In 1940, Langston Hughes published his first autobiography, The Big Sea. Its epigraph read: “Life is a big sea/full of many fish/I let down my nets/and pull.”Footnote 1 The Big Sea, which follows Hughes to Africa, Mexico, Italy, and of course through the streets and avenues of Harlem, explores racial identity as part of a globally interconnected set of intimate, often titillating experiences. In one of the chapters, “Spectacles in Color,” Hughes begins with a vivid description of a “ball where men dress as women and women dress as men.”Footnote 2 Hughes was referring to Harlem's most notorious drag competition: the annual Hamilton Club Lodge Ball at Rockland Palace Casino (located on the corner of 155th Street and Frederick Douglass Boulevard). Years before, Hughes wrote about a similar “spectacle.” In 1934, he published an article in the American publication Travel Magazine titled “The Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan” which was based on interviews he conducted while traveling through Soviet Central Asia.Footnote 3

In “Spectacles,” we see Hughes reflecting on Harlem in the 1920s, a period in which he also served on the editorial team behind Fire!!, an African-American literary magazine best known for what Alain Locke called “its strong sex radicalism.”Footnote 4 Locke was likely referring to Richard Bruce Nugent's short story “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” whose publication in Fire!! marked one of the first depictions of black queer desire in print. For the black cultural establishment, led by figures like Locke and W.E.B. Du Bois, the depictions of black sexual “deviance” laid bare in the pages of Fire!! were counterproductive to the African-American community's struggle for social and political acceptance.Footnote 5 By airing the black community's dirty laundry, Fire!! according to Locke, would “shock many well-wishers” of the Negro cause, “and elate some of [its] adversaries.”Footnote 6 The pushback against Fire!! represents the complex nature of discourses of social progress within the African-American community during the inter-war era. Despite the proliferation of flappers and speakeasies throughout 1920s Harlem, the black middle class, focused on increased access and civil rights, tried to distance itself from the sexual libertinage of the era by engaging in what is now termed “the politics of respectability.” For them, Fire!! and the Hamilton Club drag ball were roadblocks, not pathways, to racial equality. In this piece I explore the ways that this context informs Hughes's Soviet writings of the subsequent decade, particularly where discourses of queer identity and social progress intersect.

This article positions Hughes's essay “Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan” as a continuation of the queer iconoclasm behind both Fire!! and the ethnographic material that eventually became “Spectacles in Color.”Footnote 7 In both “Spectacles” and “Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan,” Hughes examines queer subcultural practices within communities of color for whom homosexuality was considered antithetical to newly emerging definitions of progress (set forth by the black middle class and the Communist Party, respectively). By comparing the two pieces, we can observe Hughes's rhetorical resistance against anti-queer notions of progress within the black community manifest anew in his depiction of queer desire across the communist international. Such a comparison helps us to discern how Hughes forges a solidarity between black America and Soviet Central Asia built not on race or class identity, but on a common struggle for queer visibility within leftist politics.

The Trouble with Normal΄no

As a social phenomenon, “respectability politics” or “the politics of respectability” refers to a practice of assimilation wherein marginalized groups, in order to gain acceptance by mainstream society, shun members of their community whose behaviors or values do not conform to prevailing norms. The politics of respectability have had particular resonance for movements seeking to increase access and equality for LGBTQ and racial minorities, struggles that come together in “Spectacles of Color” and “Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan.” In The Trouble With Normal, queer theorist Michael Warner describes the logic of respectability politics as one of “trickle down acceptance,” wherein minority groups feel compelled to put forward their most normative and mainstream representatives in the hopes that the rights and regard afforded to them might “trickle down” and result in greater quality for the whole.Footnote 8 Warner refers specifically to what he sees as a normalizing shift within queer activism away from radical re-imaginings of kinship and towards a queer reinterpretation of the nuclear family, a phenomenon Lisa Duggan refers to as “homo-normativity.”Footnote 9

