Borderline personality disorder is characterised by a pervasive pattern of instability in affect regulation, impulse control, interpersonal relationships and self-image. Clinical hallmarks include emotional dysregulation, impulsive aggression, repeated self-injury and chronic suicidal tendencies. Reference Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan and Bohus1 The disorder leads to substantial suffering and functional impairment in those affected, Reference Skodol, Gunderson, McGlashan, Dyck, Stout and Bender2 and has a serious impact on mental health services, incurring high costs. Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen and Silk3 In a new US study the lifetime prevalence has been estimated to be about 5.9%. Reference Grant, Chou, Goldstein, Huang, Stinson and Saha4 The point prevalence rates are estimated to be about 0.7% in European national community samples. Reference Coid, Yang, Tyrer, Roberts and Ullrich5,Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and Cramer6 However, considerably higher point prevalence rates are found among primary care attenders (4.3%). Reference Moran, Jenkins, Tylee, Blizard and Mann7 The disorder often co-occurs with mood, anxiety and substance use disorders, and is also associated with other personality disorders. Reference Grant, Chou, Goldstein, Huang, Stinson and Saha4 Suicidal behaviour is reported to occur in up to 84% of patients with borderline personality disorder. Reference Soloff, Lynch and Kelly8 Comorbid mood disorders or substance use are considered the most relevant risk factors for suicide completion. Reference Black, Blum, Pfohl and Hale9 In medical settings, people with borderline personality disorder often present to emergency departments after self-harming incidents or in suicidal crises, and are often repeatedly hospitalised. Additionally, in the USA more than 80% of patients with the disorder are in individual psychotherapy for at least half of a 6-year period, and the same proportion are taking regular medication. Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen and Silk3 Treatment settings and provisions for patients may vary between different countries; nevertheless, pharmacological interventions are increasingly commonly used to treat different facets of the pathology spectrum, such as affective instability, impulsivity, dissociative states or cognitive–perceptual symptoms. 10 Associated disorders such as depression can likewise be the target of psychopharmacological interventions. Different classes of agents, such as mood stabilisers, antipsychotics and antidepressants, have been used in the treatment of people with borderline personality disorder; Reference Abraham and Calabrese11 polypharmacy is also common. Reference Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan and Bohus1 The aims of this work were to update the previous Cochrane Collaboration review on this topic, Reference Binks, Fenton, McCarthy, Lee, Adams and Duggan12 and to systematically search for, evaluate and appraise high-quality evidence of the effect of drug treatment on core symptoms and associated psychiatric pathology.

Method

Studies were identified from searches up to June 2008 in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, National Research Records, BIOSIS, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, the Applied Social Sciences Index of Abstracts, ISI Web of Knowledge, System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe, International Bibliography of Social Science, Copac and Dissertation Abstracts. The Cochrane maximum sensitive search strategy was used where possible, and ‘borderline personality disorder’ was employed as the key or title word. The following trial registers were searched via the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform: the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry, ClinicalTrials.gov and the Australian Clinical Trials Registry. Additionally, cross-references from relevant literature were traced, and researchers in the field were contacted by email and asked for unpublished data. There was no language restriction.

All randomised comparisons testing pharmacological interventions in borderline personality disorder on a long-term basis (i.e. continuous medication) were included. Likewise, data from randomised crossover studies up to the point of first crossover were eligible. At least 70% of study participants had to have a formal diagnosis of borderline personality disorder according to DSM–III, DSM–III–R, DSM–IV or DSM–IV–TR. Both provider and recipient masking (blinding) were required. Only articles providing the data necessary for effect size calculation for at least one of the primary or secondary outcomes were included. Primary outcomes were overall disorder severity and severity of core symptoms as defined by DSM. The distinct borderline personality disorder criteria were assessed separately, but they were also subsumed into four clusters of symptoms: affective dysregulation (affective instability, chronic feelings of emptiness, inappropriate anger), cognitive–perceptual symptoms (identity disturbance, stress-related paranoia/dissociation), impulsive–behavioural dyscontrol (self-mutilating or suicidal behaviour, impulsivity) and interpersonal problems (frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, unstable relationships). Secondary outcomes were depression, anxiety, global scores reflecting severity of general psychiatric pathology, mental health status, attrition and adverse events.

Citations were independently inspected by two reviewers to establish whether each study met the inclusion criteria. If the reviewers' judgements did not match, an adjudicator was called in to discuss whether these criteria had been met. Data from included studies were then independently extracted by two reviewers, and the mapping of assessment scales provided by the primary studies to the outcomes of interest was discussed. Discrepancies were solved by discussion and appeal to a third person, as in the study identification process. The methodological quality of the studies was independently assessed by two reviewers with respect to threats to internal validity, using the new Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias assessment tool. Reference Higgins, Altman, Higgins and Green13 Only trials of high or moderate quality were included.

All calculations were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.0 for Windows. (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford UK; www.cc-ims.net/RevMan). For continuous outcomes, standardised mean differences (SMD) were calculated on the basis of post-treatment results. Thus, results attained using different assessment instruments were converted to a uniform scale, facilitating comparability and pooling. Where only change data were available, standardised mean changes (SMC) were calculated on the basis of mean baseline to post-treatment assessment changes with standard deviations. If only group mean changes and pairwise P-values of variance analyses were available, the standard errors were estimated on the basis of the P-values, Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman, Higgins and Green14 and the generic inverse variance method was used for pooling. That way, non-standardised treatment effects (mean change difference, MCD) were obtained. For dichotomous outcomes the risk ratio (RR) was computed. For all continuous outcomes reflecting symptom severity, negative values indicate a decrease and therefore favour the active group (or, where there were two active groups, the first in line). For continuous measures of mental health status, positive values are favourable, indicating better functioning. For dichotomous outcomes, values below 1 indicate a smaller risk of negative outcome if having received the active drug or the first treatment in line, respectively. For each effect estimate, and the pooled effect estimates, 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Effect sizes were calculated on the basis of intention-to-treat data wherever possible. Where only available case analysis (ACA) data were reported, continuous outcome effect sizes were calculated on the basis of the ACA data. For dichotomous data provided only for study completers, the number of patients not completing per protocol in each group was added to the group of participants with unfavourable results. Attrition was examined by comparing tolerability of treatment in terms of the risk of non-completion of treatment in both study groups.

