Reports in the psychiatric literature that comorbid personality disorder is associated with a poor outcome in depression have recently been challenged (Reference Brieger, Ehrt and BloeinkBrieger et al, 2002; Reference MulderMulder, 2002). This is an important clinical issue that needs to be resolved and we judged that there have now been sufficient high-quality studies to enable a definitive answer to be obtained from a systematic review. Before the introduction of DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1980) there were few studies examining the influence of personality disorder on the outcome of depression, although clinical opinion suggested that people with personality disorder responded less well to treatment (Reference SargantSargant, 1966) and follow-up studies supported this (Reference Greer and CawleyGreer & Cawley, 1966). However, both before and since the introduction of DSM-III, personality problems have been studied in some depth using self-rating questionnaires in which personality abnormality is assessed dimensionally (Reference EysenckEysenck, 1959; Reference Eysenck and EysenckEysenck & Eysenck, 1964; Reference CloningerCloninger, 1987). Although there is good evidence that personality abnormality is best viewed as a dimensional construct (Reference LivesleyLivesley, 1991), in clinical practice decisions are dichotomous and are aided by a categorical diagnostic system; hence we used this in our systematic review.

METHOD

The aim of the meta-analysis was to examine all studies of outcome in depressive disorders in which: (a) personality disorder was assessed formally and (b) outcome was recorded either using standard rating scales, such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1960) or another measure, such as clinical judgement.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were broad to ensure maximum accrual of information for systematic review. Papers were selected if: (a) written in English; (b) participants were assessed for both depression and personality disorder using a scale published in a peer-reviewed journal; (c) the population studied was aged at least 18 years; (d) assessment of outcome of depression was at least 3 weeks after initial assessment, this being considered the minimum time necessary for treatment response. Both observational studies and randomised trials were included and there were no restrictions with regard to type of treatment or its duration.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that examined personality using a dimensional scale were excluded, as these could not be compared directly with those in which a categorical diagnosis of personality disorder was made.

Search method

Medline, Clinhal and Psychinfo were searched online from 1966, 1982 and 1882, respectively. The terms DEPRESSION, MENTAL ILLNESS and PERSONALITY DISORDER were entered and combined. All abstracts were reviewed and those with data suggesting satisfaction of the inclusion criteria read in full.

In addition, a hand search of the Journal of Affective Disorders was carried out by G.N.-H. This served as an audit of the online search and provided additional sources of information. All relevant review articles were also examined closely for eligible studies, especially those by McGlashan (Reference McGlashan1987), Reich & Green (Reference Reich and Green1991), Reich & Vasile (Reference Reich and Vasile1993), Shea et al (Reference Shea, Widiger and Klein1992), Ilardi & Craighead (Reference Ilardi and Craighead1995), Corruble et al (Reference Corruble, Ginester and Guelfi1996), Dreessen & Arntz (Reference Dreessen and Arntz1998) and Mulder (Reference Mulder2002). The ‘grey’ literature was not examined as it was considered unlikely to provide further data.

Data extraction and checking

Two-by-two tables of the numbers of patients with or without personality disorder cross-classified by response to treatment (and stratified by treatment modality when possible) were drawn up for each paper, either by direct extraction from published tables and text (including associated papers), derived from summary percentages, or reconstructed from summary statistics such as χ2. The resultant 2 × 2 tables were cross-checked against all information within each published paper (counts, percentages, summary statistics, test statistics) to check for and resolve (multiple) inconsistencies. For papers that did not report a dichotomous outcome but presented outcome as a mean and standard deviation (s.d.) on a rating scale such as the HRSD, the number of patients who responded was defined as the percentage with outcome score < 6 and estimated using the methods of Whitehead et al (Reference Whitehead, Bailey and Elbourne1999), assuming a normal distribution of scores at outcome and allowing different variances in those with and without personality disorders. In papers that reported means alone, standard deviations were estimated by interpolation, from a regression of ln(s.d.) on ln(mean) in the six studies that reported these for the HRSD. Only the earliest outcome was allowed for each study; continuous outcomes were used only when no dichotomous outcome was reported.

