Esketamine was approved for use in ‘treatment-resistant depression’ in the USA, Europe and the UK in 2019. Some commentators have ‘cautiously welcomed’ esketamine,Reference Jauhar and Morrison1 whereas others have praised its novel mode of action.Reference Devlin2 The UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issued draft guidance in January 2020 recommending that esketamine not be used for treatment-resistant depression owing to a lack of evidence of clinical and cost-effectiveness. We here briefly review the evidence for esketamine's effectiveness and safety in trials submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulators.

Ketamine as an anaesthetic agent

Ketamine has been licensed for use as an anaesthetic agent for five decades and it is favoured for use in emergencies, because it rapidly induces a trance-like state (often called dissociation) associated with pain relief, sedation and memory loss.Reference Morgan and Curran3 However, as patients often report a variety of unusual symptoms when recovering from ketamine anaesthesia, including delusions, hallucinations, delirium and confusion, and sometimes ‘out of body’ or ‘near death’ experiences,Reference Morgan and Curran3 it was withdrawn from mainstream anaesthesia and restricted for specialist purposes (including veterinary practice and paediatrics).

Ketamine commonly elevates blood pressure and heart rate,Reference Suleiman, Ik and Bo4 which has been associated with fatal heart failure and myocardial infarction,Reference Suleiman, Ik and Bo4 as well as stroke and cerebral haemorrhageReference Morgan and Curran3 more often in those with pre-existing risk factors.

Ketamine as a recreational drug

Ketamine has also been used recreationally from the 1970s, with nicknames ‘special K’, ‘new ecstasy’ and ‘psychedelic heroin’. At subanaesthetic doses ketamine produces a dissociative state that some users enjoy, characterised by a sense of detachment from one's physical body and the external world, often referred to as the ‘K-hole’ by recreational users.Reference Morgan and Curran3 It is usually ingested through insufflation (snorting).Reference Morgan and Curran3 A usual recreational dose is between 60 and 250 mg of ketamine.5

Recreational use of ketamine has climbed rapidly in recent years, especially among young people: a crime survey in England and Wales reported that 3.1% of 16- to 24-year-olds used the drug in 2017–2018.6 Between 1993 and 2016 there were at least 117 deaths in England and Wales attributed to the drug,Reference Handley, Ramsey and Flanagan7 with a tenfold increase from 1999 to 2008,Reference Morgan and Curran3 but reliable figures are not available because ketamine is not routinely tested in all cases of unexplained deaths.Reference Morgan and Curran3

Deaths from ketamine include accidental poisonings, drownings, traffic accidents and suicide.Reference Schifano, Corkery, Oyefeso, Tonia and Ghodse8,Reference Cheng, Chan and Mok9 As a dissociative anaesthetic, ketamine can reduce awareness of the environment, increasing risk of accidental harm.Reference Morgan and Curran3 It impairs hand–eye coordination and balance, putting people at increased risk of driving accidents.Reference Morgan and Curran3 In Hong Kong, where it achieved particular popularity, ketamine had been used by 9% of individuals involved in fatal traffic accidents between 1996 and 2000.Reference Cheng, Chan and Mok9

Ketamine also induces ulcerative cystitis, found in 30% of regular UK ketamine users and known as ‘ketamine bladder’.Reference Morgan and Curran3 The condition can lead to difficulty passing urine, hydronephrosis and kidney failure.Reference Morgan and Curran3 Regular ketamine use also causes cognitive impairment, in particular difficulty with working memory.Reference Morgan, Muetzelfeldt and Curran10 Increased depression scores have been found in both daily users and ex-users in a longitudinal study, although not more infrequent users.Reference Morgan, Muetzelfeldt and Curran10

Ketamine is also addictive.Reference Morgan and Curran3,Reference Chen, Huang and Lin11 It quickly induces toleranceReference Morgan and Curran3 and stopping regular use causes a withdrawal syndrome characterised by anxiety, dysphoria and depression, shaking, sweating and palpitations, and craving the drug.Reference Morgan and Curran3,Reference Chen, Huang and Lin11 Frequent users report using the drug compulsively until supplies run out.Reference Morgan and Curran3 Ketamine has a complex array of actions on many neurochemical systems, including blockade of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. The mechanism through which it produces its psychoactive and addictive effects is not completely clear.Reference Sleigh, Harvey, Voss and Denny12

