Among the ways in which the seemingly inconspicuous year 1837 proved eventful for Russian history was the appearance of a new phenomenon in the country's social order.Footnote 1 In January of that year Konur-Kul΄dzha Kudaimendin, a local official holding the title of “senior sultan” in the empire's Akmolinsk regional department, became the first Kazakh to receive a certificate granting noble status. Within a few years, two other senior sultans had also received this distinction, and other requests for noble status followed.Footnote 2 When Russia's first all-imperial census sought to count the country's population in 1897, it revealed just over 1000 Kazakh nobles. An ethnically Kazakh contingent of the imperial Russian nobility had come into being.

Probing the manner in which such Kazakhs attained noble status, this article opens a window onto a curious and neglected aspect of the country's social history. Recognizing that nobility is typically associated with landowning in a feudal socio-economic order, we explore the process by which it also found application in the Kazakh steppe. Based on petitions, ethnographic accounts, and a comparative discussion of noble status in the Russian empire, we propose that the distinct character of nomads’ social and cultural existence differentiated the Kazakh nobility from its counterparts elsewhere in the empire, even as such Kazakh nobles did in fact become members of Russia's most privileged estate. The material that we present allows for both a wider conception of the Russian empire's nobility and a deeper understanding of the transformation of Kazakh nomadic society in the modern period.

More broadly, we propose that our account offers valuable insights on the character of the Russian empire across an important transitional period extending from the 1820s to the early twentieth century. Russia in this phase arguably embodied “empire” in two distinct senses. It was, first of all, a composite state with early-modern roots, made up of different peoples and regions ruled by a hereditary non-national dynasty (akin to the Hapsburg and the Ottoman empires). From this vantage point, the Kazakh nobility warrants comparison with Russia's other nobilities. Here we find that nobility offered the traditional Kazakh elite a route to maintain its privileged status in Kazakh society and, in effect, to translate that status into terms intelligible beyond the steppe itself. In this sense, the formation of a Kazakh nobility represented an extension into steppe society of a key instrument of state-building—the co-optation of existing elites—forged already in Russia's early-modern age. In a second sense, “empire” could signify a multinational state featuring the subordination of culturally distinct and ostensibly “inferior” peoples to a core, dominant nation (akin to modern colonial overseas empires). Empire in this second sense invites a comparison of the Kazakh nobility with other mechanisms for ruling the steppe in a colonial sense, such as the creation of new offices for Kazakh servitors in the 1820s, efforts to “civilize” nomads through law, the regulation of Kazakhs’ religious affairs, and the participation of Kazakh intermediaries in the production of knowledge about the steppe.Footnote 3 Here our analysis reveals that noble status was available not only to the traditional Kazakh elite, but also to ordinary Kazakhs, as long as they could compile the requisite service record or accomplishments. In this respect we see the Kazakh nobility not only as a way of recognizing an already existing traditional nomadic aristocracy, but also as a method of creating a new native elite beneficial to a colonial government that aspired to exert greater direct control over the steppe.

At the heart of all of this stands Russia's socio-legal order itself. The “imperial turn” of recent years has rightly drawn attention to the imperial dimension of historical problems previously analyzed exclusively or primarily as “Russian” issues. The question of soslovie represents a promising terrain for extending this approach and for linking analytically processes characteristic of the Russian center and its more distant regions into a single, all-imperial framework.Footnote 4 For Jane Burbank the very institution of soslovie itself, as well as the accompanying consciousness of group-based rights, was a product of imperial governance, which embraced, institutionalized, and legitimized difference.Footnote 5 The issue of estate status in borderlands or ethnically and religiously mixed areas of the empire was especially complicated and thus offers new insights on the nature of the soslovie order.

While historians have long recognized the multi-national character of the imperial Russian nobility, the experience of its (semi-) nomadic Muslim and Buddhist members has largely evaded historical inquiry. Even Soviet historian Avenir Korelin's foundational study of Russia's late-imperial nobility assumed that the nobility was a sedentary group and thus offered little discussion of the country's nomadic societies. Similarly, Andreas Kappeler's multi-national history of the Russian empire, while showing that the imperial nobility included some Muslims, offers only equivocal observations about members drawn from nomadic society. Nor does Boris Mironov, in a massive social history that otherwise highlights various attributes of Russia's nobility, explore the co-optation of nomadic elites into its ranks.Footnote 6 Those studies that actually do address Russia's Muslim nobility mostly examine Tatars of the Volga-Ural region, though there has also been some recent work on Crimean murzas and Bashkirs.Footnote 7 To be sure, a few historians have noted the existence of a Kazakh nobility in broader histories of Kazakhstan.Footnote 8 But even in the republic itself, few have explored specifically the incorporation of the Kazakh elite into the empire's highest estate.Footnote 9 The problem of the Kazakh nobility thus remains essentially unstudied.

In the text to follow, we first explore the routes by which members of Kazakh nomadic society made their way into the empire's most privileged estate. We also ask which specific privileges hereditary nobility conferred on members of the Kazakh elite, and why exactly they aspired to this status. To what extent were nomads seeking noble status cognizant of specific noble privileges—above all the ownership of land and, until 1861, serfs—and to what degree did they see those privileges as relevant to them? Did the acquisition of noble status induce Kazakhs to alter their pastoral way of life? By exploring these and related questions, we propose to show that service represented the principal basis for the entry of the traditional Kazakh nomadic elite into the noble estate, but that despite this entry these new nobles never enjoyed the full estate rights of nobility.

