The passing in June 2020 of dance scholar, cultural historian, and critic Sally Banes marks the loss of one of the ignitors of a renewed understanding of dance studies that took place in the United States throughout the 1980s. Indeed, Banes was undoubtedly one of the pioneers in creating a new way of writing and of thinking about dance. Her approach—mixing an unparalleled eye for movement detail, a love for immersive and patient archival research, and an openness to theoretical analysis — has influenced generations of dance scholars since the publication of her groundbreaking and influential Terpsichore in Sneakers: Post-Modern Dance, which she wrote between 1973 and 1978 and published in 1980. Terpsichore was the first in-depth, scholarly, and comprehensive account of the experiments by the extraordinary cohort of dancers and choreographers who collectively redefined the possibilities for dance as an artform in the early 1960s, the founders of what became known as the New York “downtown” dance scene: Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Judith Dunn, Robert Dunn, Deborah Hay, Fred Herko, Steve Paxton, and Yvonne Rainer, to mention a few. As a testimony to Banes’s extraordinary intellectual energy and sheer passion for her subject matter, the writing of Terpsichore in Sneakers paralleled Banes’s doctoral work under the direction of Michael Kirby in the Department of Performance Studies at New York University. Banes defended her dissertation the same year that Terpsichore in Sneakers was published. And her dissertation was published in 1983 as yet another fundamental book on the same group of choreographers: Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theater, 1962-1964.

