INTRODUCTION

In 1519, the high-ranking politician, officer, and leading humanist of Fribourg, Peter Falck (1468–1519), announced to his fellow humanist Joachim Vadian (1484–1551) that he was about to leave for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.Footnote 1 This was not the first time Falck left for the Holy Land. Like the more famous fifteenth-century pilgrims William Wey (1405/06–1476) and Felix Fabri (ca. 1440–1502), he felt the urge to visit the site of the Passion for a second time. He had first visited only four years before, and his leadership en route had been praised to their mutual friend Desiderius Erasmus (ca. 1467–1536) by the English humanist John Watson (d. 1537).Footnote 2 Ironically, Erasmus may at the time have been busy composing the colloquy Peregrinatio Religionis Ergo (Pilgrimage for religion's sake, 1526), a fierce attack on the very idea of Christian pilgrimage.Footnote 3 Falck told Vadian in his letter that he not only planned to go to Jerusalem for a second time but also planned to see the Iberian Peninsula afterward: “I am drawn by desire to see places as it keeps me from sitting around at home and becoming as big and fat as when you saw me for the first time.”Footnote 4 Falck effortlessly combined describing pilgrimage as a workout program with the endowment of a chapel in St. Nicholas, the main church of Fribourg, dedicated to the Passion.Footnote 5 The chapel was intended as his burial place but never served its purpose. Falck fell victim to the Plague on board the ship, and did not make it home from his second voyage to Jerusalem. His compatriots made sure that his corpse was not thrown into the sea, as were those of other victims, and managed to secure him a Christian burial in Rhodes.Footnote 6

It is tempting to see Falck's death near Rhodes—immortalized in the giant Dance of Death painted by Niklaus Manuel (ca. 1484–1530) in Bern around 1520 (fig. 1)—as a symbol of the end of an era—namely, the era of medieval pilgrimage.Footnote 7 One should not, we argue, give in to that temptation. Rather, Falck's pilgrimage of 1519 testifies to the robustness of pilgrimage to Jerusalem as a practice despite the vicissitudes of the time. Notwithstanding the humanist critique of pilgrimage and the conquest of the Holy Land by the Ottomans just two years before, pilgrimage to Jerusalem continued.

Figure 1. Peter Falck surprised by death. Detail from Niklaus Manuel's danse macabre, ca. 1517–22, copy in gouache by Albrecht Kauw, 1649. Bernisches Historisches Museum, Bern, Inv. 822.1-24. Photography by Christine Moor.

A growing body of scholarship in the past two decades has effectively challenged the narrative of the decline of pilgrimage to Jerusalem and established its resilience in the period. This article aims to take the discussion forward. We propose here a broader framework of analysis and paint a richer image of early modern pilgrimage, which, as the following discussion will show, was not only a robust religious tradition but also part of the fabric of early modern life—intellectually, culturally, and socially. As such, it was a vibrant and often contested field. Let us continue with Falck a little longer.

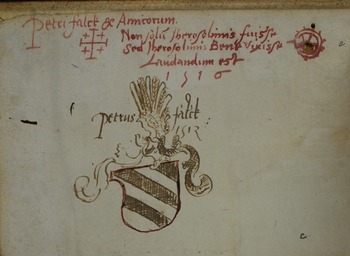

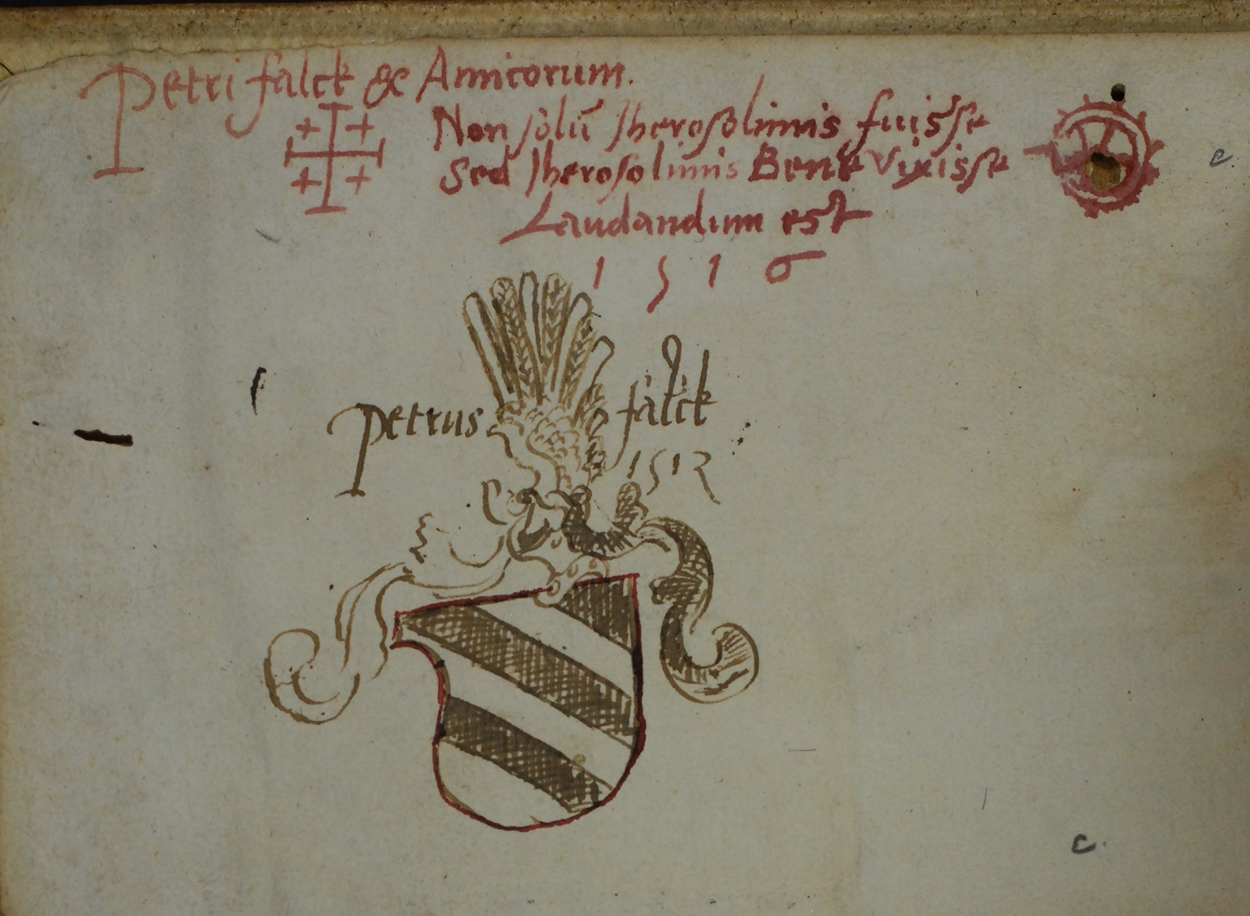

As an early sixteenth-century pilgrim, Falck unites different stances and practices that he shares both with his late medieval predecessors and his early modern successors. From his first pilgrimage to the Holy Land Falck had brought back a medallion made of the earth of different holy places, only to bestow it on a friend in a typical act of Renaissance numismatic gift exchange.Footnote 8 His pilgrimage was connected to a literary tradition, and, in the course of it, one encounters Falck reading and annotating other pilgrimage accounts, buying books in Venice, notetaking on site, writing letters en route, and being mentioned in letters and pilgrimage accounts by others. As other contemporaries, Falck referred to his pilgrimage on the first pages of books he owned.Footnote 9 As part of the ex libris (fig. 2) of his copy of Erasmus's Adagia (Proverbs and sayings, 1510 edition)—adorned with his coat of arms, the Jerusalem cross, and the wheel of Saint Catherine, the typical emblems of the pilgrimage to the Holy Land—Falck quoted Jerome's famously critical dictum on pilgrimage but subtly changed its meaning by adding the word only: “What is praiseworthy is not only to have been to Jerusalem, but to have lived well in Jerusalem.”Footnote 10 Criticism of pilgrimage was in itself part of the pilgrimage complex and pilgrim writers referring to the church fathers’ criticism were not so much sounding the death knell of pilgrimage as playing on a time-honored topos of that literary tradition.Footnote 11 This ingrained, traditional criticism is often misinterpreted in modern scholarship.

Figure 2. Ex libris in Peter Falck's copy of Erasmus's Adagia (Strasbourg: Schürer, 1510). Zentralbibliothek Solothurn, Rar 332. Image courtesy of Zentralbibliothek Solothurn.

