Thoughts about death are not uncommon in later life, particularly in extreme old age. Reference Bartels, Coakley, Oxman, Constantino, Oslin and Chen1 Their presence is strongly associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, Reference Bartels, Coakley, Oxman, Constantino, Oslin and Chen1 and in some cases may evolve to self-harm ideation and suicide. Reference Lawrence, Almeida, Hulse, Jablensky and Holman2,Reference Pfaff and Almeida3 Various factors are thought to contribute to the development of self-harm ideation in later life, the most common being the presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms. Reference Pfaff and Almeida4 A review of psychological autopsy studies completed in the past decade showed that 46–86% of older adults who died by suicide displayed symptoms consistent with a mood disorder in the weeks preceding their death, Reference Conwell, Van Orden and Caine5 which suggests that the successful prevention and management of depression might reduce the rate of suicide in this age group, particularly among men. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas6 Not surprisingly, most suicide prevention strategies introduced to date have focused on increasing the detection of depression and optimising its management in primary care. Reference Bruce and Pearson7,Reference Rihmer, Rutz and Pihlgren8 Collaborative care strategies, for example, have been successful at reducing the severity of depressive symptoms and the prevalence of suicide ideation in older adults with depression, Reference Bruce, Ten Have, Reynolds, Katz, Schulberg and Mulsant9 but benefits have been modest and the long-term sustainability of such programmes remains uncertain. Reference Gilbody, Bower and Whitty10

One possible explanation of the limited success of depression-focused interventions in reducing the prevalence of suicide ideation in later life is that other, untargeted factors may drive this association. For example, the rate of suicide in later life is higher in men than in women, as well as in people with pain and multiple medical morbidities, Reference Van Orden and Conwell11 marked feelings of hopelessness, Reference Rifai, George, Stack, Mann and Reynolds12 financial concerns and loneliness. Reference Rubenowitz, Waern, Wilhelmson and Allebeck13 There is also evidence that older people with overlapping anxiety and depressive symptoms may be particularly vulnerable to the onset of suicide ideation, Reference Mykletun, Bjerkeset, Dewey, Prince, Overland and Stewart14 and it is possible that the increasing sense of edginess and psychological discomfort associated with anxiety are important contributing factors that demand attention and treatment. However, given the multitude of factors that have been associated with suicide ideation and behaviour in later life, the design of data-driven preventive strategies would benefit from data derived from large community studies that measure simultaneously the relevant demographic, lifestyle, psychosocial and clinical variables in order to minimise confounding and enhance the generalisability of the data. We report data derived from a community study of over 20 000 older Australians, intended to determine the independent contribution of demographic, lifestyle, socioeconomic, psychiatric and medical factors to the presence of suicide ideation.

Method

Study design and participants

Our analyses are based on data originating from the Depression and Early Prevention of Suicide in General Practice study. Details regarding the recruitment have been reported elsewhere. Reference Almeida, Pirkis, Kerse, Sim, Flicker and Snowdon15 Briefly, between May and December 2005 all patients aged 60 years or over of participating primary care practices in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia were sent a questionnaire, a personalised cover letter from their general practitioner, project information, a consent form and a reply-paid envelope addressed to the project office. We asked potential participants to return the questionnaires (blank in the case of non-consent) so that we could estimate the true denominator of the target population. We received 22 258 questionnaires with written informed consent. Another 9087 questionnaires were returned not completed, 2934 were returned to the sender because the person named on the envelope was not known at the address and 820 failed to be posted because of mishandling of the envelopes by the company organising the mail-out (the total number of questionnaires tracked was 35 099). A small number of people who consented were found to be ineligible because they were under 60 years old (n = 120) or did not reside in the community (nursing home; n = 54). A further 229 questionnaires had incomplete data on age and 30 were duplicates, leaving a sample of 21 825 persons, of whom 21 290 reported information on suicide ideation. The ethics committees of the University of Western Australia, the University of Melbourne and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners approved the study protocol and all participants provided informed consent.