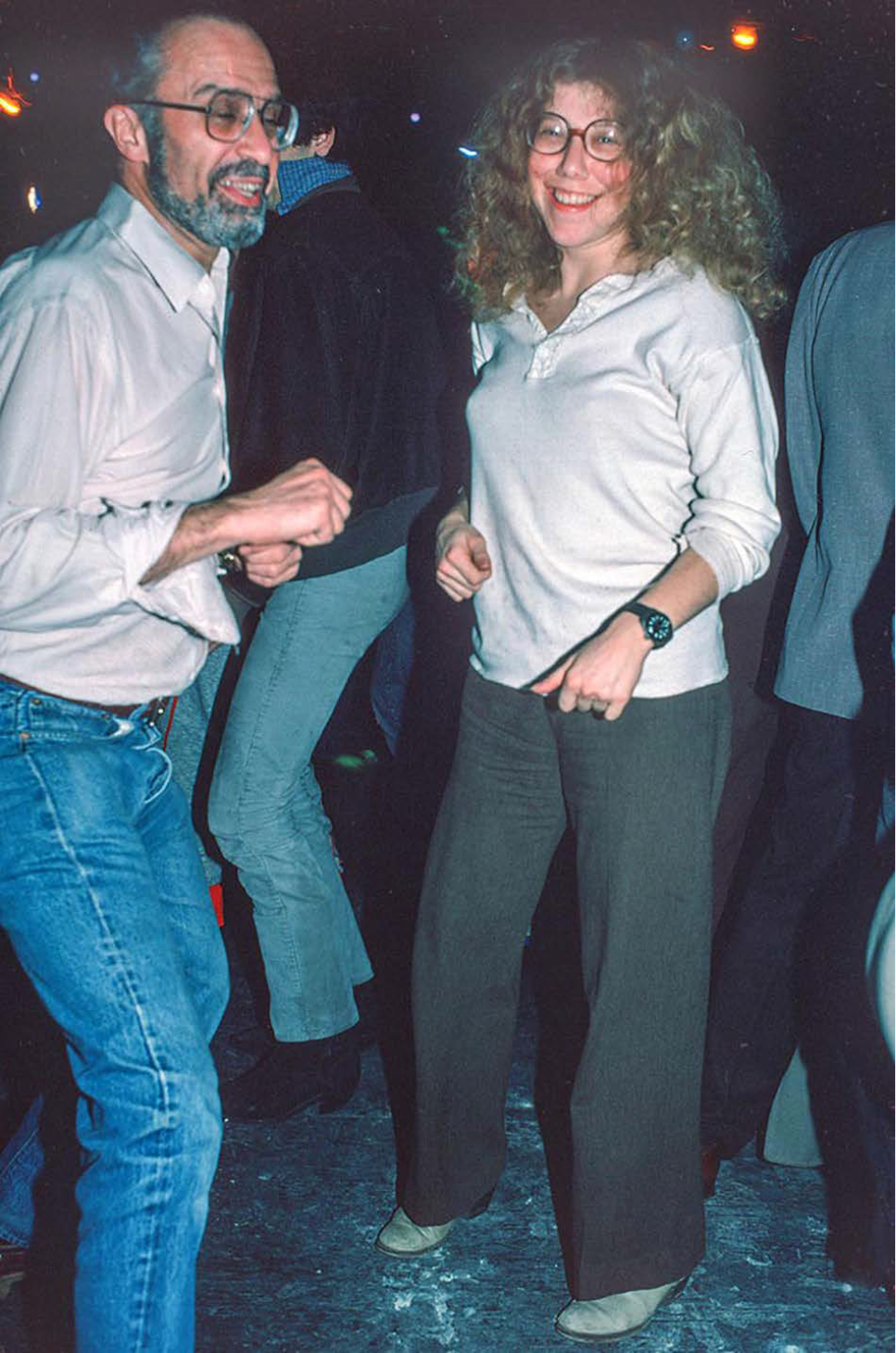

Figure 1 Sally Banes dancing with Tony Silver, director of Style Wars, circa 1982. (Photo by Martha Cooper)

One expects books in dance studies to illuminate—culturally, aesthetically, historically, politically — the works they analyze and present to their readers. But, once in a while, some truly extraordinary dance books achieve something else: their analyses are so acute, the choice of materials so to the point, their insights so compelling and novel, that they become true revelations. They compellingly reveal for the first time the forces (historical, imaginative, political, affective) that shape what was apparently merely moving before our eyes. Those few groundbreaking books do not offer just well-articulated readings of dance and movement; they also help initiate new (dance) movements. For me, Terpsichore in Sneakers falls in this category — along with Susan Leigh Foster’s Reading Dancing (1986); Randy Martin’s Critical Moves (1998); and Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance (1996): all books that, by analyzing movement and dance, actually create the possibility of inventing more and new movements and dances.

I know for a fact that Terpsichore in Sneakers certainly did occasion new motions, even if those new motions I can give an account of happened in the improbable and definitely non-American context of Portugal in the 1980s. It was then and there that I first encountered Banes’s Terpsichore in Sneakers, sometime in 1985 or 1986, when I was still living in Lisbon, just starting to become really involved in experimental dance (but not really interested yet in dance studies). It was my good friend Vera Mantero—at the time a dancer with the Gulbenkian Ballet and about to start her career as a choreographer—who one day showed me a copy of Banes’s book. She’d borrowed it from a friend who had managed to somehow import it from the US. That one copy was a kind of treasure in those days. It most likely was one of the very few copies (if not the only copy) in the country. It circulated from hand to hand amongst the small experimental dance community in Lisbon. Reading its chapters, each organized around a specific choreographer (except the last chapter, which addresses the collective Grand Union), was to plunge into the unfolding of how new ideas for dance can be thematized in the context of their emergence. Banes’s scholarly approach was to carefully listen to the artists, balance what they had to say by also directly invoking contemporary reviewers of those artists’ works, frame it within a general context of collective concerns (not only Judson, but also the larger artistic communities thriving in the West Village throughout the 1960s and early 1970s), and then, as a kind of a gift to the dancers reading her book, end each chapter with a short score or manifesto by the artist she had just discussed. That one copy of Terpsichore in Sneakers, scuttled from hand to hand in 1980s Lisbon, became a portal and a passport and a motor for some young dancers and choreographers looking for another way of conceiving choreography — and its circulation helped generate the momentum behind a movement of migration from Lisbon-based dancers away from the previous major dance-magnets such as Paris, London, or Brussels and direct them to New York City. The link became so strong that, by the early 1990s, a dance festival was created called “Lisbon-NY-Lisbon.” This turn to the New York downtown dance scene in the 1980s and early 1990s was not just a Portuguese phenomenon. I remember hearing a talk by the French dance theorist Christophe Wavelet in the late 2000s, where he mentioned that, for the same generation of French choreographers starting to present work in the early 1990s (Jérôme Bel, Boris Charmatz, Xavier Le Roy), the Judson dancers were an intriguing and important inspiration. It is hard to imagine how they would have accessed these works without a significant engagement with Banes’s books.

