Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that there is a consistent relationship between the duration of untreated psychosis and psychosocial outcome independent of other factors. Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman1,Reference Norman, Lewis and Marshall2 However, many symptoms and a great deal of functional and social disability develop during the prodromal phase preceding the onset of first-episode psychosis. Reference Yung, Phillips, McGorry, McFarlane, Francey and Harrigan3,Reference Klosterkötter, Hellmich, Steinmeyer and Schultze-Lutter4 Neurobiological and neurocognitive changes may also occur during this pre-psychotic period. Reference Fusar-Poli, Perez, Broome, Borgwardt, Placentino and Caverzasi5 Although growing evidence suggests that a longer prodromal phase of psychosis is associated with poorer outcomes, Reference Keshavan, Haas, Miewald, Montrose, Reddy and Schooler6 such observations are based on retrospective studies and are clinically useless as preventive strategies. Psychopathological instruments are now available that allow the identification – in a longitudinal perspective – of individuals with ‘at risk’ symptoms (for a definition of ‘at risk’ symptoms see Method). As individuals who are at clinical risk for psychosis may or may not develop the disorder, Reference Yung, Phillips, McGorry, McFarlane, Francey and Harrigan3 the impact of the duration of their presenting symptoms on long-term functional outcome is mostly unknown.

Method

The setting of this longitudinal observational study was the out-patient service ‘Programma 2000’ based in Milan, Italy. This early-intervention clinical service provides 5 years of psychotherapy, psychoeducational and psychopharmacological interventions for individuals at clinical risk of psychosis. All patients at risk for psychosis assessed at the clinic between 2000 and 2006 were enrolled and followed up over a 1-year period. The inclusion criteria for being considered at clinical risk for psychosis have been developed by the Early Detection and Intervention programme of the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. Reference Bechdolf, Ruhrmann, Wagner, Kühn, Janssen and Bottlender7 Clinical assessment was performed using the Early Recognition Inventory (ERIraos), Reference Maurer, Horrmann, Schmidt, Trendler and Hafner8,Reference Häfner, Maurer, Ruhrmann, Bechdolf, Klosterkötter and Wagner9 which defines the prodromal state as one of the following: (a) presenting with certain self-experienced cognitive thought and perception deficits (‘basic symptoms’ according to Klosterkotter et al Reference Klosterkötter, Hellmich, Steinmeyer and Schultze-Lutter4 ); and/or (b) demonstrating a clinical decline in functioning in combination with other well-established risk factors. Reference Yung, Phillips, McGorry, McFarlane, Francey and Harrigan3 Exclusion criteria were: being aged <18 and >36, presenting with any medical conditions or any previous diagnosis of a schizophrenic, schizophreniform, schizoaffective, delusional, bipolar or brief psychotic disorder according to DSM–IV. Reference Bechdolf, Ruhrmann, Wagner, Kühn, Janssen and Bottlender7 Socio-demographic characteristics were recorded via an unstandardised questionnaire and clinical assessment was conducted by two psychiatrists. Psychopathological characteristics of the sample were collected by using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) Reference Overall and Gorham10 , ERIraos, Reference Maurer, Horrmann, Schmidt, Trendler and Hafner8 Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) 11 and Health of the Nation Scale (HoNOS) Reference Wing, Beevor, Curtis, Park, Hadden and Burns12 instruments at baseline (first contact with the prodromal service), 6 and 12 months. Duration of untreated ‘at risk’ symptoms was operationally defined as the first onset of specific basic symptoms as assessed using ERIraos: thought interference; thought perseveration; thought pressure; thought blockage; disturbances of receptive language; decreased ability to discriminate between ideas and perception and between fantasy and true memories; unstable ideas of reference (subject-centrism); derealisation; visual perception disturbance; and acoustic perception disturbance. Reference Bechdolf, Ruhrmann, Wagner, Kühn, Janssen and Bottlender7 All participants gave informed consent to be part of the study.

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations for continuous variables and relative frequencies for categorical variables) were computed. Mean and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of BPRS, GAF, ERIraos and HoNOS at baseline, 6 months and 12 months were also calculated. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess changes in BPRS, GAF, ERIraos and HoNOS scores over the three time points. Pearson's correlation coefficients (R) were computed to estimate the correlation between GAF change (GAF after 12 months – GAF at baseline) and baseline characteristics. The association between the primary outcome (GAF change) and predictors was assessed by a general linear regression analysis, after checking for collinearity. The choice between collinear variables was based on clinical considerations. Variation due to the association model was estimated by the R2 statistic. SPSS V.15 for Windows was used for all statistical analyses. Two-tailed P-values <0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 49 individuals (65% males) participated in the study (9 of the original sample of 58 participants did not complete the follow-up assessments). There were no significant socio-demographic differences between male and female participants (t-tests, P>0.05). Socio-demographic data and scores on the BPRS, GAF, HoNOS and ERIraos at baseline, 6-month and 12-month follow-up are reported in online Table DS1. Repeated-measures ANOVA of clinical ratings across time points (baseline, 6 months and 12 months) showed a significant improvement in GAF (F=48.86, d.f.=2, P<0.001), HoNOS (F=20.85, d.f.=2, P<0.001), ERIraos (F=34.82, d.f.=2, P<0.001) and BPRS (F=31.11, d.f.=2, P<0.001) scores over time.

