Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 July 2011

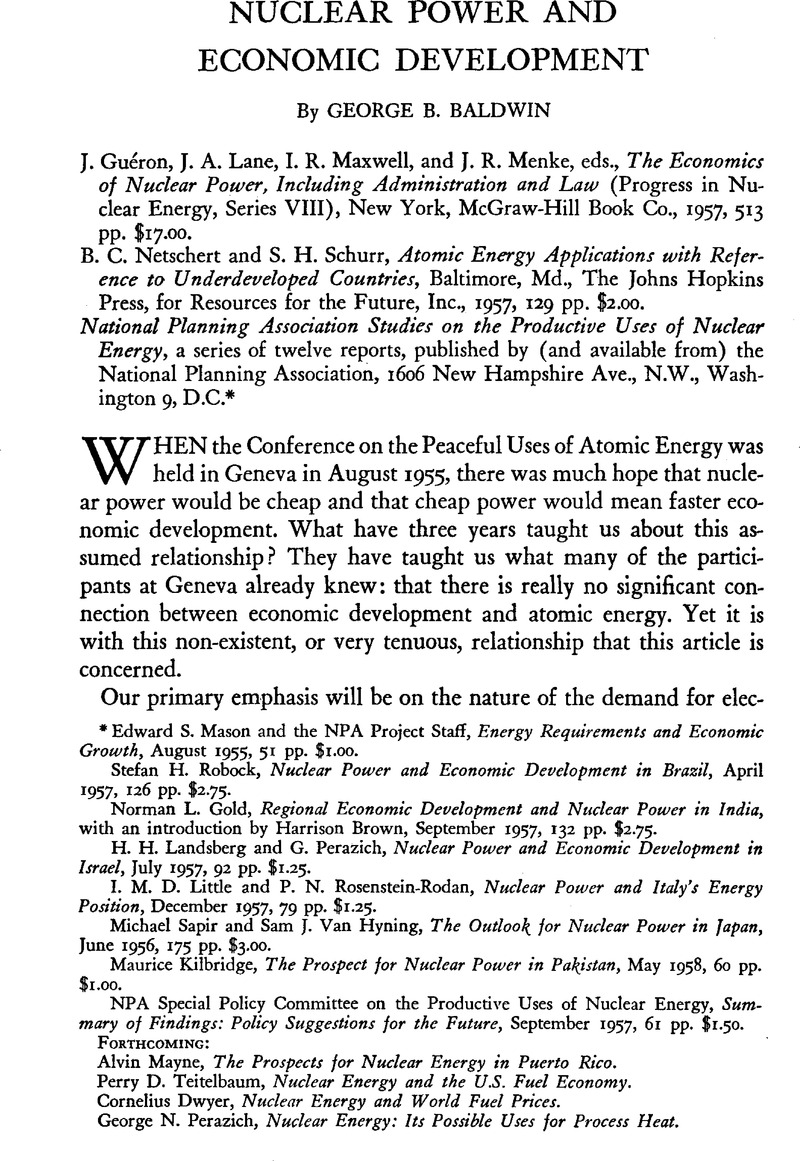

* Edward S. Mason and the NPA Project Staff, Energy Requirements and Economic Growth, August 1955, 51 pp. $1.00.

Robock, Stefan H., Nuclear Power and Economic Development in Brazil, April 1957, 126 pp. $2.75.Google Scholar

Gold, Norman L., Regional Economic Development and Nuclear Power in India, with an introduction by Harrison Brown, September 1957, 132 pp. $2.75.Google Scholar

Landsberg, H. H. and Perazich, G., Nuclear Power and Economic Development in Israel, July 1957, 92 pp. $1.25.Google Scholar

Little, I. M. D. and Rosenstein-Rodan, P. N., Nuclear Power and Italy's Energy Position, December 1957, 79 pp. $1.25.Google Scholar

Sapir, Michael and Van Hyning, Sam J., The Outlook for Nuclear Power in Japan, June 1956, 175 pp. $3.00.Google Scholar

Kilbridge, Maurice, The Prospect for Nuclear Power in Pakistan, May 1958, 60 pp. $1.00.Google Scholar

NPA Special Policy Committee on the Productive Uses of Nuclear Energy, Summary of Findings: Policy Suggestions for the Future, September 1957, 61 pp. $1.50.

FORTHCOMING:

Alvin Mayne, The Prospects for Nuclear Energy in Puerto Rico.

Perry D. Teitelbaum, Nuclear Energy and the U.S. Fuel Economy.

Cornelius Dwyer, Nuclear Energy and World Fuel Prices.

George N. Perazich, Nuclear Energy: Its Possible Uses for Process Heat.

1 The prevalence of power shortages in underdeveloped countries is a misleading index of the degree of such countries' true need for additional power. Once supply has been brought even with demand—a heroic task in many countries—demand will expand only slowly (unless industrialization is proceeding rapidly, as in Brazil or Mexico). Also, high percentage rates of electricity growth often reflect the present smallness of the industry rather than the addition of large amounts of new capacity expressed in absolute terms.

2 See the crisp review by Harold J. Barnett in the American Economic Review, XLVII, No. 5 (September 1957), pp. 760–61. Barnett calls the United Nations' Volume I “an economic analysis performance significantly superior to the McGraw-Hill volume.”

3 In high-income countries, the consumption of electricity becomes much more sensitive to its price, since a low price can persuade people to invest in new appliances for the first time or to shift from other forms of energy to electricity. Sophomore economics teaches us that the shape of any demand curve depends, among other things, on how much income people have: it is true!

4 The importance of operating “know-how” was publicly demonstrated when the Argonne National Laboratory in Chicago announced in December 1957 that it had achieved a 40 per cent reduction in the cost of power from its small reactor. This resulted from a relatively simple adjustment in the operating positions of the fuel rod elements. (See the report in the New York Times, December 31, 1957.) In April 1958 the Laboratory announced a further increase in efficiency, so that the reactor could in effect be made to yield three times more electricity than its designers had predicted, implying a great reduction in unit costs. (New York Times, April 5, 1958.)