Breast-feeding has been associated with several short- and long-term health benefits for infants, including a reduced risk of developing childhood overweight and obesity(1–Reference Horta, de Mola and Victora4). This protective effect on overweight and obesity has been explained by both differences in the nutrient composition of breast milk and infant formula, as well as behavioural differences between bottle feeding and breast-feeding(Reference Bartok and Ventura5). During breast-feeding, infants need to actively suckle to draw milk out of the breast, whereas bottle-fed infants are more passive as caregivers have more control over the feeding situation(Reference Li, Fein and Grummer-Strawn6). In addition, caregivers have been reported to be more responsive to their children’s cues during breast-feeding than during bottle feeding(Reference Whitfield and Ventura7). Bottle feeding, irrespective of the type of milk, can undermine infants’ ability to regulate milk intake to match their energy intake and may lead to overfeeding and rapid weight gain(Reference Bartok and Ventura5,Reference Li, Fein and Grummer-Strawn6,Reference Li, Magadia and Fein8,Reference Ventura and Mennella9) .

Bottle feeding plays an important role in infant nutrition as caregivers frequently need to rely on this practice to conciliate their personal life with children’s feeding(Reference Lee10). Worldwide, 59 % of infants fed either breast milk or formula using feeding bottles(11). Caregivers’ decision to bottle feed their children is expected to be influenced by the sales and marketing of feeding bottles and teats(Reference Rollins, Bhandari and Hajeebhoy12). In this sense, previous research has shown that the marketing of infant formula influences caregivers’ perception of breast-feeding and can have a detrimental effect on breast-feeding practices(Reference Sobel, Iellamo and Raya13–Reference Piwoz and Huffman16).

Packaging is an important marketing tool that plays a key role in communicating relevant product information and can largely influence consumer attention at the point of sale, quality perception and purchase decisions(Reference Chambault and Burgess17). The packaging of feeding bottles and teats should include information to ensure appropriate use and enable caregivers, who have already made the decision to use bottle feeding, to make informed choices between different products. However, packages are also expected to include information that may create the idea that bottle feeding is equivalent or even superior to breast-feeding(18), as has been reported for infant formula(Reference Ergin, Hatipoglu and Bozkurt19–Reference Hernández-Cordero, Lozada-Tequeanes and Shamah-Levy21). In this sense, Dowling and Tycon reported that bottle/nipple systems are usually advertised as providing the same feeding experience as breast-feeding(Reference Dowling and Tycon22). This information has the potential undermine efforts to promote breast-feeding and may encourage mothers to rely on bottle feeding.

Feeding bottles and teats are included within the scope of the International Code of marketing of breast milk substitutes. The Code is an international policy framework to protect breast-feeding against the deleterious effect of marketing practices from manufacturers and distributors of breast milk substitutes, feeding bottles and teats(23). It was adopted in 1981 by the World Health Assembly and since then it has been updated through subsequent resolutions(24). The implementation of the Code is the responsibility of governments, who should approve national regulations to make the provisions of the Code compulsory(24,Reference Michaud-Létourneau, Gayard and Pelletier25) . As of April 2020, legal measures covering at least some of the provisions of the Code had been implemented in 136 out of 194 countries worldwide(26). This is the case of Uruguay, the Latin American country where the study was conducted(27,28) .

According to the Code, the information included on the packages of feeding bottles and teats ‘should be designed to provide the necessary information about the appropriate use of the product, and so as not to discourage breast-feeding’(23). Although the Code sets specific requirements for the labels of infant formula, such as the prohibition of including pictures of infants or texts and images that idealise their use, specific requirements for the labels of feeding bottles and teats are not included(23).

Full compliance of the provisions of the Code has proven to be challenging worldwide(26). Considering that violations of the dispositions of the Code have been frequently found on the labels of breast milk substitutes (even when specific regulations are set)(Reference Ergin, Hatipoglu and Bozkurt19–Reference Hernández-Cordero, Lozada-Tequeanes and Shamah-Levy21), a similar trend could be expected for the labels of feeding bottles and teats(18).