Primary outcome

The outcome of interest was suicidal ideation according to the Depressive Symptom Inventory –Suicidality Subscale. Reference Metalsky and Joiner16,Reference Joiner and Rudd17 This is a four-item self-report questionnaire that assesses 2-weekly suicidal ideation (thoughts about killing oneself), degree to which a plan has been formulated, ability to control suicidal thoughts (from complete to little or no control) and suicidal impulses (intensity of impulse to act on suicidal thoughts). Scores on each item range from 0 to 3, with higher scores reflecting greater severity of suicidal ideation. Older adults who scored 1 or more on any of these four questions were considered to represent prevalent cases of suicidal ideation.

Other study measures

Participants provided information about their gender, place of birth (Australia v. overseas), marital status, highest educational achievement and date of birth, which we used to calculate their age (in years). We also asked them whether, as a rule, they took at least half an hour of moderate or vigorous exercise on five or more days of the week (yes/no), Reference Elley, Kerse and Arroll18 whether they smoked (never, past, current) and how many standard drinks they normally had on each typical day of the week. People who reported consuming seven or more drinks on any one day or who had three or more drinks nearly every day were considered risk drinkers. 19 We used self-reported height and weight to calculate the body mass index (BMI), and classified as overweight or obese participants with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or above. We collected information about living arrangements (alone v. with others) and used the Duke Social Support Index to measure perceived social support. Reference Koenig, Westlund, George, Hughes, Blazer and Hybels20 Scores on this index of 26.5 or below represented the lowest quartile of scores in our sample and were used as an indicator of poor social support. Respondents scoring in the lowest quintile of the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage were considered socially disadvantaged. Reference Pink21 In addition, participants indicated whether they attended religious services regularly (yes/no) and whether they were experiencing financial strain (distinctly or very much v. slightly or not at all). Study participants recorded whether they had lost a parent or experienced physical or sexual abuse before they were 15 years old (yes/no). They also indicated whether any immediate family member had died by suicide (yes/no).

Older adults in the study recorded whether a doctor had ever told them they had an anxiety disorder or depression (yes/no) and whether they had ever attempted to kill themselves in their lifetime (never/once or more than once) or during the past year (never/once or more than once). Participants rated their overall health as fair/poor or good to excellent, and indicated whether pain had interfered with their usual activities during the preceding 4 weeks (no/little or moderately to extremely). We assessed prevalent symptoms of anxiety and depression with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Reference Zigmond and Snaith22 Possible scores range from 0 to 21 for each subscale (HADS-A for anxiety and HADS-D for depression), with scores of 11 or above indicating the presence of clinically significant anxiety or depression. Reference Zigmond and Snaith22 We used the scores on these subscales to assign participants to one of four groups: no anxiety or depression (HADS-A and HADS-D <11); anxiety but no depression (HADS-A ⩾11 and HADS-D <11); depression but no anxiety (HADS-D ⩾11 and HADS-A <11); and anxiety and depression (HADS-A ⩾11 and HADS-D ⩾11). Participants recorded whether they had ever been told by a doctor that they had any of the following conditions (yes/no): arthritis, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, heart attack or angina, heart failure, poor circulation in the legs, asthma, emphysema, osteoporosis, cancer (except skin cancer), dementia, thyroid disease and head injury. We grouped them according to the number of reported medical morbidities: 0; 1 or 2; 3 or 4; 5 or more. Finally, we asked participants to record the names of any medicines they had used during the preceding 2 weeks, and from this list we retrieved information about the use of benzodiazepines or antidepressants (any class).

