The Early Detection and Intervention programme of the German Research Network on Schizophrenia (GRNS) was established in 2000 to promote research on the initial prodromal phase of psychosis. Early Detection and Intervention Centres at the outpatient departments of four university hospitals (Bonn, Düsseldorf, Munich and Cologne) are collaborating in intervention studies with Cologne acting as the coordinating centre.

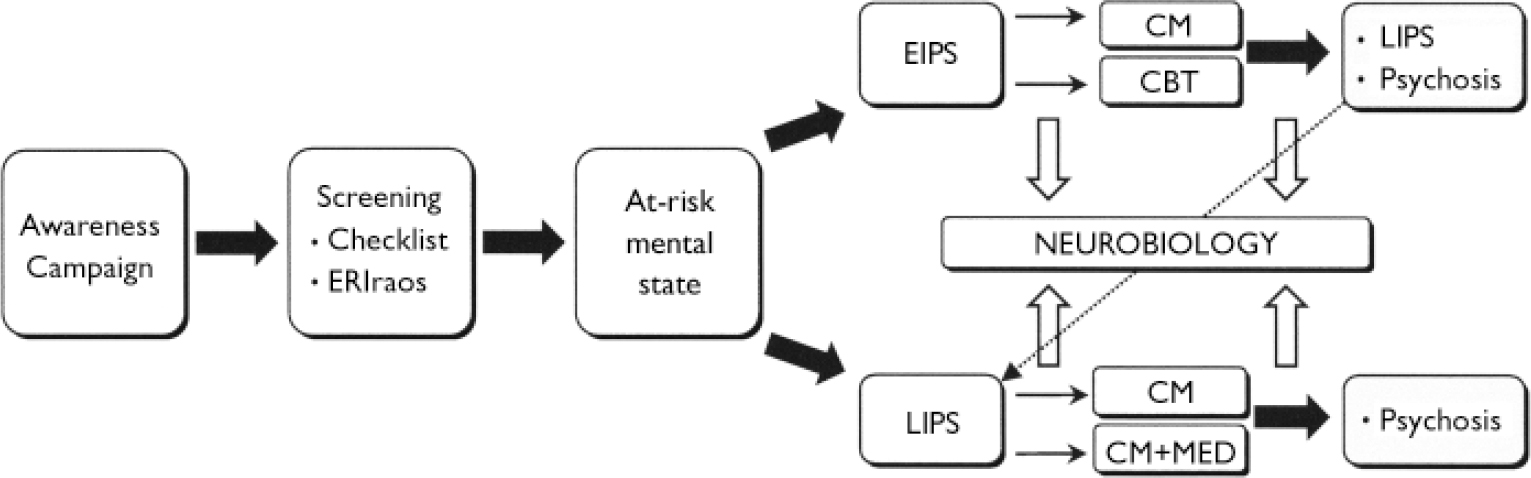

An awareness programme (Reference Köhn, Berning and MaierKöhn et al, 2002) is ongoing for psychiatric and primary healthcare services, families of patients with schizophrenia, several youth support services and the general population. It provides information about early symptoms of schizophrenia and the need for early intervention. The aims of the programme are to promote help-seeking help-seeking and engagement with early intervention services for individuals at-risk of psychosis.

A two-step approach has been created in order to identify individuals at-risk for psychosis. A checklist (Reference Häfner, Maurer and RuhrmannHäfner et al, 2004) has been used which serves as a low-threshold screening instrument for people who have approached general practitioners or counselling services, etc. because of mental health problems. The checklist includes criteria which indicate that a contact or a referral to one of the early intervention centres should be made. At the centre, a detailed assessment is made using a specially designed instrument, the Early Recognition Inventory (ERIraos; Reference Maurer, Hörrmann and SchmidtMaurer et al, 2004). The ERIraos indicates whether the individual at-risk of psychosis is in an ‘early initial prodromal state’ or a ‘late initial prodromal state’ (see below), as defined by the GRNS.

When there is evidence of an early initial prodromal state (EIPS), the at-risk individual is invited to participate in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) on psychological early intervention. However, an at-risk person with evidence of a late initial prodromal state (LIPS) is asked if they will take part in an RCT with pharmacological intervention, using amisulpride. In addition to psychopathological and psychosocial psychosocial assessments, individuals are asked to take part in GRNS neurobiological research projects. These comprise neuropsychological and neurophysiological assessments, brain imaging and molecular genetics (Reference Maier, Wagner and FalkaiMaier et al, 2002). Furthermore, the effect of the awareness programme is investigated by pre- and post-assessments and comparison with regions in which the awareness programme does not operate (Reference Köhn, Berning and MaierKöhn et al, 2002) (Fig. 1). Each study was approved by the respective local ethics committees.

