Introduction

Over the course of the twentieth century, a multilayered framework of interventionary practices, international law, multilateral institutions, donors, and civil societyFootnote 1 had emerged to support peace processes, peacemaking tools, and local peace activism. This ‘international peace architecture’ (IPA) brought together older conflict management methods such as diplomacy and the balance of power, with the liberal international framework of the twentieth century, the demands for rights and development from anti-colonial movements, liberal peacebuilding, a further expansion of rights beyond basic forms after the 1980s, and statebuilding. This process was closely related to the agency of an emerging global civil society.

The IPA had recently also been confronted with a growing critique of liberal peacebuilding:Footnote 2 weak civil society networks became overloaded with responsibilities to reform conflict-affected states, while international support for peace processes tended to be limited and fluid. As a consequence, international peace interventions often produced frozen or stalemated peace processes. Many peace processes have stagnated, regressed, or faltered over the last thirty years as the cases of Cyprus, Israel/Palestine, Libya, Yemen, Sierra Leone, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, El Salvador, Colombia, Sudan, Lebanon, the Sahel region, Afghanistan, and the Balkans demonstrate.

The contours of an IPA have emerged to overcome the different dimensions of violent conflict. Multilateral and intergovernmental organisations have combined efforts with transnational and domestic actors to end wars. As a result of this collaboration a toolbox of interventionary practices has evolved over time, including peacekeeping, mediation, development, democratisation, peacebuilding, and statebuilding. Despite much concerted effort on behalf of diplomats, the UN, NATO, international courts, regional actors (such as the European Union and the African Union), donors, foreign policy, and NGO/INGO personnel, current peace processes have often failed to preserve peace and security, or to promote justice, rights, and development in many conflict-affected societies. There have been few success stories, and most cases are ambiguous at best.Footnote 3 The IPA represents an awkward and unstable synthesis of state power, interests, pragmatism, and internationalism along with science, transnational ethics, and transversal emancipatory claims. In practice, illiberal, and authoritarian outcomes are not unusual (as in Guatemala, Cambodia, El Salvador, or Afghanistan).Footnote 4 In some cases, peace processes have become more important than a settlement (for example, Cyprus),Footnote 5 or almost as loathed as open conflict (for example, Palestine and Colombia), while reform processes have been halted or reversed (for example, Bosnia, Tunisia, Libya).Footnote 6 Conflicts and violence are on the rise around the world with grave human, political, economic, and global consequences.Footnote 7 Many have been subject to lengthy and often unsuccessful attempts to make peace.

Across different regions, the inability of domestic actors to resolve disputes peacefully and the failure of external interventions necessitates a rethinking of existing policy and epistemic approaches to peace.Footnote 8 There is no longer a widely agreed formula for social relations, reform, peace agreements, form of state and economy, or regional and international arrangements in which ‘peace’ should be nested. The liberal-international order of the twentieth century has become ineffective, if not moribund. Peacekeeping, peacebuilding, and peacemaking have been blocked, undermining the legitimacy and capacity of the wider IPA and nothing new has emerged to replace them.

The IPA is riven with uncertain compromises and has itself become compromised. Some of its elements contradict each other and provide opportunities for systematic blockages of peace processes as this article demonstrates: Top-down statebuilding and peacebuilding interventions in ethnically divided societies have resulted in elite peace capture which exploits power-sharing arrangements to obstruct reconciliation.Footnote 9 Elites’ or identity groups’ control of state institutions and resources has survived the attempts of peace processes, social and revolutionary movements to redistribute.Footnote 10 Hence, civil society struggles with these (externally supported) power structures, everyday nationalism within and outside institutional settings, unresolved legacies of the conflict, and with socioeconomic impoverishment reinforced by post-2000s neoliberal statebuilding. The failure of international statebuilding to respond to local culture, needs, and interests, as well as questions related to global justice, has empowered unstable neoliberal, criminalised power structures, and warlords.Footnote 11 This undermines conciliatory forms of peace, and has given rise to even more narrowly based ‘stabilisation’ approaches.Footnote 12 In this process, rights and material gains that should be associated with peace and reform, especially from an ethical and scientific basis, have been undermined. Meanwhile the networked, scalar, and mobile elements of a ‘digital’ shift in international relations has been ignored, especially where it countermands rights and global civil society campaigns and supports authoritarian forms of power.

Through this critical lens ,Footnote 13 counter-processes and peace-breaking dynamics have perhaps become more of a plausible ‘process’ than any peace process itself.Footnote 14 Indeed, the latter looks epistemologically naïve. Inadvertently, this may reflect long-standing debates about the dynamics of counter-revolution.Footnote 15 Yet, contemporary revolutionary agency has fared even worse than peace agency: despite its sophisticated understandings of justice, legitimacy and reconciliation, it has not overcome the counter-revolutionary processes that are connected to the state as well as across scales.Footnote 16 As a broader dynamic these counter-processes represent reactions against ‘progress’ in ethical and scientific understandings of peacemaking, and enable a winding back of reformist, revolutionary, and internationalised versions of peace, democratisation, human rights, and the rule of law. They rest on justifications for elite power, geopolitics, nationalism, stratification, and inequality, as well as on the state's deployment of violence. Hence, this article aims to shift the academic focus away from the shortcomings of peace processes to shed light on their polar opposites: blockages and counter-peace processes at the international, national elite, and societal level.

We argue that distinct patterns are emerging in the blockage of peace and reform processes. We aim to identify, how reactionary processes operate to challenge peace praxis in order to preserve power, stratification, hostile identity framings, and economic privileges. Furthermore, we analyse how peace interventions have become entangled with counter-peace processes. Which factors consolidate or deteriorate emerging conflict patterns? Are blockages to peace systemic enough to construct a sedimentary and layered counter-peace edifice? This study introduces the concept of counter-peace as a tool to critically interrogate a potentially systemic array of blockages to peace, juxtaposing peace processes with counter-revolutionary theory. This may help to understand why so many peace processes and peacebuilding missions appear to have led to illiberal and authoritarian outcomes. Counter-peace processes may display a similar relationship to peace processes as counter-revolution does to revolutions. The article evaluates whether the blockages add up to a more sophisticated counter-peace edifice than previously understood. Its constituent parts, tactics, strategies, combined with structural obstacles and unintended concequences of flawed peace processes may well add up to an overall counter-peace architecture, which shapes the international system itself, just as a counter-revolution depends on and occupies the state.

As a first step, this article outlines the concept of the counter-peace and distinguishes it from related concepts. A subsequent section elaborates three categories of its empirical manifestation and develops a model of how these categories may be linked. They are informed by a number of reports commissioned by the authors in partnership with local scholars and civil society organisations in a range of cases, as well as by the wider, secondary, empirical literature.Footnote 17 A conclusion elaborates whether, based on the paper's findings, the assumption of systemic connections between blockages to peace can be upheld.

Locating the counter-peace

This section distinguishes the counter-peace from other concepts before drawing on the literature on counter-revolutions to see what analysis of blocked peace processes can learn from it. At first glance, Johan Galtung's negative peace might appear to be a similar concept since some empirical manifestations of counter-peace processes are also characterised by a combination of surface stability and underlying violence. Both negative peace and counter-peace try to analyse why peace processes are often unstable. Yet the two concepts rest on divergent assumptions and drive towards different epistemologies: Galtung's negative peace explores different types of violence that had escaped our understanding of peace, especially structural and cultural violence.Footnote 18 However, his concept essentially follows a ‘curative rationality’, which prescribes ‘a road from war to positive peace’.Footnote 19 Hence, Galtung examines connections between different actors’ needs and ideals with the aim of moving our understanding of peace from a confrontation of unbridgeable differences (in which the realisation of one peace vision only occurs at the expense of other actor's aspirations) to one of interconnectedness. Counter-peace, by contrast, is a diagnostic tool to explore the links between systemic challenges to peace. Here, the assumption is that blockages to peace might be connected in ways that have hitherto been overlooked. Hence, it goes beyond negative peace by searching for patterns that connect different types of blockages to peace across different conflict spheres as well as cases.

