Genetic/genomic testing is becoming more widely available within clinical genetic and mainstream medical services. Depending on whether the test is a diagnostic, screening, presymptomatic or predictive test, a range of potential consequences should be considered prior to testing.

This Position Statement presents the major practical, psychosocial and ethical considerations associated with presymptomatic and predictive genetic testing in adults who have the capacity to make a decision (noting that the definition of adult can be different in each jurisdiction), children and young people who lack capacity, and adults living with reduced or fluctuating cognitive capacity. The terms ‘presymptomatic testing’ and ‘predictive testing’ are often used interchangeably. This Statement will use the term ‘predictive testing’ (defined in Table 1) to encompass both presymptomatic and predictive testing.

Table 1. Definitions of terms

This Statement also provides guidelines for health professionals who work with individuals and families seeking predictive genetic testing and laboratory staff conducting the tests.

This position statement replaces 2020PS01 Predictive and Presymptomatic Genetic Testing in Adults and Children.

Figure 1 presents a flow chart summarizing the differences between diagnostic and predictive testing, and the associated considerations.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the differences between diagnostic and predictive testing and associated considerations.

This Position Statement applies to testing for autosomal dominant and X-linked dominant conditions, as well as X-linked recessive conditions, including in individuals with XX chromosomes when the condition may present in a milder form when only one pathogenic variant is present. Predictive testing for mitochondrial conditions is complicated due to variable penetrance and expressivity in children of mothers with a mitochondrial disorder and as such, predictive genetic testing for mitochondrial disorders is not within the scope of this position statement. The guidance applies to the clinical setting, by commercial providers (either clinically mediated or ‘direct to consumer’Footnote 1 ), or under a research protocol. It does not apply to community or population screening for genetic conditions, carrier screening and/or testing, or identification of incidental or unsolicited findings in the course of diagnostic testing.

Predictive testing is often requested when the genetic condition in question has been identified in an affected family member. Testing is only possible when the specific pathogenic variant causing the condition in the affected family member has been identified.

