Introduction

“One Health” is still too much focussed on human health, without adequate consideration that people are one species in the panoply that is biodiversity. There is, thus, a global need for a radical change in thinking to position people, wildlife, and ecosystem health as mutual beneficiaries from societies’ investments and interventions. Here, we recognise wildlife as including the plant and animal kingdoms, and ecosystem health as effective ecosystem functioning. A recent example as to why this global need must be satisfied was the notification in March 2023 by the World Health Organisation (2023) that Tanzania had its first-ever outbreak of Marburg Virus Disease, initially transmitted to people from fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). While this event is as over, it is just one example in a series of wildlife-people disease spill-overs that demand global attention (e.g., Fauci, Reference Fauci2022). The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) noted that pandemic pathogens emerge from the microbial diversity found in nature, with 70% of emerging diseases in people, and almost all known pandemics, caused by microbes of animal origin (IPBES, Reference Daszak, Amuasi, das Neves, Hayman and Kuiken2020).

Observing that nature underpins all dimensions of human health, IPBES (Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo and Guèze2019) illustrated the negative impacts of multiple convergent and synergistic drivers, including climate change, on biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services. These negative impacts in turn contribute to poor human health. Key drivers of global change include plant and animal invasions; land use changes; agricultural intensification and the increase of unsustainable agriculture, forestry, and fishing practices; illegal wildlife trade; pollution; and water insecurity. Since the emergence of COVID-19, the rate and negative direction of these global changes continues to accelerate (e.g., IPBES, Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo and Guèze2019; Ndehedehe, Reference Ndehedehe2023; Obura et al., Reference Obura, DeClerck, Verburg, Gupta, Abrams, Bai, Bunn, Ebi, Gifford, Gordon, Jacobson, Lenton, Liverman, Mohamed, Prodani, Rocha, Rockström, Sakschewski, Stewart-Koster, van Vuuren, Winkelmann and Zimm2023). These global changes challenge the environment and people as the changes increase, become interconnected, and more complex. The siloed approach we have taken to the health of living things is now inadequate to meet the force of these challenges.

Zoonoses are increasing (IPBES, Reference Daszak, Amuasi, das Neves, Hayman and Kuiken2020) and have brought into particularly sharp focus the links and interdependencies of environmental, wild animal, livestock, and human health. These interdependencies present an immediate need to improve arrangements to better prevent, prepare for, and respond to, future pandemics and other health threats. IPBES (Reference Daszak, Amuasi, das Neves, Hayman and Kuiken2020) reported “One Health is a system of tackling key health issues (e.g., the emergence of pandemics) by recognising that the health of people, animals and the environment are inextricably linked; and by leveraging work in all three sectors to better address the proximal and underlying causes of health issues.” This definition was expanded by the One Health High-Level Expert Panel, OHHLEP, but all definitions emphasise the need for One Health approaches and their integrative nature (IPBES, Reference Daszak, Amuasi, das Neves, Hayman and Kuiken2020; OHHLEP, 2023).

IPBES (Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo and Guèze2019) underlined that Nature’s underpinning of specific health targets varies across regions and ecosystems and is influenced by anthropogenic activities through drivers of negative change; an influence that remains poorly studied. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the biodiversity-related Multilateral Environmental Agreements have been promoting transformative change (e.g., IPBES, 2021) to address drivers of negative change in the biosphere. This includes a focus on the drivers of disease emergence and developing interventions at the people-wildlife-environment interface – that is, incorporating an effective One Health approach in broader environmental management.

One Health in Australia: from the past to the future

Australia is a trading nation, and a federated country. In common with much of the world, Australia has historically taken a siloed approach in addressing future health threats. For example, over a decade ago the Australian Government invested heavily through a range of interventions to address the threat of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 virus. Concurrently, the World Health Organisation (WHO) was reporting that the world was moving closer to an influenza pandemic as “H5N1 avian influenza virus has met all prerequisites for the start of a pandemic except one: to spread efficiently and sustainably among humans.” In respect of this WHO view, Givney (Reference Givney2013) argued, “We would be in terrible straits if that disease (H5N1) became readily transmissible between people. That would be our next pandemic, and in fact it is the one that we are expecting.” Australian Government investment in the H5N1 threat at that time totalled approximately AUD623 million (ANAO, 2007), the lion’s share of which was invested in the public health portfolio, to build, inter alia, medical stockpiles of antiviral drugs and personal protective equipment. Less than 10% of this figure was invested in improving prevention and detection capacities where the pathogens with pandemic potential could be expected to emerge – in wild and domestic birds. Additionally, Australian government pandemic planning was approached agency by agency, jurisdiction by jurisdiction; albeit with stated links to one another but was not a systems-based approach.