This epistemological interest also goes beyond the literature on spoilers.Footnote 20 The spoiler debate provided a rich conceptualisation of peace spoiling actors, goals, tactics, and actions, but less on their connections across all scales. For instance, Stephen Stedman's typology of peace spoilers focuses mostly on the elite level, and touches only briefly on the role of global and regional actors. It does not examine transnational blockages to peace, nor local and grassroots counter-peace movements beyond organised politics.Footnote 21 Crucially, due to its focus on intentionality, the spoiler debate neglects structural factors, path dependencies, and unintended consequences.Footnote 22 These limitations have prevented a fuller assessment of the ways in which different blockages to peace are connected across conflict spheres and cases.

Scholarship in different theoretical and disciplinary fields has produced a large range of counter concepts, which usually position themselves towards power: Concepts such as counter-conduct,Footnote 23 counter-hegemony,Footnote 24 and counter-powerFootnote 25 challenge dominant forms of power, while counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, and counter-revolution aim to restore them. Concepts such as counter-law,Footnote 26 counter-rights,Footnote 27 and counter-justiceFootnote 28 denote actions to contain human rights and undermine democratic institutions. The most insightful analysis for this article among the various counter concepts is the literature on counter-revolutions though, since it analyses most clearly the ways in which actors try to erode, contain, or eliminate emancipatory agency. So what can we learn from the critical-historical concept of the counter-revolution for our understanding of counterpeace processes?

In their broader outline, counter-revolution and counter-peace are similar in that our understanding of both processes is derived from what they oppose: broad security, rights, justice, and equity as the hallmarks of a positive, hybrid, and everyday peaceFootnote 29 running parallel to the emancipatory objectives of freedom and equality in revolutions.Footnote 30 Accordingly, the most obvious tactics to thwart emancipatory movements involve mobilising coercive state institutions, media, and other influential social and political structures. However, counter-revolution and counter-peace both cover a spectrum of political responses to societal and international pressure for change, which expands well beyond oppression, restoration, and war. Instead, both processes are most effective, if they do not constitute the opposite of revolution and peace processes, but represent watered-down alternatives to them. They may maintain some of their benefits, such as basic security, while rejecting human rights or significant reform, for example. There is continuity in power structures in both, in other words. In order to avoid fundamental transformation, counter-revolutionary, or counter-peace elites may be forced to enact substantive reforms. The 1848 revolutions for instance, showed that even after the military defeat of revolutionary movements, counter-revolutionary governments might be compelled to enact fundamental political or social reforms if deep structural changes can no longer be postponed.Footnote 31 Yet in contrast to revolutionary transformations, counter-revolutionary reforms only bow to a limited set of demands for change in order to protect social or political hierarchies against deep transformation.Footnote 32

In contemporary peace processes, similar types of conflation occur. Peace agreements, for instance, may harbour within them the seeds of a counter-peace. While the Ta'if and Dayton Agreements stopped further bloodshed in Lebanon and Bosnia, respectively, they also constituted the institutional framework for peace capture. Former warlords turned into political powerholders, preserving ethnic or sectarian power structures. Like the Thermidor in revolutions, peace agreements’ initial success in ending violence soon gave way to exclusion, segregation, and marginalisation, pre-empting reconciliation and progressive forms of peace (as will be further analysed below).

Hence, revolution and counter-revolution – as much as positive peace and counter-peace – are dialectically related.Footnote 33 This understanding of the counter-revolution and counter-peace resonates with Michel Foucault's understanding of power. Of the various factors, which make up Foucault's notion of power, our concept of counter-peace investigates the multiplicity of dominant force relations and their institutional organisation; their mutual support and the ways in which they disconnect and marginalise the struggles to transform and reverse those force relations.Footnote 34

In their relationship with violence, counter-revolution and counter-peace cover a range of strategies. As long as revolutions were still characterised by terror, war, and vengeance to an extent that revolutions had been inconceivable ‘outside the domain of violence’,Footnote 35 counter-revolutions may have appealed to many as a form of moderation.Footnote 36 Indeed, counter-revolutionary alliances often regarded themselves as guardians of vertical as well as horizontal security.Footnote 37 However, in terms of their strategies of political contestation and their relationship to state power, revolutions have changed drastically over time. Due to the growth of social movements, armed takeovers of state power have been replaced by non-violent, leaderless, and non-ideological movements with little ambition to own the state.Footnote 38 In the face of these weaker forms of revolutionary contestation, counter-revolutions have been able to refine their own strategies. Coercion and oppression, for instance, can be combined with democratic legitimacy as the violent reign of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt has shown. External counter-revolutionary intervention operates through aid and diplomacy as much as through proxy wars and direct military intervention.

Equally, the counter-peace ranges from unmitigated forms (for example, wars, dictatorship and military occupation) to the more subtle forms of political stalemate (see next section). Counter-peace processes and counter-revolution both capture the institutions of the state in order to change the tactics of state formation processes.Footnote 39 Elites and their criminal networks can continue their state formation project without war by controlling state institutions. Corruption and state violence are used in this new phase of the counter-peace and counter-revolutionary process. Since foreign governments work with and through state structures, this state capture allows aid and the counter-processes to align themselves: Foreign aid that overdevelops the coercive power of the stateFootnote 40 may thus strengthen counter-peace forces. In contemporary non-violent revolutions, a similar process occurs, in which external support reinforces the oppressive and exclusionary structures of the state.Footnote 41

As in counter-revolutions, the alliances between domestic and international counter-peace actors and their ability to generate societal support is of crucial importance. Hence, our analysis takes inspiration from scholarship on counter-revolutions by looking into the ideological, socioeconomic, and political connections between populations and counter-peace elites. Ideologically, nationalism in counter-peace and traditionalism in counter-revolutions may forge cross-class alliances on similar grounds: ‘to reclaim an idealised but imperilled past and present’.Footnote 42 Yet, in counter-revolutions, divergent ideologies and material interests of the different classes have ultimately resulted in fragile alliances.Footnote 43 Hence, we will analyse whether the counter-peace shows a similar mix of ideological unity and disunity across its various actors.

In order to understand how the counter-peace can be overcome, we can draw on analysis of the defeat of counter-revolutionary alliances. The search for an institutional epicentre of a counter-peace process, for instance, may give us clues about its durability. In revolutions, the collapse of such core institutions has often heralded the fragmentation of the counter-revolution.Footnote 44 Whether a similar weakness can be detected in the counter-peace will be investigated in this analysis.

Empirical manifestations

In an attempt to illustrate and elaborate various forms of counter-peace, this section examines three different types of empirical manifestations, ranging from a ‘stalemate pattern’ to a ‘limited counter-peace’ and an ‘unmitigated counter-peace’. Since this article is conceptual, we explore patterns that characterise different types of conflicts. In this exploration, we draw on examples rather than presenting comprehensive case studies to illustrate these categories. While still not at the level of a fully developed case study, the Russia-Ukraine conflict will receive more attention in this article in order to show how conflicts can move across our three counter-peace patterns. Moreover, this conflict highlights the connection between revolutions and conflict and shows that our typology also extends to interstate wars. The presented categories are not exhaustive, but rather a starting point for our examination of how counter-peace is constituted. Drawing on the counter-revolution literature, we will look for the following: (1) an epicentre of the conflict system; (2) the possibility for a broad counter-peace alliance that includes large segments of the population as well as the backing of external actors; and (3) whether peace interventions have inadvertently contributed to the counter-peace process.

