Maternal prenatal smoking has been consistently associated with conduct disorder and delinquency (Reference Fergusson, Woodward and HorwoodFergusson et al, 1998; Reference Maughan, Taylor and TaylorMaughan et al, 2001) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Reference Mick, Biederman and FaraoneMick et al, 2002; Reference Thapar, Fowler and RiceThapar et al, 2003) in children and adolescents. Associations remain after controlling for confounding variables such as socio-economic status, maternal age, birth weight and maternal psychopathology (Reference Fergusson, Woodward and HorwoodFergusson et al, 1998; Reference Brennan, Grekin and MednickBrennan et al, 1999) and have been described for both males and females (Reference Fergusson, Woodward and HorwoodFergusson et al, 1998; Reference Maughan, Taylor and TaylorMaughan et al, 2001). Several reasons for this association have been suggested, including direct effects of nicotine on the developing foetus (Reference Cornelius and DayCornelius & Day, 2000) and even genetic mediation (Reference Fergusson, Woodward and HorwoodFergusson et al, 1998; Reference Brennan, Grekin and MednickBrennan et al, 1999). Antisocial behaviour and ADHD commonly covary, with evidence that ADHD behaves as a risk factor for subsequent antisocial behaviour (Reference Fergusson and HorwoodFergusson & Horwood, 1995; Reference Taylor, Chadwick and HeptinstallTaylor et al, 1996). Thus, it has been suggested that the association between antisocial behaviour and maternal prenatal smoking may arise indirectly, mediated by the influence of prenatal smoking on ADHD, and the comorbidity between antisocial behaviour and ADHD (Reference Thapar, Fowler and RiceThapar et al, 2003). Comorbidity between ADHD and antisocial behaviour appears to be largely due to the influence of the same genes on the two phenotypes (Reference Silberg, Rutter and MeyerSilberg et al, 1996; Reference Thapar, Fowler and RiceThapar et al, 2003), although there is some evidence that environmental risk factors may also contribute (Reference Burt, Krueger and McGueBurt et al, 2001).

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether maternal prenatal smoking contributes to the comorbidity between antisocial behaviour and ADHD, or whether the association between maternal prenatal smoking and antisocial behaviour is mediated by ADHD, given the evidence that ADHD may increase the risk of antisocial behaviour (Reference Schachar, Tannock, Rutter and TaylorSchachar & Tannock, 2002).

METHOD

Participants

The participants were a part of CaStaNET (Cardiff Study of All Wales and North West England Twins), a population-based twin register. The twins in this study were a sample of school age born between 1980 and 1991 in Greater Manchester (Reference Thapar, Harrington and RossThapar et al, 2000). At the time of the study these twins were aged 5-18 years. Of the 2846 families who were sent questionnaires, 2082 (73%) returned completed forms. Zygosity was determined using parental responses to a twin similarity questionnaire, with an accuracy of 95% (Reference Cohen, Dibble and GraweCohen et al, 1975). Owing to ambiguous responses 162 twins were not assigned zygosity; 731 monozygotic twin pairs (383 female and 348 male) and 1189 dizygotic twin pairs (313 female, 276 male, and 600 opposite gender) were identified. However, 8 monozygotic and 16 dizygotic twin pairs whose mothers did not provide data regarding their prenatal smoking were eliminated from the analysis, resulting in a final sample of 723 monozygotic and 1173 dizygotic twin pairs. The age distribution of the twins in this analysis was: 5-9 years, 34.4%; 10-14 years, 47.4%; and 15+ years, 18.2%.