For some recent papers where the required data on personality status (or depression) seemed to be implied but could not be extracted or derived, authors were contacted with a request for relevant information in the form of a 2 × 2 table.

Every paper included in the meta-analysis was read and the data were extracted and cross-checked independently by two authors (G.N.-H. and T.J.); discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

Log (odds ratios, ORs) and their standard errors from each study were entered into the RevMan 4.2. meta-analysis program (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK; see http://www.cc-ims.net/RevMan/current.htm) using the generic inverse variance option. Results have been summarised using conventional Forest plots and ORs, stratified by features of the studies included. Summary ORs were estimated using a random effects model.

RESULTS

The search

Online search found 890 potentially relevant papers. Abstracts from all of these were reviewed for useful data and 759 were rejected as obviously unsuitable (e.g. rodent studies). The remaining 131 were read in full and 99 were rejected for a variety of reasons, including (a) no usable data; (b) no categorical diagnosis of personality disorder; and (c) no recognised instrument used for diagnosis. The remaining 32 studies were included in the review. Hand search of the Journal of Affective Disorders and cross-checking of papers cited by review articles revealed no extra papers, indicating that our search strategy was reasonably comprehensive. Review of the literature in August 2004 highlighted two papers published since the initial review in February 2002, which have been included (Reference Kool, Dekker and DuijsensKool et al, 2003; Reference Casey, Birbeck and McDonaghCasey et al, 2004).

Included studies

Characteristics of the 34 studies available for meta-analysis are summarised in Table 1 in chronological order of publication. There were 17 (50%) studies from North America, 15 (44%) from Europe and 2 (6%) from the Far East. Four studies were located in Iowa, USA (Pfohl et al, Reference Pfohl, Stangl and Zimmerman1984, Reference Pfohl, Coryell and Zimmerman1987; Zimmermann et al, 1986; Reference Black, Bell and HulbertBlack et al, 1988), and have been selectively included in the meta-analysis since the first three clearly report different aspects of the same study. Four studies located in Pittsburgh, USA (Reference Pilkonis and FrankPilkonis & Frank, 1988; Reference Shea, Pilkonis and BeckhamShea et al, 1990; Reference Stuart, Simons and ThaseStuart et al, 1992; Reference Hirschfeld, Russell and DelgadoHirschfeld et al, 1998) have all been included since they report independent data-sets (P. Pilkonis, personal communication, 2004). For the Nottingham study of neurotic disorders (Reference Tyrer, Seivewright and FergusonTyrer et al, 1990), only data for patients with dysthymia have been abstracted, and from the study of Leibbrand et al (Reference Leibbrand, Hiller and Fichter1999), only data for patients with comorbid major depressive disorder.

Table 1 Characteristics of studies reporting association between personality disorder and outcome in depression

| First author (year) | Study | Criteria | Response | Treatment | Time (weeks) 7 | Personality disorder | No personality disorder | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Type 1 | IP/OP | Depression | Personality disorder | Good 8 | Poor 9 | Good 8 | Poor 9 | |||||||||

| Charney (1981) | USA | CNR | IP | DSM-III | DSM-III | Good or complete | Drugs, PSY | 12 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 2 | |||||

| Tyrer (1983) | England | RCT | Both | HRSD | PAS | ≥50%↓HRSD, HRSA | Drugs | 4 | 3 | 29 | 13 | 15 | |||||

| Pfohl (1984, 1987) | USA | PCS | IP | DSM-III | DSM-III | ≥50%↓HRSD | ECT, drugs, neither | 4 (mean) | 10 | 31 | 22 | 15 | |||||