The feminist scholar Cathy Cohen, in a move to center the black experience within queer theory, provided an intersectional history of heterosexist respectability politics in her groundbreaking article “Deviance as Resistance.” The piece, a foundational text in black queer studies, notably appeared in the Du Bois Review; Cohen, drawing on Kevin Gaines's work on black leadership, argues that it was Du Bois's sociological study The Philadelphia Negro (1899) that provided much of the impetus for anti-queer progress narratives within the black community.Footnote 10 Written to dispel notions of racial inferiority, The Philadelphia Negro was focused on social (not biological) pathologies that sharpened the effects of discrimination. Cohen notes that Du Bois identified the nuclear family as key to black social progress, and believed that its absence, along with its “corresponding sexual mores,” furthered “systemic discrimination.”Footnote 11 Accordingly, Du Bois participated in a tendency common among assimilationist black leaders of the time: maintaining that homosexuality was something endemic to whites, not blacks.Footnote 12 This is evident in his reception of Fire!! whose themes of sexual transgression he sought to disentangle from discourses of black liberation. In an interview, Nugent, the author of “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” (and a close friend of Hughes's) recounted Du Bois's asking him, in regards to Fire!!, “Did you have to write about homosexuality? Couldn't you write about colored people?”Footnote 13

In The Trouble with Normal and his work since on queer negativity, Warner advocates for a revolutionary politics based on a “refusal to behave properly;” on forms of resistance that reject the “normal.”Footnote 14 In “Spectacles of Color” and “Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan,” we can see Hughes, by the very act of openly depicting queer desire alongside calls for racial equality and communism, enacting such a revolutionary program. In both pieces, Hughes firmly couches queer desire and cross-gender self-representation within larger debates about reform, social progress, and—in the case of Soviet Central Asia—revolution, therein inscribing sexual transgression into the very campaigns that insisted on its incompatibility.

Queer Harlem

“Spectacles in Color” is an impressionistic series of loosely connected vignettes, all featuring glittering scenes of Harlem life of the 1920s. Its opening paragraphs focus on the Hamilton drag ball, which Hughes describes as a “queerly assorted throng on the dance floor, males in flowing gowns and feathered headdresses and females in tuxedos and box-back suits (see Fig. 1).Footnote 15 The chapter abruptly shifts to a prolonged discussion of the poet Countee Cullen's wedding to Yolande Du Bois (Du Bois's daughter and only child), then pivots again to the ostentatious funeral of cabaret dancer Florence Mills, and then closes with the over the top church ceremonies of Harlem preacher Reverend Dr. George Wilson. It is the drag ball and the Cullen-Du Bois wedding, however, to which the most ink is devoted in what first seems like a rather strange juxtaposition. Samuel See, writing about the scenes that make up “Spectacles of Color,” ponders this strangeness, asking: “Why does Hughes initiate his discussion of Harlem cultural events . . . with a drag ball? What does the seemingly subcultural phenomenon of drag have in common with these more normative, indeed often heteronormative, ceremonies?”Footnote 16

Figure 1. Photograph of Langston Hughes by Carl Van Vechten, New York, March 29, 1932. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Reproduced with permission of the Carl Van Vechten Trust.

“Harlem loves spectacles of one kind or another,” Hughes writes, and indeed, the two spectacles in question: the drag ball and the wedding are arguably of “one kind.” The seeming clash of vignettes between Harlem's queer nighttime subculture and a high society hetero-function is rendered less strange by the realization that Cullen's homosexuality was Harlem's biggest open secret. Hughes's writes that the wedding “had Harlem talking for a long time,” a tongue in cheek nod to the scandal that ensued just months later when Cullen spent most of his European honeymoon with friend and lover Harold Jackman, sending Yolande into hysterics.Footnote 17 The sum effect of pairing the Cullen wedding scene with the opening drag ball description is the implication that Du Bois, as both black leader (and as father of the bride) was willfully blind to the changing sexual norms governing the Harlem Renaissance, which Henry Louis Gates insisted “was surely as gay as it was black.”Footnote 18

