Studies on the incidence of schizophrenia have shown wide variation in their estimates, variations which cannot be attributed exclusively to methodological differences between studies (Reference McGrath, Saha and WelhamMcGrath et al, 2004). For example, recent investigations have consistently shown higher risk of psychosis for individuals brought up in urban centres, as compared to those from rural areas (Reference Krabbendam and van OsKrabbendam & van Os, 2005). Other studies have demonstrated high rates in migrants, particularly Black migrants to countries with predominantly White populations (Reference Cantor-Graae and SeltenCantor-Graae & Selten, 2005). Studies on the incidence of affective psychoses are much less frequent. However, the vast majority of these studies on the epidemiology of psychosis have been carried out in Europe or North America.

In Brazil, as in many low- and middle-income countries, marked demographic changes have taken place in recent decades, with population ageing and disorganised urbanisation (Reference CohenCohen, 2003). These changes may have had an impact on the incidence of psychosis, since there has been an increase in the adult population at risk and in possible risk factors, such as migration, as well as higher exposure to viruses and to adverse life events. There is a lack of empirical data on the incidence of schizophrenia and affective psychoses in such settings. The present study aimed to estimate incidence rates of first-contact psychosis in São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil.

METHOD

The setting

Greater São Paulo is one of the largest conurbations in the world, with a population of 19 million inhabitants, of which 11 million live in the city of São Paulo (Prefeitura do Município de São Paulo, 2006). São Paulo is the wealthiest city of Brazil, concentrating 10% of the national gross domestic product. As a consequence, it has attracted a large number of migrants from poorer areas of the country, and social inequalities are strong. The average Human Development Index is 0.81, ranking São Paulo as the 63rd best among 5507 cities and towns of Brazil. Infant mortality rate is 15 per 1000, but varies across city areas. Almost all inhabitants have piped water and rubbish collected, but nearly 1.2 million people live in slums termed ‘favelas’, and 10% of heads of households do not have any income of their own.

Mental healthcare in São Paulo is provided mainly by the public sector, and a small proportion of the population receives mental healthcare from the private sector. Mental healthcare in the public sector is partially organised on a catchment-area basis. Emergency 24-h psychiatric services can be sought by anyone who needs immediate attention, regardless of where they live. Inpatient care is provided by some public psychiatric hospitals and by private hospitals that offer psychiatric beds to the public sector on a fee-for-service basis. There is a central registry service that controls all admissions to psychiatric in-patient care paid for by the public sector in the city, except for a few beds in some public general hospitals with psychiatric in-patient units. For individuals suffering from psychosis, mental healthcare centres offer out-patient appointments with psychiatrists, and may deliver typical antipsychotic medication. A small proportion of patients may have access to psychotherapy, occupational therapy, social support or day-hospital care. A few primary care centres that have mental health professionals may offer care to adults with psychotic disorders. Private mental healthcare includes both exclusively private care, where all expenses are paid for by the client, and care provided by healthcare plans, where clients can only use services specified by the healthcare plan company. About 40% of the population are covered by private healthcare plans, and seek healthcare in private clinics and hospitals. However, until recently such plans did not cover psychiatric care. Fully paid in-patient psychiatric care is available in a small number of clinics and private hospitals. There are hundreds of psychiatrists in the city who offer private consultations, with a wide range of fees.

The area defined for the study was composed of 21 administrative districts, in the central, western and northern regions of the city, with a total population of 1 382 861 inhabitants in the year 2000 (Prefeitura do Município de São Paulo, 2006). This area includes residential middle-class regions, deprived inner-city areas, working-class residential regions, and areas of ‘favelas’. Mental health services that offer care for the public sector in the area include five 24-h emergency services, six mental health centres, four in-patient units in public hospitals, and five primary care centres with mental health professionals. There are three teaching hospitals, two of them from public universities, located in the area of the study. These hospitals have large psychiatric services, and access to care in these services does not follow geographical catchment-area restrictions.

