No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 July 2016

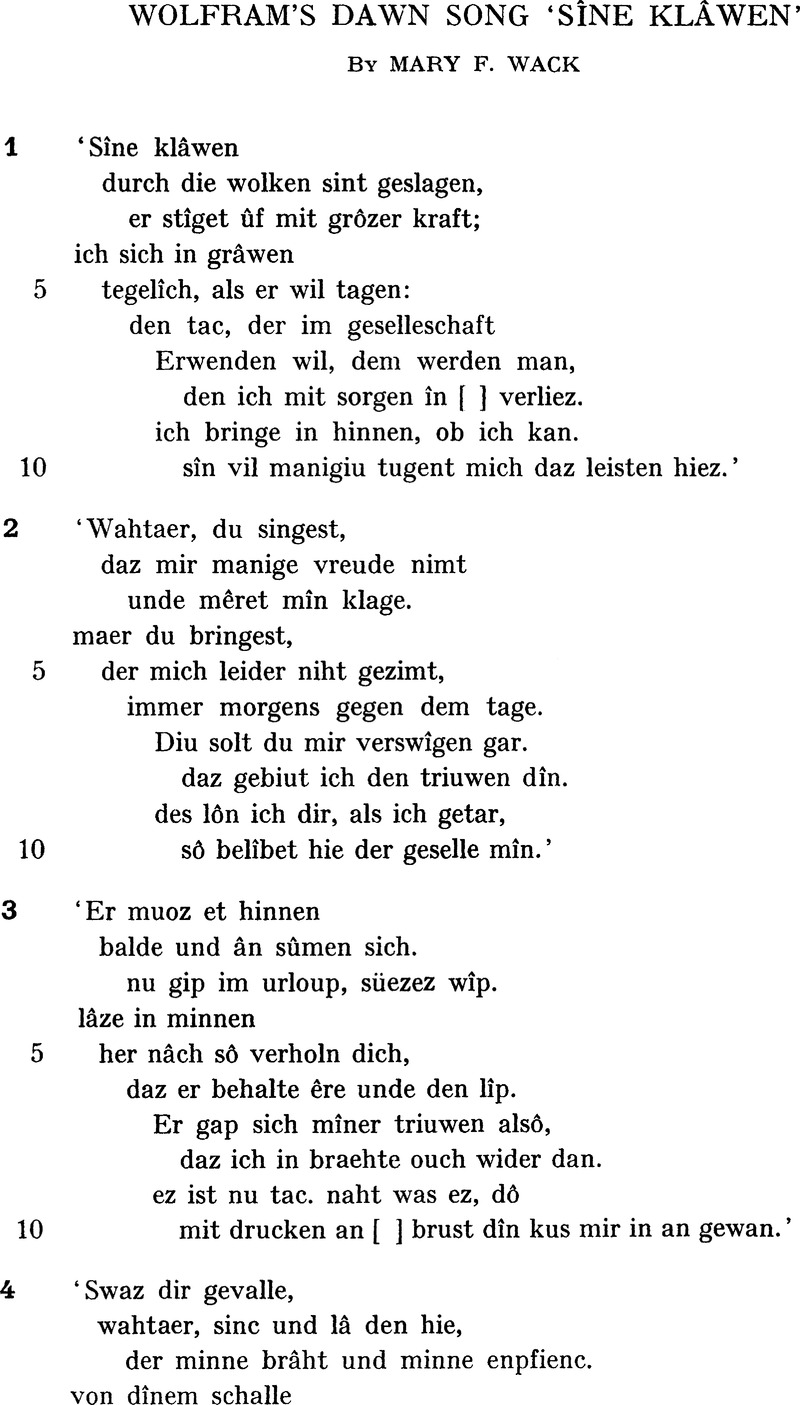

1 The text of the poem is from H. Moser and H. Tervooren, Des Minnesangs Frühling (Stuttgart 1977). A shorter version of this paper was presented at the Convention of the Northeast Modern Language Association, April 14–16, 1983, in Erie, Pennsylvania. I would like to thank Professor Arthur Groos of Cornell University for his reading of earlier drafts of this work.Google Scholar