Measures

Parents were asked to complete the Rutter A scale (Reference Rutter, Rutter, Tizard and WhitmoreRutter, 1970), an extensively used, parent report questionnaire with good validity, retest reliability and interrater reliability. Antisocial behaviour in the twins was measured using antisocial items from the scale, which were: ‘does he ever steal things?’, ‘often destroys own or other's belongings’, ‘is often disobedient’, ‘often tells lies’, and ‘bullies other children’. Item scores were summed for each twin. The presence of ADHD was assessed using a modified version of the DuPaul ADHD rating scale (Reference DuPaulDuPaul, 1981), which contained 14 DSM-III-R ADHD symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), and was augmented with four additional items to cover ICD-10 symptoms of hyperkinetic disorder (World Health Organization, 1993; Reference Thapar, Harrington and McGuffinThapar et al, 2001). Scores were regressed for age and gender, and standardised values were calculated prior to genetic analysis to eliminate any inflation of common environment effects across same-gender twins (Reference McGue and BouchardMcGue & Bouchard, 1984).

As a measure of maternal prenatal smoking, mothers were asked to retrospectively report how many cigarettes they smoked daily during their pregnancy according to four categories: non-smokers (0 cigarettes), light smokers (1-10), moderate smokers (11-20) and heavy smokers (over 20).