Case identification and ascertainment

All mental health services, public or private, from which individuals living in the area defined might seek help for a psychotic episode, were screened to identify all possible cases of first-contact psychosis. This included the services listed above, plus the central registry service for psychiatric inpatient admissions paid for by the public sector, all private psychiatric hospitals and clinics in the city of São Paulo, and two psychiatric services from private healthcare plans. Over 300 psychiatrists who work privately, whose names and contacts were drawn from the Brazilian Psychiatric Association list, were contacted by post and by phone and asked to say whether they had seen first-contact patients who lived in the area defined for the study during the period specified below. Medical records of each service were browsed on a regular basis. Contact details of individuals with any suggestion of a consultation or admission due to psychotic symptoms were collected, because quite often it was not possible to establish whether it was a first contact or not from the medical records. Confirmation of first-contact had then to be made by phone or home visit.

Eligible individuals were all adults aged 18–64 years, resident in the defined geographical area of São Paulo for at least 6 months, who had a first contact with any mental health service due to a psychotic episode between 1 July 2002 and 31 December 2004. Participants had to meet DSM–IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) for psychotic disorder (295.10–295.90; 297.1; 298.8; 298.9; 296.0; 296.4; 296.24).

DSM–IV diagnoses were obtained for those who agreed to be interviewed, using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM–IV Axis I Disorders (SCID–I; Spitzer et al, 1992). For those who refused a direct assessment or for those who could not be directly contacted for other reasons, DSM–IV diagnoses were made based on information gathered from case notes and informants, wherever possible. Assessments were carried out as close as possible to the identification of each case in the mental health service. Interviews with participants took place at participants' homes, and were carried out by mental health professionals trained in the use of the standardised assessments. Training of interviewers included sessions for discussion of all standardised assessment schedules used in the study, and interview of patients with psychosis by each interviewer, watched by all remaining interviewers and coordinators of the study, followed by discussion. There was constant supervision of interviewers during the study, with discussion of difficulties and doubts in any of the schedules of the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

A leakage study was also carried out, in order to identify cases missed throughout the study period, and included surveillance of cases who had a first contact during the period of the study but were only found at a later date by the research team and review of casenotes of services not routinely visited by the research team.

Analysis

The total number of person-years at risk was calculated using the number of resident individuals aged 18–64 years living in the area defined for the study (926 081), according to data from the 2000 Census of the Brazilian population, multiplied by 2.5, to give the population at risk over the 30-month period of inclusion of cases. Overall, non-standardised incidence rates were estimated for first-contact psychosis (all diagnostic categories above), non-affective psychoses (DSM–IV codes 295.10–295.90; 297.1; 298.8; 298.9) and affective psychoses (DSM–IV codes 296.0; 296.4; 296.24). Respective binomial exact 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Age- and gender-specific incidence rates were also estimated, with 95% confidence intervals.

RESULTS

There were 172 participants who fulfilled criteria for first-contact psychosis and agreed to be included in the study. A further 60 individuals were identified as first-contact cases but refused to be interviewed, and another 135 cases were found through the leakage study. The types of service most frequently sought were the 24-h emergency services, where 67.3% of the cases had their first contact, followed by in-patient services (16.3%) and mental health centres with day care (10.3%). There were 187 women participants (51.0%). One hundred and forty-four (39.2%) participants fulfilled diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizophreni-form disorder, 88 (24.0%) for other non-affective psychoses (mostly brief psychotic disorder and non-specified psychotic disorder), 85 (23.2%) fulfilled criteria for bipolar disorder and 50 (13.6%) for depression with psychotic symptoms.

The mean age at first contact for any psychosis was 32.9 years (95%CI 31.7–34.1), and the median age was 30.0 years (Table 1). The average age at first contact for men was younger than for women, and the distribution of age at first contact was more positively skewed for men than for women. Similar patterns of skewness were observed for both non-affective and affective psychoses. Men showed mean and median ages at first contact for non-affective psychoses 4–5 years younger than for affective psychoses, whereas for women there were almost no differences between non-affective and affective psychoses.

