Obesity is a public health problem worldwide, with a general trend towards an increase in all countries from 2006 to 2016(1). In Latin America, obesity rates are among the highest in the world. In adults, rates vary as low as 19·7 % in Peru to as high as 28·9 % in Mexico, with generally higher rates in females (from 23·4 % in Paraguay to 32·8 % in Mexico) compared with males (from 15·2 % in Peru to 27·3 % in Argentina)(1). In 5–9 years old children, the prevalence rates vary from 8·6 % in Colombia to as high as 21·7 % in Argentina, with higher rates in boys (from 9·8 % in Colombia to 25·6 % in Argentina) than in girls (from 7·4 % in Colombia to 17·8 % in Argentina)(1). In older children (10–19 years), the prevalence rates vary from 6·1 % in Colombia to 14·4 % in Argentina, which higher rates among boys (from 6·3 % in Colombia to 18·3 % in Argentina) than girls (from 6·0 % in Colombia to 11·7 % in Mexico)(1). Concurrently, there are also high rates of undernutrition (such as stunting and wasting) alongside overweight and obesity in Latin America, which is often referred to as the double burden of malnutrition(Reference Jacoby, Tirado and Diaz2).

Several efforts have been designed and implemented in the region to address obesity. Because this is a topic of concern in Latin America, many of these strategies are recent. Also, these have not been systematically reviewed by the level of the strategy, as suggested by the WHO guidelines to help member states prevent obesity(3–5). These guidelines emphasise integrated approaches and intersectoral collaboration to improve diet and increase the level of physical activity(3). The WHO also has the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases(4) and the population-based approaches to prevent childhood obesity(5). Also, Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) developed the Plan of Action for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents(6).

These guidelines specifically emphasise the implementation of strategies from governmental structures to coordinate obesity prevention efforts, to the regulations or laws to support healthy diets and promotion of physical activity level, to the guidelines for the population for following and adopting healthy behaviours and to the level of population-wide or community-based programmes or initiatives. Therefore, this scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the different strategies implemented in Latin America for obesity prevention. Also, this scoping review provides an overview of some of the results found showing the impact of these strategies for addressing obesity in each country.

Methods

This scoping review was part of a broader project on Obesity and Diabetes in Latin America and the Caribbean sponsored by the Global Health Consortium at Florida International University. The national and regional strategies for obesity prevention were divided into four areas, as suggested by WHO guidelines on obesity prevention(3–5):

-

Governmental structures for obesity prevention. This refers to the types of structures in place to support and enhance the obesity prevention strategies, which includes leadership (such as prime ministers, presidents and government ministers), funding dedicated to obesity prevention, monitoring and surveillance systems (such as nutrition surveillance, which has been traditionally defined as a system established to continuously monitor the nutritional status of a population using a variety of data collection methods, a key component to evaluate the effectiveness of the strategies implemented for obesity prevention), workforce capacity (such as skilled staff, training opportunities and quality training) and networks and partnerships (which refers to cross-sectoral governance structures such as non-governmental organisations and private sectors involved in obesity prevention efforts).

-

Regulations to support healthy behaviours. This refers to laws, regulations and policies written at the national level to support healthy behaviours.

-

Guidelines for promoting healthy behaviours. This refers to specific recommendations for individuals to follow to achieve healthy lifestyles.

-

Population-wide or community-based programmes or initiatives. This refers to the specific programmes and initiatives at the local level to directly promote healthy behaviours.

Search strategy

A thorough search of obesity prevention strategies was done using Internet search engines and the country-specific governmental webpages in 2019. We specifically searched for these strategies in seventeen countries in South and Central America, excluding the Caribbean as shown in Table 1. Also, specific keywords were used for searching these strategies by the four sections described above (Table 1). The search was not restricted by year, age groups or gender and we searched for documents in English, Spanish and Portuguese. We also searched for reports from the WHO, the PAHO, FAO, Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama and UNICEF on general obesity prevention in Latin America. Key members of the Health Ministries in each country were contacted to obtain additional information about these strategies (those that responded to our emails are mentioned in the acknowledgement section).