The Nobility Opens to Kazakhs

Traditional Kazakh society featured a division of people into an aristocracy known as the “white bone” (ak suyek) and ordinary Kazakhs, or “black bone” (kara suyek).Footnote 10 Kazakh sultans, representing the descendants of Chinggis Khan and hodjas claiming descent from Arab Islamic missionaries, could belong to the white bone group. Occupying a privileged position in nomadic society, these sultans were entitled to exploit the best pastures of the tribe and clan. Significantly, this aristocracy was more insular than the Russian empire's nobility: There was no route for those outside of this group to enter.Footnote 11

As Russia expanded toward the steppe, its rulers confronted the question of whether to recognize a Kazakh elite and what relation it should have to Russia's existing social hierarchy. One of the state's earliest considerations of the matter came in a session of the imperial Senate in 1776, which resolved that Kazakh sultans could be regarded as “princes.”Footnote 12 This was a revealing decision, for on the one hand it acknowledged sultans’ elite origins, but on the other it left precise definitions open: the title of “prince” was used by Russian, Tatar, and Kalmyk elites, but in the case of each group it had distinct juridical connotations. The scholar Said Murza Enikeev proposes that rulers used “princely title” in the sixteenth century to denote those notable Tatars who exercised authority over sizeable groups of their fellows. But their status remained complicated and varied depending on particular periods and rulers. Under Catherine II, Tatar princes were inscribed into genealogy books as stemming from “distinguished foreign lineage” (inostrannye znatnye rody).Footnote 13 Toward the end of that century, in 1797, Emperor Paul ordered that such princes not be included among Russia's princely families in conjunction with the creation of a general heraldry (gerbovnik) of the empire's noble clans.Footnote 14 Many of the Tatar clans that had proven their nobility in their respective provinces at the turn of the eighteenth to nineteenth century were confirmed as untitled nobility.Footnote 15 For the Kazakh nomadic elite, princely title brought no tangible benefits, and Kazakh sultans acquired neither equality with other princes in Russia nor noble status itself. The fact that the descendants of Kalmyk khan Kho-Urliak attained noble status only in the 1740s—long after their predecessor received princely title in the seventeenth century—suggests that the imperial government deployed a similar approach with respect to other nomadic subjects.Footnote 16 As the nineteenth century began, then, ennoblement was not yet explicitly a possibility for Kazakhs.

Helping to create that possibility was the fact that Russia's nobility already represented a complex and diverse formation. Nobles were divided into those with and without titles (prince, count, and baron) and those with personal versus hereditary nobility. Among the latter group alone, there were six categories that gestured towards the different ways in which the people in question had attained noble status.Footnote 17 Nor was ethnic diversity alien to Russia's nobility given its inclusion of a series of regional and national elites in previous centuries: descendants of the Baltic German knights, Polish magnates and the szlachta, Bessarabian boyars, the Ukrainian Cossack elite, and so on.Footnote 18 Based on the census of 1897, Avenir Korelin has shown that ethnically Russian hereditary nobles constituted only 53% of their estate, with the rest being Poles (28.6%), Georgians (5.9%), Turco-Tatars (5.3%), Lithuanians and Latvians (3.4%) and Germans (2.0%).Footnote 19 This distribution shows that the tsarist government had long before established a legal foundation for the entry of local elites into the empire's most privileged estate, using them as social support for the incorporation of different regions into the empire.Footnote 20 To be sure, internal diversity was quite typical for nobilities in Europe more broadly, but Russia was surely distinct in that its nobility grew to include not only sedentary Muslim elites but also (semi-) nomadic ones from among Bashkirs and Kazakhs, as well as Buddhist Kalmyks.Footnote 21

Kazakh ennoblement was closely related to reforms in the steppe in the third decade of the nineteenth century. Even if Petersburg had begun to regard the Kazakh Steppe as part of the Russian empire a century earlier, a more deliberate process of incorporating steppe society into the empire's administrative and social order began in the 1820s. The central legislative act initiating this process was the Statute on Siberian Kazakhs (1822), which applied principally to those in the Middle Horde, south of Russia's regional administrative center at Omsk.Footnote 22 As part of Petersburg's rejection of the older strategy of ruling the steppe through Kazakh khans, the reform created a new position of “senior sultan” (starshii sultan), who was elected by other sultans for a three-year term to supervise a given administrative-territorial steppe district under tsarist authority.Footnote 23 Such servitors were tasked with locating captive Cossacks or Russians, participating in diplomatic missions to Bukhara and Khiva, guiding scientific expeditions, and so on. The statute of 1822 explicitly identified the route by which such senior sultans could receive noble status, declaring that each “senior sultan” should be “recognized and esteemed everywhere with the military rank of major” and should be “regarded as being among the most respected sultans” even after the completion of his term of service. Most importantly for our purposes, “if he should serve three terms, he has the right to request a certificate granting the distinction of nobleman of the Russian empire.”Footnote 24 New legal provisions in 1824 for the Junior Horde, to the west of the Middle one, provided less detail on such matters and made no specific reference to ennoblement. But they did provide comparable Kazakh servitors with the military rank on the basis of which some would successfully request noble status later.Footnote 25 Thus the empire's growth and the need to encourage local elites to occupy new administrative posts created possibilities for the nobility's expansion. In the steppe, those new occupants could really only come from among nomads.