Stalemate pattern

This pattern is characterised by frozen conflict, in which violence has been circumscribed but intergroup tensions persist unabated. In the stalemate pattern civil society, international donors and the multilaterals form a weak alliance. The state has been integrated into a peace and development process and all parties and levels are somewhat interdependent. They are captured by a range of legal, political, economic, and geopolitical codependencies, which are finely balanced but block both progress as well as the collapse of the stalemate.

At the heart of this pattern lies a ‘formalised political unsettlement', through which a war has been ended, but which fails to resolve the radical disagreement between the conflict parties.Footnote 45 Such unsettlements have managed to end war either through the separation of former conflict parties by continuously contested borders (as in the territorial divisions in Cyprus, Kosovo, India/Pakistan) or through power-sharing agreements (as in BiH, Lebanon, Iraq, Northern Ireland, Burundi). While necessary to stop large-scale violence, ethnic segregation and power-sharing agreements have turned into blockages to reconciliation by reinforcing ethnic or sectarian divisions in society.Footnote 46 Rather than resolving the conflict, the formalised political unsettlement only translates the war into political institutions, which become deadlocked and thus it perpetuates the radical disagreement between the conflict parties.Footnote 47 While the conflict parties remain fully committed to their incompatible positions, the conflict appears ‘frozen’ as long as neither attempts resolution through accommodation, withdrawal, or military conquest. In the stalemate pattern, war is replaced by ‘non-violent war’ as an intense power struggle over the new state institutions ensues, in which the conflict parties maintain close alliances with violent forces.Footnote 48 This dynamic has implicated peacemaking in extended deadlocks (as in Cyprus since 1963,Footnote 49 or Bosnia since 1995),Footnote 50 and is perhaps now the norm. This also reflects the limitations of the relationship between peace, self-determination, and sovereignty at a practical level, as well as legacies of imperial history (many frozen peace processes emerged in former colonies and post-socialist states with acute development and economic problems).

In continuous disputes over territory, self-governance, sovereignty, rights, and entitlements, peace interventions supply conflict parties with valuable resources: time to reorganise, international legitimacy, alliances, material support, etc. Conflicts in the stalemate category are thus symptomatic of internationally sponsored peace settlements, protracted dependency on external aid and intervention. While this extensive involvement of the IPA might raise hopes for a strong role for civil society and a dynamic peace process, this is not the case. Indeed, the following analysis will identify the stalemate as a product of state capture by counter-peace elites, rendering civil society and international peace interventions unable to move the peace process forward.

Power-sharing agreements are supposed to ensure that the interests of all former conflict parties are represented in the political system. Competition between the conflict parties thus moves from the battlefield into the parliament. However, power-sharing institutions encourage mono-ethnic or sectarian political parties, which in turn reinforce identity-based voting patterns. The division of power along identity lines turns ‘ethnic entrepreneurs’ into gatekeepers of access to political influence.Footnote 51 This creates fiefdoms for former conflict actors and thus inscribes corruption, clientelism, and patronage into state institutions.Footnote 52 For example, in Kosovo, corruption among ministers from minority communities was tolerated to preserve the multi-ethnic composition of Kosovo's institutions.Footnote 53 As a result, the state remains weak and internally divided.

Since neoliberalism widens the gap between the beneficiaries of patronage and corruption and the impoverished rest of the population, the political economy of sectarianism or ethno-nationalism fosters political instability.Footnote 54 Contributing to the frequency of political crises in power-sharing polities is their veto-mechanism, which discourages compromise and stable cross-identity alliances.Footnote 55 It allows some groups to block the advancement of the rights of others, while asserting their exclusive political and security agendas. In the resulting antagonistic political frameworks, parties have no incentive to reach out, bridge differences and promote reconciliation. Thus, power-sharing arrangements have allowed (ethno-)nationalist elites to co-opt the peace process and inscribe counter-peace processes into state institutions, while subterranean movements militarise the public sphere. As Lebanon's various political crises show, power sharing does not imply responsibility-sharing between former warlords.

Between 2014 and 2015, a series of peace negotiations sought to transform Ukraine's conflict in the Donbas from war into a political stalemate. The conflict emerged after the elected President Viktor Yanukovych was toppled by the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. Initially peaceful counter-protests in the South and East of Ukraine against the Westward orientation of the new government were militarised by Russia's infiltration of the Donbas through militants, taking over government buildings and expanding their occupation through warfare.Footnote 56 In order to de-escalate the conflict, the pro-European national government and the pro-Russian secessionist leaders in Donetsk and Luhansk agreed to share power through decentralisation as laid down in the Minsk I and II agreements. However, since neither side implemented their obligations to demobilise their troops, the conflict never settled into the stalemate pattern.

Alternatively, stalemates occur if wars are ended through the establishment of continuously contested borders and ethnic segregation as in Kashmir, Cyprus, and Kosovo. Newly erected borders may terminate hostilities, but freeze rather than resolve the underlying conflict. Border infrastructure formalises a political disagreement between the conflict parties if land claims on both sides continue to contest the territorial integrity of the new entities. In such contexts, uneven international recognition and external geopolitical interventions distort the political playing field between the conflict actors in a way that makes a peace agreement unlikely. Indeed, the conflict party whose sovereignty is recognised might have little incentive to compromise.Footnote 57

Geopolitical meddling in stalemates tends to distort conflict dynamics and reduce the possibility of conflict resolution (as frequently occurred during the Cold War). It might even facilitate a descent into new wars as Russia's role in the escalation of conflict in Ukraine demonstrates. After the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, a conflict emerged on different levels:Footnote 58 between the Euromaidan and anti-Maidan protesters; between local elites in the south/east of Ukraine; between local elites and the new revolutionary government in Kyiv and between Russia and Ukraine. Yet, Russia's interventions dominated the conflict dynamics. The Kremlin replaced local elites in the Donbas region with pro-Russian militants, conducted covert and overt military interventions and bankrolled the military destabilisation of Ukrainian society. This meddling generated an important shift in the underlying power dynamics. It allowed the Russian-supported militants to establish an unrecognised border between the secessionist oblasts and the rest of the country. Despite the opposition of the majority of local residents to the Russian-led takeover of the local government in the spring of 2014,Footnote 59 Russia's strategy of escalating hybrid warfare, creeping occupation and ever-expanding political demands effectively partitioned Ukraine within a year.Footnote 60 Yet, in contrast to stalemate contexts such as Cyprus or Kosovo, the erection of border infrastructure, policing and military enforcement only limited the battlefield rather than producing a stalemate. Since Russian President Putin's larger political ambitions of establishing a ‘New Russia’ were thwarted by continued Ukrainian resistance, he settled for a territorially confined conflict in the Donbas between 2014 and February 2022. Due to Russia's meddling, Ukraine slid into a limited counter-peace pattern.

