It is estimated that the global prevalence of transgender and gender nonconforming people is 4·6 per 100 000 individuals, or 1 in every 21 739 individuals, with a significant increase in the last 50 years(Reference Arcelus, Bouman and Van Den Noortgate1). Some transgender people seek to express their gender identity(Reference Connell and Pearse2) by realising a gender transition (Fig. 1), a process that can involve everything from changing clothes, names and pronouns to health needs, such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and/or gender affirming surgeries (GAS), which include surgical interventions such as vaginoplasty, mastectomy, phalloplasty and hysterectomy among others(3). Such interventions are sought by about 80% of the transgender population and are directly related to well-being(Reference Radix, Eckstrand and Ehrenfeld4).

Fig. 1 Gender classification in cisgender and transgender, accordingly continuity or discontinuity concerning sex and gender identity. We use the term cisgender to describe a person to whom the gender identity matches with the sex assigned at birth, and transgender to a person to whom that correspondence does not exist. The sex assigned at birth corresponds to biological features, that is, sexual organs, reproductive structures and hormones. However, bodies encompass broader social and cultural meanings, such as techniques, rules about how to be ‘man’ or ‘woman’, behaviours, costumes and preferences. We name gender identity the way people perceive their selves in this socio-cultural system. This concept is not limited to masculine or feminine characteristics but to several possibilities that mix different characteristic of genders or none of them(Reference Connell and Pearse2,3)

Transgender people suffer many forms of stigma throughout their lives. The Gender Minority Stress Theory proposes that the stigma attached to gender identity adversely affects health: in the short term, with the body’s response to stress and elevation of cortisol levels, but also chronically by contributing to the development of non-transmissible chronic diseases, communicable diseases and mental health problems(Reference Hendricks and Testa5). Stigma against transgender people is expressed in various ways, including social exclusion by family and friends; physical and mental violence from both relatives and strangers; and through the institutional creation of barriers to access in education, health, work and social services, thus affecting all aspects of social life(Reference White Hughto, Reisner and Pachankis6).

Most gender studies in the fields of food and nutrition emphasise sexual and reproductive differences, accounting for only the binary conception of man and woman. Yet gender relations are involved in the development of obesity(Reference Kanter and Caballero7), in determining food insecurity(Reference Lessa and Rocha8) and in eating behaviours(Reference Spencer, Rehman and Kirk9), among others. Consolidated surveys provide a basis for anthropometric and food consumption parameters and present specific recommendations based on gender. However, though important for orienting populations around the world, such recommendations do not address individuals who are transgender(Reference Linsenmeyer, Drallmeier and Thomure10). To promote gender-based nutritional and food care, we need to know what nutritional and food research informs us about transgender communities.

In this paper, our general premise is that the experience of transgender individuals affects their food and nutritional demands differently than cisgender people, and therefore, needs to be included in recommendations, guidelines, and food and nutrition policies. We highlight the two principal issues that are responsible for mobilising our hypothesis: stigma and gender transition. The stigma experienced by the transgender community impacts body and body image relationships, being associated with food intake capacity, higher cardio-metabolic risk, diabetes and mental health problems such as anxiety, depression and suicide(Reference White Hughto, Reisner and Pachankis6). HRT is thus a healthcare need that is also used as a strategy to alleviate social suffering. HRT confers changes in body composition, principally through redistribution of fat and muscle mass, which may be similar or not to the intended gender, since the desired gender is not necessarily the opposite of the sex attributed to birth(Reference Radix, Eckstrand and Ehrenfeld4). To discover the repercussions of these dimensions and others on transgender food and nutritional demands, we see the need to gather more evidence.

