Methamphetamine use is a major public health concern worldwide. Between 13% and 53% of people who use methamphetamine report psychotic symptoms, and this rate is higher among those with methamphetamine dependence.Reference Ma, Li, Wang, Li, Meng and Blow1–Reference Sulaiman, Said, Habil, Rashid, Siddiq and Guan4 Methamphetamine users also have an increased risk of developing schizophrenia.Reference Callaghan, Cunningham, Allebeck, Arenovich, Sajeev and Remington5 Three prospective studies have shown methamphetamine use predicts psychotic symptoms, but research is yet to determine if the reverse also applies (that psychotic symptoms also predict methamphetamine use).Reference Ma, Li, Wang, Li, Meng and Blow1,Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6,Reference McKetin, Dawe, Burns, Hides, Kavanagh and Teesson7 This is important, as the direction of the relationship between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms has clinical implications for how we understand and treat psychotic symptoms in methamphetamine users.

This 12-month prospective study aimed to determine if the relationship between methamphetamine use and positive psychotic symptoms (hereafter ‘psychotic symptoms’) is bidirectional. The impact of methamphetamine dependence and psychotic disorders (including primary versus substance-induced psychotic disorders) on these relationships was also examined.

Method

Participants and procedure

Methamphetamine users were recruited after collecting injecting equipment from free needle and syringe programmes in three Australian cities (Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney). Participants were required to have used methamphetamine regularly (at least monthly) in the last 6 months, to identify methamphetamine as their main drug of use, be at least 18 years of age and understand English. The baseline and 11 monthly follow-up interviews were conducted face-to-face in a location convenient to the participant. The interview was delayed if the participant had used methamphetamine in the previous 12 h to reduce the chance of results being affected by acute methamphetamine intoxication. Telephone interviews were conducted if face-to-face interviews were not practicable. The interviewers were trained researchers with at least honours degrees in psychology. Participants completed a mean of 9.14 (s.d. = 3.16) of the 11 follow-up interviews with the majority completing 10 (n = 42, 20.9%) or all 11 (n = 104, 51.7%) follow-ups. They received $10 (Australian dollars) for completing each interview.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee – approval: PSY/36/04/HREC. All adult participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study. See Hides et al Reference Hides, Dawe, McKetin, Kavanagh, Young and Teesson8 for further information.

Measures

Structured diagnostic interview

The Psychiatric Research Interview for DSM-IV Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM-IV, Version 6)Reference Hasin, Trautman, Miele, Samet, Smith and Endicott9 was administered at baseline to provide lifetime and current DSM-IV diagnoses of a substance-induced psychotic disorder and a primary psychotic disorder. The PRISM reliably differentiates between primary and substance-induced psychotic disorders (kappa (κ) = 0.70–0.83).Reference Torrens, Serrano, Astais, Pérez-Domínguez and Martín-Santos10 The major depressive and manic episode modules of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Version 5)Reference Lecrubier, Sheehan, Weiller, Amorim, Bonara and Sheehan11 were also administered. The researchers were trained in the use of the PRISM by L.H., an accredited user. Participants were also asked if they had a personal and family history of psychosis.

Substance use

Timeline Followback (TLFB) interviews were used to obtain precise information on the frequency of methamphetamine (including amphetamines, ice, speed), cannabis, alcohol and heroin use in the previous 4 weeks using calendar-based cues.Reference Fals Steward, O'Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin and Rutigliano12 Only TLFB data in the past 2 weeks was used in this study. TLFB has high test–retest reliability for past 30 day alcohol, cannabis and methamphetamine (intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) = 0.77–0.94), convergent and discriminant validity with other self-report measures, collateral data and biological measures.Reference Fals Steward, O'Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin and Rutigliano12 Compared with urinalysis, the TLFB has 88% sensitivity and 96% specificity for methamphetamine use.Reference Fals Steward, O'Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin and Rutigliano12 Other drug use in the past 4 weeks including tobacco, cocaine, inhalants and ecstasy use was assessed on a yes/no response scale. Methamphetamine dependence in the past year was assessed using the Severity of Dependence Scale.Reference Topp and Mattick13 A cut-off score of ≥4 has optimal sensitivity (71%) and specificity (77%) for detecting a DSM-III-R diagnosis of severe methamphetamine dependence on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.Reference Topp and Mattick13

