Recovery in psychosis has traditionally been defined within a biomedical framework based on symptom remission, decreased hospital admissions or relapse, 1 or operationally defined as a return to functioning in the normal range. Reference Torgalsboen2 These approaches to understanding and defining recovery have received criticism in recent years for not taking into account the ‘consumer’ perspective. Reference Bellack3 People using mental health services define recovery as a personal journey or process, Reference Deegan4,Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison5 often characterised by themes including hope, empowerment and social support. Reference Deegan4–Reference Ridgeway8 Recent cross-sectional research has investigated factors associated with subjective recovery and improved quality of life, demonstrating a significant role for psychosocial factors including negative emotion. Reference Morrison, Shyrane, Beck, Heffernan, Law and McCusker9 However, little is known about the role of negative emotion and psychosocial factors in predicting subjective recovery or variation in subjective recovery scores over time. Our longitudinal study aimed to investigate predictors of subjective recovery, with a particular focus on the role of negative emotion; based on an a priori theoretical model, our hypothesis was that recovery scores at 6 months would be predicted by recovery score and negative emotion at baseline.

Method

A convenience sample of participants was recruited from early intervention teams, community mental health teams, in-patient settings and voluntary services across the north-west of England. Participants were included in the data-set if they were aged 16–65 years, had a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder, had sufficient understanding of the English language to allow them to complete the measures and had the capacity to provide informed consent. A total of 174 participants were assessed at baseline and 171 participants were assessed at the 6-month follow-up point. The average age of participants was 37.3 years (s.d. = 11.62) and the majority of participants were White British (83.6%). Diagnoses at referral were schizophrenia (n = 50), schizoaffective disorder (n = 13), persistent delusional disorder (n = 7), unspecified non organic psychosis (n = 4) and acute and transient psychotic disorder (n = 2). The remaining 30 participants had not been given a diagnosis but were experiencing psychosis. Participants were recruited from early intervention services (n = 27), community-based mental health teams (n = 45) and an in-patient service (n = 1). Data on service type at referral were missing for 37 participants.

Measures

Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery

The Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) is a self-report measure which was developed collaboratively by a team of service user researchers and clinicians. Reference Neil, Kilbride, Pitt, Nothard, Welford and Sellwood10,Reference Law, Neil, Dunn and Morrison11 Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Reference Deegan4 Higher scores on the measure are indicative of subjective recovery. The brief 15-item version of the QPR was used in this study. Reference Law, Neil, Dunn and Morrison11 Cronbach's alpha for our sample was 0.947. Examples of the highest-loading items in the QPR include ‘I can actively engage with life’, ‘I can take charge of my life’ and ‘I feel part of society rather than isolated’. The QPR measures specific, recovery-related emotional constructs and so was expected to be strongly related with general measures of emotional functioning. They are not the same, however; using confirmatory factor analysis, Morrison et al found recovery beliefs measured by the QPR to be empirically distinct from general negative emotion (i.e. anxiety, depression and negative self-esteem) in a sample of psychiatric patients diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Reference Morrison, Shyrane, Beck, Heffernan, Law and McCusker9

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a 30-item semi-structured clinical interview comprising 7 items assessing positive symptoms (such as hallucinations and delusions), 7 assessing negative symptoms (such as blunted affect and emotional withdrawal) and 16 assessing global psychopathology (such as anxiety, guilt and depression). Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler12 All items are rated from 1 (not present) to 7 (severe). The PANSS has been used in a variety of studies and has been shown to have good reliability and validity. Reference Kay, Opler and Lindenmayer13

Personal and Social Performance

The Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scale is a measure of functioning rated by an observer across four domains: socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care and aggression. Reference Morosini, Magliano, Brambilla, Ugolini and Pioli14 The scale has been shown to have adequate internal consistency (α = 0.76). Reference Kawata and Revicki15 Total scores range from 1 to 100, with 100 indicating no functional difficulty. Most participants were rated for functioning using this scale, but a few (n = 27) were rated instead with the functioning subscale of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Reference Hall16 another measure of functioning that is used by an observer to rate symptoms and social, psychological and occupational functioning. Again, scores range from 1 to 100, with 100 representing no functional difficulty.

Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia

The Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) comprises 9 items each rated on a three-point Likert scale. Reference Addington, Addington and Schissel17 Global scores range from 0 to 27. The scale measures items on depression, hopelessness, self-depreciation, guilty ideas of reference, pathological guilt, morning depression, early wakening, suicide and observed depression.

Beck Hopelessness Scale

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) is a 20-item self-report measure designed by clinicians to measure three dimensions of hopelessness: feelings about the future, loss of motivation and expectations. Reference Beck, Weissman, Lester and Trexler18 Statements are rated by participants as true or false for their attitudes over the past week. The psychometric properties of the BHS have been examined in various studies and the measure has shown good reliability and validity. Reference Nunn, Lewin, Walton and Carr19–Reference Young, Halper, Clark, Scheftner and Fawcett21

Self Esteem Rating Scale

The short form of the Self Esteem Rating Scale (SERS) is a 20-item self-report measure assessing both positive and negative beliefs about the self. Reference Lecomte, Corbiere and Laisne22 Items are rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always’. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency and reliability and adequate convergent validity. Reference Lecomte, Corbiere and Laisne22

Procedure

Data were collected as part of a programme of research funded by the UK National Institute of Health Research. Individual studies within this research programme were approved by the research ethics committee involved. Recruitment took place across early intervention teams, community mental health teams, in-patient settings and voluntary services across the Greater Manchester area to ensure heterogeneity of service provision and experience of psychosis. Potential participants were approached by the care team and offered information about the study. Interested participants were given a minimum of 24 h to read the participant information sheet and decide whether to take part. Those who agreed to do so met with a researcher to complete a consent form and baseline study measures. The researcher then contacted participants 6 months later to repeat the set of measures in a follow-up assessment. Participants were recompensed for their time.

Statistical analysis

Path analysis was conducted to examine potential predictors of recovery scores and negative emotion. All path models were fitted in Mplus version 7 and estimated by maximum likelihood. Standard errors were estimated using the Huber–White sandwich estimator, which is robust to non-normality and heteroscedasticity in the outcome variables. Model log-likelihoods and the likelihood ratio tests were computed using Satorra–Bentler adjustments for non-normality. Nested models were compared using Satorra–Bentler corrected likelihood ratio chi-squared tests. Data from 110 participants who completed all measures in the model were included in the final path analysis. Data from 64 participants were excluded owing to missing or incomplete data-sets; these participants were not significantly different at baseline assessment from those who were included in the final analysis. The path analysis models were based on over 200 observations.

Model variables

Variables were assessed at baseline (time 1) and at 6-month follow-up (time 2). The sample was too small for adequate latent constructs; instead, scale composites were constructed to represent symptoms of psychosis (based on PANSS scores) and negative emotions (based on negative self-esteem and the Calgary scale). Reliability was generally good for these composites: PANSS α = 0.84 (time 1 only, α = 0.75; time 2 only, α = 0.73); negative emotions α = 0.82 (time 1 only, α = 0.72; time 2 only, α = 0.60). The reliability for negative emotion at time 2 was low. However, this reliability was based on just two items and was therefore considered acceptable. Core variables were recovery and negative emotion. Recovery consisted of the 15-item total QPR score. Negative emotion was a composite variable constructed by taking the mean of scores from the CDSS and the SERS negative subscale. The latter is scored from 10 to 70 whereas the CDSS is scored from 0 to 27. To avoid the composite measure being dominated by the higher scores of the SERS subscale, its raw scores were divided by 7 before taking the composite mean, which gave both contributing scales similar means and standard deviations.