Against that background, twenty years ago, Wildlife Health Australia was initially established as The Australian Wildlife Health Network and its vision: “A nationally integrated wildlife health system for Australia” and its mission: “To facilitate collaborative links in the investigation of wildlife health to support Australia’s trade, human health and biodiversity” reflected the drivers and pressures of the time. In other words, it was established as a national body with links to Australia’s governmental biosecurity and wildlife management systems (Woods and Grillo, Reference Woods, Grillo, Vogelnest and Portas2019). The activities of the organisation focussed on how wildlife disease impacted trade and market access for Australian agricultural producers and the need for further focus and integration of wildlife health information into Australia’s national animal health surveillance arrangements.

Formation of the organisation was driven by the emergence of several new and emerging diseases diagnosed in Australia’s wildlife in the mid-1990’s, including Hendra virus and Australian Bat Lyssavirus (Bunn and Woods, Reference Bunn and Woods2005). An internal review and consideration of Australia’s animal health preparedness, following the 2021 foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom, suggested that Australia could further improve its already impressive biosecurity arrangements by more focus on wildlife. Additionally, the changing requirements of the then Office International des Epizooties, now World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), to replace “Absence of Evidence” with “Evidence of Absence,” as part of surveillance requirements for proof of freedom to secure preferred trading partner status for animal products, became important decisions in health, trade, and environment policies – but remained not well coordinated.

Since the establishment of Wildlife Health Australia, the global and national policy landscapes have changed and now recognise the need for greater integration of biosecurity activities across animal, human and environmental sectors. Craik et al. (Reference Craik, Palmer and Sheldrake2017) identified priorities for Australia’s biosecurity system, including a need for a One Health approach and an increased focus on health-environment links. Yet, as noted earlier, One Health is still too much focussed on human health. Wildlife Health Australia has responded to this challenge by becoming a key national integrating structure linking human, wildlife, livestock, and ecosystem health in the context of a deteriorating biosphere – going some way to respond to questions and concerns raised by Stephen (Reference Stephen2023).

In recent times, Wildlife Health Australia has increasingly focused on the feedback loops between wildlife health, livestock health, human health, and the “health” of ecosystems with a current vision: “Healthy wildlife, healthy Australia” and mission: “To lead national action on wildlife health to protect and enhance the natural environment, biodiversity, economy and animal and human health through strong partnerships.” In implementing this mission and striving for that vision, Wildlife Health Australia has grown from a primarily veterinarian-based organisation focussing on diseases with part of their ecology that may impact on trade and market access, to an organisation working across biosecurity to environment, including a focus on the effects of increasingly severe weather and climate events (droughts, floods, and wildfires) on wildlife. Wildlife Health Australia works with all Australian governments (Federal, state, and local), as well as with community and non-government stakeholders. It has become thus a key national integrating structure linking human, wildlife, livestock, and ecosystem health in the context of a deteriorating biosphere.

Over forty-five partner agencies and organisations now form the basis of Australia’s wildlife health surveillance system, which includes agriculture and environment agencies of national, state, and territory governments, zoos, private veterinary hospitals, and universities. This surveillance system captures information relevant to animal, human and environmental health. Several targeted national programmes are also in place supporting human health, Industry, and biodiversity, including a Bat Health Focus Group, the National Avian Influenza Wild Bird Surveillance Program (Wildlife Health Australia, 2023a), and a national Koala Disease Risk Analysis (Vitali et al., Reference Vitali, Reiss, Jakob-Hoff, Stephenson, Holz and Higgins2023). A range of biosecurity, health, and environment professionals are included in all Wildlife Health Australia programmes providing strong connection across and between sectors. In addition, where needed, Wildlife Health Australia brings in economists, policy and legal advisors, social scientists, and other disciplines alongside veterinarians and wildlife professionals, to assist with project design and or implementation.

Wildlife Health Australia: One Health, and planetary health

Increased recognition of One Health as an integrating vehicle has also been emphasised in The Lancet Rockefeller Commission on Planetary Health (The Lancet, 2015). Planetary health attempts to set human health within the state of the biosphere on which human health depends. This also means considering values around justice, equity, and sustainability. As the One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP, 2023) note “…implementing One Health requires transdisciplinary approaches, with a systemic focus on the health of animals, people, and ecosystems worldwide, and potential solutions that are equitable, inclusive, and sustainable.” Such recognition of the role of non-government stakeholders, the use of a partnership-type approach, and founding principles and values that emphasise the need for respect and inclusivity, is a strength of Wildlife Health Australia (Woods et al., Reference Woods, Reiss, Cox-Witton, Grillo and Peters2019).