Psychiatric symptoms

The 24-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was used to assess the severity of psychiatric symptoms in the previous 2 weeks.Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Gutkind and Gilbert14 Each symptom is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1, not present; 2, very mild; 3, mild; 4, moderate; 5, moderately severe; 6, severe; 7, extremely severe).Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Gutkind and Gilbert14 A symptom score of ≥4 is considered clinically significant.Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Gutkind and Gilbert14 A meta-analysis of the factor structure of the BPRS (24 studies, n = 10 084) found four subscales (affect, positive and negative symptoms, activation).Reference Dazzi, Shafer and Lauriola15 The four-item positive symptom subscale (hallucinations, suspiciousness, unusual thought content, grandiosity) total score (range: 4–28) was the primary outcome measure in this study.Reference Ventura, Nuechterlein, Subotnik, Gutkind and Gilbert14 Secondary analyses using a three-item psychotic symptom total (hallucinations, suspiciousness, unusual thought content; range: 3–21) were also conducted to replicate previous research on methamphetamine-related psychosis and evaluate the robustness of our conclusions.

Out of the 2019 interviews conducted over the 12-month study, 142 (7.03%) were rated for interrater reliability purposes. These interviews were conducted semi-randomly during site visits by the project manager. The ICC for the BPRS positive symptom subscale and total scores were 0.97 and 0.98, respectively. The reliability of telephone-delivered BPRS interviews has been established.Reference Hides, Dawe, Kavanagh and Young16

Data analysis

Two linear mixed-effect models were first used to examine the lagged effect of (a) psychotic symptoms on methamphetamine use in the next wave and (b) methamphetamine use on psychotic symptoms in the next wave, adjusting for type of lifetime psychotic disorder (none, substance-induced psychotic disorder, primary psychotic disorder), methamphetamine dependence at baseline, age, gender, birth country, family history of psychosis and previous-wave cannabis, alcohol and heroin use (days of use in past 2 weeks on the TLFB). A random intercept for each individual was specified so that the error component of each model was broken down into within- and between-individual variations to account for the repeated measure design, and to adjust the standard error of the model parameters (beta coefficients).Reference Allison, Williams and Moral-Benito17 Given the strong skewness in both psychotic symptoms and methamphetamine use, both variables were log-transformed. The variables were then standardised to allow comparisons in effect size between models. Mixed-effect negative binomial models were run as supplementary analyses to check the consistency of results. We also explored if the lagged effects varied among participants with different types of lifetime psychotic disorders and methamphetamine dependence at baseline by including relevant interactions.

Cross-lagged panel models with fixed effects were then used to examine the bidirectional effect between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms (see Fig. 1).Reference Allison, Williams and Moral-Benito17 This type of model is based on dynamic panel data models that estimate the causal parameters in bidirectional associations by simultaneously estimating the effect: (a) of methamphetamine use in the previous wave on psychotic symptoms in the next wave, and (b) of psychotic symptoms in the previous wave on methamphetamine use in the next wave.Reference Allison, Williams and Moral-Benito17,Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman18 These models adjust for the associations between the same variables over time and measured/unmeasured time-invariant confounders using a fixed-effect term for individuals.Reference Allison, Williams and Moral-Benito17,Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman18 Effects of age, gender, birth country, lifetime psychotic disorder and methamphetamine dependence at baseline were also adjusted for. Because of the complexity of the model, we recoded ‘lifetime psychotic disorder’ into ‘present/absent’. Similar to previous analysis, methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms were first log-transformed and then standardised. The following key equations were simultaneously estimated:

$${\rm Methamphetamine\ us}{\rm e}_{it} = \mu _t + \beta _1\;{\rm psychotic\ symptom}{\rm s}_{it-1} + \beta _2\;{\rm methamphetamine\ us}{\rm e}_{it-1} + \gamma _1z_i + \alpha _i + {\`{o}} _{it}$$

$${\rm Methamphetamine\ us}{\rm e}_{it} = \mu _t + \beta _1\;{\rm psychotic\ symptom}{\rm s}_{it-1} + \beta _2\;{\rm methamphetamine\ us}{\rm e}_{it-1} + \gamma _1z_i + \alpha _i + {\`{o}} _{it}$$ $${\rm Psychotic\ symptom}{\rm s}_{it} = \tau _t + \beta _3\;{\rm psychotic\ symptom}{\rm s}_{it-1} + \beta _4\;{\rm methamphetamine\ us}{\rm e}_{it-1} + \gamma _2z_i + \eta _i + \upsilon _{it}$$

$${\rm Psychotic\ symptom}{\rm s}_{it} = \tau _t + \beta _3\;{\rm psychotic\ symptom}{\rm s}_{it-1} + \beta _4\;{\rm methamphetamine\ us}{\rm e}_{it-1} + \gamma _2z_i + \eta _i + \upsilon _{it}$$

Fig. 1 Simplified schematic for the cross-lag model with fixed effects.

a. Covariates include gender, age, not Australian born, lifetime psychotic disorder, baseline methamphetamine dependence.

Subscripts i and t were used to denote measurement for participants i and time t, while α i and η i were the fixed-effect term for participant i and represented the combined effect of unmeasured time-invariant variables on amphetamine use and psychotic symptoms respectively. The terms μ t and τ t were the intercepts that varied with time, and the terms òit and υit were the residuals and z i was a vector of the covariates.

The coefficients represented the lagged effect of psychotic symptoms on methamphetamine use and the lagged effect of methamphetamine use on psychotic symptoms, and represented the autocorrelations of methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms, respectively. The cross-sectional association between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms was also estimated and adjusted for. The model was estimated in Mplus 7.3.Reference Muthén and Muthén19 Three model fit indices, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), were used to evaluate the model fit.Reference Hu and Bentler20 For CFI, SRMR and RMSEA, a value close to zero indicates good model fit. Based on previous simulation study,Reference Hu and Bentler20 a model with CFI≥0.95, SRMR≤0.09 and RMSEA≤0.06 was considered to fit the data well. The full sample was used in the cross-lagged model (n = 201), as any missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics at baseline. Most participants (n = 201) were men and born in Australia. Around half of them had methamphetamine dependence or a lifetime psychotic disorder at baseline. Only 11 (6%) participants had ever taken antipsychotic medication. They all identified as primary methamphetamine users, but cannabis was the most frequently used drug, followed by methamphetamine and alcohol (see Table 1). Participants had been using methamphetamine for a mean of 12.18 years (s.d. = 7.46) at baseline and most (86%, n = 172/201) had injected methamphetamine in their lifetime, 77% (n = 136/177) at 1-month follow-up. The mean level of psychotic symptom severity was low, but 28% (n = 57) had at least one clinically significant psychotic symptom (BPRS score of ≥4) on the psychotic symptom subscale (n = 52, 26% on the three-item measure).

Table 1 Baseline demographic, substance use and psychosis characteristics of regular methamphetamine users (n = 201)

a. Missing for one participant.

b. Missing in two participants.

c. Missing in four participants.

d. Missing in five participants.