Statistical analysis

Data were managed and analysed with Stata version 12.0 for Mac. We used descriptive statistics to summarise the data and cross-tabulation to determine their distribution according to the presence of suicide ideation. We used Pearson's chi-squared statistic to estimate whether differences in the distribution of measured factors between the groups could have arisen by chance. We then investigated the association between measured factors (independent variables) and the suicide ideation grouping (dependent variable) using logistic regression. The reported odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval were derived from a multivariate model that included all measured factors. We subsequently created a parsimonious model of suicidal ideation where only variables associated at a significance level of P<0.05 were retained (stepwise backwards regression), and used the effect estimates to calculate the fraction of suicidal ideation that could be attributed to the exposures in the model (command: punaf). In this study the population attributable fraction (PAF) offers an indication of the proportion of people with suicidal ideation who would no longer report suicidal thoughts if the relevant exposure (e.g. pain) could be removed (all other variables in the model held constant). This approach assumes that the exposure is causally related to the outcome. Alpha was set at 5% and all probability tests used were two-tailed.

Results

Of 21 290 participants, 1023 (4.8%) acknowledged the presence of suicide ideation during the preceding 2 weeks. The age range of the sample was 60–101 years, and the mean age of participants with suicide ideation was 70.5 (s.d. = 7.9) years compared with 71.9 (s.d. = 7.6) years for those without such ideation (t = 5.38, P<0.001). Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic, lifestyle and socioeconomic characteristics of those with and without suicide ideation, and Table 2 shows participants’ clinical characteristics. There was a significant excess of men, migrants, unmarried and highly educated people among the ideation group, who were also more physically inactive, overweight or obese, past or current smokers and risky alcohol users. Compared with those who denied ideation, a greater proportion of people experiencing thoughts of suicide lived alone, had poor social support, did not practise a religion, were experiencing financial stress, had lost a parent or had been recipients of physical or sexual abuse during childhood, and reported a history of suicide in the family. More people in the suicide ideation group than in the non-ideation group had a history of anxiety or depressive disorder, a past suicide attempt, pain or poor self-perceived health and multiple medical morbidities. The proportion of respondents with clinically significant anxiety, depression or comorbid anxiety and depression was larger in the suicide ideation group. Finally, more people reporting suicidal ideation were using benzodiazepines and antidepressants.

TABLE 1 Demographic, lifestyle and psychosocial characteristics of the participants categorised by suicidal ideation

| No suicidal ideation (n = 20 267), n (%) |

Suicidal ideation (n = 1023), n (%) |

Univariate odds ratio of suicidal ideation (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic information | |||

| Age, years | |||

| 60–64 | 4117 (20.3) | 311 (30.4) | 1 (reference) |

| 65–69 | 4831 (23.8) | 230 (22.5) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) |

| 70–74 | 4144 (20.4) | 190 (18.6) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) |

| 75–79 | 3494 (17.2) | 134 (13.1) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) |

| 80–84 | 2355 (11.6) | 87 (8.5) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) |

| 85+ | 1326 (6.5) | 71 (6.9) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| Male gender | 8337 (41.2) | 463 (45.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) |

| Migrant | 5157 (25.5) | 296 (29.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| Not married | 6552 (32.4) | 465 (45.6) | 1.8 (1.5–2.0) |

| Higher education | 2930 (14.7) | 184 (18.4) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| Had children | 18 486 (97.0) | 909 (97.0) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) |

| Lifestyle variables | |||

| Physically inactive | 7321 (36.5) | 492 (48.4) | 1.6 (1.4–1.9) |

| Overweight or obese | 11 544 (64.1) | 623 (69.4) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 10 565 (52.4) | 407 (40.2) | 1 (reference) |

| Past | 8399 (41.7) | 458 (45.2) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) |

| Current | 1197 (5.9) | 148 (14.6) | 3.2 (2.6–3.9) |

| Alcohol use | |||

| None | 4956 (24.7) | 270 (26.7) | 1 (reference) |

| Non-risk use | 12 611 (62.9) | 578 (57.2) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) |

| Risky use | 2490 (12.4) | 162 (16.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| Socioeconomic history | |||