Falck's candid confession of his desire (voluptas) to see new places contradicts the cliché of pilgrims as single-mindedly fixing on their destination.Footnote 12 In the context of early modern historiography on travel, such a plurality is still often seen as deviant and aberrant of actual pilgrimage. Foundational and still-definitive studies on early modern travel and ethnography have differentiated between their protagonists and the supposedly pious pilgrim of old, taking it as given that an interest in human variety is in itself an aberration of pilgrimage and an indicator of an author's secular orientation.Footnote 13 The claimed linearity of destination-oriented pilgrimage is contrasted with the circular perambulations of the traveler.Footnote 14 The ideal of the early modern traveler who has discarded the blinkers of piety and pilgrimage is manifest, we are told, in the figure of Odysseus, who stands for “an insatiable inward hunger for knowledge and new experiences, which lead him to impiously abandon his family and country of origin and to break the boundaries of fixed divine order.”Footnote 15 However, from late antiquity up to the Renaissance, Odysseus in some contexts also symbolized perseverance in temptation and orthodoxy in the face of heresy.Footnote 16 Early modern authors, therefore, had no qualms in presenting their pilgrimages—which included their fair share of island hopping, shipwreck, pestilence, and piracy—in Homeric terms, effortlessly juxtaposing references to pious Helena (ca. 250–ca. 330), the mother of Constantine, with references to the eponymous Spartan beauty queen.Footnote 17

Falck's case shows how piety, erudition, and a self-deprecating irony could bleed into each other in and around the field of pilgrimage. To this plethora of motives and interests, let's also add social climbing. In Fribourg and nearby Bern, two of Falck's political and mortal enemies were both known to be worthy Knights of the Holy Sepulcher. Falck had had a leading role in the mock trial that ended with the execution of one of them, so he may well have been moved to travel by peer pressure—or, some surmise, as penance for that very murder. As the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were rich in aspiring would-be nobility, a fair share of pilgrims may have had the social environment at home on their minds while they were traveling to the Holy City. This did not disenfranchise them from being pilgrims. As we will show in more detail below, honor, career, and piety are hard to distinguish in a religious society.Footnote 18

Following Falck's case as a baseline, the following pages present a series of case studies that individually explore different modes or types of early modern pilgrimage, both en route and back at home. In showing the varieties of the phenomenon we are at the same time keen on highlighting the genealogical threads that link it to the longer tradition of pilgrimage to Jerusalem. We have no essentialist notion of pilgrimage. Within this more flexible framework, both those who arrive in Jerusalem for the sake of piety and those who seek salvation are pilgrims. Even those who identify only temporarily or ironically as pilgrims form part of the phenomenon. In the Latin or European tradition we study here, we define as Jerusalem pilgrimage any journey that involved the visiting of holy places in the Holy Land and the full or partial identification of a traveler with the established post-Crusader tradition of pilgrimage. Such identification could happen by use of the Franciscan Custody's infrastructure or by the appropriation of symbols and titles that clearly relate to that tradition. The new evidence presented in the following short case studies suggests that there is a need to ask in what ways the Jerusalem pilgrimage was enmeshed within early modern culture.

Protestant pilgrimage has haunted scholarship on early modern religion and culture for some time. As is usually the case with specters, however, its appearances have been elusive, while the evidence for its existence is scattered. We gather and analyze a set of both Protestant and Catholic cases and emphasize pilgrimage as a shared field, in which cross-confessional elements were continually present. In recent years a series of scholars have begun to pay sustained attention to early modern or post-Reformation pilgrimage and to pilgrimage to Jerusalem in particular. Historian Folker Reichert has recently collected and analyzed a number of Protestant Jerusalem pilgrimage accounts, although still trying in part to accommodate his findings with the decline narrative.Footnote 19 Paris O'Donnell, Sean Clark, and Mordechay Lewy have interpreted pilgrimage (or anti-pilgrimage) as a genuine expression of Protestant piety and a means of sharpening one's confessional identity or as a medieval hangover that continued for some time even though its religious foundation was waning.Footnote 20 Simon Mills demonstrated the liveliness throughout the seventeenth century of Anglican pilgrimage to Jerusalem and other Levantine biblical sites.Footnote 21 Literary historians and bibliographers mapped the early modern body of pilgrimage writings.Footnote 22

Zur Shalev, Beatrice Groves, Adam Beaver, and Thomas Noonan have pointed to the prominence of Holy Land studies and travels within early modern scholarship (both Catholic and Protestant) in such innovative disciplines as antiquarianism, cosmography, philology, and theology.Footnote 23 For Catholicism, Marianne Ritsema van Eck recently studied the early modern Franciscan control of Holy Land literature and practices, highlighting their active engagement with both intra- and interconfessional polemics.Footnote 24 The study of European fifteenth- and sixteenth-century pilgrimage has also grown to include Jewish travelers and pilgrims. Martin Jacobs and David Malkiel, for example, have placed this tradition in the context of Orientalism and humanistic culture.Footnote 25

This body of scholarship redistributes the burden of proof. The narrative of the decline of pilgrimage to Jerusalem looks less and less convincing the more one looks for (and finds) sixteenth- and seventeenth-century pilgrims. Due to the nature of available sources, the narrative of decline never rested on extensive and solid long-term statistical analysis in the first place. It resulted from methodological errors, such as a fixation on Venice and Venetian pilgrim galleys, a priori assumptions about post-Reformation religious practices, and the categorical mistake of reading anti-pilgrimage polemics and Catholic complaints about the absence of pilgrims as statements of facts about actual pilgrimage.Footnote 26 As soon as one allows for the possibility that pilgrimage to Jerusalem may have flourished in some form beyond the Reformation, evidence happens to appear in the most diverse places. To acknowledge and appreciate the evidence one needs to understand early modern pilgrimage as a cultural field. This field encompassed a variety of beliefs, practices, genres, and objects. In order to comprehend it, one needs to study different kinds of sources—such as family archives, books, heraldry, seals, maps, paintings, relics, tapestries, and coins—and different kinds of activities, such as real and mental travel, piety, and scholarly methods and criticism. Consequently, one needs to combine different historiographies, such as intellectual history, archival studies, history of religion, and the history of the book. Understood both as travel and cultural representation, post-Reformation pilgrimage to Jerusalem is palpable if one is willing to collect and consider the varied, scattered, and hitherto neglected evidence.

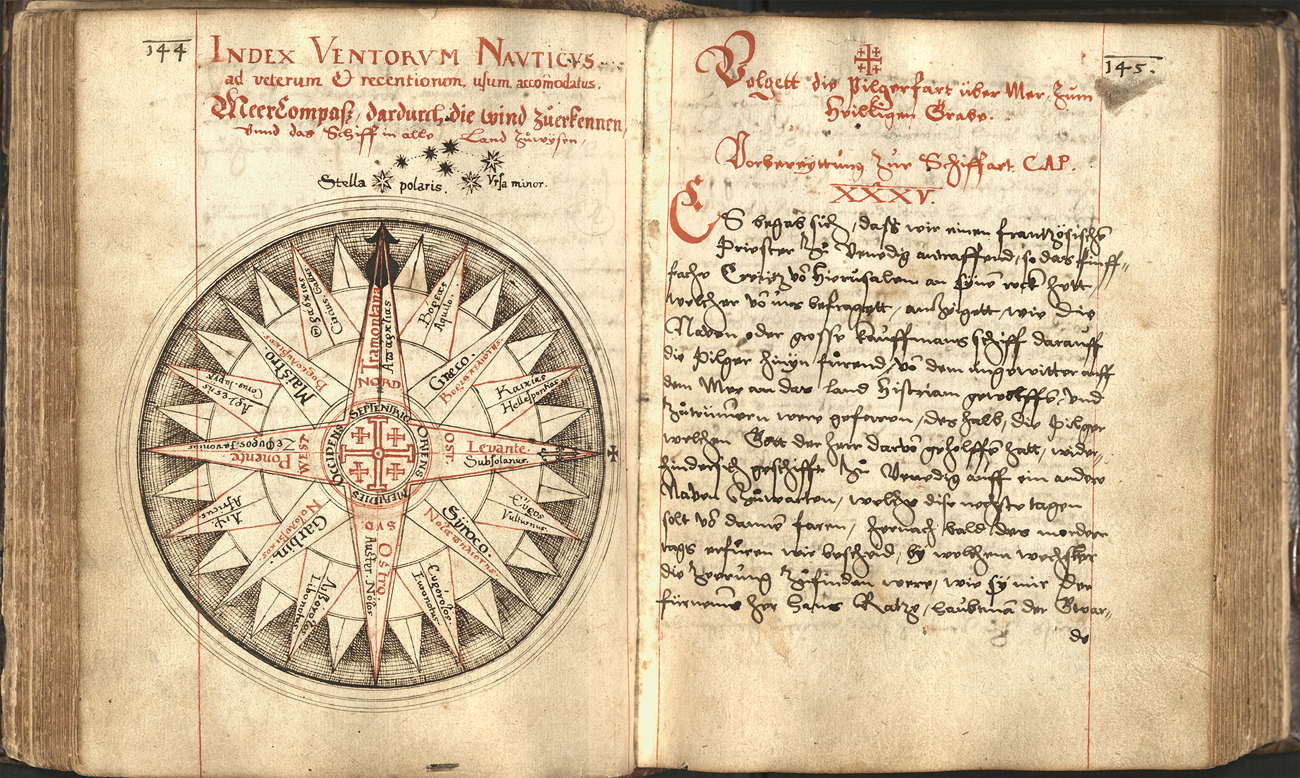

ODYSSEUS IN JERUSALEM: PILGRIMAGE ACCOUNTS AS A MEDITERRANEAN GENRE

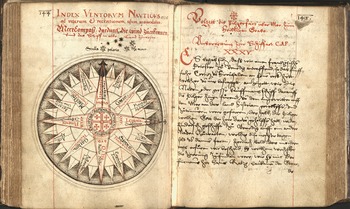

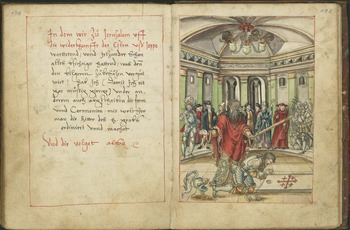

Falck and other early modern pilgrim-authors were clearly committed to religious beliefs, practices, and polemics, which are amply documented in their written accounts. The Jerusalem journey, however, was in many respects a Mediterranean phenomenon. In fact, pilgrim writers often referred to pilgrimage to Jerusalem as Meerfahrt (sea voyage) and sometimes to their pilgrimage account as Meerbuch (sea book).Footnote 27 Some pilgrims, such as the Graubünden priest Jakob Bundi (1565–1614), even considered the sea voyage indispensable for a genuinely religious experience: Bundi's account of his 1591 pilgrimage to Jerusalem is adorned with the motto “If you don't travel by sea, you don't know how to pray to God” (“Chi non va per mare Iddio non sa pregare”).Footnote 28 The Fribourg canon Sebastian Werro (1555–1614), who traveled to the Holy Land a decade before Bundi, had his pilgrimage account furnished with a new title page when the party sets sail in Venice, many pages into the codex, as if to say that the actual pilgrimage only began at sea (fig. 3).Footnote 29

Figure 3. The beginning of the sea voyage in Sebastian Werro's pilgrimage account. Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire, Fribourg, MS E 139, 144–45. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire.