Table 1 Scoping review by keyword/s search by strategy for obesity prevention in Latin America

To identify the impact of these strategies for addressing obesity in the region, we did a literature search in PubMed, Agricola and CINAHL using a similar search as described in Table 1. Because of lack of data, the search was extended to Google and Google Scholar and other reports not published in these databases, such as reports from PAHO. From the identified reports and studies, we also searched for additional references by hand.

Literature selection and data synthesis

We had a team of five research assistants searching for the information, each assigned to two or three countries. The team met with the principal investigator bi-monthly to discuss the search strategy and refined the search terms, as shown in Table 1. A data extraction sheet was prepared, and this was used for all countries included. The search was done in stages; first, the different strategies implemented by each country for obesity prevention were searched; based on the results, the team prepared a preliminary list of strategies identified. Then, based on this list, each assistant searched again for these strategies in their assigned countries to check if that strategy was implemented by that country too. If it had not been implemented, we also searched for news on legislation in the process of approval. Reports with information on several countries were shared among all team members to aid in the search process. The data extraction sheet was housed in a cloud service accessible to all members. The team was bilingual (English and Spanish) and for reports in Portuguese, the principal investigator review them or consulted another person fluent in Portuguese.

Results

National and regional strategies for obesity prevention in Latin America

The strategies implemented at the country level in Latin America are described below.

Governmental structures for obesity prevention in Latin America

The following structures are created to support obesity prevention efforts:

Leadership: Most countries in Latin America define the Ministry of Health as the leading institution/agency for obesity prevention oversight. However, only six countries in the region have established a specific governmental office or committee specifically for obesity prevention efforts (Table 2). Details of the names of each office or committee are found in the online supplementary material.

Table 2 Governmental structures and national plans for obesity prevention in Latin American countries

* Date shown is the last survey conducted. The information was not found for countries with (−). Details of each structure or plan are found in the online supplementary material.

Funding: Specific laws or mechanism to fund these efforts in Latin America was not evidenced in our review.

Monitoring systems: In Latin America, nutrition surveillance has been developed since 1977, but the type of system developed and implemented varies widely by country. A systematic review of official sources in Latin American and Caribbean countries found that twenty-two had at least one nationally representative survey to monitor the nutritional status and among these, sixteen had at least two surveys among children(Reference Galicia, Grajeda and López De Romaña7). Our review found that all countries have a surveillance system in place and the types of surveys used to monitor the nutritional status are shown in Table 2. Details of each survey are found in the online supplementary material. In general, our review found that most surveys were conducted a few years ago. Current data are required to design appropriate interventions and measure their impact.

Workforce capacity: This was not evidenced in our review.

Networks and partnerships: Only a few countries reported this (data not shown); mostly with the Ministry of Education and Agriculture, academia and some non-governmental organisations such as WHO and PAHO.

National plans or policies for obesity prevention

At the country level, a national public health plan with a multi-sectorial and life-course approach will help guide all efforts implemented in each country. Currently, our review found that thirteen countries have obesity prevention plans/policies, and thirteen countries have a general policy to promote healthy dietary behaviours but are not specific to obesity (Table 2). Details with the names of plans or policies are found in the online supplementary material.

