Introduction

Since 2008, there has been a massive expansion of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) within the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme in England (Clark, Reference Clark2018). Its aims were to significantly increase the availability of National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended psychological treatments for mood and anxiety disorders within the NHS. There has been a large training programme of predominantly cognitive and behavioural therapies throughout England. Therapists are grouped together in local services funded by Clinical Commissioning Groups. Some are managed by NHS mental health trusts; others are part of the charity sector; and a few are managed by the private sector. In parallel with these NHS developments, there has also been a gradual increase in CBT provided in the private sector. Some private practitioners work independently, although there is a trend to work together in group practices.

The increase in provision of CBT within both the NHS and the private sector has led to a rise in competition, especially in private services, with branding becoming an increasingly important strategy in social marketing and internet searches. A brand is the way an organisation (or sometimes an individual) chooses to present itself. More than simply a label or name, a brand evokes recognisable emotions and images in members of the public. A brand name is often the vehicle though which individuals first become aware of an organisation, and can therefore be central to managing public perceptions (Rampersad, Reference Rampersad2008) and in the health sector trying to improve population health (Evans and Hastings, Reference Evans and Hastings2008). Businesses often spend considerable time refining their name to encapsulate the values they wish to convey to customers and the emotions they wish to invoke. An example of a well-known brand is ‘Apple’, which might evoke images of simplicity and being different from a PC.

Nonetheless, the process of making informed choices about psychological services is likely to vary drastically from traditional consumer choices, such as that of choosing between Apple products and a PC (Cederberg, Reference Cederberg2017). Yet, the healthcare market has succumbed to the need to adopt marketing strategies similar to those employed in the marketing of traditional goods and services, to ensure financial survival and to promote and produce behaviour change (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Blitstein, Vallone, Post and Nielsen2015; Rendtorff and Mattsson, Reference Rendtorff and Mattsson2009). As a result, personal branding is now commonplace in psychological practice. Historically, marketing of individual psychological services was viewed unfavourably, and the American Psychological Association enforced stringent guidelines relating to advertising and branding (Koocher, Reference Koocher2004). These included restrictions against specialising in multiple areas, offering services to prospective clients beyond the immediate vicinity of their practice, and even the use of bold fonts in advertisements (Koocher, Reference Koocher1994). Concerns were raised that useful consumer information was subsequently being withheld from the public and a gradual loosening of ethical standards for marketing of psychological services followed.

The branding of a service helps to shape the expectations of its consumers (Rampersad, Reference Rampersad2008). However, the findings from Marshall et al.’s (Reference Marshall, Quinn, Child, Shenton, Pooler, Forber and Byng2016) interview study with patients who dropped out of treatment with various IAPT services after one session suggests that these expectations can be unfulfilled. An example is the expectation that group treatments would be interactive and a way to share stories, which was not met. Moreover, one respondent stated that her desire to talk about emotions in treatment contrasted with her practitioner’s expectation for her to engage in homework. This suggests that service users have expectations of what psychological treatment will entail, and when these are not met, it may lead to poor engagement in therapy. As the service name is the first step in the way that a service offering CBT presents itself, it seems likely that this could play a major role in shaping potential service users’ expectations.

Therefore, it is important that brands are easily understood by consumers, although further evidence suggests that public awareness and knowledge about IAPT services is limited, with service users predominantly finding out about IAPT through their GP or other health professionals (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Hicks, Sayers, Faulkner, Larsen, Patterson and Pinfold2011). Informal discussions with clinicians and service users led to the idea for the present study. Whilst considering the names of IAPT services during this discussion, the role of GPs in signposting individuals to IAPT services was raised. It was suggested that there may be a greater need for IAPT services’ branding to be approachable and destigmatising, in comparison with private services, which may be more driven to stand out and be distinguishable from their competitors. The dependency on health professionals’ recommendations poses a significant barrier to referral, as GPs’ knowledge about IAPT services has in the past been identified as lacking (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Hicks, Sayers, Faulkner, Larsen, Patterson and Pinfold2011). However, there is now the expectation that all IAPT services include ‘IAPT’ in either their service name or their subtitle for searches on the internet. Considering these changes to the way psychological services present themselves, and the growing importance of this, the current branding of services offering psychological therapies provides an interesting area for exploration.