Table 1 Mean and median ages at first contact for any psychosis, non-affective and affective psychoses by gender

| Women (n=187) | Men (n=180) | Total sample (n=367) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (s.d.) | median | mean (s.d.) | median | mean (s.d.) | median | |

| Any psychosis | 35.7 (11.8) | 34.0 | 30.0 (10.0) | 26.5 | 32.9 (11.3) | 30.0 |

| Non-affective psychoses | 36.0 (11.9) | 34.5 | 28.5 (8.9) | 26.0 | 31.8 (10.9) | 29.0 |

| Affective psychoses | 35.4 (11.9) | 34.0 | 33.8 (11.5) | 30.0 | 34.8 (11.7) | 34.0 |

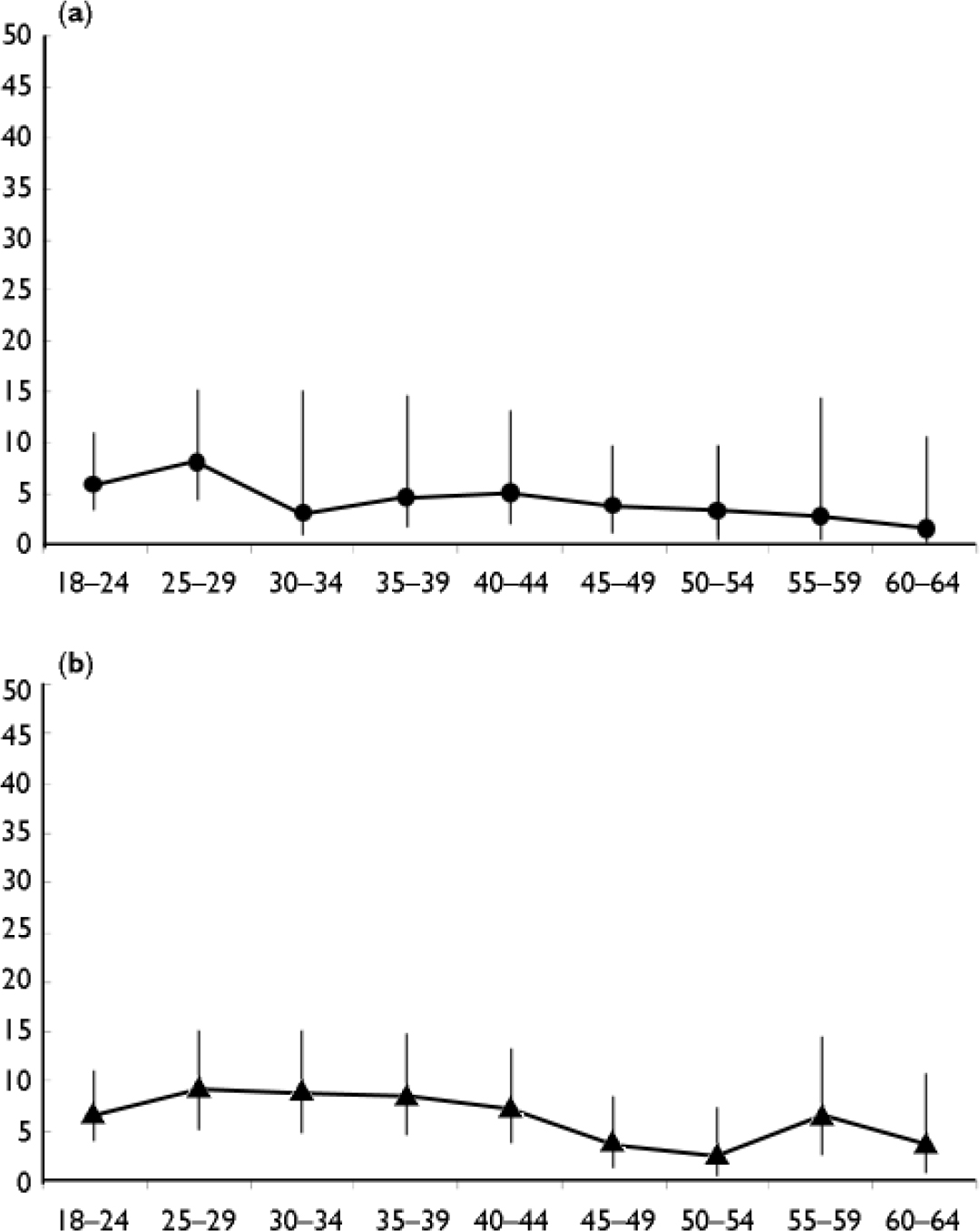

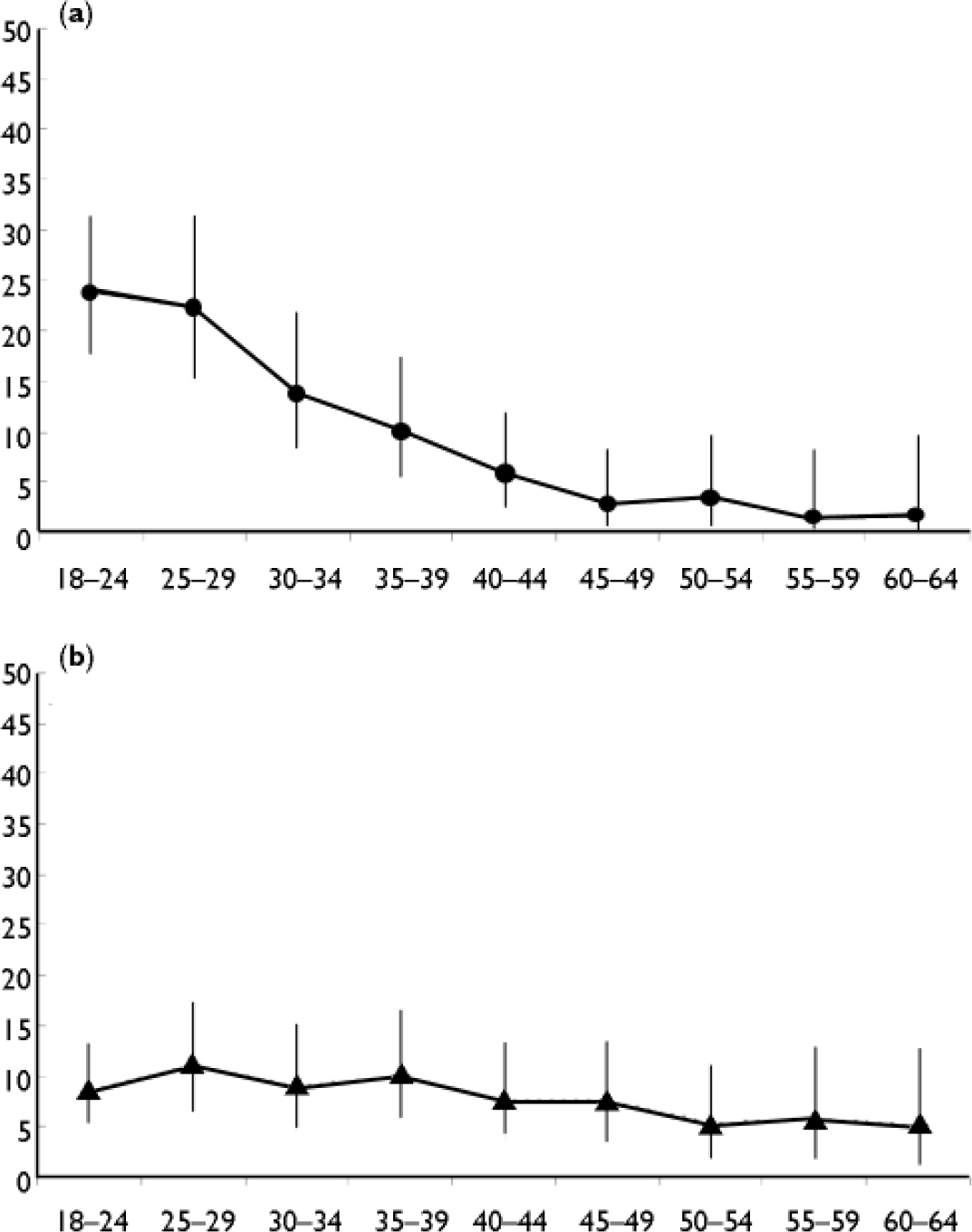

