The nutritional transition has impacted Latin America dramatically over the past three decades(Reference Freire, Ramirez-Luzuriaga and Belmont1,Reference Rivera, Barquera and Gonzales-Cossio2) . Characterised by decreasing consumption of traditional foods, increasing consumption of ‘ultra-processed’ high-sugar, high-fat foods and increasing time spent in sedentary activities(Reference Drewnowski and Popkin3,Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng4) , these dietary shifts have led to rapid increases in the prevalence of obesity (OB) and non-communicable chronic diseases(Reference Popkin, Adair and Ng4–Reference Amuna and Zotor6). Often regarded as concentrated in urban areas, it has recently been shown that 55 % of the global rise in mean BMI from 1985 to 2017 was driven by rural populations(7,Reference Popkin8) .

The nutritional transition may be particularly abrupt when previously remote, rural communities become more connected through new road construction. These roads result in sudden market integration, as well as rapid social and ecological changes(Reference Riley-Powell, Lee and Naik9) that have extensive downstream impacts on dietary patterns and physical activity. Market integration refers to increasing production for and consumption from a market-based economy(Reference Urlacher, Liebert and Josh Snodgrass10). Market integration can reduce dependence on subsistence agriculture among rural households by increasing opportunities for commercial farming and food purchases(Reference Urlacher, Liebert and Josh Snodgrass10). These changes present both nutritional opportunities and challenges. For example, access to markets is associated with improved food security(Reference Ahmed, Liu and Bashir11) and may increase dietary diversity(Reference Koppmair, Kassie and Qaim12,Reference Stifel and Minten13) by allowing farming households to sell produce and buy foods that they cannot produce themselves(Reference Koppmair, Kassie and Qaim12). However, as agricultural production is oriented away from subsistence and towards the generation of cash income(Reference Urlacher, Liebert and Josh Snodgrass10,Reference Piperata, Ivanova and Da-Gloria14) , households increasingly depend on the formal economy to maintain food security. Markets also increase access to ultra-processed foods that negatively impact the overall quality of the diet(Reference Kolčić15) and may decrease the intake of nutrients that are disproportionately sourced from traditional dietary staples(Reference Pettigrew, Pan and Berky16). Finally, increasing market access may alter food choice through increased exposure to advertising, or because changing lifestyles alter incentives related to food preparation and the desire for convenience(Reference Seto and Ramankutty17). The net impact on nutritional status is therefore driven by the interrelated economic, ecological and social forces disrupted and altered by road development.

Most studies that examine the impact of market integration on adult health and nutrition find an association with increased adiposity(Reference Piperata, Spence and Da-Gloria18–Reference Lourenço, Santos and Orellana20) and prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors(Reference Lindgärde, Widén and Gebb21,Reference Liebert, Snodgrass and Madimenos22) . The impact of market integration on the nutritional status of children, however, is more mixed. Relative remoteness is often used as a proxy for market integration(Reference Liebert, Snodgrass and Madimenos22,Reference Minkin and Reyes-García23) , and community remoteness has in some cases been reported to increase the risk of stunting(Reference Piperata, Spence and Da-Gloria18,Reference Blackwell, Pryor and Pozo24–Reference Darrouzet-Nardi and Masters26) , while other studies have found a protective(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27) or null(Reference Stifel and Minten13) effect depending on the context. These relationships may be explained at least in part by differences in education and wealth between more- and less-remote groups(Reference Headey, Stifel and You25,Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27) . On the one hand, increasing market access strengthens the association between mother’s education and child dietary diversity(Reference Hirvonen, Hoddinott and Minten28). On the other hand, when high-quality traditional diets are replaced by high-energy, low-nutrient-dense foods, stunting and anaemia can persist despite sufficient energetic intakes(Reference Roche, Gyorkos and Blouin29).

The double burden of malnutrition, defined as the co-occurrence of OB and at least one form of undernutrition (often stunting or wasting)(Reference White, Buenrostro and Barquera30), or the ‘triple threat’ of malnutrition, represented by the co-occurrence of OB, stunting and anaemia(Reference Pinstrup-Andersen31), are a growing global concern. These co-occurrences may be present within individuals, households or populations(Reference Walrod, Seccareccia and Sarmiento32). Globally, 149 million children are stunted(33), while a third of the world’s adults are overweight (OW) or obese (OB)(Reference Ng, Fleming and Robinson34,Reference Abarca-Gómez, Abdeen and Hamid35) . Given the Sustainable Development Goals call for an end to all forms of malnutrition(36), studies have increasingly focused on understanding the environments that lead to the co-occurrence of multiple forms of malnutrition(Reference Jones, Hoey and Blesh37,Reference Turner, Aggarwal and Walls38) .

Market integration has previously been associated with a double burden of stunting and OW among children and adolescents(Reference Houck, Sorensen and Lu39,Reference Hidalgo, Marini and Sanchez40) . We extend these findings by examining trends in nutritional status through a prospective longitudinal study in rural coastal Ecuador, with data that allow individual-, household- and community-level trends to be distinguished and evaluated. We have previously shown that, from 2003 to 2013, more remote communities that were further from the nearest commercial centre had less child stunting and anaemia in this primarily Afro-Ecuadorian population, and that the burden of stunting decreased in both more- and less-remote communities over time(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27). Over the same period, the prevalence of child OW remained relatively constant at around 5 %(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27). The objectives of the present report are to examine, over the same period, the burden of adult OW and OB by time and remoteness. We treat remoteness from the commercial centre as a proxy for more limited market integration. We also examine the relationship between adult OW and OB and changes to livelihoods, household agriculture, and socio-economic status driven by market integration, and the co-occurrence of adult OW and under-five stunting and anaemia.

