Obesity prevalence among adolescents in Canada has tripled over the past 25 years. In 2004, an estimated 26 % of Canadian children and adolescents aged 2 to 17 years were overweight or obese, and 8 % were obese(Reference Shields1). Excess body weight negatively impacts self-esteem, social and cognitive development(Reference Reilly, Methven, McDowell, Hacking, Alexander, Stewart and Kelnar2), and leads to a spectrum of co-morbidities including type 2 diabetes, CVD and multiple cancers that reduce quality of life, life expectancy, and cost billions of dollars in health-care spending(Reference Must and Strauss3–Reference Katzmarzyk and Janssen5). Multiple cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown that increased television viewing is associated with an increased risk of obesity in children(Reference Crespo, Smit, Troiano, Bartlett, Macera and Andersen6–Reference Caroli, Argentieri, Cardone and Masi10). Except sleep, children spend more time watching television than doing any other single activity(Reference Dietz and Strasburger11).

Several mechanisms may underlie the positive association between television viewing and obesity. Television watching is sedentary and replaces more vigorous activities, leading to a decline in energy expenditure(Reference Caroli, Argentieri, Cardone and Masi10). Another suggested mechanism is the influence of food advertisements on food choices and nutrition. The majority of foods featured in advertisements targeted at children are inconsistent with dietary recommendations(Reference Kotz and Story12) and tend to be energy-dense, high in fat and/or sugar(Reference Harrison and Marske13–Reference Ostbye, Pomerleau, White, Coolich and McWhinney15). Observational studies and randomized controlled trials have shown that such advertisements increase children’s preference for the advertised foods(Reference Borzekowski and Robinson16, Reference Dixon, Scully, Wakefield, White and Crawford17). Television viewing also provides the opportunity to snack(Reference Matheson, Killen, Wang, Varady and Robinson18–Reference Dubois, Farmer, Girard and Peterson20), which may increase energy intake(Reference Gore, Foster, DiLillo, Kirk and Smith West21). In addition, eating meals in front of the television instead of with the family in a structured setting diminishes the nutritional and psychosocial benefits of family meals(Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald22–Reference Feldman, Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer and Story24).

Previous studies have reported that increased television watching correlates with higher intakes of sugar-sweetened soft drinks, snacks and fast foods, and lower intake of fruit and vegetables, in school-aged children(Reference Wiecha, Peterson, Ludwig, Kim, Sobol and Gortmaker25–Reference Lowry, Wechsler, Galuska, Fulton and Kann28) and in children as young as 3 years old(Reference Miller, Taveras, Rifas-Shiman and Gillman29). Similarly, studies have reported that the diets of children who eat meals in front of the television include more soft drinks and less fruit and vegetables(Reference Feldman, Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer and Story24, Reference Fitzpatrick, Edmunds and Dennison30–Reference Marquis, Filion and Dagenais32). However, very few studies have addressed whether the effect of eating meals during television viewing is over and above that of the overall time spent television watching. The two studies on whether the effect of eating meals during television viewing on body weights is over and above the effect of overall time spent television watching came to seemingly contradictory conclusions(Reference Thomson, Spence, Raine and Laing19, Reference Dubois, Farmer, Girard and Peterson20). A better understanding of the independent importance of television watching and eating while watching television is essential to directing new public programmes to promote healthy eating and to prevent obesity.

The present study examines the associations of television viewing and eating while viewing television with children’s diet and body weights. This research includes a large population-based sample of grade 5 students in Nova Scotia, a Canadian province where poor nutrition and excess body weight are particularly pronounced(Reference Katzmarzyk and Ardern33, Reference Willms, Tremblay and Katzmarzyk34).

Methods

Study design/setting

The 2003 Children’s Lifestyle and School Performance Study (CLASS) was a population-based survey of grade 5 students and their parents in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia(Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald22). The study included a questionnaire that was completed at home by parents along with an informed consent form consenting to their child’s participation. This questionnaire collected information on sociodemographic factors and contained validated questions on their child’s activities including the number of hours of watching television, taken from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth(35). This questionnaire asked the usual number of hours their grade 5 child spent watching television. The response categories were: never or <1 h/d; 1–2 h/d; 3–4 h/d; ≥5 h/d.

The study also included a slightly modified version of the Harvard Youth/Adolescent Food Frequency Questionnaire (YAQ)(Reference Rockett, Wolf and Colditz36) that was administered to the students in the schools by study assistants. The YAQ is a validated 147-item instrument that is suitable for grade 5 students who are primarily 10 or 11 years of age(Reference Rockett, Wolf and Colditz36). One of the YAQ questions is on the frequency of having supper in front of the television. Responses were: never or <1 time/week; 1–2 times/week; 3–4 times/week; ≥5 times/week.