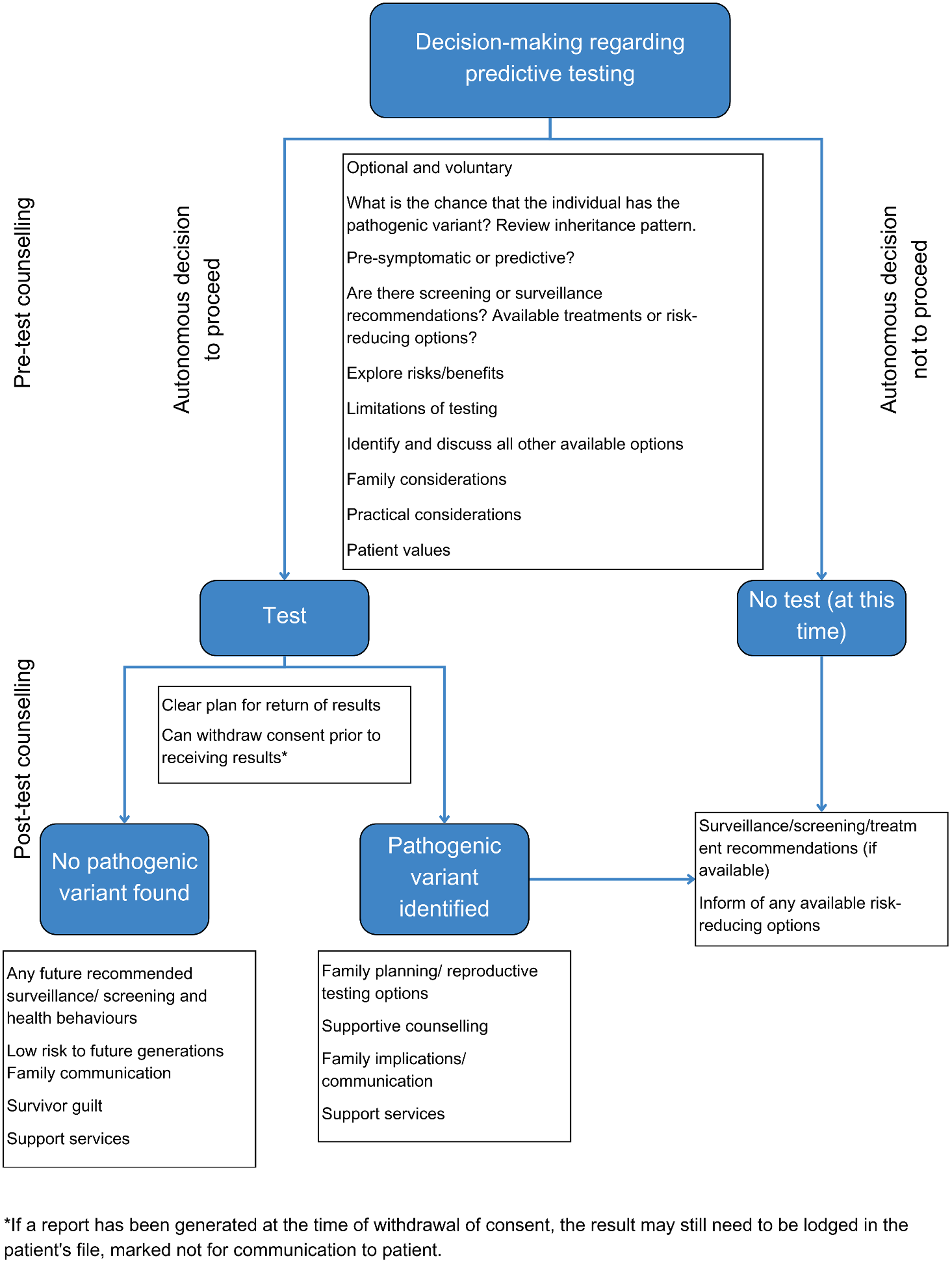

Figure 2 presents a flow chart summarizing the decision-making pathway for predictive testing.

Figure 2. Flow chart of the decision-making pathway for predictive testing.

General Considerations in Predictive Testing

There are a number of considerations when offering predictive testing:

Is there a known genetic diagnosis of the condition in the family?

What is the predictive value of the relevant variant? Does it confer an increased risk (i.e., a predisposition), and if so, what is the degree of risk? Or, does it confer a prediction of future health status?

What is known about the likely age of developing the condition, the natural history of the condition, and the likely symptoms?

Are surveillance options, preventative treatments, or symptom-based treatments available? If so, at what age should they commence? Would they change in the presence of either a positive or a negative result?

Are there any psychosocial benefits or harms associated with understanding personal risk of developing the particular condition? Could this information also be of value to other family members?

How Should the Test Be Provided?

Predictive testing is available when the specific pathogenic variant causing the genetic condition has been identified in an affected family member.

Predictive testing should only be offered with pretest genetic counseling (see Table 1 for definition), and the option or availability of post-test result genetic counseling. The individual may want to bring an appropriate support person, such as a family member or friend, to the appointment. Genetic counseling assists the individual and family to make informed decisions that align with their perceived interests and personal values, based on an understanding of the range of alternative options, the testing process, and the possible implications of predictive genetic testing.

In most circumstances, genetic counseling for predictive testing is provided by genetic counselors. Most genetic counselors work in association with multidisciplinary teams, which may include clinical geneticists, laboratory scientists and medical specialists from a range of other disciplines including oncology, cardiology, neurology and pediatrics. All professionals offering pretest genetic counseling for predictive testing must be knowledgeable about the genetic condition for which testing is being considered, the possible issues associated with accuracy and interpretation of the laboratory test and result, and any relevant psychosocial considerations.

Molecular testing should have a program of quality control and audit similar to the standards recommended by the National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council Standards (2022). Laboratories performing predictive tests should develop protocols, in consultation with those delivering the clinical service, governing the conditions under which samples will be accepted for testing. This may include defining the circumstances in which two samples are to be provided for predictive testing to serve as an internal quality control, and the preference to use a positive familial control.

In most circumstances, predictive genetic testing should not be offered for variants of uncertain significance (VUS). VUS should not be used in clinical decision making to inform the risk to relatives of developing a genetic condition (Richards et al., Reference Richards, Aziz, Bale, Bick, Das, Gastier-Foster, Grody, Hegde, Lyon, Spector, Voelkerding and Rehm2015). Testing of other family members may be requested when a VUS is identified to inform pathogenicity of that variant, also known as segregation analysis.