There was significant decrease in the frequency of methamphetamine use and the severity of psychotic symptoms between baseline and the 11-month follow-up (P<0.001; see supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.263). The effect size was moderate (d = 0.55) for methamphetamine use and small (d = 0.20) for psychotic symptoms. There was no significant difference in the frequency of cannabis (mean 5.50, s.d. = 5.77; (b = 0.24, 95% CI −0.41 to 0.90) or alcohol (mean 3.82, s.d. = 4.62; b = −0.59, 95% CI −1.33 to 0.16) use between baseline and the 11-month follow-up. In total, 14% (n = 22/153) of participants had a clinically significant psychotic symptom at the 11-month follow-up on the four-item BPRS psychotic symptom subscale (14%, n = 21/153, on the three-item subscale).

Prospective relationship between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms

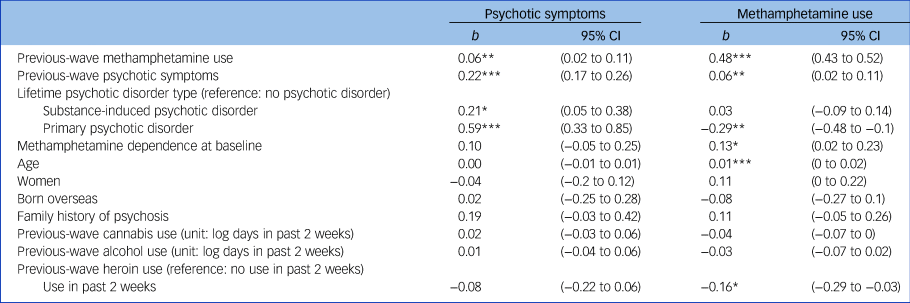

Table 2 shows the results from the two mixed models. In the first model, previous-wave methamphetamine use significantly predicted the psychotic symptom score in the next wave after adjusting for a range of covariates, b = 0.06, s.e. = 0.02, P = 0.006 (unadjusted b = 0.09, s.e. = 0.02, P<0.001). In the second model, previous-wave psychotic symptom score significantly predicted methamphetamine in the next wave, b = 0.06, s.e. = 0.02, P = 0.005 (unadjusted b = 0.13, s.e. = 0.02, P<0.001). A family history of psychosis, and previous-wave cannabis and alcohol use were not significantly associated with psychotic symptoms and methamphetamine use in the next wave. Previous-wave heroin use was associated with reduced methamphetamine use in next wave, b = –0.16, s.e. = 0.07, P = 0.014. However, key model estimates, including the coefficient for previous-wave psychotic symptoms and methamphetamine use, with and without heroin use were nearly identical. Therefore, these four variables were removed from the subsequent cross-lagged analysis to reduce model complexity.

Table 2 Results from linear mixed-effect regressions predicting methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms among regular methamphetamine users

***P<0.001; **P<0.01; *P<0.05.

Results from the supplementary analyses using mixed-effect negative binomial models yielded similar conclusions (see supplementary Table 2). Non-significant effects were found from the interactions of (a) previous-wave methamphetamine use and lifetime psychotic disorder type in predicting psychotic symptoms, (b) previous-wave psychotic symptoms and lifetime psychotic disorder type in predicting methamphetamine use (see supplementary Table 3), (c) previous-wave methamphetamine use and baseline methamphetamine dependence in predicting psychotic symptoms, and (d) previous-wave psychotic symptoms and baseline methamphetamine dependence in predicting methamphetamine use (see supplementary Table 4). These results indicated that the lagged effect of methamphetamine use on psychotic symptoms, and psychotic symptoms on methamphetamine use, did not vary significantly among participants with either a lifetime primary or substance-induced disorder or methamphetamine dependence at baseline. Identical results were found when the three-item psychotic symptom total (unusual thought content, hallucinations, suspiciousness) was used (see supplementary Table 5).