Our aim with this review is to gather and organise transgender population studies in the fields of food and nutrition. We set this goal by considering that research on food and nutrition for transgender people is fragmented and needs to be connected to provide the state of evidence we have available up to date about this topic. We sought to systematise and characterise the knowledge thus far produced so that future research may be performed to fill the identified gaps. We guided our review based on the following question: What are the geographic coverage, themes, and methodological and principal approaches in food and nutrition research that address the transgender population? As geographic coverage, we considered the period in which the surveys were performed and the countries of origin of both the researchers and participants. As themes, we considered the general areas in which the study might be linked to the objective. As methodological approaches, we considered study designs and techniques; finally, we identified the main results, conclusions and contributions related to the transgender population and food and nutrition.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations. We did not register our protocol for this review because our research does not directly analyse health-related results.

Search strategy

We conducted the search between the months of June and July of 2020. The search strategies were developed based on consultations with specialists in the field, as well as a previous comprehensive food and nutrition studies review(Reference Ottrey, Jong and Porter11). To cover as many terms as possible related to the transgender population, we used the most frequent words, extracted from a systematic review of LGBTQ theme reviews(Reference Lee, Ylioja and Lackey12).

The terms: (FOOD OR DIET OR NUTRITION OR EATING) and (TRANSSEXUAL OR TRANSSEXUAL OR TRANSGENDER OR TRANSVESTITE OR TRANS-SEXUALITY OR ‘GENDER DYSPHORIA’). We conducted searches in the Scopus, MedLine/PubMed (via the National Library of Medicine) and Web of Science databases, all of which revealed excellent performance in gathering evidence for systematic reviews(Reference Bramer, Rethlefsen and Kleijnen13) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S1).

Study selection

The titles and abstracts were read by two independent authors (S.M.G. and M.F.A.M.), and in case of disagreement, a third author was consulted (M.C.M.J.). We relied on the assistance of Mendeley and Rayyan Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) reference managers to combine the databases, exclude duplicates, read titles and abstracts, and select and analyse disagreements.

Studies conducted in the field of human and dietary nutrition were included, without limitation as to year, language or study design. Studies with a specific focus on hormonal treatment, literature reviews, theoretical essays, abstracts, dissertations, theses, books or articles whose titles that were not available for reading in the referenced journal were excluded.

The complete texts were retrieved and revised by S.M.G. to confirm the study’s eligibility, and in case of doubts the other authors were consulted. A supplementary manual search was performed to identify additional studies using the references found in the selected articles.

Quality assessment

We used the following recommendations for assessing methodological quality: qualitative studies were evaluated using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ)(Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig14); cross-sectional observational studies were evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute Prevalence Studies Checklist(15). Cohort and case–control studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale(Reference Lo, Mertz and Loeb16). The observational studies were also evaluated using the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statement(Reference von Elm, Altman and Egger17). Case reports were evaluated using the Methodological Quality and Synthesis of Case Series and Case Reports(Reference Murad, Sultan and Haffar18).

Studies were classified as high quality, moderate quality or low quality, using the Jacob, Araújo and Albuquerque criteria(Reference Jacob, Araújo de Medeiros and Albuquerque19). Studies were classified as high quality when fulfilling > 80% of the criteria on the referred checklist, as moderate quality when fulfilling from 79 to 50% of the criteria and as low quality when fulfilling < 50% of the required criteria. In cases where two instruments were used and the classifications were divergent, the lower classification was considered.

Data extraction

The data were extracted by S.M.G. and verified by M.F.A.M. and M.C.M.J. We extracted the following information from the studies: author(s), country of correspondence, author, year, setting, study design, study aim, participants, data collection techniques and significant results. We obtained the Human Development Index of the corresponding authors’ countries in the 2019 Human Development Index – Ranking(20).

Summary of results

We have presented the results in a descriptive manner and using absolute frequency. We have produced summaries of each of the articles and systematised the principal conclusions. The articles were subsequently grouped according to their principal themes.