| Davidson (1985) | USA | RCT | IP | RDC | DSM-III | HRSD 2 | Drugs | 4 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Shawcross (1985) | England | PCS | OP | ICD-9 | PAS | Clinical judgement | Drugs | 60 (mean) | 5 | 12 | 28 | 5 | |||||

| Sauer (1986) | Germany | PCS | IP | DSM-III | DSM-III | ≥50%↓HRSD | Drugs | 3 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Black (1988) | USA | CNR | IP | DSM-III | DSM-III | Recovered - case notes | Drugs, ECT, other | NK | 32 | 44 | 91 | 61 | |||||

| Goethe (1988) | USA | CNR | IP | DSM-III | DSM-III (?) | Clinical judgement | Drugs, ECT | 20 (mean) | 40 | 84 | 40 | 37 | |||||

| Pilkonis (1988) | USA | PCS | OP | RDC | DSM-III | Complex 3 | Drugs, PSY | 16+ | 17 | 32 | 34 | 19 | |||||

| Thompson (1988) | USA | RCT | OP | RDC | DSM-III | No MDD | PSY | 24 | 13 | 12 | 40 | 10 | |||||

| Andreoli (1989) | Switzerland | PCS | IP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | Symptomatic recovery | Drugs+IP | NK | 11 | 16 | 6 | 14 | |||||

| Joffe (1989) | Canada | PCS | OP | DSM-III, RDC | DSM-III | HRSD < 5 | Drugs | 5 | 16 | 17 | 7 | 2 | |||||

| Keitner (1989) | USA | PCS | IP | DSM-III | DSM-III (?) | HRSD < 7 for 3 months | Drugs, PSY | 26 | 2 | 6 | 27 | 43 | |||||

| Reich (Reference Reich1990) | USA | PCS | OP | RDC | PDQ, GAS | Not taking drugs | Drugs | 26 | 14 | 11 | 6 | 4 | |||||

| Shea (1990) | USA | RCT | OP | RDC | DSM-III | HRSD ≤ 6 | Drugs, PSY | 16 | 54 | 124 | 30 | 31 | |||||

| Tyrer (1990) | England | RCT | OP | DSM-III | PAS | MADRS < 6 | Drugs, PSY | 10 | 5 | 26 | 10 | 20 | |||||

| Ansseau (1991) | Belgium | PCS | OP | DSM-III | DSM-III | Completing study | Drugs | 8 | 19 | 3 | 17 | 7 | |||||

| Stuart (1992) | USA | PCS | OP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | HRSD < 7 for ≥ 4 weeks | PSY | 16 | 7 | 7 | 23 | 16 | |||||

| Diguer (1993) | USA | PCS | OP | DSM-III-R, RDC | DSM-III-R | BDI 2 | PSY | ∼ 16 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Sato (1993) | Japan | PCS | OP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | Complex 4 | Drugs | 17 | 27 | 25 | 32 | 12 | |||||

| Fava (1994) | USA | RCT | OP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | HRSD 2 | Drugs | 8 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Sullivan (1994) | New Zealand | RCT | OP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | HRSD < 8 | Drugs | 6 | 28 | 25 | 22 | 24 | |||||

| Hardy (1995) | England | RCT | OP | DSM-III | DSM-III-R | BDI < 7 (?) | PSY | NK | 13 | 14 | 53 | 32 | |||||

| Patience (1995) | Scotland | RCT | OP | DSM-III | PAS | HRSD ≤ 6 | Drugs, PSY | 16 | 18 | 20 | 42 | 21 | |||||

| Casey (1996) | Ireland | PCS | IP | DSM-III-R | PAS | Readmission | ECT | 52 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 9 | |||||

| Ilardi (1997) | USA | PCS | IP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | Depressive relapse | Drugs, ECT | 26 | 5 | 17 | 24 | 4 | |||||

| Ekselius (1998) | Sweden | RCT | OP | DSM-III-R | SCID | Complex 5 | Drugs | 24 | 171 | 18 | 110 | 9 | |||||