The narratives produced by the Jerusalem pilgrims were rooted in the experiences they accumulated along the route. Themes such as the sea and life on board ship, classical antiquities, encounter with Islam, Eastern Christianity, and Judaism, flora and fauna, are all very common in early modern pilgrim accounts. Mediterranean shores and waters were also pilgrim burial sites, as in Falck's case. Falck's by now vanished tomb and the sumptuous tomb of his fellow traveler Melchior zur Gilgen (1474–1519) became lieux de mémoire for compatriots visiting Rhodes.Footnote 30 The Swiss pilgrims of 1519 paid a visit to the tomb of their compatriot Hans von Meggen (d. 1497), who had died fighting off pirates as a pilgrim to Jerusalem and was buried in Crete. Jost (Jodocus) von Meggen (1509–59) too remembered his fallen uncle when coming through Crete in 1542.Footnote 31 There are also testimonies on other pilgrims buried somewhere in the eastern Mediterranean, such as the tomb of the acclaimed physician—and recent pilgrim to Jerusalem—Andreas Vesalius (1514–64) on Zakynthos, just beside the supposed tomb of Cicero.Footnote 32 The Mediterranean was in itself a sacred landscape that was navigated by seamen and passengers with the aid of shrines en route.Footnote 33 And had not the apostle Paul himself been storm tossed, shipwrecked, and stranded on foreign shores? Jerusalem pilgrimage literature can therefore be understood, as we argue below, as a Mediterranean genre, not at all at odds with the perambulatory periplus.

An early example of the familial connection of pilgrimage literature to Mediterranean writing is Petrarch's (1304–74) imaginary journey to the Holy Sepulcher (late 1350s).Footnote 34 Petrarch embarks, as it were, in Genoa and recounts classical sites and texts as he moves along coasts and between islands eastward to Jerusalem. It is true that the Mediterranean as entity and medium was already present in several medieval pilgrimage narratives. Saint Willibald (ca. 700–ca. 787), in the eighth century, Saewulf (traveled 1102–03), in the early twelfth, and others narrated their sea journeys in varying degrees of detail.Footnote 35 Contemporaries of Petrarch, such as Ludolf von Suchem (traveled 1336–41) and Niccolò da Poggibonsi (traveled 1345–50), devoted more elaborate sections of their narratives to the sea, its perils, and some islands.Footnote 36

However, during the fifteenth century, writing the Jerusalem journey became more meaningfully linked to humanist-antiquarian genres that had already begun to develop in the late fourteenth century, such as world histories, cosmographies, ethnographies, atlases, and various forms of travel accounts. Isolarii, proto-atlases of islands, such as Cristoforo Buondelmonti's (1386–ca. 1430) Liber Insularum Archipelagi (A description of the islands of the archipelago, ca. 1420), provided richly illustrated historical and geographic descriptions of Mediterranean landscapes.Footnote 37 Bernhard von Breydenbach's Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam (Pilgrimage to the Holy Land, 1486), the voluminous and influential account by the canon of Mainz, also demonstrates these hybrid qualities. Breydenbach and those he had employed in the publication process produced a book based on a diverse range of literary sources, firsthand accounts, and visual representations, which cover themes and regions well beyond the Holy Land—distances, islands, animals, and more. In the late sixteenth century, Giuseppe Rosaccio's Viaggio (1598), a small, printed album of annotated Mediterranean views aimed at wider audiences, continued and merged these traditions.Footnote 38

These literary methodologies and conventions for the description of landscape—measuring monuments, collecting inscriptions, suggesting etymologies, producing city views, noting local customs—were shared by all educated European pilgrims, regardless of their confessional affiliation. In this sense, we argue, Catholic and Protestant pilgrims produced strikingly similar narratives, which in turn were akin to contemporary nonreligious Mediterranean narratives. All were shaped by common cultural backgrounds and literary conventions. To illustrate this point further, let us briefly compare the structure and scope of two well-known and related accounts, published around the year 1600: the most devout Catholic journey of Jean Zuallart (1541–1634) and the Levantine grand tour of the Anglican humanist George Sandys (1578–1644).Footnote 39

Zuallart, who had traveled to the Holy Land in 1586, authored one of the most influential pilgrim accounts written in the sixteenth century, Il devotissimo viaggio di Gerusalemme (Most devout voyage to Jerusalem, 1587), which appeared later in several expanded editions and translations. As one may expect, Zuallart's work was focused on pilgrimage—its history, its justification, with a good dose of polemic against Protestants. The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, Zuallart wrote, was revered not only by all Christians, but also by Muslim enemies of the cross, “and only our heretics with their master Satan hate it, would not dare enter, and would have destroyed it if it were in their power.”Footnote 40 Zuallart also elaborated on the best ways to prepare for the journey (bring some soap; beware of fruits).Footnote 41

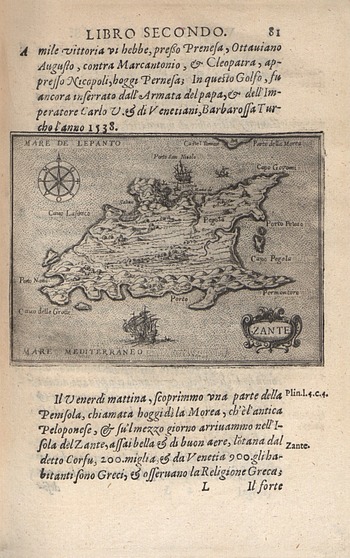

The descriptions of Jerusalem and other sacred sites are expansive and detailed. However, following his predecessors, Zuallart devotes the whole of his second and fifth books to a description of the route from Venice to Jaffa and back—roughly a third of the text in the first edition. The authorities he quotes are often Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and Pomponius Mela, all of whom he uses to identify Homeric, Virgilian, and other classical sites.Footnote 42 The day-to-day life of the Mediterranean also captures Zuallart's attention. Tripoli receives a lengthy description—its history, weather, monuments, population, products, and Turkish administration.Footnote 43 At the end of the expanded 1608 French edition, he included a detailed description of the political structure of the Venetian government.Footnote 44 Zuallart filled his book with many illustrations, engraved by Natale Bonifazio (1538–92), a respected Dalmatian artist (fig. 4). These included first and foremost maps and plans of the sacred sites, most likely provided by the Franciscans in Jerusalem;Footnote 45 views depicting landscapes and monuments in and around Jerusalem, which Zuallart had sketched himself; as well as maps of Italy, Venice, Crete, the eastern Mediterranean, among others, which Zuallart had probably obtained in Venice or Rome. Zuallart's authoritative images proved very popular among later authors, who used them freely in their own pilgrimage accounts.

Figure 4. Illustration of Zante in Jean Zuallart's Il devotissimo viaggio di Gerusalemme (1587), p. 81. Image courtesy of Sylvia Ioannou Foundation.

One such was George Sandys, who reproduced over twenty images based on Zuallart in the third book of his account, devoted to the Holy Land. Indeed, borrowing and adapting images was a familiar practice of authors and publishers in the early modern book trade. In this case, however, this indicates that the two publications shared quite a lot of common ground. Sandys left England in 1610 for an extended tour that took him to France, Italy, Istanbul, Egypt, the Holy Land, and back to Italy. As opposed to Zuallart, Sandys was primarily concerned with the classical tradition, as his ample quotations in Greek and Latin and his keen engagement with monuments and ruins attest. His descriptions of contemporary Istanbul and Cairo and his treatment of Islam are elaborate and aimed at a public attuned to political, ethnographic, and natural-historical observation. And yet, the Holy Land and sacred history were also major focal points of his journey and its construction in print. Sandys, son of the Archbishop of York, made sure he was present in Jerusalem during Holy Week, 1611. He was not the only one; individual scheduling had become easier and more flexible once pilgrims were not dependent on the Venetian seasonal pilgrimage packages.Footnote 46

The appreciation of the Holy Land as a landscape had Protestant antecedents too: the Lutheran apothecary Leonhard Rauwolf (1540–96)—generally critical of pilgrimage and ranting against papists—acknowledged the efficacy of holy places in general and of Calvary in particular to “stir up affections in every true Christian who stands there and remembers the crucifixion, death, burial, and resurrection.”Footnote 47 Understanding the physical outlook of the Holy Land could help in getting salvation history right, and getting salvation history right was not that far from faith through which one could be justified. Sandys, in other words, was part of a culture and a tradition. His mockery of Catholic practices and the begging friars in Jerusalem is matched by respectful piety and sentiments aroused by his presence on site.Footnote 48 Sandys toured Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and environs, and produced a highly detailed account of the sites, with the occasional snide remark.

Clearly Zuallart and Sandys had very different attitudes toward pilgrimage. The former defended the institution and dubbed his voyage “devotissimo”; the latter embarked on an extended humanist-antiquarian grand tour. But such a quick comparison of the two linked publications—Sandys had clearly read and mined ZuallartFootnote 49—should not measure and grade the religiosity and authenticity of the pilgrim experience. Rather, if one looks beyond confessional fences and stated dogmas, both travelers convincingly represent an early modern Odysseus, both pious and curious. The two voyages rely on and continue the same literary tradition. More broadly, the early modern Jerusalem narrative, in text and image, was akin to emerging topographical genres. Some scholars have interpreted this as a sign of decay and of rising mundane secularism in the genre. We see it as a sign of vitality and rapid adaptation to the period's conventions. Thus, the Mediterranean was a physical and representational medium that early modern pilgrims traveled. Moreover, we claim, pilgrims and their accounts shared a broader cultural sphere of texts and methods with humanists and theologians. Classical erudition, antiquarianism, and biblical scholarship were all part of this common, cross-confessional stratum. In turn, biblical scholars, both Catholic and Protestant, read pilgrimage accounts as an important source of information on sacred history and geography. The following section looks more closely at the pilgrimage-related reading and writing practices of some Reformers and humanists.