Existing research supports the foundational role of branding in the formation of a meaningful therapeutic relationship (Cederberg, Reference Cederberg2017). A brand’s image has the power to shape prospective clients’ expectations about a therapist’s ability to help and understand them, thus informing their consumer decisions. Young people believe service names are influential in considering whether to access a mental health service, after referral (McDevitt et al., Reference McDevitt, McCormack, Murphy, O’Malley and Morrissey2011). Twenty service users attending a newly formed CAMHS team were surveyed regarding their views on a team name. There was a clear preference for non-health and non-illness-related names, with most common themes including safety, nature, help, strength, and inclusion of the word ‘team’ in the title. This is supported by Croydon Talking Therapies’ finding that some clients perceive there still to be a social stigma around mental health issues and felt that it was better for services not to be badged as about mental health (Bedford, Reference Bedford2019). Similarly, an earlier study by Brown and Chambers (Reference Brown and Chambers1986) identified that student interest in counselling centre services differs based on the name of the centre. These studies concluded that private practitioners, mental health clinicians and other mental health service providers must carefully consider the names they have chosen for their practices, as they may impact service utilisation.

Historically, marketing of psychological interventions has been largely unexplored (Rith-Najarian et al., Reference Rith-Najarian, Sun, Chen, Chorpita, Chavira, Mougalian and Gong-Guy2019). A systematic review of health branding showed there is now a wider range of subject areas; however, none of the identified topics were mental health related (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Blitstein, Vallone, Post and Nielsen2015). One of the few studies which has investigated the impact of brand names in healthcare is Odoom et al. (Reference Odoom, Narteh and Odoom2018), who examined the impact of healthcare branding on service users’ intentions to return to the service in the future in two private and two public hospitals in Ghana. They found that while perceived brand image of the clinics played a key role in repeat patronage of the services, there was no significant effect of the brand name on this outcome. However, they were able to find a significant effect of brand name on service users’ perceptions of the clinics. The generalisability of these findings is limited by the focus on a single geographical area and cannot provide conclusions about how brand names shape service users’ perceptions, but ultimately demonstrates that impacts of brand names in healthcare services is an important area to explore. Despite this, to the best of our knowledge, there is currently no research that explores how private and IAPT services offering CBT choose to present themselves to the public.

The aim of our study was therefore to explore the brand names adopted by IAPT and private services offering CBT in England and the way they present themselves. We expected that private services would be more likely to have a brand (because brands are more commonly associated with the private sector, which has to attract and retain clients by directly marketing their services to consumers). Furthermore, we wanted to explore the themes of the words used and whether these differed in the NHS and private sectors. We also reflected on the implications of these service names, from a branding perspective, on service-user perception and awareness.

Method

We compiled the names of all IAPT services and postcodes systematically from the NHS services website (https://www.nhs.uk/service-search/other-services/NHS-psychological-therapies-services-(IAPT)-including-cognitive-behavioural-therapy-(CBT)/LocationSearch/10008). We also compiled the names of private services from the list of accredited CBT practitioners on the CBT Register website maintained by the BABCP (https://www.cbtregisteruk.com). When a therapist had a link to their own website, we identified any service or clinic names that he or she was associated with. We excluded private services from Wales, Scotland and Northen Ireland to provide a direct comparison with IAPT services. For both service types, names were split into either ‘functional’ (where the name served only to indicate the location or professional background of the service, e.g., Barnet IAPT; or for a private service ‘London Psychologist’) or a ‘brand’ name (where words other than description of the location were used to imbue a feeling), e.g., an IAPT service called ‘Let’s Talk’; or a private service called ‘Hello Self’).