| Hirschfeld (1998) | USA | RCT | OP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | Complex 6 | Drugs | 12 | 153 | 153 | 171 | 146 | |||||

| Ezquiaga (1998) | Spain | PCS | OP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | HRSD < 8 | Drugs, PSY | 26 | 4 | 21 | 37 | 25 | |||||

| Leibbrand (1999) | Germany | PCS | IP | DSM-IV | DSM-IV | BDI 2 | PSY | 10 (mean) | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Fava (2002) | USA | RCT | OP | DSM-III-R | SCID-P | HRSD 2 | Drugs | 8 | - | - | - | - | |||||

| Viinamaki (2002) | Finland | PCS | OP | DSM-III-R | SCID-II-P | BDI < 10 | Drugs, PSY | 26 | 8 | 44 | 35 | 30 | |||||

| Kool (2003) 10 | Netherlands | RCT | OP | DSM-III-R | DSM-III-R | HRSD < 8 | Drugs, PSY | 24 | 30 | 55 | 14 | 29 | |||||

| Casey (2004) 10 | Europe | RCT | OP | ICD-10, DSM-IV | PAS | BDI < 7 | PSY | 26 | 11 | 43 | 85 | 164 | |||||

↓, reduction; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CNR, case note review; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; GAS, Global Assessment Scale; HRSA, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IP, in-patient; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; NK, not known; OP, out-patient; PAS, Personality Assessment Schedule; PCS, prospective case series; PDQ, Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire; PSY, psychological therapy; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RDC, Research Diagnostic Criteria; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders.

1. Prospective case series include non-randomised trials.

2. Continuous outcome only reported (no dichotomy).

3. Using own algorithm.

4. 17-item HRSD < 6 and full recovery of social functioning 16 weeks after starting treatment and no sign of recurrence of depression during 4 weeks after first two criteria met.

5. ≥ 50% reduction in MADRS score at 24 weeks, Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale score 1-3 and CGI Improvement (CGI-I) scale rated at least ‘much improved’.

6. CGI-I score of 1 or 2 and HRSD > 9, or ≥ 50% reduction in HRSD score with HRSD < 15 and CGI severity 3.

7. Time interval from start to outcome evaluation.

8. Meets response criteria.

9. Does not meet response criteria.

10. Study added to the original data-set after a further literature review in August 2004.

Out of the 34 studies, 17 (50%) were prospective case series (cohort studies), 14 (41%) were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 3 (9%) were case series reviews; the majority (22 out of 34, 65%) focused on out-patients. The interval from the start of treatment to assessment of outcome varied from 3 weeks to just over a year (median=16 weeks, interquartile range 8-24); this parameter was not given in 3 studies. Response was based on rating scales for depression in 24 (71%), objective criteria for relapse in 1 (3%) and less objective criteria in 9 (26%). Out of the 24 studies using common depression scales as outcomes (HRSD, Beck Depression Inventory or Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale), 5 (21%) reported only means (with or without s.d.), 3 (13%) reported percentages achieving at least 50% reduction from baseline, 12 (50%) reported percentages below a declared cut-off point and 4 (17%) used a complex combination. Table 1 also shows the numbers of patients with and without personality disorder with good or poor outcome, except for 6 studies that did not report a dichotomised response; overall 45% (746 out of 1663) of those with personality disorder had a ‘good’ outcome compared with 57% (1054 out of 1860) of those without.