The example of Baimukhamed Aichuvakov shows how service could result in ennoblement. On January 22, 1836 he received his first rank, “host elder” (voiskovoi starshina), and three years later he became lieutenant-colonel, a year after that colonel, and in 1847 he became major-general for his uncommon service assisting the government's punitive operations against insurgent Kazakhs and detaining nomads who had attacked outposts or rustled livestock on the military line. During that time he also received imperial decoration, among others the order of St. Stanislav third degree (on May 1, 1837).Footnote 26 His rank of major-general gave him the right to request noble title, and this same rank also served as the basis for his grandson Ibragim Baimukhamedov's attainment of nobility later, in 1915.

Here we should emphasize that, especially early on, sultans had the inside track in the attainment of noble status, because the posts conferring that status were reserved for them. Thus the 1822 statute sought to preserve the position of the descendants of Chingissids—those sultans who had the right to occupy the posts of senior sultan and volost΄ head (volostnoi upravitel΄). Likewise, on the territory of the Junior Horde further west, separate provisions authorized as potential sultan-rulers—sultanty-praviteli, a post comparable to senior sultans created in 1824—only those descended from sultans.Footnote 27

Yet even as the 1822 statute indicated Kazakhs’ route to ennoblement (at least in the Middle Horde), the process was not automatic. The provisions just noted in fact made no specific indication concerning precisely how noble status was to be obtained, which implied that the empire's general laws on such matters pertained to Kazakhs as well. Such laws dictated that one who had attained a certain rank through service would be recognized as noble without any special confirmation of this fact. But a footnote to the relevant article in the Law Digest declared that Siberian inorodtsy—native non-Russians, a group that included Kazakhs—would enjoy noble rights only if they received special certificates attesting to this fact. Kazakhs’ attainment of noble status through rank thus required an extra step.Footnote 28

If service of requisite length in the appropriate office provided one route to ennoblement, then awards and decorations offered another. Thus, for example, throughout the empire all awards at the first level, the St George's medal (at all levels) and St. Vladimir's (the first three levels) entitled its recipient to nobility.Footnote 29 For Kazakhs specifically a wider range of awards entitled them to noble status. Thus, for example, Derbisali Berkimbaev, an aide to the governor-general of Turgai Region, became a noble in 1900 thanks to his St. Vladimir's award at level four.Footnote 30 Here we can note a contrast with another historically nomadic group, Bashkirs, who sooner encountered obstacles to inclusion in the nobility at this time. By a decree in 1831 those serving in the Bashkir-Mishar host—a special military unit consisting mostly of people from those groups—were prohibited from acquiring nobility regardless of any awards they received. Thus a door open to Kazakhs was closed to Bashkirs.Footnote 31

Generally speaking, rank and award as a route to nobility for sultans characterized above all the period before the Great Reforms, because this was a crucial time of change in the steppe's administration. We have already noted the 1822 statute for “Siberian Kazakhs” and less detailed provisions for the Junior Horde in 1824.Footnote 32 The year 1854 saw the formal extension of the general laws of the empire into Siberian Kazakh territory.Footnote 33 And a decree of 1867 specifically prohibiting nomadic peoples—Kazakhs, Bashkirs, and Kalmyks—from requesting military rank reflects Petersburg's assessment by that point that nomadic regions had become internal provinces of the empire, which made the task of drawing the nomadic elite into Russian service less urgent. The decades before the Great Reforms were thus a period of active and dramatic administrative change. In order to accelerate that transformation, the imperial government sought to draw members of the nomadic aristocracy into state service and guaranteed them the preservation of privilege in exchange for their loyalty to the empire. In sultans’ service records we find, accompanying the granting of rank, decoration, or gifts, remarks such as “for zealous service,” “for zeal and devotion,” and “for devotion and assiduousness in service.” Yet even as they acquired noble status through rank and award, Kazakh sultans remained a traditional aristocracy in their own society. At this stage, then, one can speak of a symbiosis of traditional elite and Russian nobility, with the Kazakhs in question exhibiting characteristics of both. Nobility represented a way for the tsarist government to encourage Kazakh service and loyalty, and for the traditional Kazakh aristocracy to maintain its elite status over other Kazakhs. The resulting situation resembled the kinds of bargains with existing elites that had been a central feature of Russia's empire-building in the early-modern period.

Kazakh Nobles: A Profile

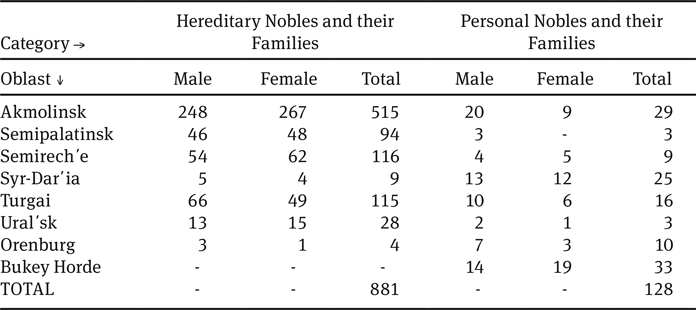

According to the census of 1897, there were a total of 1009 Kazakh nobles, 881 hereditary and 128 personal (see Table 1). This number constituted a mere 0.03% of the empire's entire Kazakh population, while Kazakhs made up only 7.3% the hereditary nobles residing on the territory of Kazakhstan and Central Asia.Footnote 34 By way of comparison, the census identified 964 hereditary nobles and 340 personal nobles among Bashkirs in Ufa and Orenburg provinces—that is, a comparable number (though the Bashkir population was smaller).Footnote 35 In contrast, sedentary Tatars could claim a significantly greater number: 8219 hereditary nobles in eleven provinces of European Russia, making up about 0.4% of the empire's entire Tatar population.Footnote 36

Table 1. Numbers of Kazakh Nobles by Region, 1897

Source: Pervaia vseobshchaia perepis΄ naseleniia Rossiiskoi imperii 1897 goda (St. Petersburg, 1904), vol. 28, 81, 84, 86, 87, 88.