In some reports several measures were provided for the same outcome (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores for depression). To avoid an inflation of type 1 error, only one relevant result per outcome variable was used for effect size calculation for each study. Assessment instruments specific to borderline personality disorder were the first choice for outcome assessment. If none was available, the measure most often used in the whole pool of included studies was chosen for effect size calculation, in order to minimise the heterogeneity of outcomes in form and content. If there was no difference in the frequency of use, we chose the measure that, by mutual agreement of both data-extracting reviewers, most adequately reflected that particular outcome in patients with borderline personality disorder. Self-rated measures were preferred.

Statistical heterogeneity was investigated by calculating the I 2 value. If this score exceeded 75%, the effect estimates were considered too heterogeneous, and study data were not pooled. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman15 If there was no evidence of substantial heterogeneity, pooled effect sizes were calculated using a random effects model (continuous data: inverse variance according to DerSimonian & Laird; dichotomous data: Mantel & Haenszel). Reference DerSimonian and Laird16,Reference Mantel and Haenszel17

Results

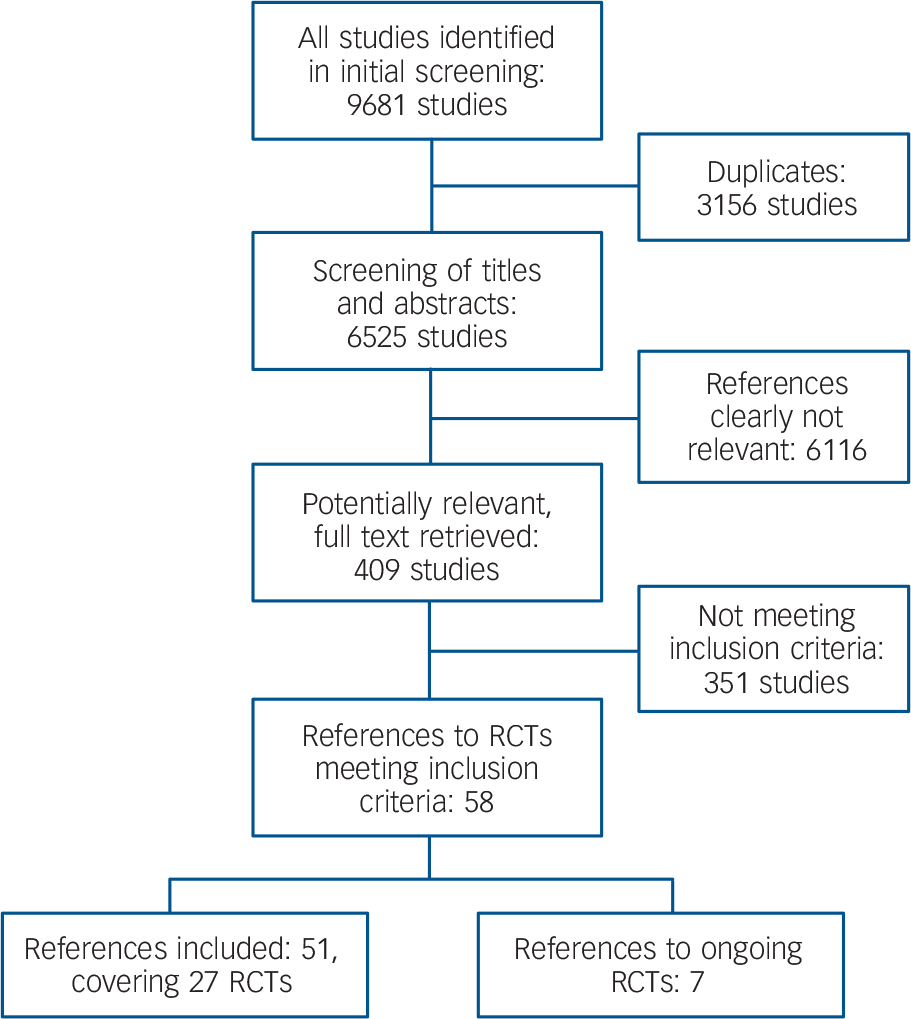

The study searches generated 9681 references, 3156 of which were identified as duplicates (Fig. 1). After screening of titles and abstracts of the remaining 6525 references, 409 citations merited closer inspection. Of these, 351 citations were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Seven references referred to ongoing trials for which data were not yet available. Fifty-one citations were included, relating to 27 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (primary references published between 1979 and 2008). Reference Bogenschutz and Nurnberg18–Reference Zanarini44 Thus, 17 more trials were included than in the preceding Cochrane review, Reference Binks, Fenton, McCarthy, Lee, Adams and Duggan12 in which the most recent primary study dated from 2001. Since that date a remarkable shift of research interest in borderline personality disorder treatment has taken place: second-generation antipsychotics and mood stabilisers have become the focus of research, whereas first-generation antipsychotics are now of lesser interest.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of study selection (RCT, randomised controlled trial).

Description of studies

The main study characteristics are given online in Table DS1 and are outlined in Table 1. In total, data for 1714 participants were included, with study samples varying in size between 16 and 314 participants. Most trials included both female and male patients, and most were conducted in out-patient settings. Baseline assessments of overall mental health status and/or severity of borderline personality disorder in particular indicated mild to moderate levels of impairment of functioning. The most common exclusion criteria were comorbid psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, current major depressive disorder and substance-related disorders. Patients with current suicidal ideation were not eligible for almost half of the included trials.