In this context, the aim of the present work was to analyse the information displayed on the packages of feeding bottles and teats, commercialised in Montevideo (Uruguay) with the goal of identifying key practices that may discourage breast-feeding. Special emphasis was placed on all the images or texts that imply or create the belief that bottle feeding is equivalent or superior to breast-feeding, or that idealise the use of feeding bottles and teats (e.g. images or text that represent bottle feeding as perfect or better than in reality). The analysis of the marketing practices of feeding bottles and teats that may discourage breast-feeding is highly relevant in Uruguay given the high rates of childhood overweight and obesity: 12·6 % among children younger than 5(Reference Delfino, Rauhut and Machado29).

Materials and methods

The study was conducted as part of the periodic assessment performed by the Uruguayan government to monitor the marketing of breast milk substitutes according to the NetCode toolkit(30).

Selection of retail outlets

Following the recommendations of the NetCode toolkit(30), a total of forty-four retail outlets selling breast milk substitutes were selected in Montevideo, the capital city of Uruguay. Retail outlets were selected based on two criteria: (i) proximity to thirty-three health facilities selected using probability proportional to size sampling and (ii) purposive sampling of eleven large stores(30). The pharmacy in closest proximity to each of the thirty-three health facilities was selected using GoogleMaps®. In addition, eleven retail stores, corresponding to two pharmacies, six supermarkets, two baby stores and one perfumery, were purposively sampled based on local knowledge.

Feeding bottles and teats

A spreadsheet containing a list of feeding bottles and teats was developed based on the products available in online stores. Four of the researchers who authored the present work participated as fieldworkers. They had been previously involved in similar research and were familiar with Code and the NetCode toolkit. Fieldworkers used a spreadsheet to register all the feeding bottles and teats available in each of the retail stores. All the products encountered at a store not appearing on the list were added to the spreadsheet. The procedure was repeated until no new products were found. A single item of every product was purchased. For products sold in different colours/graphic design, only the first item found in a retail store was purchased. Data collection was performed between March and June 2019.

Data analysis

After data collection was completed, the information available on the package of each of the products was analysed by two of the researchers involved in fieldwork. Images included on the products that would be visible at the moment of purchase were also included. An adaptation of the procedure proposed by the NetCode toolkit was used(30). The following information was recorded for each of the products: company name and brand, product name, importer, recommended age, language, product information printed on the package or a well-attached label (Yes/No), endorsements by a health worker or health professional body, promotional devices to induce sales of the company’s products, batch number, expiration date, instructions on how to use the product, instructions on the use of hygienic practices, images or texts that imply or create the belief that bottle feeding is equivalent or superior to breast-feeding, images or texts that idealise the use of feeding bottles and teats and statements on the superiority of breast-feeding. For each of the two categories (feeding bottles and teats), the information was extracted by one of the researchers and reviewed by another one, who checked for inconsistencies. Disagreements between the two researchers were resolved by open discussion with a senior researcher. The results were summarised using descriptive statistics.

Content analysis of the images or texts that imply or create the belief that bottle feeding is equivalent or superior to breast-feeding, as well as images or texts that idealise the use of feeding bottles and teats, was performed. Two researchers with previous experience in content analysis used inductive coding to identify categories of meaning by going through the text and the images(Reference Krippendorff31). The final categories were defined by consensus. The frequency of occurrence of each category was calculated. Examples of texts and images were selected for each category. All the analyses were performed in Spanish, and selected texts were translated for publication.

Results

A total of 197 feeding bottles and seventy-one teats were found in the retail outlets. A small proportion of the products (5 % of the feeding bottles and 8 % of the teats) did not include a label or any type of information printed on the package.

All the feeding bottles and teats had been manufactured abroad and imported into the country. Although the majority of the packages included the information in Spanish (local language in the country), 15 % of the packages of feeding bottles and 21 % of the packages of teats did not. In addition, 36 % of the packages of feeding bottles and 56 % of the packages of teats did not include the company responsible for the import. Batch number was found on approximately 70 % of the products and expiration date on approximately 50 % of the packages (Table 1).

Table 1 Information included on the packages of feeding bottles and teats commercialised in forty-four retail outlets in Montevideo (Uruguay)

* Calculated based on the information printed on the package and the information available in the booklet inside the package.