A deeper comparison of Kazakh nobles with nearby Bashkir ones reveals both similarities and differences. In Albina Il΄iasova's assessment, all hereditary Bashkir nobles of Ufa and Orenburg provinces, much like their Kazakh counterparts, received nobility through meritorious service. Yet the two groups are different when we look at their origins. Bashkir nobles came predominantly from the ranks of ordinary Bashkirs—not least, presumably, because the number of traditional elites within the Bashkir nobility was very small. Il΄iasova finds that the majority of clan leaders among ordinary Bashkirs came from among “the sons of Bashkirs” (iz bashkirskikh detei)—that is, they had themselves been born into non-elite Bashkir families—and only two came from more elite backgrounds: one from a family of mirzas and the other from a family of princely tarkhans.Footnote 37 Thus if Kazakh nobles were drawn primarily from traditional elites—especially early on—then Bashkirs came to a much greater degree from more ordinary ranks. We should add, moreover, that Bashkirs by themselves represented a soslovie with distinct privileges, for example hereditary landownership, that were not shared by nearby peasants. It was in fact through both nobility and Bashkir status that St. Petersburg forged bonds of loyalty with this territory.Footnote 38 While ordinary Kazakhs enjoyed some privileges (freedom from recruitment and the poll tax, for example), they did not constitute a privileged estate in the ways that Bashkirs did.

The situation in the steppe bears more resemblance to that in Crimea, though the latter exhibited peculiarities of its own. Here as elsewhere the idea of nobility was grounded in both lineage and service. Some clans boasted roots going back to the Golden Horde, and the Giray dynasty could claim “white bone” status by descent from the Chingissid line. After annexation in 1783, the primary goal of the peninsula's mirzas—clan leaders and members of the Crimean Tatar elite—was to preserve the integrity of the elite and the prestige of mirza status; patents of Russian nobility could confirm that status, but only lineage could confer it. Service to the empire thus became both a mechanism for preserving such local social hierarchies and a tool of elite integration. Service and attainment of rank proved important for connecting the Crimean elite with Russia: from 1783 to 1850, 217 mirzas acquired civil or military rank, in 83% of cases at a level high enough to confer hereditary nobility. At the same time, the precise relationship of the Crimean elite to the Russian nobility remained unclear: Were the two distinct but equal? Was the first a subset of the second? Kelly O'Neill accordingly recounts a “series of ambiguous and contradictory policies that made it impossible to know whether a Crimean mirza would—or could ever—be a dvorianin (Russian nobleman).” For all but a minority of cases (40 of 295) a State Council ruling of 1840 ended the process of mirza ennoblement, while many members of the Crimean elite fled the peninsula during and after the Crimean War.Footnote 39 In this case, then, the process of ennoblement was even less clear than it was for Kazakhs, and it effectively ended earlier. At the same time, service and lineage combined in both cases to represent the basis for ennoblement, even as the balance between those two criteria shifted.

Indeed, the situation in the steppe began to change in the second half of the nineteenth century, as the tsarist administration ascribed more significance in appointments to education, upbringing, and devotion to service. In this context, non-elite Kazakhs gained more opportunities to acquire nobility. Earlier, in the 1820s–50s, tsarist administrators, still very much shaped by the estate system in Russia itself, were inclined to assume that those appointed to official posts should come from already privileged layers of society. Yet even at this early stage the situation was in fact more complicated. Over the course of 1824–68, of forty-three senior sultans at the higher level of district departments (okruzhnye prikazy) in the western Siberian jurisdiction, fully sixteen (37%) were of black-bone origins—that is, ordinary Kazakhs. At a lower level of administration, the volost΄, a more complicated picture emerges, even though the expectation was that sultans would be appointed here as well. Thus in 1839, of the sixteen volost΄ managers of Akmolinsk district only four (25%) belonged to the elite white-bone category, and in Kokchetav district only three of nine (33%) were of sultan status.Footnote 40

This situation raised questions about the government's tactics and whether it actually made most sense to uphold the traditional rights of the hereditary aristocracy in the steppe, or whether, alternatively, it might be better to promote a greater degree of competition among Kazakhs generally by opening the door to capable non-privileged Kazakhs such as biis (traditional judges who were sometimes also clan leaders) and elders.Footnote 41 In 1856 Orenburg governor-general Vasilii Perovskii questioned why the appointment of only sultans to important positions had become the norm, when in his view ordinary Kazakhs had provided “repeated examples” of excellent service and had revealed “honesty and aptitude” in dealing with diverse affairs. Furthermore, having studied ordinary Kazakhs’ way of life, Perovskii averred that in nomadic society sultan origins conferred “no substantive advantages” and that appointment of black-bone people to posts in the local administration would in no way violate Kazakh norms, for in the steppe “influence and respect are acquired exclusively by personal qualities.”Footnote 42 What this reveals, then, is a gradual modification of governmental priorities—namely, a shift away from origin toward personal qualities and loyalty in the conferring of noble status.