Results

Studies selection

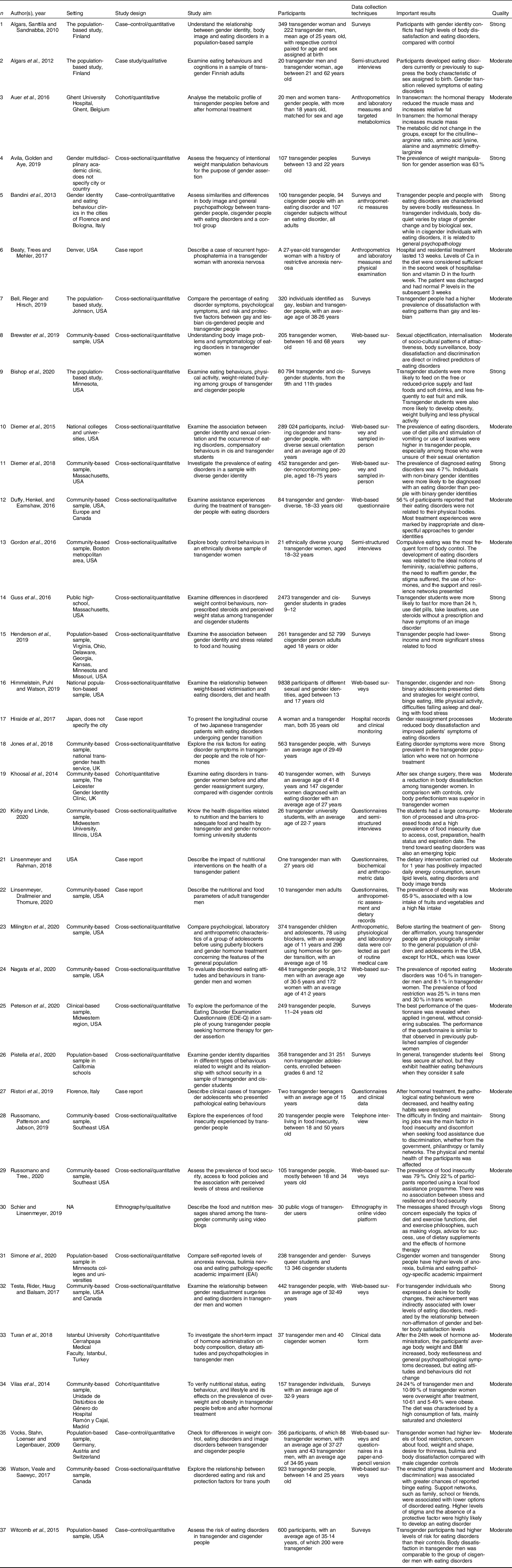

The process of identifying and selecting articles is described in Fig. 2. We identified 778 studies in the databases, 221 in MedLine/PubMed, 261 in Scopus and 296 in Web of Science. After excluding duplicate studies, 462 were maintained. We performed a thorough reading of the titles and abstracts and excluded theoretical studies, abstracts, non-peer-reviewed and out of scope articles. Of the total studies, fifty-one studies were read in full and assessed for quality; of these, thirty-seven articles were satisfactory and thus included. The selected articles are characterised in Table 1.

Fig. 2 Flow diagram of studies included in the present review on transgender peoples and food and nutrition research

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies about transgender and gender nonconforming peoples’ consideration in food and nutrition research

