Introduction

Description of DBT

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) is a cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), with emphasis on validation, Zen Buddhist philosophy, a dialectical philosophy and cognitive and behavioural elements of CBT. DBT treats people with emotion regulation difficulties often including self-harming and suicidal behaviours as well as those who meet the criteria for borderline personality disorder (BPD; for a review of the evidence base, see the Cochrane review: Storebø et al., Reference Storebø, Stoffers-Winterling, Völlm, Kongerslev, Mattivi, Jørgensen, Faltinsen, Todorovac, Sales, Callesen, Lieb and Simonsen2020). DBT is a modular therapy consisting of five principle-driven functions: increasing client motivation for change, enhancing of the client’s capability for skilful behaviour, ensuring generalisation of change to the natural environment, assisting client efforts to structure their environment, and enhancing therapist motivation and capacity to deliver the treatment (Linehan, Reference Linehan2015). Comprehensive treatment programmes seek to meet all functions of treatment by providing treatment modes of weekly individual therapy, weekly skills training for clients, access to between-session coaching to promote generalising new behaviours to all relevant areas of a client’s life, as-needed activities to structure the environment, and weekly consultation team meetings for therapists. In line with research that emphasises the importance of skills training (Neacsiu et al., Reference Neacsiu, Rizvi and Linehan2010) when clients are not engaging in suicidal or self-harming behaviour or when non-clinical populations are taught DBT skills, the individual therapy component may be removed. For a review of research on both comprehensive treatment and treatment that emphasised skills acquisition with individual therapy removed, see Hastings et al. (Reference Hastings, Swales, Hughes, Jones and Hastings2022), Lyng et al. (Reference Lyng, Swales, Hastings, Millar, Duffy and Booth2020), and Miga et al. (Reference Miga, Neacsiu, Lungu, Heard, Dimeff and Swales2019).

Like other CBT therapies, the emphasis of the first stage of DBT is on problem-solving and behavioural change as opposed to insight. In contrast to other CBT therapies, DBT is similar to other schools of psychotherapeutic thought in its perspective on the treatment relationship as a vehicle for change (Swales and Heard, Reference Swales and Heard2007). DBT, through its incorporation of a dialectical philosophy, emphasises the interconnection of all things such that clients and therapist are mutually impactful and shaping of the other’s behaviour in each transaction. In addition, dialectical and Zen Buddhist philosophies posit that all things are caused, and that each moment is ‘perfect’ because it is a result of all moments that have come before it. Thus, even though DBT is present focused, the past and learning histories are also incorporated into every interaction.

A fundamental assumption of DBT is that the therapeutic relationship is a ‘real’ relationship in which both parties are subject to the same behavioural principles in the shaping of their interactions. Each party brings their learning history, emotions, cognitions and urges to the therapy. When providing DBT, therapists are also expected to use the tools and strategies of the treatment on themselves to aid the client and themselves. Assistance in the application of DBT to the therapist occurs in the DBT mode of weekly consultation team meetings. Extensive descriptions of the processes of DBT consultation teams can be found in Sayrs (Reference Sayrs and Swales2019) and Sayrs and Linehan (Reference Sayrs and Linehan2019). Linehan (Reference Linehan1993) writes that DBT therapists provide the therapy to themselves/each other in consultation team meetings. In embracing a dialectical philosophy, a reasonable assumption is that a therapist’s personal experience of mental health will impact their behaviour in the present. Many schools of psychotherapy take this perspective regarding a therapist’s experience of mental health issues and seek to ameliorate any issues related to the therapist by requiring trainees to have their own therapy during their training (Adams, Reference Adams2014; Schwartzman and Muir, Reference Schwartzman and Muir2019). DBT, like other CBT therapies, does not require that. Instead DBT emphasises the deliberate practice of DBT through consultation team processes. Deliberate practice work, written about by Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015), can be divided into two schools, one that emphasises the use of the skills of the therapy for the personal benefit and development of the practitioner (e.g. CFT from the inside out) and one that is about helping therapists have the means to practise therapeutic concepts and strategies known to be more complex and difficult to master (e.g. Boritz et al., Reference Boritz, McMain, Vaz and Rousmariere2023). The processes of the consultation team attend to both types of deliberate practice.