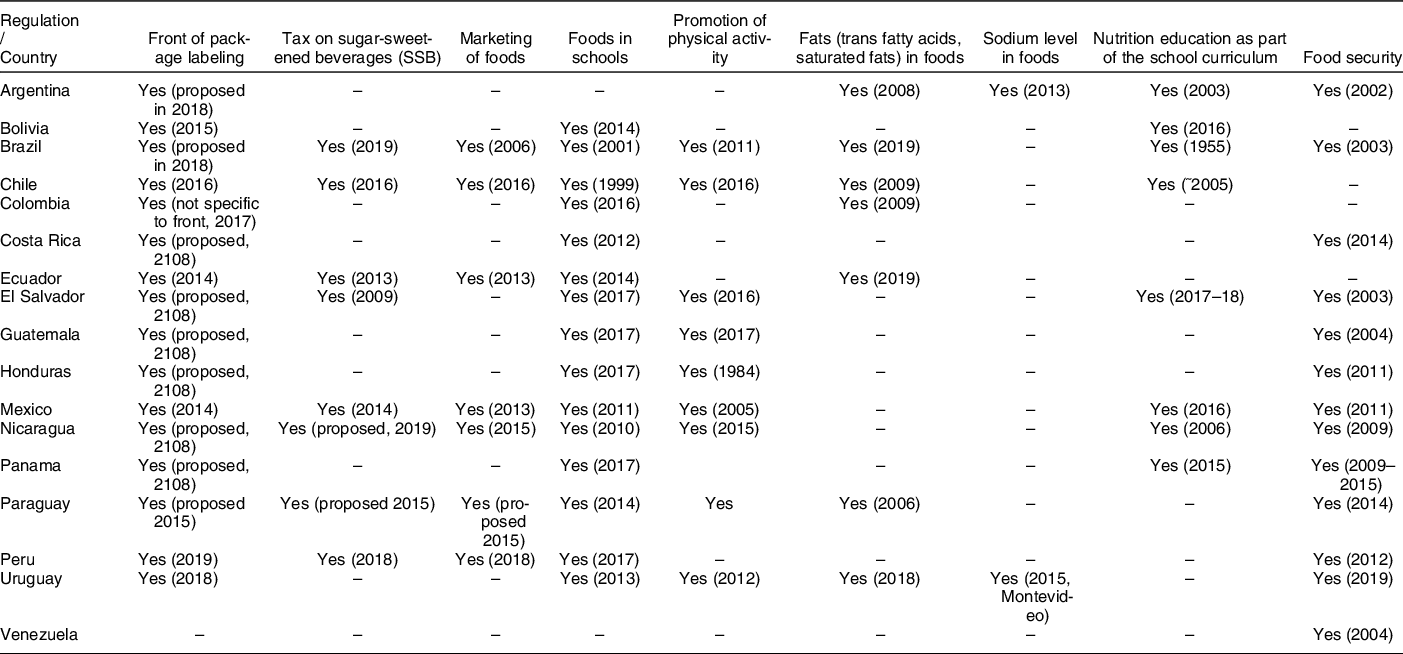

Regulations to support healthy diets

Many countries are planning or have implemented some of the policies and initiatives recommended by PAHO (Table 3). These include front-of-package labelling (nine countries have proposed it and seven countries have implemented it), sugar-sweetened beverage (two countries have proposed it and six countries have implemented it), restrictions on fats (seven countries have in place restrictions on trans-fatty acids and/or saturated fats), restrictions on Na level (two countries) or regulation of the school environment (fifteen countries). In addition, other regulations include regulation for the marketing of foods (one country has proposed it and six countries have implemented such regulation), regulations about nutrition education (nine countries) and about promoting physical activity (nine countries) and regulations about food security (thirteen countries). Details of each regulation are found in the online supplementary material.

Table 3 Regulations implemented or proposed in seventeen Latin American countries to support healthy diets and physical activity

The information was not found for countries with (−). Details of each regulation are found in the online supplementary material.

Guidelines for promoting healthy behaviours

All countries evaluated have local dietary guidelines to translate global dietary guidelines into the cultural, preferences and characteristics of each population (Table 4). Also, nine countries have specific guidelines for children, six countries have guidelines for promoting physical activity and five countries have other healthy behaviours guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of obesity and other chronic diseases (Table 4). Details of each guideline are found in the online supplementary material.

Table 4 Guidelines developed in seventeen Latin American countries to support healthy diets, physical activity and obesity treatment

The information was not found for countries with (−). Details of each programme or initiative are found in the online supplementary material.

Population-wide or community-based programmes or initiatives

Several programmes or initiatives have been implemented in the countries reviewed (Table 5). These include school meal programmes to provide healthy breakfast, lunch and/or snacks to children at schools (seventeen countries), to promote nutrition education (six countries have this at the population level and eleven at the school level), to promote physical activity such as bike routes or Ciclovías (nine countries), to support family agriculture (four countries), to promote healthier environments (three countries have this at the population level and seven at the school level) and to treat obesity (four countries). Details of each programme or initiative are found in the online supplementary material.

Table 5 Population-wide or community-based programmes or initiatives in seventeen Latin American countries to support healthy diets, physical activity and obesity prevention

* At the school or population level. The information was not found for countries with (−). Details of the names of each programme are found in the online supplementary material.