We used a chi-squared test to investigate whether the IAPT or private services were more likely to adopt a brand name than a functional name. Where IAPT and private services had a brand name, we extracted the keywords. Different formats or versions of the same root in keywords were combined, (e.g., ‘talk’ and ‘talking’) and an overall frequency was calculated. The list of words that we combined is included in the Supplementary material (Table S1). Two coders independently analysed the keywords extracted, for both IAPT and private services (Supplementary material, Table S2) and classified each as either positive, negative or neutral. The frequency of the keywords extracted from IAPT and private services were compared.

Results

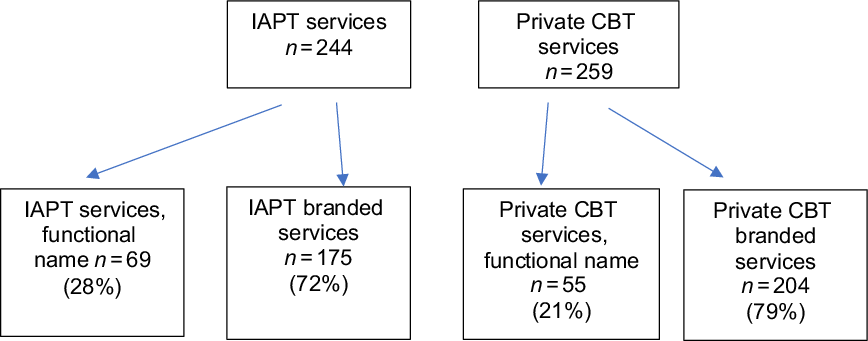

Figure 1 shows the number of functional and brand names; 67% of private services versus 72% of IAPT services adopted a brand name, but this was not statistically significant; χ2 (1, n = 503) = 3.36, p = .07.

Figure 1. A flowchart showing the classification of services as branded or functional.