Test variables included symptoms, hopelessness, positive self-esteem and functioning. Symptoms consisted of a composite variable representing the overall mean of the 7 positive, 7 negative and 16 general PANSS scale items. Hopelessness used the total score from the BHS. Positive self-esteem used the total score from the positive subscale of the SERS. Functioning used the functioning score of the PSP scale if available and the functioning subscale of the GAF if not. For the small number of participants (n = 34) who completed both the GAF and the PSP in this study, the correlation between these variables was impressive (r = 0.79). This is congruent for the theoretical expectations for these scales, with previous research suggesting a high correlation between GAF and PSP scores. Reference Juckel and Morosini23

Exogenous covariates measured at time 1 included age, education or employment, marital status, religious beliefs and early intervention. All covariates except age were binary variables coded as 1 for a positive response (i.e. in education or employment; married or living with a common-law spouse; belief in the existence of a deity; and recruitment from an early intervention service) and 0 for a negative response. These covariates were included to allow consideration of the effects of demographic and other potential confounding factors that were available within the data-set.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Table 2 summarises participants' scores from the baseline and 6-month follow-up assessments.

Table 1 Participant characteristics (n = 110)

| Variable | % | n |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 69 | 76 |

| Female | 31 | 34 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 84 | 92 |

| Asian | 8 | 9 |

| Black | 5 | 5 |

| Mixed | 4 | 4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 78 | 86 |

| Married | 11 | 12 |

| Separated | 11 | 12 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 7 | 8 |

| Unemployed | 76 | 84 |

| Student | 3 | 3 |

| Volunteer | 10 | 11 |

| Retired | 4 | 4 |

| Religious belief | ||

| None | 35 | 39 |

| Christian | 32 | 35 |

| Muslim | 11 | 12 |

| Other | 22 | 24 |

Table 2 Participant scores for key measures at baseline and 6-month follow-up

| Baseline | 6-month follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Score mean (s.d.) |

n | Score mean (s.d.) |

|

| GAF functioning | 61 | 44.72 (10.73) | 57 | 46.98 (12.98) |

| PSP | 147 | 63.63 (16.71) | 148 | 85.43 (121.62) |

| PANSS positive | 174 | 13.64 (4.63) | 171 | 12.37 (4.32) |

| PANSS negative | 174 | 12.42 (3.65) | 171 | 11.84 (3.78) |

| PANSS general | 110 | 27.78 (6.91) | 108 | 25.10 (7.09) |

| Calgary depression | 125 | 6.09 (4.67) | 125 | 4.48 (4.26) |

| QPR 15-item total | 173 | 47.46 (12.39) | 170 | 56.65 (11.55) |

| BHS total | 166 | 8.49 (5.96) | 122 | 8.22 (5.31) |

| SERS positive | 173 | 39.70 (13.46) | 121 | 40.35 (13.42) |

| SERS negative | 173 | 36.11 (14.64) | 121 | 34.35 (14.34) |

BHS, Beck Hopelessness Scale; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PSP, Personal and Social Performance; QPR, Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery; SERS, Self Esteem Rating Scale.

Model of recovery and negative emotion

Recovery and negative emotion were highly correlated at each time point (r = −0.66 in both). These core constructs were entered into a cross-lagged autoregressive model, as shown in Fig. 1, which for simplicity does not show these within time-point correlations. Table 3 shows the parameter estimates for this model. Both recovery and negative emotion at time 1 were significant predictors of recovery at time 2, but only negative emotion at time 1 was a significant predictor of negative emotion at time 2. The R 2 value for recovery at time 2 was 31.8% and for negative emotion at time 2 was 58.3%. The large R 2 for negative emotion at time 2 was mainly accounted for by its relationship with negative emotion at the previous time point.

Fig. 1 Path diagram of core model (model 1) showing standardised regression coefficients (bold type indicates significance at P<0.05).

Rec, recovery; Nemo, negative emotion; suffix indicates time 1 or 2.

Table 3 Parameter estimates for core model of recovery and negative emotion (n = 110)

| B | SE | P | Beta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor of recovery at time 2 | ||||

| Recovery at time 1 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.35 |

| Negative emotion at time1 | −0.85 | 0.31 | 0.006 | −0.27 |

| Predictor of negative emotion at time 2 | ||||

| Recovery at time 1 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.213 | −0.09 |

| Negative emotion at time 1 | 0.64 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.70 |

SE, standard error.