There may be other interventions or strategies not mentioned in this review that were either not published or easily accessible through an online search.

It is important to note that some of the strategies mentioned in this report may be out of date or not being used by the time of this publication, as these may have changed if political changes occurred in the government.

Evidence on the evaluation of the impact of strategies implemented in these countries for obesity prevention

In general, our literature review evidenced a lack of reports and studies evaluating the strategies mentioned in the previous section. We report here the studies/reports found by strategy.

At the level of obesity strategic plans, in 2014, all countries in Latin America signed the Plan of Action for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents(6,8) . This plan adopts a preventive, multi-sectorial and life-course approach and considers the social determinants of health. It aims at promoting an environment that is conducive to healthy eating and a higher physical activity level and making the healthier option the easier option. To support countries in the fight against obesity, PAHO provides technical guidelines and cooperation, advocates for programmes and policies and fosters collaboration among countries. Besides PAHO has other documents to help member states in this effort(9). Also, the Council of Ministries of Health in Central America developed the Plan for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents in 2014–2025(10). In 2015, a meeting in Panama with experts from Healthy Latin America Coalition, PAHO/WHO, the Ministry of Health of Panama, and others discussed the need for a stronger role of the civil society in supporting and promoting policies on food, tobacco, alcohol and level of physical activity in the region(11). In 2016, the Caribbean Public Health Agency and PAHO in collaboration with the Ministries of Health from countries with successful obesity prevention policies, such as Mexico and Chile, developed a roadmap to prevent childhood obesity(12). This is important as lessons learned from efforts that have or have not worked in different countries should be shared. In addition, multi-national studies can provide rich information and insights into how different strategies work with different cultures, ethnic backgrounds, environments, etc. Besides, the Non-Communicable Diseases Alliance developed a Civil Society Action Plan for 2017–2021 on Preventing Childhood Obesity in the Caribbean(13). Lastly, several institutions have convened experts from PAHO, FAO and the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center(Reference Caballero, Vorkoper and Anand14) to evaluate the situation.

At the level of nutritional policies, there are a few successful strategies in terms of acceptance, reach or effectiveness in changing behaviours in Latin America that should be discussed:

Front-of-package label: At the Meeting of Ministers of Health of Central America in 2017, a proposed resolution to establish a front-of-package system for nutritional warnings was endorsed(15). Also, in 2018, the Ministers of Health of MERCOSUR (the Southern Common Market) agreed on a set of principles to promote compulsory front-of-package labelling systems to indicate excessive sugar, Na and/or fat content(16). A study evaluating different labels design for front-of-package labels in 1000 participants from all twelve countries participants of MERCOSUR in 2018 found that the change in labelling significantly improved the ability of individuals to rank products according to their nutritional quality(Reference Egnell, Talati and Hercberg17). Also, a study in Chile done 6 months after the implementation of this regulation found that 67 % of participants selected products with fewer warnings in the label and that the presence of ‘high in’ stamps influenced the purchase decision among 90 %(18). Also, it has been estimated that food companies have modified one of every five products to make it healthier (2015–2016)(Reference Boza, Guerrero and Barreda19). In Ecuador, a study conducted a 1-year post-implementation of this strategy (2015) found that it was widely recognised and understood(Reference Díaz, Veliz and Rivas-Mariño20). In two supermarkets in Quito among seventy-three participants, 88 % reported knowing about this system and 28 % used it, which showed that it significantly influenced their shopping(Reference Teran, Hernandez and Freire21). In Mexico, a survey among parents of children in elementary schools found that 51 % used the displayed nutrient content and reported to prefer the new traffic light system compared with the traditional system(22). In Uruguay, a study found that 95 % of respondents saw the front of package labelling law as positive, regardless of age, gender or socio-economic status(Reference Ares, Aschemann-Witzel and Curutchet23). A greater percentage of individuals from low socio-economic groups (90 %) said the label would help them improve the quality of their diets, compared with those with a medium (86 %) and high (84 %) socio-economic status(Reference Ares, Aschemann-Witzel and Curutchet23). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered medium as there is limited evidence from studies in different countries and most have not included a representative sample of the population.