Methods

Study setting and context

In 1996, the Ecuadorian government started construction on a highway system connecting the northern Ecuadorian coast to the Andes. After completion of the primary highway in 2001, secondary and tertiary roads were constructed, further increasing access for previously remote communities. The ‘Environmental Change and Diarrheal Disease: A Natural Experiment’ project (EcoDess) began in 2003 as a natural experiment to document the longitudinal changes in rural communities with and without road access to the commercial centre, Borbón(Reference Eisenberg, Cevallos and Ponce41).

While the nutritional status of indigenous Ecuadorian Amazonian(Reference Lindgärde, Widén and Gebb21,Reference Liebert, Snodgrass and Madimenos22,Reference Houck, Sorensen and Lu39) and highland populations(Reference Roche, Gyorkos and Blouin29,Reference Melby, Orozco and Ochoa42,Reference Iannotti, Lutter and Stewart43) has been documented, relatively less descriptive information is available about the nutritional status of rural Afro-Ecuadorians. According to the 2012 national survey, the overall prevalence of adult OW/OB in this ethnic group was 64·4 %, compared to a national average of 62·8 %(Reference Freire, Ramirez-Luzuriaga and Belmont1). The prevalence of child undernutrition may be relatively low compared to mestizo and indigenous children living in the same towns(Reference Matos, Amorim and Campos44).

Data collection

Thirty-one communities participated in the overall study, of which 28 were included in this analysis. A detailed description of the study methods has previously been published(Reference Eisenberg, Cevallos and Ponce41,Reference Bhavnani, Bayas Rde and Lopez45,Reference Bhavnani, Goldstick and Cevallos46) . In brief, the field team visited each community in a rolling schedule over the course of 9 months. During each community visit, a census was conducted followed by a 2-week case–control study where all cases of diarrhoeal disease, in both children and adults, were identified(Reference Bhavnani, Bayas Rde and Lopez45). The order of community visits rotated over time, so that data for each community are available for both the summer and the winter seasons(Reference Kraay, Ionides and Lee47). During the first seven cycles (from 2003 to 2008) of the study, one household control and two community controls were selected for each diarrhoeal case. From cycles 8–11 (2008–2013), 10 % of all community members were selected as controls. Eleven study cycles were completed in total (approximately one every 9 months). Anthropometric data, weight and height (or length for children < 2), were measured for each case and control. In addition, anthropometry was collected for every child under 5 years of age, in every community, regardless of whether they participated in the case–control study(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27). To account for the case–control sampling scheme, we applied sampling weights to all analyses of adult OW/OB, using the sampling weights previously reported by Bhavani et al(Reference Bhavnani, Goldstick and Cevallos46). In analyses conducted at the household level (e.g. trends in household agricultural diversity), we also calculated household-level sampling weights to account for the probability of at least one individual in the household being selected into the case–control study. The method of calculation of both individual- and household-level sampling weights is reported in Appendix 2.

Outcome variables

Adult OW/OB: Anthropometric data from non-pregnant adults (>= 18 years old) were examined for extreme values, and outlier heights (defined as greater than four standard deviations from the population mean) were excluded(Reference Welch, Peterson and Walters48). BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared. Adults were categorised as underweight, normal, OW and OB, based on their BMI values (< 18·5, 18–24·9, 25–29·9, and 30 and above) and further dichotomised as underweight and normal v. OW/OB. As in previous analyses of these data(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27), three communities populated primarily by people of indigenous Chachi ethnicity were excluded due to limited data over the study time period. Because adult anthropometry was collected as part of a case–control study of diarrhoea, we tested whether any differences were observed in mean BMI or the prevalence of OW/OB and OB between adult cases and controls. No statistically significant differences were observed and therefore, both cases and controls were included in all subsequent analyses.

Child stunting was defined as a height-for-age less than two Z-scores below the WHO standard(49). Observations with height-for-age Z-scores less than –6 or greater than +6 were excluded(50). Children from 0 to 5 years of age who were also enrolled as cases tended to have lower length or height-for-age and were more likely to be anaemic. Because length-for-age is an indicator of chronic malnutrition and is therefore a result of prior, rather than current, diarrhoeal disease, the length-for-age Z-score for children under 24 months of age, and height-for-age Z-score of children 24–60 months of age (LAZ/HAZ) of children with diarrhoeal disease during the case–control study was included when estimating the prevalence of households with concurrent OW/OB and child stunting.

Child anaemia was defined as Hb concentrations less than 11·0 g/dl in children from 6 to 59 months of age(51). Because Hb concentrations are influenced by inflammation, only anaemia measurements from children who did not have diarrhoeal disease during the case–control study were included in examining the co-occurrence of OW/OB and child anaemia.

Exposure variables

Remoteness

To define relative community remoteness, we used an index previously developed for the study based on total travel time and cost between the village and Borbón. To develop this score, repeated measurements of each variable (travel cost and travel time) were documented through trips undertaken by available public transportation. If multiple modes of travel were required to complete a trip, for example, travel by both bus and boat, the cumulative travel cost and time were used. The average total travel time and cost for each village were then standardised by converting them to Z-scores

![]() $\left( {{{travel\;time\;to\;villag{e_i} - mean\;travel\;time} \over {standard\;deviation\;of\;travel\;time}}} \right)$

, and the two Z-scores were summed to generate a final score(Reference Kraay, Trostle and Brouwer52). In our analysis, we used a categorical form of this remoteness score(Reference Kraay, Trostle and Brouwer52). ‘Near’ and ‘medium’ communities correspond to the first and second quartile, while ‘far’ communities correspond to the combined third and fourth quartiles(Reference Eisenberg, Cevallos and Ponce41). These categories correspond approximately to mode of transportation, as 6 of 7 communities with direct road access were categorised as ‘near’, while 26 of 27 communities without road access (i.e. only accessible by river travel, or only through a combination of road and river travel) were categorised as ‘medium’ or ‘far’.