| Living alone | 4797 (23.7) | 321 (31.5) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) |

| Poor social support | 4419 (22.5) | 665 (67.4) | 7.1 (6.2–8.2) |

| Social disadvantage | 3905 (19.9) | 189 (19.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) |

| No religious practice | 10 865 (53.8) | 638 (62.5) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) |

| Financial strain | 1873 (9.6) | 285 (29.0) | 3.9 (3.3–4.5) |

| Loss of a parent during childhood | 2544 (12.6) | 171 (16.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) |

| Childhood physical abuse | 1218 (6.0) | 194 (19.1) | 3.7 (3.1–4.3) |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 1221 (6.0) | 165 (16.2) | 3.0 (2.6–3.6) |

| Suicide in family | 1137 (5.6) | 117 (11.6) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) |

TABLE 2 Clinical characteristics of the participants categorised by suicidal ideation

| No suicidal ideation (n = 20 267), n (%) |

Suicidal ideation (n = 1023), n (%) |

Univariate odds ratio of suicidal ideation (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Past anxiety disorder | 1696 (8.4) | 269 (26.3) | 3.9 (3.4–4.2) |

| Past depressive disorder | 3149 (15.5) | 566 (55.3) | 6.7 (5.9–7.7) |

| HADS status | |||

| Neutral | 17 943 (93.6) | 509 (52.1) | 1 (reference) |

| Anxiety | 698 (3.6) | 173 (17.7) | 8.7 (7.3–10.5) |

| Depression | 291 (1.5) | 92 (9.4) | 11.1 (8.7–14.3) |

| Anxiety and depression | 244 (1.3) | 203 (20.8) | 29.3 (23.9–36.0) |

| Past suicide attempt | 368 (1.8) | 131 (12.8) | 7.9 (6.4–9.8) |

| Suicide attempt past year | 15 (0.1) | 25 (2.4) | 33.8 (17.8–64.3) |

| Pain | 5883 (29.2) | 595 (58.6) | 3.4 (3.0–3.9) |

| Poor perceived health | 4222 (21.0) | 523 (51.3) | 4.0 (3.5–4.5) |

| Medical morbidities | |||

| 0 | 2004 (9.9) | 63 (6.2) | 1 (reference) |

| 1–2 | 9765 (48.2) | 370 (36.2) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) |

| 3–4 | 6398 (31.6) | 383 (37.4) | 1.9 (1.5–2.5) |

| 5+ | 2100 (10.4) | 207 (20.2) | 3.1 (2.3–4.2) |

| Use of benzodiazepines | 1404 (6.9) | 173 (16.9) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) |