The wounded healer

The concept of the ‘wounded healer’, which espouses that therapists simultaneously support clients with recovery processes while at the same time also reaping the benefits of the therapeutic process for their healing, is ubiquitous throughout the literature on therapists as patients (Farber, Reference Farber2017; Miller, Reference Miller1981). There is a growing literature on mental health issues and therapists, with a special issue of the Journal of Clinical Psychology (August 2011) devoted to this topic, for example. Among others, Adame (Reference Adame2011), Adame (Reference Adame2014), Cvetovac and Adame (Reference Cvetovac and Adame2017), Richards et al. (Reference Richards, Holttum and Springham2016), and Gilbert and Stickley (Reference Gilbert and Stickley2012) wrote about complications related to identity when one is both a service user and service provider. Concepts of ‘wounded healer’ and ‘impaired practitioner’ emerge from this literature. A wounded healer’s ability for empathy is heightened by their own experiences, while an impaired practitioner may be vulnerable to re-traumatisation by encounters with clinical material that is similar to their history and may struggle to access appropriate support due to stigma attached to disclosing mental health difficulties (Conchar and Repper, Reference Conchar and Repper2014; Cvetovac and Adame, Reference Cvetovac and Adame2017; Zerubavel and Wright, Reference Zerubavel and Wright2012). Richards et al. (Reference Richards, Holttum and Springham2016) suggest that mental health practitioners with mental health needs may have two separate and unintegrated identities of ‘patient’ and ‘professional’. Goldberg et al. (Reference Goldberg, Hadas-Lidor and Karnieli-Miller2015) describe four stages of development as one proceeds from service user to someone with integrated professional and personal identities. Adame (Reference Adame2011) and Adame (Reference Adame2014) also highlight the shifting nature of identity when one is both service provider and service user. Supervisors are highlighted as important in therapists’ decisions to disclose their own experiences of mental health difficulties and support clinicians to differentiate between their own issues and those of clients (Cleary and Armour, Reference Cleary and Armour2022).

Therapists who work with clients who are chronically suicidal and engaging in self-harming behaviours are known to be at greater risk of burn-out and compassion fatigue, which also may be related to their own mental health vulnerabilities or past histories (Turgoose and Maddox, Reference Turgoose and Maddox2017). Reviewing more generic research on lived experience of mental health issues amongst mental health professionals over a nearly 40-year period, Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Leskela and Hoffman-Konn2016) estimate prevalence rates to be between 50 and 85%, and reported a prevalence rate of 75% in their own empirical work. Those who do disclose these issues to colleagues may be more likely to face the same stigma as their clients do (i.e. Posluns and Gall, Reference Posluns and Gall2020) or they may face workplace stigma (Stuetzle et al., Reference Stuetzle, Brieger, Lust, Ponew, Speerforck and von Peter2023). In order to minimise burn-out and maximise recovery for all, there is a duty of care towards therapists who struggle with mental health difficulties. Beyond that, a greater understanding of the DBT therapists’ side of the transaction could be of use in helping clients.

Mental illness is a stigmatised experience with people facing these difficulties often not disclosing them (i.e. Harris et al., Reference Harris, Leskela and Hoffman-Konn2016; Waugh et al., Reference Waugh, Lethem, Sherring and Henderson2017). Over the last decade, attempts to shift public perception through public health and other education campaigns about people with mental health difficulties have been most impactful among adolescents and less so among adult populations (Waugh et al., Reference Waugh, Lethem, Sherring and Henderson2017). For adults, having continuous contact with adults in similar roles to themselves with known mental health difficulties seems to help shift perception more than education (Waugh et al., Reference Waugh, Lethem, Sherring and Henderson2017). Amongst mental health professionals, there is still much stigma against patients with a diagnosis of BPD or schizophrenia (Valery and Prouteau, Reference Valery and Prouteau2020). While mental health attitudes towards their clients with mental health difficulties have improved some, one study demonstrated that mental health practitioners had more negative attitudes towards colleagues who disclose mental health difficulties (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Leskela and Hoffman-Konn2016). Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Leskela and Hoffman-Konn2016) hypothesised that the stigma experienced by professionals with experiences of mental health difficulties may be related to professional bodies mandating disclosure of mental health difficulties only if there is the possibility of being impaired in professional undertakings. In another study, however, Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Leskela, Lakhan, Usset, DeVries, Mittal and Boyd2019) showed that their two-year intervention, focusing on education and exposure, improved attitudes of mental health professionals towards other mental health professionals with mental health issues.