PILGRIMAGE WITHIN HUMANIST AND REFORMIST SCHOLARSHIP

“As for the tomb in which the Lord lay, which the Saracens now possess, God values it like all the cows in Switzerland.”Footnote 50 Such was the giveaway remark by an agitated German Augustinian monk in 1519. Repeated with gusto for almost a century now as evidence for the end of pilgrimage, this bon mot can hardly stand as representative for Martin Luther's (1483–1546) stance on the Holy Land in general and even less for the broader range of Protestant positions on pilgrimage. Even if it were true that Luther and other Protestant Reformers consistently conceived of the Holy Sepulcher in bovine terms, this would not automatically articulate what most Protestants felt or did, as utterances by theologians do not necessarily reflect what happened on a more pedestrian—in every sense of the word—level.Footnote 51 Rather, early modern remarks about the decline of pilgrimage were a standard trope within the period's polemics. They should be studied as speech acts directed against the papist or heretical enemy, respectively.

The other side of the confessional divide basically agreed, in either mournful or triumphant modes. Thus, the travelogue of two Catholic pilgrims of 1608 from Solothurn, after describing the various Christian sects in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and mentioning “the Turks, the Moors, and the Jews” present in Jerusalem, reassuringly added, “You won't find Lutheran devils in Jerusalem since they stay in our countries.”Footnote 52 Like Zuallart, the Solothurn pilgrims interpreted the claimed Protestant absence at the Holy Sepulcher as an indication of their lack of piety and, in effect, as proof of the essentially non-Christian nature of Protestantism, making them worse than Muslims and Jews. The French naturalist Pierre Belon (1517–64) and the recent convert to Catholicism Prince Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł (1549–1616) had argued along the same lines some decades earlier.Footnote 53 Catholic polemicists mourned the harsh effects that the new irreligion had brought upon the voyage. Greffin Affagart—a noble Norman who had been to Jerusalem twice, in 1519 (aboard the same ship as Falck) and again in 1533—did not hold back: “Since that mean bastard Luther reigned with his accomplices and also Erasmus, who, in his Colloquies and Enchiridion, has blasphemed the voyages, many Christians have withdrawn and cooled down from it, especially amongst the Flemings and Germans who once were the most devout to travel.”Footnote 54 Affagart (and many modern scholars with him) mistook for a general trend what in fact was a personal impression of two very uneven years. His rhetoric should be taken with a pinch of salt. People of other times and persuasions made different statements. The German apothecary and traveler to the Levant, Reinhold Lubenau (1556–1631) from Königsberg, shrugged off a proposition to visit the Holy Land with the remark that “journeys to Jerusalem are nowadays so common that you won't impress anyone by having been there.”Footnote 55

In sum, the modern scholar reads different signs when sifting through sources on the practice and value of sixteenth-century pilgrimage. This can be true even with sources by one individual. A more nuanced utterance on the Holy Land is documented from Luther in 1530, when he dedicated his exposition of Psalm 117 to the noble Hans von Sternberg (d. 1535), who had gone on a pilgrimage to Santiago and Jerusalem in 1514.Footnote 56 In the dedication, Luther explicitly stated that he did not disdain pilgrimage to Jerusalem and even expressed his wish to visit himself. In lieu of this unfulfillable wish, Luther reveled in hearing and reading about such travels.Footnote 57 Hence, even if one condemned pilgrimage per se, this did not preclude travel to the Holy Land or interest in the Holy Land as such. Some knowledge of the Holy Land was indispensable for the understanding of scripture.Footnote 58 This understanding itself could be used as a polemical term by Protestants, to distinguish their motive from the alleged superstition and busy collecting of indulgences by Catholic travelers.Footnote 59 Also, Rome and indulgences were not the only enemies Luther faced: facing the threat of the Turk, some Crusader rhetoric could come in handy.Footnote 60 And while some of Luther's most efficient punchlines involved the ridicule of relics, Lutheran princes and nobles did not disown their pre-Reformation pilgrimages. They themselves treasured their Holy Land memories and even commissioned costly works of art that immortalized them.Footnote 61 From Lutheran Denmark and Norway—where, in contrast to Sweden, pilgrimage had never been formally forbidden—mostly young men continued to travel to Jerusalem.Footnote 62 Often considerations of career fused with Crusader ideology. In Tübingen, Lutherans were engaged both in studying past pilgrimages and in going on pilgrimage themselves. Besides gathering information on recent Greek pilgrims to Jerusalem, Martin Crusius (1526–1607) was excerpting Eberhard im Bart's account of his 1468 pilgrimage. Salomon Schweigger (1551–1622) published his own travelogue, which contained not only diplomatic copies of Ottoman documents but also a reproduction of the Franciscan friars’ sealed pilgrimage certificate.Footnote 63

The interest in pilgrimage literature and the Holy Land can also be explained with new humanist interests and with the smoldering urge for holy war. In pilgrimage literature, the two could become indistinguishable. The Crusade literature on Eastern Christianity, Islam, and Judaism had described the East in heresiological terms without disowning the older cosmographical tradition.Footnote 64 In overdue new studies on Bernhard von Breydenbach, Timm and Ross have situated the Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam and its extensive section on the peoples of the Levant in the context of Dominican learning, late medieval Kreuzzugsgedanken (ideas of Crusade), and post-conciliar heresiology.Footnote 65 Ethnography in Breydenbach is not the result of a slackening of religion giving way to curiosity about others, but instead of a heightened awareness of heresy. Kathryne Beebe has similarly embedded Felix Fabri in a context of Dominican learning and late medieval piety.Footnote 66

Historians of early modern scholarship and science have also challenged the dichotomy between pilgrims’ piety and new observational practices. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, pilgrims with their accounts took an active part in the creation of a massively expanding corpus on the geography of the Holy Land, biblical scholarship, and history.Footnote 67 Catholic and Protestant scholars not only helped themselves to the corpus of available late medieval and contemporary pilgrimage accounts but also perpetuated the genre of pilgrimage literature, as will be shown in the case study on Bünting below.

New science and traditional pilgrimage literature also coalesced with regard to the importance of measuring and autopsy (looking at something for yourself).Footnote 68 The need to see and touch for yourself harkens back to biblical motifs and is central to many Christian pilgrimage accounts, even of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages.Footnote 69 In early modern pilgrimage culture, these traditions were in dialogue with cutting-edge antiquarian approaches to the study and documentation of material objects. There is an observable antiquarianization of pilgrim practices in the sixteenth century: traditional tokens from the Holy Land such as palm fronds and water from the Jordan are joined by coins, artifacts from antiquity, and rare substances. Peter Villinger (d. 1581), a priest from central Switzerland who had fallen captive to the Ottomans on his way home from Jerusalem in 1565, mentions in his pilgrimage account that as a forced laborer in İzmit he had to prepare a construction site for his master. As they were digging, they “found beautifully worked marbles and other stones of the decayed city . . . and other beautiful antiquities such as copper coins that had been minted years ago by the Empress St. Helena, by her son Constantine, by Emperor Maximianus, Maximinus, Licinus, Dicletianus, Valentinianus, Theodosius, and others. Some of these I have brought home with me.”Footnote 70 Apothecaries, alchemists, and surgeons figure prominently too among pilgrims and organizers of pilgrimages in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote 71

While interest in the Holy Land and pilgrimage literature was widespread among scholars, it was not shared unanimously. Like Luther, Erasmus is often quoted as a major opponent of pilgrimage. This case may be more convincing. For example, in the preface to Annotations on the New Testament, Erasmus hypothesized about the reverence that would be due “to the sayings of Christ would they exist, preserved in Hebrew or Syriac, that is in the very words in which he uttered them. Who wouldn't be eager to linger over every tittle?”Footnote 72 He then bemoans the fact that Christ's earthly remains, his garment and footprints, receive more veneration than his words. In truth, Erasmus did not care too much for Jesus's vestiges in the Holy Land, nor about his original words, as his uninterested handling of the ipsissima verba, the few utterances in Aramaic recorded in the New Testament, reveals.Footnote 73 Erasmus had little sympathy for Syria and he liked best its inhabitants—whether Jesus of Nazareth, Lucian of Samosata, or Jerome—when they spoke or wrote in Greek or Latin.

However, the prominence, eloquence, and sheer mass of Erasmus's writings have seduced many into taking his utterances, if not at face value, then at least as representative of an entire sociocultural group—the somewhat amorphous cloud of humanists. This is misleading. While Erasmus did not care for either Christ's footprints or his Semitic utterances, others did, and they thought that in order to learn his language it might be advisable to follow his footsteps. A case in point is Guillaume Postel (1510–81), a well-connected, if eccentric, member of the republic of letters. While his mysticism—which some contemporaries identified as madness or heresy—was peculiar, his eager research in Oriental languages, biblical geography, and Christian Kabbalah was not. Sent to the Levant by the Venetian editor Daniel Bomberg (ca. 1483–ca. 1549), he stayed in Jerusalem with the Franciscans on Mount Sion.Footnote 74 In a letter of 1549 to his former student in Arabic, Andreas Masius (1514–73), another pioneer of Syriac studies in Europe, Postel showed himself in awe of “Holy Syria, the place that Christ himself has consecrated through his presence and shedding of blood.” Moreover, he was impressed as both a scholar and a believer by the many books in “Chaldean,” which he identified as “the language that Christ spoke.”Footnote 75 Postel thus combined innovative linguistic research with travel to the Holy Land. In so doing, he not only made use of the pilgrimage infrastructure as established by the Franciscans but also showed symptoms of the ideal pilgrim as the sanctity of the place and its relevance in salvation history washed over him. Several portraits, the oldest dating back to the late sixteenth century, show him with a large Jerusalem cross on his chest (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Portrait of Guillaume Postel by Jean Rabel, ca. 1595. British Museum, London, R,6.14. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Postel was not the only one who provided Masius with firsthand information on the Holy Land. Masius's correspondence of the 1540s shows other instances of how intertwined the spheres of travel and scholarship were. In his later years, Masius was corresponding intensely on the geography of Palestine with none other than Gerard Mercator (1512–94).Footnote 76 In the year 1546, Masius was corresponding with Jost von Meggen, an erudite magistrate in Catholic Lucerne and soon to be commander of the pope's Swiss guard. In one letter, Meggen, who had visited Jerusalem in 1542 and become a Knight of the Holy Sepulcher, asks Masius to review his travelogue—written, according to him, in a pedestrian Latin—in order to get it ready for print. Incidentally, Meggen remarks that the text he sent to Masius was already amended by none other than the Zurich Reformer Heinrich Bullinger (1504–75), but Meggen still asked for a proofreading by Masius “because in everything I prefer to follow your advice rather than his.”Footnote 77