Fig. 1 Overview of the Early Detection and Intervention programme of the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. ERIraos, Early Recognition Inventory; EIPS, early initial prodromal state; LIPS, late initial prodromal state; CM, clinical management; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; MED, antipsychotic medication.

INTERVENTIONS IN THE INITIAL PRODROMAL STATES

The EIPS is defined by: (a) the presence of certain self-experienced cognitive thought and perception deficits (‘basic symptoms’ according to Reference Huber and GrossHuber & Gross, 1989), which were found to be predictive for transition to psychosis in 70% of the cases within 5 years (Reference Klosterkötter, Hellmich and SteinmeyerKlosterkötter et al, 2001); and/or (b) by the presence of a clinical decline in functioning in combination with well-established risk factors (Reference Yung, Phillips and McGorryYung et al, 1998) (see Appendix for details). Estimating the risk/benefit ratio of intervening in the EIPS, a comprehensive cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) programme was developed (Bechdolf et al, Reference Bechdolf, Maier and Knost2003, Reference Bechdolf, Phillips and Francey2005b ) which has been influenced by the work of other investigators in this field (e.g. Reference Kingdon and TurkingtonKingdon & Turkington, 1994; Reference Fowler, Garety and KuipersFowler et al, 1995; Reference Chadwick, Birchwood and TrowerChadwick et al, 1996). CBT can be useful in the early initial prodromal state, in particular because it is readily accepted by patients and little stigma is attached. Also, there is no risk of exposing false-positives to possible pharmacological side-effects. Since the efficacy of CBT in schizophrenia has been established for persistent psychotic symptoms in a number of investigations (see meta-analyses by Reference Rector and BeckRector & Beck, 2001; Reference Gould, Mueser and BoltonGould et al, 2002; Reference Pilling, Bebbington and KuipersPilling et al, 2002; Reference Cormac, Jones and CampbellCormac et al, 2003), one could hypothesise that such an approach is also effective in the prepsychotic phase. Moreover, CBT is an established treatment for anxiety, depression and several other syndromes, which are often present at this stage.

The LIPS criteria are similar to the ‘ultra-high-risk’ measures used by current controlled intervention studies (Reference McGorry, Yung and PhillipsMcGorry et al, 2002; Reference Woods, Breier and ZipurskyWoods et al, 2003; Reference Morrison, French and WalfordMorrison et al, 2004) (Appendix). Patients fulfilling LIPS criteria are highly symptomatic, functionally compromised (Reference Miller, Zipursky and PerkinsMiller et al, 2003) and have a risk between 36% and 54% of developing psychosis within 12 months (Reference Miller, McGlashan and RosenMiller et al, 2002; Yung et al, Reference Yung, Phillips and Yuen2003, Reference Yung, Phillips and Yuen2004; Reference Mason, Startup and HalpinMason et al, 2004). Taking this into account and also the significantly improved tolerability of the new neuroleptics, it seemed appropriate to investigate the possible benefits of pharmacological interventions for these patients. In the LIPS study, amisulpride was chosen for several reasons: at a low dose there are beneficial effects on depressive and negative symptoms, probably because of its primarily dopaminergic properties in the low-dosage range. At a higher dose it is an effective antipsychotic and data from schizophrenia studies lead us to anticipate very good tolerability with a side-effect rate no different from placebo at low doses and, not least, low weight gain (Reference Ruhrmann, Schulze-Lutter and KlosterkötterRuhrmann et al, 2003).

Aims of both intervention studies are: (a) improvement of present prodromal symptoms; (b) prevention of social decline/stagnation; and (c) prevention or delay of progression to psychosis.

Intervention in the EIPS

Design

Patients meeting EIPS criteria are randomised to receive either comprehensive CBT treatment or clinical management for 12 months. Interventions in both conditions follow a detailed manual, which defines the aims of the sessions, examples of interventions and gives model responses for the therapist (Reference Bechdolf, Knost and MaierBechdolf et al, 2002). The recruitment period is 3 years. Assessments take place pre- and post-treatment (12 months) and at 24-month follow-up. After the intervention period, monthly telephone interviews are conducted to check if there is transition to psychosis. Main rating instruments are the Early Recognition Inventory (ERIraos; Reference Maurer, Hörrmann and SchmidtMaurer et al, 2004), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Reference Kay, Fiszbein and OplerKay et al, 1987), DSM–IV Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF–F; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Reference Montgomery and ÅsbergMontgomery & Åsberg, 1979). At yearly intervals, the Social Adjustment Scale–II (SAS–II; Reference Schooler, Hogarty, Weissman and HargreavesSchooler et al, 1979) is administered. Transition to psychosis is defined by commonly used criteria (e.g. Reference McGorry, Yung and PhillipsMcGorry et al, 2002; Reference Morrison, French and WalfordMorrison et al, 2004), such as the presence of at least one psychotic symptom from a list for brief limited intermittent psychiatric symptoms (BLIPS, see Appendix) for longer than 6 days. In accordance with our differential intervention approach the presence of inclusion criteria for the LIPS served as additional exit criteria from the EIPS intervention trial.