2 An Arabic parallel of a Morgenlöwe was adduced by F. R. Schröder, 'Der Minnesang I,’ Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift 21 (1933) 179; A. T. Hatto compares the animal to a falcon or eagle in Eos: An Enquiry into the Theme of Lovers' Meetings and Partings at Dawn in Poetry (The Hague 1965) 785; Jonathan Saville, The Medieval Erotic Alba (New York 1972) 58, proposes an eagle, supported by a single citation from a Middle English versified bestiary; L. P. Johnson, 'Sine klawen,’ in Approaches to Wolfram von Eschenbach, edd. D. H. Green and L. P. Johnson (Bern 1978) 298–99, suggests dragons or griffons while maintaining that 'it would be unprofitable to argue about the precise nature of the monster Wolfram conjures up.’ Most recently Alois Wolf, Variation und Integration: Beobachtungen zu hochmittelalterlichen Tageliedern (Darmstadt 1979) 132, has suggested a lion or eagle which may be a figura Christi, without explaining how it would function in the poem overall. Google Scholar

3 Wolf, , Variation 125–26, voices concern over an anachronistic preoccupation with symbolism, while Peter Wapnewski, Die Lyrik Wolframs von Eschenbach (Munich 1972) 104, comments on the futility of seeking a specific animal for a general principle of opposition to night and love embodied by the creature.Google Scholar

4 The Tagesungeheuer tends to overshadow the watchman in commentaries on this image, causing him to disappear as a ‘character’ or human role in the poem. See H. De Boor, Geschichte der deutschen Literatur (Munich 1953) II 330, and Wolfgang Mohr, 'Wolframs Tagelieder,’ Festschrift für Paul Kluckhohn und Hermann Schneider (Tübingen 1948) 156. Irmengard Rauch, 'Wolfram's Dawn-Song Series: An Explication,’ Monatshefte 55 (1963) 367–74, develops Mohr's point that the watchman ‘is’ the conscience of the lady. Google Scholar

5 Johnson, , 'Sine klawen' 299, mentions the griffon's reputation for vigilance but does not develop this point in his reading of the poem. For a recent summary of griffon lore in the Middle Ages, see Claude Lecouteux, Les monstres dans la littérature allemande du moyen age (Göppinger Arbeiten zur Germanistik 330 I; Göppingen 1982).Google Scholar

6 ed. Lachmann, Karl (6th ed.; Berlin 1926).Google Scholar

7 ed. Leitzmann, Albert (Tübingen 1963).Google Scholar

8 Frauendienst, ed. Bechstein, Reinhold (Leipzig 1888). A valuable discussion of griffons in Middle High German literature is contained in Karl Bartsch's introduction to his edition of Herzog Ernst (Vienna 1869) cxxxii-clx. See also Seifrits Alexander, ed. Gereke, Paul (Deutsche Texte des Mittelalters 36; Berlin 1932) 6143–48. Alexander's griffon ride was depicted frequently in medieval art: R. S. Loomis, 'Alexander the Great's Celestial Journey,’ Burlington Magazine 32 (1918) 136–40 and 177–85.Google Scholar

9 In a poem by Burkart of Hohenfels, the griffon's claws are symbolic of its legendary strength: 'diu bant hant die kraft gewunnen / daz siu bræche niht des grifen kla,’ Minnesang des 13. Jahrhunderts, ed. Kuhn, H. (Tübingen 1962) IX 3.9–10. Other examples include Ulrich von Türheim, Rennewart, ed. Hübner, Alfred (Deutsche Texte des Mittelalters 39; Berlin 1938) 30863; Wirnt von Gravenberg, Wigalois, ed. Kapteyn, J. M. N. (Bonn 1926) 5066–67 and 6317–18; Die Pilgerfahrt des träumenden Mönchs, ed. Bömer, Aloys (Deutsche Texte des Mittelalters 25; Berlin 1925) 9135 and 9508ff.Google Scholar