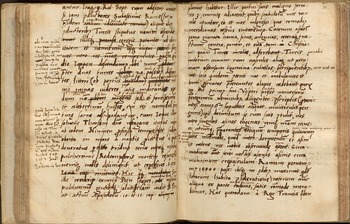

Needless to say, Meggen had expressed himself differently when he had written to Bullinger directly a few weeks earlier and thanked him warmly for the care he had shown for “my trifles.”Footnote 78 In the extant manuscript of Meggen's account, Masius's corrections (mostly stylistic in nature) are still visible (fig. 6).Footnote 79 Yet a couple of years later, when Meggen was already dead, the travelogue was still not in print. In 1563, the Swiss humanist and politician Aegidius Tschudi (1505–72) asked for the manuscript. He had to work hard to obtain the codex from the heirs.Footnote 80 Tschudi was probably interested because he himself was about to edit a pilgrimage account, written by his late brother Ludwig Tschudi (1495–1530), who had visited Jerusalem in 1519 in the company of Falck. Probably under Aegidius Tschudi's hand, his late brother's travelogue transformed into a learned tract on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Jost von Meggen's travelogue was eventually published in 1580, including the comments of unnamed but “very learned men,” as the editor remarks in the preface.Footnote 81 By that time, Meggen's pilgrimage account had already been read, corrected, and annotated so intensely by several scholars that the printer felt the need to exculpate himself on the last page by pointing out the sorry condition of the master manuscript. A quarter of a century after Meggen's death, the heavily redacted Tschudi travelogue also finally appeared in print in yet another redaction.Footnote 82

Figure 6. Jost von Meggen's pilgrimage account, with corrections by Andreas Masius. Zentral- und Hochschulbibliothek, Lucerne, MS Pp 21 4°, fols. 33v–34r.

The heavy revisionary work on travelogues may appear to undermine our claim to the importance of autopsy, mentioned above. Contemporaries saw it otherwise: it was precisely the redaction of texts that rendered them more accurate. In a postscript, possibly added posthumously by his brother Aegidius, Tschudi states: “Above, the holy places have been described that I, Ludwig Tschudi of Glarus, have visited and seen for myself and the marvels that I have experienced. I was helped by the published pilgrimage accounts of Bernhard von Breydenbach and Felix Fabri. Both of them former pilgrims too, they reminded me to inquire constantly and to check everything for myself. I have found everything to be as they describe it. In addition, I have added information on things they do not cover.” Tschudi goes on to say that this additional information stems from his learned fellow traveler Marcantonio Landrini (fl. 1519) from Milan, from Burchard of Mount Sion (traveled late thirteenth century), and “from other, more recent eyewitnesses.”Footnote 83

Meggen's pilgrimage account was not the only one Bullinger took care to read, nor was he the only one in Zurich to take an interest in the Holy Land. It is likely that Bullinger had some knowledge of the travelogue by Wölfli (of which more below), with whom he stood in good contact. That he also appreciated other pilgrimage literature one can know for sure because he wrote “You'll find a lot of relics in this book” on a codex that, besides notes on Ottoman conquests and excerpts from Breydenbach's Peregrinatio, also contains the substantial pilgrimage guide to the Holy Land by Wilhelm Tzewers (1420–1512).Footnote 84 Before Bullinger, Peter Falck (see above) had already used that very same codex to prepare himself for his second pilgrimage to Jerusalem and, on that occasion—based on his first pilgrimage—corrected Tzewers's description of the graves of the Crusaders Godfrey of Bouillon (ca. 1060–1100) and Baldwin I of Jerusalem (d. 1118).Footnote 85 All this is to underline that pilgrims and pilgrimage were part of the normal erudite circulation within the republic of letters, transcending religious divides effortlessly in both past and present.

After having reviewed the interest of Luther, Bullinger, and Masius in pre-Reformation or Catholic pilgrimage to Jerusalem, let's look at how a recent pilgrimage to Jerusalem was committed to memory in a Calvinist humanist context in Bern.Footnote 86 Heinrich Wölfli (1470–1532), the Bernese canon and former teacher of Huldrych Zwingli, traveled to the Holy Land in the years 1520–21.Footnote 87 Back in Switzerland, he became a supporter of the Protestant Reformation and got married. His travelogue is lost in its original Latin version. A German translation, however, was accomplished in the year 1583 by Johannes Haller, a Calvinist pastor, who also had it lavishly illustrated by a local artist.Footnote 88 It has to be considered as a scribal publication, for it comes with a title page, complete with place and year, and with a preface (actually a dedication) by the translator. In the preface, Haller quotes his brother-in-law Abraham Musculus (1534–91), a leading figure of the Calvinist ecumene of the later sixteenth century, who claimed to have read “many accounts of such journeys but none that could match this one in skill and eloquence.”Footnote 89

What the case of Wölfli shows is that travel to the Holy Land was thriving at the dawn of the Reformation, not just among credulous believers or conservative clergy but also among the leadership of the reform movement and humanists sympathetic to it. In that regard, Wölfli is akin to Falck, whose grave in Rhodes he visited and mentioned.Footnote 90 After the consolidation of the Reformation, there seems to have been nothing humiliating about recounting a sacred journey in one's biography—quite the contrary: Protestant dignitaries invested themselves in the textual traditions of such accounts. In the process of translation, the Calvinist pastor Haller may have accentuated some anticlerical or anti-Roman features of Wölfli's account—such as the distrust of the friars’ selfless charity in Jerusalem and some more aggressive anticlerical remarks in the context of Venice and Rome, where Wölfli kissed the pope's feet twice but called him an “idol” and Rome a “new Babylon”Footnote 91—but the journey itself and its religious dimension were not disavowed and the account continued to be copied. The illustration in the Wölfli-Haller account of the accolade when one of Wölfli's travel companions was awarded the knighthood of the Holy Sepulcher has become almost iconic, illustrating recent histories of pilgrimage and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (fig. 7).Footnote 92

Figure 7. The accolade at the Holy Sepulcher as imagined by an unknown illustrator. Burgerbibliothek Bern, Bern, MS h.h.XX.168, 192–93.

To be sure, the vituperations of some humanists and almost all Protestant Reformers against pilgrimages indicate some radical reorientation within theology and intellectual history. Yet these pronouncements also stand in a tradition of polemics reaching back as far as the church fathers and occasionally repeated by the pilgrims themselves. The Reformers’ criticism also indicates the prevalence of the phenomenon they denounced. Moreover, we doubt that they reflect the overall value that was assigned to pilgrimage to Jerusalem or the Holy Land. Probably to the chagrin of its critics, travel to the Holy Land, both in practice and in representation, was and remained part of the fabric of religious, cultural, and erudite life in early modern Europe.

MEMORIALIZING PILGRIMAGE

That pilgrimage to Jerusalem was a vital part of noble or would-be noble self-representation around 1500 is well established. The provisions made by Falck for his own chapel within the collegiate church of St. Nicholas provided us above with a first impression. In relation to Nuremberg families, a German historian has even created the apt (and slightly awkward) neologism Jerusalempilgergeschlecht (dynasty of Jerusalem pilgrims). Discussing the Ketzel family, he states that in the sixteenth century—when both their city and the Ketzels had become Protestant—pilgrimage to Jerusalem was out of the question.Footnote 93 Even if that were true (see below the case of a Protestant pilgrim from Nuremberg), a strong stance against pilgrimage would have been disadvantageous to many of the most established and powerful families, given the importance of family history for social advancement within early modern cities. Their social capital in no small measure consisted in ancestral pilgrimages, remembered by means of family archives, buildings, tombstones, coats of arms, paintings, and other material expressions. Rather than disown past pilgrimages, Protestant elites preserved and even fostered their memory. At the end of the sixteenth century, the Nuremberg noble Hans Rieter (the younger, 1564–1626) collected ancestral pilgrimage accounts in a book.Footnote 94 Members of other distinguished or aspiring families in other cities did the same.

In the following, the discussion focuses on three pilgrims from the beginning of the sixteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth to illustrate how past pilgrimages took a central role in the construction of aspiring civic identity, even in societies in which pilgrimage as a means for salvation was shunned. The term secularization would not do justice to the process, as the religious undertones of these journeys were not suppressed; rather, these families were proudly showcasing the piety of their traveling forebearers and relatives.

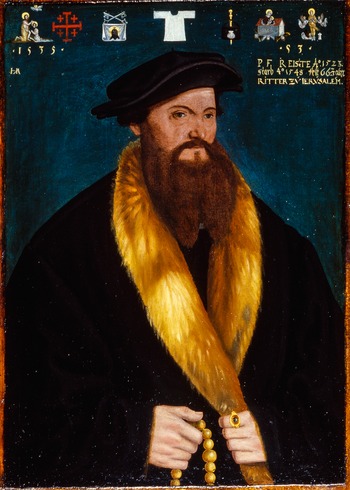

Peter III Füssli (1482–1548) was born in Zurich into a family of bell founders, a trade he would continue. Already a member of the city council of newly Protestant Zurich, Füssli went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1523. Füssli was part of the very same party of pilgrims as Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556).Footnote 95 Füssli arrived safely back in Zurich the next year. In the Battle of Kappel in 1531, when Zurich fought against Catholic Swiss cantons, Füssli acted as a commander of the city's artillery. The following year, Füssli attended mass in nearby Einsiedeln, the most prestigious pilgrimage destination in Switzerland, and was duly fined by Zurich's city council. In 1535, Füssli had his portrait painted by the locally renowned Zurich artist Hans Asper.Footnote 96 In the portrait, Füssli is shown holding a rosary (fig. 8).