Laverdière et al. (Reference Laverdière, Kealy, Ogrodniczuk and Morin2018) examined mental health among 240 psychotherapists in Canada, including CBT therapists. Adams’ book, The Myth of the Untroubled Therapist (2014), reviews qualitative interviews about psychotherapists’ personal histories and choices to train in a specific paradigm. Finally, Spence et al. (Reference Spence, Fox, Golding and Daiches2012) posited that self-disclosure of any issues might be more challenging for CBT-oriented therapists as opposed to those with different theoretical orientations due to the ‘therapist as expert stance’ related to the scientific approach. To the best of our knowledge, the only data on the mental health experiences of dialectical behaviour therapists specifically as a subset of cognitive behaviour therapists focuses on burn-out (Allgood, Reference Allgood2022; Jergensen, Reference Jergensen2018; Warlick et al., Reference Warlick, Farmer, Frey, Vigil, Armstrong, Krieshok and Nelson2021).

Current study

The current study seeks to explore the experience of mental health issues among DBT therapists. In constructing this exploratory quantitative research, we predicted that at least 1:6 respondents would endorse a mental health diagnosis based on prevalence rates of mental health diagnoses amongst adults in the UK (Office for National Statistics, n.d.). We also thought broadly about any issue related to the likelihood that someone had experience of mental health difficulties, including the experience of adverse childhood experiences, which are known to lead to mental health difficulties and the experience of stigma in adult life (Purtle et al., Reference Purtle, Nelson and Gollust2022). Adverse childhood experiences are defined as potentially traumatic events in the home or community before the age of 17. Some examples include witnessing violence in the household or community, neglect, abuse, or having a family member engage in suicidal behaviour or substance misuse (see: https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html). Finally, we gathered information about the disclosure of mental health issues and attitudes towards clients with BPD to gain an understanding of DBT therapists’ experience and stigmatising attitudes.

Method

As this topic has not been studied, we employed an exploratory methodology. Quantitative data were collected through a survey that included validated measures and other questions on topics that had a demonstrated correlation with the likelihood of experiencing mental health issues and/or stigma. Anyone who received training through British Isles DBT was contacted via email and alerted to the possibility of participating in this study, which had ethical approval from Bangor University, UK (approval no. 16770/2020). Study participants provided information on their professional background, training experience, attitudes towards clients with BPD, as well as their experiences of ‘mental health difficulties’. Demographic questions were asked about gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and earnings. Unfortunately, due to technological issues, data on ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and earnings were only successfully collected for the final 60 survey respondents.

Respondents were asked various questions related to mental health difficulties: (1) have you ever had mental health concerns?; (2) do you have a formal mental health diagnosis?; and (3) have you ever engaged in any of the following behaviour: (a) self Harming, (b) attempted suicide, (c) substance misuse; (d) eating disordered behaviour, (e) violence towards others, or (f) dissociation. They were also asked about adverse childhood experiences as these are demonstrated to be related to mental health issues in adult life (Merrick et al., Reference Merrick, Ports, Ford, Afifi, Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor2017). Quality of life was measured on the EQ-5D-3L. Questions were also posed about whether they had accessed psychotherapy at any point, taken psychotropic medication, or disclosed mental health difficulties to colleagues or clients, as well as eliciting their perceptions related to accessing help for their mental health concerns. Finally, participants were asked to fill in a questionnaire regarding their attitudes towards clients with BPD. Additionally, anyone who endorsed a formal diagnosis of a mental illness was asked to complete the ISMI-9 and the Stigma Resistance Scale questionnaire.

Measures

Attitudes towards BPD Questionnaire (ABPDQ)

The ABPDQ (Fruzzetti, Reference Fruzzetti2004) assessed stigma towards individuals with a diagnosis of BPD and related problems. The ABPDQ is a 30-item scale, in which each item describes a stigmatising statement towards individuals with BPD (or a non-stigmatising statement in the case of reverse-scored items) and responses are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Thus, scores on this scale range from 30 to 150, with higher scores indicating greater stigma towards individuals with BPD. In this sample, the internal consistency of the subscales, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was .88 at baseline and .90 following training.

Euroquol EQ-5D-3L

The EQ-5D-3L is a generic measure of health and well-being (https://euroqol.org). It asks for ratings in five domains of functioning and is normed to national populations. In the UK, working-age adults score .85 out 1.0 on overall health (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Pickard and Shaw2021).

Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI-9)

The ISMI-9 is a nine-item unidimensional short form of the original English language version of the ISMI-29, which was developed by Boyd et al. (2003) (see Ritsher et al., Reference Ritsher, Otilingam and Grajales2003). Boyd and colleagues published a 10-item short form of the ISMI-29 (see Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Otilingam and DeForge2014). Researchers are encouraged to consider the ISMI-9 and ISMI-10 when designing new studies, as each version may offer certain advantages and limitations (see Hammer and Toland, Reference Hammer and Toland2017). Results of less than 2.0 are considered low to no internalised stigma.

Stigma Resistance Questionnaire (SRS)

The SRS, developed by Firmin et al. (Reference Firmin, Lysaker, McGrew, Minor, Luther and Salyers2017), is a 20-item measure demonstrating a 5-factor structure, reflecting distinct, but related, domains of resisting stigma: (1) self–other differentiation, (2) personal identity, (3) personal cognitions, (4) peer stigma resistance, and (5) public stigma resistance. Internal consistency was adequate for each subscale (.72–.88), and the overall measure (.93). The highest score one could have on this scale is 5.0, indicating complete stigma resistance.

Adverse Childhood Experience Scale (ACES)

Described by many, for example Boullier and Blair (Reference Boullier and Blair2018) and Merrick et al. (Reference Merrick, Ports, Ford, Afifi, Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor2017), the ACES is used to measure adverse childhood experiences, including abuse, neglect, and loss. This is scored on a scale of 0 to 10.

Results

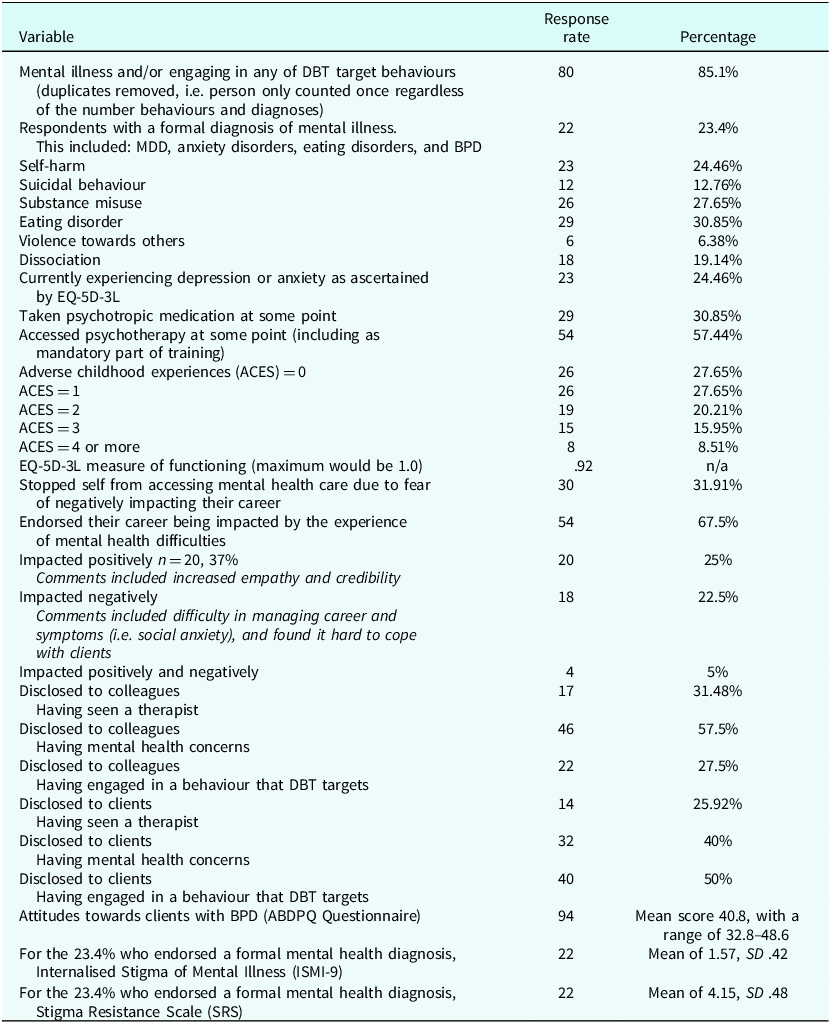

Ninety-four people out of more than 1000 email recipients (a response rate of about 9.4%) responded to the request to participate in a survey on mental health and DBT therapists. Ninety-eight per cent (n=92/94) respondents identified as DBT therapists. Respondents were not asked to specify their definition of ‘practising DBT’; namely they did not specify the functions and modes they provide. Demographic data, displayed in Table 1, is only available for the final 60 respondents due to a technological malfunction. Additionally, only respondents who stated that they have a ‘formal diagnosis of a mental illness’ (n=22/94) were asked to fill in the ISMI-9 and SRS as these questionnaires rely on specific experiences of diagnosis to answer the questions. Survey responses are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1. Sociodemographic data