The queer underpinnings of “Spectacles of Color” and (its subtle mocking of Du Bois) aligned in many ways with Hughes's earlier participation in the editorial team behind the infamous literary journal Fire!!. During the summer of 1926, Hughes joined a group of young black writers looking to “burn up a lot of the old, dead conventional Negro-white ideas of the past.”Footnote 19 This group, who self-identified as “Niggerati” (a play on literati) consciously wrote against the respectability politics of the black establishment, choosing instead to depict black life as it was, in its full range (queer, uncouth, fiery) regardless of what conclusions white audiences might draw as a result.Footnote 20 Perhaps unsurprisingly then, the old guard of the black movement (namely Du Bois and the NAACP's flagship journal The Crisis) rejected Fire!!. Hughes writes of the blowback in The Big Sea, explaining: “None of the older Negro intellectuals would have anything to do with Fire!!. Dr. Du Bois in The Crisis roasted it. The Negro press called it all sorts of bad names, largely because of a green and purple story by Bruce Nugent, in the Oscar Wilde tradition, which we had included.”Footnote 21 The “green and purple” story Hughes was referring to was Nugent's “Smoke, Jade and Lilies,” whose uncensored depiction of black queer desire attracted much of the ire directed towards the magazine.Footnote 22

The fallout from Fire!!, coupled with the events depicted in “Spectacles of Color,” suggest that by the time Hughes arrived in the Soviet Union in the early 1930s, questions of anti-queer respectability politics were not only present in his mind, but pressing. Perhaps this is why, amidst the pervasively masculine ethos of Soviet culture, Hughes chose to write about the bachi, the boy dancers of Central Asia, and their “wigs with girlish curls.”Footnote 23

Queer Tashkent

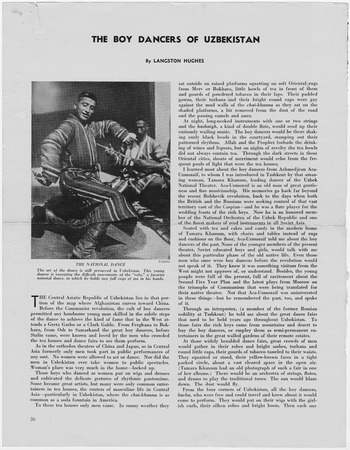

Hughes arrived in Moscow in 1932 as a part of a group of twenty-two African-Americans who had been hired by the Soviet film studio Mezhrabpom to star in “Black and White,” a film about race relations and labor disputes in the American South.Footnote 24 When plans for the movie fell through, Hughes decided to prolong his stay, with plans to write a series of articles and eventually a book about “the colored peoples of the Soviet Union.”Footnote 25 He spent the next several months in Central Asia, primarily in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Most of what we know about Hughes's time there comes from his 1956 autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander, his anthropological study of Central Asia, A Negro Looks at Soviet Central Asia (1934), and a series of articles published in various American magazines and newspapers (see Fig. 2).Footnote 26 While most of Hughes's Soviet writings express enthusiasm for the Bolshevik project and the potential for communism to quell racial tensions, “Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan” belies a certain anxiety about the consequences of Sovietization, particularly in regards to the regulation of sex in Central Asia.Footnote 27

Figure 2. First page of “Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan” in Travel magazine. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Reproduced with permission of the Langston Hughes Estate and Sovfoto.

“Boy Dancers” is ostensibly about the progress that the Soviet Union has made in regards to the purported liberation of Muslim women, a topic he also wrote about in “In an Emir's Harem” for Woman's Home Companion.Footnote 28 In “Boy Dancers,” Muslim women, now free under Soviet rule to appear in public, have replaced the bachi from the tea houses of Central Asia which, Hughes writes, “[are] as common as the soda fountain in America.”Footnote 29 However, for a piece that is meant to celebrate the entrance of women into the teahouse dancing tradition, the article centers the queer figure of the bachi and waxes mournfully about the supposed end of the practice.