Ketamine as a ‘fast-acting’ antidepressant

Intravenous ketamine was demonstrated to improve depression scores in the 2000s,Reference Zanos, Moaddel, Morris, Riggs, Highland and Georgiou13,Reference Malhi, Byrow, Cassidy, Cipriani, Demyttenaere and Frye14 with a trial showing ‘rapid-onset antidepressant effects’ in as little as 2 h.Reference Zanos, Moaddel, Morris, Riggs, Highland and Georgiou13 It would seem difficult to distinguish this ‘rapid-onset antidepressant effect’ from the ‘high’ or altered state known to be induced by ketamine, however. Although some commentators claim that it leads to a genuine, long-lasting antidepressant effect,Reference Atigari and Healy15 this has not been established in randomised trials, as emphasised in expert guidance.16 As ketamine was already licensed for use, Janssen applied for licensing of one of its enantiomers, (S)-ketamine, delivered by insufflation (via a nasal spray). (S)-ketamine, or esketamine, is twice as potent as ketamine.Reference Zanos, Moaddel, Morris, Riggs, Highland and Georgiou13

Evidence submitted to the FDA

Five studies were submitted by Janssen to the FDA to seek approval of esketamine for adjunctive treatment of ‘treatment-resistant depression’: three efficacy trials, each lasting 4 weeks, one discontinuation trial, and one safety trial lasting 60 weeks. In the 4-week and discontinuation trials, doses ranged from 56 to 84 mg, in line with recreational doses of ketamine, and were administered twice a week, via insufflation.

Although ‘treatment-resistant depression’ sounds rare and severe, Janssen's definition, consisting of people who have ‘failed’ two different antidepressants, is likely to encompass many current antidepressant users.Reference Malhi, Das, Mannie and Irwin17

The FDA normally requires two positive efficacy trials in order to license a drug, ‘each convincing on its own’.Reference Turner18 This requirement has been criticised because short-term trials do not accurately reflect the long periods many drugs are eventually used for in practiceReference Cristea and Naudet19 and they discount negative trials. However, esketamine did not meet even this standard. Out of the three short-term trials conducted by Janssen only one showed a statistically significant difference between esketamine and placebo.Reference Fedgchin, Trivedi, Daly, Melkote, Lane and Lim20,21 These were even shorter than the 6–8 week trials the FDA usually requires for drug licensing.

The single positive efficacy trial

The only positive study found a difference of 4 points on the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) favouring esketamine over placebo.Reference Popova, Daly, Trivedi, Cooper, Lane and Lim22 The MADRS scale goes from 0 to 60; the average score for participants at baseline was 37. The response to placebo treatment (a nasal spray with an embittering agent) was a 15.8-point reduction in the MADRS score. The response to esketamine was a reduction of 19.8 points.21 A reduction of 7–9 points on the MADRS has been found to correspond to a clinically noticeable (‘minimally improved’) change on the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI);Reference Leucht, Fennema, Engel, Kaspers-Janssen, Lepping and Szegedi23 ‘much improved’ requires a reduction of 16–17 points. A 4-point difference therefore corresponds to less than ‘minimal’ change and is one-quarter the size of the placebo response, suggesting doubtful clinical relevance.Reference Turner18 Furthermore, participants would have been unmasked (‘unblinded’) by the noticeable psychoactive effects of esketamine (dissociation was reported by the majority of participants); expectation effects might therefore inflate the apparent difference between placebo and esketamine.

The discontinuation trial

As Janssen could not provide two positive efficacy trials, the FDA loosened its rules and allowed a discontinuation trial to provide evidence of efficacy.Reference Turner18 This trial randomly allocated patients who demonstrated ‘stable remission’ following a 16-week esketamine treatment (a highly selected group of participants) to either continue or stop esketamine, and measured subsequent relapse.Reference Daly, Trivedi, Janik, Li, Zhang and Li24

This study design is problematic because withdrawal effects from the drug can be mistaken for relapse of depression. Ketamine is recognised to have withdrawal effects, including lowered mood (dysphoria), fatigue, poor appetite and anxiety.Reference Chen, Huang and Lin11 Although the study report suggests that there was no evidence of a withdrawal syndrome on the Physician Withdrawal Checklist, scores for the different groups are not reported and it is not clear how items in the checklist such as ‘insomnia’, ‘anxiety–nervousness’, ‘dysphoric mood–depression’, ‘difficulty concentrating, remembering’, ‘fatigue’ and ‘lack of appetite’ were distinguished from almost identical items in the MADRS (‘apparent sadness’, ‘reported sadness’, ‘inner tension’ ‘reduced sleep’, ‘reduced appetite’, ‘concentration difficulties’, ‘lassitude’).