Table 3 shows the estimates from the cross-lagged model. The model fitted the data well, CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05 and RMSEA = 0.05 (95% CI 0.04–0.06). The cross-sectional association between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms was statistically significant, b = 0.06, s.e. = 0.01, P<0.001. After adjusting for age, gender, birth country, lifetime psychotic disorder, baseline methamphetamine dependence and the cross-sectional association between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms, methamphetamine use in the previous wave significantly predicted psychotic symptoms and methamphetamine use in next wave, b = 0.09, s.e. = 0.03, P<0.001 and b = 0.39, s.e. = 0.03, P<0.001, respectively. Psychotic symptoms in the previous wave also significantly predicted methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms in the next wave, b = 0.07, s.e. = 0.03, P =0.010 and b = 0.20, s.e. = 0.03, P<0.001, respectively. Since both psychotic symptoms and methamphetamine use were standardised on a log-scale, one s.d. increase in methamphetamine use (in log-scale) was predictive of 0.09 s.d. increase in psychotic symptoms in the next wave (in log-scale), and one s.d. increase in psychotic symptoms (in log-scale) was predictive of 0.07 standard increase in methamphetamine use (in log-scale) in the next wave. That is, there was small but significant bidirectional effect between psychotic symptoms and methamphetamine use: psychotic symptoms predicted higher levels of methamphetamine use in the next month and higher methamphetamine use predicted psychotic symptoms in the next month. Comparisons of the coefficients indicated that the magnitude of the associations in each direction was similar. Identical results were found when the three-item psychotic symptom total was used (see supplementary Table 6). The exclusion of participants with a current primary psychotic disorder from the analysis did not alter results.

Table 3 Results from the cross-lagged model with fixed-effect modelling the direction of the lagged relationship between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms over 12 waves of monthly data

Discussion

Main findings

Despite evidence from three prospective studies showing methamphetamine use predicts psychotic symptoms, previous research does not appear to have examined if the reverse also applies (that psychotic symptoms also predict methamphetamine use). Monthly data on methamphetamine use and psychotic symptom severity (assessed in the same 2-week time frame) were collected from 201 regular methamphetamine users recruited from needle and syringe programmes over 1 year. Results provide preliminary evidence that the relationship between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms is bidirectional: psychotic symptoms predicted higher levels of methamphetamine use in the next month; and vice versa, higher methamphetamine use predicted psychotic symptoms in the next month. The magnitude of the relationship in each direction was small but similar in size, indicating neither direction predominated. These results add to previous research findings that methamphetamine use is predictive of psychotic symptoms,Reference Ma, Li, Wang, Li, Meng and Blow1,Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6,Reference McKetin, Dawe, Burns, Hides, Kavanagh and Teesson7 by indicating that the relationship between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms may be more reciprocal and dynamic than unidirectional.

Consistent evidence for a bidirectional association been methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms was found when both a lagged simple mixed and a more complex cross-lagged panel model were used. The cross-lagged model provided a more accurate estimate, as we were able to adjust for the prospective influence of measures of the dependent variable in the previous wave (i.e. methamphetamine or psychotic symptoms) and the cross-sectional association between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms. This method also indirectly adjusts for measured (such as lifetime alcohol and drug use) and unmeasured time-invariant potential confounders via fixed effects. The other advantage of the cross-lagged model is that it allowed examination of the bidirectional association between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms, without first ensuring the absence or stabilisation of either variable. Nevertheless, replication is needed in different cohorts of methamphetamine users.

Interpretation of our findings

This bidirectional association between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms is consistent with stress–vulnerability–coping models of psychosis, in which environmental stressors such as substance use increase risk of psychotic symptoms by reducing an individuals’ vulnerability (endophenotype) threshold for psychosis and coping resources; while continued substance use to cope with psychotic symptoms and related distress, and other stressors may serve to maintain the association.Reference Bramness, Gundersen, Guterstam, Rognli, Konstenius and Løberg21–Reference Thurn, Kuntsche, Weber and Wolstein23 The reciprocal nature of this relationship could result in more severe and chronic methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms over time, and increase risk of psychotic disorders. However, this model is yet to be tested in methamphetamine users, and although recent methamphetamine use has been associated with coping and social motives, little is known about motives for use among methamphetamine users with psychotic symptoms or disorders.Reference Bramness, Gundersen, Guterstam, Rognli, Konstenius and Løberg21,Reference Thurn, Kuntsche, Weber and Wolstein23