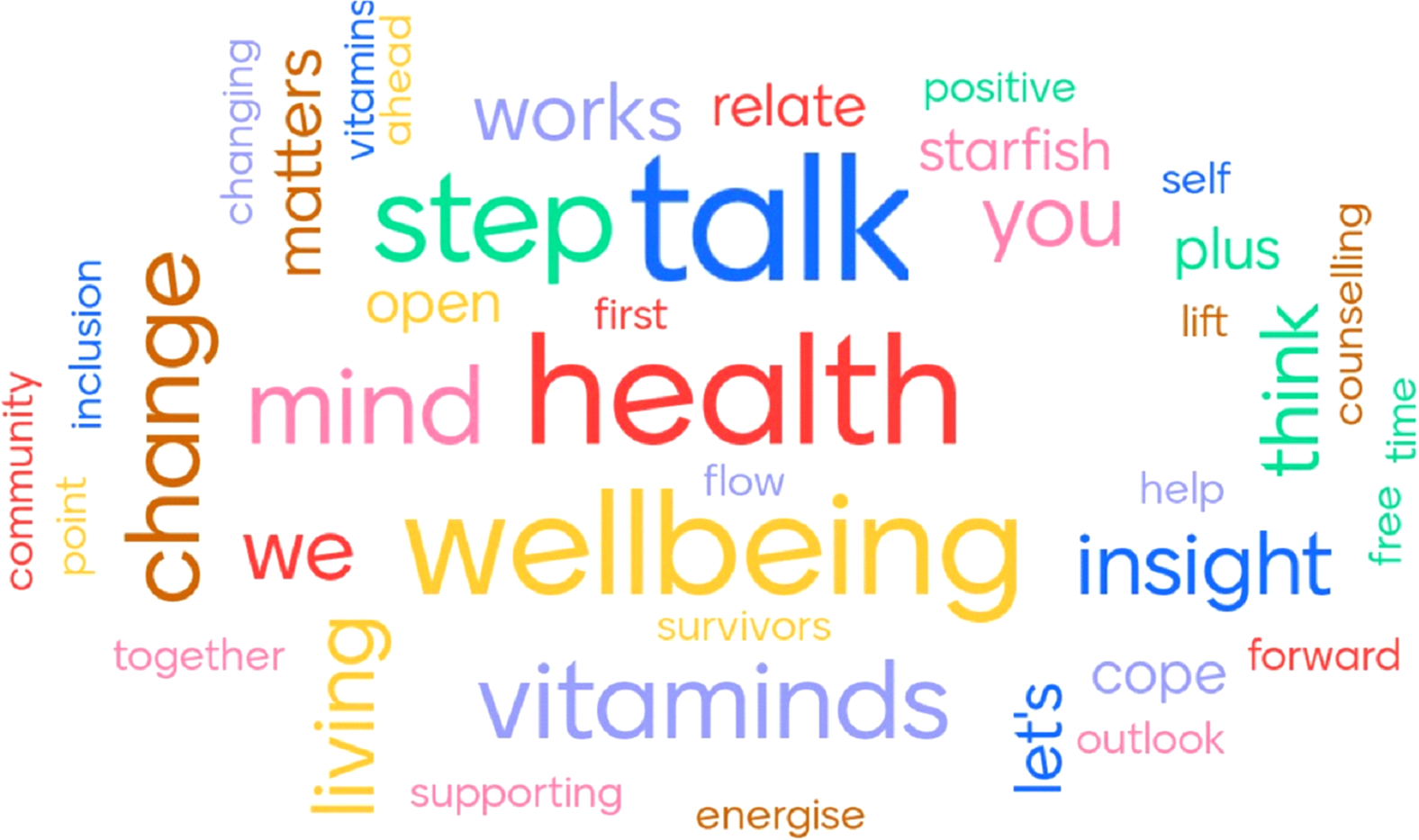

The frequency of each key word was calculated and based on this, two word clouds were created: one for branded IAPT services (Fig. 2) and one for branded private services (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. A word cloud showing key words from branded IAPT services.

Figure 3. A word cloud showing key words from branded private services.

The top five keywords in branded IAPT services were: ‘Talk’ (31.4%, n = 55), ‘Health’ (20%, n = 35), ‘Mind’ (19.4%, n = 34), ‘Wellbeing’ (16%, n = 28) and ‘Step’ (9.7%, n = 17). The top five keywords in the private services were: ‘Therapy’ (32.9%, n = 48), ‘CBT’ (22.5%, n = 46), ‘Counselling’ (8.9%, n = 13), ‘Well’ (8.9%, n = 13), and ‘Mind’ (7.5%, n = 11). Branded private services were more likely to use psychological therapies in their name, such as ‘CBT’, ‘Therapy’ or ‘Counselling’ (n = 107), compared with two branded IAPT services that mentioned ‘Counselling’ and none with ‘CBT’ or ‘Therapy’. Examples of branded IAPT service names ranged from ‘The Talking Shop’ to ‘Wellbeing Matters’ and ‘Back on Track’. Examples of branded names in the private services sample included ‘Restore Control’, ‘Metamorphosis’ and ‘Learning to Play Your Mind’.

Two coders independently analysed 92 keywords extracted, for both IAPT and private services (Supplementary material, Table S2) and classified each as either positive, negative or neutral. These classifications were compared, and the level of agreement was 85.4% with discrepancies between the two raters noted for 12 words: ‘mind’, ‘talk’, ‘change’, ‘relate’, ‘together’, ‘phoenix’, ‘symmetry’, ‘works’, ‘access’, ‘learning’ and ‘precious’ were initially rated as both neutral and positive, whereas ‘survivors’ was rated as both negative and positive. Agreement was ultimately reached through a discussion between the raters. This procedure was repeated for the words classified under each identified theme.

Of the keywords extracted from IAPT services, 25 were rated as positive, 16 were neutral, and none was negative. Comparatively, 33 of the keywords from the private services were rated as positive, 20 were neutral and one was negative. For the frequency of keywords, IAPT services were significantly more likely than private services to contain positive keywords, χ2 (1, n = 481) = 21.91, p<.001.