Statistical analysis

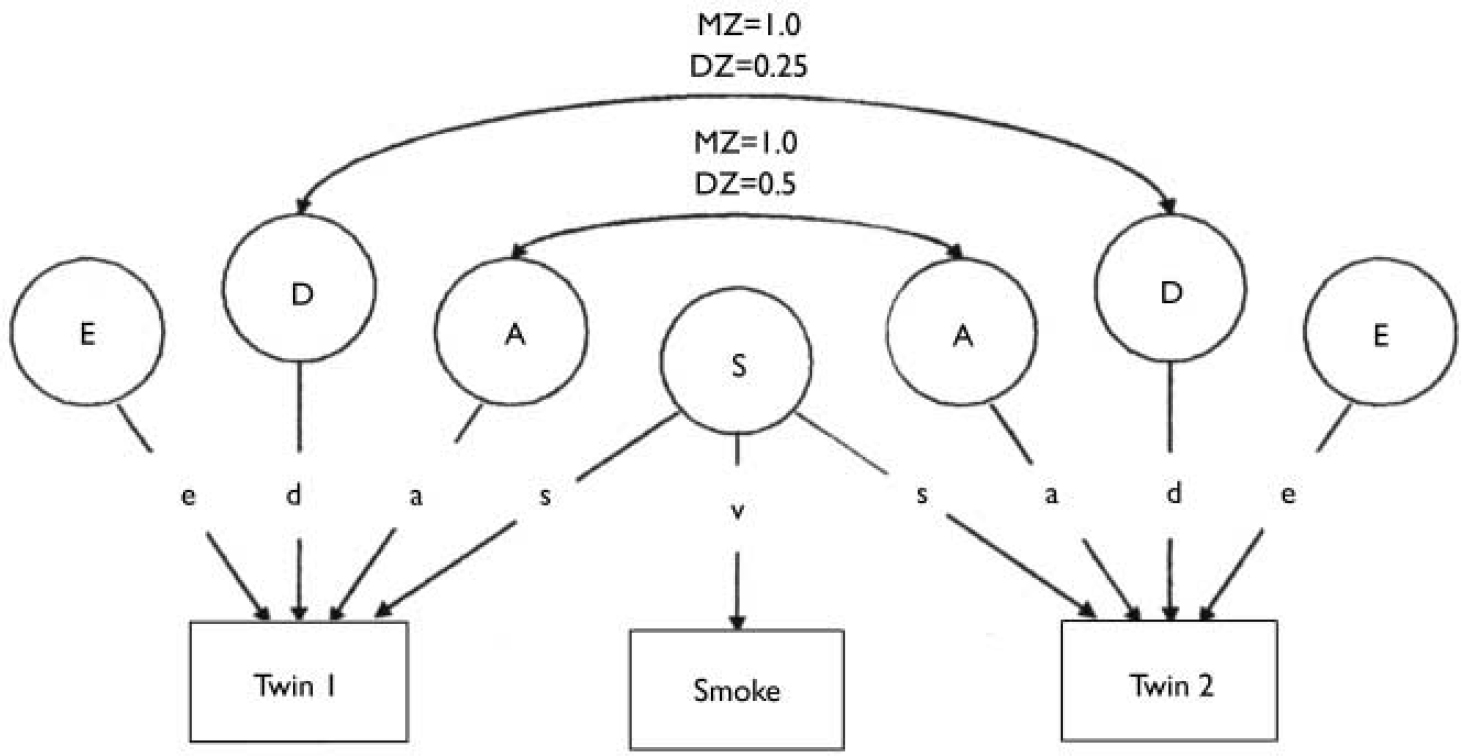

Initial statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 10 for Windows (Reference Kinnear and GrayKinnear & Gray, 2000). Data were double-entered to avoid any bias owing to birth order, and twin order was then selected randomly. The structural equation modelling package Mx (Reference NealeNeale, 1997) was used to test a univariate model that enables us to estimate the proportion of the phenotypic variance attributable to additive genetic effects, non-additive genetic effects, and non-shared environmental effects and maternal prenatal smoking (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 A univariate ADE model which includes maternal smoking effects on the twins' phenotypes (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and antisocial behaviour). A, additive genetic influences; D, non-additive genetic influences; E, non-shared environmental influences; S, latent variable of maternal smoking which contributes to the twins' antisocial phenotype as well as being the sole source of variance for the maternal prenatal smoking score(‘smoke’);MZ, monozygotic; DZ, dizygotic.