Sugar-sweetened beverages tax: A recent review focused only on Latin American countries found that at least thirty-nine sugar-sweetened beverage regulatory initiatives have been adapted(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). From these, twenty-eight regulatory initiatives were passed by legislative and executive bodies and eleven are self-regulatory initiatives by the beverage industries. Also, 86 % of regulations by the government are binding; 56 % describe how to monitor and evaluate this, 62 % call for specific sanctions and twenty three specify who the body in charge of this monitoring. In Chile, a sugar-sweetened beverage with more than 6·25 g of sugar per 100 ml is taxed at 18 %, while sugar-sweetened beverage below this threshold is taxed at 10 %. In Ecuador, a tax of USD 0·18/100 g sugar on sugar-sweetened beverages with more than 25 g of sugar per liter. In Mexico, the tax is 1 peso (which is about 0·05 USD) per liter and also an 8 % tax on snacks with more than 275 kcal per 100 g. In Peru, a tax of 50 % is imposed on beverages with more than 6 g per 100 ml. In Brazil, El Salvador and Nicaragua, this is at the proposal stage. In Colombia and Argentina, the strong industry lobbying impeded its implementation. The experience of Mexico and Chile is the most studied so far, as this was implemented a few years ago (2014 in Mexico and 2016 in Chile). In Chile, the results showed that there was a highly significant 22 % decrease in the monthly purchased volume of the higher-taxed, sugary soft drinks(Reference Nakamura, Mirelman and Cuadrado25). The reduction in soft drink purchasing was most evident amongst higher socio-economic groups and higher pretax purchasers of sugary soft drinks. In Mexico, taxed beverages purchases decreased from 200 ml/d at the end of 2013 (just before the implementation of the beverage tax) to about 160 mg/d at the end of 2014 (after about 1 year of the tax implementation), which represents a decline of 12 %(Reference Colchero, Rivera-Dommarco and Popkin26,Reference Colchero, Popkin and Rivera27) . Reductions were higher among the households of low socioeconomic status (17 % decrease by the end of 2014 compared with pretax trends). Also, purchases of untaxed beverages were 4 % (36 ml/capita/d) higher, mainly driven by water. The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered medium as there is limited evidence from studies in different countries and most have not included a representative sample of the population.

Regulation for the marketing of foods: These initiatives have varied widely by country, with some having formulated guidance, while other restrictions, with some sanctions, but most do not have a clear description of their monitoring. Banning unhealthy food advertising may have a positive impact on children’s diets. A review in Brazil showed that most studies were based on law analysis or qualitative study of advertisement, and several companies had differences in ethical behaviour regarding food advertisements, showing a lack of commitment to the policies on food advertisements(Reference Kassahara and Sarti28). So far, Chile is the country that has implemented the most comprehensive regulation of food publicity, regulating 35–45 % of processed foods and beverages high in added sugar, Na or saturated fat. Also, there is a ban on the marketing of certain unhealthy foods during selected child TV programmes. In Mexico, the regulation prohibits advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages to children mainly in TV or movie theatres, with some exceptions for certain programmes. Brazil limits all publicity targeting food for children. Bolivia, Chile and Mexico also require to include messages to promote healthy lifestyles, and Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru require the inclusion of warning messages about the potential health effects of certain products(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). Ecuador and Nicaragua are at the proposal stage to implement it, while in Argentina, it was vetoed by the President(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). In Mexico, an analysis of children’s advertisements in 2012–2013 in the most popular public TV showed that about 75 % of the total food and beverage advertisements were aimed directly or indirectly at children(Reference Théodore, Tolentino-Mayo and Hernández-Zenil29). Even among companies that had signed the self-regulation, more than 31 % of the advertising of unhealthy products were aimed at children or adolescents. A review of twenty-three studies (six in Chile, five in Mexico, four in Brazil, three among Hispanics in the USA and one in Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Honduras and Venezuela) about food advertising directed to children on TV found a high exposure of TV food advertised for children and their family, which has been associated with preference and purchase of unhealthy foods and with overweight and obesity(Reference Bacardí-Gascón and Jiménez-Cruz30). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is also considered medium.