Figure 8. Portrait of Peter III Füssli (1482–1548) by Hans Asper, 1535. Kunstmuseum Solothurn. Image provided by SIK-ISEA, Zurich.

Obviously, Füssli adhered in some way to Catholicism well beyond the Reformation. One might argue that his Jerusalem pilgrimage during the Reformation was simply bad timing. Attending mass almost ten years later, however, clearly indicates stubborn adherence to forms of piety that had become obsolete and, in fact, illegal. After all, a Catholic army had defeated Zurich and desecrated Zwingli's body at Kappel just the year before. Maybe the Zurich authorities grudgingly tolerated the Catholic sympathies of an old man—even if lenience was not known as their strongest virtue in other cases. But this would not explain the active perpetuation of Füssli's pilgrimage to Jerusalem by his own kin. Before 1700, there are four known manuscript versions of Füssli's travelogue and one copy of Asper's portrait of him as a pilgrim.Footnote 97 Over a century later, in the highly confessionalized context of seventeenth-century Zurich, the memory of Füssli's Jerusalem pilgrimage was still maintained. The professor of theology Peter IX Füssli (1632–84) collected and copied documents of his ancestor's journey in his family book. Among the materials collected is a short, rhyming history of the family in which the Jerusalem pilgrimages of both Peter I Füssli (d. 1467) and Peter III Füssli are seen as proof of the ancestors’ piety. Of Peter I Füssli it reads as follows:

Of Peter III Füssli, the poem says:

The respective lines of the poem are decorated with a Jerusalem cross in the margins. The book also contains Peter III Füssli's pilgrimage certificate of 1523, issued by the Franciscan Custody in Jerusalem, both in original and in copy.Footnote 100 A list there also specifies the relics that Peter Füssli had brought back from the Holy Land and states that some were still extant, among them two waxen Agnus Dei. It is freely admitted by Peter IX Füssli that the Agnus Dei and other pilgrimage relics were handed down “from an era of dark popery.”Footnote 101 Nevertheless, they served to underline the family's dignity and claims to power within the city state.

Peter IX Füssli adorned his ancestors’ pilgrimage writings with bibliographical references to the pilgrimage account of Hans Tucher (1428–91) and to the scholarly works of Heinrich Bünting (1545–1606) and Sebastian Münster (1488–1552).Footnote 102 Another reference in the Füssli book is to professor Johann Heinrich Hottinger (1620–67), a Zurich theologian, historian, and Oriental scholar of international fame.Footnote 103 The reference informs us that Hottinger had in his possession one of the Agnus Dei that Füssli had brought back from Jerusalem.Footnote 104 The reference is to Hottinger's Wägweyser (Signpost), a book of confessional polemic in which Hottinger decried the belief that those medallions, “made of wax and balm,” should have power to annihilate sins, ease deliveries, drive out bad weather, and protect from fire and water.Footnote 105 Hottinger mined the Füssli book for material evidence of what he considered papist superstition. In a printed guide to Zurich's libraries, Hottinger mentioned the Füssli travelogue. He quoted from both Füssli's pilgrimage certificate and from the Franciscan recipe for the production of Agnus Dei.Footnote 106

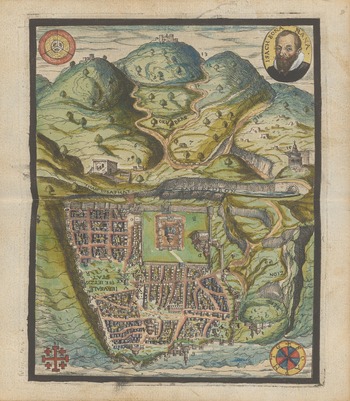

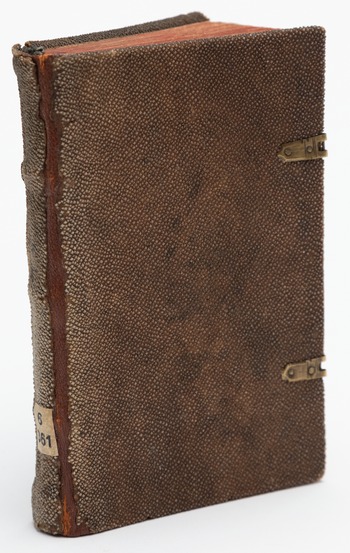

Füssli's travelogue also served to inform Hottinger, the stay-at-home Orientalist, about Levantine culture: “I have learned from it that Turkish and Arab robbers constantly lie in wait for travelers’ possessions. Not even wine is safe from them, although Muhammadism forbids its consumption.”Footnote 107 Hottinger also learned from other pilgrimage accounts. In that same library guide, Hottinger presents two other pilgrim writers from Zurich. One is the famous late fifteenth-century Dominican friar Felix Fabri. The other is the early seventeenth-century barber-surgeon Hans Jacob Ammann (1586–1658). Ammann had traveled “to the Promised Land” in 1613 and his travelogue had been printed in Zurich in 1618 and in 1630.Footnote 108 Hottinger, in his library guide, praises the Ammann itinerary for being “most perspicuous in its presentation of the institutions and culture of the Turks and of the state and local conditions of the Orient.”Footnote 109 Unlike Fabri and Füssli, Ammann was definitely no Catholic—he had an inclination to religious nonconformism and Paracelsianism. Nevertheless he embraced the insignia of Catholic pilgrimage to the Holy Land: his travelogue includes a Zuallart-inspired map of Jerusalem and is adorned with his portrait and the Jerusalem cross (fig. 9).Footnote 110 His nonconformist beliefs—which included the hypothesis that Muslims could be saved—had brought Ammann into conflict with the authorities in Zurich.Footnote 111 Probably in reaction to that, Ammann in the second edition of his travelogue (1630) pointed out the religious tolerance he encountered in the East: “how astonishing is God's management of the world that many different peoples live under such an un-Christian potentate: Christians, Jews, and others, throughout his empire. They enjoy his protection and live and do business right beside the Turks. Everyone is free to live according to his faith and conscience.”Footnote 112 Ammann also mentions the tolerance practiced by the Franciscan friars toward visitors of other creeds.Footnote 113 Like Füssli a century before him, Ammann carefully kept his pilgrimage certificate. In his printed travelogue he reproduced it diplomatically in Latin and provided a German translation.Footnote 114 Of the travelogue itself, he donated a shark-skin-clad copy to the city's library and Kunstkammer (fig. 10), together with an Italian copy of Zuallart, stones and artifacts collected in the Levant, and books by Paracelsus.Footnote 115 The safeguarding of the Füssli family memory was connected to pilgrimage research, antiquarian study and collecting, anti-Catholic polemic, and more recent Levantine travel. All the while Catholic superstition was attacked, the Franciscan-issued pilgrimage certificate and relics served to substantiate and authenticate familial claims and credibility.

Figure 9. Colored map of Jerusalem with Hans Jacob Ammann's portrait (anagrammatically labeled as “Isach Bona Mana”). Zentralbibliothek Zürich, 6.361.

Figure 10. Hans Jacob Ammann's shark-skin-bound copy of Reiß ins Globte Land (1630), donated as a gift to the Burgerbibliothek. Zentralbibliothek Zürich, 6.361.

Was there a special Protestant way of engaging with relics? All in all, it is surely safe to say that Protestants had no interest at all (at least if one can take them by their word) in indulgences, and even less in Christian architecture. In contrast to Zuallart and others, they preferred the landscape as such as an object of reverence or a catalyst of devotion. Also, they had problems with relics produced by the Franciscan Custody (such as Agnus Dei) and, as Ammann, preferred to collect fruits, plants, and stones.Footnote 116 Then again, botanical and geographic interest in the Holy Land was by no means limited to Protestants but encompassed also Catholics and especially Franciscans.Footnote 117 Also, bringing back fruits and other natural products from the Holy Land was a continuation of the very old tradition of bringing home eulogias (blessings).Footnote 118