Further development and testing of the model

The influence of the test variables on negative emotion and recovery was evaluated by comparing the core model of recovery and negative emotion above with each of the test models (models 2.1–2.4) described below. The fit of these nested models was formally compared using Satorra–Bentler corrected likelihood ratio chi-squared tests. In each test model the core model was added to by including extra predictors of the outcome variables (recovery and negative emotion at time 2). In the first test model (2.1) overall PANSS symptom scores at times 1 and 2 were added as additional predictors. In model 2.3 the extra predictors were the hopelessness scores at time 1 and time 2. Positive self-esteem was the extra predictor in model 2.3 and functioning was included in model 2.4. The results of the likelihood ratio tests comparing each of models 2.1–2.4 with the core model can be found in online Table DS1. All models improved significantly on the fit of the core model, with the largest improvements seen in the prediction of recovery scores at time 2 due to hopelessness and positive self-esteem.

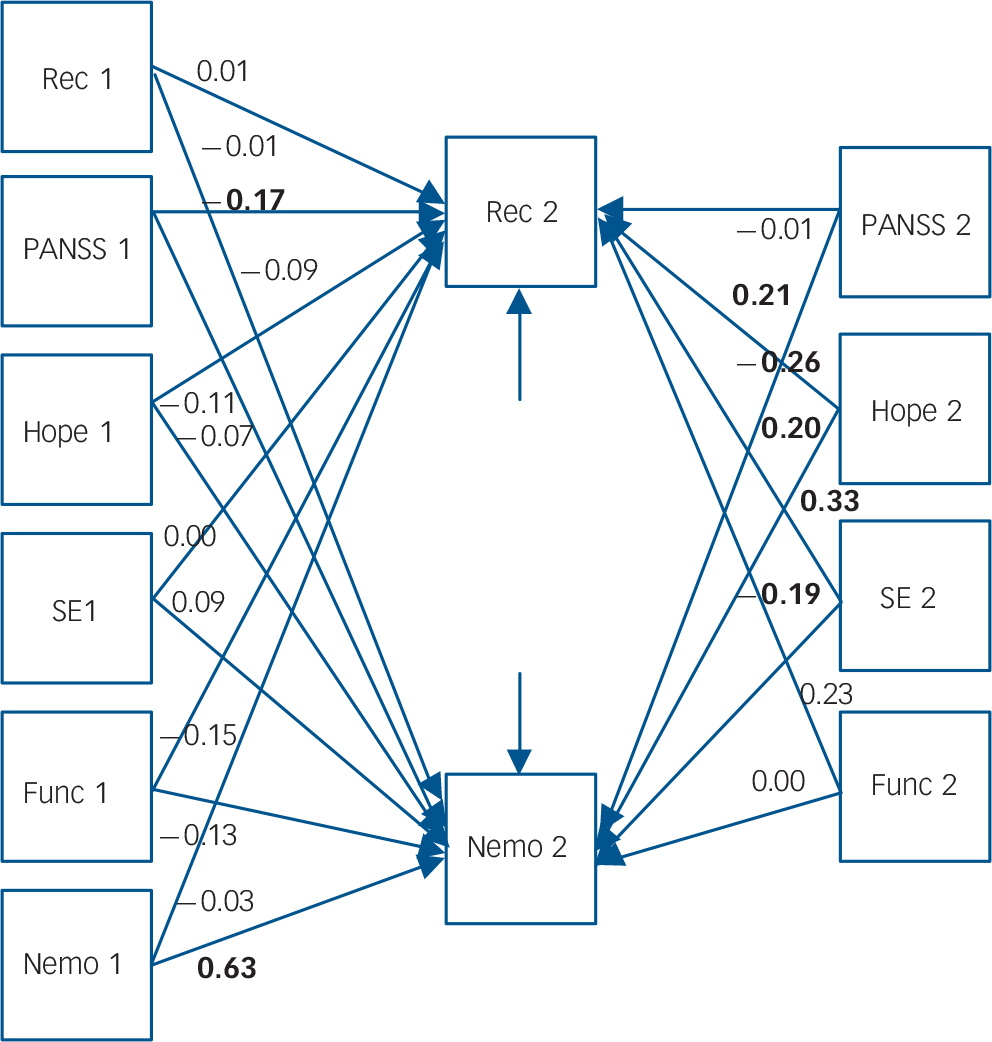

A final model was then fitted, which combined the predictors that were tested separately in models 2.1–2.4 into a single model, 2.5 (Fig. 2); the parameter estimates for this model are shown in Table 4. Recovery at time 2 was predicted by symptoms at time 1 and hopelessness and positive self-esteem at time 2. After accounting for these influences, recovery at time 1 was no longer a significant predictor of recovery at time 2. Negative emotion at time 1 was a significant predictor of negative emotion at time 2, along with symptoms, hopelessness and positive self-esteem at time 2.

Fig. 2 Path diagram of model 2.5, showing standardised regression coefficients (bold type indicates significance at P<0.05).

Func, functioning; Hope, hopelessness; Nemo, negative emotion; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; Rec, recovery; SE, self-esteem (suffix indicates time 1 or time 2).

Table 4 Parameter estimates for full model (model 2.5) (n = 110)

| B | SE | P | Beta | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor of recovery at T 2 | ||||

| Recovery T 1 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.01 |

| Negative emotion T 1 | −0.09 | 0.38 | 0.81 | −0.03 |

| PANSS score T 1 | −3.49 | 1.56 | 0.03 | −0.17 |

| Hopelessness T 1 | −0.18 | 0.13 | 0.17 | −0.11 |

| Positive self-esteem T 1 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.98 | 0.00 |

| Functioning T 1 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.1 |

| PANSS score T 2 | −0.32 | 2.38 | 0.89 | −0.01 |

| Hopelessness T 2 | −0.50 | 0.14 | 0.00 | −0.26 |

| Positive self-esteem T 2 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| Functioning T 2 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Predictor of negative emotion at T 2 | ||||

| Recovery T 1 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.93 | −0.01 |

| Negative emotion T 1 | 0.57 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.63 |

| PANSS score T 1 | −0.57 | 0.47 | 0.22 | −0.09 |