Once the formalisation of unsettlement in stalemate contexts happens, it becomes persistent.Footnote 61 Further peace interventions in frozen conflicts often fail to advance the process beyond stabilisation. For instance, while the Dayton Peace Accords envisaged the return of internally displaced people to their homes, hidden strategies of ethnic cleansing have allowed ethno-nationalist actors to create mono-ethnic spaces as a major blockage to peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina.Footnote 62 This territorial consolidation of ethnicity has supported the rise of extreme nationalist parties, which further obstruct inter-ethnic reconciliation.Footnote 63 The EU's efforts to effect changes in the nature of the Bosnian state in the accession process and through the European Court of Justice have so far been resisted by the elites who benefit from the stalemate. In other cases (for example, Cyprus and Lebanon), the UN's long-term commitment to peacekeeping might have helped to prevent a relapse into war. Simultaneous mediation attempts to resolve the conflict in Cyprus, however, have remained blocked by ‘devious objectives’ on both sides since 1964, entangling the UN and EU as well as providing a platform for destabilising forms of regional geopolitics.Footnote 64

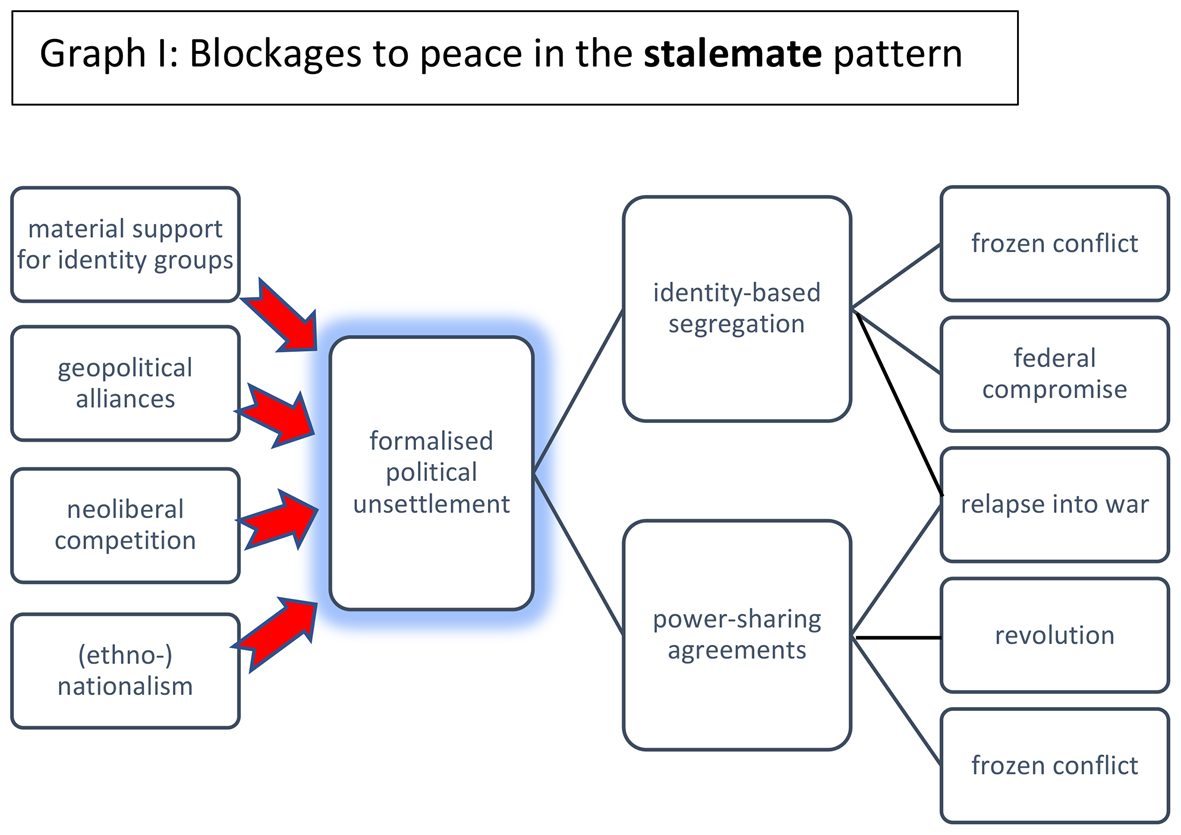

As shown in Figure 1, the last blockage to peace is constituted by ethno-nationalism or sectarianism. While both types of stalemate situations (power-sharing agreements and ethnic segregation) have generated different responses from their populations, both enable counter-peace alliances between the elites and the masses through identity politics. In segregated conflict contexts, popular support for a formalised political unsettlement can be secured as long as nationalism or sectarianism constitutes a cultural hegemony.Footnote 65 In such cases, dissent against the political stalemate only emerges in micro-political initiatives of peace formation, which have not been able to constitute a counterweight to powerful alliances or to undermine mass support for counter-peace elites.Footnote 66 Hence, civil society demands to include economic, cultural, and social rights in any peace process (as well as gender, reconciliation, justice, and restitution) tend to be easily diverted by counter-peace alliances.

Figure 1. Blockages to peace in the stalemate pattern.

In consociational democracies, alliances between counter-peace elites and large shares of the population are volatile due to the crisis-prone nature of the polities and their failure to satisfy the needs of the population. Indeed, beneath the surface, there might even be revolutionary fervour fermenting within societies affected by power-sharing agreements.Footnote 67 In Bosnia (in 2014) and Lebanon (in 2019), masses mobilised against power-sharing agreements that allowed sectarian actors to capture the state and camouflage exclusionary practices of corruption and nepotism while preserving sectarian interests. Yet protests died down before reaching a transformational outcome. With the trauma of recent war still fresh in the collective memory of a society, large swathes of conflict-affected societies might opt for stability over the liminality of a revolutionary situation. Hence, in this type of case, it is not ideologically driven support for counter-peace elites but fear of instability that might keep the formalised political unsettlement in place.

Limited counter-peace pattern

This pattern is characterised by surface stability in some parts of the country, punctured by pockets of warfare and parallel institutions. This pattern is common in the global south, as well as in conflict-affected postsocialist environments where deep developmental, justice, and ideological differences remained unresolved (often because of Western involvement rather than despite it). In some of these contexts, incomplete peace agreements have ended wars in the past but fell short of including all regions or conflict actors. Political and economic marginalisation has fuelled localised insurgencies and organised crime. Hence, the state formation process remains violently contested by non-state or parastate actors, who destabilise or govern parts of the country. In Africa, a growing number of more fragmented conflicts pries away peripheral areas from government control rather than aiming to seize the state through civil war.Footnote 68 In Latin America, criminal governance structures the lives of tens of millions of people in urban centres.Footnote 69 While resource extraction, racketeering and war economies keep conflicts going, environmental degradation sparks new ones. As a consequence, countries may simultaneously become the site of different types of conflicts (for example, the co-existence of secessionist conflict, insurgency, and violent localised land disputes in Nigeria and Mali).

In the limited counter-peace pattern, conflicts only affect pockets of a country or are sporadic. Economic liberalisation has turned the state into a vehicle for corruption and patronage,Footnote 70 while civil society is marginalised in the face of insurgency or criminal gang rule. These dynamics are connected to international security alliances rather than the rights framework of the international community, configuring the pattern for limited counter-peace.

At the heart of the continuous conflict in this group lie the deficiencies of the quasi-state.Footnote 71 Imposed by empires or imported by anti-colonial movements, the nation-state model was an alien structure in most societies in the Global South.Footnote 72 Postcolonial leaders adopted the model as a radical form of modernisation, which promised to advance their emancipatory objectives through the rationale of citizenship. Yet inheriting borders drawn by colonial administrators burdened postcolonial governments with the need to reconcile cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity beyond the capacity of the nation-state model. Integrating customary authorities into the modern state posed an irresolvable dilemma since law and rights as the tools of modernisation were bound to negate the hierarchical and exclusionary traditional institutions that they encountered.Footnote 73 Neo-patrimonial regimes emerged, which personalised power and shifted the state's modus operandi further away from the public good.Footnote 74

Many postcolonial states were saddled with indefensible borders, dependent development, and continued extractivism, narrowing their possibilities to provide security and development countrywide. The Structural Adjustment Policies of the 1980s further reduced the quasi-state's emancipatory promise. Liberalisation created patronage networks, aggravated corruption, and increased inequalities, while cutting vital state services for the masses. To populations living outside the reach of public infrastructure, the state appeared as an exclusionary project that failed to ensure security, welfare, and opportunities. This absence of state investment in education, health, security, and development especially in rural areas allows militias to offer otherwise absent economic opportunities such as income, bargaining power, and control of resources.Footnote 75 The resulting continuous conflict in peripheral areas thus turned the postcolonial state's aspiration of a monopoly of legitimate violence as well as shared security and development into a pipe dream.