10 ed. Derolez, Albert (Ghent 1968) fol. 58 v.Google Scholar

11 Millar, Eric G., English Illuminated Manuscripts from the Xth to the XIIIth Century (Paris 1926) illus. 58. The manuscript in question is Brit. Lib. Ashmole 1511, fol. 15 a.Google Scholar

12 Edd. Green, Rosalie et al. (Studies of the Warburg Institute 36; London 1979) II fol. 8 r. Lecouteux, Monstres II 213–18, provides a number of illustrations of the griffon in which the claws can be seen.Google Scholar

13

ed.

Scholfield, A. F. (Cambridge, Mass. 1958) 241: ![]() .Google Scholar

.Google Scholar

14 5.52, ed. Boese, H. (Berlin 1973 ). Bartholomaeus, De proprietatibus rerum 18.54, remarks: ‘Tarn magnos habent ungues & tarn amplos, quod inde fiunt scyphi, qui mensis Regum apponuntur’ (Frankfurt 1601; rpt. Frankfurt 1964). See also Albertus Magnus, De animalibus 23.1, ed. Borgnet, A. (Paris 1891) XII 491.Google Scholar

15 See notes 6 and 7 above. Google Scholar

16 Philostratus, , The Life of Apollonius of Tyana 3.48, reports that the griffon will attack lions and even get the better of dragons and elephants; ed. Conybeare, F. C. (New York 1922 ). See also Isidore, Etymologiae, ed. Lindsay, W. M. (Oxford 1911) 12.2.17; Thomas of Cantimpré, Liber de natura rerum, 5.52; Konrad von Megenburg, Das Buch der Natur, ed. Pfeiffer, F. (Stuttgart 1861) 190; Jacob von Maerlant, Naturen Bloeme, ed. Verwijs, Eelco (Groningen 1878) 1734–36; Sir John Mandevilles Reisebeschreibung in deutscher Übersetzung von Michel Velser, ed. John Morrall, Eric (Deutsche Texte des Mittelalters 66; Berlin 1974) 153; and Der mitteldeutsche Marco Polo, ed. von Tscharner, Horst (Deutsche Texte des Mittelalters 40; Berlin 1935) 69. For the bestiary tradition, see Florence McGulloch, Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries (rev. ed.; Chapel Hill 1962) 123.Google Scholar

17 The Latin is from Bartholomaeus 18.54. Cf. Albertus Magnus, De animalibus 23.1 (Borgnet XII 491) and the vernacular translation Thierbuch Alberti Magni (Frankfurt 1545) Bk. 2. The griffon's antagonism toward men is noted by, among others, Isidore, Bartholomaeus, Thomas of Cantimpré, Hugh of Folieto, De bestiis et aliis rebus 3.4 (PL 177.84), and Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum naturale 16.90 (Douai 1624; Graz 1926). Google Scholar

18 Ed. Bartsch 4204–4334. Google Scholar

19 ed. Bartsch, K., rev. K. Stackmann (5th ed.; Wiesbaden 1965). Cf. also 55.1: ‘Ez was ein wilder grife, der kam dar geflogen’ and 56.2: 'Starc was er genuoc.’ Cf. the illustration in Lecouteux, Les monstres II 215.Google Scholar

20 See note 8 above. Google Scholar

21 Van den Broek, R., The Myth of the Phoenix According to Classical and Early Christian Traditions (Leiden 1972) 272–77 and 303–4.Google Scholar

22 Sbordone, F., Physiologus (Rome 1936) prints the text 182–83. According to Josef Strzygowski, Der Bilderkreis des griechischen Physiologus (Byzantinisches Archiv 2; Leipzig 1899) 107, the cycle of illustrations in this redaction of the Greek Physiologus is close to the Western tradition. On Wolfram's knowledge of Physiologus traditions, see Peter Wapnewski, Wolframs Parzival: Studien zur Religiosität und Form (Heidelberg 1955) 59–62.Google Scholar