| Hopelessness T 1 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.40 | −0.07 |

| Positive self-esteem T 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.09 |

| Functioning T 1 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.68 | −0.03 |

| PANSS score T 2 | 1.46 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| Hopelessness T 2 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.20 |

| Positive self-esteem T 2 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.19 |

| Functioning T 2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.00 |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SE, standard error; T 1, time 1 (baseline); T 2, time 2 (follow-up).

Checking for endogeneity

There was a possibility that regressing closely related constructs upon one another within each data collection time point would be stretching assumptions of exogeneity with regard to these constructs. To test for this we ran an additional model, 2.6, which regressed recovery and negative emotion at time 2 on the other variables from time 1 only, not including the other time 2 variables as predictors. Symptoms and positive self-esteem at time 1 were significant predictors of recovery beliefs at time 2, each with broadly equal magnitude (online Table DS2). These predictors accounted for 44% of the variance in recovery at time 2. By far the strongest predictor of negative emotion at time 2 is the time 1 score on this variable. No other time 1 variable was a significant predictor of negative emotion at time 2 (R 2 = 61%). The fact that recovery and negative emotion have different sets of predictors is evidence in support of the fact that these are distinct constructs.

Confounding

In the previous analyses no attempt was made to control for the effects of demographic and other potentially confounding factors. Such variables available in this study were age, gender, marital status, employment status, religious beliefs and whether the participant was recruited from an early intervention or other service. We therefore fitted the same series of models above, but this time regressed the outcome variables (i.e. recovery and negative emotion at time 2) on these covariates. The pattern of model improvement was identical to that seen in Table 4, and the only significant potential confounder variable was gender. We decided to fit a final model exploiting the fact that we could plausibly assume that gender was a truly exogenous variable and so include it as a predictor of both the time 1 and time 2 outcomes. The results for this model (M3) are shown in online Table DS3. The pattern of significant results in model 3 is identical to that in model 2.6 with the notable addition that gender is a significant and substantial predictor of recovery score at time 2, with men having an average recovery score four points less than women. This is despite the fact that gender was a significant predictor neither of recovery at time 1 nor of negative emotion at either time point. It was not simply the case that one of these gender effects had reached significance and the other had not – a test of the difference between the effects of gender on recovery between time 1 and time 2 was also significant (P<0.01).