$\left( {{{travel\;time\;to\;villag{e_i} - mean\;travel\;time} \over {standard\;deviation\;of\;travel\;time}}} \right)$

, and the two Z-scores were summed to generate a final score(Reference Kraay, Trostle and Brouwer52). In our analysis, we used a categorical form of this remoteness score(Reference Kraay, Trostle and Brouwer52). ‘Near’ and ‘medium’ communities correspond to the first and second quartile, while ‘far’ communities correspond to the combined third and fourth quartiles(Reference Eisenberg, Cevallos and Ponce41). These categories correspond approximately to mode of transportation, as 6 of 7 communities with direct road access were categorised as ‘near’, while 26 of 27 communities without road access (i.e. only accessible by river travel, or only through a combination of road and river travel) were categorised as ‘medium’ or ‘far’.

Livelihoods

‘Rural’ occupations were defined as jobs involving agriculture (including working one’s own farm or working on a palm plantation), harvesting of forest products, logging and raising animals. ‘Urban’ occupations were defined as cooking for others, working for the government, small business owner, teacher or ‘worker’ (i.e. employee). Jobs that were not defined as either ‘urban’ or ‘rural’ included homemaker, artisan, student, unemployed, retired or other.

Socio-economic status was captured via adult education (highest year of schooling completed); household construction (an index of housing materials that has previously been validated in the region(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27)) and a wealth index (aggregate ownership of assets(Reference Lee, Whitney and Blum53)).

Agricultural practices

If households reported cultivating land in the past year, they were then asked to enumerate crops grown in the past year. Agricultural diversity was defined as the total number of crops reported (range: 1–14). The primary use for farm products (consumption, sale or both) was based on the question, ‘What do you do with your harvest?’.

Statistical analysis

Differences between communities in weighted mean age and education, and the weighted prevalence of OW/OB, and other factors were examined using adjusted Wald tests. Weighted Pearson’s χ 2 tests were used to examine differences in multiple nutritional burdens between households.

To estimate trends in OW/OB and OB over time and by community remoteness, we used weighted logistic regression models with a clustered sandwich estimator to adjust for subjects present within multiple cycles and accounted for probability of sampling using inverse probability weights. The prevalence of OW/OB and calendar time in the model varied by sex, as the prevalence of OW/OB increased more rapidly among men than among women; therefore, models were stratified by sex. A random effect was included to account for multiple measurements from the same individual in different years. Models of agricultural diversity were run separately and included land-owning households only.

To test whether factors related to increasing market integration drove trends in OW/OB, we first used weighted multinomial regression models to examine trends over time in the reporting of ‘rural’ and ‘urban’ job types, as well as to examine the prevalence of households without a working farm, or with a farm primarily geared towards the sale, sale and household consumption, or household consumption of crops. Among farming households, we also used linear regression models to examine trends in agricultural diversity over time.

We then constructed models to examine the association between remoteness and OW/OB. Our specific variables of interest were the job type of the individual (rural or urban) and whether the household had a working farm, and our outcome of interest was OW/OB. We also considered adjustments for the age, sex, years of education and ethnicity (Afro-Ecuadorian or mestizo) of the participant, as well the wealth of the household. Final multivariable models were constructed based on inclusion of variables significant in bivariate models at the P <= 0·15 level as well as overall model fit. We used mixed-effects Poisson models that accounted for probability of sampling and included random intercepts at the household and individual level. Following our prior approach(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27), we also examined whether livelihoods and socio-economic status mediated the relationship between OB/OW and remoteness by examining whether the inclusion of these variables in the model resulted in a reduction in the magnitude of regression coefficient for remoteness. Similar models were also constructed that included adults in farming households only and tested the impact of agricultural diversity on adult OB/OW. As a sensitivity analysis, we also tested the impact of agricultural diversity on adult OB/OW among the subset of agricultural households that reported owning their land.

To examine the co-occurrence of adult OW and child undernutrition, we conducted analyses at the individual, the household and the community level. At the individual level, we constructed mixed-effects Poisson models to examine whether adult livelihoods, land ownership and agricultural diversity were associated with child stunting and child anaemia. In these models, we adjusted for child age, sex, household size, highest level of education of any adult in the household, relative remoteness and household wealth (asset score). The associations between child stunting, relative community remoteness and socio-economic status have previously been reported(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27).

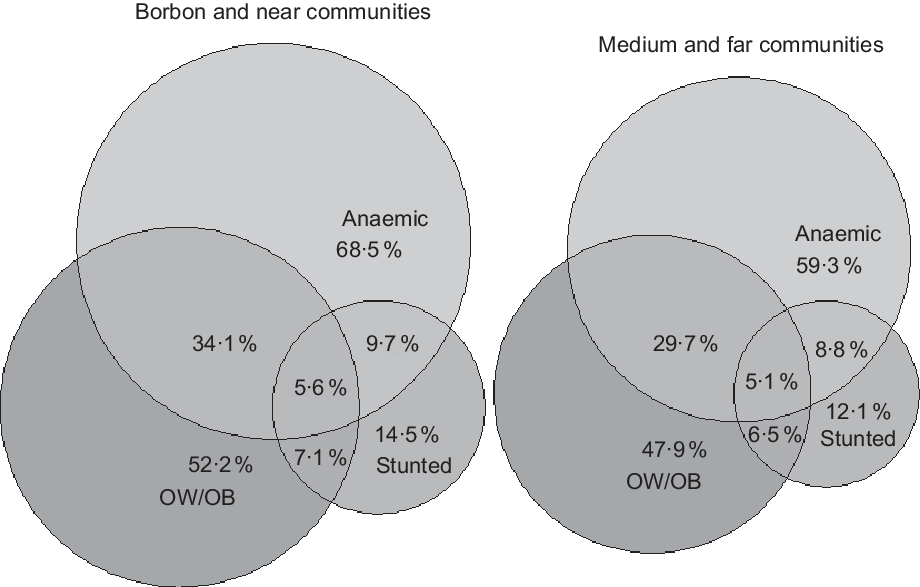

At the household level, we examined the association between adult OW and OB and the presence of a stunted or anaemic child in the same household. We restricted our analyses to adults living in households with a child under 5 years of age. When multiple children under 5 years of age were present in the household, we considered only the youngest. We created Venn diagrams to visualise the co-occurrence of adults who were OW or OB, and children who were stunted or anaemic. These were constructed separately for Borbón and less remote communities, v. medium and far communities. At the community level, we calculated the Spearman’s correlation between the overall prevalence of OW or OB adults over the study period, and the overall prevalence stunting among children under 5 years of age.