Given these emancipatory impossibilities, statehood in the postcolony often remained incomplete. The international community appeared disinterested and distant. Insurgencies and organised crime have been feeding off the resulting frustrations of the populations in those ungoverned spaces. Combined with the effects of women's systematic subjugation in patriarchal societies, counter-peace forces find fertile breeding ground:Footnote 76 Femicides, the commodification of women through brideprices, and polygamy have created belligerent male surplus populations. With brideprices being a prevalent custom in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, brideprice inflation combined with misogyny have brought about organised violence and aided the recruitment of extremist insurgencies.Footnote 77 Patrilineal organisations such as clans and tribes tend to subjugate not only their own women, but also ‘feminise’ other groups. This leads to protracted conflicts between kinship groups, locked in a continuous fight for dominance.Footnote 78

Despite their emergence from different historical pathways, post-Soviet states may share many attributes of the quasi-state after their transition from imperial subjects to independent states. Ukraine, for instance, is also characterised by political and economic dislocation, insecurity, institutional weakness, historically rooted internal divisions and has been plagued by systemic social, political, and economic crises.Footnote 79 Moreover, like the postcolonial countries that gained their independence in the first half of the twentieth century, the post-Soviet states had freed themselves from imperial domination.Footnote 80 Under such conditions, sovereignty may be contested internally and externally. Inside Ukraine, a minority rejected the country's Western orientation after the Revolution of Dignity, while Ukraine's former imperial master fuelled and militarised these tensions through external intervention.

Peace processes further contributed to the displacement of the state by levelling the playing field between insurgents and governments in mediation processes.Footnote 81 The predicament of the Ukrainian government in the peace negotiations between 2014 and 2015 illustrates this dilemma: Unprepared for the Kremlin's strategy of hybrid warfare,Footnote 82 the Ukrainian government had to surrender authority to rebel leaders in Donetsk and Luhansk – despite questioning their local legitimacy – in order to prevent a further expansion of the war. Seeing the rebel leaders mainly as tools of Russian control, Minsk I and II have thus been described as ‘the capitulation of Ukraine before Russia’.Footnote 83

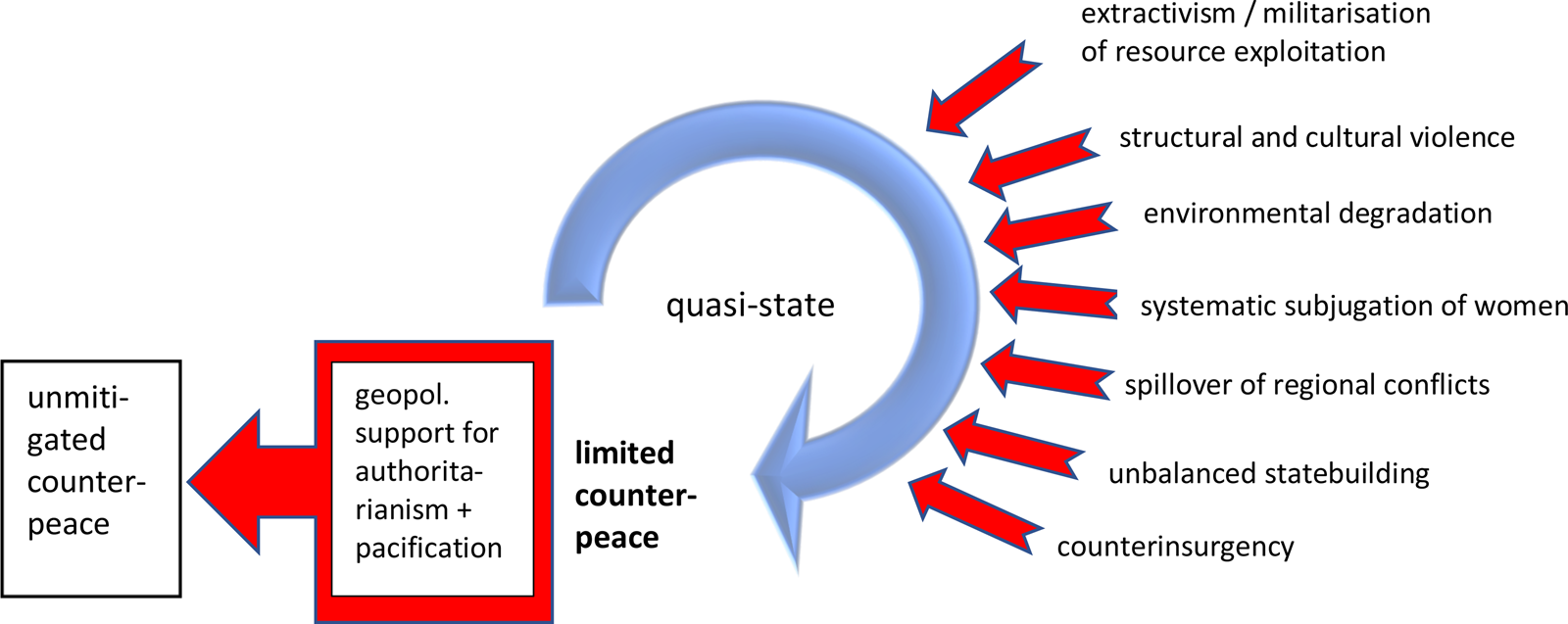

Persistent conflict tends to support the authoritarian tendencies of political elites. In such cases, it depends on the response of external and domestic forces, whether those tendencies are corrected or reinforced. If allies or peace processes support the increasingly repressive and exclusionary behaviours of quasi-state governments, the latter might turn into fierce states and slip into the unmitigated counter-peace category (see Figure 2). This often happens if external actors prioritise regional stabilisation over democratisation. Statebuilding can reinforce authoritarian tendencies, if its financial and military support reduces the willingness of a central government to make concessions towards internal dissent and provides the capacity for repression.Footnote 84 Indeed, UN peacebuilding missions in places such as Burundi, Angola, the DRC, and Mozambique have abetted oppressive behaviour of governments to retain access to political elites or uphold the image of an effective peace process.Footnote 85 By contrast, if external governments make support for quasi-states conditional on democratic reforms and human rights standards, this slippage into the unmitigated counter-peace category can perhaps be avoided, but this solution also raises the problem of enforcement.

Figure 2. From limited peace to unmitigated counter-peace.