Thematic analysis

We explored the frequency of words used in the service names (Supplementary material, Table S3) and found that in IAPT the most common key word was ‘talking’ (31.4%) (Supplementary material, Table S5). When combined with ‘think’ and ‘insight’ in 7.5% of services, 38.9% (n = 68) had a ‘cognitive’ theme. This was significantly different from private services, in which only 6.5% (n = 10) of services had a cognitive theme (Supplementary material, Table S4) [χ2 (1, n = 321) = 44.331, p<.001].

Other themes included togetherness and collaboration (n = 31, 17.7%) in the IAPT services (for example ‘Talk Together’ and ‘Inclusion Matters’) with none in the private services, which was significantly different; χ2 (1, n = 321) = 31.726, p<.001.

However, there was a theme of efficacy (n = 22, 15.3%) in the private services, captured in names such as ‘Change Your Life’ and ‘Counselling Works’, which was significantly less in the IAPT services (n = 17, 9.7%); χ2 (1, n = 321) = 3.842, p<.05. The theme of the individual (e.g., ‘self’) was identified in the private services (n = 6, 4.1%) and in the IAPT services (n = 10, 5.7%) but this was not significantly different; χ2 (1, n = 321) = 0.432, p = .511.

Discussion

We analysed the brand names used by both IAPT and private services and found that there was no significant difference between the frequency of IAPT services and private services that had opted to brand themselves. The most common themes in IAPT were ‘talking’ and ‘togetherness and collaboration’, and these were significantly different compared with the private services. A theme of ‘efficacy’ was identified amongst private services, which was also significantly different from IAPT. We also identified that IAPT services often do not give any indication of what the services are and what they provide. In contrast, branded private services were more likely to include a psychological therapy, like CBT, in their name.

IAPT services predominantly offer a range of NICE-recommended therapies for depression and anxiety disorders by CBT (including behavioural activation or behavioural couple therapy), as well as interpersonal psychotherapy, brief psychodynamic therapy and counselling for depression. It is striking that no keywords used in IAPT brands included the words ‘psychotherapy’ or ‘psychological therapies’. Only two of the branded IAPT services included the phrase ‘psychological wellbeing’ in their name, and there was no other mention of ‘psychology’. We also identified 27 services which included the phrase ‘talking therapies’ in their name – it is as if branded IAPT services do not want to be directly associated with a psychological therapy. Instead, many branded IAPT services use euphemisms for psychological therapy such as ‘talking’, ‘thinking’, or ‘insight’. Additionally, there are some very idiosyncratic names, characterised by keywords such as ‘roots’, ‘fly’, ‘freedom’, ‘starfish’, ‘vitaminds’, or ‘energise’.

These branded service names do not convey a relationship based on compassionate coaching or learning of skills. We also found no service which included any reference to ‘doing’ or testing of predictions amongst either the IAPT or private branded services. This is of concern considering that one of the most common therapeutic components offered in IAPT for depression and anxiety disorders are interventions such as activity scheduling (Ekers et al., Reference Ekers, Webster, Van Straten, Cuijpers, Richards and Gilbody2014), behavioural experiments (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Butler, Fennel, Hackmann, Mueller and Westbrook2004) and exposure (Craske et al., Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet2014). Patient expectations of treatment are vital for maintaining motivation and engaging with and adhering to treatments (Sheeran et al., Reference Sheeran, Aubrey and Kellett2007). Nonetheless, the rate of non-attendance in IAPT services is around 47% (Richards and Borglin, Reference Richards and Borglin2011), and one of the factors which seems to contribute to this are patients’ expectations of treatment often not being met (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Quinn, Child, Shenton, Pooler, Forber and Byng2016). It seems possible that no mention of actively ‘doing’ things and the frequency of the ‘talking’ theme (34%) in branded IAPT service names may contribute to these unrealistic expectations of psychological treatment. However, it should be considered that perhaps the reason for the exclusion of a ‘doing’ theme in service names is to allow for the branding to incorporate the other psychological treatments that may be on offer, to which this theme would be irrelevant, such as counselling.