The unadjusted rate for first-contact psychosis was 15.8 per 100 000 person-years at risk (Table 2). Rates for non-affective and affective psychoses were 10.1 per 100 000 and 5.8 per 100 000, respectively. First-contact psychosis rates declined with increasing age; this was mostly due to rates of non-affective psychoses among the male population, which showed the highest rates in younger age groups followed by a sharp decline in older age groups (Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 2 Population at risk, number of cases (n) and incidence rates of first-contact psychosis, non-affective psychosis and affective psychosis by age group and total population

| Any psychosis | Non-affective | Affective | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, years | Population at risk | n | Incidence (95% CI) | n | Incidence (95% CI) | n | Incidence |

| 18-24 | 448 733 | 100 | 22.3 (18.1-27.1) | 71 | 15.8 (12.4-20.0) | 29 | 6.5 (4.3-9.3) |

| 25-29 | 306 708 | 77 | 25.1 (19.8-31.4) | 50 | 16.3 (12.1-21.5) | 27 | 8.8 (5.8-12.8) |

| 30-34 | 276 320 | 48 | 17.4 (12.8-23.0) | 31 | 11.2 (7.6-15.9) | 17 | 6.2 (3.6-9.9) |

| 35-39 | 277 188 | 47 | 17.0 (12.5-22.5) | 28 | 10.1 (6.7-14.6) | 19 | 6.9 (4.1-10.7) |

| 40-44 | 264, 115 | 35 | 13.3 (9.2-18.4) | 18 | 6.8 (4.0-10.8) | 17 | 6.4 (3.8-10.3) |

| 45-49 | 240 345 | 22 | 9.2 (5.7-13.9) | 13 | 5.4 (2.9-9.3) | 9 | 3.7 (1.7-7.1) |

| 50-54 | 205 495 | 15 | 7.3 (4.1-12.0) | 9 | 4.4 (2.0-8.3) | 6 | 2.9 (1.1-6.4) |

| 55-59 | 157 978 | 14 | 8.9 (4.8-14.9) | 6 | 3.8 (1.4-8.3) | 8 | 5.1 (2.2-10.0) |