Table 2. Responses to survey questions

Discussion

Prevalence of mental health difficulties

The results from this survey indicate a relatively high prevalence of mental health difficulties with 85% of respondents endorsing having had mental health concerns. This result matches Harris et al.’s (Reference Harris, Leskela and Hoffman-Konn2016) study of mental health providers that reported n=76/101 (75%) of respondents having experienced mental health difficulties at some point. In terms of a formal diagnosis, 23% of respondents endorsed this experience, which fits the statistics about mental illness in an adult population in the UK (www.mind.org.uk; Mind, UK, n.d.; Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, 2014).

Nearly a quarter of the sample in this research reported having tried to die by suicide, which is much higher than the NHS Digital (2022) estimate of 1:15 people in England attempting to die by suicide in any given year. Respondents in our survey reported both histories of suicidal behaviour as well as a relatively high number of ACES in comparison with the adult population in the UK in which it is reported that approximately 50% of UK adults have experienced one ACE, and 9% experiencing four or more (Bellis et al., Reference Bellis, Lowey, Leckenby, Hughes and Harrison2014). Encounters of ACES by therapists parallel experiences of DBT clients who have often survived invalidating environments (see Grove and Crowell, Reference Grove, Crowell and Swales2019; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019). Despite the relatively frequent experience of ACES of our survey respondents, they also reported relatively high quality of life as measured by the EQ-L5-3D. High quality of life scores may be related to this sample’s high affiliation with socially dominant groups (i.e. ethnicity, socioeconomic and sexual identity). However, the high average obfuscates the experience of a quarter of respondents who endorsed experiencing moderate symptoms of depression and anxiety at the time of data collection (EQ-5D-3L).

Stigma and comparisons with other research

The results of the disclosure of mental health difficulties in this study are different from the ones that Boyd et al. (Reference Boyd, Zeiss, Reddy and Skinner2016) found. In their study of 77 mental health professionals working for the Veterans Administration in the USA, only 16% disclosed their difficulties to colleagues, while 66% disclosed to clients. In our study, 58% disclosed mental health difficulties to their colleagues, but only 28% disclosed having engaged in behaviours treated by DBT to colleagues; 40% disclosed having had mental health concerns to clients and 50% disclosed having engaged in behaviours treated in DBT to clients. More research into the phenomena that facilitated or hindered disclosure within a DBT context would be helpful. It is possible that participation in weekly consultation team meetings, which is a meeting that explicitly applies DBT with all its assumptions and strategies to the therapist, impacts therapists’ decisions about disclosure. The consultation team agreements may also enable more disclosure. With respect to DBT therapists’ disclosure of their own experiences to clients, future research might investigate the influence of the DBT stance of equality in the therapeutic relationship and the emphasis on normalising and self-disclosure on decisions to share experiences.

For the current sample, of particular concern are the 28% of respondents who reported that they stopped themselves from accessing mental health services due to concern for their careers. Further investigation into the experience of workplace stigma, which is defined as the experience of rejection or discrimination in the workplace due to mental health issues, would be helpful. Workplace discrimination on this basis is also known to exacerbate the risk of further mental health crises. Stuetzle et al.’s (Reference Stuetzle, Brieger, Lust, Ponew, Speerforck and von Peter2023) study of 182 mental health professionals with experience of mental health crises concluded that internalised stigma amongst professionals was positively correlated with perceived workplace stigma. The impact of professional regulating bodies’ obligations that require disclosure of their difficulties only if their practice will be impaired could be further examined, as could the role of the supervisor or line manager (Cleary and Armour, Reference Cleary and Armour2022; Spence et al., Reference Spence, Fox, Golding and Daiches2012; Waugh et al., Reference Waugh, Lethem, Sherring and Henderson2017).