Table 1 Characteristics of included randomised comparisons

| Study | Treatments | Mean dose |

|---|---|---|

| Bogenschutz 2004 Reference Bogenschutz and Nurnberg18 | Olanzapine v. placebo | 6.9 mg/day |

| De la Fuente 1994 Reference De la Fuente and Lotstra19 | Carbamazepine v. placebo | Blood levels 6.4-7.1 μg/ml |

| EliLilly 2007a Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini22 | Olanzapine v. placebo | 7.1 mg/daya |

| EliLilly 2007b 21 | Olanzapine v. placebo | 6.7 mg/a |

| Frankenburg 2002 Reference Goldberg, Schulz, Schulz, Resnick, Hamer and Friedel23 | Valproate semisodium v. placebo | 850 mg/day |

| Goldberg 1986 Reference Goldberg, Schulz, Schulz, Resnick, Hamer and Friedel23 | Thiothixene v. placebo | 8.7 mg/day |

| Hallahan 2007 Reference Hallahan, Hibbeln, Davis and Garland24 | Omega-3 fatty acids v. placebo | 1.2 g/day of E-EPA + 0.9 g/day of DHA |

| Hollander 2001 Reference Hollander, Allen, Lopez, Bienstock, Grossman and Siever25 | Valproate semisodium v. placebo | Mean blood valproate level 64.6 μg/ml |

| Leone 1982 Reference Leone26 | Loxapine | 14.4 mg/day |

| Chlorpromazine v. placebo | 110 mg/day | |

| Linehan 2008 Reference Linehan, McDavid, Brown, Sayrs and Gallop27 | Olanzapine v. placebo | 4.5 mg/dayb |

| Loew 2006 Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28 | Topiramate v. placebo | 200 mg/day |

| Montgomery 1979 Reference Montgomery, Montgomery, Janyanthi, Roy, Shaw and McAuley30 | Flupentixol decanoate i.m. v. placebo | 20 mg/4 weeks |

| Montgomery 1981 Reference Montgomery, Roy and Montgomery29 | Mianserin v. placebo | 30 mg/day |

| Nickel 2004 Reference Nickel, Nickel, Mitterlehner, Tritt, Lahmann and Leiberich31 | Topiramate v. placebo | 250 mg/day |

| Nickel 2005 Reference Nickel, Nickel, Kaplan, Lahmann, Muhlbacher and Tritt32 | Topiramate v.placebo | 250 mg/day |

| Nickel 2006 Reference Nickel, Muehlbacher, Nickel, Kettler, Pedrosa and Bachler33 | Aripiprazole v. placebo | 15 mg/day |

| Pascual 2008 Reference Pascual, Soler, Puigdemont, Perez-Egea, Tiana and Alvarez34 | Ziprasidone v. placebo | 81 mg/day |

| Rinne 2002 Reference Rinne, van den Brink, Wouter and van Dyck35 | Fluvoxamine v. placebo | 150 mg/day |

| Salzman 1995 Reference Salzman, Wolfson, Schatzberg, Looper, Henke and Albanese36 | Fluoxetine v. placebo | 40 mg/day |

| Simpson 2004 Reference Simpson, Yen, Costello, Rosen, Begin and Pistorello37 | Fluoxetine v. placebo | 40 mg/dayb |

| Soler 2005 Reference Soler, Pascual, Campins, Barrachina, Puigdemont and Alvarez38 | Olanzapine v. placebo | 8.9 mg/dayb |

| Soloff 1993 Reference Soloff, Cornelius, George, Nathan, Perel and Ulrich40 | Haloperidol | 3.9 mg/day |

| Phenelzine sulfate v. placebo | 60.45 mg/day | |

| Soloff 1989 Reference Soloff, George, Nathan, Schulz, Cornelius and Herring39 | Haloperidol | 4.8 mg/day |

| Amitriptyline v. placebo | 149.1 mg/day | |

| Tritt 2005 Reference Tritt, Nickel, Lahmann, Leiberich, Rother and Loew41 | Lamotrigine v. placebo | 200 mg/day |

| Zanarini 2001 Reference Zanarini and Frankenburg42 | Olanzapine v. placebo | 5.3 mg/day |

| Zanarini 2003 Reference Zanarini44 | Omega-3 fatty acids v. placebo | 1 g/day of E-EPA |

| Zanarini 2004 Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Parachini43 | Olanzapine | 3.3 mg/day |

| Fluoxetine | 15.0 mg/day | |

| Olanzapine + fluoxetine | 3.2 mg/day olanzapine + 12.7 mg/day fluoxetine |

The study pool comprised sixteen different comparisons of drug v. placebo, four of drug v. drug and two of drug v. a combination of drugs. Whereas older studies focused mainly on first-generation antipsychotics and antidepressants, since the mid-1990s second-generation antipsychotics, mood stabilisers and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have gained more attention. Study durations ranged from 5 weeks to 24 weeks, with a mean duration of approximately 84 days (s.d. = 54.7), i.e. 12 weeks.

Drug v. placebo comparisons

In included trials, first- and second-generation antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, antidepressants and omega-3 fatty acids were compared with placebo. All identified significant evidence of effectiveness is reviewed in online Table DS2. Full details of all significant and non-significant findings are additionally outlined in the original Cochrane Collaboration systematic review, Reference Stoffers, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer and Lieb45 or can be obtained from the authors.

First-generation antipsychotics

The comparisons of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) with placebo yielded significant effects for haloperidol in the reduction of anger (SMD = −0.46, 95% CI −0.84 to −0.09; two RCTs, n = 114), Reference Soloff, George, Nathan, Schulz, Cornelius and Herring39,Reference Soloff, Cornelius, George, Nathan, Perel and Ulrich40 and flupentixol decanoate in the reduction of suicidal behaviour (RR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.92, one RCT, n = 37). Reference Montgomery, Montgomery, Janyanthi, Roy, Shaw and McAuley30 No proof of efficacy was found for thiothixene for any outcome. Reference Goldberg, Schulz, Schulz, Resnick, Hamer and Friedel23 Tolerability between active and placebo treatment did not differ in any comparison.

