In December 2018, the BJPsych published an editorial on gender inequalities in science, outlining the continued challenges that women face, including significant pay differentials and poor visibility in senior positions. Here, we continue the discussion and outline how gender inequality in academic publishing and academic psychiatryFootnote a will be tackled head on in the BJPsych.

The challenge

Women have been equally represented or over-represented in UK medical student placements for some time. However, in academic medicine, representation is far less equal. In the UK, women currently constitute 45% of all doctors, 26% of clinical academics and 15% of professors. Within medical specialties, the lowest representation across all academic career stages is seen in surgery, at 16%, and highest in obstetrics and gynaecology, at 33%, with psychiatry coming in at 28%. The majority of these posts are not in senior (professorial) positions. There are currently 25 female professors of psychiatry in the UK out of a total 110 (23%). Although this appears to be an improvement over recent years, it might reflect a fall in numbers of professors of psychiatry overall, losing more male posts than a net increase in women. Improvement in gender representation appears to be stronger in general medicine: in 2007 there were 45 female professors out of 506 (9%), increasing to 109 females out of 620 (17%) in 2019.1

Academic success and academic publishing are inherently linked. Successful publishing can significantly help successful grant capture, and vice versa. Evidence shows that women in academia have fewer high-impact publications and are less likely to be in senior author positions. Papers authored by women are more likely to be rejected and spend longer in review than those authored by men. Self-promotion and aggrandisement of work is more often seen in male authors; in an analysis of over six million clinical research and life science articles, men generally used more positive and extreme words (e.g. ‘transformative’, ‘excellent’, ‘novel’ and ‘unique’) to describe their research work, and this presentation is associated with greater numbers of citations.Reference Lerchenmueller, Sorenson and Jena2 Evidence also suggests that women have lower grant income, yet when they apply for grants, in the UK recently they are equally likely to be successful.3 Thus, fewer women are applying for grants than men, and for smaller amounts when they do apply. Authorship, grant income and senior position on publications in highly regarded journals are crucially important to academic departments and make a significant difference in terms of job success and promotion to senior academic positions. A lower rate of publishing and smaller grant capture leaves women on a slower trajectory of prominence, influence and positioning as leaders in an academic field.

Men are more likely to achieve senior academic positions at a younger age, and therefore have longer to build departments, influence institutions, mentor juniors and leave a legacy. Once in mid-career positions (e.g. senior lecturer) women are more likely be given additional pastoral, administrative and teaching duties in perceived ‘mothering’ roles,Reference Ashencaen Crabtree and Shiel4 which significantly detract from the time and focus needed to develop the metrics (publications and grant capture) that matter most in achieving highest levels of promotion. This is the end stage of the ‘leaky pipeline’ for women in academic medicine along the full passage from medical student to pro-vice-chancellor.

The academic environment is a socially constructed system, influenced by gender. Decisions as to who is the chief investigator on a grant application or senior author on a paper are rarely transparent, and often mired in gender-influenced communication and power positioning. Academic prominence requires personal attributes less often seen or promoted in women. Collaborative leadership styles, being a team player, having concerns about being seen as ‘difficult’ or the adverse impact that key decisions can have on others are not character qualities a traditional academic career requires for success. The lack of a sufficient number of role models (i.e. women in the highest positions in academic psychiatry), showing different ways to manage these tensions and still achieve, perpetuates fewer women entering academic careers.

Persistence of gender inequality in academic medicine, despite decades of gender equality in medical school placement, may no longer be the result of overt discrimination and may be more related to unconscious bias and structural issues. Women are more likely to have non-linear careers, have career breaks and caring responsibilities at crucial times when gaining academic momentum is essential in systems designed for linear metric-based progression. Networking, attending, and speaking at, national and international conferences, international exchanges and placements are also seen as key to gaining a ‘presence’ and leadership status. Although some conferences are recently promoting family-friendly values, and academic training fellowships now allow career breaks, this is small scale compared with the challenge of multiple caring roles and hard choices. Women can and do find complicated paths and solutions to fit in with structures and systems of academic medicine that have developed over decades to suit the lives of the male majority. However, it is interesting and pertinent to note that during the COVID-19 pandemic there have been reports of a dramatic drop in academic submissions by women;Reference Gabster, van Daalen, Dhatt and Barry5 the concern is that in the face of any significant challenge, the precarious nature of small, hard-fought advances in gender equality is laid bare.