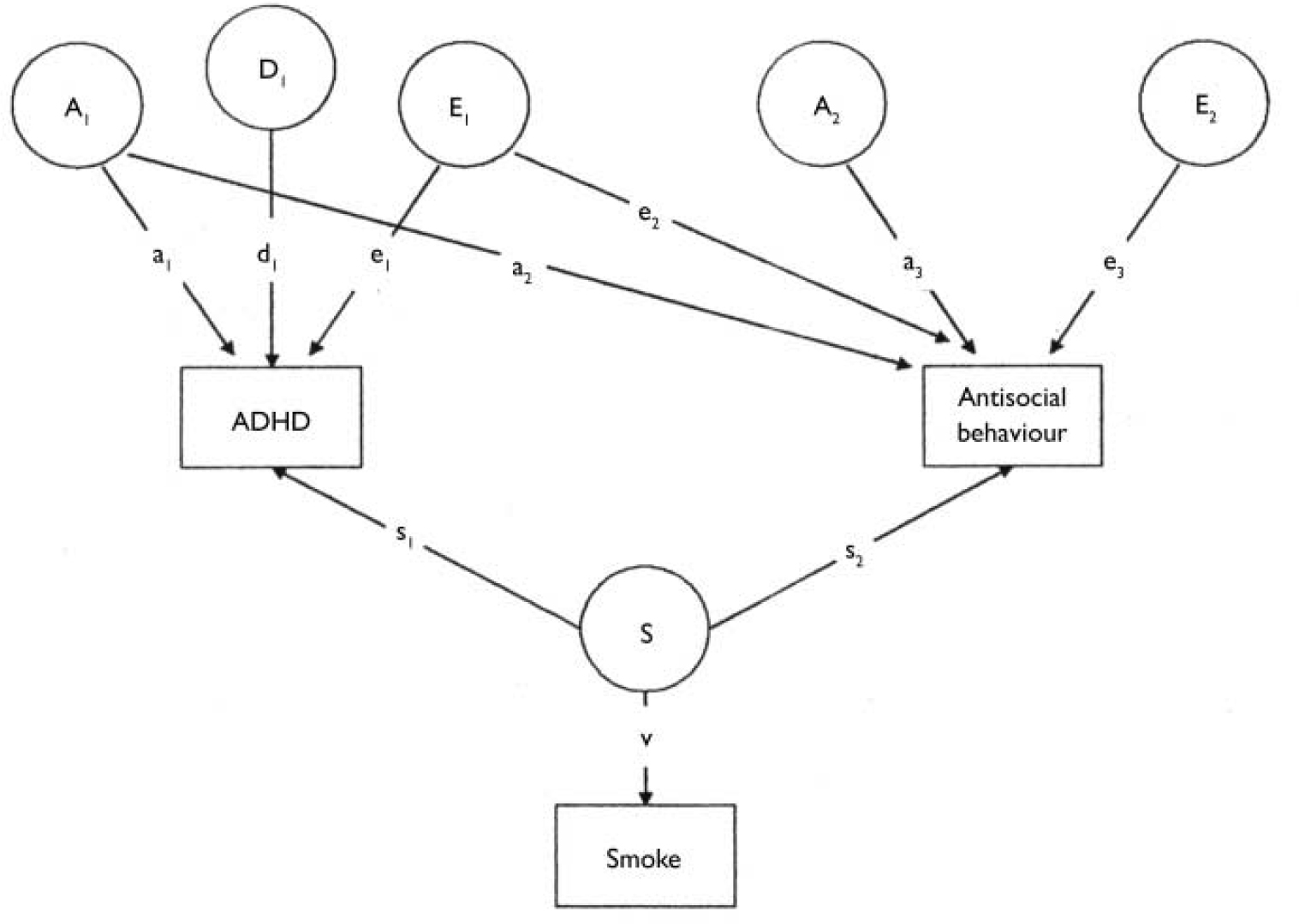

To examine the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking, antisocial behaviour and ADHD two further models were used. The first of these was a Cholesky model, which enabled us to look at the extent to which genes and the environment contribute to both the individual phenotypic variation and the phenotypic covariation between the two. This model also incorporated the measure of maternal prenatal smoking to investigate whether smoking independently contributed to each phenotype (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 A Cholesky decomposition. A1, additive genetic effects with influence on both attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (a1) and antisocial behaviour (a2); A2, additive genetic effects specific to antisocial behaviour (a2); A2, additive genetic effects specific to antisocial behaviour (a3); D1, non-additive genetic effects with influence on ADHD (d1); E1, non-shared environmental effects with influence on both ADHD (e1) and antisocial behaviour (e2); E2, non-shared environmental effects specific to antisocial behaviour (e3); S, prenatal smoking effects; s1, proportion of the variance of ADHD attributable to S; s2, proportion of the variance of antisocial behaviour attributable to S; v, the influence of the latent prenatal smoking variable on the prenatal smoking score.