| 60-64 | 138 323 | 9 | 6.5 (3.0-12.3) | 5 | 3.6 (1.2-8.4) | 4 | 2.9 (0.8-7.4) |

| Total | 2 315 203 | 367 | 15.8 (14.3-17.6) | 231 | 10.0 (8.7-11.4) | 136 | 5.9 (4.9-7.0) |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to estimate the incidence of first-episode psychosis in a large metropolis in Brazil. The rate of first-episode psychosis (15.8 per 100 000) was lower than expected for a large metropolis. For non-affective psychosis, the present rate is in the lower quartile of incidence estimates found in several studies in different settings (Reference McGrath, Saha and WelhamMcGrath et al, 2004). Incidence rates of schizophrenia for each participant centre in the World Health Organization (WHO) Ten-Country Study (Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992) and for three studies in Caribbean countries (Reference Hickling and Rodgers-JohnsonHickling & Rodgers-Johnson, 1995; Reference Bhugra, Hilwig and HosseinBhugra et al, 1996; Reference Mahy, Mallett and LeffMahy et al, 1999), calculated using CATEGO S+ and SPO diagnoses, varied from 9 to 35 per 100 000. Reanalysis of longitudinal data from two centres in the WHO Ten-Country Study generated estimates based on ICD–10 criteria for F–20 schizophrenia, which varied from 14 per 100 000 in Nottingham to 42 per 100 000 in rural Chadigarh (Reference Bresnahan, Menezes, Varma, Murray, Jones and SusserBresnahan et al, 2003). In the ÆSOP study (Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006), carried out in three centres of the UK (London, Nottingham and Bristol), incidence rates for all first-contact psychoses, non-affective and affective psychoses were higher than in the present study. This was mostly due to much higher rates for non-affective and affective psychoses in London, rates from Nottingham and Bristol being similar to those reported in the present study. For affective psychosis, comparison is more difficult, since most studies did not estimate rates for bipolar disorder and depressive psychosis together. Taking that into account, the present figures for the incidence of affective psychoses are similar to those from the ÆSOP study (Reference Lloyd, Kennedy and FearonLloyd et al, 2005; Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006). Rates were higher for men than for women in our study, following the pattern observed in a systematic review of studies on the incidence of schizophrenia (Reference McGrath, Saha and WelhamMcGrath et al, 2004), and in the studies on the incidence of psychosis in the UK (Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006) and rural Ireland (Reference Scully, Quinn and MorganScully et al, 2002). This was mostly due to higher incidence of non-affective psychoses among younger men, whereas rates for affective psychoses were similar for both genders.

Age at first contact also followed patterns observed previously (Reference van Os, Driessen and Gunthervan Os et al, 2000; Reference Boydell, van Os and McKenzieBoydell et al, 2001; Reference Svedberg, Mesterton and CullbergSvedberg et al, 2001; Reference Scully, Quinn and MorganScully et al, 2002; Reference Welham, Thomis and McGrathWelham et al, 2004; Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006). More than 60% of the cases had their first contact before the age 35, confirming that psychosis is more frequent in young adults, but a proportion of cases can occur at older ages. Men had younger mean and median ages at first contact than women for both affective and non-affective psychoses, a finding also consistent with results from some recent studies carried out in high-income countries (Reference Svedberg, Mesterton and CullbergSvedberg et al, 2001; Reference Scully, Quinn and MorganScully et al, 2002; Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006). However, comparison of mean or median age at first contact between studies is not straightforward, since there is variation in the age range criterion used in each study. Some studies have used the age range 15–45 or 15–54 years, which will influence their samples towards younger age means, whereas those that have wider age ranges, particularly for the upper limit, will tend to find older sample means. Comparison of age- and gender-specific incidence rates is less subject to such methodological issues. However, few studies yielded age- and sex-specific incidence rates for both affective and non-affective psychoses, making comparison of results limited. Age- and gender-specific rates from the present study are lower than those found in the UK (Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006), but rates in that study were influenced upwards by the uncommonly high rates found in South London. A recent study carried out in Queensland, Australia (Reference Welham, Thomis and McGrathWelham et al, 2004) also estimated age- and gender-specific incidence rates for affective and non-affective psychoses, and results from both studies are remarkably similar.

