quite different for the control group. In this group the proportion of children not consuming F&V even increased slightly (from 32·1 to 37·6 %; data not shown).

Fig. 1 Proportions reporting different consumption frequencies of fruits and vegetables (F&V) per day in 2010 (![]() ) and 2011 (

) and 2011 (![]() ) in the intervention group (n 390) of primary-school children aged 6–11 years, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

) in the intervention group (n 390) of primary-school children aged 6–11 years, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Providing children with F&V at school might lead to a reduction in consumption during the rest of the day. Thus it is interesting to consider the change in consumption by time of the day at baseline and follow-up for the intervention and control groups. The results showed that the intervention group had significantly increased their F&V consumption frequency before midday from 0·17 times/d at baseline in 2010 to 0·97 times/d (P=0·000) at follow-up in 2011. This increase was not compensated by a significant reduction in consumption over the rest of the day (data not shown). Moreover, in 2011, the intervention group ate F&V before midday significantly more often than the control group (0·97 v. 0·23 times/d; P=0·000). In the control group, no significant differences in F&V consumption frequency could be detected for any time of the day between baseline and follow-up (data not shown).

The results of the hierarchical linear modelling are summarized in Table 2. Table 2 indicates that in the unconditional three-level model (Model 0), 6·3 % of the variance in children’s F&V consumption frequency per day can be attributed to the class level, 16·9 % to the child level and 77·3 % to the time level (two measurements: 2010 and 2011). The inclusion of the intervention variable had a highly significant impact on children’s F&V consumption frequency per day (β=0·763; 95 % CI 0·58, 0·95) and led to an improvement of the model as measured by a comparison of the likelihood ratio test of Model 1 and Model 0. Even after controlling for gender, age and stay at school for lunch, the intervention variable remained highly significant (β=0·773; 95 % CI 0·59, 0·96). Due to a large number of missing values for the variables parents’ social status and migration background, and only little influence on the results from leaving out these variables, we conducted model estimation without these variables. Gender proved to be the only significant control variable. The results indicated that girls ate F&V more often than boys did.

Table 2 Hierarchical linear model to estimate the intervention effect( Reference Methner 47 ) of the European School Fruit Scheme in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, on the fruit and vegetable consumption of primary-school children aged 6–11 years

* n time 998.

† n children 499.

‡ n classes 34.

Discussion

Our results provide evidence that the SFS as implemented in NRW in 2010 led to a significant increase in children’s F&V consumption after one year of participation.

To our knowledge, documentation of the impact of the SFS in Germany is still limited to evaluation reports prepared for the respective funding organizations. As they do not include any econometric modelling, they are not able to identify the main factors influencing the impact of the SFS on children’s F&V consumption. Thus the present study is the first one for Germany to obtain statistical insights from application of econometric methods.

On average, children in the intervention group showed an increase in F&V consumption frequency of 0·76 times/d between baseline and follow-up, while there was a slight, although insignificant, decline in F&V consumption frequency in the control group. The literature review by Knai et al. covering a broad scope of interventions aimed at promoting F&V consumption of children in different countries described positive changes in F&V consumption of between 0·30 and 0·99 servings/d( Reference Knai, Pomerleau and Lock 24 ). Although we measured consumption in frequencies per day and not in servings per day, our results can be considered comparable to the ones summarized in Knai et al.( Reference Knai, Pomerleau and Lock 24 ). The same holds true if compared with the results of the review articles of school-based interventions by de Sa and Lock( Reference De Sa and Lock 23 ), French and Stables( Reference French and Stables 36 ) as well as Evans et al.( Reference Evans, Christian and Cleghorn 21 ).

The present study was based on almost the same 24 h dietary recall questionnaire developed and validated by Edmunds and Ziebland( Reference Edmunds and Ziebland 29 ) and used in the ‘Grab 5 Project’ evaluation by Edmunds and Jones( Reference Edmunds and Jones 37 ). The ‘Grab 5 Project’ aimed at encouraging children to eat more F&V by information, education and activities such as fruit tuck shops. The authors detected a slightly lower consumption increase per child of 0·5 times/d compared with the present study( Reference Edmunds and Jones 37 ). The study by Bere et al. is similar to the present one in that the authors analysed the effects of providing children with free fruit or vegetables every school day. Their results are in the same range as in the present study: children increased their F&V consumption to 0·9 servings/d( Reference Bere, Veierød and Klepp 38 ). Only few studies so far have investigated the longer-term effect of school-based intervention schemes, indicating only moderate or no lasting effects( Reference Fogarty, Antoniak and Venn 39 , Reference Bere, te Velde and Småstuen 40 ).

Analysis of gender differences in F&V intake indicated that girls eat F&V more often than boys. These results are similar to those described in other studies( Reference Currie, Zanotti and Morgan 8 , Reference Yngve, Wolf and Poortyliet 9 , Reference Fogarty, Antoniak and Venn 39 , Reference Bere, te Velde and Småstuen 40 ) and can be explained by girls’ greater liking for F&V( Reference Bere, Brug and Klepp 41 – Reference Cooke and Wardle 43 ) and boys’ lower appreciation of F&V availability( Reference Bere, Veierød and Klepp 38 ) and in general lower motivation to consume F&V( Reference Emanuel, McCully and Gallagher 44 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 45 ). In 2011, after one year of SFS, an intervention effect could be detected in both genders. However, in 2011 girls still ate F&V more often than boys.

Overall, the present analysis showed that the SFS in NRW led to an increase in F&V consumption frequency among primary-school pupils. By assessing food consumption patterns for particular times of day in our data, it became evident that children in the intervention group ate F&V more frequently before midday at follow-up than did children in the control group at follow-up, or than did the intervention children at baseline; thus suggesting an effect of the F&V provision. Moreover, there was no significant decline in the F&V consumption frequency at other times of day. Thus, we saw no substitution effect.

The study has several limitations. Due to the small sample size and the non-randomization, generalizability is confined. The consideration of primary-school children’s cognitive ability limits the choice of suitable instruments to measure consumption. We used a 24 h recall, thus measuring consumption on the previous day that could have deviated from the usual consumption pattern of the respective child. However, the questionnaire used was specifically developed for this age group( Reference Edmunds and Ziebland 29 ) and has the advantage of being sensitive to even small changes in consumption patterns( Reference Edmunds and Ziebland 29 , Reference Eriksen, Haraldsdóttir and Pederson 46 ). An analysis of children’s food consumption over more than one day based on several 24 h recalls would have been desirable, but was beyond the scope of the present study. Another limitation is that there was no possibility to test for a long-term intervention effect (post-intervention run-out).

Conclusions

The current study provides evidence for the effectiveness of the SFS in NRW. Our results show that the scheme has been successful in increasing children’s consumption frequency of F&V per day, after one year of intervention. The results also show that the regular provision of F&V is highly appreciated by the children. Future studies should include larger samples, measure children’s consumption over more than one day, and investigate the longer-term effects of the SFS on children’s F&V consumption.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the schools in NRW that served as study sites for the current analysis. Financial support: This work was funded by the MKULNV of NRW. The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: All authors state that there are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: G.M. and M.H. designed the study, G.M. and especially S.M. conducted the data collection and developed the coding form. S.M. supervised and controlled the coding and conducted the statistical analyses, the latter with input from G.M. and M.H. S.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript that was revised by M.H. All authors made substantive intellectual contributions to the scientific content and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The study and data handling were approved by the Ministry of Education and the MKULNV of NRW as well as by the data protection officer of the University of Bonn. Anonymized number codes allowed to link baseline data to follow-up data for each individual.