Even so, it is curious that if the majority of sultans acquired ranks or decorations entitling them to nobility earlier in the nineteenth century, their status was recorded in genealogical books of the noble assemblies only much later. Thus, for example, sultan Mukhamedgalii Tiaukin acquired the rank of colonel in 1860 but submitted a petition requesting noble status to the Orenburg Noble Assembly only in 1883.Footnote 43 In due course the descendants of both Kazakh nobles and Kazakh officials who were entitled to request noble status but had not yet done so also began to submit petitions for themselves and their progeny. For example, Ibragim Rysgaliev Baimukhamedov-Aichuvakov wrote with reference to the meritorious service of his grandfather, “I have in my possession no documents certifying that I am a hereditary noble,” and he therefore requested that the Orenburg Noble Assembly provide confirmation to that effect. Baimukhamedov-Aichuvakov accordingly received noble status for his grandfather's service, more specifically for the latter's attainment of the rank of major-general.Footnote 44

How exactly may we account for this delay? One reason might be that Kazakhs who acquired the appropriate rank were themselves not aware that they could seek inclusion in the nobility. Similarly important was the fact that, as nomads, Kazakhs had difficulty preserving the kinds of documents that they needed to fortify their application for noble status. One petition from 1914 provides a more direct answer. The petitioners—sultans and brothers of the Bukeikhanov family—explained that they had not sought noble status earlier for three major reasons: 1) because the surrounding population had already respected their personal and property privileges even without “explicit juridical certification”; 2) because they had been certain that state authorities themselves “would not fail to protect our rights when needed”; and finally 3) “because we did not expect such a rapid change in Kazakhs’ way of life.” Now that things were indeed changing, “we are compelled to seek the personal rights that the law grants to us, ones that confer certain privileges with regard to property in comparison to other, ordinary Kazakhs.”Footnote 45 This declaration suggests that the situation was changing rapidly enough in the steppe that privileges assumed previously to be broadly recognized by everyone now required more explicit confirmation.

A hereditary Kazakh nobleman generally could pass his title to his progeny, and many Kazakh nobles, upon receiving their charter, immediately petitioned their Noble Assembly for the inclusion of their sons. As Kazakhs usually did not have so-called metrical books on births, marriages, and deaths, confirmation of a petitioner's fatherhood was provided by letters from other honorable Kazakhs.Footnote 46 Here it bears emphasis that Kazakh nomads had a strictly patrilineal society. Thus while relevant legislation dictated that hereditary nobility could be transferred through both marriage and procreation, Kazakh nobles petitioned for the inclusion of their sons in their noble houses, but not their wives and only rarely their daughters (we know of only four Kazakh noble families that sought to include daughters).Footnote 47 In contrast, members of the Tatar and Bashkir nobility generally included their wives in their noble houses.

Titles among Kazakh nobles were rare, and it was only the representatives of the princely lineage of Chingissids (the Bukeis) who acquired them. This lineage descended from the Kazakh Khan Abulkhair (1710–1748) in the Junior Horde, from Khan Ablai (1771–81) in the case of the Middle Horde, and Khan Bukei (1815–17) in the case of the Bukei Horde. In all, we know of five such descendants who enjoyed both princely title and hereditary nobility.Footnote 48 Such Kazakh princes all received their education at the Page Corps, a privileged educational institution of the empire. The possibilities for career development thereafter are illustrated by Gubaidulla Chingiskhan, who emerged as a cornet of the Life-Guard Cossack regiment. Noticed by Alexander II at a military review, the young officer became an aide-de-camp, and in 1878 he became a member of the emperor's retinue. In 1879 the emperor personally bestowed hereditary nobility upon him, and a decade later, in 1888, Gubaidulla became a general-lieutenant and was ascribed to the army's cavalry reserve. For a time he also occupied an important position at the head of a special commission for the inventory of Muslim pious endowments (waqfs) in Crimea. Relieved of that post in December 1889, Gubaidulla returned from Simferopol΄ to St. Petersburg and was appointed to the interior ministry. After his retirement in 1894 he devoted himself to public life, becoming an avid theatergoer, a regular at the capital's English Club, and a member of a committee overseeing construction of a mosque in the imperial capital. On doctor's advice he move to Yalta in 1908 and lived with his older brother until his death in 1909.Footnote 49 Such, then, was the life of one Kazakh prince, who represents an especially noteworthy example of what was possible for those representatives of the steppe aristocracy who inserted themselves into the empire's higher society.

Thus the Kazakh nobility represented a subset of Russia's noble class on the basis of their elite standing in nomadic society, but especially as time elapsed they began to constitute a substantially new social group. The majority of the Kazakh nobility were of elite origin, as opposed to the Bashkir nobility, and in contrast to the European and Tatar traditional elites, Kazakh sultans were not automatically recognized by tsarist authorities as nobles. What we see, then, is the beginning of the transformation of the traditional organization of Kazakh nomadic society and the social integration of the Kazakh elite and then even broader elements of Kazakh society into the empire's most privileged estate.

The Rights and Privileges of Kazakh Nobles

Having both described the manner in which Russia's nobility opened to Kazakhs and provided a profile of those Kazakhs who actually entered the estate, let us turn to the specific rights and privileges that these Kazakh nobles enjoyed. Here we find that both the Kazakh pastoral economy and dramatic change on the steppe in the last three decades of the tsarist order exerted significant influence on what nobility actually meant for Kazakhs.