Table 2 summarises the results from studies reporting mean outcome scores on the HRSD, BDI and MADRS, together with estimates of ORs obtained from means (and s.d.) using the methods of Whitehead et al (Reference Whitehead, Bailey and Elbourne1999). Also shown for comparison are ORs obtained from dichotomised outcomes reported by individual studies. Given the width of the 95% CI around the ORs, it is difficult to detect divergence between the two sets. However, it should be noted that the point estimates of the ORs estimated from means (and s.d.) are reasonably close to those reported for dichotomised outcomes, with the exception of Zimmerman et al (Reference Zimmerman, Coryell and Pfohl1986) (which occurs only when treatment is stratified by modality), Casey et al (Reference Casey, Meagher and Butler1996) and Viinamaki et al (Reference Viinamaki, Hintikka and Honkalampi2002). On this basis we consider that the methods of Whitehead et al are sufficiently robust to allow inclusion of the six studies in Table 2 that do not report a dichotomised outcome. For the other ten studies in Table 2, the dichotomised outcome is used in the meta-analysis.

Table 2 Odds ratios estimated from continuous scales and reported from dichotomous outcomes 1

| First author (year) | Scale | Score: mean (s.d., n) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality disorder | No personality disorder | Normal | Dichotomy | ||||||||

| Baseline | End | Baseline | End | ||||||||

| Zimmerman (1986) | HRSD | 24.2 (4.9, 10) | 10.2 (6.9, 10) | 21.0 (5.6, 15) | 8.5 (7.7, 15) | 1.7 (0.4-7.3) | 4.6 (0.7-29) | ||||

| Shea (1990) | HRSD | 20.6 (4.5, 187) | 11.3 (7.5, 178) | 20.4 (4.8, 62) | 9.6 (7.5, 61) | 1.5 (0.8-2.5) | 2.2 (1.2-4.0) | ||||

| Tyrer (1990) | MADRS | 22.4 (7.9, 31) | 14.6 (8.0, 31) | 21.8 (7.0, 30) | 13.4 (10.5, 30) | 2.0 (0.7-5.7) | 2.1 (1.0-4.1) | ||||

| Sullivan (1994) | HRSD | 21.9 (4.5, 46) | 8.3 (6.0, 46) | 21.7 (4.7, 39) | 8.4 (6.4, 39) | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 0.8 (0.3-1.8) | ||||

| Patience (1995) | HRSD | 19.6 (6.3, 38) | 9.2 (−, 38) | 16.7 (5.5, 63) | 5.6 (−, 63) | 2.5 (1.2-4.9) | 2.2 (0.9-5.1) | ||||

| Hardy (1995) | BDI | 25.0 (7.5, 27) | 13.5 (8.6, 27) | 20.3 (6.3, 87) | 8.2 (7.0, 85) | 2.6 (1.1-6.0) | 1.8 (0.7-4.3) | ||||

| Casey (1996) | HRSD | 31.1 (−, 18) | 16.7 (−, 18) | 28.4 (−, 22) | 9.0 (−, 22) | 5.7 (1.2-26) | 1.2 (0.3-41) | ||||

| Ekselius (1998) | MADRS | 29.0 (5.2, 189) | 5.2 (5.8, 189) | 27.2 (4.7, 119) | 4.8 (6.8, 119) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.2 (0.7-1.9) | ||||

| Viinamaki (2002) | HRSD | 20.0 (6.7, 52) | 13.9 (6.4, 52) | 18.0 (6.3, 65) | 10.0 (6.8, 65) | 3.2 (1.4-7.2) | 6.4 (2.6-16) | ||||

| Kool (2003) | HRSD | 20.4 (4.7, 85) | 12.7 (7.9, 85) | 20.4 (5.2, 43) | 11.6 (7.8, 43) | 1.3 (0.6-2.6) | 1.1 (−) | ||||

| Davidson (1985) | HRSD | - | 12.4 (6.1, 15) | - | 12.7 (9.1, 20) | 1.7 (0.4-7.3) | - | ||||

| Sauer (1986) | HRSD | - | 23.8 (−, 13) | - | 16.8 (−, 37) | 5.3 (0.3-81) | - | ||||

| Diguer (1993) | BDI | 29.1 (7.2, 12) | 19.2 (9.9, 12) | 26.8 (6.8, 13) | 8.8 (6.2, 13) | 4.7 (0.7-28) | - | ||||