In 2020, Wildlife Health Australia developed WildPLAN, a strategic vision for wildlife health in Australia (Wildlife Health Australia, 2023b). In bringing together civil society, government, non-government, and the private sector, working across disciplines and developing First Nations partnerships, Wildlife Health Australia facilitates improved collaboration and information flow. The Impact of WildPLAN is achieved through focussing on national needs, delivered locally with Wildlife Health Australia’s greatest strength being its ability to engage a large and varied group of stakeholders, many of whom may have valuable information, expertise, and experience with wildlife health issues, and giving them a One Health context (Wildlife Health Australia, 2023c).

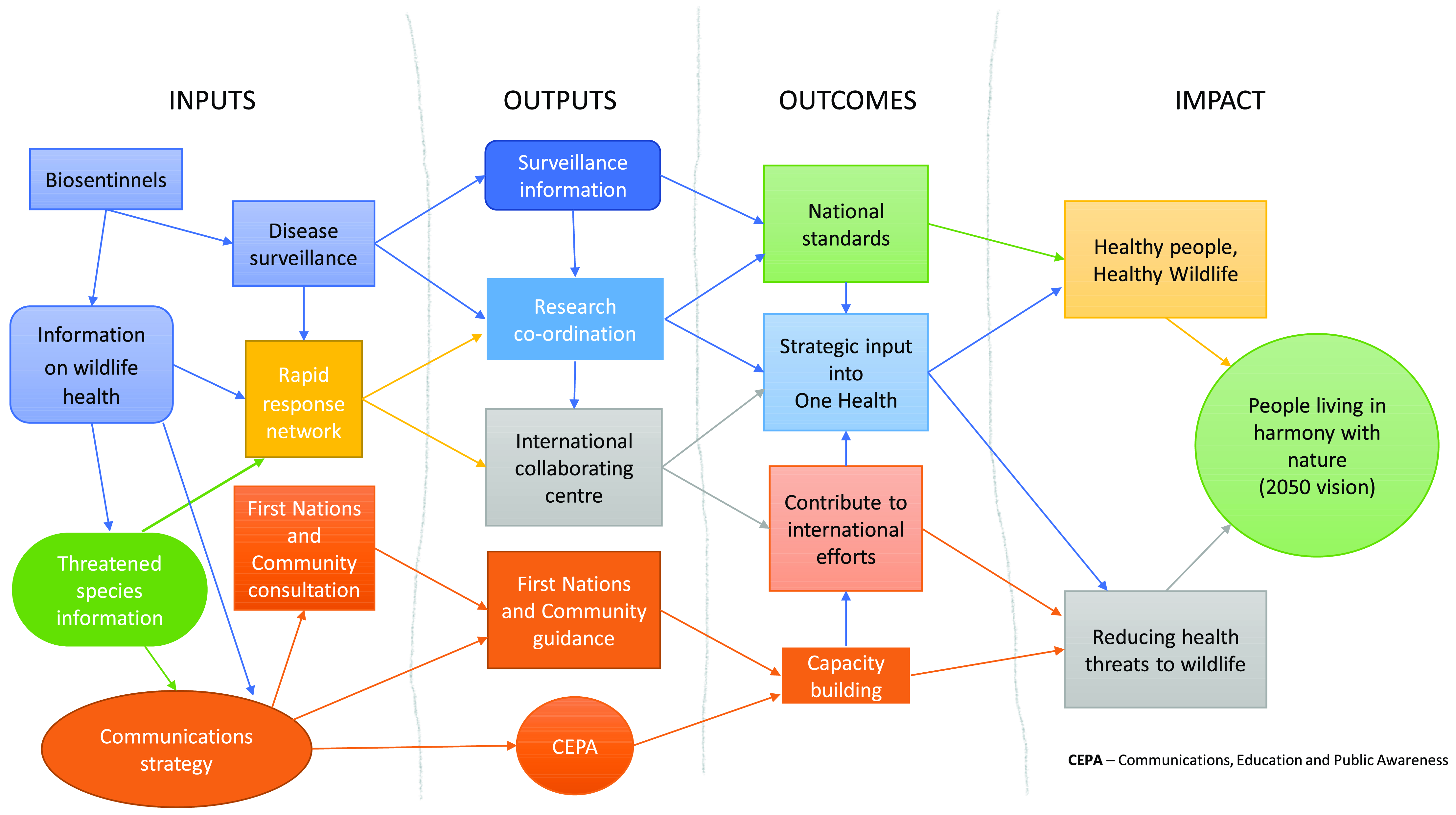

In seeking to work within the One Health ambit, Wildlife Health Australia has moved from a focus of wildlife health surveillance for diseases that may impact on trade and market access, to actively incorporating understanding of health and disease issues that may impact on the rest of biodiversity, including people. This has resulted in a broad suite of activities relevant to One Health. To undertake this range of activities, Wildlife Health Australia has developed a Theory of Change (Figure 1) to monitor its pathway to impact.

Figure 1. The Wildlife Health Australia Theory of Change.