Discussion

Subjective recovery scores at time 2 were predicted by negative emotion, positive self-esteem and hopelessness, and to a lesser extent by symptoms and functioning at time 1. Additionally, current recovery score was predicted by current hopelessness and positive self-esteem. Current recovery score was not predicted by past recovery scores after accounting for past symptoms and current hopelessness and positive self-esteem. The strongest predictor of negative emotion was past negative emotion, suggesting a trait-like interpretation. Other predictors of negative emotion included current scores for symptoms, hopelessness and positive self-esteem. The analysis supports the notion that recovery and negative emotion are distinct but related constructs, each with a distinct set of predictors. Additionally, we found that gender was a significant predictor of recovery score over time, with men having lower recovery scores than women. Gender did not predict recovery scores at baseline, or negative emotion at either time point.

Comparison with previous research

Previous research has highlighted the importance of recovery as defined by the service user, which is often characterised by themes including hope, empowerment and social support. Reference Deegan4–Reference Ridgeway8 Several qualitative research studies have been conducted including a service user-led study which revealed themes of rebuilding self, rebuilding life and hope for a better future as central to the recovery process. Reference Pitt, Kilbride, Nothard, Welford and Morrison5 A recent systematic review of recovery resulted in the ‘CHIME’ conceptual framework of recovery with five core processes: connectedness, hope, identity, meaning and empowerment. Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade24 Our study is consistent with previous studies that suggest a role for hope and self-esteem in personal recovery.

The findings from our longitudinal study replicate and extend those from cross-sectional studies. For example, Morrison et al assessed 122 individuals with experience of psychosis and found that personal recovery ratings were directly influenced by negative emotion and internal locus of control. Reference Morrison, Shyrane, Beck, Heffernan, Law and McCusker9 Positive symptoms and internal locus of control appeared to have an indirect effect of recovery mediated by negative emotion, which suggests that psychosocial factors were more directly related to personal recovery judgements than neuropsychiatric factors. Similarly, these findings are consistent with those that have examined the relationship between symptom remission, functioning and psychological factors over shorter moment-to-moment time frames. For example, a study that used an experience sampling method with 177 individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia found that negative affect was significantly related to symptom remission and functioning. Reference Oorschot, Lataster, Thewissen, Lardinois, van Os and Delespaul25 These results suggest that emotion – particularly negative emotion – may mediate the relationship between psychological and neuropsychiatric variables and recovery. Our study suggests a key role for negative emotion in predicting subjective recovery scores over more extended periods. Moreover, it supports previous research that suggests a key role for emotion in psychosis, Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington26–Reference Freeman and Garety28 and extends these findings in terms of their relevance for subjective recovery. The cognitive model of psychosis suggests that emotional changes occur within the context of psychotic experiences. Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington26 These emotional changes can feed into the way psychotic experiences are processed and appraised, maintaining their occurrence. Reference Garety, Kuipers, Fowler, Freeman and Bebbington26 Further research has supported this claim that low mood, low self-esteem and anxiety contribute to the development and maintenance of psychosis. Reference Smith, Fowler, Freeman, Bebbington, Bashforth and Garety27,Reference Barrowclough, Tarrier, Humphreys, Ward, Gregg and Andrews29–Reference Hartley, Barrowclough and Haddock31 Our findings suggest that emotion may mediate the relationship between experiences of psychosis and subjective recovery judgements. Negative emotion could contribute to the maintenance of psychosis, which will in turn affect the individual's quality of life, social functioning, hope and self-esteem, resulting in lower subjective recovery beliefs. Lower subjective recovery scores and recovery beliefs could be an additional perpetuating factor in psychosis.