Second-generation antipsychotics

Among second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), aripiprazole was found to have both significant effects in the reduction of the core pathological symptoms of borderline personality disorder, as investigated by one trial with 52 participants (anger SMD = −1.14, 95% CI −1.73 to −0.55; psychotic symptoms SMD = −1.05, 95% CI −1.64 to −0.47; impulsivity SMD = −1.84, 95% CI −2.49 to −1.18; interpersonal problems SMD = −0.77, 95% CI −1.33 to −0.20), as well as in the treatment of associated pathology (depression SMD = −1.25, 95% CI −1.85 to −0.65; anxiety SMD = −0.73, 95% CI −1.29 to −0.17; general severity of psychiatric pathology SMD = −1.27, 95% CI −1.87 to −0.67). Reference Nickel, Muehlbacher, Nickel, Kettler, Pedrosa and Bachler33 Six trials compared olanzapine with placebo; among these were two large studies including approximately 300 participants each. 20,21 Unfortunately, the different formats of result reporting (end-point v. change data) did not allow pooling of all study estimates for the majority of outcomes. The pooled mean change data from three trials involving 631 participants in total yielded significant effects for the reduction of affective instability (SMC = −0.16, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.01), anger (SMC = −0.27, 95% CI −0.43 to −0.12) and psychotic symptoms (SMC = −0.18, 95% CI −0.34 to −0.03). Reference Bogenschutz and Nurnberg18–20 There were also statistically significant benefits for the reduction of anxiety (MCD = −0.22, 95% CI −0.41 to −0.03, one RCT, n = 274). 20 However, results for suicidal ideation were inconsistent: two study estimates revealed a significantly lower decrease of suicidal ideation with olanzapine compared with placebo (SMC = 0.29, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.50, two RCTs, n = 340); Reference Bogenschutz and Nurnberg18,21 of the remaining three available effect estimates for this comparison and outcome, two also indicated unfavourable outcomes for olanzapine treatment compared with placebo (SMD = 0.15, 95% CI −0.36 to 0.65, one RCT, n = 60; Reference Soler, Pascual, Campins, Barrachina, Puigdemont and Alvarez38 RR of self-harming behaviour 1.20, 95% CI 0.50 to 2.88, one RCT, n = 24), Reference Linehan, McDavid, Brown, Sayrs and Gallop27 whereas the third one did not (MCD = −0.10, 95% CI −0.20 to 0.00, one RCT, n = 287). 20 For ziprasidone treatment no significant effect was found for any outcome. Reference Pascual, Soler, Puigdemont, Perez-Egea, Tiana and Alvarez34

Mood stabilisers

Beneficial effects were found for the mood stabilisers valproate semisodium (divalproex sodium), lamotrigine and topiramate, but not for carbamazepine. Reference De la Fuente and Lotstra19 Valproate semisodium was tested in two small RCTs. Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini22,Reference Hollander, Allen, Lopez, Bienstock, Grossman and Siever25 There were significant effects on the reduction of interpersonal problems (SMD = −1.04, 95% CI −1.85 to −0.23, one RCT, n = 30) Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini22 and depression (SMD = −0.66, 95% CI −1.31 to −0.01, two RCTs, n = 46). Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini22,Reference Hollander, Allen, Lopez, Bienstock, Grossman and Siever25 One of the two RCTs had a significant effect estimate for the reduction of anger (SMD = −1.83, 95% CI −3.17 to −0.48, one RCT, n = 16), Reference Hollander, Allen, Lopez, Bienstock, Grossman and Siever25 but the second effect estimate was not significant although it also indicated a beneficial tendency (SMD = −0.15, 95% CI −0.91 to 0.61, one RCT, n = 30). Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini22 The effects could not be pooled owing to statistical heterogeneity (I 2 = 78%). Lamotrigine was significantly superior to placebo for the reduction of impulsivity (SMD = −1.62, 95% CI −2.54 to −0.69) and anger (SMD = −1.69, 95% CI −2.62 to −0.75), as investigated in one RCT. Reference Tritt, Nickel, Lahmann, Leiberich, Rother and Loew41 Topiramate was tested in three trials: Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28,Reference Nickel, Nickel, Mitterlehner, Tritt, Lahmann and Leiberich31,Reference Nickel, Nickel, Kaplan, Lahmann, Muhlbacher and Tritt32 there were significant effects on interpersonal problems (SMD = −0.91, 95% CI −1.36 to −0.35, one RCT, n = 56) Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28 and impulsivity (SMD = −3.36, 95% CI −4.44 to −2.27, two RCTs, n = 71). Reference Nickel, Nickel, Mitterlehner, Tritt, Lahmann and Leiberich31,Reference Nickel, Nickel, Kaplan, Lahmann, Muhlbacher and Tritt32 The effect estimates for anger could not be pooled owing to statistical heterogeneity (I 2 = 93%). Data were thus analysed separately for both genders, resulting in more homogeneous effect estimates (I 2 = 0%). The male sample experienced a significant decrease (SMD = −0.65, 95% CI −1.27 to −0.03, n = 42). Reference Nickel, Nickel, Kaplan, Lahmann, Muhlbacher and Tritt32 There was also a significant but larger effect for the female group (SMD = −3.00, 95% CI −3.64 to −2.36, two RCTs, n = 85). Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28,Reference Nickel, Nickel, Mitterlehner, Tritt, Lahmann and Leiberich31 Associated psychopathology was also found to be significantly affected by topiramate, as investigated in one RCT (anxiety SMD = −1.40, 95% CI −1.99 to −0.81; general psychiatric pathology SMD = −1.19, 95% CI −1.76 to −0.61, n = 56). Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28

Antidepressants

There was little evidence of effectiveness for antidepressant treatment. Of all agents tested, there was only one significant effect for the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline in the reduction of depressive pathology (SMD = −0.59, 95% CI −1.12 to −0.06, one RCT, n = 57). Reference Soloff, George, Nathan, Schulz, Cornelius and Herring39 No significant effect was found for mianserin, Reference Montgomery, Roy and Montgomery29 the SSRIs fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, Reference Rinne, van den Brink, Wouter and van Dyck35–Reference Simpson, Yen, Costello, Rosen, Begin and Pistorello37 or the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine sulphate. Reference Soloff, Cornelius, George, Nathan, Perel and Ulrich40

Other drugs

For supplementary omega-3 fatty acids, significant effects were found in one study (n = 49) for the reduction of suicidality (RR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.95) and depressive symptoms (RR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.81). Reference Hallahan, Hibbeln, Davis and Garland24 There was also an effect estimate of a second study (n = 27) for depressive symptoms, Reference Stoffers, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer and Lieb45 but because of different formats of reporting it could not be pooled with the first one. However, these findings also tended towards better results in participants given omega-3 fatty acids (SMD = −0.34, 95% CI −1.15 to 0.46).