| Fava (1994) | HRSD | - | 8.2 (−, 62) | - | 5.7 (−, 21) | 1.9 (0.8-4.2) | - | ||||

| Leibbrand (1999) | BDI | 25.1 (10.8, 39) | 13.3 (11.6, 39) | 22.5 (10.8, 18) | 12.7 (9.1, 18) | 0.8 (0.3-2.4) | - | ||||

| Fava (2002) | HRSD | - | 10.8 (−, 243) | - | 9.9 (−, 135) | - | - | ||||

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

1. Odds ratios (and 95% CI) were estimated from continuous data using the methods of Whitehead et al (Reference Whitehead, Bailey and Elbourne1999), assuming a normal distribution of scores at outcome (with different variances in the with and without personality disorder groups) and a cut-off point of 6.0. Also shown are odds ratios estimated from dichotomous data as reported in the same papers though not necessarily with the same definition of response. For five studies (Reference Sauer, Kick and MinneSauer et al, 1986; Reference Fava, Bouffides and PavaFava et al, 1994; Reference Patience, McGuire and ScottPatience et al, 1995; Reference Casey, Meagher and ButlerCasey et al, 1996; Reference Fava, Farabaugh and SickingerFava et al, 2002) that report only means at outcome (or percentage change from baseline), the standard deviations (s.d.) have been estimated by interpolation from a linear regression of In(s.d.) on In(mean) for the remaining six studies (12 points) that used the HRSD.

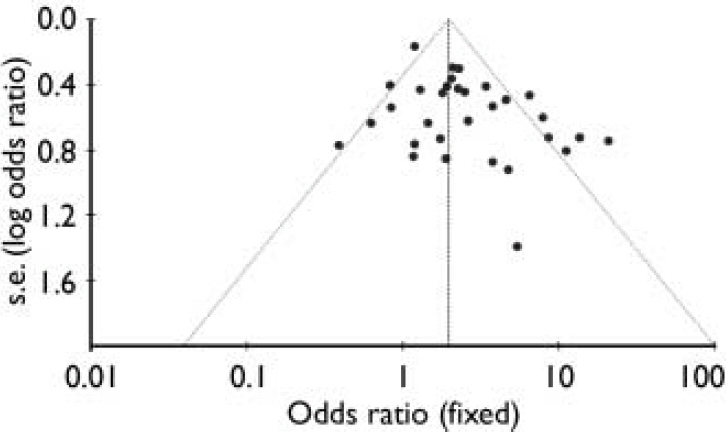

Figure 1 shows a funnel plot of ORs (under a fixed-effects model) from the 34 studies in Table 1. In the absence of publication bias the points should be symmetrical about the vertical line at the pooled ORs. Although reasonably symmetrical, it does suggest the possible absence of small studies (large standard errors) with negative associations (ORs around 1 or less), which may be a natural consequence of the general tendency to publish ‘positive’ studies.

Fig. 1. Funnel plot of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 2 is a forest plot of ORs from the 34 studies, stratified by type of outcome measure and ordered by date of publication. Within the two largest groups, Hamilton-type criteria and miscellaneous criteria, there is heterogeneity and in view of this, the meta-analysis employs a random-effects model. Despite this heterogeneity, the ORs from the studies that employed Hamilton-type criteria show a degree of consistency that is perhaps remarkable given the diverse methodologies of the studies included. All except two of the point estimates of the ORs lie to the right of the (null effect) vertical line, 10 out of the 18 fail to demonstrate statistical significance at P=0.05, and the remaining 8 achieve significance with ORs in excess of 1. Overall the odds of response to treatment for depression are roughly doubled in the absence of a personality disorder. This estimate is also consistent with the overview from all 34 studies.

Fig. 2 Random-effects meta-analysis stratified by outcome type and ordered by year of publication (only first authors are shown).