The majority of the packages included information to enable caregivers to adequately use the products. As shown in Table 1, 71–80 % of the packages included information about recommended age. Regarding instructions on how to use the product or instructions on the use of hygienic practices, the great majority of the products included the information on the package or in a booklet located inside the package. Instructions on how to use the product mainly focused on general procedures, such as not use the microwave to warm the bottle – it can heat milk unevenly and create a hot spot – to test the milk temperature (whether it is formula or breast milk) before feeding the baby, not to fill the bottle with juice or carbonated beverage and not to use the bottle as a pacifier. Safety recommendations, such as regular teats inspection to prevent a possible choking hazard, not to enlarge the existing flow opening and to regularly replace the nipple were also frequently found. On the other hand, instructions on how to choose the right teat size were scarcely found. Usage instructions related to responsive feeding were not included in any of the products.

Information about potential problems associated with bottle feeding were only present in approximately 40 % of the packages, mainly related to the potential negative effect of bottle feeding on breast-feeding, dental problems related to the introduction of the teat in sweet foods, dental problems associated with prolonged sucking, baby speech problems associated with prolonged sucking and allergies (Table 1). Finally, statements on the superiority of breast-feeding were not found on feeding bottles and found on only 4 % of the teats.

Most of the packages included some type of strategy to attract caregivers, to convey associations and to promote sales. The majority of the packages or products included images. For feeding bottles, images of animals or nature (clouds, trees, flowers, etc.) printed on the bottle were the most frequent, whereas the majority of the teat packages included images of the product (Table 1). Elements to promote sales were found on 58 % of the feeding bottles and 67 % of the teats and included promotional packs (i.e. packages of feeding bottles with pacifiers, teats, socks or tissues), cross-promotions (i.e. references to other products of the same company) and invitations to make contact using the website or social media.

Endorsements by health workers (e.g. ‘Recommended by midwives and pediatricians’, ‘Dr. Grace Yum, a certified pediatric dentist’) or organisations (e.g. International Children Medical Research Society, Institute of Child Health, Spanish Society of Pediatric Dentistry) were found in 26 % of the feeding bottles and 13 % of the teats. In addition, the packages frequently included images or text that implied or created the belief that bottle feeding was equivalent or superior to breast-feeding, or that idealised the use of feeding bottles and teats. As shown in Table 1, more than 50 % of the products include this type of information. A detailed analysis of these elements is provided in the following sub-sections.

Images or texts that imply or create the belief that bottle feeding is equivalent or superior to breast-feeding

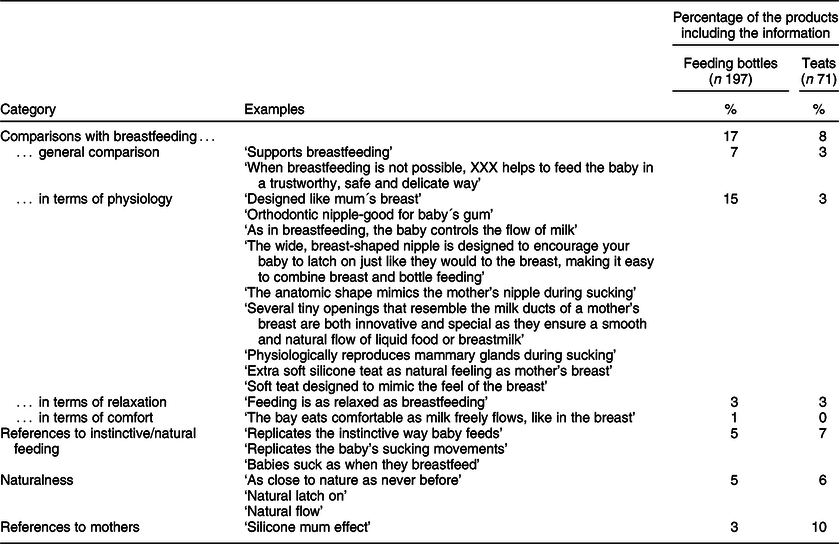

Table 2 presents an overview of the content of the images and texts found on the packages implying or creating the belief that bottle feeding is equivalent or superior to breast-feeding. Most of the images and texts compared the feeding bottles and teats with the breast, mainly in terms of physiology. Many of the statements referred to the similarity between feeding bottles and the breast in terms of shape, feeling and milk flow (Table 2). In some of the packages, the text was accompanied by images to reinforce the equivalence with breast-feeding, as exemplified in Fig. 1. The equivalence to breast-feeding was also made in terms of relaxation and comfort.