All analyses were performed in Stata version 15.1.

Results

From 2003 to 2013, 2176 anthropometric measurements were collected from 199 case and 1977 control adult study participants (1665 unique individuals) and 4608 children under 5 years of age (2618 unique individuals). After excluding pregnant women and measurements where heights or weights were improbable or extreme (greater or less than four standard deviations of the population distribution), the final sample included 2053 observations from 1558 unique adult individuals. Weighted and unweighted characteristics of this group are reported in Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1, respectively. Measurements from 4170 observations from 2395 unique children under 5 years of age were also retained (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2).

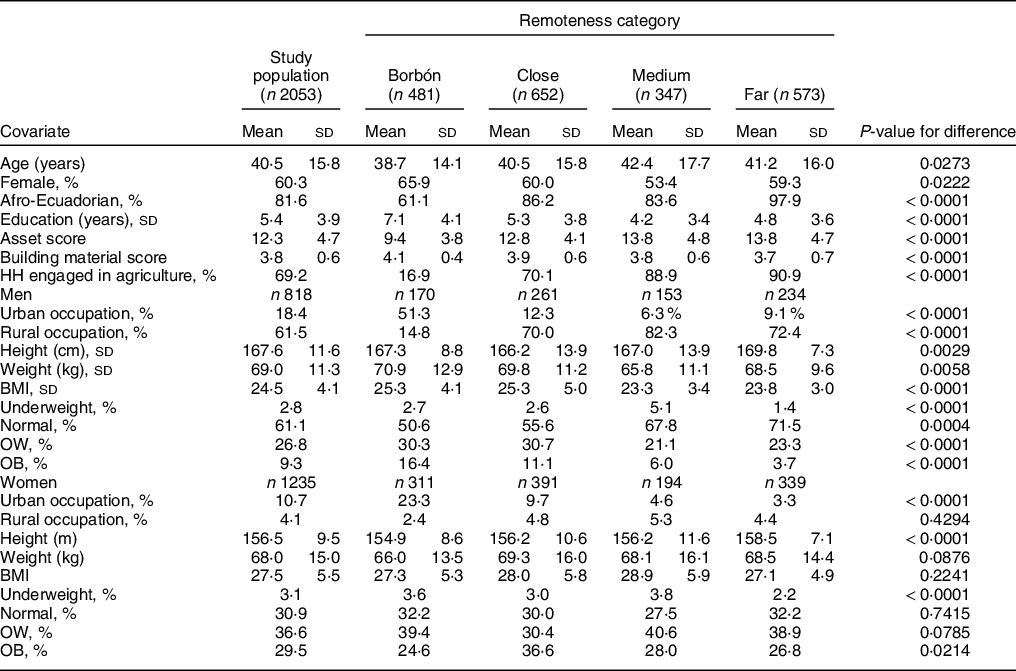

Table 1 Weighted study population characteristics

OW, overweight; OB, obesity.

Trends in overweight/obesity and obesity over time and by community remoteness

Most characteristics, including mean adult age, height and years of education, varied by remoteness category. Community remoteness was positively associated with adult height and inversely associated with adult weight among men but not women (Table 1). The percentage of the population that identified as Afro-Ecuadorians increased with community remoteness from 61·1 % in Borbón to 97·9 % (Table 1). In total, 15·3 % of the study population was mestizo, with this group primarily residing in Borbón.

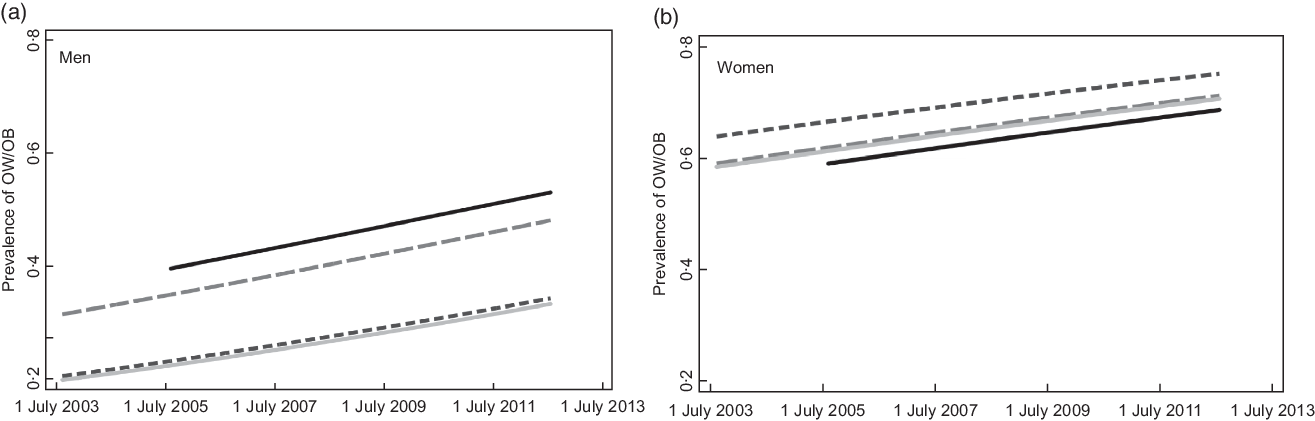

The overall weighted prevalence of OW and OB throughout the study was 26·5 % and 36·0 %, respectively, for men, and 36·0 % and 29·9 % for women. Among men, OW/OB increased from 25·1 % to 44·8 % from 2003 to 2013 and was least common in the most remote communities. Among women, OW/OB increased from 59·9 % to 70·2 % from 2003 to 2013 and was not associated with community remoteness (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Fig. 1 Trends in adult overweight or obesity are shown over chronological time, according to remoteness category. ![]() Bordon;