Another emerging theme in branded IAPT services was togetherness and collaboration (17.7%); however, participants in Marshall et al.’s (Reference Marshall, Quinn, Child, Shenton, Pooler, Forber and Byng2016) sample stated there was not much conversation between them and their assessor, and they felt like they were mostly answering questions. Therefore, as outlined in the above findings, there might be a risk of misinterpretation arising from how IAPT services choose to brand themselves. The literature suggests that this may result in poor engagement in therapy which one could hypothesise may lead to poorer treatment outcomes.

By contrast, branded private CBT services use the keyword ‘CBT’ liberally (22.5%). As consumers tend to identify information that is personally relevant to them (Keller, Reference Keller2003), private services may be competing to attract clients, who will use these terms in a search engine. Furthermore, the theme of efficacy identified in private services (15.3%) could be aimed at increasing brand trust, by depicting private services as more solution-focused and efficacious. This is consistent with literature, which highlighted that brands succeed by portraying benefits to consumers (Evans and Hastings, Reference Evans and Hastings2008). On the other hand, terminology such as ‘CBT’ can be off-putting for clients who are unfamiliar with professional acronyms, which could make the service less accessible for some populations, such as older people (Bedford, Reference Bedford2019). Consequently, as branded private services are significantly more likely to portray benefits relevant to service users, such as efficacy, and include treatment-specific terms such as CBT. Future research might analyse service users’ perceptions of private versus IAPT services in terms of perceived effectiveness and accessibility, perhaps through service user focus groups.

The rationale for IAPT and private services choosing these brand names may have been motivated by a wish to be perceived as being approachable. The brand names are overwhelmingly positive and convey the hope of a good outcome. They do not include the experience of difficult emotions, such as sadness and fear during therapy. Mention of other crucial aspects of the process such as courage or the hard work involved are also not included. The emphasis is on the hope of wellbeing, health or change and this is consistent with recovery rates that have been gradually improving to reach 50% (Clark, Reference Clark2018). It is also consistent with the literature that stresses the importance of hope in healthcare (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Bui, Krishen, Homer and LaTour2017). When consumers interact with brands in a self-centred way, where the brand becomes personally relevant, positive or negative moods may be evoked (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2012). These moods can convey information about the brand when consumers try to decide how they feel about the product (Pham and Avnet, Reference Pham and Avnet2004).

Consequently, services may have branded themselves by presenting predominantly positive attributes (such as togetherness, efficacy and talking), with the aim of conveying positive moods to service users and highlighting the potential benefits and hopes associated with treatment. Brands succeed when they describe benefits for their consumers, and often consumers acquire information about a brand with the purpose of obtaining utilitarian benefits (Evans and Hastings, Reference Evans and Hastings2008; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt2012). Hence, the portrayal of difficult emotions and processes may not be effective in branding, as they describe possible perceived disadvantages of treatment: feelings of sadness and fear. This could result in the brand becoming less personally relevant to service users and diminishing feelings of hope. In addition, public health brands are often based on associations individuals hold for healthy behaviours and they must compete with unhealthy social influences (Evans and Hastings, Reference Evans and Hastings2008). Therefore, services may choose to brand themselves positively to portray desired behaviours such as ‘talking’ and reaching out. They may also try to overcome stigma surrounding seeking psychological therapy.