Study themes and characteristics

The inclusion of gender identity in food and nutrition studies is recent. The first study included in the review was published in 2009(Reference Vocks, Stahn and Loenser21) and the vast majority of such studies were published since 2015(Reference Linsenmeyer, Drallmeier and Thomure10,Reference Auer, Cecil and Roepke22–Reference Duffy, Henkel and Earnshaw51) . Of the thirty-seven studies, five concerned food and nutritional security(Reference Henderson, Jabson and Russomanno25,Reference Kirby and Linde29,Reference Russomanno and Jabson Tree37,Reference Russomanno, Patterson and Jabson38,Reference Bishop, Overcash and McGuire48) , twenty-five concerned body image and weight control(Reference Vocks, Stahn and Loenser21,Reference Gordon, Austin and Krieger23,Reference Guss, Williams and Reisner24,Reference Himmelstein, Puhl and Watson26–Reference Jones, Haycraft and Bouman28,Reference Nagata, Murray and Compte32–Reference Peterson, Toland and Matthews34,Reference Ristori, Fisher and Castellini36,Reference Simone, Askew and Lust40–Reference Brewster, Velez and Breslow47,Reference Diemer, Grant and Munn-Chernoff49,Reference Diemer, White Hughto and Gordon50,Reference Ålgars, Alanko and Santtila52–Reference Algars, Santtila and Sandnabba55) , five concerned nutritional status(Reference Linsenmeyer, Drallmeier and Thomure10,Reference Auer, Cecil and Roepke22,Reference Linsenmeyer and Rahman30,Reference Millington, Schulmeister and Finlayson31,Reference Vilas, Rubalcava and Becerra56) , one concerned nutritional health care(Reference Duffy, Henkel and Earnshaw51) and one involved emic views of healthy eating(Reference Schier and Linsenmeyer39). The most frequent study designs were cross-sectional (n 22), followed by case reports (n 5), case–controls (n 4), cohort studies (n 4) and one ethnographic study (n 1) (see Table 1).

Quality analysis

Of the articles, thirty-seven were judged to be of good or moderate quality and fourteen were classified as low quality, and thus excluded. The lower-quality studies were mostly case reports lacking accurate information concerning either diagnosis, measurement of variables or results. Though some of the selected articles presented a limited sample number, or did not clearly present the sample or selection criteria, we did not consider the limitations discovered as detracting from the merit of our review, since we had excluded those whose failings might compromise their conclusions.

Geographic coverage

The production of knowledge concerning food and nutrition for transgender people is concentrated in the Global North. Most of the principal authors of the studies were linked to institutions in North America and Europe, and in countries with a high Human Development Index (above 0·800), as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 The landscape of food and nutrition research about transgender people. Map of continents indicated where the main authors of the articles are from, and the Human Development Index of their respective countries

Principal contributions to the fields of food and nutrition

We have summarised the principal conclusions of the articles according to their themes in Fig. 4. Despite the limited number of studies in this review, the prevalence of food insecurity draws one’s attention. In general, transgender people, both adolescents and adults, suffer difficulties in access to food(Reference Henderson, Jabson and Russomanno25,Reference Russomanno and Jabson Tree37) and access to food assistance(Reference Russomanno and Jabson Tree37) and often consume ultra-processed foods(Reference Bishop, Overcash and McGuire48). All the food security studies took place in the USA, and factors associated with food insecurity involve the country’s social context, in which food assistance is largely provided by private groups within society, especially religious groups. In these cases, the principal condition that promotes removal of transgender people from food assistance programmes is stigma(Reference Russomanno and Jabson Tree37). Due to their low cost, consumption of ultra-processed foods is an alternative for high-school adolescents(Reference Bishop, Overcash and McGuire48).

Fig. 4 Broad topics of current food and nutrition research about transgender people with a summary of the main conclusions in the articles reviewed

Food is often used as a strategy for seeking comfort, and this can give rise to problematic relationships to food consumption. A link between body dissatisfaction and eating disorder diagnoses, such as anorexia and bulimia, has been demonstrated by several authors(Reference Himmelstein, Puhl and Watson26,Reference Brewster, Velez and Breslow47,Reference Diemer, Grant and Munn-Chernoff49,Reference Diemer, White Hughto and Gordon50,Reference Ålgars, Alanko and Santtila52,Reference Algars, Santtila and Sandnabba55) . Food restriction, even when not diagnosed, is most frequently used as an instrument to fit into body and gender standards(Reference Vocks, Stahn and Loenser21,Reference Nagata, Murray and Compte32) . In general, it is difficult to access treatment for eating disorder services that do not discriminate against transgender people(Reference Duffy, Henkel and Earnshaw51), leading many in the community to the internet for tips and information on diets, exercises and dietary supplements(Reference Schier and Linsenmeyer39).