Russian imperial law granted all members of the noble class the right to a coat of arms, the ownership of serfs (before 1861) and land, middle and higher offices in the Russian administration and army, and exemption from conscription and taxes. Entered into the noble societies of their provinces, they also had rights of self-government in the form of the noble assembly. To what extent did Kazakh nomadic nobles perceive the significance of these key privileges?

The coat of arms established a family's right to hereditary propagation of noble rank and titles and made it “visible.” A coat of arms communicated the family's origin, privileges, and information regarding the military and civil accomplishments of its individual members. Such coats of arms were created by the nobles themselves, who sought to present their origins and distinguish themselves from other families before the government. Although the Russian empire's catalog of all noble families’ heraldry began in 1797, no more than one-fifth of the noble families in the empire had coats of arms.Footnote 50 Some Kazakhs were among them. Kazakh noble dynasties like the Chingissids, Baitokins, Bukeis, Gazybukeis, Tezekovs, and the Kochenovs had their own coats of arms, and some—though by no means all—were included in the empire's General Catalog of Heraldry. For instance, the coat of arms of the Baitokins (granted on August 1, 1853) was entered into the General Catalog and described in considerable detail.Footnote 51 Also included is information regarding the method by which the sultan received his noble title and the accomplishments for which it was granted.Footnote 52 The Baitokins’ coat of arms does not have any markings indicating the family's origins and thus demonstrated the humble stock of its owners and the role of service in their acquisition of noble title.

The coats of arms of the titled nobility were more complicated. The Chingissid princes had their own unique coats of arms, in which a crown and cape were prominent, indicating the Chingissids’ noble lineage—descent from Chingis Khan and the khans of the Bukei Horde—while the weapons on the coat of arms represented their military accomplishments, and two shield-bearers—one Mongol, one Kazakh—signified the continuity of the family's privileges from the time of the Mongol empire. Since Chingissids were the only titled noble family among the Kazakh people, there was only one Kazakh coat of arms for titled Kazakh nobles.

Certain noble privileges had only limited relevance for Kazakhs. Consider for example conscription. Exempted from recruitment both before and after the introduction of “universal” conscription in 1874, Kazakhs provided no military service until the empire's final hour. Ennoblement thus brought no benefit in this regard until 1916, at which point government efforts to draft Kazakhs into support services in the rear increased the number of petitions requesting recognition or confirmation of noble status.Footnote 53 Nor were there many advantages in matters of taxation, from which Russia's nobility was typically exempt. The interior ministry argued that the tent tax normally imposed on nomadic populations (kibitochnyi sbor) did not represent a personal tax, but rather payment for “the right to nomadism on state land, and in this sense does not in any way differ from other obligations, from which not one social estate in the country is exempt.” The Temporary Steppe Statute of 1868 indicated that the families of a few “honorable Kazakhs” were exempt from the tent tax in light of the special services that they performed for the government, but these exclusions were given individually and personally, not hereditarily. Because the Russian state had neither legislative norms nor precedent for such hereditary exclusion, a petition from the head of the Kazakh noble Baimukhamedov family, Mukhamedzhan Baimukhamedov, to release his progeny from the payment of the tax was declined.Footnote 54 A similar situation obtained with respect to the tribute tax known as iasak: it was not noble status that freed some Kazakhs from payment, but rather their occupation of posts such as senior sultan. Even then, liberation was only partial: Though “personally free from iasak,” such office-holders still had to pay the tax on the basis of their property.Footnote 55 Thus the nobility's general exemption from taxation had only very limited application for Kazakh nobles. And because the right to vote and attend noble assemblies was a function of the value of the nobles’ property—land holdings—Kazakh nobles generally had no basis for participation in such associations. That privilege, too, remained largely irrelevant to their way of life.

Soviet historian Avenir Korelin proposes that among nobles’ rights and privileges, the most important before emancipation was the right to possess populated estates, whereas afterwards the main indicator of the nobility's privilege involved their right to land.Footnote 56 What meaning did the individual ownership of land have for Kazakh members of the estate in light of their nomadic economy? Kazakh noble landowners encountered certain difficulties—having to do principally with the nomadic way of life and the particular relationship of nomads to the land—that Russian, Tatar, and Bashkir nobles did not. Materials like the nobility's genealogical books, service records, and the 1897 census indicate that a majority of Kazakh nobles (95% of hereditary ones and 60% of personal ones) still lived in nomadic encampments and engaged in migratory pastoralism. In nomadic societies, pastures were owned collectively by large familial groups, while livestock belonged to individuals and families. The strongest tribes and clans asserted rights to the best pastures, while weaker groups could use such land only after the departure of the stronger ones. Exclusive rights to land ownership by themselves had little significance and thus did not carry the same meaning that they did in sedentary, agricultural regions.Footnote 57 As a result, Kazakh sultans who gained noble title did not initially concern themselves with receiving individual plots of land. The Russian administration, for its part, was inclined to provide grants of land to Kazakh sultans only if beneficiaries planned to engage in arable farming. The petitions in the 1870s of two hereditary Kazakh nobles, major Aryslan Khudaimendin and colonel Ibragim Dzaikpaev, may serve as examples. The report of the general-governor of the Steppe notes that a plot with 500 desiatinas of arable land and 77 desiatinas and 1900 sazhens of non-arable land in the Akmolinsk district were granted to Dzaikpaev and Khudaimendin, respectively.Footnote 58 Though we lack further information on whether these nobles actually engaged in agriculture, Kazakh oral tradition offers insights on their kinsman and fellow noble Dzhalgary Baitokin, who indeed took up agriculture and called upon other Kazakhs to join in this pursuit.Footnote 59 Moreover, his eldest son Musa Dzhalgarin built wooden houses for himself and his relatives, thus inducing some twenty-five other Kazakh families to request of tsarist authorities that houses also be built for them and that they be allowed to engage in agriculture.Footnote 60