As half (48.7%) of relapses occurred in the first 4 weeks following esketamine cessation, the time most likely for withdrawal effects to occur, and as the relapse rate in the placebo group became ‘closer to esketamine with each week’, as highlighted by the FDA, confounding of ‘relapse’ by withdrawal seems likely.21 Further evidence of a withdrawal effect is also suggested by the marked ‘relapse prevention’ effect of a drug with minimal antidepressant effects in the short term. This pattern is similar to what might be seen in a trial of a benzodiazepine for anxiety: modest effects in the short term, but marked ‘relapse prevention’ effects on discontinuation, if confounding by withdrawal effects are ignored.

The FDA also highlighted another problem with this study design: ‘unblinding’,21 as in the acute efficacy studies. The absence of esketamine's psychoactive effects would be noticed by participants randomised to placebo and consequent negative expectations would tend to increase their chance of relapse.21 Higher dissociation scores while on treatment were correlated with shorter time to relapse, consistent with this hypothesis.

Importantly, the FDA also raised the concern that the positive results of this study were driven by a single site in Poland. At this site there was a 100% relapse rate in the placebo arm (n = 16 participants), compared with a 33% relapse rate in this arm in all other sites (n = 81 participants).21 It has been demonstrated that if this outlier site is excluded there is no difference between esketamine and placebo (the P-value changes from 0.012 to 0.48),Reference Turner18 leading to the conclusion that the findings are ‘not robust’.

The safety of esketamine in trials submitted to the FDA

When licensing esketamine, the FDA recommended a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) because of concerns about sedation, dissociation and diversion. This requires the drug to be administered in a healthcare setting, and for patients to be monitored for resolution of sedation, dissociation and changes in vital signs for at least 2 h. There were, however, some concerning safety signals that many commentators felt were not adequately addressed by these measures.

In the Janssen licensing trials there were six deaths,21 all occurring in the participants who were assigned to esketamine. Three were suicides (Table 1).

Table 1 Deaths reported in esketamine trialsa

a. These data are derived from the Food and Drug Administration review of data submitted by Janssen.Reference Kim and Chen30

b. Total number of participants exposed in Stage 2 and Stage 3 trials up to 4 September 2018.Reference Kim and Chen30

One death was a motorcycle accident 26 h after esketamine administration.21 One death was a myocardial infarction, 6 days after esketamine.21 The third death was due to acute heart and lung failure 5 days after esketamine, in an individual with risk factors. These causes of death have been observed previously in ketamine use: blood pressure spikes cause heart failure and myocardial infarction in patients at risk; impairment of hand–eye coordination and its dissociative effects increase the risk of motor vehicle accidents.Reference Morgan and Curran3,Reference Suleiman, Ik and Bo4,Reference Schifano, Corkery, Oyefeso, Tonia and Ghodse8,Reference Cheng, Chan and Mok9 However, the FDA argued that one participant's cardiovascular parameters had been normal before and after their last administration of esketamine, and in the other that esketamine produces only short-lasting blood pressure rises, concluding that ‘it is difficult to consider these deaths as drug-related’.21 In addition to the deaths, one participant on esketamine experienced a non-fatal cerebral haemorrhage,Reference Cristea and Naudet19 also recognised as a risk in ketamine use owing to its blood pressure spikes,Reference Morgan and Curran3 and five further participants in the esketamine arms had non-fatal motor vehicle accidents.25

The three suicides occurred 4, 12 and 20 days after the last dose of esketamine.Reference Schatzberg26 The FDA attributed these deaths to ‘the severity of the patients’ underlying illness’.21 However, two of the participants who died by suicide showed no previous signs of suicidal ideas during the study, either at entry to the study or at the last visit (data were not available for the third participant).21 The FDA accepted Janssen's assessment that the suicides were not ‘drug-related’.21

However, others have argued that these cases might fit with a pattern of a severe withdrawal reaction, consistent with other reports of suicide associated with recreational ketamine,Reference Schifano, Corkery, Oyefeso, Tonia and Ghodse8,Reference Cheng, Chan and Mok9 and are significant enough in number to constitute a worrying signal.Reference Schatzberg26

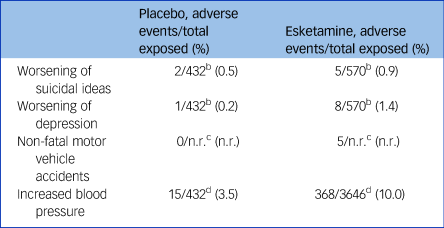

An increase in depression and suicidality was also observed during esketamine treatment, compared with placebo (Table 2). In the short-term trials, six participants (1.4% of the total) in the esketamine group became more depressed, compared with only one on placebo (0.2%); five participants expressed increased suicidal ideas in the esketamine group (0.9%), compared with two on placebo (0.5%).21 The drug will be marketed with a ‘black box’ warning including a risk of suicidal ideas and behaviour,Reference Cristea and Naudet19 but it is not clear whether this measure is stringent enough.