The global war on terror has additionally fuelled many quasi-states’ transitions into fierce states. Counter-insurgency has been mainstreamed into development aid, combined with peacebuilding and resulted in the erosion of rights ambitions in development and statebuilding interventions. With its focus on capacity-building in security institutions and its neglect of the root causes of conflict, counter-insurgency mirrors the failures of international statebuilding.Footnote 86 Yet ‘pragmatic counter-insurgency’ diverges from the centralising approach of statebuilding by enlisting local strongmen and reinforcing their militias and police. This fosters the fragmentation of the quasi-state into mini-statelets.Footnote 87

Cooperation with militias is a risky strategy as well. It can deliver a justification for the external escalation of conflict from the limited counter-peace to the unmitigated counter-peace pattern. The Ukrainian case is insightful here: In the face of the much larger Russian military infiltrating the Donbas, the Ukrainian government enlisted nationalist paramilitaries to halt the expansion of the separatists. This in turn opened the government up to justified critique as well as Kremlin propaganda. Human rights watchdogs criticised the Ukrainian government for cooperating with militias that committed widespread human rights violations.Footnote 88 Worse still, the Kremlin used the Ukrainian government's connections with neo-Nazi paramilitaries such as the Azov Battalion as a justification for Russia's war on Ukraine in 2022, declared a ‘special military operation’ to root out ‘fascists’. While this propaganda did not manage to discredit the Ukrainian government in the eyes of its Western supporters, it may legitimise the Russian invasion in the eyes of many Russian state-media consumers.Footnote 89

Counter-insurgency and governments’ dependency on paramilitaries run counter to the original intention of statebuilding, which aimed to improve the quality of state institutions by refocusing the state's security apparatus on accountability and human rights. In practice, however, more ambitious targets for statebuilding raise issues of scale and affordability. In order to expand the infrastructural capacity of the quasi-state, enormous investment would be required. In the absence of adequate funding, peacebuilding and statebuilding missions have often been diverted towards achievable and measurable outcomes, related to stabilisation objectives.Footnote 90 Such interventions often end up serving external interests more than the conflict context. EU-financed crisis interventions in Europe's extended neighbourhood, for instance, have constituted little more than efforts to establish policing and border infrastructure aimed at the EU's fight against illegal immigration. If statebuilding fails to develop quasi-states’ service infrastructure, it cannot enable the polity to ‘work with and through other centres of power in society’.Footnote 91 On the contrary, the combined militarisation of the state through stability-focused statebuilding and counter-insurgency has further eroded the legitimacy of the quasi-state in the eyes of conflict-affected populations.Footnote 92 Economic marginalisation and treatment as ‘collateral’ by the military as well as externally sponsored ‘stabilisation operations’ facilitate the recruitment of conflict-affected populations into insurgencies in areas of limited statehood.

In Latin America, the predominant type of limited counter-peace is constituted by gang warfare in areas abandoned by the state. Here, the takeover of slum areas by criminal gangs poses a paradox that the quasi-state has not been able to resolve: On the one hand, criminal gangs’ violent struggle against a militarised police, other cartels as well as informants has made parts of Latin America and the Caribbean insecure.Footnote 93 On the other hand, criminal gangs have established a limited form of order in the slum areas under their control.Footnote 94 State policing, by contrast, tends to contain slums from the outside rather than providing security to their inhabitants. Hence, despite counterproductive crackdowns of the quasi-state on criminal gangs, the former also exists in a symbiotic relationship with the latter.Footnote 95

Through a counter-peace lens, slum dwellers like populations in insurgency-affected areas face a duopoly of violence since both militarised quasi-state and criminal gangs systematically violate populations’ human rights, while also providing some degree of stability. However, both counter-peace forces ultimately block positive peace. In contrast to the stalemate pattern, popular support for counter-peace forces in contexts that span insurgency, state, and criminal violence, is largely a matter of self-preservation. Suffering from structural violence, inhabitants of informal neighbourhoods, slum areas, and conflict-affected pockets of the country may collaborate with counter-peace forces to secure their own survival. Yet this support is often limited and pragmatic, rather than based on shared interests or ideological conviction. It does not constitute durable political alliances, but is above all an expression of not having other viable political alternatives. More worrying is the ideological pull of extremist movements, which rose as a result of the War on Terror. This war's global nature supplied the recruitment drive of extremist movements with a defensive rationale that turned jihadism from a locally focused insurgency into a global endeavour:Footnote 96 Islam is imputed to be under threat around the world and needs to be defended by all its followers. But here again recruitment of extremist groups benefits from external and domestic forces that have dislocated the individual. The combination of poor state services, dispossession by extractive industries and displacement by environmental degradation have created avenues for new counter-peace movements to forge alliances with local populations as the spreading of the jihadist insurgencies across the Sahel region demonstrates.Footnote 97

In limited counter-peace situations, peace formation agency is often contained either within the limited peace zone or seriously constrained in the space where counter-peace is rampant. For instance, what enables localised peace in countries such as Ghana, Kenya and Uganda, Malawi, and Nepal is the presence of a loose national and local infrastructure for conflict prevention and conflict mitigation.Footnote 98 Local peace committees tend to generate informal and temporal peace arrangements, which address outstanding disputes in the short run, but are often undermined by limited national support, resources, and rapidly changing ecologies that sustain conflict. In order to permanently resolve conflicts at the local, regional, and interstate level, regional and global powers need to think beyond stabilisation of power structures and support peace formation in its most subaltern forms.

Hence, the limited counter-peace pattern is characterised by a stability-focused alliance between the militarised quasi-state and its international backers, at the expense of civil society and social movements. Peace formation, which may hold governments to account and offer localised conflict resolution is fenced in by the stabilisation paradigm. This not only delegitimises the international peace architecture locally and internationally, but makes the limited counter-peace pattern vulnerable to slippage into the unmitigated counter-peace.

Unmitigated counter-peace

This cluster of cases is characterised by severe oppression, in which human rights are systematically violated across the country (that is, dictatorships, military regimes, and civil/interstate war). Counter-peace forces in such contexts operate largely unchecked and take over the state, constituting a modern Hobbesian Leviathan. Power asymmetries between elites and the population are stark. Between the state and society lies not a space for civil society, but a vacuum.Footnote 99 Participatory features (if they exist at all) are rigged in a way that they are unable to generate power shifts away from the incumbent regime. In this pattern, a predatory, Leviathan-like state dominated by cultural, business, and military elites has thwarted the emergence of civil society and kept the IPA at bay. It is forever on the lookout for geopolitical and security alliances to support its crude strategies of power accumulation. Domestic elites seek alliances with similar geopolitical and ideological counter-peace forces on the international stage, threatening the formation of a more substantial counter-peace architecture.

At the epicentre of the unmitigated counter-peace lies the ‘fierce’ state, ‘which is so opposed to society that it can only deal with it via coercion and raw force’.Footnote 100 It tends to emerge from a history of power struggles between domestic and regional rivals, often combined with anti-colonial struggles. In a political environment characterised by radicalised social forces and other forms of inbuilt instabilities, factions that emerge victoriously tended to embark on ‘defensive state formation’:Footnote 101 cementing their hold on power through a plethora of security institutions that focus on the ‘internal threat’. In the process of eliminating competing centres of power, domestic elites incorporate the economic ruling class into their regime, dismantle civic associations, and control the media.Footnote 102 Hence, the fierce state has over-developed its ‘despotic power’Footnote 103 and uses it free of constitutional or external constraints. What it lacks is the infrastructural power to regulate social processes peacefully. Above all, the fierce state is a vehicle to cement an authoritarian regime's hold on power (in collusion with geopolitical supporters), but it can also constitute an outward mode of governance, directed at a territory under external military control (for example, Israel's military occupation of Palestine, the US-led occupation of Afghanistan, or Russia's control of regions in Eastern Europe).Footnote 104 The oppressive nature of the fierce state is frequently mirrored by its violent contestation, turning civil wars into another manifestation of the unmitigated counter-peace pattern.