| Use of antidepressants | 2202 (10.9) | 332 (32.4) | 3.9 (3.4–4.5) |

HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

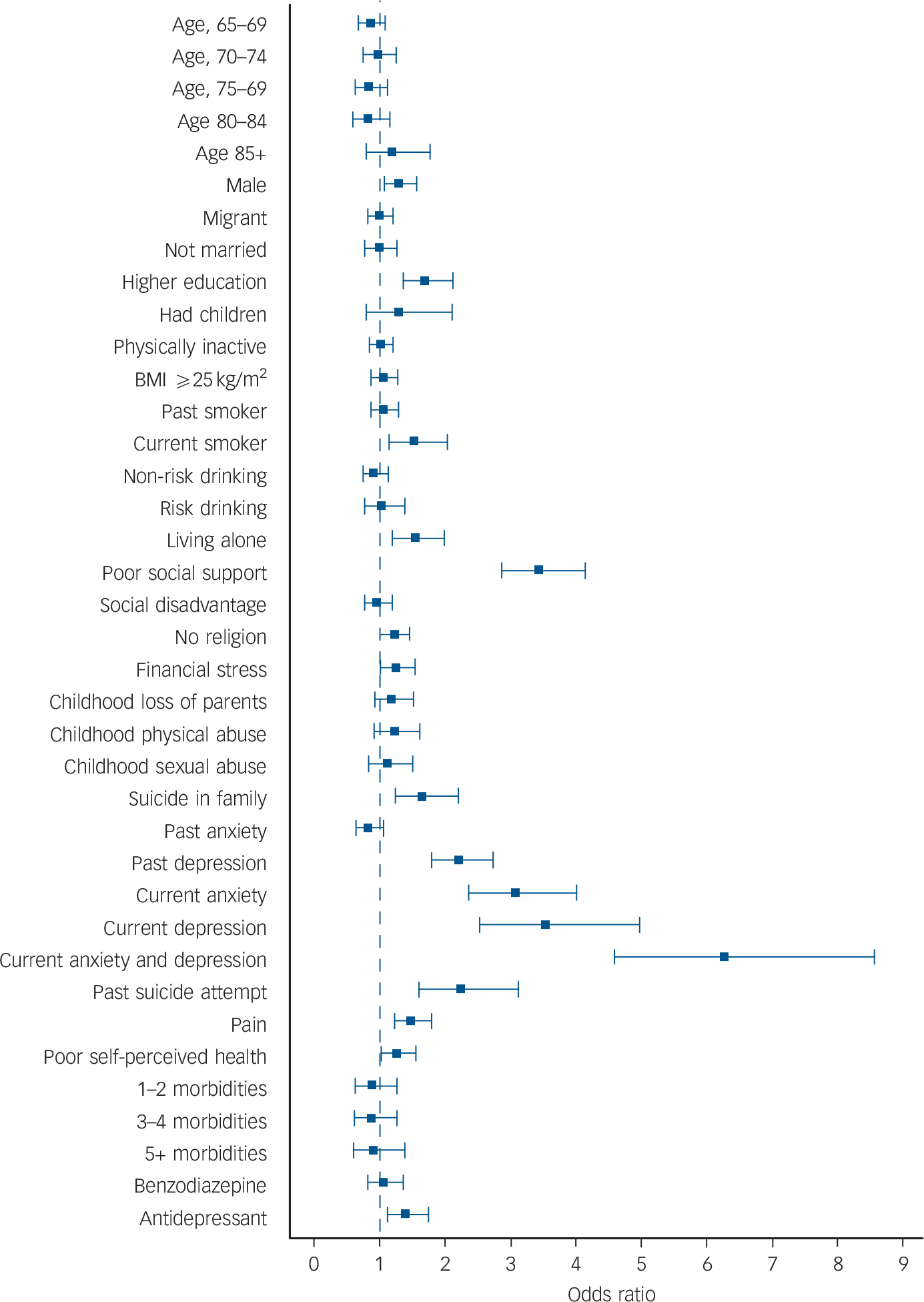

We used multivariate logistic regression to determine the odds of suicide ideation for all measured factors listed in Tables 1 and 2 (all factors forced simultaneously into the model). The results are illustrated in Fig. 1. Male gender, possessing a higher degree, being a current smoker, living alone, being in the lowest quintile of social support, practising no religion, experiencing financial stress, reporting a history of suicide in the family or of past depression, presenting clinically significant symptoms of anxiety, depression or of comorbid anxiety and depression, experiencing moderate to severe pain or poor self-perceived health, and using antidepressants were all independently associated with increased risk of prevalent suicide ideation (pseudo R 2 = 25.5% for the multivariate model).

FIG. 1 Odds ratio of suicide ideation according to various demographic, lifestyle, psychosocial and clinical factors.

All variables were forced together into a multivariate logistic regression model. The squares indicate the odds ratio and the whiskers the 95% confidence limits of the odds ratio. BMI, body mass index.