Tolerability and safety

Tolerability did not differ for any drug–placebo comparison, i.e. drug treatment was not associated with a higher ratio of non-completers than was placebo treatment. Detailed data on adverse effects were available for olanzapine treatment. Participants treated with this drug were, overall, no more likely to experience any adverse effect than were members of the control group (RR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.28, two RCTs, n = 615). 20,21 However, there was a significant effect of weight gain (SMD = 1.05, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.20, six RCTs, n = 752); Reference Bogenschutz and Nurnberg18,20,21,Reference Linehan, McDavid, Brown, Sayrs and Gallop27,Reference Soler, Pascual, Campins, Barrachina, Puigdemont and Alvarez38,Reference Zanarini and Frankenburg42 increased appetite (RR = 2.78, 95% CI 1.75 to 4.34, two RCTs, n = 615); 20,21 somnolence (RR = 2.97, 95% CI 1.75 to 5.03, two RCTs, n = 615); 20,21 and mouth dryness (RR = 2.24, 95% CI 1.08 to 4.67, two RCTs, n = 615). 20,21 Sedation was found to occur significantly more frequently with olanzapine in one trial (RR = 9.23, 95% CI 2.18 to 39.12, n = 314), 21 with another trial supporting this tendency with a non-significant effect (RR = 1.26, 95% CI 0.44 to 3.66, n = 27); Reference Zanarini and Frankenburg42 owing to statistical heterogeneity, probably stemming from the substantially different sample sizes, these two effects were not pooled. No significant difference was reported for the events of headache, disturbed attention, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, nausea, constipation and nasopharyngitis. Laboratory values were also available, with significant effect estimates for liver transaminase changes (aspartate transaminase change SMD = 0.35, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.52, two RCTs, n = 526; 20,21 alanine transaminase change SMD = 0.46, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.63, two RCTs, n = 530); 20,21 γ-glutamyl transferase change (SMD = 0.26, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.50, one RCT, n = 268); 20 bilirubin changes (total bilirubin change SMD = −0.29, 95 % CI −0.53 to −0.05, one RCT, n = 264; 21 direct bilirubin change SMD = −0.35, 95% CI −0.60 to −0.11, one RCT, n = 158); 21 blood lipids (total cholesterol change SMD = 0.42, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.64, two RCTs, n = 327; 21,Reference Soler, Pascual, Campins, Barrachina, Puigdemont and Alvarez38 low-density lipoprotein cholesterol change SMD = 0.35, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.59, one RCT, n = 259; 21 high-density lipoprotein cholesterol change SMD = −0.28, 95% CI −0.52 to −0.04, one RCT, n = 269; 20 fasting triglycerides change SMD = 0.37, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.64, one RCT, n = 203); 20 prolactin increase (SMD = 0.41, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.59, two RCTs, n = 528); 20,21 and blood cell count changes (as assessed in one RCT with 262 data-sets: leukocytes SMD = −0.40, 95% CI −0.65 to −0.16; segmented neutrophils SMD = −0.39, 95% CI −0.63 to −0.14; basophils SMD = −0.28, 95% CI −0.53 to −0.04; monocytes SMD = −0.28, 95% CI −0.53 to −0.04). There was also a significant decrease in blood calcium (SMD = −0.33, 95% CI −0.57 to −0.09, one RCT, n = 268). 21 The findings of olanzapine effects on platelet counts were inconsistent, however. A significant increase was found by one RCT (SMD = 0.32, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.56, n = 257), 21 and a significant decrease by another (SMD = −0.26, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.01, n = 260). 20 No significant change was found for haemoglobin, albumin, kidney function or circulation parameters. 20

For ziprasidone the ratio of participants experiencing any adverse event, and dizziness, sedation and an ‘uneasy feeling’ in particular, did not differ significantly from placebo-treated participants (n = 60). Reference Pascual, Soler, Puigdemont, Perez-Egea, Tiana and Alvarez34

Adverse effects were also reported in detail for topiramate treatment. There was a significant effect of weight loss (SMD = −0.55, 95% CI −0.91 to −0.19, three RCTs, n = 127). Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28,Reference Nickel, Nickel, Mitterlehner, Tritt, Lahmann and Leiberich31,Reference Nickel, Nickel, Kaplan, Lahmann, Muhlbacher and Tritt32 Data on the frequency of memory problems, trouble in concentrating, headache, fatigue, dizziness, menstrual pain and paraesthesia were also available for one RCT, with no significant difference in frequency between the topiramate and placebo groups. Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28 One trial reported less weight gain caused by haloperidol (SMD = −0.18, 95% CI −0.70 to 0.34, n = 58) and more by phenelzine sulphate treatment (SMD = 0.11, 95% CI −0.39 to 0.61, n = 62) compared with placebo, Reference Soloff, Cornelius, George, Nathan, Perel and Ulrich40 but there was no significant effect.

No detailed data were provided for any other drug v. placebo comparison.

Drug v. drug comparisons

Two FGAs, loxapine and chlorpromazine, were compared in one study with 80 participants. Reference Leone26 Tolerability did not differ significantly. However, there was no usable information on any pathology-related outcome.