School meal programmes: Only a few studies are evaluating the effectiveness of school-based programmes. For example, in Brazil, a study of twenty-one public schools in one region in 2014 found that about 31 % of children were overweight, that breakfast and snacks were composed of 68 % of ultra-processed foods, while 92 % of the lunch foods were unprocessed and minimally processed foods(Reference Batista, Mondini and Jaime31). In Colombia, children participating in the programme may have better school performance(Reference Niny32). In Chile, this programme has been shown to reduce school drop-out rates(Reference Villena33). In Mexico, the regional programme ‘Health to Learn (Salud para Aprender)’ found a decrease in overweight and obesity from 25 % in 2010–2011 to 19 % in 2016–2017 among preschoolers, from 32 % to 30 % in elementary children and from 38 % to 34 % in adolescents(Reference Trejo Hérnandez and Raya Giorguli34). They also found that the % of breakfast consumption increased from 84 % in 2010–2011 to 86 % in 2016–2017, consumption of fruits and vegetables 3–4 times per week increased from 34 % to 36 % and sedentarism improved by 1–2 points. In Peru, the Milk Glass Program, which impacted 61 % of children 0–6 years and 18 % of children 7–13 years, found that 63 % of those participating had a decreased risk of obesity(Reference Diez-Canseco and Saavedra-Garcia35). A systematic review of twenty-one studies (n 12 092) with different types of educational interventions in children (nutritional campaigns, physical activity level and environmental changes) in Latin America found that mixed approaches combining nutritional campaigns, physical activity level promotion and environmental changes were the most effective interventions(Reference Mancipe Navarrete, Garcia Villamil and Correa Bautista36). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is also considered medium.

Regulation of the school environment: Changing the food environments can have a strong influence on the school-age population and could lead to changes in food preferences and weight status. These policies have been implemented in several countries as described previously, but they differed in their legislation and how strict they are. For example, in Brazil, Ecuador, Chile, Peru and Uruguay, the policies to limit sugar-sweetened beverages in schools are through their legislative and executive, while in Costa Rica and Mexico, this has been through executive decrees only, which may have a different impact(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). Although all are mandatory, some have not specific sanctions if schools are not in compliance, such as in Ecuador. Also, some countries are very strict in the type of beverages banned. For example, in Peru, drinks with more than 2·5 g of sugar per 100 ml are not allowed, while in Ecuador and Uruguay, the limit is on beverages with more than 7·5 g of sugar per 100 ml and in Mexico almost all beverages that provide calories are banned, except on Fridays(Reference Bergallo, Castagnari and Fernández24). Therefore, most legislations allow 100 % fruit juices, which can still add to the total calories consumed per day, except for Mexico. Also, this legislation is mostly for public schools and at the elementary level. Although there are no results available yet on their impact on reducing obesity, there are a few obstacles encountered in their implementation. For example, in Mexico, the food industry has shown strong opposition, which delayed the process(Reference Charvel, Cobo and Hernández-Ávila37). Also, studies in Mexico found that the schools lacked the space, food safety measures or the structure to implement these policies(Reference Gallegos Gallegos, Barragan Lizama and Hurtado Barba38). They also lacked a strong strategy to implement this throughout and faced difficulty in changing culturally strong practices, among others(Reference Treviño Ronzón and Sánchez Pacheco39). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered weak as there are very limited studies.

Programmes to promote physical activity: These include the modification of the school curriculum to increase physical activity level, policies in urban planning to increase access to sidewalks and areas of recreation and physical activity, among others. A global review of the impact of such policies on obesity found that individuals living in walkable communities, with access to parks and other recreational areas, with sports facilities or spaces for recreation in schools and greater access to stairs, were all associated with higher levels of physical activity(Reference Sallis and Glanz40). In Latin America, only a few studies are evaluating such programmes. In Colombia, surveys conducted in 2009 found that individuals participating in the bike route (Ciclovía) programme met the physical activity recommendation in leisure time (60 %), and most participants met it by cycling for transportation (71 %)(Reference Torres, Sarmiento and Stauber41). Another survey among current and former programme coordinators of sixty-seven bike routes in 2014–2015 found that the average number of participants per event was > 40 000 (40–1 500 000) with an average length of 9·1 km (1–113·6)(Reference Sarmiento, Díaz del Castillo and Triana42). The participation of minority populations was high (61·2 %). The current study also evaluated the sustainability and scaling-up of five programmes and they all met the most important factors for this, such as some level of government support, alliances, community appropriation, champions, organisational capacity, flexibility, perceived benefits and funding stability. However, there were several differences in their design, operations, political affiliations, funding and alliances, which may be important for the diversity and inclusion of different segments of the population. The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is considered weak as there are very limited studies.