On its own territory, the fierce state is protected by the UN Charter, which threw its weight behind non-intervention in sovereign states as a safeguard for the self-determination of postcolonial countries. The Charter's simultaneous pledge to protect human rights ought to limit authoritarian regimes’ ability to use sovereignty as a smokescreen for systematic rights abuses. However, the practice of international relations ended up neither confirming a consistent commitment to sovereignty nor to human rights in clashes between the two norms. Instead it proved the critics right who saw in both pledges ‘a veil masking the restoration of a great power directorate’.Footnote 105 At a UN Security Council session in 2015, the representative of New Zealand stated: ‘the use of the veto or the threat of the veto is the single largest cause of the Security Council being rendered impotent in the face of too many serious international conflicts.’Footnote 106

Hence, systematic human rights abuses of an unmitigated counter-peace require either indifference of UN Security Council members or their active support. In cases in which they cared, the P5 have developed a whole range of tools to circumvent the UN's principle of non-intervention in sovereign states:Footnote 107 from subtle mechanisms (for example, using aid dependency to leverage intervention) to bypassing the UN (for example, in NATO's Kosovo intervention), establishing the principle of the Responsibility to Protect (used in Libya in 2011) and inventing ‘preemptive war’ (to justify the US occupation of Iraq). In other cases, in which geopolitical ambitions outweighed normative considerations, liberal as well as authoritarian governments have been protecting fierce states by ignoring severe human rights abuses, providing aid to dictatorships, financing proxy wars and shielding military occupations against the application of international law.

Since the start of the Arab Uprisings ten years ago, external pressure on dictatorships to respect human rights has given way to transnational support for authoritarian stability. In the beginning of the uprisings, some scholars believed that liberal internationalism had forged an ‘iron cage’ for dictators, which forced aid-dependent autocrats onto a political trajectory that they could not entirely control.Footnote 108 Yet as soon as this mechanism had facilitated the fall of the dictators Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt in 2011, it became defunct. In fear of heightened instability and rising fundamentalism in Europe's southern neighbourhood, resulting in increasing northward migration, Western foreign policy shifted from liberal conditionalities to embracing new and old dictators in the Arab region.Footnote 109 Faced with the resulting political and humanitarian challenges of the new wars in the Arab region (Libya, Syria, Yemen), liberal internationalism has all but collapsed.Footnote 110 Rather than empathy and support for democratic movements in Syrian and Yemen, mass migration fuelled xenophobia and Islamophobia in the West and empowered far right-wing forces to fragment the EU, support for the UN, and has divided Western societies.Footnote 111 Hence, counter-peace alliances not only prevented democratic regime change from being a principle guiding UN-intervention. They established regime stability, itself a code for authoritarianism, as a norm of regional security.

In order to compensate external backers for their investment in propping up the fierce state, contentious forms of resource extraction might fuel further tensions making a peace process impossible (yet necessary) in all of these cases. Syria's and Mali's payments to Russian mercenaries, for instance, curtail the state's resources for reconstruction and services as much as they turn notorious mercenaries into a permanent fixture of a postwar politics.Footnote 112 Their interest in any peace process would benefit a victor's peace, enforced by authoritarian conflict management: in other words, a counter-peace.

Russia under President Vladimir Putin illustrates how the backsliding of a democracy into dictatorship combined with decades of geopolitically justified tolerance of systemic human rights abuses can help to create a central driving force of a global unmitigated counter-peace process. In his first term as president of a democratic Russia, Vladimir Putin still had to justify his power (having been elevated from obscurity to the highest office in Russia) and his actions. Engineering a national emergencyFootnote 113 helped establish Putin as the guarrantor of security and stability as much as the principle that the needs of national security justify war crimes and crimes against humanity abroad. Crucial for his external counter-peace approach in Russia's neighbourhood was that investigative journalism, whistleblowing, and public criticism of the regime had to be crushed,Footnote 114 extending the lawlessness of foreign interventions to the treatment of Russian society. Democracy thus had to be rolled back. Consequently, elections became rigged, media muzzled, civil society controlled, and statehood personified to turn a democracy into a fierce state.

Moreover, a new ideology was needed to allow Putin's return to the presidency in 2012 since his promise of stability now looked like stagnation.Footnote 115 Economic integration with the EU to compensate for Russia's lost empire was off limits since Putin's authoritarian, lawless, and oligarchic regime was incompatible with law-focused systems such as the EU.Footnote 116 Consequently, he constructed a ‘Eurasian’ integration model as a spoiler system to reverse engineer the EU.Footnote 117 The latter failed since ‘Eurasia’ offered little economic prospects, appealing only to dictators with impoverished economies. When more former Soviet states pursued a path of Western integration, the Kremlin devised an aggressive foreign policy to thwart their ambitions and expose the EU's political and military weaknesses. Putin's destabilisation strategy of hybrid warfare, occupation, and rigged referendums allowed his regime to control Abkhazia, South Ossetia, the Crimea, and parts of the Donbas. In addition, the Kremlin expanded its sphere of influence on other continents since 2015: by restoring Syria's dictator Bashar al-Assad through ‘fascist forms of violence’Footnote 118 and through the involvement of Kremlin-linked mercenaries in many conflict contexts.Footnote 119 Since these challenges to the international rules-based order met no serious opposition, the Kremlin might have expected that its 2022 war on Ukraine would not result in serious consequences for Russia either. In this sense, allowing the erosion of the IPA nurtured the emergence of a driving force of a global counter-peace process.

Ideologically, Putin aims to counter the Enlightenment ideology of freedom, equality and fraternity with the restoration of orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationality.Footnote 120 His counter-revolutionary approach to thwart the ambitions of Ukraine's (2004/5 and 2014) and Georgia's (2003) revolutions is mirrored in the Kremlin's global counter-peace strategy in international peacemaking: By joining military coercion with covert actions and disinformation, while manipulating the instruments of the IPA (diplomacy, humanitarian and development aid, international law) to achieve war aims, Putin's regime is proposing an illiberal alternative to the liberal peace agenda, geared to achieve pacification rather than emancipation.Footnote 121

Peace processes could only end conflicts in the unmitigated counter-peace pattern if a multitude of tools of the IPA are aligned and simultaneously deployed. This would synchronise the IPA with subaltern political claims, neutralising the repressive capacity of the fierce state (see Figure 3). Paving the way for peace in this pattern might also require an impartial investigation into the embedding of violence and crime in the everyday functioning of governing institutions.Footnote 122 Due to the divisions in the UN Security Council (with one P5 member now constituting the centre of a global counter-peace process), such concerted interventions are currently unavailable. Instead, UN-authorised peace interventions in unmitigated counter-peace contexts are often ineffective single-track missions, which ultimately erode the IPA rather than create peace: mediation without peacekeeping, effective arms embargoes or no-fly zones (for example, Syria);Footnote 123 stabilisation without rights, democratisation, or security sector reform (for example, DRC);Footnote 124 reconstruction and humanitarian aid without building a state, democratisation or peace negotiations conducted on the basis of international law (for example, Israel/occupied Palestinian territories); sanctions without a wider peace process (for example, Belarus, Myanmar). In both Palestine and Afghanistan, brutal military occupations have discredited simultaneous peace interventions to the extent that local populations have at times shifted their allegiances to local counter-peace actors (for example, in the 2006 Hamas election in Palestine and the 2021 fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban).

Figure 3. Unmitigated counter-peace pattern.

Disconnected from the larger interventionary toolbox of the IPA, limited counter-peace interventions cannot be used as an entry point for a wider peace process. Indeed, such limited interventions may dress up counter-peace processes in the disguise of peace. Russia's military support for Syria's Assad regime and its simultaneous hosting of peace negotiations in the Astana process, for instance, has allowed Bashar al-Assad to participate in a pseudo ‘peace process’, while rejecting any compromises in peace talks and engineering a new state and society through coercion.Footnote 125 Syrian communities meanwhile have been bombed into consenting to local peace agreements, which ensure little more than their bare life. Supporting this process to its bitter end will implicate the UN in the formalisation of the unmitigated counter-peace in Syria. Similar dynamics may soon be at play in Ukraine as they have been in the Israel/Palestinian peace process in the past.