Two antidepressants were compared with the FGA haloperidol. The tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline did not differ significantly from haloperidol treatment for any outcome (one RCT, n = 61). Reference Soloff, George, Nathan, Schulz, Cornelius and Herring39 The monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine sulphate, however, proved to be superior to haloperidol in the reduction of depression (SMD = −0.68, 95% CI −1.19 to −0.17), anxiety (SMD = −0.66, 95% CI −1.16 to −0.15) and general psychiatric pathology (SMD = −0.53, 95% CI −1.03 to −0.03), and in improving mental health status (SMD = 0.51, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.01) as investigated in one study (n = 64). Reference Soloff, Cornelius, George, Nathan, Perel and Ulrich40

No significant effect was found for the comparison of the SGA olanzapine with the antidepressant fluoxetine for any pathology-related outcome (one RCT, n = 30). Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Parachini43

Attrition did not differ significantly for any of the investigated drug v. drug comparisons. The loxapine v. chlorpromazine comparison yielded no significant difference for the prevalences of any adverse event, sleepiness, restlessness, muscle spasms or fainting spells. No detailed data were available for the haloperidol v. amitriptyline comparison. Body weight change was not significantly different in haloperidol and phenelzine sulphate treatment. Participants in the olanzapine group had significantly more weight gain than those in the fluoxetine group after treatment (SMD = 0.98, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.76, one RCT, n = 29), Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Parachini43 and mild sedation was more often reported in the olanzapine group (RR = 3.50, 95% CI 1.23 to 9.92, one RCT, n = 30). Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Parachini43 The two groups did not differ significantly concerning the ratio of participants experiencing restlessness.

Drug v. combination of drugs

One trial tested the effects of olanzapine (n = 16) and fluoxetine (n = 14) separately against their combination (n = 15). Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Parachini43 There was no significant difference indicating any benefits from combined treatment v. treatment with olanzapine or fluoxetine alone. Tolerability did not differ significantly. Detailed data were available for body weight change, the frequency of restlessness and mild sedation. There was no significant difference.

Discussion

We identified 27 RCTs concerning the pharmacological treatment of borderline personality disorder. First- and second-generation antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, antidepressants and supplementary omega-3 fatty acids were tested. Beneficial effects of drug treatment were observed for all major core symptom clusters of the disorder as well as for associated psychopathology. Symptoms relating to the interpersonal pathology pattern were significantly affected by the SGA aripiprazole and the mood stabilisers valproate semisodium and topiramate. For the treatment of affective dysregulation symptoms, the evidence suggests the effectiveness of the FGA haloperidol, the SGAs aripiprazole and olanzapine, and mood stabilisers (topiramate, lamotrigine and valproate semisodium). Impulsive–behavioural dyscontrol symptoms were shown to be significantly affected by the FGA flupentixol decanoate, the SGA aripiprazole, the mood stabilisers topiramate and lamotrigine, and omega-3 fatty acid supplements. However, the effect estimates for olanzapine on the outcome of self-injuring and suicidal behaviour were inconsistent. There was a significant effect of less amelioration, as two pooled estimates revealed. The tendency to worse results was supported by two more study effects, which unfortunately could not be pooled. A fifth estimate, however, yielded more amelioration by olanzapine treatment. Concerning the treatment of cognitive–perceptual symptoms, evidence of effectiveness was found for the SGAs aripiprazole and olanzapine.

Significantly better results for associated affective pathology were found for SGAs (aripiprazole and olanzapine), mood stabilisers (topiramate and valproate semisodium), amitriptyline and omega-3 fatty acids. Additionally, the SGA aripiprazole was found to reduce general psychiatric pathology to a significant extent, as was topiramate. Notably, among all antidepressants investigated in RCTs up to now, evidence of effectiveness exists for the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline (depressive pathology only), but not for any SSRI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor or mianserin regarding any outcome.

With exception of the phenelzine sulphate v. haloperidol comparison, there was no evidence of different effectiveness for any direct comparison of drugs (loxapine v. chlorpromazine, haloperidol v. amitriptyline, olanzapine v. fluoxetine). Phenelzine sulphate was found to be significantly superior to haloperidol in the reduction of affective pathology and general psychiatric pathology associated with borderline personality disorder, and in ameliorating the overall level of functioning.

Notably, no evidence of effectiveness was found for several borderline personality disorder symptoms – avoidance of abandonment, chronic feelings of emptiness, identity disturbance and dissociation. This finding may be the result of the use of non-disorder-specific assessment instruments in most studies, but also reflects that these symptoms may not be treatable by pharmacotherapeutic interventions, but rather by psychotherapy. Reference Stoffers, Völlm and Lieb46

Quality of evidence

In the presence of a multitude of different comparisons and outcome variables, most findings are based on single effect estimates only. The use of different assessment instruments for the same outcome variable rendered comparability and interpretability even more difficult and increased statistical heterogeneity. Owing to different formats of outcome reporting (e.g. post-treatment results v. mean changes, continuous v. dichotomous data), different kinds of effect sizes had to be used, rendering both the pooling and comparing of findings difficult. Additionally, the sample sizes were rather small (with the exception of two large trials with more than 300 participants each), 20,21 ranging from n =4 to n = 40. Reference Hollander, Allen, Lopez, Bienstock, Grossman and Siever25,Reference Leone26 The power to detect significant effects was therefore low, despite our attempts to enhance power by pooling study estimates.