Pretest Genetic Counseling

Predictive genetic testing should not be performed without the knowledge and participation of the individual providing consent (or their parent/guardian) in the counseling process. When considering whether to continue with a predictive test for a known familial pathogenic variant, every effort should be made to assist the individual or their parent/guardian to make an autonomous and informed decision. This involves considering their capacity to make the best decision for themselves (or their child) based on their perceived interests and personal values. It is imperative that the individual considering testing is aware that predictive testing is voluntary, and that a decision to proceed should be made without coercion or undue influence, in a timeframe that suits them.

An individual’s reasons for seeking testing and their expectations of the test should be explored. Even if the individual seems to have already made a decision to proceed with testing prior to the pretest counseling session, it is important that there is an opportunity to engage with the decision being made. Appropriate information, counseling and support are needed, both pre- and post-test. Interpreters should be used as required.

This information should include (but is not limited to) the following points:

-

1. Risks and benefits of proceeding (or not) with testing, including the potential emotional impact on the individual and other family members and the potential impact on family relationships.

-

2. Possible outcomes of the test (typically whether a pathogenic variant is identified, or no pathogenic variant is found) and the potential implications of those outcomes.

-

3. All available alternatives to predictive testing; for example, if an individual does not proceed with predictive testing, are screening or preventative measures available?

-

4. The inheritance pattern, and possible implications for other family members. For example, testing an individual at 25% risk for a dominant disorder may reveal that an asymptomatic parent has the pathogenic variant and will develop the disease. Although this fact should not override an individual’s access to testing, it should be considered and discussed in counseling before testing. Where appropriate, efforts should be made to involve other at-risk relative(s) in counseling.

-

5. Possible reproductive testing options (e.g., prenatal diagnosis or preimplantation genetic testing [PGT]), or reproductive assistance (e.g., use of donor gametes or adoption).

-

6. Practical information, such as sample requirements, out-of-pocket costs (if applicable), test limitations, that only the familial pathogenic variant will be tested, expected turn-around-time, and that, in some instances, testing may reveal nonpaternity/nonmaternity.

-

7. For some conditions, pretest physical and psychological assessment is recommended (e.g., Huntington disease) and referral to an external specialist may be appropriate.

-

8. A positive test result may adversely affect the ability to obtain or upgrade individually risk-rated insurance policies (such as life or income protection insurance). Once tested, applicants for insurance have a duty to disclose their genetic test result when applying for a new or upgraded insurance policy.Footnote 2

-

9. The possibility of withdrawal from the testing process at any time, including after the test, has been performed but prior to receiving results.

-

10. That the same procedure for return of results will be followed, regardless of the nature of the result.

In some cases, the testing process may require more than one appointment. For some conditions, the process of obtaining consent and sample collection may take place at separate appointments. If the ‘at-risk’ individual or their partner is pregnant and they are considering prenatal testing, the consent and sample collection may be processes that can be done at the same appointment.

Occasionally, to facilitate testing in an individual, additional blood or saliva samples, clinical examination or access to medical and/or genetic records of other family members may be required. In general, the individual requesting testing would approach the relevant family members who need to be involved in the testing process. This should be undertaken with sensitivity, recognising that some family members may not wish to have genetic testing or to even discuss the condition in the family. In addition, some family structures or cultures might require further consultation and wider consent prior to testing.

Confidentiality

The individual considering predictive testing should be informed about how their personal information is stored and accessed. Every effort should be made by the service offering predictive testing to maintain the individual’s privacy and confidentiality. Any documentation related to the individual’s decision-making process and/or the outcome of predictive testing (i.e., test results and relevant correspondence) should be stored appropriately and only accessed with the consent of the individual or as required by law. For more information on confidentiality please see the HGSA’s Position Statement on Use of Human Genetic and Genomic Information in Healthcare Settings (2021PS01, https://hgsa.org.au/Web/Web/Consumer-resources/Policies-Position-Statements.aspx).

Other Important Points to Consider Before Testing Commences

There are specific genetic counseling guidelines for certain adult-onset conditions for which there are no available treatments (e.g., Huntington disease). For certain populations (e.g., Ashkenazi Jewish) testing for a single, known familial variant is not recommended. Broader testing to include all known pathogenic, founder variants or sequencing of the gene should be offered when individuals of certain ethnicities are seeking predictive testing.