Bordon; ![]() close;

close; ![]() medium;

medium; ![]() far. OW/OB, overweight or obese

far. OW/OB, overweight or obese

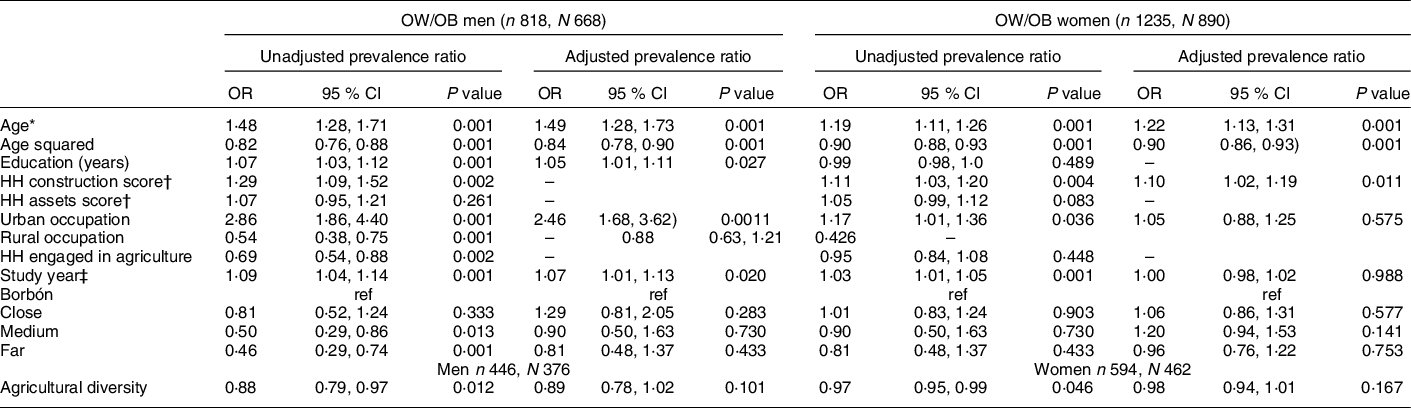

Table 2 Risk factors for overweight or obesity based on unadjusted and adjusted Poisson’s models

OW, overweight; OB, obesity.

* Per 10 years of age, centred at 40 years.

† Building and HH asset scores are expressed per standard deviation.

‡ Per year, centred at study midpoint (March 2008).

Association between factors related to increasing market integration, and nutritional status of adults and children

Over the decade-long study period, the proportion of men reporting rural livelihoods (primarily agriculture) diminished. In contrast, most women (> 70 %) reported ‘homemaker’ as their primary livelihood across the study period (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Figure 1 and Table 1).

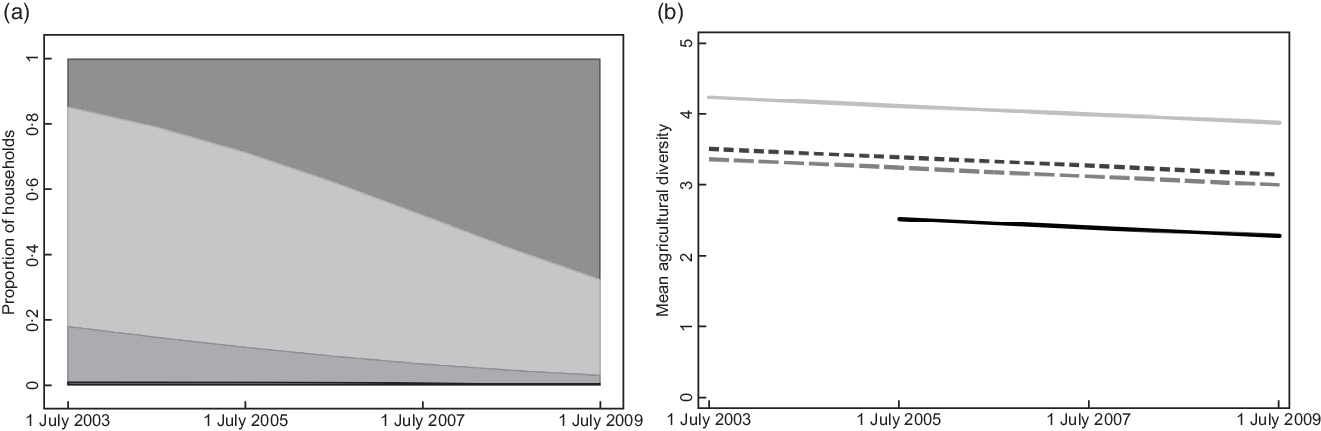

In multivariable models, urban occupation was positively associated with OW/OB among men, after adjusting for age, sex, education, asset scores and building scores. Also in men, the relationship between greater remoteness and a lower prevalence of OW/OB was attenuated when urban livelihoods were included in the model, suggesting that the higher prevalence of urban livelihoods in less remote communities partially explained the higher prevalence of male OW/OB. Among households engaged in agriculture, 93 % reported owning the land they cultivated. Within these agricultural households, the proportion of households to sell increased over time, while agricultural diversity gradually decreased (Fig. 2). Agricultural diversity was protective against adult OW/OB (Table 2). This association remained consistent when restricted to only those agricultural households that also owned their land (in men: OR: 0·88, 95 % CI: 0·80, 0·98 and in women: OR: 0·97, 95 % CI: 0·94, 1·00). Among children, neither adult livelihoods nor agricultural diversity were associated with stunting or anaemia (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 3).