The parsimonious logistic regression model of suicide ideation, which included only exposures associated at P<0.05, appears in Table 3 (pseudo R 2 = 25.4%). Variables significantly associated with suicide ideation were male gender, higher education, current smoking, living alone, poor social support, no religious practice, financial strain, childhood physical abuse, history of suicide in the family, past depression, current anxiety, depression or comorbid anxiety and depression, past suicide attempt, pain, poor self-perceived health and current use of antidepressants. We also calculated the PAF for each of the independent variables of the parsimonious model (Table 3). Poor social support was associated with a PAF of 38.0%, followed by history of depression (23.6%), concurrent anxiety and depression (19.7%), prevalent anxiety (15.1%), pain (13.7%) and no religious practice (11.4%). All other variables in the model were associated with significant PAFs that were lower than 10%.

TABLE 3 Odds ratio and population attributable fraction of suicide ideation according to exposures derived from a multivariate logistic regression model

| OR (95% CI) | PAF% (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 7.2 (1.9–12.3) |

| Higher education | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 6.6 (3.8–9.2) |

| Current smoker (v. never smoked) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 4.7 (0.3–8.9) |

| Living alone | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | 8.1 (4.4–11.7) |

| Poor social support | 3.1 (2.6–3.7) | 38.0 (32.2–43.4) |

| No religious practice | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 11.4 (4.3–18.0) |

| Financial strain | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 4.6 (1.2–8.0) |

| Childhood physical abuse | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 3.0 (0.3–5.6) |

| Suicide in family | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 2.9 (0.9–4.8) |

| Past depressive disorder | 2.3 (1.9–2.8) | 23.6 (17.9–28.9) |

| HADS status | ||

| Anxiety | 3.3 (2.6–4.1) | 15.1 (11.3–18.7) |

| Depression | 3.6 (2.7–5.0) | 8.8 (6.0–11.6) |

| Anxiety and depression | 7.1 (5.4–9.3) | 19.7 (16.5–22.8) |

| Past suicide attempt | 2.3 (1.7–3.1) | 4.5 (2.7–6.3) |

| Pain | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) | 13.7 (7.3–19.6) |

| Poor perceived health | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 7.6 (1.7–13.2) |

| Antidepressant use | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 4.8 (0.7–8.7) |

HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PAF, population attributable fraction.

Discussion

The results of this large community-based study show that nearly 5% of older Australians acknowledged suicidal thoughts in the preceding 2 weeks, a rate that is within the range of suicide ideation in the preceding month (2.3–15.9%) noted in world literature. Reference De Leo, Krysinska, Bertolote, Fleischmann, Wasserman, Wasserman and Wasserman23 Our study was sufficiently large to explore the independent association with suicide ideation of numerous demographic, lifestyle, socioeconomic and clinical variables, including male gender, higher education, smoking, living alone and having limited social support, not practising a religion, experiencing financial stress, family history of suicide, history of depression or of suicide attempt, current anxiety, depression or comorbid anxiety and depression, pain, poor self-perceived health and use of an antidepressant. The risk of suicide ideation was particularly high among people with concurrent anxiety and depression, followed by those with prevalent depression but no anxiety and by those with prevalent anxiety but no depression. Poor social support was associated with the largest PAF, followed by a self-reported history of medically diagnosed depression, prevalent concurrent anxiety and depression, prevalent anxiety with no depression, pain and no religious practice.

Limitations of the study

Before discussing the implications of our findings we should consider how the characteristics of the study could potentially affect the interpretation of the results. We recruited a large sample of community-dwelling older adults that was broadly representative of the Australian community, Reference Pirkis, Pfaff, Williamson, Tyson, Stocks and Goldney24 although the response rate to invitations was not optimal and may have introduced bias as a result of healthy people being more willing to participate. The consequence of such a bias would have been a reduction in the number of people who were unwell, possibly including cases of suicide ideation, anxiety and depression. This might have reduced the strength of the association between suicide ideation and health morbidities, as well as our ability to adjust the statistical models for poor health. Hence, the effect estimates of the association between the exposures and suicide ideation may have decreased because of selection bias or increased because of confounding. Our study was sufficiently large to declare as significant odds ratios as small as 1.3, and as odds ratios smaller than this are unlikely to be of clinical significance, it seems improbable that our results would have been severely affected by loss of power. In addition, the effect of the number of medical morbidities in the analysis was not significant, which suggests that confounding due to poor health should not have influenced the results substantially.