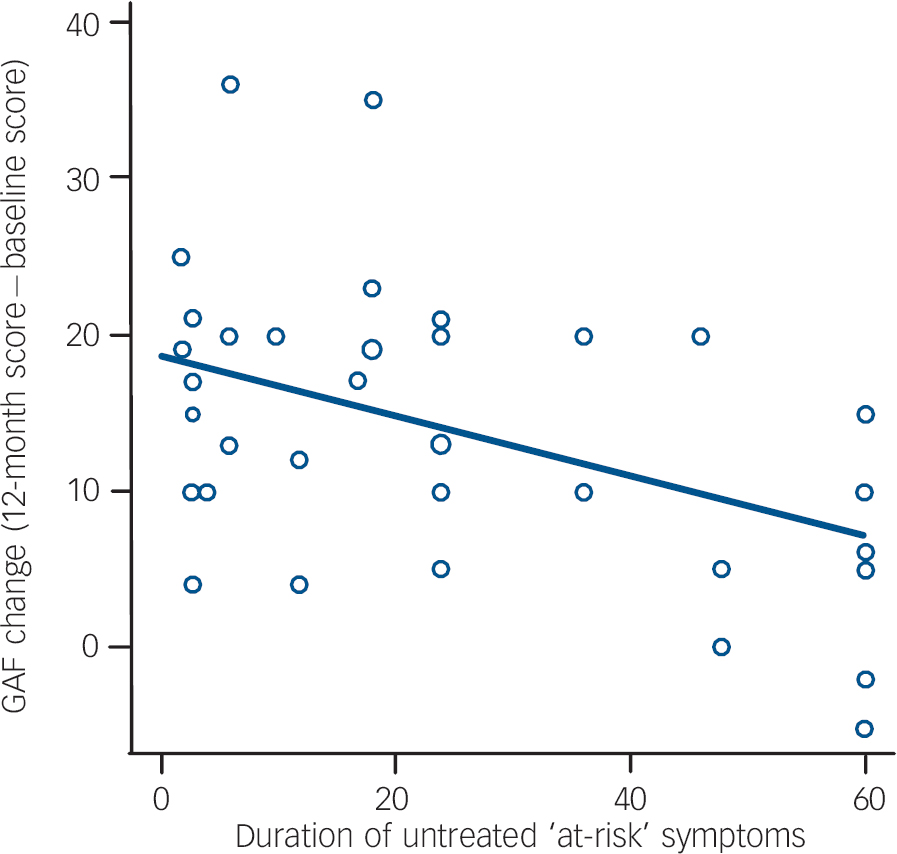

A significant negative correlation between GAF score change over 12 months and duration of the untreated ‘at risk’ symptoms at baseline was observed (r=–0.494, P=0.001; Fig. 1), but the correlations between GAF change and baseline BPRS, ERIraos, HoNOS and age were non-significant (r=–0.008, P=0.960; r=–0.065, P=0.683; r=–0.012, P=0.938; r=–0.030, P=0.849 respectively).

Fig. 1 Correlation between duration of untreated ‘at risk’ symptoms and change in Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score in individuals at clinical risk of psychosis.

We then built the regression model entering different factors (online Table DS2) and tested it, confirming that the duration of untreated ‘at risk’ symptoms was negatively associated with change in GAF scores (standardised β coefficient=–0.375, P=0.008). There was a moderate, albeit non-significant (P>0.01), association between GAF outcomes at 12 months and being a graduate (standardised β=0.367, P=0.012) and being employed (standardised β=0.300, P=0.030). The model remained significant after adjusting for age, gender and symptoms (BPRS at 12 months – BPRS at baseline) and was able to explain 51% of the variance.

Discussion

The low predictive value and the high rate of false positives associated with the available assessment instruments for people at risk of psychosis have raised methodological criticisms and several ethical concerns regarding interventions in pre-psychotic phases. Reference Cornblatt, Auther, Niendam, Smith, Zinberg and Bearden13 However, in line with evidence showing that preventive intervention in psychosis is feasible and effective, in our sample the global functioning of individuals at clinical risk for psychosis improved over the 12-month follow-up, presumably because of treatment. Despite these encouraging findings, young people seeking help from prodromal services may have been experiencing attenuated psychotic symptoms and psychosocial impairments for a long period before referral. In fact, we found that, on average, the first contact with prodromal services is preceded by a period of more than 2 years in which individuals are experiencing subtle and attenuated ‘at risk’ symptoms. In addition, we found that the duration of these untreated ‘at risk’ symptoms has a detrimental effect on long-term global functioning (Fig. 1). Previous cross-sectional studies have confirmed that individuals at risk for schizophrenia have significant functional deficits Reference Ballon, Kaur, Marks and Cadenhead14 that precede overt symptom formation. Reference Melle, Haahr, Friis, Hustoft, Johannessen and Larsen15

Duration of untreated ‘at risk’ symptoms may be a potentially modifiable prognostic factor through a nationwide development of prodromal services and a rapid referral of ‘at risk’ individuals. Although our study is limited by a small sample size and psychopathological heterogeneity across individuals at risk for psychosis, our findings support a very early detection of ‘at risk’ symptoms. Early diagnosis and early intervention services based in primary care and in the wider community (e.g. school counsellors, job centres and community youth centres) could improve long-term functioning of at-risk individuals independent of clinical outcome. A selective focus on the general functioning of the patient instead of their symptomatic profile seems to be one of the most promising end-point measures in future preventive interventions. Understanding the mechanism by which the duration of untreated ‘at risk’ symptoms interacts with environmental and genetic factors leading to transition to psychosis will also shed light on the pathophysiology of the prodromal phases of psychoses and may help improve treatment strategies.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.