Previous research has suggested a neurobehavioural sensitisation process may underlie the relationship between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms; in which repeated methamphetamine use sensitises an individual to the psychotic effects of methamphetamine, such that less methamphetamine is required to induce psychotic symptoms.Reference Bramness, Gundersen, Guterstam, Rognli, Konstenius and Løberg21,Reference Weidenauer, Bauer, Sauerzopf, Bartova, Praschak-Rieder and Sitte24 Although the current study demonstrated temporal dynamic changes in the relationship between methamphetamine use and psychosis, it did not test for sensitisation. This important research question requires further investigation as part of larger-scale longitudinal studies examining the relationship between incident methamphetamine use (and other substance use) and incident psychotic (and other mental health) symptoms. Pharmacological challenge studies, finding increasing evidence for dopamine cross-sensitisation between amphetamine use and stress exposure in animals and healthy humans, also provide a promising avenue for future research testing cross-sensitisation effects on psychotic symptoms.Reference Booij, Welfeld, Leyton, Dagher, Boileau and Sibon25

Influence of diagnostic status

A secondary aim of this study was to explore whether the relationship between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms differed in participants with psychotic disorders and methamphetamine dependence. The presence of baseline methamphetamine dependence or a lifetime psychotic disorder (whether a substance-induced psychotic disorder, primary psychotic disorder, or both) had independent effects on methamphetamine use and psychotic symptom outcomes in both the simple and complex models. However, the bidirectional association between psychotic symptoms on methamphetamine use, did not vary between participants with either a lifetime primary or substance-induced disorder or with current methamphetamine dependence at baseline, in the simple model. Although we were unable to test this interaction in the complex model, because of increased model complexity and convergence problems, both lifetime psychotic disorders and methamphetamine dependence were included as covariates in that analysis. The exclusion of participants with a current primary psychotic disorder did not alter the results. Together, these results indicate that the bidirectional relationship between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms in this sample of methamphetamine users, did not vary according to whether they had methamphetamine dependence, a lifetime history of primary or substance-induced psychotic disorder or a current primary psychotic disorder.

Influence of polydrug use

Neither cannabis, alcohol nor heroin use were predictive of psychotic symptoms or methamphetamine use in this study. This was surprising given the strong associations between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms and disorders reported in previous research.Reference Volkow, Swanson, Evins, DeLisi, Meier and Gonzalez26 However, McKetin et al Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6 also found methamphetamine was more strongly associated with psychotic symptoms than cannabis or alcohol use among primary methamphetamine users, even after adjustment for other drug use. The high prevalence of polydrug use among methamphetamine users,Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6,Reference Hides, Dawe, McKetin, Kavanagh, Young and Teesson8 together with previous research showing that methamphetamine users with heavy methamphetamine, cannabis and/or alcohol use had the highest risk of psychotic symptoms, suggest that polydrug use may have a strong influence on psychotic symptoms.Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6 However, the current participants comprised primary methamphetamine users, and the individual fixed-effect term partially controlled for the frequency of cannabis, alcohol and other drug use in the cross-lagged panel models (given that there was no significant change in alcohol use and cannabis use during the study period). These two factors would have reduced the opportunity for effects of polydrug use to emerge. Future research should examine the influence of polydrug use days, as well as days of methamphetamine, cannabis, alcohol and other drug use on psychotic symptoms over time.Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its relatively large community sample and the use of frequent and detailed assessments with high follow-up rates. The use of monthly data on methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms measured on a continuous scale within the same 2-week time frame enabled us to examine the full range of variability in these variables over 1 year. Although previous research has examined this relationship over longer time frames, they used categorical definitions of methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms, assessed at only four to five time points, with minimal overlap in the time frames of measures.Reference Ma, Li, Wang, Li, Meng and Blow1,Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6 This study used the well validated BPRS positive psychotic symptom subscale, whereas previous research used only individual BPRS positive psychotic symptom items,Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6,Reference McKetin, Dawe, Burns, Hides, Kavanagh and Teesson7 or conflated them with negative psychotic and general psychopathology symptoms.Reference Ma, Li, Wang, Li, Meng and Blow1 The current study controlled for previous month methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms in the analyses, as well as a greater range of covariates (age, gender, country of birth, lifetime psychotic disorders, methamphetamine dependence, family history of psychosis, alcohol, cannabis and heroin use) than previous research. These adjustments and the reductions in methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms observed over time reduced the size of the effects. However, a significant bidirectional relationship between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms was still observed.