We used a well-validated approach to assess suicide ideation, Reference Metalsky and Joiner16,Reference Joiner and Rudd17 but acknowledge that thinking about killing oneself is not the same as attempting or completing suicide. Thus, it may be argued that our findings are relevant for suicidal thoughts rather than for behaviour. Indeed, suicide attempt and completion are rare occurrences compared with suicidal ideation in later life, Reference Lawrence, Almeida, Hulse, Jablensky and Holman2,Reference Pfaff and Almeida4 and most people who consider ending their lives never attempt suicide. However, suicidal thoughts are nearly always present before suicide completion, Reference Waern, Beskow, Runeson and Skoog25,Reference Conwell, Duberstein, Cox, Herrmann, Forbes and Caine26 so that reducing the prevalence of suicide ideation is a necessary step of suicide prevention programmes.

The interpretation of our results should also take into account the underlying assumption that the association between the exposures (risk factors) and suicide ideation is causal. Causality cannot be inferred from cross-sectional studies such as ours, nor can we dismiss the possibility of reverse associations entirely. For example, it is conceivable that people who think about suicide feel distressed by such a thought, and this in turn could lead to the onset of clinically significant symptoms of anxiety. In this scenario, anxiety would be a consequence rather than a cause of suicidal thoughts. However, evidence from other sources suggests that anxiety precedes the onset of suicide ideation, Reference Sareen, Cox, Afifi, de Graaf, Asmundson and ten Have27 thereby undermining the hypothesis of reverse causality. The remission of most suicidal thoughts associated with the successful treatment of depression would similarly argue against the possibility that such ideas would cause depressive symptoms. Reference Alexopoulos, Reynolds, Bruce, Katz, Raue and Mulsant28 Finally, other factors associated with prevalent suicide ideation in our study would seem less susceptible to reverse causality (e.g. male gender, higher education, smoking, poor social support, no religious practice, childhood physical abuse, history of suicide in the family, past suicide attempt, past depressive episode), but uncertainty remains for some of the exposures that we measured, such as use of antidepressants and subjective experience of pain.

We had access to information about relevant exposures, but acknowledge that using the HADS to establish the presence of anxiety and depression is not the same as using structured clinical interviews or diagnostic criteria. Reference Zigmond and Snaith22,Reference Bjelland, Dahl, Haug and Neckelmann29 Hence, we cannot be certain that our findings would be directly transferable to patients with anxiety and mood disorders defined according to DSM criteria. Finally, we used a reliable measure of perceived social support, Reference Koenig, Westlund, George, Hughes, Blazer and Hybels20 but did not have access to objective information about social network structure and size, actual support received or disability. Reference Dennis, Baillon, Brugha, Lindesay, Stewart and Meltzer30 Therefore, it seems possible that some of the associations that we observed could be explained, at least in part, by unmeasured factors.