CBT intervention

The experimental intervention is based on a CBT model (Reference Larsen, Bechdolf and BirchwoodLarsen et al, 2003). Individual therapy forms the central part of the early intervention programme. A combination of psychoeducation, symptom, stress and crisis management modules is adapted to the specific needs of each client. Although putative prepsychotic symptoms serve as inclusion criteria for therapy, the interventions are problem-oriented, collaborative, educational and involve the therapist and the client working together on an agreed problem list. This may also include problems other than basic symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, family or occupational problems. Apart from the treatment of the psychopathological symptoms, one major treatment aspect focuses on attributional styles that underpin symptoms. Psychoeducation and cognitive techniques are used to challenge self-stigmatisation and self-stereotypes, helping the person to protect and enhance self-esteem, and to come to terms with understanding the illness and pursuing life goals. A special group intervention, cognitive remediation and a short psychoeducational multi-family intervention are also parts of the programme (Table 1).

Table 1 Psychological intervention in the early initial prodromal state

| Module | Topics |

|---|---|

| Individual therapy (30 Sessions) | Assessment and engagement |

| Psychoeducation | |

| Stress management | |

| Symptom management | |

| Crisis management | |

| Group therapy (15 Sessions) | Positive mood and enjoyment |

| Social skills | |

| Problem-solving | |

| Cognitive remediation (12 Sessions) | Concentration, attention, vigilance and memory |

| Information and counselling of relatives (3 Sessions) | Psychoeducation of multi-family group |

Intervention in the LIPS

Design

The LIPS project is a pharmacological phase III study conforming to good clinical practice and has a controlled, open-label, randomised, parallel group design. In the first condition, patients receive a psychologically advanced clinical management programme, including, where necessary, crisis intervention, family counselling, etc. Its primary aim is providing very focused, supportive care for the patient's acute needs (psychotherapy is not allowed). In the second condition, similar clinical management is combined with amisulpride. The dose can range between 50 mg and 800 mg per day, the increase in dose follows an algorithm based on clinical improvement and minimal time periods between changes of dosage. The treatment period is 2 years with weekly visits during the first 4 weeks, then bi-weekly until week 12, and monthly, thereafter.

Main rating instruments are ERIraos, PANSS, GAF–F and, at yearly intervals, SAS–II. Among other instruments are the MADRS, the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS; Reference Chouinard, Ross-Chouinard and AnnableChouinard et al, 1980) and the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU; Reference Lingjaerde, Ahlfors and BechLingjaerde et al, 1987).

RECRUITMENT

Between 1 January 2001 and 31 March 2003, 1212 individuals who were seeking help for mental health problems were examined using the checklist. This was administered by general practitioners, counselling services, psychiatrists and psychotherapists in private practice, psychiatric out-patient units at hospitals or the early intervention centres themselves. A total of 994 individuals fulfilled criteria for further assessment at the early recognition and intervention centres – 993 out of 994 were assessed. A total of 388 individuals fulfilled at-risk criteria. Of these, 190 fulfilled early initial prodromal state criteria and 109 (57.4%) gave informed consent to participate in the psychological intervention study. A total of 198 individuals met late initial prodromal state criteria and 79 (39.9%) gave informed consent to participate in the pharmacological intervention study. The main reasons why individuals fulfilling at-risk criteria were not included in the trials were: continued substance misuse, pre-treatment with neuroleptics, past history of psychotic episodes, refusing enrolment in research studies, refusing psychopharmacological treatment, living out of the catchment area, moving out of the area.

DISCUSSION

The Early Detection and Intervention programme of the GRNS investigates the initial prodromal phase of psychosis in a multidimensional approach including two intervention studies.

In the first 2 years of the project over 1200 help-seeking individuals were screened for at-risk mental state and almost 190 patients in the initial prodromal phase were recruited and assessed with regard to psychopathology, psychosocial and neurobiological parameters at four recently established Early Detection and Intervention centres. With almost 50% of the at-risk individuals, a high number of participants have been recruited for the psychological and pharmacological intervention trials.