As the nineteenth century progressed towards the twentieth, Kazakh nobles began to petition more actively for plots of land. The larger context here is crucial: the last three decades of the empire witnessed a tremendous wave of peasant settlers from European Russia into Asia. As many as five million peasants crossed the Urals, and the northern portions of the steppe became an important destination that absorbed well over a million new inhabitants from the 1890s. This development produced numerous changes to Kazakh life, but for our purposes the most important is that new settlers put tremendous pressure on native Kazakh inhabitants and thus created new imperatives to solidify claims to the land.Footnote 61 Nobility represented one way in which Kazakhs could do this. More generally, as Virgina Martin remarks, “Russian rule dramatically changed the tools and terminology of land use in the context of decreasing access to quality pasture lands.”Footnote 62

The petition of a Kazakh noble, Ibragim Rysgaliev Baimukhamedov-Aichuvakov, illustrates this situation well. In it he noted that the Main Administration of Land Management and Agriculture (Glavnoe Upravlenie Zemleustroistva i Zemledeliia, henceforward GUZiZ) began cordoning off sites for Slavic migrants using Kazakh land in the Karachagansk volost΄ of Ural΄sk district, where he owned a plot. Being a hereditary noble, he contended that his lands were not meant for distribution among settlers, and he requested documentary evidence in support of his claim.Footnote 63 Similar kinds of petitions provide other insights. The sons of major-general Mukhamedzhan Baimukhamedov, Kazakh sultans and hereditary nobles in the Tuztiubinsk volost΄ of the Aktiubinsk Oblast, appealed to the GUZiZ for a grant of land larger than what was typically given to Kazakh nobles. Their petitions did not indicate their membership in the noble class and instead emphasized their father's accomplishments, his many awards, and his receipt of a portrait of “the now successfully reigning Emperor, signed by him during his highness's tenure as the heir.”Footnote 64 This petition was written in 1913 when the process of mass resettlement was in full swing, and this circumstance affected its adjudication. Laws ratified by the Council of Ministers in 1909 dictated that Kazakhs wishing “to engage in sedentary cultivation” could receive plots of land “no larger than 15 desiatinas per capita” on the same basis as migrants.Footnote 65 But no particular provision was made in this regard for Kazakhs still engaged in pastoralism. In a report to the GUZiZ, the military governor of Turgai oblast, Mikhail Mikhailovich Eversman, identified the need to make such distinctions “until the conclusive resolution of the question at hand.” He emphasized that he received a series of petitions from well-known and meritorious Kazakhs requesting that their lands, particularly pastures, be retained in hereditary tenure. He accordingly recommended that large pastoral households having “state-level significance” be preserved. He noted that with the increase of resettlement, pastoral enterprises were being supplanted by agricultural households of little use, ones that were at times even unprofitable. For this reason, he advocated encouraging pastoralism as the only form of enterprise in the Kazakh steppes.Footnote 66

In response, the GUZiZ proposed that the law erected “no barriers to larger grants of land” to Kazakh sultans and their progeny and therefore held that such grants could go forward if the petitioners were influential locally (which could help with Slavic settlement of the Steppe region) and maintained good relations with the government, and also if such grants were desirable to the provincial administration. Still, the GUZiZ contended, such supernormal land grants could only be chartered “with the blessing of the highest levels of authority.”Footnote 67 Alas, no conclusion on this matter was reached, but the nature of the Kazakhs’ request suggests that they themselves did not contemplate a direct connection between noble status and land. Rather than emphasizing their right to landownership as nobles, they relied instead on allusion to their “lengthy service” in local administrative organs or their parents’ “accomplishments” before the emperor. Ultimately, their concern was to secure the land not so that they could engage in agriculture but rather for use by their clans as pastures.

This analysis of the rights and privileges of Kazakh nomadic nobles suggests that the Russian authorities attempted to create a new social group in nomadic Kazakh society, even if that group had significant roots in the older Kazakh elite. Yet the process was a complicated and contradictory one. On the one hand, some Kazakhs now acquired noble certificates, the right to a coat of arms, and the opportunity for inclusion in the nobility's main corporate organization, the noble assembly. In this respect, it is possible to speak of a new formation in Kazakh society, a society that may previously have understood clan markings (tamgi) but had no conception of a coat of arms. Over the first half of the nineteenth century, the Kazakh population had become accustomed to the idea of receiving certain rewards from central and regional tsarist authorities for service in the form of military rank or medals. For members of the Kazakh nomadic elite, receiving certificates granting noble status represented a first step in the appearance of new social reference points and gestured towards a new status for the individual in Kazakh society. On the other hand, the foregoing analysis suggests that in fact the integration of these nomadic Kazakhs into the nobility remained quite superficial, given that these new nobles did not receive (or could not use) key privileges of the noble order, above all the right to land and emancipation from taxes. As noted above, the reasons for this had to do with the particularities of nomadic life and nomadic attitudes towards land.