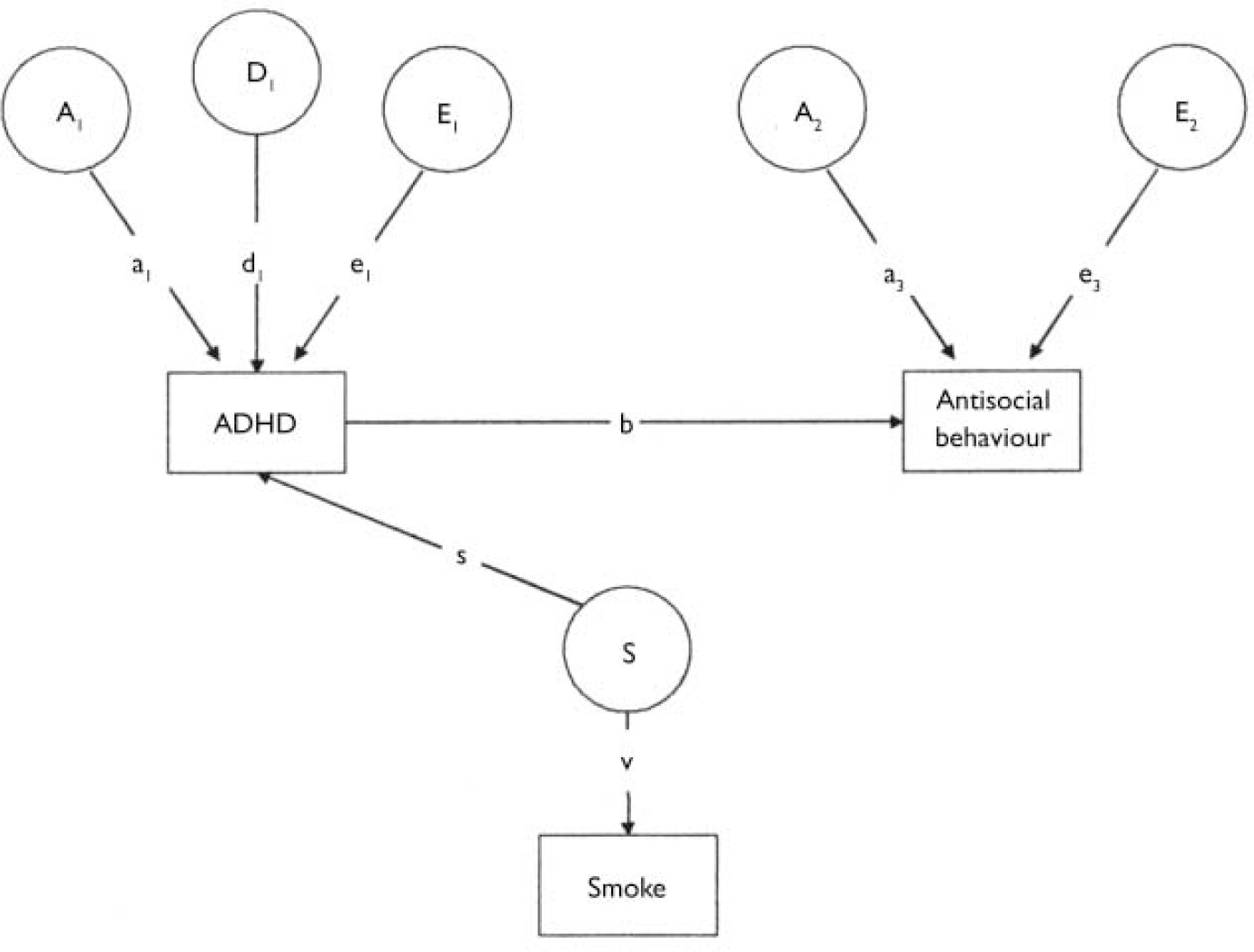

The final model tested was one in which the relationship between maternal smoking in pregnancy and antisocial behaviour is mediated by ADHD, with maternal prenatal smoking increasing the risk of ADHD, and ADHD in turn increasing the risk of antisocial behaviour. This ‘causal’ model is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 A causal model. A1, additive genetic effects influencing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (a1); A2, additive genetic effects influencing antisocial behaviour (a3); D1, non-additive genetic effects influencing ADHD (d1); E1, non-shared environmental effects influencing ADHD (e1); E2, non-shared environmental effects influencing antisocial behaviour (e3); S, prenatal smoking effects; s, proportion of the variance of ADHD attributable to S; v, the influence of the latent prenatal smoking variable on the prenatal smoking score; b, the causal relationship between ADHD and antisocial behaviour.

The fit of all models was tested using χ2 and Akaike's information criterion (AIC), which is calculated as χ2 minus twice the degrees of freedom, and provides an index both of parsimony and goodness of fit. The fit of nested models is also tested and compared with the full model by comparisons of the goodness of fit and also AIC values. The best fitting model was selected as that in which pathways could be dropped without a significant reduction in the fit of the model, and also with the lowest AIC value.