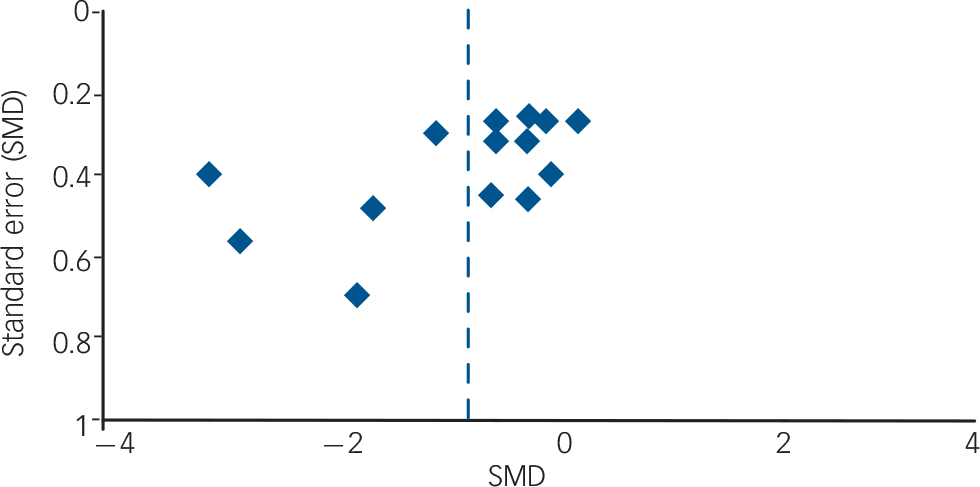

The overall robustness of findings must also be considered low. Further RCT findings are likely to affect the actual results, especially if including larger study samples, since the overall power would thus be enhanced and the detection of significant effects made more likely. However, no additional RCT with matching comparisons is to be expected in the immediate future: most ongoing trials are testing different drugs, such as the SGA quetiapine, the SSRI sertraline or the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone. Reference Stoffers, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer and Lieb45 On the other hand, owing to the small number of effect estimates per specific comparison, it is difficult to judge the actual publication bias (e.g. by funnel plots). A funnel plot for all drug v. placebo comparisons concerning the outcome ‘anger’ was drawn (Fig. 2), but it cannot clearly be judged from this figure whether publication bias is present or not, especially since different kinds of drug–placebo comparisons are involved. However, the lack of published negative, non-significant findings is much more likely. Reference Chan, Hrobjartsson, Haahr, Gotzsche and Altman47,Reference Scherer, Langenberg and von Elm48 Despite our best efforts to avoid publication bias by searching for all published and unpublished studies without language restrictions, we were unable to include any unpublished data.

Fig. 2 Funnel plot (SMD, standardised mean difference).

Outcome assessment was mostly restricted to target variables that were not assessed with instruments specific to borderline personality disorder. For example, psychotic pathology was a common outcome and non-specific assessment instruments were frequently used, such as the Symptom Checklist–90 subscale ‘psychoticism’, but psychotic symptoms specific to borderline personality disorder, for example stress-related paranoid ideation and dissociation, were not assessed. Furthermore, some domains of the core pathology of the disorder were almost completely neglected, e.g. affective instability, dissociation and chronic feelings of emptiness. Fortunately, relevant assessment instruments have now been developed reflecting each of the core criteria of borderline personality disorder, e.g. the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index, Reference Arntz, van den Hoorn, Cornelis, Verheul, van den Bosch and de Bie49 the Clinical Global Impression for Borderline Personality Disorder scale, Reference Perez, Barrachina, Soler, Pascual, Campins and Puigdemont50 and the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder, Reference Zanarini, Vujanovic, Parachini, Boulanger, Frankenburg and Hennen51 and have been used in some recent studies. 20,21,Reference Pascual, Soler, Puigdemont, Perez-Egea, Tiana and Alvarez34,Reference Rinne, van den Brink, Wouter and van Dyck35 Most studies provided only a fragmentary outcome pattern, making the concealment of non-significant findings likely. We tried to address this by initially defining a comprehensive set of relevant outcome variables that are directly (primary outcomes) or indirectly (secondary outcomes) associated with borderline personality disorder. Therefore, not only significant findings but also non-significant effects should equally be considered (for detailed data see Stoffers et al). Reference Stoffers, Völlm, Rücker, Timmer and Lieb45

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Of concern regarding applicability to clinical settings might be the rather strict psychiatric exclusion criteria of most primary studies, and the severity of illness of study participants. Patients who were acutely suicidal were not eligible in the majority of trials, and the overall severity of illness varied between studies, mostly from mild to moderate. Besides, patients with comorbid schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders, bipolar disorders, alcohol or drug dependence and sometimes merely alcohol or drug misuse were often not eligible for study participation. What is more, a current major depressive episode or severe depression was also a criterion of exclusion in the majority of trials. As comorbid Axis I disorders are highly prevalent in people with borderline personality disorder, especially mood disorders (96.9%) and substance use disorders (62.1%), Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, Reich and Silk52 their exclusion may render applicability difficult. However, eating disorders – highly prevalent in borderline personality disorder (53%) Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen, Reich and Silk52 – were not a reason for exclusion in any study apart from two that excluded patients with any comorbid Axis I disorder. Reference De la Fuente and Lotstra19,Reference Salzman, Wolfson, Schatzberg, Looper, Henke and Albanese36 Anxiety disorders, prevalent in 89% of people with borderline personality disorder, 53 were excluded in only two trials (current post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder or obsessive–compulsive disorder). 20,21 In nine studies only women were included, Reference Frankenburg and Zanarini22,Reference Loew, Nickel, Muehlbacher, Kaplan, Nickel and Kettler28,Reference Nickel, Nickel, Mitterlehner, Tritt, Lahmann and Leiberich31,Reference Rinne, van den Brink, Wouter and van Dyck35,Reference Simpson, Yen, Costello, Rosen, Begin and Pistorello37,Reference Tritt, Nickel, Lahmann, Leiberich, Rother and Loew41–Reference Zanarini44 whereas the remaining study samples consisted of both male and female patients. In order to allow for judgement of applicability of the review findings to specific situations, we tried to specify exactly and describe all studies with regard to their characteristics (see online Table DS1).

Study duration ranged from 32 days to 24 weeks, with a mean duration of approximately 12 weeks. These observation periods may be sufficient to be predictive of efficacy in a single patient; however, drug treatment often lasts longer in clinical settings. Therefore, as well as benefits, adverse effects must be monitored carefully. As yet there is no double-blind RCT available concerning the long-term efficacy of the investigated drugs. Another difference from the clinical setting may be that patients often receive several psychotropic drugs at the same time; polypharmacy is common. Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Hennen and Silk3 With the exception of the comparison of combined olanzapine and fluoxetine treatment with olanzapine or fluoxetine treatment alone, Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Parachini43 there is no report of a randomised controlled investigation of polypharmacological treatment. Therefore, it should always be considered that the administration of several drugs is not empirically supported by any RCT, nor, to our knowledge, by any trial of lower evidence level either, and should be avoided whenever possible.

With the exception of three trials in which all the patients were undergoing dialectical behaviour therapy, Reference Linehan, McDavid, Brown, Sayrs and Gallop27,Reference Simpson, Yen, Costello, Rosen, Begin and Pistorello37,Reference Soler, Pascual, Campins, Barrachina, Puigdemont and Alvarez38 study participants did not receive specific concomitant psychotherapy. However, the number of trials and effect estimates per comparison and outcome did not permit making up subgroups such as ‘concomitant psychotherapy’ and ‘no concomitant psychotherapy’ to compare differential treatment effects. There is a need to investigate possible additive effects of pharmacotherapy to psychotherapy and vice versa in the future.