Research is yet to control for the potential acute effects of methamphetamine intoxication on psychotic symptoms. The BPRS and other measures of psychotic symptom severity do not differentiate primary from substance-induced symptoms. This would also be difficult to achieve in regular methamphetamine users, as there are rarely sufficient periods of abstinence to determine if psychotic symptoms are substance induced. Nevertheless, the psychotic symptoms reported in this study are unlikely to be because of the effects of acute methamphetamine intoxication, as the BPRS interview was delayed if participants had used methamphetamine in the previous 12 h. Future research using experience sampling methods, which use multiple assessments over short periods of time (for example 14 days in total), may help demarcate true psychotic symptoms from the acute effects of methamphetamine intoxication.

The limitations of this study include the fact that only information on the frequency not the quantity of substance use was collected, and the reliance on self-report measures of substance use and methamphetamine dependence. Psychotic disorders were only assessed at baseline, and it is also unclear whether the observed reductions in methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms during follow-up are fully or partially explained by reactivity to the monthly assessments. Although the focus on recruitment within needle and syringe programmes meant that most participants were injecting methamphetamine users, similar rates of injection methamphetamine use are reported in other Australian studies conducted in other contexts.Reference McKetin, Lubman, Baker, Dawe and Ali6,Reference McKetin, Najman, Baker, Lubman, Dawe and Ali27 Nevertheless, the high rates of injection methamphetamine use in this sample limit the generalisability of results, as does the fact that participants had been using methamphetamine regularly for approximately 10 years. Future research is needed to examine the impact of different routes of administration on the relationship between methamphetamine and psychosis in in both long-term regular methamphetamine users and less heavy using groups.

Implications

This study found preliminary evidence for a positive reciprocal relationship between methamphetamine and psychotic symptoms across 12 contiguous months. The dynamic nature of this relationship suggests that some individuals’ methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms may increase progressively over time, which in conjunction with (epi)genetic, psychological and environmental risk factors, could result in methamphetamine-related psychosis.Reference Bramness, Gundersen, Guterstam, Rognli, Konstenius and Løberg21,Reference Glasner-Edwards and Mooney28 However, only small effects were found and longer-term follow-up studies are required to identify which methamphetamine users are most at risk of developing substance-induced and primary psychotic disorders. Such studies would also inform the development of targeted treatments to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes among methamphetamine users with psychotic symptoms. Given the bidirectional nature of the relationship between methamphetamine use and psychotic symptoms, integrated treatments that target both simultaneously are likely to be of most benefit.

Funding

This project was funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant (APP326220). L.H. and M.T. are supported by NHMRC Senior Research and Principal Research Fellowships. G.C. is supported by an NHMRC Emerging Leadership Fellowship.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Kely Lapworth, Kristen Tulloch and Andrew Wood for their assistance with data collection.

Data availability

All authors have full ongoing access to the study data via the Griffith University Research Data Repository http://dx.doi.org/10.25904/5d5b7e54d38fe

Authors contributions

All authors have contributed to the conception and design of the study or analysis and interpretation of the data, and made substantial contributions to the writing of the article.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.263.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.