Table 2 Prevalence of different categories of images or texts that imply or create the belief that bottle feeding is equivalent or superior to breast-feeding, on the packages of feeding bottles and teats commercialised in forty-four retail outlets in Montevideo (Uruguay)

Fig. 1 Examples of three images that imply or create the belief that bottle feeding is equivalent to breast-feeding, found on the packages of feeding bottles and teats commercialised in forty-four retail stores in Montevideo (Uruguay). The image located on the bottom right side was accompanied by the text: ‘the development of the (brand blinded for publication) teat is based on the medical knowledge that a breast has several tiny milk ducts’

Other statements did not explicitly compare bottle feeding with breast-feeding but referred to the ability of feeding bottles or teats to replicate natural or instinctive feeding, their naturalness or included the expression ‘mum effect’ (Table 2).

Images or texts that idealise the use of feeding bottles and teats

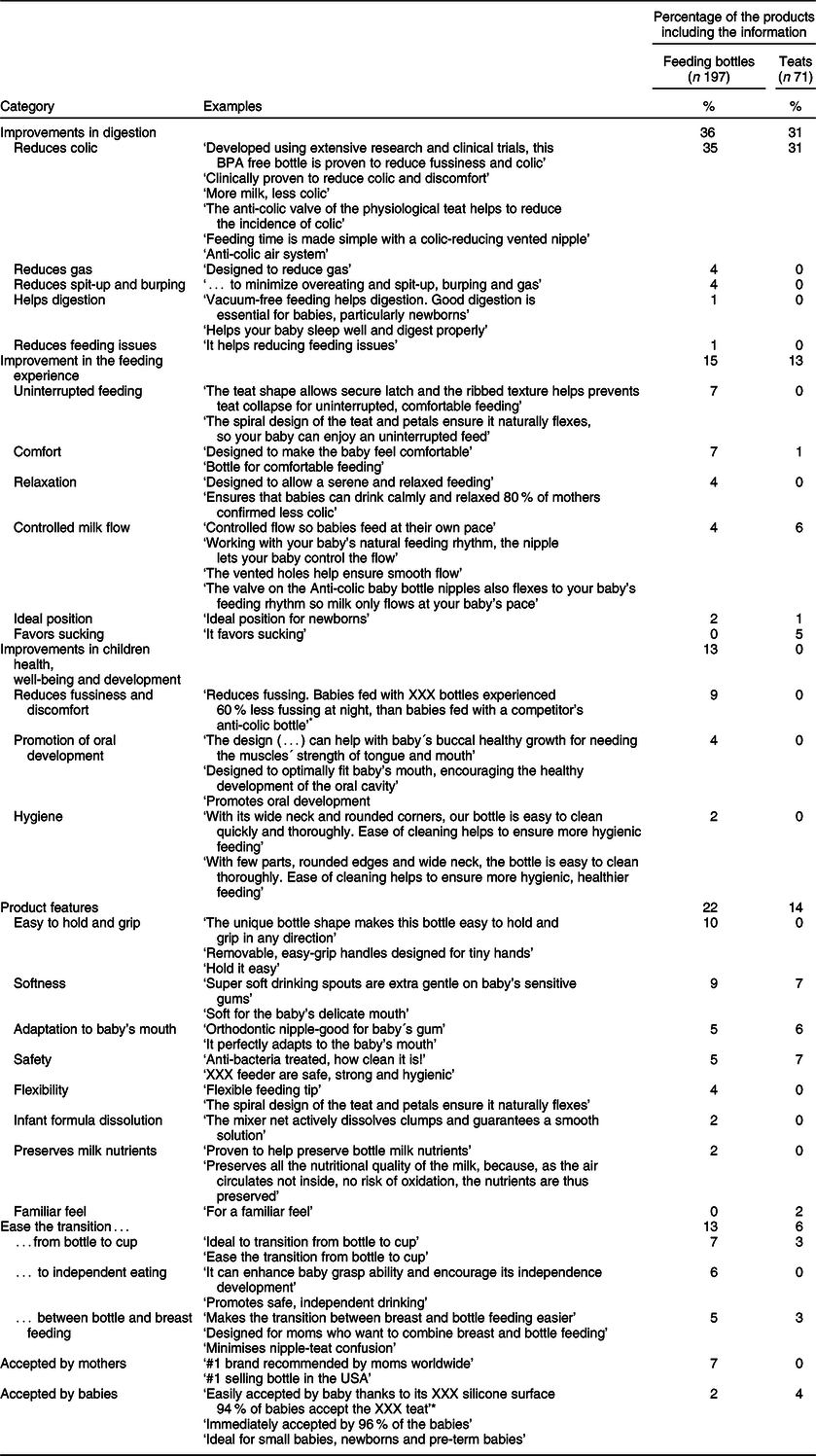

The most frequent idealisation on the use of feeding bottles and teats was related to improvements in digestion. As shown in Table 3, approximately a third of the packages of feeding bottles and teats referred to their ability to reduce colic. A small percentage of the feeding bottles also referred to reductions in gas, spit-up and burping, as well as their ability to help digestion and reduce feeding issues.

Table 3 Prevalence of different categories of images or texts that idealise the use of feeding bottles or teats, on the packages of feeding bottles and teats commercialised in forty-four retail outlets in Montevideo (Uruguay)

* Note: XXX refers to brand names or trademark names, which are not included in the article.

Improvements in the feeding experience were also mentioned on the packages, mainly uninterrupted feeding, controlled milk flow, comfort and relaxation. As shown in Table 3, the text included on the packages implied that the feeding bottles and teats were able to ‘make the baby feel comfortable’ or that they were ‘designed to allow a serene and relaxed feeding’. Some packages went further and also implied their ability to improve children’s health, well-being and development by reducing fussiness and discomfort, promoting oral development or a hygienic and healthier feeding (Table 3).

Several product features were highlighted on the packages, including easy to grip and hold, softness, adaptation to baby’s mouth, safety, flexibility, infant formula dissolution, preservation of milk nutrients and familiar feel (Table 3). Furthermore, the packages also implied that they eased the transition from bottle to cup to independent eating and between bottle feeding and breast-feeding. Finally, a small percentage of the packages also referred to mothers’ and babies’ acceptance.