Baseline assessments within the two studies indicated that help-seeking individuals with prodromal symptoms, who were randomised to receive a clinical intervention, were clinically symptomatic and functionally compromised (Reference Ruhrmann, Schulze-Lutter and KlosterkötterRuhrmann et al, 2003; Reference Häfner, Maurer and RuhrmannHäfner et al, 2004; Reference Bechdolf, Veith and StammBechdolf et al, 2005a ). First interim evaluations of both interventions are promising as the two approaches seem to be successful regarding the first two aims of the interventions: (1) improvement of early or late prodromal symptoms; and (2) improvement of social or occupational functioning (Reference Ruhrmann, Schulze-Lutter and KlosterkötterRuhrmann et al, 2003; Reference Häfner, Maurer and RuhrmannHäfner et al, 2004; Reference Bechdolf, Veith and StammBechdolf et al, 2005a ). A preliminary analysis of the EIPS study indicated advantages of CBT regarding transition to late initial prodromal state and psychosis (Reference Häfner, Maurer and RuhrmannHäfner et al, 2004).

In summary, the GRNS Early Detection and Intervention programme, including awareness campaigns and a two-stage screening approach, appears to be feasible and effective in recruiting at-risk individuals with putatively prodromal symptoms for interventions in the initial prodromal phase. The programme will be completed by the end of 2005 and will provide a sound data-set regarding the efficacy of intervening in the initial prodromal state, the prediction of psychosis, putative underlying neurobiological variables and the effects of awareness campaigns.

APPENDIX

Inclusion criteria for intervention studies on the early initial prodromal state and the late initial prodromal state

Early initial prodromal state

One or more of the following basic symptoms appeared in the last 3 months, several times a week:

-

• Thought interference

-

• Thought perseveration

-

• Thought pressure

-

• Thought blockage

-

• Disturbances of receptive language, either heard or read

-

• Decreased ability to discriminate between ideas and perception, fantasy and true memories

-

• Unstable ideas of reference (subject-centrism)

-

• Derealisation

-

• Visual perception disturbance

-

• Acoustic perception disturbance

and/or

Reduction in the DSM–IV Global Assessment of Functioning score of at least 30 points (within the past year) and at least one of the following risk factors:

-

• First-degree relative with a lifetime diagnosis of schizophrenia or a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder.

-

• Pre- or perinatal complications.

Late initial prodromal state

Presence of at least one of the following attenuated psychotic symptoms (APS) within the last 3 months, appearing several times per week for a period of at least 1 week:

-

• Ideas of reference

-

• Odd beliefs or magical thinking

-

• Unusual perceptual experiences

-

• Odd thinking and speech

-

• Suspiciousness or paranoid ideation

and/or

Brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms (BLIPS), defined as appearance of one of the following psychotic symptoms for less than 1 week (interval between episodes of at least 1 week), resolving spontaneously:

-

• Hallucinations

-

• Delusions

-

• Formal thought disorder

-

• Gross disorganised or catatonic behaviour

Exclusion and exit criteria

APS or BLIPS (early initial prodromal state).

Present or past diagnosis of a schizophrenic, schizophreniform, schizoaffective, delusional or bipolar disorder according to DSM–IV.

Present or past diagnosis of a brief psychotic disorder according to DSM–IV with a duration equal to or of more than 1 week or within the last 4 weeks regardless of its duration.

Diagnosis of delirium, dementia, amnestic or other cognitive disorder, mental retardation, psychiatric disorders due to a somatic factor or related to psychotropic substances according to DSM–IV.

Alcohol or drug misuse within the last 3 months prior to inclusion according to DSM–IV.

Diseases of the central nervous system (inflammatory, traumatic, epilepsy, etc.).

Aged <18 years and <36 years.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ A programme including awareness campaigns and a two-stage screening approach seems to be feasible and effective in recruiting at-risk individuals with putative prodromal symptoms for interventions in the initial prodromal phase.

-

▪ For patients presenting with psychosis-predictive basic symptoms and/or a clinically relevant decline of social functioning in combination with established risk factors (early initial prodromal state) a comprehensive cognitive – behavioural therapy (CBT) was developed, which is evaluated in comparison with clinical management in a randomised controlled trial (RCT).

-

▪ In patients presenting with attenuated and transient psychotic symptoms (late initial prodromal state) an RCT is being conducted comparing amisulpride and clinical management and clinical management alone.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Of the population identified with an at-risk mental state, 51.5% did not participate in the related RCTs.

-

▪ First results of both treatment approaches have to be cautiously interpreted, as they are based on preliminary data obtained from early interim analysis.

-

▪ Because the two large-scale RCTs are ongoing no final results can be presented.

Acknowledgements

The studies are part of the German Research Network on Schizophrenia which is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research BMBF (grant 01 GI 9935).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.