Furthermore, the language Hughes employs to describe the bachi would seem designed to titillate rather than to condemn. Writing about “Boy Dancers of Uzbekistan,” Kate Baldwin takes note of this, commenting: “The widely enforced unspeakability of the old practice is undermined by Hughes's artful description of it.”Footnote 30 Indeed, in one passage, Hughes describes in great detail the movements of the dancers, belying a fascination that undoes whatever enthusiasm Hughes claims to have for the new reforms that have resulted in the bachi's banishment:

They put on their wigs with the girlish curls, their silken robes, and bright boots. Then each one in turn would begin to circle to the music in the vast outdoor space, recreating in his own way the patterned movements, the delicate turning of the head and wrists that characterize the Uzbek dance. The huge male audience would shout their approval as each especially beautiful traditional movement revealed itself anew expertly developed by the boy in the dusty ring.Footnote 31

Baldwin argues that the evocative, and thus seemingly sympathetic, language that Hughes employs to describe the bachi, is his attempt to adopt a non-western (non-American) subject position; Baldwin writes: “Like the non-Western attitude with which his words imply sympathy here, Hughes's prose clearly delights in this age-old tradition of boy dancers.”Footnote 32

I would argue however, that Hughes's sympathy for the bachi is not necessarily voiced through anti-western positionality, but instead, harkens back to his queer alliance with the Niggerati against Du Bois's black respectability politics. Such an interpretation is not without precedent, as in much of Hughes's writing from Central Asia he explicitly imposes American social debates into the Soviet context, at one point describing segregated trains in tsarist Russia as “Jim Crow trolleys.”Footnote 33 Accordingly, I posit that rather than signaling that Hughes identifies with non-western perspectives, Hughes's positive depiction of the bachi tradition is more closely aligned with the impulses behind Fire!! and Hughes's own advocacy for queer visibility in black American discourses of progress.Footnote 34 And indeed, when Hughes talks about the phasing out of the bachi tradition in Central Asia, he is quick to couch it within larger discourses of progress and the mainstreaming of Central Asian cultures into Soviet society, writing:

None of the younger members of the present theater, Soviet educated boys and girls, would talk with me about this particular phase of old native life. Even those men who were once boy dancers before the revolution would not speak of it . . . besides, the young people were full of the present, full of excitement about the Second Five-Year Plan and the latest plays from Moscow on the triumphs of communism.Footnote 35

That Hughes positions the bachi tradition as being in contention with narratives of progress and futurity recalls Du Bois yet again. Du Bois critiqued homosexuality in the black community largely on the grounds that it was reminiscent of “primitive” behavior.Footnote 36 Du Bois, like the Soviets in Central Asia (as presented by Hughes), locates queer desire firmly in the backwards, undeveloped past.

In Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia, Dan Healey writes about the phenomenon of defining the boy dancer tradition as backwards and inherently in tension with Russian-produced Soviet discourses of progress. Healey explains that this practice emerged from a necessity to define the heterosexual cisgender Russian male as the embodiment of revolutionary devotion.Footnote 37 It also served to justify the imposition of a Russian-centered ideology of modernization onto the supposedly backwards peripheries of the new Soviet empire. Healey writes:

Femininity in men was a marker of backwardness, imagined not in the Russian homosexual but in the “unfortunate bachi of Turkestan,” boys of “an utterly clearly defined masculine sex” who “were dressed in feminine clothes and spooled forever” by sexual and economic exploitation. Male femininity could only be imagined as foreign, backward, and tragic, while masculinization in women endowed them with competence, authority, and crucially, loyalty to the modernizing (and implicitly Russian) values of the Revolution.Footnote 38

As Healey argues, Soviet policies aimed at “modernizing” Central Asia on the level of sexuality included an intense policing of queer practices, a concerted effort to frame homosexuality a primitive vestige of the past, and the racialization of queer desire as eastern (and thus non-Russian). It was this constellation of pressures that Hughes stumbled upon when he arrived in Uzbekistan in 1932, the product of which resulted in a context not identical to Harlem, but similar enough to evoke an analogous response.

Hughes's “artful depiction” of the bachi is a form of resistance to global discourses of progress that deny visibility to queer practices, something that connected members of the communist international from New York to Tashkent. As was the case in “Spectacles of Color” and Fire!!, Hughes's essay on the boy dancers of Uzbekistan centers same-sex desire within revolutionary discourses, thereby rejecting on the world stage the politics of respectability that plagued him at home in Harlem. Taken together, these two pieces of Hughes's writing, which find resonances between the African-American and Uzbek experiences, gesture not only towards an ethnic transnational awakened by Soviet internationalism, but to a translocal queer collective whose revolt was its own revolution.