This Theory of Change has a desired impact that echoes the vision of “People living in harmony with nature,” as described in the Kunming-Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD, 2022). The Framework embraces a One Health approach to guide global actions, delivered locally, to “conserve, sustainably use and equitably share biodiversity.” FAO, UNEP, WHO and WOAH (2022) has a Theory of Change impact as “A world better able to prevent, predict, detect and respond to health threats and improve the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment while contributing to sustainable development.” By selecting “People living in harmony with nature” as its target Impact, Wildlife Health Australia has also moved beyond the One Health Joint Plan of Action (FAO, UNEP, WHO and WOAH, 2022) Theory of Change and tied its Theory of Change to global biodiversity and sustainability aspirations.

In undergoing this process of change to embrace broader environmental aspirations, Wildlife Health Australia has developed “WILDDeST,” a decision support tool designed as part of structured, standardised, and transparent decision-making process for wildlife health incidents (Wildlife Health Australia, 2023d). WILDDeST assists government agencies in initiating investigation of wildlife health incidents, decision-making for ongoing wildlife health incident investigation or management and identifying the lead agency with required technical expertise for each incident. Decision support tools have been shown to provide additional insight and clarity to the decision-making process (Hemming et al., Reference Hemming, Camaclang, Adams, Burgman, Carbeck, Carwardine, Chadès, Chalifour, Converse, Davidson, Garrard, Finn, Fleri, Huard, Mayfield, Madden, Naujokaitis‐Lewis, Possingham, Rumpff, Runge, Stewart, Tulloch, Walshe and Martin2022), something especially important in navigating the complexity of decision-making under a One Health framework.

Perhaps most importantly, recognising the need to play a role in regional and global wildlife management, the Australian government has supported Wildlife Health Australia becoming an International Collaborating Centre on Wildlife Health and Risk Management for the Indo-Pacific. This Centre focuses on drivers of disease emergence, operates to the One Health principles of capacity building, coordination, collaboration, communication, and supports the World Organisation for Animal Health Wildlife Health Framework objective of “Protecting wildlife health to achieve One Health” (World Organisation for Animal Health, 2023). In collaboration with the IUCN Conservation Planning Specialist Group, an education and training component is also being delivered as a wildlife disease risk analysis course based on One Health principles, with workshops in applied One Health practice as part of the development of integrated regional wildlife health networks (Conservation Planning Specialist Group, 2023).

As well as these structural changes, a highly significant “One Health Surveillance Program” has also been initiated by the Australian government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. This programme is administered by Wildlife Health Australia as part of Australia’s national biosecurity arrangements and provides funding and support to investigations of wildlife health issues and events occurring in Australia that may be relevant to One Health, crossing and breaking down the boundaries between animal, human and environmental health.

Conclusions and perspectives: how Wildlife Health Australia makes/will make an impact

The global move towards One Health implementation that positions animal, plant and ecosystem health as mutual beneficiaries from our investments and interventions, must be supported by foundational organisational change. The Theory of Change that supports the vision and mission for Wildlife Health Australia, is based on its strategic vision and will focus on the impact achieved by Wildlife Health Australia, using the measures for monitoring and evaluation described in WildPLAN (Wildlife Health Australia, 2023b). Tying the Wildlife Health Australia Theory of Change directly to the vision of the Kunming-Montréal Global Biodiversity Framework is both a logical extension and a strategic decision on the part of Wildlife Health Australia. It situates Wildlife Health Australia as a key part of Australia’s international biodiversity commitments, alongside its biosecurity commitments, and allows for delivery of a One Health approach embracing people and the rest of Australia’s biodiversity.

In answering the question of “How must One Health policies and practice change to make animal, plant and ecosystem health a primary focus that is influenced by human and environmental factors?” Wildlife Health Australia sees One Health as a vision for biodiversity in a future that embraces and supports the ultimate objective of “People living in harmony with the rest of nature.” This approach taken by Australia (as a federal country) is an example of how One Health can be operationalised at a national scale to move the idea from people as primary beneficiaries of One Health to an approach where the health of people, wild and domestic animals, plants, and the biosphere, are linked and are mutual beneficiaries.

Data availability statement

All data used for this project were extracted from literature sources cited in the reference section of this paper, or from Data available through www.wildlifehealthaustralia.com.au

Author contribution

The concept was agreed by all authors, PB and RW created a first draft, all authors then contributed to adding to and editing the final submitted version.

Financial support

Core funding for Wildlife Health Australia is provided through a cost-shared agreement with the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry and all Australian state and territory governments via Australia’s National Biosecurity Committee. Significant in-kind funding and support is also provided by Australia’s states and territories, zoos, universities, and other veterinary practises that treat wildlife, as well as many other supporters and collaborators both within and outside of government in Australia.

Competing interests

The authors attest they have no conflicts of Interest.

Comments

No accompanying comment.