For being effective in alleviating social suffering, the process of gender transition through multi-professional assistance is much needed by many transgender people. The effects of gender transition have been demonstrated not only to reduce eating disorders(Reference Testa, Rider and Haug41) but also to increase the prevalence of overweight and obesity, as well as the increased consumption of energetic foods(Reference Vilas, Rubalcava and Becerra56), which makes nutritional therapy necessary. Yet, there are no nutritional recommendations that are appropriate to the context of the transgender population(Reference Linsenmeyer and Rahman30). This is true even though certain alternatives are indeed presented during nutritional therapy, such as male and female-based reference values for the related stage of the individual’s hormonal transition (i.e., hormonal composition), and the references for the desired gender(Reference Linsenmeyer, Drallmeier and Thomure10).

Discussion

Food and nutrition issues are affected by gender in the transgender and gender nonconforming gender communities. Gender studies in the fields of food and nutrition are still recent and leave us with more questions than answers, revealing the need for further studies. In general, food is a means of minimising social suffering in transgender communities. However, in certain contexts, the stigma experienced can deepen food scarcity situations, by contributing to the already high prevalence of food insecurity, diets based on ultra-processed foods and difficulties in accessing adequate nutritional assistance networks.

Below we highlight the principal lessons learned from the systematisation in this review, as well as the need for further exploration of the experiences of food and gender in the Global South, since conclusions for the Global North alone present limited generalisation. Finally, we seek to point out ways to advance nutritional care for the transgender population in the future.

Trends in studies on gender, food and nutrition

Studies on food and nutrition for transgender people, although few, should serve as a guide for future research on the subject. We highlight three principal trends we identified: (1) the binary division of genders between male and female in dietary and nutritional recommendations is insufficient for transgender care; (2) many studies have limited conceptions about the transgender communities and (3) the stage of a gender transition can interfere with food and nutritional outcomes.

First, the contemporary public health demands challenge classic nutritional assessment methods and dietary recommendations to include the transgender population. Studies concerning recommendations for anthropometric measures and Dietary Reference Intake consider a binary division of the sexes (male and female)(Reference Linsenmeyer, Drallmeier and Thomure10). However, the studies we gathered demonstrate the effects of HRT and GAS on lipid profile, body composition, eating disorder development and behaviour in the transgender population and the need to consider such processes in their health assessments. Therefore, the global prevalence of people who do not conform to the sex attributed at birth increases and suggests the need to update protocols and current recommendations.

Second, the studies we reviewed use different criteria when considering transgender people. The majority of the research focuses on the medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria and the psychopathological relations with food. Researchers must consider the relationship between transgender communities and food cultures beyond a pathological relationship, considering specific ethical assumptions, such as acting in collaboration with the community, using stigma-free language, emphasising participant data protection and avoiding hypotheses that consider conversion, reorientation or restorative therapy(Reference Adams, Pearce and Veale57). Gender dysphoria is not the best criterion for classifying transgender people; Putckett et al. (Reference Puckett, Brown and Dunn58) suggest a two-step method for confirming gender in broad population surveys, considering the transgender population as that in which sex and gender do not match.

Finally, we also observed that the existing heterogeneity in the identities and needs of the transgender population makes it necessary to consider characteristics of the population in the development of each research question. As an example, studies related to HRT must consider that not all transgender people want or even have access to this therapy, and if they did, it might still be performed in different ways(Reference Radix, Eckstrand and Ehrenfeld4). Also, different stages of the therapy yield different results depending on the patient’s body composition, eating disorders and food consumption. In addition, having access to services that perform HRT and/or GAS is correlated with communities in terms of their access to food. Controlling such information might well be essential to better explain biological and social influences on health and nutrition in the transgender community.