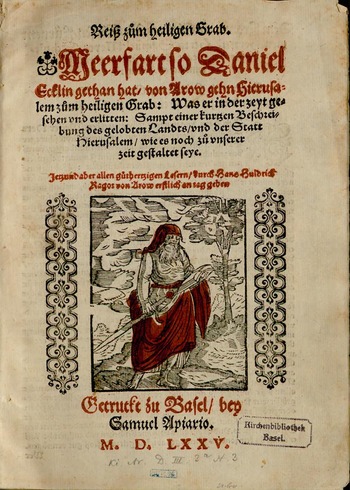

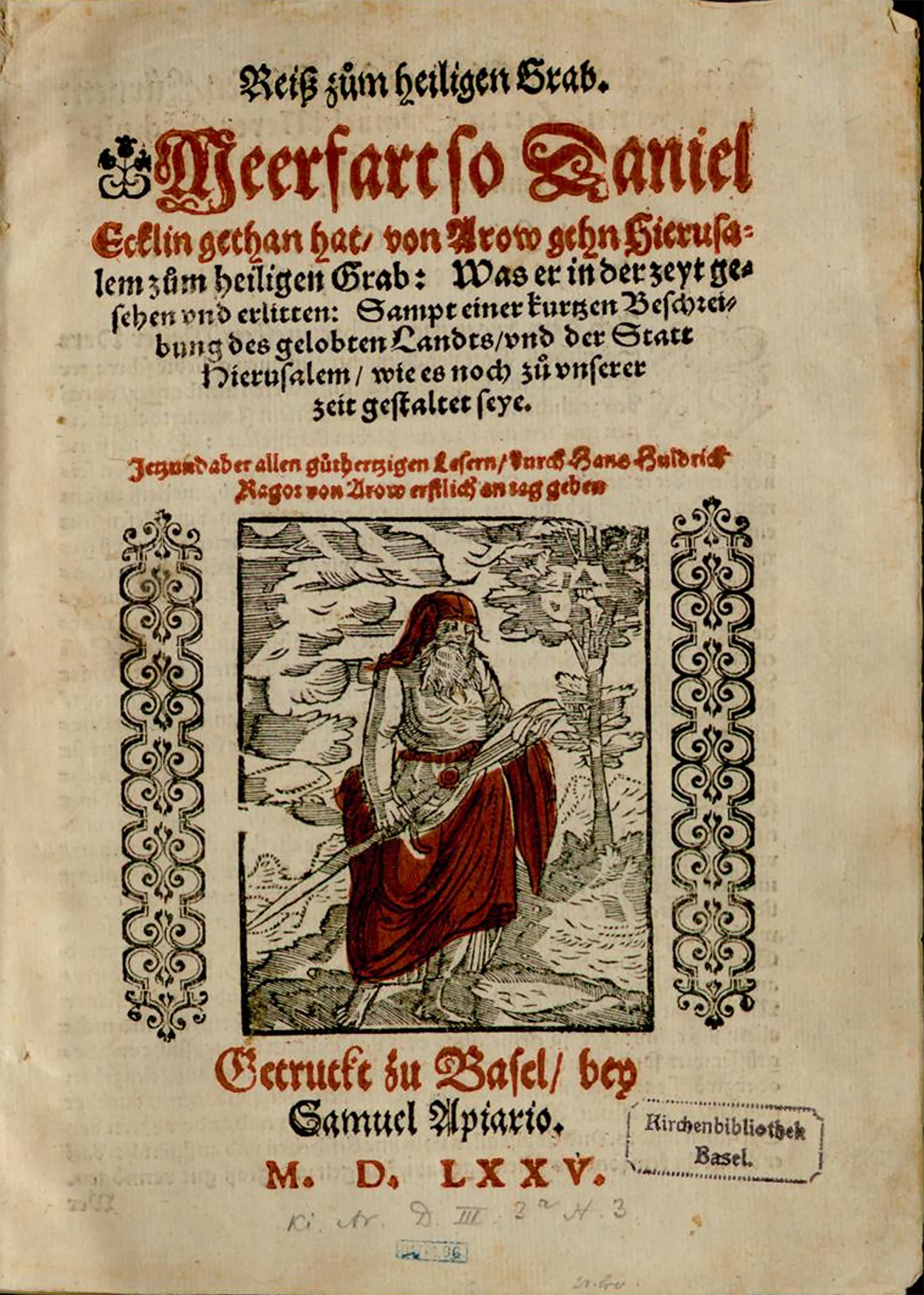

Another case that demonstrates the modalities of Protestant interest in pilgrimage is that of the journeyman apothecary from Aarau, Switzerland, Daniel Ecklin (1532–64). Ecklin was not the typical pious pilgrim, seeking at all costs to reach the Holy City. Rather, he seems to have ended up there haphazardly, as a station on his impromptu voyage. Ecklin's travelogue was only published posthumously in order to honor his memory, as he died at a young age. The textual editing and the edition were the work of Daniel's brother, Gabriel, another apothecary, and his brother-in-law, a Calvinist pastor. The pastor also made Daniel's pilgrimage acceptable for an audience of Protestant faith as, according to him, Daniel wanted to see for himself the places known to him from holy scripture.Footnote 119 The first edition appeared in 1574 in Protestant Basel. Subsequently, Ecklin's account would be republished almost forty times over the next two centuries, including in Feyerabend's famous collection of Holy Land travel of 1584.Footnote 120 As early as the first edition, Ecklin's pilgrimage certificate as issued by the Custody of the Holy Land was quoted in full in German translation at the end of the travelogue. The reason for this, so we are told, was to allay suspicion, “as widely traveled journeymen often encounter disbelief back home.”Footnote 121 The religious aspect of Daniel's pilgrimage, the travel to the Holy Sepulcher, came even more to the fore in a new edition of 1575, when the title was changed. While it had been Wandel oder Reißbüchlin (Travelogue), it now became Reiß zum heiligen Grab (Journey to the Holy Sepulcher) (fig. 11). Thus, a Jerusalem journey by a Protestant was gradually molded into a pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulcher by the traveler's Protestant relatives.

Figure 11. Title page of Daniel Ecklin's Reiß zum heiligen Grab (1575). Image courtesy of e-rara.ch.

A similar case is found in the Nuremberg magistrate Lukas Friedrich Behaim (1587–1658).Footnote 122 There, too, a somewhat accidental visit to Jerusalem was remembered as a fully fledged pilgrimage in a seventeenth-century Protestant context. Behaim's eulogist explicitly stated that the Nuremberg lore of traveling nobles animated him to travel to Jerusalem. Like Sandys, who had arrived a few months earlier, Behaim can be found in the Franciscans’ guestbook in 1611. Unlike Sandys's, Behaim's name was not awarded the epithet hereticus.Footnote 123 While Constantinople rather than Jerusalem was aimed at in the beginning, rumors about the Plague raging at the Golden Horn had the voyagers change their plans on Zakynthos.Footnote 124 Notwithstanding the impromptu nature of the trip, Behaim fashioned himself (and had others fashion him) as an unabashed Jerusalem pilgrim. His pilgrimage is attested to in at least five different ways: letters sent home, a pilgrimage certificate, his own travelogue, a funerary sermon, and a portrait. From Venice, Zakynthos, and other places, he wrote letters home to his father, who archived them and duly noted their receipt. Back home he drafted an autobiographical account of his travels, including the journey to the Holy Land.Footnote 125 After his death, Behaim's pilgrimage to the Holy Land was immortalized in word and image: the pastor Martin Beer (1617–92) added a lengthy biographical appendix to the printed eulogy in which he highlighted Behaim's journey to the Holy Land. The artist Georg Walch (1612–56) placed three Jerusalem crosses in Behaim's copperplate print portrait: one below the coat of arms, one on the heraldic helmet, and one on Behaim's ring (fig. 12).

Figure 12. Portrait of Lukas Friedrich Behaim by Georg Walch, 1648. Image courtesy of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

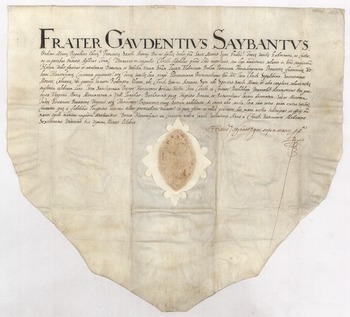

In retelling the encounter with the Franciscan friars of the Custody of the Holy Land, Behaim stresses his unwavering Lutheran commitment. Rather than being converted by an eager Spanish monk in Bethlehem, Behaim turned the tables and brought the latter to the brink of conversion to Protestantism. At the same time, Behaim underlines the harmonious company they shared with their Catholic hosts. Rather than being shy about the Catholic nature or pilgrimage aspect of the journey, Behaim mentioned in his travelogue that after their stay in Jerusalem they “received presents, certificates, and some relics from the friars. We bid them good bye and rode back through Rama to Jaffa.”Footnote 126 Behaim's personal pilgrimage certificate, issued by the Franciscan Custodian Gaudenzio Saibanti (d. 1612), is still extant and was preserved within the Behaim family's archive (fig. 13).Footnote 127 Behaim wrote to his father when he was back in Venice: “I don't have time and paper enough to report everything I saw in and around Jerusalem. My pilgrimage certificate will give evidence of the places I've visited in Jerusalem. I cannot boast too much with it here in Italy because it does not include the statement that I have confessed and received communion.”Footnote 128 Indeed, certificates issued by the same Custodian Saibanti to Catholic pilgrims or newly created Knights of the Holy Sepulcher usually included such a phrase and generally contained more text that linked the pilgrimage at hand to the history and heritage of the Crusades.Footnote 129 For Behaim, therefore, the pilgrimage certificate served multiple purposes: it could be read as an itinerary of his visit of the holy places; it proved that he was a genuine and traditional pilgrim to Jerusalem; at the same time it proved (from silence) that he had kept his Lutheran faith. Behaim was part of a tradition. He was at the time accompanied by compatriots and four years later his half-brother, Georg Hieronymus Behaim, would die on the way to Jerusalem.Footnote 130

Figure 13. Pilgrimage certificate issued by the Custodian Gaudenzio Saibanti for Lukas Friedrich Behaim, 1611. Stadtarchiv Nürnberg, E 11/I Nr. 204.

To say that Behaim and others performed pilgrimage to Jerusalem is not to say that we could not also think of those travels as part of the grand tour or an artisan's traditional Wanderjahre (journeyman years), with the friars’ certificate as the functional equivalent of an album amicorum (friendship book) or a distant guild's certificate.Footnote 131 Certainly pilgrimage and its institutions could and did serve such purposes too. It was not, however, absorbed by these other forms of travel. Rather, in a complicated way, Protestant travelers and their families at once continued, rejected, and transformed the tradition of pilgrimage.

PROTESTANT MENTAL AND LITERARY PILGRIMAGE

As the discussion above has shown, Lutheran and Calvinist attitudes to sacred geography and to the Jerusalem voyage were complex and often ambivalent. Clearly, however, for Protestant theologians and pilgrims alike, the Holy Land and the Mediterranean landscapes of the New Testament remained a focal point of scholarship and religious devotion.