Fig. 2 Estimated trends during the first half of the study (2003 to 2009), across all study communities, in household agriculture (a); ![]() to sell;

to sell; ![]() to eat;

to eat; ![]() to sell and eat;

to sell and eat; ![]() no agriculture, and agricultural diversity among households engaged in agriculture (b).

no agriculture, and agricultural diversity among households engaged in agriculture (b). ![]() Bordon;

Bordon; ![]() close;

close; ![]() medium;

medium; ![]() far

far

Co-occurrence of child stunting, child anaemia and adult overweight or obesity

Of the 2053 adult anthropometry measurements collected, 708 were collected from an adult living in a household with at least one child under 5 years of age at the time of the measurement. After excluding child cases, 404 measures were collected from an adult in a household with a child for whom a Hb measurement was available. In total, 15·4 % of children living with a non-OW, non-OB adult were stunted, compared to 12·9 % living in a house with an OW/OB adult (adjusted Wald test P = 0·42). Similarly, 64·8 % of children living with a non-OW, non-OB adult were anaemic, compared with 63·3 % of children living in a house with an OW/OB adult (P = 0·79). In adjusted models, there was no evidence that having a stunted on anaemic child in the household was associated with risk of adult OW/OB, compared to having a non-stunted or non-anaemic child in the household (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 4).

As previously reported(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27), the prevalence of child stunting decreased over time, while the prevalence of child anaemia remained constant (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 3). Combining these trends with the increase in adult OW/OB, we found that the prevalence of households with both adult OW/OB and child stunting remained constant over time (5·9 % (95 % CI: 2·5 %, 13·4 %) from 2003 to 2007 v. 7·2 % (95 % CI: 4·2 %, 12·1 %) from 2008 to 2013, P = 0·7002). On the other hand, the prevalence of households with both adult OW/OB and child anaemia increased (22·7 % (95 % CI: 15·4, 32·2 %) in 2003–2007 to 35·7 % (95 % CI: 29·6 %, 42·4 %) from 2008 to 2013, P = 0·0163). The distributions of adult OW/OB and child stunting in the population were not statistically significantly different by community remoteness (weighted Pearson’s χ 2 test statistic P = 0·3123), while the distribution of adult OW and child anaemia was statistically greater in Borbón and near communities (weighted Pearson’s χ 2 statistic P = 0·0338). Aggregated over the study period, in Borbón and near communities, 9·4 % (95 % CI: 5·9 %, 14·7 %) of households had no nutritional burdens present, while 51·0 % (95 % CI: 43·2 %, 58·7 %), 34·0 % (95 % CI: 27·0 %, 41·7 %) and 5·6 % (95 % CI: 2·8 %, 10·9 %) had one, two and three burdens present, respectively. In medium and far communities, 20·5 % (95 % CI: 14·9 %, 27·5 %) of households had no burden present, and 44·7 % (95 % CI: 37·1 %, 52·7 %), 29·6 % (95 % CI: 22·9 %, 37·4 %) and 5·1 % (95 % CI: 2·4 %, 10·4 %) had one, two and three burdens present (weighted Pearson’s χ 2 statistic for overall difference P = 0·0608, Fig. 3), respectively. The most common double burden observed was adult OW/OB and child anaemia.

Fig. 3 Estimates of multiple nutritional burdens by relative remoteness based on all study years combined. OW, overweight; OB, obesity