While the fierce state is mostly geared towards coercing its population (and the international community) into submission, alliances between segments of the population and counter-peace elites are possible through cultural institutions such as churches, media, or educational institutions.Footnote 126 In Russia, recent military invasions abroad have been popularised by media outlets and the Russian Orthodox Church, elevating the invasion of Ukraine to a ‘holy war’.Footnote 127 Since overt individual resistance in such contexts might be too dangerous, large parts of the population may opt for voluntary subservience,Footnote 128 covert forms of resistance,Footnote 129 or fully-fledged attempts at revolution with few viable options in between.

Conclusion

Drawing on the counter-revolution literature, this article has traced the emergence of counter-peace processes, which systematically block peace processes. It understands counter-peace as proto-systemic processes that connect spoilers across all scales (local, regional, national, transnational), while also exploiting structural blockages to peace and unintended consequences of peace interventions. Yet counter-peace processes are not necessarily the opposite of peace processes. Instead, they can mimic a watered-down version of a peace process, in which the hierarchies, inequalities and forms of marginalisation that fuelled the conflict are preserved, but where stability is restored through pacification. They can also constitute parasitic processes, in which spoilers take over peace interventions supported by the IPA in order to erode their emancipatory potential. Based on this understanding, the article investigated three questions: Which factors consolidate or deteriorate emerging conflict patterns? Is the IPA harbouring the dynamics of its own undoing? And, are blockages to peace systemic enough to construct a sedimentary and layered counter-peace edifice?

This article has elaborated three types of counter-peace systems with distinct sets of blockages, seen across different conflicts worldwide. In the ‘stalemate pattern’, violence remains proscribed, while the ‘limited counter-peace’ and the ‘unmitigated counter-peace’ demarcate a fluid spectrum of violence in which conflicts might shift. Yet this article suggests that certain factors (identified in the three patterns) may escalate conflict from one pattern to the next.

At the epicentre of these patterns lie different core blockages: The stalemate pattern revolves around a formalised political unsettlement, which materialises either as ethnic segregation along disputed borders or as a deeply flawed power-sharing agreement. By contrast, the limited counter-peace pattern centres on the inadequacies of the quasi-state. In this category, pockets of a country are violently contested. If the counter-peace elites that are driving violent state formation processes receive sufficient external support, conflicts may escalate into the unmitigated counter-peace category. International peace actors are then placed in an invidious trap: unable to hold to account or withdraw, with no possibility to support civil society or social movements, when devious counter-peace actors manipulate the normative endeavour of a peace process for their own interests. At the core of the unmitigated counter-peace lies a fierce state, which allows dictatorships or military occupations to coerce populations into submission.

All three core blockages are difficult to tackle since the epicentre of the counter-peace also constitutes the core of the existing political and social order, often related to geopolitics and the international political economy. Consequently, peace actors often do not dare to challenge the central form of political organisation. The quasi-state would need massive investment and intervention to turn from a core blockage into the foundation of peaceful social orders. The fierce state in the unmitigated counter-peace pattern, by contrast, is often protected against peace-related interventions by powerful external interests. Systemic change would be required for peace under these conditions. In order to tackle this issue, the wider UN system would need to be reformed.

In all three patterns the external environment is crucial to the perpetuation and escalation of conflict. Geopolitics, alliances between autocrats, structural violence, and vested interests in resource extraction constitute important factors that perpetuate conflict dynamics in all categories analysed in this article. Peace interventions are constrained by these counter-peace forces, possibly more than they are shaped by transnational or international norms. If external interests (rather than analysis of the root causes of the conflict) determine the exact choice of approach within a certain interventionary practice, the failure of peace interventions is all but guaranteed.Footnote 130 This failure needs urgent attention, since counter-peace processes increasingly control political and international order. Other blockages are more pattern-specific. Importantly, alliances between parts of the population and counterpeace elites are possible in all three patterns.

Our three patterns highlight not only the severe limitations of the IPA, but also its internal contradictions and infiltration by counter-peace forces. In the stalemate pattern, the peace process itself has been captured by counter-peace elites, even where there are plausible alternatives. In the limited counter-peace pattern, an effective peace process would need to create legitimate sociopolitical orders. Instead, external stability-oriented interventions have often aggravated the dysfunctions of the quasi-state. Interventionary practices such as statebuilding and counterinsurgencies have reinforced the coercive state apparatus and supported its rulers’ authoritarian tendencies. This renders the quasi-state unable to regulate social processes peacefully. It might even propel the slippage of conflicts from limited to unmitigated counter-peace. Once the unmitigated counter-peace pattern has been reached, the IPA encounters a systemic impass: while effective peace processes would require the simultaneous deployment of a whole array of peace interventions, counter-peace actors block all but minimal and therefore ineffective interventions. Such minimal interventions, in turn, may discredit the IPA along with the ‘peace’ that it supports. Given the internal and external contestation of the IPA, its many instabilities are unsurprising. It exists by virtue of its necessity, and yet all three patterns indicate that the IPA has been captured or eroded by counter-peace forces.

What this article illustrates is how counter-peace systems can be forged through connections between intentionality, structural forces, and the unintended consequences of interventions. Hence, the preliminary observations presented here point to a combination of ad hoc linkages between blockages and deliberate coordination between counter-peace forces. Yet, a closer look into these connections (which remains beyond the scope of this article) is needed in order to fully answer the question whether a stable counter-peace architecture has emerged in the shadow of its peace-promoting equivalent.

Our research suggests that counter-peace is proto-systemic. Its empirical range means it is connected to the problems that the many anti-colonial and postsocialist projects since 1945 and 1989 faced in holding off authoritarian power, building rights regimes and accountability, development, and preventing corruption. The disaggregated tactics and strategies of the counter-peace amount to several related attacks on the emancipatory project that the IPA was supposed to support:

(i) attempts to negate civil society networks’ transversal potential, as well as related revolutionary movements’ agency;

(ii) camouflaged attempts to reconstitute and reframe elite power often through the state and capital to divert economic resources;

(iii) to negate and disrupt local alliances with the UN's peace and donor system, with multilateralism, and with global civil society.

Practices like peacekeeping, peacebuilding, development, mediation, and conflict resolution are thus being hollowed out. Counter-peace processes further represent an attempt to modernise, perpetuate, or restore scalar stratifications through which elite power has historically operated. Counter-peace forces do so even without starting conflicts and wars that similar ‘restorations’ often led to in the past.

In sum, counter-peace processes aim to neutralise emancipatory processes while exploiting the stabilisation elements of the IPA. Elements of the IPA are implicated in this reversal, which effectively is a rejection of the expanded political claims of the Global South, including the IPA's focus on only basic human rights, limited democratisation, stabilisation, counter-terrorism/counter-insurgency, sovereignty and the security-state, along with narrow, Eurocentric conceptions of the ‘international’. A future research agenda that emerges from counter-peace's delegitimisation and defanging of the IPA might revolve around its decolonisation in order to respond to its hidden counter-peace dynamics. This would require a constitution of a more pluriversal peace architecture, a urgent task if conflict, war, and violence are to be avoided.

Acknowledgements

This article was funded by the UK government Global Challenges Research Fund (project ‘Understanding Blockages to Sustainable Peace and Development’), The University of Manchester, UKRI and the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the University of Manchester, GCRF, UKRI, the European Union, or European Research Executive Agency (REA). Neither the European Union, GCRF, UKRI, the University of Manchester nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.