Efforts to reduce fat or Na in foods: In Argentina, a law was enacted in 2013 to regulate the maximum Na levels in meat products, farinaceous foods and soups, bouillons, and dressings. If all these foods fully comply with this regulation, this would reduce Na intake by about 30 mg/d (Reference Elorriaga, Gutierrez and Romero43). In a study conducted in 2019, more than 90 % of the food products included in the national Na reduction law in Argentina were found to be compliant(Reference Allemandi, Tiscornia and Guarnieri44). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is also considered weak.

Programmes to promote nutrition education: In Chile, the 5-A-Day campaign was tested on an adult sample (n 1897), finding after 1 year that recalls of the materials was high and that the proportion of people saying that they consumed 3–4 servings a day increased from 49 % to 51 %(Reference Vio, Albala and Kain45). Another study in Chile found that 9 months after the implementation of the Santiago Sano programme found that 22 % of the participants had improved their nutritional status(46). The evidence on the effectiveness of this strategy is also considered weak.

Discussion

Our results found that most countries defined the Ministry of Health as the lead institution for the oversight of obesity prevention strategies. Although all countries have implemented a survey to monitor obesity, most surveys were done several years ago, with only a few countries with recent surveys. Most countries reviewed (thirteen out of seventeen countries) have a national obesity prevention plan with published guidelines for following healthy diets. Also, eight countries have guidelines for increasing the level of physical activity and other healthy behaviours. The most common regulations implemented/designed related to obesity prevention are front-of-package labelling (sixteen countries), nutrition education in schools (nine countries) and school environment (fifteen countries). The most common community-based programmes related to obesity prevention are school meals (seventeen countries), nutrition education (fourteen countries) and complementary nutrition (eleven countries).

This scoping review also provided an overview of the evaluation of these strategies. Although only a few have been evaluated, some had positive results. In particular, those with positive results are the strategies that have a coordinated, multi-disciplinary and multi-sector approach considering aspects of behavioural change for improving diet and level of physical activity that involves parents and other community members. Obesity prevention efforts should have multidisciplinary approaches involving several sectors; therefore, their evaluation requires expertise in designing and evaluating complex interventions. These should include promoting diet and physical activity level integrated with the different environments and should evaluate how the multiple influences on behaviours and obesity operate differently in subgroups. However, many universities and research institutions in Latin America have limitations for providing the training, resources and infrastructure(Reference Yavich and Báscolo47) necessary for these types of studies. Besides, funding for research is very limited and often rely on external funding and donors. Also, it is important to evaluate if interventions in the healthcare system are a good approach for those that regularly have no access to this; these individuals may need another type of intervention. Also, these efforts must be regulated, with legislation and executive-level support, which is key for their continuation in time. Examples of some of the strategies that have shown positive results include front-of-package labelling, school environment/meal regulations/programmes, food marketing regulation, beverage tax and programmes to improve the level of physical activity.

An important gap identified in this scoping is the lack of baseline data. This is key when evaluating the impact of the different strategies implemented in each country. As shown in Table 2, many countries do not implement regular surveys to monitor obesity. Furthermore, some of the strategies found seem to overlap with other programmes, and it was not clear from our search if all programmes described here were being implemented or were active. Some may have been discontinued without an evaluation process, or maybe they were evaluated but the results were not published. In some countries, the discontinuation may be due to a change of government, particularly those without legislation. Also, although some programmes seem to be active, some may not be receiving funds from the government; therefore, they may not be implemented as intended.