Interpretation

The results of this study indicate that the risk of suicidal ideation is 7 times as high in older adults with concurrent anxiety and depression as in those without anxiety or depression, which suggests that everyone in this age group with such a clinical presentation should be screened for the presence of suicidal thoughts. Reference Bartels, Coakley, Oxman, Constantino, Oslin and Chen1,Reference Pfeiffer, Ganoczy, Ilgen, Zivin and Valenstein31 Similarly, in this sample the odds of suicide ideation were respectively 3.6 and 3.3 times higher among those with prevalent depression but no anxiety and those with prevalent anxiety but no depression. Reference Lawrence, Almeida, Hulse, Jablensky and Holman2,Reference Sareen, Cox, Afifi, de Graaf, Asmundson and ten Have27,Reference Bolton and Robinson32 Although perceived poor social support increased the odds of suicide ideation by 3.1 times, it was associated with the largest PAF (38.0%) in our model, followed by self-reported history of depression (PAF 23.6%), prevalent concurrent anxiety and depression (PAF 19.7%), prevalent anxiety but no depression (PAF 15.1%), pain (PAF 13.7%) and no religious practice (PAF 11.4%). Notwithstanding the statistical robustness of the PAFs associated with measured exposures in our study, some caution is required when interpreting these results. A key assumption underlying valid estimates is that the relationship between the exposures and the outcome is causal and independent. Reference Rockhill, Newman and Weinberg33 We have modelled our data to ensure the reported PAFs were independent, but are unable to establish causality from our cross-sectional study; such a shortcoming can only be overcome by properly conducted randomised trials. Other major contributing factors included male gender, higher education, smoking, living alone, no religious practice, financial strain, childhood physical abuse, family history of suicide, past suicide attempt, poor perceived health and antidepressant use, the importance of which has been previously highlighted by others. Reference Pfaff and Almeida4,Reference Conwell, Van Orden and Caine5,Reference Turvey, Conwell, Jones, Phillips, Simonsick and Pearson34,Reference Lapierre, Erlangsen, Waern, De Leo, Oyama and Scocco35 However, we are not aware of any study that had sufficient power to examine the independent contributions of the wide range of demographic, lifestyle, socioeconomic and clinical factors that we examined in this study.

Our findings suggest that suicide prevention strategies limited to older adults with mood disorders, although efficacious, Reference Alexopoulos, Reynolds, Bruce, Katz, Raue and Mulsant28,Reference Unutzer, Tang, Oishi, Katon, Williams and Hunkeler36 may have only limited impact on the overall prevalence of suicidal thoughts in the population. Indicated or selective preventive programmes, targeting people with symptoms or those at risk, might have greater impact on the prevalence of suicidal ideation if relevant social, demographic, lifestyle and medical factors were also addressed. In fact, our data indicate that social factors (poor perceived social support and living alone) may have a particularly prominent role in this age group and, although their management is challenging, preliminary evidence suggests that interventions such as telephone support and befriending might be feasible and helpful. Reference De Leo, Dello Buono and Dwyer37 In fact, one might speculate that women respond better than men to suicide prevention programmes because their participation reduces the sense of social isolation associated with living alone, a factor that may be less relevant to men. Reference Lapierre, Erlangsen, Waern, De Leo, Oyama and Scocco35 Nonetheless, increasing opportunities for social interaction may fail to reduce the experience of loneliness and social isolation of people with mental health disorders if maladaptive social cognitions (e.g. heightened sensitivity to perceived social threats) are not managed appropriately. Reference Meltzer, Bebbington, Dennis, Jenkins, McManus and Brugha38 Indeed, a detailed meta-analysis of trials designed to reduce loneliness concluded that interventions that addressed maladaptive social cognitions were the most helpful. Reference Masi, Chen, Hawkley and Cacioppo39 If the findings reported for loneliness are equally applicable to perceived social support in later life, future preventive programmes will need to consider whether to increase opportunities for social interaction, target maladaptive social cognitions, or both, in order to decrease the prevalence of suicidal ideation. Our results also support the view that, consistent with models of late-life depression, Reference Almeida, Alfonso, Pirkis, Kerse, Sim and Flicker40 a life-cycle approach to suicide prevention must be considered, as early and midlife factors may contribute to modulate the presence of late psychosocial risk factors and clinical presentations. Well-designed randomised trials targeting vulnerable populations are now needed to guide policy and practice.

Funding

The study was supported by the project grant number 353569 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and by an infrastructure grant from beyondblue Australia.

Acknowledgements

The investigators thank participants and research staff for their generous contribution.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.