Limitations and implications

The incidence rate of first-contact psychosis may have been underestimated. It is possible that a small proportion of first-contact psychosis cases were not identified due to missing files, lack of any notes that could allow checking for possible diagnosis or address, or because they were not living at the address provided. Use of private psychiatric services not covered by the present study, and non-inclusion of psychoses due to intoxication or withdrawal of psychoactive substances may also have contributed to the low rates. However, these cases only accounted for small proportion of the total number of cases of psychosis in two recent studies (Reference Scully, Quinn and MorganScully et al, 2002; Reference Kirkbride, Fearon and MorganKirkbride et al, 2006). It is unlikely that the low incidence rates might be due to non-detection of cases owing to premature death or to moves to other areas of the city. The main cause of premature death among individuals with psychosis is suicide (Reference Craig, Ye and BrometCraig et al, 2006). However, suicide rates in São Paulo are much lower than those observed in high-income countries (Reference Mello-Santos, Bertolote and WangMello-Santos et al, 2005). Moving house because of psychotic breakdown is also unlikely, since around 80–90% of those with psychosis in São Paulo live with their relatives and most rely entirely on their families to survive (Reference Menezes and MannMenezes & Mann, 1993). Therefore, even if our rates may be slightly underestimated, we nevertheless believe that we have identified the vast majority of cases. Non-systematic errors regarding diagnosis may have happened, but are not likely to explain the patterns observed. The areas covered by the study were heterogeneous regarding socio-economic status of the population, but there are large parts of the city with higher proportions of more deprived areas. This means that if the incidence of psychosis varies within city areas, and if this variation is associated with neighbourhood socio-economic levels, the present rates may be also slightly underestimating the overall rates for the metropolis.

Fig. 1 Incidence rates of non-affective (a) and affective (b) psychoses by age group among women.

Fig. 2 Incidence rates of non-affective (a) and affective (b) psychoses by age group among men.

We did not examine the possible association between incidence of psychosis and ethnicity. One of the marked characteristics of the Brazilian population is its ethnic admixture. According to the Brazilian Census, which uses self-reported skin colour or ethnicity, in the State of São Paulo 71% of the population classify themselves as white, 4% as black, and 23% as mixed (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2006). Genetic studies also have shown that in Brazil, ethnic phenotypes do not allow adequate classification of ethnic ancestry, because of the high levels of admixture (Reference Parra, Amado and LambertucciParra et al, 2003). Therefore, the Brazilian population is not adequate to explore comparisons of incidence of psychosis by ethnic group. However, modern genotyping techniques are allowing more precise measurement of the amount of different genetic ethnic ancestries in individuals, and these techniques could be used to examine possible associations between degree of admixture and risk of psychosis, using a case–control design.

The studies on the outcome of schizophrenia coordinated by the WHO showed a better prognosis among those with psychosis living in lower- and middle-income societies (Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992). If the relatively low incidence rates observed in the present study are followed by a high proportion of recovery, then a low prevalence of psychosis would also be expected, and that might have an impact on planning and provision of mental health services. However, more recently the notion of a better outcome of psychosis in lower- and middle-income countries has been disputed, based on some methodological limitations of the WHO studies, the lack of evidence for specific sociocultural factors that might contribute to a better prognosis of psychosis, new data showing a gloomier picture for the prognosis of psychosis in some lower- and middle-income societies, and on important economic and demographic changes that are taking place in many lower- and middle-income countries (Reference Patel, Cohen and TharaPatel et al, 2006). Indeed, São Paulo follows more closely the patterns of living conditions and social demands found in industrialised societies, and therefore the prognosis of psychosis may not be a favourable one. Follow-up of the present first-contact cohort will help to answer this issue.

Recent studies are helping to show how the observed variation in incidence rates between different ethnic or social groups may be at least partly explained by heterogeneous distribution of psychosocial risk factors (Reference Wicks, Hjern and GunnellWicks et al, 2005; Reference Morgan, Kirkbride and LeffMorgan et al, 2006). Similar investigations in different settings (large and smaller urban centres, rural areas) from lower- and middle-income countries must be carried out in order to contribute to a better understanding of the determinants of the incidence of these disorders.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the research staff involved in the field work of this study, all institutions and psychiatrists that allowed access to medical records and patients, and the University Hospital of the University of São Paulo. P.R.M. and M.S. are partly funded by CNPq-Brazil. The present work was funded by The Wellcome Trust.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.