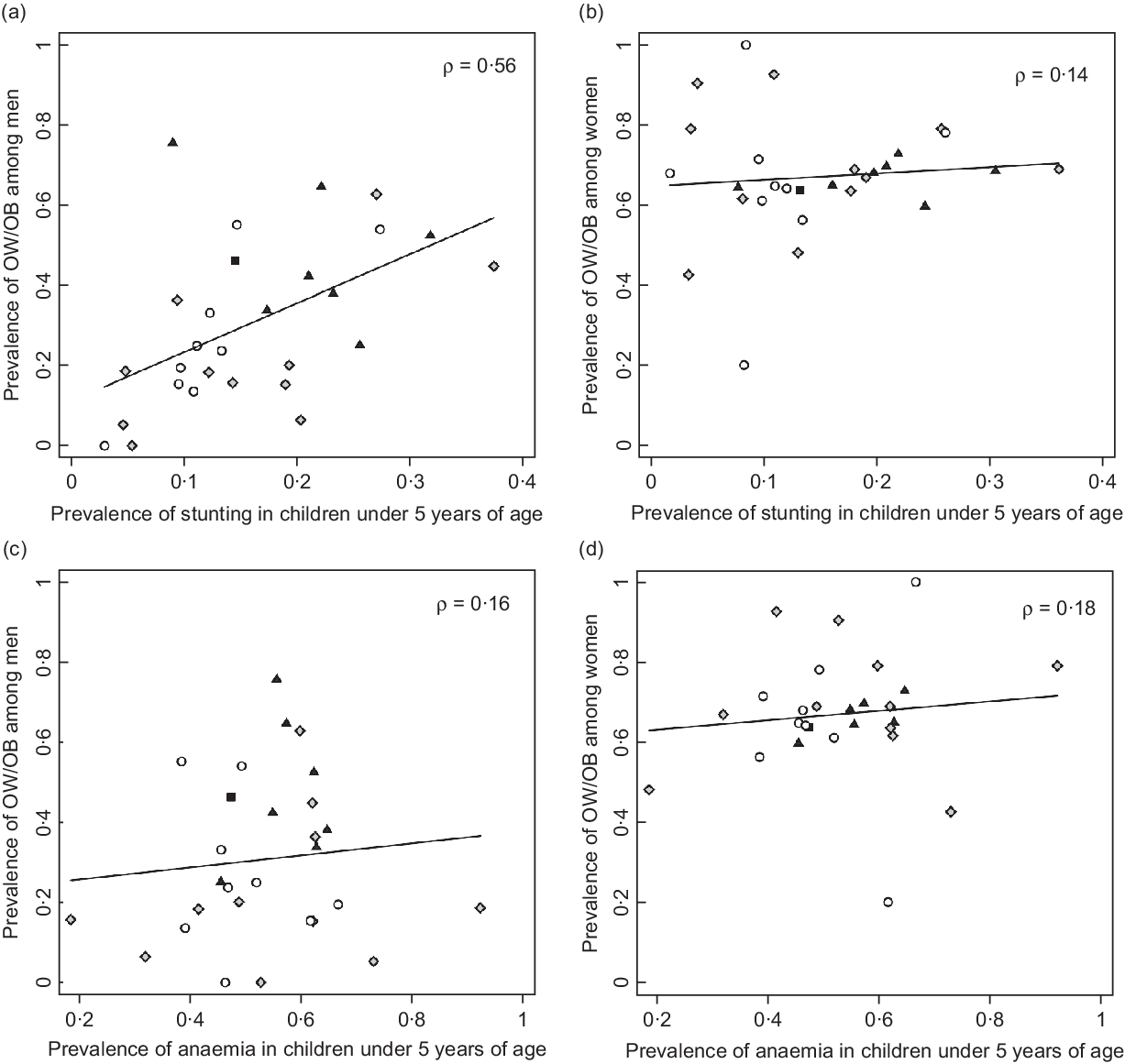

Communities where the prevalence of OW/OB was higher among men also tended to be communities with a higher prevalence of child stunting (Spearman’s ρ = 0·56, P = 0·0018) but not child anaemia (Spearman’s ρ = 0·14, P = 0·4900). There was no association between the prevalence of OW/OB among women and child stunting and anaemia (Spearman’s ρ = 0·16, P = 0·40 and Spearman’s ρ = 0·1800 and P = 0·3500, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 (a–d) Weighted estimates of the prevalence of adult OW/OB and child stunting averaged across the study period. Spearman’s correlations (ρ) are reported. Communities with a higher prevalence of OW/OB among men also tended to have more child stunting. ![]() Bordon;

Bordon; ![]() close;

close; ![]() medium;

medium; ![]() far. OW, overweight; OB, obesity

far. OW, overweight; OB, obesity

Discussion

We observed an increasing prevalence of OW and OB among Afro-Ecuadorian adults from 2003 to 2013 (25-44 % for men and 60-70 % for woman), a period when the expansion of road networks precipitated rapid change in the region. Because our data were collected from a case–control study, our analysis used weighting to estimate the community-level prevalence of OB in these relatively rural study communities. While the burden of OW/OB in these communities was below the previously estimated overall national prevalence of OW/OB among all men (both urban and rural) during the same period (60·0 % in 2012), it surpasses the national prevalence among women (65·5 % in 2012), as well as the overall prevalence among Afro-Ecuadorians women specifically (64·4 % in 2012)(Reference Freire, Ramirez-Luzuriaga and Belmont1). This result is notable given that our population was both rural and remote: 20 of the 28 communities included in our study were only accessible by boat at the time of data collection, and the predominant livelihood remained agriculture throughout the study period.

In the same communities and over the same period, the prevalence of stunting in children under 5 years of age decreased(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27). Notably, anaemia persisted. Synthesising these results with the trends in adult OW/OB, we find that multiple burdens of malnutrition (OW or OB in adults and stunting and anaemia in children) were most prevalent in communities with road access. These differences between communities with and without road access were statistically significant for the co-occurrence of OW/OB and anaemia, but not for the co-occurrence of OW/OB and stunting. This comparative analysis was limited to a subset of data where paired measurements were available for adults and children from the same household. In a prior analysis of all anthropometric data from children under 5 years of age, community remoteness was negatively associated with stunting(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27). Despite these community-level associations, we found no evidence for the clustering of adult OW and child stunting or anaemia at the household level. This is not surprising, as adult education and wealth were both risk factors for OW, and protective against stunting(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27). Similar clustering in nutritional burdens at the state or district scale but not household scale has been reported in other settings(Reference Varghese and Stein54). Overall, these results suggest that, in our setting, multiple burdens of malnutrition are driven by community-level processes and mediated by household-level risk factors.

We are limited by a lack of data to characterise proximal risk factors for overnutrition such as measures of dietary intake and physical activity. Notably, however, the association between community remoteness and OW/OB in men was attenuated when urban livelihoods were included in the model, suggesting that the higher prevalence of urban livelihoods in less remote communities mediated the inverse remoteness – OW/OB relationship. Reduced physical activity associated with more sedentary occupations has been shown to explain differences in OW/OB between rural and urban communities in other parts of the world(Reference Ntandou, Delisle and Agueh55). OW/OB among women also increased substantially over the same period (by 10 % v. 19 % in men), without concurrent changes in reported livelihoods. Women often assist in agriculture without reporting it as their primarily livelihood, so it may be that physical activity also declined in this group over the same period. Alternatively, changes in the food environment, such as features related to the availability, affordability and quality of foods in wild, cultivated and built spaces(Reference Downs, Ahmed and Fanzo56) may have driven changes in diet that we are unable to characterise directly here.