RESULTS

Males scored higher than females for both antisocial behaviour and ADHD symptoms, with means of 1.46 (s.d.=1.87) for antisocial behaviour and 14.47 (s.d.=11.97) for ADHD for males and 0.92 (s.d.=1.47) and 9.30 (s.d.=9.48) for females. The mean scores remained constant across age. A Mann-Whitney U-test confirmed these differences to be significant (ADHD: Z= -10.80, P < 0.001; antisocial behaviour: Z= -77.61, P < 0.001).

Of the 29.1% (552) of mothers who reported smoking during pregnancy, 38.6% (213) smoked 1-10 cigarettes/day, 55.1% (304) smoked 11-20/day and 6.3% (35) smoked more than 20/day. The mean scores for both antisocial behaviour and ADHD increased with the number of cigarettes smoked. Means of 70.11 and 70.09 for antisocial behaviour and ADHD respectively were calculated for the non-smoking category, 0.15 and 0.11 were calculated for those smoking fewer than 10 cigarettes per day. Means were 0.35 and 0.24 for those smoking 11-20/day, and 0.24 and 0.30 for those smoking 20 or more cigarettes per day. Both antisocial behaviour and ADHD correlated significantly with amount of maternal prenatal smoking (antisocial behaviour: r=0.17, P < 0.001; ADHD: r=0.14, P < 0.001).

A gender limitation model was used to identify whether the parameter estimates differed significantly across gender; for ADHD no such difference was found (Δχ=2.823(4), P=0.588), although for antisocial behaviour there was a small but significant difference (Δχ=24.206(4), P < 0.001.) However, as we were not aiming to examine gender differences in these analyses we regressed out both gender and age differences and included males, females and opposite-gender twin pairs in our analyses.

Univariate models

The monozygotic and dizygotic correlations for ADHD were 0.74 and 0.45 respectively, and the respective correlations for antisocial behaviour were 0.68 and 0.44, suggesting a genetic contribution to both. The univariate analyses showed ADHD to be moderately heritable, with both an additive and non-additive genetic component. Neither of these parameters could be dropped from the univariate analysis without significantly reducing the fit of the model. The broad heritability of this phenotype is thus approximately 74%. However, dropping non-additive genetic influences (D) from the antisocial behaviour model did not result in a worse fit, although dropping additive genetic influences (A) did. The AE model is thus the best fit, and the heritability is 66% (Table 1).

Table 1 Univariate ADE models for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and antisocial behaviour

| Phenotype | Model | A (95% CI) | C (95% CI) | D (95% CI) | E (95% CI) | S (95% CI) | χ2 (difference)1 | d.f. (difference)1 | P (difference)1 | AIC (difference)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD2 | ADES4 | 0.37 (0.17-0.57) | [0] | 0.37 (0.17-0.58) | 0.24(0.21-0.26) | 0.02 (0.01-0.03) | 5.988 | 7 | 0.541 | −8.012 |

| ACES | 0.74(0.70-0.77) | 0.00(0.00-0.02) | [0] | 0.25 (0.22-0.28) | 0.02(0.01-0.03) | 20.137 | 7 | 0.005 | 6.137 | |

| AES | 0.74(0.71-0.77) | [0] | [0] | 0.25(0.22-0.28) | 0.02(0.01-0.03) | 20.137(14.149) | 8(1) | 0.010(<0.001) | 4.137(12.149) | |

| DES | [0] | [0] | 0.75(0.72-0.77) | 0.23(0.21-0.26) | 0.02(0.01-0.03) | 18.316(12.328) | 8(1) | 0.020(<0.001) | 4.137(12.149) | |

| CES | [0] | 0.45(0.41-0.48) | [0] | 0.53 (0.50-0.57) | 0.02(0.01-0.03) | 27.751(237.614) | 8(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 241.751 (235.614) | |

| ADE | 0.43(0.22-0.63) | [0] | 0.33(0.13-0.54) | 0.24(0.21-0.26) | [0] | 53.801(47.813) | 8(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 37.801(45.813) | |