Mental pilgrimage provides a particularly interesting perspective from which to explore the wide spectrum of early modern Protestant engagements with the Holy Land and pilgrimage to it. In the last two decades, historians of art, religion, and literature have paid significant attention to the rise of mental or spiritual pilgrimage in late medieval Europe and to its early modern afterlife.Footnote 132 The phenomenon is often related to conventual life, and to the practice of creating mental images of Christ's life and Passion, frequently with the help of real images, or by listening to and reciting texts. However, mental pilgrimage took other forms as well. First, individual laypersons were also encouraged to practice mental pilgrimages. In 1530, for example, the Carmelite Jan Pascha (fl. early sixteenth century) wrote an influential imaginary Jerusalem voyage in the form of a year-long spiritual diary, which was meant to be followed daily.Footnote 133 The French Jesuit Adrien Parvilliers (1619–78), who had visited the holy sites in 1654, published a successful guide to mental pilgrimage, which encouraged the devout reader to imagine a series of scenes and recite prayers along the Way of the Cross.Footnote 134 Secondly, mental pilgrimage was often part of the routine of physical pilgrimages, especially in the Holy Land. From late antiquity, pilgrims such as Egeria described how they had used their imagination to evoke biblical scenes while standing next to the real holy sites. Vicarious pilgrimages to Jerusalem, replicas, and sacri monti all over Europe are a related phenomenon, mixing the spiritual and physical.Footnote 135 Mental prayer and other devotional regimens, more broadly, were also forms deeply rooted in the sacred topography of the Holy Land and Jerusalem, as (the real pilgrim and shipmate of Füssli) Loyola's Spiritual Exercises (1548) make clear. Mental pilgrimage is therefore a multifaceted phenomenon which continued to thrive in early modern Europe. We wish to demonstrate that Protestants shared some of its premises and vocabulary.

For this purpose we would like to highlight Heinrich Bünting's work. Bünting was born in Hanover in 1545 and studied theology in Wittenberg, where he received the degree of magister in 1569. He was briefly a minister there and then moved to Gronau, where he wrote his two major early works: the Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae (Travel book of sacred scripture), on which the next pages focus, and a history of Braunschweig and Lüneburg.Footnote 136 These two works were later joined by a provocative chronology.Footnote 137 In 1591 he was named superintendent at Goslar. Following a theological dispute, however, he was removed from this office and returned as a lay person to his native Hanover, where he died in 1606.Footnote 138

Recent studies have looked mostly at Bünting's work in the field of chronology, where he is marked as an innovator who did not shy away from using astronomical records to settle scriptural issues.Footnote 139 Considering the Itinerarium's major success, modern scholarship has paid surprisingly little attention to it. The work appeared first in German (1581), prefaced by the eminent Lutheran theologian Martin Chemnitz (1522–86), and then, in much expanded form, in Latin (1597). Scholars have counted at least sixty editions between 1581 and 1757, in various European languages.Footnote 140 The Itinerarium today, however, is remembered mainly for one or two striking allegorical images that accompanied it, most famously its representation of Jerusalem at the center of a tripartite cloverleaf-shaped world (“Die gantze Welt in ein Kleberblat”—in fact, a playful heraldic homage to his hometown).

Often these representations are wrongly interpreted as an example of a lingering medieval world view, a late echo of the mappamundi tradition. The work itself, however, is a weighty and learned compendium of Old and New Testament geography and history, organized around the theme of travel. It became, especially since the greatly expanded Latin edition appeared in 1597, a highly respected source of valuable information about the Holy Land, based on a wide array of ancient, medieval, and early modern authorities. By emphasizing travel, Bünting echoed contemporary conventions in the rapidly developing genre of travel collections, of which Giovanni Battista Ramusio's Navigationi et viaggi (Some voyages and travels, 1550) was the most prominent example at the time.Footnote 141 Uniquely, however, Bünting uses the notion of travel in two senses: both as the readers’ literary, spiritual journey through the holy text, book by book, and, most strikingly, as a collection of scriptural (and by that fact, sacred) travel accounts. Bünting constructed travel narratives that portray biblical figures as constantly on the move and draw on the old notion of pilgrimage as a symbol of Christian life.

This notion is clearly central to Bünting's conception of his enterprise. As he wrote in the introduction to the first German edition, in a passage rife with biblical allusions, by contemplating travels of biblical figures, “we can mirror ourselves in their whole life as in a bright mirror, and thus learn from them what is good and what is evil, how we should live godly, … so that we may one day blessedly end this pilgrimage of ours and depart from this valley of tears and strange land, wherein we have been pilgrims and strangers, for the heavenly fatherland, and that we may together with all chosen holy people and angels, citizens and members of the household of God, may come to the new heavenly Jerusalem.”Footnote 142 Thus, beginning with Adam, Bünting walks his readers in the footsteps of many biblical figures using a set pattern. Let us follow Bünting's Joseph as a representative example. First, Bünting enumerates Joseph's movements, noting locations visited and distances covered. He begins with Joseph's search for his brothers in the field (15 miles, Gen. 37) to Joseph's eleventh and last journey from Hebron, where he had buried his father, to Heliopolis (50 miles, Gen. 50). Bünting concluded this section by adding up the distances—during his life, the readers learn, Joseph traveled a total of 240 miles. The section that follows focuses on the places visited by Joseph, for example, Dothan and Heliopolis, which are described with reference to additional biblical and extra-biblical sources. Bünting highlighted the meaning of place names as a kind of code for deciphering biblical narratives. He compares each one with its Greek and Latin variants and provides the literal meaning of the name in German.

By meticulously documenting places and calculating distances, Bünting was following the model set by several earlier sixteenth-century German scholars, most notably the Bavarian humanist Jakob Ziegler (ca. 1470–1549) and Kaspar Peucer (1525–1602), with whose work he was intimately acquainted.Footnote 143 Ziegler was active during the first decades of the sixteenth century. One of his notable publications was a biblical atlas formatted according to the principles of Ptolemy's Geography.Footnote 144 Ziegler, like Bünting after him, freely mixed pagan science with sacred history. Peucer, Melanchthon's son-in-law, whom Bünting very probably met in Wittenberg, wrote a treatise on geometry and measurement, which he thought essential skills for students of sacred history.Footnote 145 Bünting, too, in the preface to the reader, emphasized the importance of geography for the deeper and better understanding of scripture, and provided a short guide for geometrical measurement, together with a list of coordinates of biblical locations.Footnote 146

In the final section describing Joseph's itinerary, Bünting reflects on the “spiritual meaning of Joseph the Patriarch.”Footnote 147 He outlines dozens of parallels between the lives of Joseph and Jesus in order to establish Joseph as a near perfect prefiguration of Christ. For example: “Joseph was sent by his father to seek his brothers (Gen. 37). The Lord Christ was also sent by his heavenly Father into this world to seek again his brothers, the lost sheep of the house of Israel (Matt. 15).”Footnote 148 Thus, following Joseph's life, which had been arranged as a series of sacred travels, Bünting's readers were encouraged to imagine themselves, ultimately, as pilgrims in Christ's footsteps. Following this pattern, Bünting traced the journeys of each significant biblical figure, and thus in effect retold the whole canon in the form of travel account and gazetteer. His readers were asked to be precise readers of scripture and better understand its geography. On that firm basis, they were also asked to follow each figure's journey in their mind's eye and engage in a form of mental pilgrimage, which focused on spiritual and moral implications.

Bünting's is not the only sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century example of Lutheran explorations of mental pilgrimage. As Martin Christ has recently shown in his studies of Lutheranism in Upper Lusatia, similar ambiguities appear around Görlitz and its late fifteenth-century model of the Holy Sepulcher, which developed into a pilgrimage site. Following the Reformation, the place had been reinterpreted by the pastor Sigismund Suevus (1526–96), who published Geistliche Wallfahrt oder Pilgerschafft zum heiligen Grabe (Spiritual journey or pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulcher, 1573), a small book in which he combined civic pride related to the site with emphasis on the religious value of mental pilgrimage. The tract was dedicated to Georg Emerich, the grandson of Georg Emerich the Elder (1422–1507), who donated the money to build the replica, following his Jerusalem pilgrimage in 1465.Footnote 149 Following Bünting, the Lutheran preacher Johann Eger (d. 1613) published Itinerarium, das ist Reisebüchlein (1604), in which he followed in rhyming verse the travels of the Holy Family.Footnote 150 Protestants, then, and Lutherans in particular, were actively engaged with notions of mental pilgrimage as a method for the study of scripture, as a subject for intense exploration, and as a religious practice.

CONCLUSION: THE REFORMATIONS OF JERUSALEM

Pilgrim or traveler? Devout or curious? Catholic or Protestant? In this article we have tried to place these questions in their proper early modern context. For too long, we have argued, scholarship on pilgrimage and travel has taken such simple, dichotomous formulations as self-explanatory. These mutually exclusive labels were informed by and also reinforced metanarratives about modernity, secularization, and periodization that obscure rather than elucidate our understanding of the phenomenon. Based on the new scholarly consensus about the vitality of early modern pilgrimage to Jerusalem, our contribution has aimed to further develop these discussions by looking at its modalities. The series of case studies presented above demonstrates that pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the age of European Reformations was a broad field of practice and expression that cannot be disentangled from the social, religious, and learned history of the period. Our work also establishes the value of the qualitative study of this cultural field.

Surely pilgrimage was a contested field, too. Yet feuding Catholics and Protestants, of different shades, were in fact contestants in the same ring. Polemic on both sides was one of the ways to fashion one's genuine attachment to Jerusalem and the Christian memory it symbolized, both on the road and at home. During the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the period covered here, Europeans made sure to highlight their Jerusalem experiences by using a set of shared methods and genres—a visible practice involving both bodily and symbolic actions; the medieval tradition together with the new documentary practices of Mediterranean antiquarianism and the new science; classical heritage aligned with the novel rigor of biblical and Oriental erudition. In terms of social standing, the grand voyage was almost indistinguishable from the grand tour, as both served to establish one's status in civic and court life. Later generations in Protestant (both Lutheran and Calvinist) Europe continued with pride to archive and edit their pre- and post-Reformation forebears’ Jerusalem texts, insignia, and material souvenirs. Such texts in turn were in wide circulation in the republic of letters, of which travelers and pilgrims were members, too. Our generous and flexible definition of pilgrimage does not entail a smoothing out of all differences. We do not presume that a hypothetically representative pilgrim of the late Middle Ages felt or acted exactly as a Catholic or a Protestant pilgrim a century later. However, by thinking across periods, regions, confessions, and genres, the phenomenon emerges more clearly in its fullness—a robust and well-embedded practice of early modern society, culture, religion, and scholarship.