Based on the responses to the YAQ and the Canadian Nutrient Files, we calculated students’ nutrient and energy intakes. To characterize students’ diet, we used nutritional indices that have been associated with increased or decreased risk for obesity and chronic diseases(Reference Willett37, Reference Astrup, Dyerberg, Selleck and Stender38). These were: consumption of (non-diet) soft drinks (binary, ≥2 servings/week v. <2 servings/week); percentage energy intake from sugar out of total energy from carbohydrate (continuous); percentage energy intake from fat (continuous); percentage energy intake from snack food (continuous); daily servings of fruits and vegetables (continuous); and the Diet Quality Index (continuous, on a scale from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating highest diet quality). The Diet Quality Index is a composite measure which encompasses dietary variety, adequacy, moderation and balance(Reference Kim, Haines, Siega-Riz and Popkin39).

The CLASS study further included a measure of standing height to the nearest 0·1 cm after students had removed their shoes, and body weight to the nearest 0·1 kg on calibrated digital scales. Overweight was defined using the international BMI cut-off points established for children and adolescents(Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz40). These cut-offs are based on health-related adult definitions of overweight (≥25 kg/m2) but are adjusted to specific age and gender categories for children(Reference Cole, Bellizzi, Flegal and Dietz40).

The average rate of return of questionnaires and consent forms was 51·1 % per school. A total of 5200 students completed the YAQ. Following established criteria for outlying observations in FFQ, we excluded 234 (4·5 %) students reporting average energy intakes <2093 kJ/d (<500 kcal/d) or >20 930 kJ/d (>5000 kcal/d)(Reference Willett41). Listwise exclusion was used for students who did not have complete information on dietary intake, watching television, eating while watching television and height and weight measurements. One of the seven provincial school boards had not allowed measurements of height and weight. The numbers of students on which analyses are based are included in Table 1.

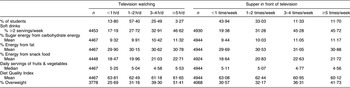

Table 1 Nutrition and body weight in relation to television watching and having supper while television watching among grade 5 students in Nova Scotia, Canada

All percentages and prevalence rates are weighted for non-response (see text).

Statistical analysis

We applied random effects models to examine associations of watching television and of eating while watching television with the nutritional indices and body weights, thereby considering the clustering of students’ observations within schools. We applied multivariable linear or logistic random effects models: logistic models for the binary outcomes of ‘consumption of soft drinks’ and body weights; and linear models for the continuous outcomes of ‘percentage energy intake from sugar out of total energy from carbohydrate’, ‘percentage energy intake from fat’, ‘percentage energy intake from snack food’, ‘daily servings of fruits and vegetables’ and the Diet Quality Index. The number of servings of fruits and vegetables was square-root-transformed to yield a Gaussian distribution. These analyses were adjusted for the confounding influence of child’s gender and household income. All analyses with nutritional outcomes were further adjusted for energy intake as is recommended for analyses of food frequency data(Reference Willett41). To reveal the independent importance of watching television and eating supper while watching television, the multivariable random effects models simultaneously considered ‘watching television’ and ‘eating supper while watching television’. The STATA statistical software package version 9 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses.

As participation rates in residential areas with lower estimates of household income were slightly lower than the average, response weights were calculated to overcome potential non-response bias(Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald22). As all statistical analyses were weighted regarding non-response, the results represent provincial population estimates for grade 5 students in Nova Scotia.

Research ethics

The study was approved by the Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Board of Dalhousie University.

Results

Table 1 presents the nutritional indices by daily hours of television viewed and by weekly number of times supper was eaten in front of the television. The percentage of students consuming two or more servings of soft drinks weekly, the percentage of energy from sugar out of carbohydrate energy, the percentage of energy from dietary fat, the percentage of energy from snack foods and the prevalence of overweight all demonstrated gradual increases with increases in television watching, whereas the Diet Quality Index decreased gradually. Similar gradients were observed for the frequency that children eat supper in front of the television (Table 1).

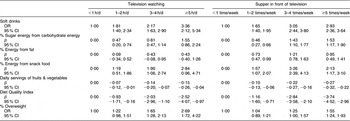

Table 2 shows the associations of television watching and having supper in front of the television adjusted for differences with respect to gender and household income. Television watching showed statistically significant positive associations with consumption of two or more weekly servings of soft drinks, percentage of energy from sugar out of carbohydrate energy, percentage of energy from snack foods, daily servings of fruit and vegetables, Diet Quality Index and percentage of overweight. With respect to frequency of supper in front of the television, all associations with nutritional indices and overweight were statistically significant. The effects of television watching on percentage of energy from fat and on Diet Quality Index were less pronounced than those of supper in front of the television on these nutritional indices (Table 2).

Table 2 Associations of nutrition and body weight with television watching and having supper while television watching among grade 5 students in Nova Scotia, Canada

All estimates are adjusted for child’s gender and household income and are weighted for non-response. Those estimates of nutritional indices are further adjusted for energy intake (see text).