Yet beyond the fact that the nobility in Russia was a heterogeneous body generally, by the late nineteenth century it also represented a socio-political formation in transition. True, historians express different views on the degree to which Russia's nobility in the empire's last decades was becoming a landowning class, defined less by legal status and soslovie consciousness than by occupation and economic interest.Footnote 68 But if we contemplate Kazakhs’ encounter with the institution of the Russian nobility, it seems safe to think in terms of the interaction of two systems that were themselves changing as they came into deeper contact with one another. In his seminal article in 1986, Gregory Freeze proposed that over the course of the nineteenth century Russia's estate system was actually still evolving—actively developing rather than disintegrating.Footnote 69 The steppe itself, meanwhile, endured transformation based on growing colonial intervention in matters of Kazakh administration, justice, and land use—all topped off by aggressive peasant colonization by the 1890s.Footnote 70 Thus if Russia's soslovie system was confronted with an increasingly complex and dynamic social structure as the nineteenth century unfolded (whatever the autocracy's commitments to that old system), and if Russia's nobility may have come closer to representing an interest group or class (despite some continued support for the principle of soslovie), then nomadic society itself developed greater familiarity with imperial structures and norms, while also facing growing pressures from colonial interventions of different kinds.Footnote 71 Kazakh elites thus faced the opportunity and the challenge of joining not a static social system, but one that was itself in the midst of transformation and growing politicization.

The incorporation of native elites into the empire's nobility represented a key strategy for building Russia as a composite multi-national state in the early-modern period. With some modification, this process extended to Muslim and Turkic groups like Tatars, Bashkirs, and Crimeans, and eventually to Kazakh nomads. It was with the last group, however, that this policy stopped: To our knowledge, the opportunity to join Russia's nobility never extended to the native population of Turkestan, Russia's most distinctly “colonial” possession.Footnote 72 Kazakhs were thus in effect the last ones to have this opportunity, with the door closing behind them. Their incorporation into the empire had begun early enough, in the eighteenth century, that early-modern elements of empire-building retained their relevance for their gradual entry into the empire's broader institutions and orders. The process for their ennoblement was itself outlined explicitly for the first time in 1822, when Russia was arguably only beginning to enter the modern age. Thus even as Kazakhs increasingly endured the kind of colonialism that characterized the “new imperialism” of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this important element of the earlier model of incorporation remained in place, albeit with the evolutions that we have described in this article. At the same time, we propose that the process of ennobling Kazakhs, starting as it did only in 1837, came too late to serve as an effective mechanism for truly integrating the Kazakh elite into an all-Russian imperial one. If in Russia proper the system's evolution had precedents earlier in the country's history, then for Kazakh nomadic society that system was entirely new and unfamiliar when it appeared in the 1820s. The emergence of a Kazakh nobility occurred against the backdrop of the replacement of an earlier nomadic system of authority—one that was itself evolving and had historically featured greater centralization than is typically allowed—by a bureaucratic and colonial one shaped by clear conceptions of progress and civilizational hierarchy.Footnote 73 This process naturally revealed all the peculiarities of such a transitional era. It remains hard to tell how matters might have developed had 1917 not intervened to eliminate the category of nobility entirely, but it seems likely that with formally recognized privilege these Kazakh nobles would have fared better than, for example, the Kazakh intermediaries who became dispensable as the empire committed itself fully to mass peasant resettlement.Footnote 74

The Kazakh nobility was distinct from other members of the larger estate for the reasons indicated above. Sultans constituted the largest portion of the Kazakh nobility, and our article has sought, among other things, to trace their adaptation to the new order. The result was a synthesis of the elite characteristics of those sultans and the imperial noble estate. Partly for this reason, Kazakh noble rights came into existence only partially. In the initial stages of their incorporation into the Russian administrative system, Kazakh servitors appear not to have been fully aware of Russia's estate order—though of course some exhibited greater familiarity than others. Thus many of those sultans who received rank and decoration entitling them to nobility did not ask to be provided with land, in accordance with their estate rights. Kazakh nobles knew and tried to use those noble estate privileges that were familiar and relevant to them. It would thus appear that for Kazakh nomadic society the noble distinction itself—and all the more so its corporate organization, including the nobility's local self-government—remained either alien or of limited relevance to their aspirations. Moreover, although general laws in principle provided all nobles with identical rights and privileges, distinct legislative acts regulated the situation for Kazakhs, sometimes with exclusions and exceptions at odds with those general provisions. These exceptions constituted an impediment to Kazakh nobles making full use of their rights.

For all that, the Kazakh nobility did become a part of Russia's highest estate, and its experience helps to reveal the diversity of the larger nobility, as well as the empire's differentiated social policy in relation to the country's distinct regions. Even among Turkic peoples—Tatars, Bashkirs, Crimeans, and Kazakhs—there were differences. Ultimately, despite its unique character, the Kazakh nobility displayed several characteristics of the Russian noble estate and partly used its privileges throughout the nineteenth century. But if nobility indeed offered one route to integration of Kazakh society into the Russian imperial social order, that integration remained gradual and still only partial by the early twentieth century. The phenomenon of nomadic nobles thus reveals both possibilities and limits of social inclusion for Russia's ethnically and culturally diverse population.