Research gaps and directions for future research on gender and food

With this review, we highlight seven principal gaps we need to address to advance on food and nutrition research about transgender communities. We showed that evidence on food and nutrition in transgender persons is derived mainly from quantitative and transversal studies, without consensus about categories of analysis. Based on these findings, we propose (1) to perform more exploratory studies that enable us to formulate adequate indicators for future hypothesis tests. The evidence available so far is related to transgender people living in the context of developed countries. For this reason, we propose to the scientific community to (2) develop research in the context of the Global South, (3) analyse the influences of the diverse welfare state systems in the protection of food rights and (4) understand the historical and cultural impact of gender on the dietary habits of transgender peoples. Finally, the scientific production about this topic is concentred most in eating behaviour studies, being scarce about food security. We thus suggest (5) to explore the association between perception of food security and food consumption; (6) to indicate determinants of food insecurity in transgender communities and (7) to diversify the research approach on eating behaviour. In the next paragraphs, we explain our arguments.

We need to perform more exploratory studies (primarily ethnographic) better to understand the food and nutrition needs of transgender people. For any population, what we know is part of our generalised premises. Considering the specificities of transgender groups that we highlighted in this paper, revisiting our assumptions during our diagnosis and interventions is crucial. Exploratory studies will be useful in this task, enabling us to select proper health and well-being indicators, formulate cultural-based guidelines and understand differing outcomes of food and nutrition interventions within the transgender community.

Research on food and nutrition in the transgender community is concentrated in developed countries, with high Human Development Index, and located in the Global North. These countries lead the production of scientific knowledge worldwide and dominate the publishing market by concentrating the largest publishers, the most prominent scientific journals and the largest scientific associations. Furthermore, the older and more consolidated universities and research centres are located in the Global North and are targets for funding by the private sector(Reference Collyer59). In this context, we see limited interest in research of problems faced mostly by societies in the Global South(Reference Reidpath and Allotey60,61) .

Changes in dietary standards do not happen linearly or homogeneously between the Global North and South countries. Therefore, the generalisations of studies - markedly North American and European - remain limited. Globally, we see the tendency to increasing the consumption of ultra-processed foods and decreasing food preparation in the home environment. However, this transition occurs at different moments between countries and regions. Developed countries in the context of industrialised food systems led this transition, being accompanied in the last years by those with weakened food regulation and fragile democracies(Reference Baker, Machado and Santos62). Like Brazil, some countries in the Global South that have maintained mostly traditional eating habits for many generations in the last decade have been facing pervasive changes in their food patterns due to the lack of regulation from the state(Reference Monteiro and Cannon63). Consequently, in these countries, the impacts of dietary changes on health (e.g., non-communicable diseases) began to emerge even before overcoming fundamental problems such as malnutrition and infectious diseases, leading to an accumulation of health conditions related to food and nutrition(Reference Vorster, Bourne, Temple and Steyn64).

Specific food and health needs for transgender people may also vary according to the social and health protection systems of the country or region in which they live. In Canada, the State finances some health procedures specific to transgender people, while in Japan, HRT is not covered by the health system, and the access to GAS is limited to a few hospitals. In the USA, coverage varies, requiring co-payment by the insurance status and employer participation. In countries that require direct payment or co-payment, transition costs can reach $23 000 (USD). In South Africa, only two public clinics specialise in health care for transgender people, offering HRT and few GAS services(Reference Koch, McLachlan and Victor65). In contrast, in Brazil, the entire gender transition process is provided by the Unified Health System (SUS, in Portuguese) financed by the State(Reference Popadiuk, Oliveira and Signorelli66). Direct health costs in the general population are associated with the purchasing power of the individual(Reference Abad-Segura, González-Zamar and Gómez-Galán67) and increased food insecurity(Reference Berkowitz, Basu and Meigs68), affecting the food choices(Reference Boek, Bianco-Simeral and Chan69,Reference Glanz, Basil and Maibach70) ; in addition, access to HRT and GAS continues to influence nutritional status, body composition and eating behaviour in transgender people(Reference Auer, Cecil and Roepke22,Reference Hiraide, Harashima and Yoneda27,Reference Turan, Aksoy Poyraz and Usta Sağlam42) .