Discussion

The packages of feeding bottles and teats are an important marketing tool and may be regarded as a relevant source of information for caregivers, as previously reported for infant formula(Reference Malek, Fowler and Duffy32). In this context, the present study analysed the information displayed on the packages of feeding bottles and teats, commercialised in Montevideo (Uruguay). The most salient finding of the present work was the prevalence of text and images that conveyed the idea that bottle feeding is equivalent to breast-feeding, as well as text and images that idealised the use of feeding bottles and teats. Approximately one-fifth of the packages included some type of comparison with breast-feeding, mainly in terms of the physiology of the breast and the feeding experience. This agrees with results reported by Dowling and Tycon(Reference Dowling and Tycon22). Therefore, the information included on the packages of feeding bottles and teats can create the belief that bottle feeding and breast-feeding are equivalent, which could potentially undermine efforts to promote breast-feeding. Considering that several studies have highlighted differences between bottle feeding and breast-feeding in terms of the feeding experience, intake regulation and health outcomes(Reference Bartok and Ventura5,Reference Li, Fein and Grummer-Strawn6,Reference Li, Magadia and Fein8,Reference Ventura and Mennella9) , packages of feeding bottles and teats should include information about the superiority of breast-feeding as labels of infant formula do. However, this was the case in only a minority of the packages.

The idealisation of bottle feeding was also largely present, as more than half of the packages included text or images that idealised their use. In addition, endorsements by health workers or health professional bodies were also found. The most frequent idealisation was related to improvements in digestion, particularly reduction in colic, followed by improvements in children health, well-being and development. Many of the statements included on the package made no reference to the comparator (Table 3), which suggest that they can be interpreted in relation to breast-feeding. For example, ‘Designed to make the baby feel comfortable’ or ‘Designed to reduce gas’ could be interpreted as if the feeding bottles produced better outcomes compared with breast-feeding. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that large inconsistencies between the information available on the packages of teats and actual performance have been reported(Reference Pados, Park and Dodrill33).