Implications for practice and research

Conclusions from the studies reported here have been drawn cautiously because of the limitations discussed above. However, considering this evidence together with clinical experience, antidepressants such as SSRIs cannot further be recommended as first-choice treatment for affective dysregulation and impulsive–behavioural symptoms, nor can low-dose antipsychotics be advised for cognitive–perceptual symptoms as earlier recommended by the American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines; 10,Reference Oldham54 see also Abraham & Calabrese. Reference Abraham and Calabrese11 These guidelines are based on literature searches covering research published up to 1998. Since then 16 more RCTs have been published and are covered in our review. On the basis of the up-to-date evidence, SSRI treatment can only be recommended if the patient is experiencing a major depressive episode or another comorbid condition requiring antidepressant treatment. In contrast, the currently available RCTs investigated in this review suggest mood stabilisers (topiramate, valproate semisodium, lamotrigine) as first-line treatments for affective dysregulation symptoms, and also show positive results for SGAs (aripiprazole, olanzapine) and the FGA haloperidol. With respect to impulsive–behavioural dyscontrol symptoms, mood stabilisers (lamotrigine, topiramate) should be given. There are also favourable results for omega-3 fatty acid supplementation, and, to a lesser extent, for the FGA flupentixol decanoate. Findings regarding SGAs in the treatment of impulsive–behavioural dyscontrol symptoms are diverse. Aripiprazole has beneficial effects on overall impulsivity. For olanzapine, however, the majority of available RCTs indicate unfavourable effects with regard to self-mutilating and suicidal behaviour. Additionally, the SGAs (aripiprazole, olanzapine) should be the first choice for treating cognitive–perceptual symptoms. Up to now, the research base lacks evidence that people with borderline personality disorder benefit from SSRI treatment. However, if there is a prevailing major depressive episode or comparable depressive disorder, the use of SSRIs may be appropriate for antidepressant treatment. Appropriate prescribing guidelines should be followed depending on the comorbid condition. Whether and to what extent patients with borderline personality disorder and comorbid depressive disorder would benefit from SSRI treatment cannot be answered in this review, since placebo-controlled RCTs of SSRI treatment in such samples are lacking.

In January 2009 the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline for borderline personality disorder recommended that:

‘drug treatment should not be used specifically for borderline personality disorder or for the individual symptoms or behaviour associated with the disorder (for example, repeated self-harm, marked emotional instability, risk-taking behaviour and transient psychotic symptoms)’ (p. 270). 53

It is of note that this comprehensive guideline recognises evidence for the reduction of specific symptoms with some pharmacological treatments, but that the final recommendations do not reflect this evidence. Although more robust findings would certainly be desirable, and we appreciate concerns related to giving strong recommendations, we suggest considering a reassessment of these recommendations, as there actually is encouraging evidence of the effectiveness of drug treatment for individual symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Pharmacotherapeutic treatment of such disorder should always be targeted at defined specific symptoms. As yet there is no evidence of beneficial effects of polypharmacotherapeutic treatment, which should therefore be avoided if possible. In the treatment of borderline personality disorder, the toxic effects of overdosing (e.g. with tricyclic antidepressants) and the potential for misuse or substance dependence (e.g. hypnotics and sedatives) must be considered. Especially in the presence of comorbid eating disorders, possible effects on body weight changes (especially weight gain in olanzapine treatment and weight loss in topiramate treatment) should be taken into account, and each possible adverse effect should be discussed by the treating physician and the patient together (shared decision-making). Drug treatment should last for a sufficient period to judge whether there are any benefits, and should be stopped if there is no clear effect.

For research, replicative studies for all comparisons are desirable in order to enhance the robustness of findings. Owing to the huge heterogeneity of outcome variables and assessment instruments, a consensus on a minimum set of therapy outcome variables that are most likely to be of interest for any patient with borderline personality disorder would be desirable. Outcome assessment should be more specific and sensitive to symptoms relevant to this disorder. However, some DSM–IV criteria embrace several symptoms, e.g. the criterion of stress-related paranoid ideation or dissociation. The possibility of a more differentiated outcome assessment might stimulate further research on drugs that may affect core symptoms, which have so far been neglected by existing RCTs. The investigation of drugs targeting affective instability, an important hallmark of borderline personality disorder, would be of particular interest. Other drugs under consideration for use in this disorder could not be included in this review as reports of RCTs are not yet available; however, we are aware of some ongoing trials, the results of which will, we hope, be included in subsequent updates of this review. Additionally, there are findings from lower-level evidence studies on further FGAs and SGAs (e.g. trifluoperazine, clozapine, quetiapine, risperidone), mood stabilisers (e.g. valproate semisodium extended release, lithium, oxcarbazepine), antidepressants (e.g. tranylcypromine, reboxetine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, desipramine and imipramine), anxiolytics (alprazolam), the opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone, and miscellaneous other drugs (e.g. clonidine or riluzole). Reference Herpertz, Zanarini, Schulz, Siever, Lieb and Moller55

Outcome assessment should also embrace a thorough, standardised assessment of adverse events, as spontaneous reporting by patients may not be as valid and comprehensive. Additionally, patients with comorbid Axis I disorders should not be excluded, as psychiatric comorbidity is common in borderline personality disorder. Longer observation periods would be desirable to enhance external validity and the applicability of findings to primary care settings. Additionally, the combination of pharmacotherapy with psychotherapy should gain more attention in future research endeavours.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant no. 01KG0609) to K.L., from the research committee of the University Medical Centre, Freiburg, to J.S. and K.L., and from the German Research Foundation (grant no. FOR 534 Schw 821/2-2) to G.R.

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the previous version of this Cochrane Collaboration, Claire Binks, Mark Fenton, Lucy McCarthy, Tracy Lee, Clive Adams and Conor Duggan. In addition, we are grateful to the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group at Bristol, especially to Jane Dennis and Jo Abbott, and the German Cochrane Centre for supporting this work. We also thank Nicolas Rüsch for translating studies during the study selection phase.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.