Cultural and historical aspects are also implicated in gender relations and can influence food and nutritional issues. Histories of colonialism and dictatorships present repercussions in violence levels and in the construction of masculinity and femininity standards(Reference Banerjee, Connell, Risman, Froyum and Scarborough71). A democratic environment directly impacts the security and recognition of citizenship for transgender people. Currently, 27% of the countries worldwide, concentrated in the Global South, criminalise same-sex relationships and six member states of the United Nations impose the death penalty(72). A global survey carried out by Transgender Europe shows that between the years 2008 and 2018, there were 2982 murders of trans and gender-diverse people. It is noteworthy that 88% of these murders occurred in the Global South, where many countries have colonialist inheritances(Reference Berredo, Arcon and Regalado73).

One study also included in our review revealed a potential association between the feel of security and the consumption of ultra-processed foods(Reference Pistella, Ioverno and Rodgers35). Gordon et al. (Reference Gordon, Austin and Krieger23) demonstrated a relationship between gender standards and the development of eating disorders. With the current study, we see that there is a direct relationship between stigma and violence perpetrated against transgender people and their food and nutritional needs.

In the fields of food and nutrition, despite widespread discussion of gender and food and nutrition insecurity, transgender people are only rarely considered. One study in the USA reveals the severity of the prevalence of food and nutrition insecurity in this population, reaching around 79%(Reference Russomanno and Jabson Tree37). It is necessary to explore what factors are associated with this high prevalence, and how the variables are related, whether directly or indirectly. The literature records the effects of stigma on transgender people in several dimensions involving food and nutrition insecurity, but without directly measuring them: in education, health, work and in access to income(Reference White Hughto, Reisner and Pachankis6,Reference Hatzenbuehler and Pachankis74) . And we do not know how these indicators behave in determining food insecurity in this population.

There is still a gap in nutritional approaches for care of the transgender population with eating disorders, currently limited to focuses on psychopathological issues. Research on mental health is a trend of the studies on transgender communities due to the stigma effects on quality of life and general health. However, we need to understand better the complex nexus between life experiences and socio-cultural factors in the context of transgender people(Reference Reisner, Poteat and Keatley75).

We still do not know how nutritionists and food and nutrition teams provide health services care to the transgender population. We also do not know the meanings attributed to food throughout the lives of transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. These seemingly important questions were the principal gaps discovered. We know that food is involved in a network of symbolic elements and is not limited to nutrients or their effects on health alone. For a stigma-free approach, it is necessary to train nutrition professionals to be able to explore these elements in differing gender communities.

Conclusion

We identified various research gaps, especially regarding relationships between the transgender community and food, in which illness was generally the focus of connections between them. Studies on food and nutrition for transgender people need to consider dietary practices and gender diversity in countries in the Global South since studies performed in the Global North alone possess only limited generalisation. To formulate categories of analysis which reach beyond the binary male/female gender system, exploratory studies are much needed. Despite the observed gaps, our review demonstrates that the life process of transgender people directly and/or indirectly affects relationships between the body, food and nutrition, challenging recommendations based on the binary gender system alone. This deserves to be further explored.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Fillipe Pereira for his methodological support. Financial support: This work was supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), for the PhD scholarship (grant numbers 88887.505839/2020-00). Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Ethics: No ethical approval was required for this study Authorship: S.M.G. and M.C.M.J. participated in all phases of the study. M.F.A.M. participated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work. C.R. participated in the conception of the work, drafting and revising it critically for important intellectual content. L.R.A.N. and C.O. L. contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001671