Special care should be taken if a predictive test is requested by someone who appears to be affected by the condition for which testing is sought. This may reflect the psychological defense mechanisms of the individual (e.g., denial), which can be important for maintaining wellbeing and social functioning. A clinical opinion may be the next appropriate step after counseling or discussion, rather than predictive testing. If appropriate, diagnostic testing can follow clinical assessment to confirm a diagnosis. In some cases, if the health professional thinks the individual may react adversely to a diagnosis at that time, it may be appropriate to suggest deferring predictive testing, even if the diagnosis is not confirmed. Alternatively, predictive testing may proceed, noting that it will confirm a diagnosis in the patient. There are some advantages in taking this approach for patients who are unaware of their symptoms, including the ability to receive genetic counseling about the condition, and an opportunity to consider how they will incorporate a positive result into their lives. Provided the individual requesting predictive testing accepts that the test may confirm that their current symptoms are associated with the family condition, predictive testing may still be offered.

In all situations, regardless of symptomatic status, a plan for result disclosure should be arranged at the time informed consent for testing is obtained.

Post-test Genetic Counseling

The need for post-test counseling should be discussed with the participant prior to testing, bearing in mind that post-test counseling may be equally important whether or not a pathogenic variant is identified. This should include discussion about an appropriate support person (family or friend) to bring to the appointment and a possible support network (family, friends, minister of religion, community groups, health or welfare professionals) that may be available if required once the result is known.

If at all possible, the results should be disclosed in-person or via telehealth if required, by the individual who provided pretest counseling (or one of the members of the team providing testing). Some individuals may ask for their result to be given by someone outside the testing team (e.g., the family doctor or another health professional). This should be agreed to, if appropriate, provided that the usual post-test information, support, counseling and follow-up is provided by that health professional, or jointly with the team.

Referral for further assistance from another health professional (e.g., psychiatrist, family therapist, social worker or psychologist) or support organisation may be appropriate for some people, either prior to testing and/or in the posttest period. The timeline for follow-up, which should be agreed upon prior to testing, should be reviewed at the result appointment, and arrangements made for the first follow-up contact by the appropriate health professional, if required.

If the positive result is identified, a letter can be provided to the proband to distribute to family members who are at risk of having inherited the genetic condition. This family letter can be drafted without identifying the proband and should contain instructions detailing how to contact an appropriate genetics service to discuss their personal risk.

Additional Considerations for Children and Young People

Assessing Capacity to Make Medical and Health Decisions

Young people can be ‘immature’ (i.e., do not have the cognitive capacity and psychosocial maturity to make the decision to have a predictive test), or ‘mature’ (i.e., have such a capacity). Regarding the latter:

In South Australia, specific legislation exists to allow young people aged 16 and over to be treated as adults for the purposes of consenting to medical treatment.

In all other states and territories of Australia, any young person under the age of 18 may be deemed to have capacity to make a decision for themselves if they have ‘sufficient understanding and intelligence’ to enable a full understanding of the particular medical intervention being proposed. This type of capacity has been termed ‘Gillick’ competence.Footnote 3 The Gillick competence rule provides a legal tool for assessing whether the child is competent to make their own health decisions.

In New Zealand, the consent (or refusal to consent) to medical procedures by young people aged 16 and over has effect as if the young person were of full age (Care of Children Act 2004 s 36). Below that age, parental consent may not always be necessary, and a child may consent to medical procedures if they are sufficiently mature to make the decision (Medical Council of New Zealand, 2021).

For people aged under 18 who do not have legal capacity, usually the person(s) with legal responsibility for them will make the decision on their behalf. This decision should be one that is made in the best interests of the child, although it is noted that what constitutes ‘best interests’ is the subject of ongoing ethical debate. Psychological assessment may be required to determine an individual’s cognitive and psychosocial maturity and their ability to understand genetic concepts and make an informed decision. Individuals need to appreciate that the decisions they make might have long-term consequences for psychological health, social circumstances, relationships, employment and ability to obtain certain insurance products. However, even young people without the capacity to make a decision can, and should, be included in the decision-making process. The appropriate level of inclusion in the decision will depend on their age, experiences, and level of maturity.

In the event of a dispute between the young person and their parents regarding predictive genetic testing, the health professional should act as an advocate for the young person. However, resolution of such a dispute should recognise that the young person is part of a family, with counseling focusing on the family and young person together, and separately.