Figure 2 also shows, as expected, that the results from the studies that used miscellaneous criteria for response are more diverse than those that used Hamilton-type criteria, but none the less provide a consistent overview. There are fewer studies, six in total, that report continuous outcomes only, and only one of these excludes association with ORs greater than 2. There is no evidence of a trend with year of publication within any of the strata.

A secondary analysis was carried out by subdividing studies into four predominant treatment modalities: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), drug treatment alone, any form of psychotherapy alone, and both drugs and psychotherapy available, although not necessarily used in combination. The purpose of this was to explore whether any particular modality was suggestive of better outcome, irrespective of the outcome measure employed. Figure 3 shows that all treatment modalities except ECT had a poorer outcome for the treatment of depression if personality disorder was present. The greatest divergence between the groups was among those treated with a combination of psychotherapy and drugs, those without a personality disorder being more likely to respond (OR=2.66, 95% CI 1.31-5.42) than those with a personality disorder. We caution against overinterpretation of this against a background of varying treatments, treatment intensities and durations.

Fig. 3 Random-effects meta-analysis stratified by treatment modality. ECT, electroconvulsive therapy. For each study, only the first author is shown.

In Fig. 4 the studies are stratified by their design and ordered within design type by interval from baseline to outcome assessment. The RCTs are less heterogeneous than the cohort studies and also suggest a smaller effect of personality disorder (OR=1.60 v. 2.73). Interval from baseline to outcome assessment does not appear to be related to the outcome of treatment. Table 2 shows that those with personality disorder had slightly higher mean Hamilton scores at baseline than those without (21.1 v. 19.9), and this could be associated with poorer response. However, they also had a smaller mean change (9.5 v. 11.0) and the duration of five of the seven studies exceeded 15 weeks.

Fig. 4 Random-effects meta-analysis stratified by type of study and ordered by interval to assessment (shorter time periods shown first). For each study, only the first author is shown.

DISCUSSION

In the spirit of evidence synthesis, we have described fully our search strategy, study selection, data summary and analysis to allow replication or sensitivity analysis of any aspect of our approach. We have included every study that to our knowledge satisfies our inclusion criteria and employed techniques of estimation that allow integration of diverse outcome measures. The results are clear: the co-occurrence of a personality disorder in a person with depression is about twice as likely to be associated with a poor response as in an individual without a personality disorder. This is a robust finding which is not altered significantly by the nature of the instrument used to measure depression outcome. Furthermore, no treatment modality stands out as being more effective than any other in the treatment of a person with depression and personality disorder. The trend was for psychotherapy to be associated with poorer outcome in those with personality disorder.

Overall, about 55% of patients with personality disorder had a poor outcome compared with about 45% of those without, demonstrating that many of those with depression and personality disorder remain unwell, a feature that is particularly noticeable in the long term (Reference Kennedy, Abbott and PaykelKennedy et al, 2004; Reference Tyrer, Seivewright and JohnsonTyrer et al, 2004). The total number of patients necessary to detect this difference (or larger) with 90% power, using a (two-sided) statistical test of the difference between two proportions at the 5% level of significance, exceeds 1000. None of the individual studies approached this target. The largest, by Hirschfield et al (1998), which included over 600 patients, achieved only 70% power to detect this effect. This partly explains the confusion in the literature and reinforces the need to combine evidence from separate studies to reach a sound conclusion.

Methodological strengths and weaknesses

Our research strategy was comprehensive and studies excluded because they did not satisfy our inclusion criteria did not show important differences from the included papers. Resources to include searches for papers not written in English were unavailable.

A surprising finding was the relative dearth of studies exploring this issue either as a primary or secondary research aim. Depression is extremely common, the bread and butter of day-to-day psychiatry, and this is reflected in the research. Comorbidity with personality disorder is also common, but this is not as well reflected. Only a quarter of the studies identified as potentially useful provided the necessary data and only 14 were RCTs.