Table 2 Selected adverse events reported in esketamine trialsa

n.r., not reported.

a. These data are derived from the submission by Janssen25 and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review of the data.Reference Kim and Chen30 However, the FDAReference Kim and Chen30 noted that there was misclassification, underreporting and misrepresentation of the adverse events, so that the presented data likely represent an underestimation of the incidence of adverse events. Differing dosages of esketamine have been combined for simplicity.

b. Total number of participants exposed in trials 3001, 3002, 3005 (4-week efficacy trials) and trial 3003 (discontinuation trial).Reference Kim and Chen30

c. Reported in Janssen submission to FDA without relevant sample size.25

d. Total number of participants in completed Stage 3 studies.25

Potentially paradoxically, Janssen is seeking an expansion of the indications for use of esketamine to include acutely suicidal patients (on the basis of two studies that showed a reduction of suicidality on a subscale of the MADRS at 24 h, but no effect on the pre-specified measure of suicidality, the CGI Severity of Suicidality (Revised)).Reference Jancin27

A large range of other side-effects occurred: half of participants experienced dissociation and one-third dizziness; increased blood pressure, vertigo, hypoaesthesia, nausea and sedation were each present in between 10 and 30% of participants (Table 3).21

Table 3 Most common adverse events from esketamine compared with placeboa

a. Data from the 4-week studies 3001 and 3002.Reference Kim and Chen30 Differing dosages of esketamine have been combined for simplicity.

A significant number of participants on esketamine developed signs of bladder irritation, reminiscent of ‘ketamine bladder’: urinary tract infections, pain, discomfort, cystitis and nocturia.21 In the 60-week study, with weekly or fortnightly esketamine administration (less frequent than the short-term trials), a fifth of participants reported bladder effects. Some cognitive impairment was detected in the long-term study among older participants. The FDA, however, argued that the lack of a comparison arm and individual variability made it difficult to conclude that these effects were attributable to esketamine, even though they are well-known consequences of ketamine use.21

MHRA and NICE reviews of esketamine

The UK's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has decided, on the basis of its review of this evidence, to license esketamine for use in treatment-resistant depression. This decision was made just months after Public Health England (PHE) presented its report about ‘prescribed drug dependence’ in the UK. The PHE report found that one in four Britons are using at least one drug out of the drug classes of opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, Z-drugs and antidepressants.Reference Taylor, Annand, Burkinshaw, Greaves, Kelleher and Knight28

Many of these classes of drug were introduced into clinical practice as ‘safe’ and approved for use on the basis of short-term studies in the absence of long-term safety data, including data on dependence and withdrawal. The PHE report comments:

‘Recurring patterns are evident in the history of medicines that may cause dependence or withdrawal. New medicines are seen as an important part of the solution to a condition, resulting in widespread use. Their dependence or withdrawal potential are either unknown at this point, due to a lack of research, or perhaps downplayed. As evidence of harm from dependence or withdrawal emerges, efforts are made to curtail prescribing. The repetition of this pattern is striking.’Reference Taylor, Annand, Burkinshaw, Greaves, Kelleher and Knight28

NICE released draft guidance recommending that esketamine should not be used for ‘treatment-resistant depression’ in January 2020.Reference Mahase29 Their rationale for this decision included a lack of evidence that esketamine was more effective than existing treatments for ‘treatment-resistant depression’, including psychological treatment, as well as highlighting the lack of long-term evidence of efficacy or meaningful end-points such as quality-of-life measures. NICE also emphasised that esketamine is ‘unlikely’ to be cost-effective. However, the NICE appraisal did not question the published interpretation of the efficacy data and lacked focus on the harms of treatment, including suicides, which might be more marked in real-life, longer-term use. As esketamine has been licensed by the MHRA it remains available for prescription ‘off-label’ in the UK.

It would seem that themes from history are repeating: a known drug of misuse, associated with significant harm, is increasingly promoted despite scant evidence of efficacy and without adequate long-term safety studies. We hope that NICE maintains its sensible position on requiring further evidence of efficacy, as well as paying adequate attention to the harms of esketamine, and calls for long-term efficacy and robust safety trials instead of setting patients up as unwitting guinea pigs in another unregulated pharmaceutical experiment.

Author contributions

M.A.H. and J.M. conceived the idea of the article, M.A.H. wrote the article and J.M. edited the article and supervised the process.

Declaration of interest

J.M. is co-chairperson of the Critical Psychiatry Network.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.89.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.