Why does it matter?

The current inequality in academic publishing is a reflection of a male-dominated hierarchy that used to exist throughout medicine, and although much improvement has occurred in the clinical realm, this inequity remains within research structures. Given the challenge psychiatry still faces in making scientific advances, not enabling everyone with the talent and drive to contribute is short-sighted indeed. A society that is structured so that women do not achieve their potential is also not simply unjust; it is unwise. Empowerment of women throughout society, enabling the potential for equality in status, is essential to optimise productivity and advancement in research and to ensure that we are addressing all areas of mental health research to improve positive health and social outcomes.

Gender equality is, of course, just one issue needing to be addressed for full equality to be achieved. Direct action in all areas of discrimination is needed, with particular emphasis on intersectional discrimination (e.g. ethnicity and gender), which has a significant and compounded impact. Nonetheless, aiming to establish a workplace free of harassment is not enough. Junior clinical researchers of all genders aiming for this career path need to aspire and be inspired by senior female, male and non-binary figures. Male engagement with the issue of gender and race equality and equity is vital. Until we achieve equality at the top, men in senior positions need to be able to mentor and support junior researchers regardless of gender and ethnicity, rather than focusing support (for the majority unintentionally) on male juniors who may look ‘more like them’.

Position of the BJPsych

Although there are drivers to expedite change in academia, notably the Athena SWAN initiative, which promotes positive gender change through public ranking and reward in UK universities, the best way to achieve equality is not to focus on one metric (e.g. percentage of grant success, percentage of female professors, percentage of first and senior author papers in prestigious journals), but to address it from all sides with concerted and affirmative action. Our position at the BJPsych is to follow an explicit pathway of action to ensure that improvements in gender equality in publishing occur at an increased pace; we aim to put our own house in order first.

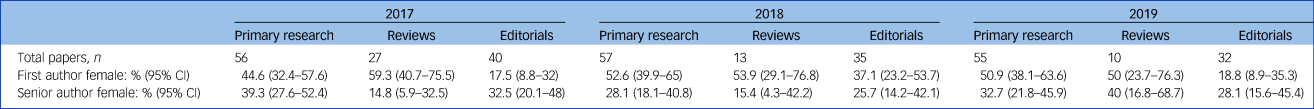

Author gender and other diversity data have not been routinely collected in BJPsych journals, as is the case in other academic journals to our knowledge. We conducted a preliminary, retrospective review of papers published in the BJPsych in the years 2017–2019, grouped by first and last author gender (Table 1). Although data are small in number, there appear to be differences by gender and potentially significant work to be done. Further reading on the topic is listed in the Appendix.

Table 1 Authorship by gender for papers published in the BJPsych 2017–2019 inclusive

Author contributions

All authors substantially contributed to the conception and drafting of the work. All authors have approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Declaration of interest

R.U. reports grants from the Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme, and personal fees from Sunovion, outside the submitted work. M.B. reports other funding from Oxford University Press, grants from the NIHR Clinical Research Network, personal fees from the Medical Defence Union, outside the submitted work. A.L.H. is an Associate Editor of Addiction. A.S. is the Managing Editor, R.U. and M.B. are Deputy Editors and A.d.C., D.T. and A.L.H. are on the editorial board of the BJPsych, but have not been involved in the peer review or handling of this manuscript.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.192.

Appendix

Further reading

Advance HE. Athena SWAN Charter. Advance HE, 2020 (https://www.ecu.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan/).

Berdahl JL. The sexual harassment of uppity women. J Appl Psychol 2007; 92: 425–37.

Breedvelt JJ, Rowe S, Bowden-Jones H, Shridhar S, Lovett K, Bockting C, et al. Unleashing talent in mental health sciences: gender equality at the top. Br J Psychiatry 2018; 213: 679–81.

Flaherty C. No room of one's own. Inside Higher Ed 2020; 20 Apr (https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/04/21/early-journal-submission-data-suggest-covid-19-tanking-womens-research-productivity).

Hosang GM, Bhui K. Gender discrimination, victimisation and women's mental health. Br J Psychiatry 2018; 213: 682–4.

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Ann Rev Sociol 2001; 27: 415–44.

Sen G, Östlin P. Gender inequity in health: why it exists and how we can change it. Glob Public Health 2008; 3: 1–12.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.