23 Sbordone 182—83:’ J. B. Pitra, Spicilegium Solesmense (Paris 1855; rpt. Graz 1963) III 369, prints a similar Greek Physiologus text from a 13th-c. MS (Paris BN 2027).Google Scholar

24 One of the texts is an astronomical treatise published in Catalogus codicum astrologorum graecorum 12, Codices rossicos, ed. Sangin, M. A. F. (Brussels 1836) VI 107. The same motif is contained in the late thirteenth-century Disputatio Panagiotae cum Azymita: see Van den Broek, Myth 274–76.Google Scholar

26 III 48, ed. Conybeare, F. C. (Cambridge, Mass. 1948).Google Scholar

26 M. Valerii Probi in Vergilii Bucolica et Georgica commentarius, ed. Keil, H. (Halle 1848) 24.Google Scholar

27 In Vergilii carmina commentarii, edd. Georg Thilo and Hermann Hagen (Leipzig 1887) III 1.96.Google Scholar

28 Thilo-Hagen, , III 1.62. Ingeborg Wegner, Studien zur Ikonographie des Greifen im Mittelalter (Diss. Leipzig 1928) 15 discusses a representation of a griffon on the ninth-century Areobindus Diptych which resembles the form of griffons as symbols of Apollo on Graeco-Roman sarcophagi. Piero Valeriano Bolzani, Hieroglyphica (Frankfurt 1613) 279, records that griffons 'Apollinem indicabant, veteresque eos Apollineo curru succedere finxerunt … Et in Gallieni numis Gryphes cusos inspicias, cum inscriptione apollini cons. aug.’Google Scholar

29 Scriptores rerum mythicarum Latini tres, ed. Heinrich Bode, Georg (Celle 1834; rpt. Hildesheim 1968) 209. On Albericus' poetic significance, see Jean Seznec, The Survival of the Pagan Gods (New York 1953) 170–79.Google Scholar

30 'At si Phoebus adest et frenis grypha iugalem / Riphaeo tripodas repetens detorsit ab axe, / Tunc silvae, tunc antra loqui' (lines 30–32). Claudii Claudiani carmina, ed. Birt, Theodor (MGH Auct. ant. 10; Berlin 1892).Google Scholar

31 Apollinaris Sidonii epistulae et carmina 8.9 .7–11, ed. Luetjohann, G. (MGH Auct. ant. 8; Berlin 1887) 136: ‘Ac si Delphica Delio tulissem / instrumenta tuo novusque Apollo / cortinam tripodas, chelyn pharetras, / arcus grypas agam duplaeque frondis / hinc bacas quatiam vel hinc corymbos?’ Cf. Carm. II 307–9: 'Nunc ades, o Paean, lauro cui grypas obuncos / docta lupata ligant, quotiens per fronda lora / flectis penniferos ederis bicoloribus armos'; and Carm. XXII 67: 'grypas et ipse [Apollo] tenet: vultus his laurea curvos / fronde lupata ligant; hederis quoque circumplexis / pendula lora virent; sensim fera subvolat ales / aerias terraeque vias, ne forte citato / alarum strepita lignosas frangat habenas.’ Geoffrey of Vinsauf quotes Sidonius Apollinaris in his Poetria nova to illustrate various rhetorical devices (1796, 1825, 1831). The text is edited by E. Faral, Les arts poétiques du XIIe et du XIIIe siècle (Paris 1924; repr. 1962).Google Scholar

32 'Sine klawen' 298–99. Google Scholar

33 Herodotus, , 3.116 and 4.13.16.Google Scholar

34 Pliny, , Natural History 7.10 (Cambridge, Mass. 1942) II 512. Cf. Aelian, On the Characteristics of Animals (Cambridge, Mass. 1958) 4.27; Pomponius Mela, Chorographia, ed. Frick, Carl (Leipzig 1880) II 1.1; Solinus, Collectanea rerum memorabilium, ed. Mommsen, Theodor (Berlin 1885) 15.22.Google Scholar