Circumstances in Which Testing May Be Appropriate in Children or Young People

There are a range of contexts in which predictive testing in children might be considered. Whether testing is appropriate depends on a range of factors, such as the age at which symptoms of the condition are likely to start and whether treatment, surveillance or preventative measures can be taken in response to the knowledge of genetic status. For simplicity, these contexts can be broken down into the following broad categories:

Category 1: Childhood onset, actionable (e.g., familial adenomatous polyposis)

Category 2: Childhood onset, nonmedically actionable (e.g., retinitis pigmentosa)

Category 3: Adult onset, actionable (e.g., hereditary breast and ovarian cancer)

Category 4: Adult onset, nonmedically actionable (e.g., Huntington disease).

Systematic reviews of the literature have shown a lack of research studies on the psychosocial impact of predictive testing in children and young people. Findings from the research that does exist suggest testing has most commonly been undertaken for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary cardiac disease risk (Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield, Hanlon, Tucker, Patenaude, Signorelli, McLoone and Cohn2016). While several studies showed nonsignificant increases in depression scores following testing, the majority concluded that short-term adverse psychological outcomes of predictive testing, such as anxiety and depression after testing, were infrequent. There is, however, some evidence to suggest that children with a parent affected by the condition, and those who test positive, may be more at risk of adverse outcomes (Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield, Hanlon, Tucker, Patenaude, Signorelli, McLoone and Cohn2016).

There may be situations where it is considered appropriate for a child or young person to undergo such predictive testing, even when the young person is not able to fully engage with the testing process. In such rare circumstances, a decision may be reached between the health professionals and the family that it is appropriate to perform testing in the young person because it is the best option to support the wellbeing of the child or young person through constructive family dynamics. When such requests arise, they should be discussed with other members of the genetics service or, where available, a clinical ethics committee. For clarity, this section of the Position Statement should not be taken as HGSA endorsement of routine predictive testing for adult-onset conditions in young people who cannot consent.

Counseling should be provided using language that can be best understood by the child or young person and their parents/guardians. The child or young person should be given the option to be seen alone for at least part of each genetic counseling session. Follow-up counseling should be available from appropriate professionals. Parents/guardians should be encouraged to prioritize the outcome of predictive testing in terms of the benefit to the individual rather than in terms of the benefit to others.

Whether or not predictive testing takes place, parents/guardians should be encouraged to foster an awareness in the child or young person of the genetic condition in the family and its implications. This enables the child or young person to be raised with this knowledge. Being able to discuss this information within the family, at different stages of maturity, will ultimately enable the child or young person to have a better understanding of the outcome of testing (if performed in childhood), or to make a more informed choice about predictive genetic testing once they are older.

Adults With Reduced Capacity to Give Informed Consent

People with a reduced cognitive capacity, such as adults living with intellectual disability, require special consideration. Regardless of the individual’s capacity to provide informed consent, information needs to be provided in a manner appropriate to their cognitive ability, and efforts should be made to sensitively explore their understanding. If the individual does not have capacity, they should still be actively included in the counseling process along with the person who has authority to make decisions on their behalf (e.g., guardian or power of attorney). A support person (carer, legal guardian, family member) should be present if possible and appropriate. Reasons for being offered the test should be explored to ensure that the individual with reduced capacity understands and is not being coerced or unduly influenced into undergoing testing. Testing may be offered to help plan medical and care needs of the individual being offered testing. There may also be situations where it is appropriate that testing is offered to benefit other family members. When this occurs, the decision should prioritize the wellbeing and interests of the individual being tested.

Acknowledgments

We thank the working group for this position statement: Danya Vears, Alison McLean, Chloe La Spina, and Aideen McInerney-Leo. We also acknowledge the additional members of the Education, Ethics, and Social Issues Committee of the Human Genetics Society of Australasia, both current and past, who contributed to this statement: Julia Mansour, Sam Ayers, Amy Nisselle, Jackie Boyle, Ainsley Newson, Heather Renton, Dylan Mourdant, Gabrielle Reid, Rebekah McWhirter, Fiona Lynch, Alison McIvor, Russel Gear and Elisha Swainson. This statement was reviewed and approved by the HGSA Council in November 2023.

Financial support

A.M.L. is currently supported by a University of Queensland Faculty of Medicine Fellowship.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical Standards

Not applicable