| Antisocial | ADES | 0.59(0.40-0.69) | [0] | 0.07(0.00-0.27) | 0.30(0.27-0.34) | 0.03(0.02-0.04) | 8.796 | 7 | 0.268 | −5.204 |

| behaviour3 | ACES | 0.66(0.58-0.70) | 0.00(0.00-0.07) | [0] | 0.31(0.28-0.34) | 0.03(0.02-0.04) | 9.336 | 7 | 0.229 | −4.664 |

| AES4 | 0.66(0.63-0.70) | [0] | [0] | 0.31(0.28-0.34) | 0.03(0.02-0.04) | 9.336(0.540) | 8(1) | 0.315 (0.462) | −6.664(−1.460) | |

| DES | [0] | [0] | 0.68(0.64-0.71) | 0.29(0.26-0.33) | 0.03(0.02-0.04) | 42.180(33.384) | 8(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 26.180(31.384) | |

| CES | [0] | 0.43(0.40-0.47) | [0] | 0.54(0.50-0.57) | 0.03(0.02-0.04) | 138.408(129.068) | 8(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 122.408(127.068) | |

| ADE | 0.68(0.49-0.73) | [0] | 0.01(0.00-0.21) | 0.30(0.27-0.34) | [0] | 89.483(80.687) | 8(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 73.483(78.687) |

Bivariate models

A substantial correlation of 0.62 (P < 0.001) between antisocial behaviour and ADHD was demonstrated, and the results of bivariate model fitting are presented in Table 2. As it was possible to drop additive genetic effects specific to antisocial behaviour, the best fitting Cholesky decomposition model is one in which path a3 was dropped, thus setting the genetic correlation at 1.0. Thus there are no genetic effects specific to antisocial behaviour. Non-shared environment also appears to influence the correlation between the two phenotypes. Moreover, it is not possible to drop the two paths from smoking to antisocial behaviour or ADHD, indicating that smoking is significantly associated with both phenotypes, contributing approximately 2% of the variance for ADHD and 3% for antisocial behaviour.

Table 2 Results of bivariate model fitting

| Model | ADHD | Correlation | ASB | Fit | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | d1 | e1 | s1 | a2 | e2 | a3 | e3 | s2 | χ2 (difference)1 | d.f. (difference)1 | P (difference)1 | AIC (difference)1 | |

| Cholesky | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 22.303 | 20 | 0.324 | −17.697 |

| Drop s1 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.23 | [0] | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 69.515(47.211) | 21(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 27.515(45.211) |

| Drop s2 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.27 | [0] | 101.556(79.252) | 21(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 59.556(77.252) |

| Drop a2 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.55 | 0.02 | [0] | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 505.181(482.877) | 21(1) | <0.001(<0.001) | 463.181(480.877) |

| Drop a3 2 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.663 | 0.04 | [0] | 0.27 | 0.03 | 24.267(1.944) | 21(1) | 0.281 (0.163) | −17.753(−0.056) |

| ADHD mediating | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 0.02 | — | — | 0.58 | 0.42 | [0] | 97.121 | 22 | <0.001 | 53.121 |

Although it is not possible to directly compare the ‘causal’ model with the Cholesky model, the model in which the relationship between maternal prenatal smoking and antisocial behaviour was mediated by ADHD did not fit the observed data, judging by the large and significant χ2 fit, whereas the Cholesky model does appear to satisfactorily explain our data statistically.

DISCUSSION

Causes of covariation

Both ADHD and antisocial behaviour have a substantial genetic and moderate non-shared environmental influence, although there is evidence of both additive and non-additive genetic influences on ADHD and only additive genetic influences on antisocial behaviour. As shown previously in other studies (Reference Silberg, Rutter and MeyerSilberg et al, 1996) and for this data-set using categorical definitions (Reference Thapar, Harrington and McGuffinThapar et al, 2001), additive genetic influences account for most of the covariation between the two, with a non-shared environmental effect also contributing to a small extent.