36 Isidore, , Etymologiae 14.3.32; Marbod, Liber de gemmis, PL 171.1745; Liber floridus, fol. 229 r; Albertus Magnus, De mineralibus 2.2, ed. Borgnet, A. (Paris 1891) 5.46; Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum naturale 16.90; Jakob von Maerlant, Naturen Bloeme 1749–60; Konrad von Megenburg, Das Buch der Natur 459.Google Scholar

36 De nat. rer. 5.52.Google Scholar

37 For example: Lucidarius, ed. Heidlauf, Felix (Deutsche Texte des Mittelalters 28; Berlin 1915) 10; Rudolph von Ems, Weltchronik, ed. Ehrismann, Gustav (DTM 20; Berlin 1915) 1466–70; Heinrich von Neustadt, Apollonius 10934–48; Die Apocalypse Heinrichs von Hesler, ed. Helm, Karl (DTM 8; Berlin 1907) 21645–54; Himmlische Jerusalem in Die kleinen Denkmäler der Vorauer Handschrift, U. Pretzel and Erich Henschel (Tübingen 1963).Google Scholar

38 Griffons appear with speaking parts ‘Am oberen Peneios,’ where their grasping after gold and their sharp claws are mentioned; in the second scene 'Am oberen Peneios’ they cry: ‘Herein! Herein! Nur Gold zu Häuf! / Wir legen unsre Klauen drauf; / Sind Riegel von der besten Art, / Der grösste Schatz ist wohlverwahrt’ (ed. E. Trunz; Hamburg 1960) 7602–5. I would like to thank Dr. Arnd Bohm of Haverford College for bringing this scene to my attention. Cf. Milton, Paradise Lost 2.943–47. Google Scholar

39 Posed as a tentative question by Johnson, ‘Sine klawen’ 332; 'The wahtær as knight, as singer or poet, or even as Wolfram or his poetic persona?' Google Scholar

40 Parzival 282.20.Google Scholar

41 On the threat posed by the animal, see Wolf, Variation 126, who disagrees that the text conveys any sense of menace and instead speaks of ‘dieses sieghaft aufsteigende Tier’ (133). Google Scholar

42 Wolf, , Variation 125–28, argues that since Tageshass is not characteristic of the watchman within the courtly alba tradition, Wolfram may have modeled the opening of the poem on Christian dawn hymns in which the ‘spiritual watchman’ announces the victory of day over night.Google Scholar

43 Johnson, , ‘Sine klawen’ 312–36; Wolf, Variation 120–21 and 173 n. 77.Google Scholar

44 Wolfgang Haubrichs, 'Deutsche Lyrik,’ in Europäisches Mittelalter, ed. Kraus, Hennig (Wiesbaden 1981) 83–84.Google Scholar

45 On the range of meanings for maere, see Benecke-Müller-Zarncke, Mittelhochdeutsches Wörterbuch (Leipzig 1863) II 1.71–78, and Matthias Lexer, Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuch (Leipzig 1872) I 2045–46. Google Scholar

46 Cf. Johnson's discussion of this retardatio, ‘Sine klawen’ 299–305. Google Scholar

47 On the 'szenischer Natureingang,’ see Barbara von Wulffen, Der Natureingang in Minnesang und frühem Volkslied (Munich 1963) 27–37. CrossRefGoogle Scholar

48 Cf. Sayce 39–43. For an exemplary analysis of Walther's use of the Natureingang, see Arthur Groos, “Shall I Compare Thee to a Morn in May?”: Walther von der Vogelweide and his Lady,’ Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 91 (1976) 398–405. CrossRefGoogle Scholar

49 Cf. Sayce 210–11, and Wolf 119. Google Scholar

50 As suggested in the readings of Wapnewski, Lyrik 107–10, and Jonathan Saville, Erotic Alba 147: 'The watchman is a representative of the social order, who, in his changed loyalty, affirms that the love relationship is superior to the whole social order.’ Google Scholar