Previous research suggests a role of gender in outcomes for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, finding that men generally have lower recovery expectations than women. Reference Goldstein, Tsuang and Faraone32 We found this to be the case at time 2 but not time 1. This finding is intriguing because it suggests that different processes may be at work shaping the development of recovery beliefs of men and women over time. Gender was not a predictor of negative emotion at either time point, suggesting that the relationship between recovery and gender was not mediated by negative emotion. It is possible that other processes may explain these differences; for example, sample selection might have played a part if men and women find their way into mental health services at different rates and at different stages of recovery. In addition, this research only explored demographic categories of male and female. Further research using a more sociocultural approach to examine gender roles and identity, reviewed by Nassar et al, Reference Nassar, Walders and Jankins33 in relation to recovery from psychosis may improve our understanding of the role of gender in both negative emotion and recovery.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The main strength of our study is its longitudinal design, allowing exploration of factors that may predict recovery. However, there are a number of methodological limitations. First, the study used a relatively modest sample size which was recruited by convenience sampling. Further research could study a larger sample, allowing for more extensive testing with more potential predictors and parameters. Second, the sample comprised mostly men and was diagnostically heterogeneous, which might mean that conceptualisations of recovery were very different within the sample. Similarly, information on length of illness was not collected for this data-set and this may have been an additional predictor of subjective recovery scores. However, the sample was recruited across a variety of services and settings to ensure it was representative of the target clinical population. Rates of attrition were low, with only three people not completing the 6-month follow-up assessment. However, only 110 participants completed all measures at both time points and were included in the final analysis. Additionally, because of the nature of the data used for this study (taken from a large research programme), it was not possible to describe fully the recruitment process in terms of numbers of participants approached at each stage for each study. Finally, although this study is one of the few to assess both neuropsychiatric and psychosocial factors that may predict recovery over time, the follow-up period was relatively short (6 months). Further research could examine the course of recovery and associated predictors over a longer time frame.

Future research examining the impact of insight on recovery judgements and on negative emotion would be beneficial. Previous research has suggested mixed results with regard to insight and recovery. For example, in one study improved insight was associated with improved outcomes, Reference Rosen and Garety34 whereas other studies have suggested that increased insight can be associated with increased negative outcomes including greater suicidality. Reference Kim, Jayathilake and Meltzer35 Developing an understanding of the role of insight in relation to recovery and negative emotion would be beneficial.

Implications for clinical practice

There are several potential implications of this research. Interventions that aim to reduce negative emotion while promoting self-esteem and hope may be beneficial to promoting recovery. Strategies such as improvement of self-esteem, Reference Hall and Tarrier36 and reduction of internalised stigma, Reference Lucksted, Drapalski, Calmes, Forbes, DeForge and Boyd37 for example, may lead to improved recovery outcomes. Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) has been recommended in recent guidelines for the treatment and management of psychosis. 1 An editorial on the future of CBT highlighted the need for the approach to evolve in light of our advancing understanding of the role of emotion in psychosis. Reference Birchwood and Trower38 Our study supports this viewpoint, suggesting a key role for negative emotion in recovery outcomes, which should be addressed in future therapeutic intervention trials.

Interventions that aim to reduce the distress associated with experiences of psychosis and improve emotional processing may also be of benefit. A recent study piloted a brief intervention to reduce distress associated with persecutory delusions. Reference Foster, Startup, Potts and Freeman39,Reference Hepworth, Startup and Freeman40 The intervention emotional processing and metacognitive awareness (EPMA) was effective in reducing distress associated with delusions by enhancing the emotional processing of experiences. Reference Hepworth, Startup and Freeman40 It was suggested that worry might lead to distress by preventing emotional processing of upsetting experiences such as delusions. Consideration of other factors that might reduce distress surrounding experiences of psychosis should also be considered. For example, a current trial is investigating the impact of sleep on psychosis using a cognitive–behavioural intervention for insomnia. Reference Freeman, Startup, Myers, Harvey, Geddes and Yu41 Early pilot studies of this approach have indicated improvements in sleep, as well as reduction in delusions, anomalies of experience, anxiety and depression. Reference Myers, Startup and Freeman42 Emphasis in services should expand from purely symptom- and functioning-based approaches towards a more psychosocial approach, taking into account the key role of negative emotion on personal recovery outcomes.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.