Nonetheless, there is evidence that public awareness of IAPT services is low, and one of the barriers to referral is GPs’ lack of knowledge about IAPT (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Hicks, Sayers, Faulkner, Larsen, Patterson and Pinfold2011). As we identified, branded IAPT services do not clearly state the service that they provide. By also considering that a large majority of IAPT services (72%) choose to brand themselves, it should be considered whether the lack of general awareness about IAPT stems from most services presenting themselves in ways not directly associated with psychological therapies. Furthermore, none of the IAPT services included the name of the problems they predominantly treat in their title, such as mood or anxiety disorders. Bedford (Reference Bedford2019) found that older participants surveyed assumed that Croydon Talking Therapies was a speech therapy service, highlighting the issue with euphemistic service names. One suggested way of increasing general awareness about IAPT is by increasing publicity (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Hicks, Sayers, Faulkner, Larsen, Patterson and Pinfold2011). Despite our findings showing both IAPT and private services tend to brand themselves in positive ways, it is not certain whether this branding effectively reaches and informs service users and other health professionals, nor whether it encourages them to seek or recommend treatment.

Cederberg (Reference Cederberg2017) offers suggestions for carving out a brand for psychological services, starting with intentional reflection on the psychologists’ core values and interests, and being guided from there by previous clinical and academic experiences. Aiming for a brand that highlights qualities that help to distinguish the service from others can prove fruitful. Moreover, ongoing assessment of the image the brand conveys, and a willingness to adapt can help to ensure the branding remains relevant and effective at communicating its purpose to consumers.

In summary, although the majority of private and IAPT services branded themselves, there was no mention of psychological therapies amongst branded IAPT key words. Instead, many branded IAPT services used euphemisms for psychological therapies, such as ‘talking’, ‘insight’ and ‘thinking’. The most predominant theme amongst branded IAPT services was ‘talking’, whilst in branded private services it was ‘efficacy’. Brand names in both private and IAPT settings were overwhelmingly positive. One potential explanation is that positive branding conveys positive moods to service users, and brands are more successful and personally relevant when they portray benefits to the consumer. Nonetheless, we also identified a potential risk of misinterpretation arising from the branding of IAPT services.

Furthermore, although the role of healthcare branding is to communicate with the public, a user-focused evaluation has shown that service users are largely dependent on their GPs recommending IAPT services, whilst GP awareness is low. Further research might involve exploring service users’ perceptions of IAPT and private brand names and how these may impact awareness of the service and perceived effectiveness. Enriching our understanding of the implications of service names and branding will help to ensure that individuals seek treatment where necessary and are not misinformed from the offset about the values and content of the treatment the service provides. While the branding of CBT seems to influence service user expectations of CBT therapists, it is possible that this may have an effect on the practice of CBT therapists and their adherence to treatment protocols – something that is yet to be explored but would prove a worthwhile area of research for the future. This study endeavours to stimulate further research into the impacts of branding choices for mental health services. It is hoped that practitioners will reflect on the implications of the way their service presents itself, by identifying the meanings conveyed to the public so that they can improve treatment uptake. This would be best achieved by service user groups.

Lastly, many hospital wards and hospitals are named after pioneers in their field. However, we found just one private service (‘The Meyer Group Practice’) that evoked the history of CBT, being named after Vic Meyer, one of the founders of the BABCP who developed exposure and response prevention in OCD (Meyer, Reference Meyer1966). Perhaps we will have some Clark and Layard centres in the years to come!

Key practice points

-

(1) Branded services do not always state what they do on the tin, and this may affect expectations of users.

-

(2) The most common keywords were ‘talking’ and ‘thinking’ in IAPT, with no theme of ‘doing’ in IAPT or private services.

-

(3) The brand names are overwhelmingly positive and do not include the experience of difficult emotions, such as sadness and fear during therapy.

-

(4) Consider your service users’ perceptions of service names, to ensure they are not misinformed and can access psychological therapy.

-

(5) Consider using focus groups to advise on the choice and impact from the name of your service.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000349

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This study represents independent research part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethics statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. No ethical approval was required.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, D.V., upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

David Veale: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Resources (equal), Supervision (lead), Validation (lead), Writing-original draft (equal), Writing-review & editing (lead); Chloe Bowles: Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Writing-original draft (equal), Writing-review & editing (equal); Mara Avramescu: Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Writing-original draft (equal), Writing-review & editing (equal).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.