Implications

Responses regarding ACES, fears about accessing mental health services and history of mental health difficulties, might also indicate that consultation teams could also focus more specifically on assessing and managing risk issues and the emotional coping of consultation members. A dialectical philosophy, which holds that all things are interconnected, suggests that there could be more space for therapists to explicitly talk about their experiences as ‘wounded healers’. At a minimum, more research into the different ways in which consultation teams manage, discourage or encourage team members to discuss their own difficulties would be helpful. The suicide of a team member would have devastating effects on the team and clients alike. The NHS has a duty of care to both the patients that it treats and its staff. Any data on this could potentially help inform the work of DBT team leaders in their role as caretakers of their teams. One would also wish to exercise caution with how the question was asked and what was done with the data. Simply asking the question about a history of suicidal behaviour without a comprehensive assessment of ongoing risk, indiscriminate data collection could exacerbate workforce stigma issues and undermine the recovery aspects and increased quality of life associated with employment.

Additionally, further research on DBT therapists’ use of DBT skills in their own lives may provide information about how DBT therapists cope with their experiences of mental health difficulties. Use of DBT skills is known to be a protective factor against burn-out amongst DBT therapists (Jergensen, Reference Jergensen2018; Warlick et al., Reference Warlick, Farmer, Frey, Vigil, Armstrong, Krieshok and Nelson2021). Further research on this subject amongst DBT therapists could also support efforts to integrate skills on stigma management into the DBT curriculum (Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Mirabito, Kirkman and Shaw2021) and to incorporate educational pilot programme aims (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Leskela, Lakhan, Usset, DeVries, Mittal and Boyd2019). Research on skills use and the processes of the consultation team that explicitly apply DBT to the therapist in aid of their client work, including potentially managing their own experience of mental health difficulties, would add to the body of research on the self-practice/self-reflection and on the bridging of personal and professional identities.

Limitations

It is also possible that the high rate of people in this sample reporting the experience of mental health issues may be related to sampling bias. It is probable that people who have an interest in mental health in psychotherapists due to their own experiences would be more likely to respond to a voluntary survey. Additionally, respondents to this survey were predominantly white, cis-gendered, heterosexual females, which forms the dominant group of the psychotherapy community in the UK. This status may have facilitated disclosure of mental health issues, whereas people from minority backgrounds within the psychotherapy community may be reluctant to come forward with their experiences due to intersectionality issues. The demographics of the population may also explain the very high quality of life scores. A drawback of this study was also that participants were not asked to report the age at which they engaged in suicidal or other DBT target behaviours. Suicidal behaviour may have been decades earlier and in the ensuing period there was an incorporation of significant other coping skills. Finally, the anonymity and voluntary nature of research participation yielded biased results. If people were required to disclose this information for employment reasons, for example, the responses could be very different.

Finally, the recruiting process was an open one that allowed people to affiliate as DBT therapists without asking them to describe the functions and modes of treatment they are providing. Therefore, it is not clear whether the respondents were providing comprehensive DBT and/or attending weekly consultation team meetings at a minimum. Relatedly, questions about the disclosure of difficulties in the consultation team and the use of the consultation team to manage arising difficulties were not posed.

Future directions

Future research might examine the factors related to DBT therapists with mental health concerns making use of the DBT consultation team as a source of support. Research could also systematically and explicitly examine the impact of perceptions of stigma related to professional organisation requirements of disclosure of mental health issues only if a practitioner is deemed to be impaired by such experiences. In addition, another area of research could focus on the experience of therapist disclosure of difficulties from the perspective of client. Finally, research could examine DBT therapist’s own use of emerging DBT skills for managing stigma.

Key practice points

-

(1) DBT consultation teams and supervisors have a duty of care and may benefit from discussions with DBT therapists about their functioning that goes beyond the current emphasis on burn-out.

-

(2) DBT therapists who recover mental health difficulties may be able to more explicitly teach about their paths as a way of further enhancing the real relationship between DBT therapist and client that is espoused in the assumptions about the treatment.

Data availability statement

Data are available on request to: a.essletzbichler@bangor.ac.uk.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Amy Essletzbichler: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Rebecca Sharp: Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Michaela Swales: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead).

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

Both Amy Gaglia Essletzbichler and Michaela Swales earn money by training therapists in DBT for biDBT.

Ethical standards

Authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS and research has conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Study participants accessed and provided consent to engage through Survey Monkey prior to accessing the questionnaires. The study received ethical approval from Bangor University, UK (approval no. 16770/2020).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.