Contribution of maternal prenatal smoking to the phenotype

Consistent with previous studies, we found that maternal smoking during pregnancy was associated with antisocial behaviour as well as ADHD, contributing 3% to the variance of antisocial behaviour and 2% to the variance of ADHD.

Relationship between maternal prenatal smoking, ADHD and antisocial behaviour

We investigated whether the relationship of maternal prenatal smoking with antisocial behaviour was attributable to the association of maternal smoking in pregnancy and ADHD and the covariation of the two childhood phenotypes. However, the ‘causal’ model did not fit the data at all whereas the Cholesky model did, suggesting that smoking in pregnancy has a specific influence on each, accounting for some of the covariance between them, rather than resulting from this covariance. These findings suggest that the association of smoking in pregnancy with antisocial behaviour is not attributable to its association with ADHD.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, the age range of the twins was large and the sample contained male, female and opposite-gender twins. A larger twin data-set might allow more thorough investigation of the relationships, controlling for differences in both age and gender. However, according to this study and previous research, these differences may not be so important. Second, all measures used in this study were rated by a single individual, with mothers accounting for a large proportion of the raters. Consequently shared rater effects may account for some of the covariance between phenotypes. This is an especially important factor given that maternal prenatal smoking may index antisocial behaviour in the mother (Reference Silberg, Parr and NealeSilberg et al, 2003), which may be associated with reporter bias. Using different raters' accounts of the child's behaviour, such as the child him- or herself, may help to overcome this problem. Finally, the data-set is cross-sectional; the mother's report of her smoking during pregnancy is retrospective and a memory of both smoking and the amount smoked between 5 and 18 years previously was required. Consequently memory recall may have an effect on the outcomes of the study.

Another limitation of this study is that it fails to account for the fact that maternal prenatal smoking may be an index of other latent risk variables transmitted from the mother to the children. For example, it has been suggested that maternal prenatal smoking may index a broader antisocial phenotype in the mother (Reference Silberg, Parr and NealeSilberg et al, 2003). Consequently, antisocial behaviour of the offspring may partly or entirely result from genetic transmission of the propensity to antisocial behaviour from the mother to child (Reference Fergusson, Woodward and HorwoodFergusson et al, 1998; Reference Brennan, Grekin and MednickBrennan et al, 1999). Although it was not possible to test this hypothesis in the present study, lack of a significant contribution of shared environmental influences along with a significant influence of maternal prenatal smoking suggests an underlying genetic rather than environmental mediation, consistent with other studies (Reference Maughan, Taylor and CaspiMaughan et al, 2004). Finally, maternal prenatal smoking may be indicative of other environmental risk factors for antisocial behaviour, such as poor family relationships (Reference van den Bree, Whitmer and Pickworthvan den Bree et al, 2004) and low socio-economic status (Reference Wakschlag, Pickett and CookWakschlag et al, 2002). Longitudinal studies and children of twins studies may be more useful in differentiating these causal relationships.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Maternal prenatal smoking is associated with both antisocial behaviour and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring.

-

▪ The association of smoking in pregnancy with antisocial behaviour in offspring appears to operate independently; it does not appear to be mediated through the covariation with ADHD.

-

▪ We cannot conclude with confidence that smoking during pregnancy is not a direct risk factor for both ADHD symptoms and conduct disorder in offspring. Therefore, the safest clinical message is that smoking in pregnancy should be avoided.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The data-set is cross-sectional, covers a large age range and both males and females.

-

▪ The measures used in this study were all parent-rated, and the majority of raters were the mothers; consequently if smoking behaviour is, as has been suggested, an index of maternal antisocial behaviour, there may be some bias from shared rater effects in the maternal responses.

-

▪ The report of maternal smoking in pregnancy is retrospective. Problems with such long-term memory recall may influence the results.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Medical Research Council scholarship to T.M.M.B.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.