Many of the strategies described in this review are aimed at reducing food insecurity as undernutrition has been traditionally more prevalent in Latin America. The dual burden of malnutrition(Reference Jacoby, Tirado and Diaz2), in which undernutrition coexist with obesity, poses a major challenge in Latin America. The WHO proposed the double-duty actions to address this(48). Double-duty actions include interventions, programmes and policies that can be implemented to simultaneously reduce the risk or burden of both undernutrition and obesity. These could include programmes or strategies to protect and promote exclusive breast-feeding, to optimise early nutrition and maternal nutrition, school food policies and marketing regulations, such as the ones discussed in this review.

The strategies described here require many resources and skills that are lacking in Latin America. Also, the economic growth in the region in the past two decades has led to major socio-economic disparities, which may account for a large variation in the obesity increase among women, particularly in Mexico(Reference Su, Esqueda and Li49). This economic growth has vastly changed the foods available in the region, with a sharp increase in high-energy processed foods, replacing the traditional foods consumed in most of these countries. This was evidenced in a sales analysis of ultra-processed products from different outlets in thirteen Latin American countries in 2000–2013(50), which was associated with obesity. It also showed that processed foods sales steadily increased in most countries, particularly in urbanised areas and those opened to foreign investment and deregulated markets. This combination of factors has led to an environment that is not conducive to healthy behaviours.

On the other hand, in Latin America, the engagement of different health professions and public institutions with multi-disciplinary settings is a strength when implementing obesity prevention measures. The food industry is yet to be engaged in these efforts, with only a few initiatives. Their low engagement could be related to the change of governments and rules and also possibly lack of ethical principles guiding public–private partnerships. With the increased sales of processed foods in urbanised areas in Latin America, they must get involved. Other sectors such as communications, economics and policy analysis should also be included. This is key as a multisector collaboration (government–academic–civil society–food industry) is critical in identifying and conducting research and translating this evidence into programme and practice. This type of partnership, with well-defined and measurable goals and established ethical principles guiding their actions, will lead to more effective interventions. It will also help the governments be better informed of the efforts that are most effective based on research and the limitations and improvements that must be implemented.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this scoping review is that it followed a systematic process to identify the different strategies implemented in Latin America. The search strategy was comprehensive, with the inclusion of reports and publications in Spanish, English and Portuguese. Therefore, we believe that we captured the relevant information from all the different sources searched. A potential weakness of this scoping review was that some strategies may not have been published or the ones found may have not been updated with the changes in government. Also, there were limited studies or reports found evaluating the impact of these strategies; also, some reports may have not been published yet as some of these strategies are very recent to have impact results. Besides, some countries may not have experts to translate these results into a publishable peer-reviewed manuscript. Some reports could also be classified or not released to the public. Furthermore, the few studies with results on the impact of the identified strategies used different study designs, which was challenging when synthesising the results. Some studies included results about the number of individuals impacted, while others showed results on the improvement in dietary patterns and level of physical activity. Most included only a relatively small number of individuals, which limits the generalisability. Only one or two studies evaluated the long-term impact on obesity.

Conclusion

The Latin American countries included in this review have been designing and implementing important public health programmes for obesity prevention, such as front-of-package labels, regulations and programmes for the school environment and to provide healthy meals, food marketing regulations, sugar-sweetened beverages tax and to promote the level of physical activity. However, there is a need to evaluate programmes and initiatives, by gathering baseline data before these are implemented at the population level and evaluating their impact after implementation. Also, there is a need to implement and continue successful combined programmes and policies that tackle both undernutrition and overweight. This information can help assess the actions that can be generalised to other countries within the region and can help inform how to prevent obesity in different settings.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the following key members of the Health Ministries in the different countries for sending additional information about the programmes they currently have active: Lic. Alicia Mombru from the Ministry of Health in Argentina; Carolina Suárez Vargas and Ligia AydeeVanegas Marquez from the Ministry of Health in Colombia and Dra. Flavia Fontes from the Ministry of Health of Panama. The authors also thank Carolina Velasco, Nicholas Gonzalez, Jessica Alfonso, Katherine Alonso and Lisett Castellanos from the Department of Dietetics and Nutrition, Stempel School of Public Health, at Florida International University for their contribution to the search for the data presented in the tables. Financial support: This scoping review received funding from the Global Health Consortium, Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work, Florida International University, Project ID # 2500191. Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: All authors have been involved in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and for approving the published version. CP is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001403