We are also limited by a lack of information about early child feeding practices that may explain declines in stunting, without concurrent declines in anaemia, over the same period. Both the 2012 and 2019 ENSANUT surveys report that more than 70 % of Ecuadorian infants under 6 months of age consume liquids other than breast milk, while young child feeding practices continue to be characterised by lower-than-optimal dietary diversity(Reference Freire, Ramirez-Luzuriaga and Belmont1,57) and low nutrient density, particularly for Fe(Reference Roche, Gyorkos and Blouin29,Reference Huiracocha-Tutiven, Orellana-Paucar and Abril-Ulloa58) . Increased market access may have reduced severe food insecurity(Reference Riley-Powell, Lee and Naik9) and increased energetic adequacy, which is a minimal but not sufficient condition for improved child growth(Reference Griffen59). However, it is unclear how these changes impacted dietary quality for young children. Increased market access may have increased access to fruits and vegetables(Reference Riley-Powell, Lee and Naik9), but possibly also to processed and ultra-processed foods. Decreases in child stunting are also likely to have been driven by community-level improvements in sanitation access over the study period(Reference Fuller, Villamor and Cevallos60).

We also observed that market integration may have driven increases in commercial agriculture and reduced agricultural diversity. Although we observed no association between agricultural diversity and child undernutrition, agricultural diversity was protective against adult OW/OB. Agricultural development programmes have been proposed to address multiple burdens of malnutrition, but programmes that support local agricultural diversity and production should also consider the indirect impacts of wildlife depletion on household food choices. In northern coastal Ecuador, international conservation efforts have focused on the promotion of biodiversity-friendly cacao production(Reference Waldron, Justicia and Smith61), an approach that may preserve habitats for some animal species(Reference Schulte-Herbrüggen, Cowlishaw and Homewood62).

Our analysis relies on a previously constructed ‘remoteness’ index based on travel time and costs, as a proxy for relative market integration. This proxy has been used by others(Reference Liebert, Snodgrass and Madimenos22,Reference Minkin and Reyes-García23) . While many characteristics, including education, asset and building material scores, household engagement in agriculture and rural v. urban status, increased or decreased consistently along this gradient, we also observed some inconsistencies such as a non-statistically significant trend towards higher mean BMI among women in ‘medium’ as compared to ‘near’ and ‘far’ communities. We are limited by the lack of a more direct measure of market assess, as well as a lack of data on physical activity and dietary intake, as described above. It is also notable that socio-economic status, as represented by household asset scores but not building materials, was highest in the more rural communities. We used an asset scores that had been previously developed by the study team through qualitative research and included a combination of rural and urban assets. However, it is possible that rural assets were relatively over-represented in this score. Differences in mean scores between communities should therefore be interpreted with caution. The inclusion of the score is useful nevertheless, as it provides comparability to prior analyses(Reference Lee, Whitney and Blum63). We are also limited insofar as this study was designed to investigate enteric pathogen transmission dynamics, rather than changes in nutritional status over time(Reference Eisenberg, Cevallos and Ponce41). Because adult anthropometry was collected as part of a diarrhoeal disease case–control study, paired adult and child anthropometry from the same household was somewhat limited. On the other hand, a counterbalancing strength of the study is the presence of continuous data over a decade, describing an under-represented population.

A final, notable limitation is the lack of baseline anthropometric data prior to the construction of the road in 1996. The EcoDess study was conceived as a ‘natural experiment’ that aimed to quantify the impact of road construction on previously similar rural communities. The path of the road was decided without community input, and thus, was essentially a random process, impacting some communities and not others(Reference Eisenberg, Cevallos and Ponce41). As a result, multiple prior analyses have treated road construction as a ‘quasi-randomised intervention’, assuming that any differences between communities can primarily be explained by this event(Reference Eisenberg, Cevallos and Ponce41). While most reports from other parts of the world suggest that community remoteness is a risk factor for stunting(Reference Piperata, Spence and Da-Gloria18,Reference Blackwell, Pryor and Pozo24–Reference Darrouzet-Nardi and Masters26) , a previous analysis of this dataset documented that, in our study site, living in a more remote community was protective against child stunting(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27). In prior publications, differences in sanitation coverage(Reference Fuller, Villamor and Cevallos60), and enteric pathogen transmission(Reference Bhavnani, Bayas Rde and Lopez45), as well as socio-economic factors and potentially access to animal-source foods in the form of fish, have been explored to explain this finding(Reference Lopez, Dombecki and Trostle27,Reference Fuller, Villamor and Cevallos60) . However, in examining anthropometry from adults as well as young children, we note that adults in the most remote communities were taller, by an average of 2–3 cm, than adults in ‘near’ communities or in Borbón. Adult height is considered an important indicator of childhood circumstances(Reference Webb, Kuh and Peasey64). All adults in the study were born before the construction of the road, and only the very youngest adults were toddlers in 1996. This trend suggests possible qualitative differences between the communities prior to road construction, such that adults living in communities that remained ‘remote’ were likely already healthier as children than adults in communities that became ‘less remote’ as a result of road construction. These advantages may then have been conferred to the next generation.

Communities that experience rapid market integration may be at particularly high risk of multiple forms of malnutrition. However, periods of sudden transition may also represent critical windows for intervention if they are timed to influence longer-term community trajectories. To successfully address multiple burdens of malnutrition, ‘double-duty’ actions that aim to simultaneous address adult OW/OB and child undernutrition should be advocated(Reference Hawkes, Ruel and Salm65). Strategies aimed at individual- or household-level behaviour change should also be paired with approaches that target the food system, which in this context may include the promotion of agricultural diversity. Other potentially important community- or regional-level processes include modifiable social and economic pathways through which market integration impacts diet.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Denys Tenorio and Mauricio Ayovi of Ecología, Desarrollo, Salud y Sociedad (EcoDess) project research team for their contributions to previous data collection. Financial support: This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01-AI050038]. Conflict of interest: No. Authorship: GOL and CG were responsible for project conception, data analysis, interpretation of data and drafting of the article. NMC, WC and JNSE contributed to the study design, conducted data collection, interpreted data and critically revised the article. ADG interpreted data and critically revised the article. GOL and JNSE shared primary responsibility for final content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Michigan and the Universidad San Francisco De Quito Bioethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020004462