Our findings do not indicate whether the influence of personality disorder is independent of intervention. They suggest, however, that the treatment of depression with psychotherapy may be less effective in those with personality disorder. A recent study using interpersonal psychotherapy as maintenance treatment for women with depression found higher rates of recurrence and more rapid relapse in a subgroup with personality disorder (Reference Cyranowski, Frank and WinterCyranowski et al, 2004). It also found an increased need for pharmacotherapy, broadly supporting this conclusion. This somewhat counterintuitive finding needs cautious interpretation as the total numbers are not large and no effort has been made to substratify psychological treatment modalities. A specific type of psychological approach might have merit in this group, as has been shown for the specific treatment of borderline personality disorder (Reference Linehan, Armstrong and SuarezLinehan et al, 1991; Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman & Fonagy, 1999; Reference Verheul, van den Bosch and KoeterVerheul et al, 2003). The better result with drug treatment may also be a direct effect of treatment on personality pathology, as has been suggested in recent studies (Reference Ekselius and von KnorringEkselius & von Knorring, 1998; Reference Fava, Farabaugh and SickingerFava et al, 2002). There also might be important variation between the effects of different antidepressants in the presence of personality disorder (Reference Mulder, Joyce and LutyMulder et al, 2003). The merits of combined drug and psychological treatment are also not yet known in the presence of personality disorder (Reference Kool, Dekker and DuijsensKool et al, 2003; Reference De Jonghe, Hendriksen and van Alstde Jonghe et al, 2004).

Similarly the absence of a clear association with response to ECT requires cautious interpretation because of the comparatively small total numbers involved. Nevertheless there is some indication that ECT may be of benefit in those with severe depression and personality disorder. In many studies, initial depression scores were higher in the groups with personality disorder, potentially leading to a spurious conclusion of poor outcome when taking a fixed-scale score for recovery status. However, the difference was not large (an HRSD score difference of less than 1.5 between groups). The group with personality disorder also showed a smaller mean change with treatment regardless of the baseline measure, and there was no apparent relationship between the OR and the duration of study.

Finally by only analysing studies in which a categorical diagnosis was used, we excluded papers that provided dimensional ratings of personality only. This, however, allows for reproducible collation of the data in a fashion that is not only amenable to analysis but useful in day-to-day practice.

Implications for clinical practice

We conclude that if comorbid personality disorder is not treated patients will respond less well to treatment for depression than do those with no personality disorder; the same may apply even if no treatment is given. There is no particular treatment that defies this association, although there is some suggestion that the negative effect of personality disorder might be attenuated by drug treatment. The results emphasise the importance of studying the simultaneous treatment of depression and comorbid personality disorder, since there is now better evidence that both drug and psychological treatments, when specifically targeted at personality pathology, might be of value (Reference Leichsenring and LeibingLeichsenring & Leibing, 2003; Reference Newton-Howes and TyrerNewton-Howes & Tyrer, 2003; Reference Tyrer, Sensky and MitchardTyrer et al, 2003). Some of the contrary findings in the literature (Reference MulderMulder, 2002) might reflect the extent to which personality disorder has been treated, either explicitly or covertly. Whatever the interpretation, a diagnosis of personality disorder is not necessarily a poor prognostic indicator. These patients simply require treatment of both the personality disorder and the depression. This offers a challenge to clinicians. Despite our best endeavours patients with personality disorder remain one of the most difficult groups in psychiatric practice.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ As co-occurrence of personality disorder with depression increases the likelihood of a poor outcome, attention should be paid to concurrent treatment of comorbid personality disorder in patients with depression.

-

▪ The treatment of comorbid personality disorder by psychological means is not supported by the meta-analysis.

-

▪ Assessment of personality status early in the treatment of depression may help to predict outcome.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Only papers using a categorical approach to personality disorder were included in the meta-analysis.

-

▪ People with a personality disorder generally had higher scores on depression rating scales at the beginning of treatment.

-

▪ It was not possible to conclude that personality disorder in itself caused the poorer outcome in depression.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.