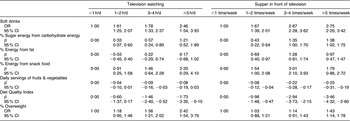

Table 3 presents the independent associations of television watching and eating in front of the television with children’s nutrition and body weights. Relative to the figures presented in Table 2, the independent associations of television watching with nutritional indices seem of a lesser magnitude. The association of eating in front of the television with nutritional indices, in contrast, seems less affected by the consideration of hours of television watching (Tables 2 and 3). Relative to children with the lowest frequency, those with the highest frequency of television watching were 2·42 times more likely to be overweight and those with the higher frequency of eating in front of the television were 1·43 times more likely to be overweight (Table 3).

Table 3 Independent associations of nutrition and body weight with television watching and having supper while television watching among grade 5 students in Nova Scotia, Canada

Estimates for television watching and supper in front of the television are mutually adjusted, as well as adjusted for child’s gender and household income. All estimates are weighted for non-response. Those estimates of nutritional indices are further adjusted for energy intake (see text).

Discussion

The present study shows that eating supper while watching television is negatively associated with diet quality and positively associated with overweight in grade 5 students who are primarily 10 and 11 years old. These associations are independent of the overall time spent watching television.

These results are consistent with past findings on the correlation between television watching and diet quality among children of various age groups. Wiecha et al. showed that increased television viewing was correlated with increased consumption of foods commonly advertised on television, which are generally high in fat and sugar(Reference Wiecha, Peterson, Ludwig, Kim, Sobol and Gortmaker25), while Boynton-Jarrett et al. showed that television watching decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables, which receive little airtime in food advertisements(Reference Boynton-Jarrett, Thomas, Peterson, Wiecha, Sobol and Gortmaker26). Our findings are consistent with these observations as we found that children who watched more television exhibited higher energy intake from fat and sugar, and lower intake of fruits and vegetables. With respect to eating while watching television, Coon et al.(Reference Coon, Goldberg, Rogers and Tucker31) showed an association with poor diets and Marquis et al.(Reference Marquis, Filion and Dagenais32) with an increased consumption of soft drinks and energy-dense foods (including French fries, salty snacks and sweet treats) and a decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables. Our findings are consistent with these observations as well.

As watching television and eating meals while watching television are correlated behaviours, it is important to study the effects of these behaviours on diet quality and body weights simultaneously. However, only few studies have done so. For middle- and high-school students, Feldman et al. reported that eating while watching television was correlated with lower diet quality even after controlling for overall hours of television watching(Reference Feldman, Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer and Story24). Our finding that, relative to the amount of television watching, eating in front of the television is progressively and more strongly associated with poor nutrition suggests that circumstances of eating while watching television have a profound negative effect on the quality of diets. Mechanisms may include effective advertising of unhealthy foods at meal time hours and mindless eating while watching television that results in the consumption of larger portions of unhealthy foods(Reference Colapinto, Fitzgerald, Taper and Veugelers42). Furthermore, children who eat in front of the television will miss out on the nutritional and psychosocial benefits of family meals(Reference Veugelers and Fitzgerald22–Reference Feldman, Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer and Story24).

Dubois et al. showed that 4- to 5-year-old children who frequently ate in front of the television had higher BMI relative to their peers who ate less frequently in front of the television, while they did not observe a significant difference in BMI with respect to overall time spent watching television(Reference Dubois, Farmer, Girard and Peterson20). In contrast, Thomson et al. reported that eating during television viewing was not associated with overweight once overall amount of television viewing was taken into account(Reference Thomson, Spence, Raine and Laing19). We observed that both television watching and eating in front of the television were independently associated with being overweight. Our observations suggest that both sedentary behaviours from television viewing as well as poor nutrition from eating in front of the television contribute to overweight in children. They justify health promotion focusing on reduction of time spent watching television, as well as health promotion activities promoting family meals as a means to avoid eating in front of the television. The American Academy of Pediatrics currently advocates limiting children’s total media time, including television, to less than 2 h/d(43). The current study findings urge that this recommendation is expanded to avoidance of television watching during meals.

The strengths of the present study include the large sample size, population-based design, adjustment for non-response bias and measurements of height and weight, as opposed to self-reported. Although the YAQ and questions on sedentary activities have been validated, responses remain subjective and prone to error. Another limitation is that causality cannot be proved owing to the cross-sectional and observational design.

In conclusion, both television watching and eating in front of the television are independently associated with diet quality and body weight among grade 5 students. Limiting eating in front of the television in addition to overall television time will improve diet quality and reduce overweight in children.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The study was funded by an operating grant of the Canadian Population Health Initiative (principal investigator: P.J.V.), through a Canada Research Chair in Population Health and an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research Scholarship awarded to P.J.V., and through an Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research student award awarded to T.L. Conflict of interest declaration: None to declare. Author contributions: T.L. conceived the study and is the primary writer of the manuscript; S.K. contributed to the study design, conducted the statistical analyses and contributed to the manuscript writing; P.J.V. is the principal investigator of the CLASS study and contributed to the study design, interpretation of the study findings and manuscript writing. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Angela Fitzgerald, MSc, RD, for the coordination of the data collection and processing of the nutrition data; and Jason Liang for data validation and data management.