Since I was not and am not a dancer, Banes’s Terpsichore impacted me at a different level at the time. The book made me realize the fundamental importance of producing discourse as a partner for any dance making. I believe it is possible to say that, despite the huge impact that Judson Dance Theater and the choreographers associated with it had on the overall artistic scene of which they were a part, their historical importance, their consolidation as a movement, became truly established through Banes’s books. Terpsichore in Sneakers and Democracy’s Body discursively created a new canon for dance. They laid the ground for the subsequent acceptance and consolidation of that canon by the broader community of performance studies scholars, historians of 20th-century art, and curators and artists working in the visual arts. That canon was further expanded in Banes’s important 1993 Greenwich Village 1963, in which she turned her historical and critical eye beyond Judson to look at the broader downtown New York art scene (visual arts, happenings, film, spoken word, music, etc.) as the epicenter of an alternative political and aesthetic history of the 1960s in the US.

Banes’s approach to dances and performances that had been performed sometimes decades prior to each book’s publication demonstrated also how intimate and complex are the relationships between the supposedly neutral and objective dance critic, and the supposedly passionate and engaged artist. Whoever reads Banes’s books cannot help but admire the way she mixes contemporary descriptions and reviews of works along with post-facto interviews, analysis of photographs, original scores or scripts, her own interpretation of those scores and interviews, and her impressions of seeing some of the performances live. All sutured by the clean line of her prose and transparent reasoning. The end result is an ongoing accumulation of precise information drawn from primary source materials, retrospective reflections on the dances by their makers, contemporary assessments by dance reviewers, and critical and historical analysis from Banes. Because Banes reveals all of these voices and perspectives with a sharp style that does not hide collage as perhaps the only ethical historiographic method, her reader cannot help but realize the constructed nature of any historical narrative. And, thus, Banes’s books offer the means by which the historical narrative they present is ready to be undone, critiqued, modified, and rewritten. I cannot think of a more generous act on the part of a scholar.

Banes’s indefatigable and clear-eyed scholarship did not confine itself to dance. With the interdisciplinarity vein that was so characteristic of her work, she also looked for the inordinate and the counterintuitive in live performance. I had the honor to coedit with Banes one of her last books, The Senses in Performance, conceived and initiated a year before her debilitating stroke in 2002. I had just met her in person for the first time, on a panel on the sensorial in performance at ASTR’s November 2000 conference. My presentation focused on the sense of smell in performance, something Banes was also interested in at the time. After the panel was over, and to my utter surprise, all of a sudden she asked: “I am putting together an anthology on the senses in performance. Would you like to be coeditor?” Of course, I said “Yes!” We worked on the volume together for a few months, commissioning and gathering the contributions and starting a preliminary organization of the volume for peer review. Then her tragic stroke happened, and the whole process came to a halt. Once news of Banes’s illness reached our editors at Routledge, they immediately sent me an email stating that they would carry on with the publication, for Sally. True to her trailblazing spirit, Banes’s contribution is a highly original essay on “Olfactory Performance.” It remains one of my favorite performance studies essays.

Terpsichore in Sneakers is also responsible for introducing into the vernacular of art history the expression “postmodern dance.” And, if there was ever an epic clash deriving from Banes’s scholarship, it took place on the pages of this very journal, in a series of vivid exchanges between Banes and Susan Manning, after Manning’s review of the second edition of Terpsichore in Sneakers (see “Modernist Dogma and Post-Modern Rhetoric: A Response to Sally Banes’ ‘Terpsichore in Sneakers’” [TDR 32:4, 1988] and “Terpsichore in Combat Boots” [TDR 33:1, 1989]). In her review, Manning argued that Banes’s use of the term “post-modern” to describe the Judson dances was equivocated and that these works fall more clearly into a “modernist” aesthetics. As examples of true postmodern experiments in US dance, Manning invoked Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, Karole Armitage and Molissa Fenley. I believe that Manning’s argument is thoroughly compelling and her assessment correct. What remains interesting, however, and quite revealing of Banes’s sensitivity and method, is Banes’s reply to Manning: Banes would stick to the term “post-modern dance” to describe the Judson dances, because that was the expression Banes heard being used by the Judson choreographers to describe their own work at the time: “Terpsichore in Sneakers used ‘post-modern’ as a term of historical style that was keyed to the movement that uses it,” Banes wrote in her reply (1989:14). Again, we find Banes’s ethical imperative as a cultural historian: to first of all listen to what artists have to say, to how they themselves describe what they do.

Sally Banes will remain for performance studies and dance studies an example of a scholar who respected deeply—which means critically as well as affectively— the art and the artists who inspired her, and their spirit; while always making sure that her readers remained aware that, through art, what also reverberates is the spirit of an era.