Although the present work was restricted to a single country, the results suggest that stricter and more detailed labelling regulations are necessary for feeding bottles and teats as misleading information is frequently included. In this sense, although the International Code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes explicitly states that the labels of infant formula should not create the belief that they are equivalent or superior to breast milk or idealise their use(23), there are no explicit standards for labelling of feeding bottles and teats. Such regulations could enable caregivers to make informed feeding choices for their infants, as well as contribute to the promotion of breast-feeding. In addition, in the specific case of Uruguay there are no clear oversight mechanisms and penalties’ regimes to guarantee enforcement of the regulations regarding feeding bottles and teats. Advancements in this respect could substantially contribute to protect children and families from inadequate marketing practices.

Almost all caregivers need to rely on bottle feeding at some point to conciliate their personal life with children’s feeding(Reference Lee10). In such situations, the characteristics of feeding bottles and teats are expected to influence the feeding experience(Reference Malek, Fowler and Duffy32). The instructions included on the packages of feeding bottles and teats should encourage appropriate feeding practices. However, results from the present work showed that a small but relevant proportion of the packages did not include any information about the product or lacked information about the recommended age for using the product, instructions on how to use the product or on the use of hygienic practices. According to the International Code of marketing of breast milk substitutes and Uruguayan regulations, the information included on the packages of feeding bottles and teats should enable an appropriate use of the products and should not discourage breast-feeding(23,28) . In addition, the instructions on how to use the product did not include references to responsive feeding or any specific recommendation on how to feed infants using feeding bottles. Similarly, previous research has identified that bottle feeding advice mainly focuses on procedural recommendations, such as cleaning procedures, correct preparation of formula and advices on how to store and transport the formula(Reference Kotowski, Fowler and Hourigan34). The inclusion of guidelines and recommendations on responsive bottle feeding on the packages can contribute to optimise health outcomes for infants, as recommended by Kassing(Reference Kassing35). In addition, it is necessary to further explore how families use feeding bottles and teats, as well as the recommendations given by health professionals regarding these products.

Strength and limitations

The key strength of the present work is its novelty. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study providing an in-depth analysis of the information displayed on the packages of such products. The high prevalence of information implying that bottle feeding is equivalent to breast-feeding or that idealised product use suggests that the topic deserves attention as a relevant factor that influences infant feeding decisions.

The present study is not free of limitations. First of all, the present reports of a single country in Latin America. Second, although the study was conducted following the recommendations of the NetCode toolkit, it was conducted in a single city and with a limited number of stores. Although further research is needed to extend results from the present work, it is important to highlight that research has shown that the marketing strategies of infant formula are largely similar across countries.

Finally, the study did not explore how caregivers understand the information included on the packages. This suggests that future studies should be carried out to explore how caregivers interpret the information available on the packages of feeding bottles and teats, as well as their social representations of bottle feeding.

Conclusion

The results from the present research showed that the packages of feeding bottles and teats commercialised in Montevideo (Uruguay) frequently included texts and images that idealise their use and create the belief that they are equivalent to breast-feeding. Considering that the International Code of marketing of breast milk substitutes does not include explicit labelling requirements for feeding bottles and teats, results suggest that stricter and more detailed regulations are necessary to end the inappropriate marketing practices on the packages of feeding bottles and teats and to enable caregivers and health professionals to make informed feeding decisions for infants.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: N/A. Financial support: Financial support was obtained from UNICEF Uruguay, Espacio Interdisciplinario (Universidad de la República, Uruguay) and Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica (Universidad de la República, Uruguay). A researcher from UNICEF Uruguay was involved in the design of the study, interpretation of the data and preparation/review/approval of the manuscript. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. Authorship: All authors contributed to the development of the research. F.A., L.A., L.V. and G.A. performed data collection and analysed the data. G.A. prepared a first version of the paper, to which all other authors then contributed substantially. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.